Abstract

Understanding the molecular principles governing interactions between transcription factors (TFs) and DNA targets is one of the main subjects for transcriptional regulation. Recently, emerging evidence demonstrated that some TFs could bind to DNA motifs containing highly methylated CpGs both in vitro and in vivo. Identification of such TFs and elucidation of their physiological roles now become an important stepping-stone toward understanding the mechanisms underlying the methylation-mediated biological processes, which have crucial implications for human disease and disease development. Hence, we constructed a database, named as MeDReaders, to collect information about methylated DNA binding activities. A total of 731 TFs, which could bind to methylated DNA sequences, were manually curated in human and mouse studies reported in the literature. In silico approaches were applied to predict methylated and unmethylated motifs of 292 TFs by integrating whole genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) and ChIP-Seq datasets in six human cell lines and one mouse cell line extracted from ENCODE and GEO database. MeDReaders database will provide a comprehensive resource for further studies and aid related experiment designs. The database implemented unified access for users to most TFs involved in such methylation-associated binding actives. The website is available at http://medreader.org/.

INTRODUCTION

In the process of gene transcription cooperative interactions between transcription factors (TFs) and DNA methylation play an important role in regulating gene expression. The classical view of TF–DNA interaction is that TFs usually bind to non-methylated DNA motifs in open chromatin regions, whereas high level of methylation at CpG dinucleotides (mCpG) in the cis-regulatory elements prohibits recruitment of TFs, except only a few proteins with a mCpG-binding domain (MBD), including MeCP2, MBD1, MBD2 and MBD4. These MBD proteins are known to recognize methylated DNA in a sequence-independent manner (1,2). However, several TFs without MBDs were found to interact with methylated DNA in sporadic studies previously. For example, transcription factor KLF4 (3), Kaiso (4), ZFP57 (5) and CEBPα (6) were identified with high affinity to distinct methylated DNA sequences. More recently, systematic efforts have revealed that hundreds of TFs could specifically bind to methylated DNA by means of tandem mass spectrometry (7), functional protein microarray (3), DNA microarray (8), systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX) (9) and ChIP-BS-seq (10). Identification of such TFs and elucidation of their functions become important stepping stones towards understanding the mechanism underlying these methylation-mediated biological processes, leading to crucial implications for human diseases and cancer.

Over the past 30 years, many databases have been constructed to archive information of TF binding sites, providing invaluable resources for the transcription community and beyond. For instance, TRANSFAC (11), JASPAR (12) and UniPROBE (13) are the most common open-access databases containing hundreds of transcription factor position weight matrices (PWMs) constructed from DNA binding sequences. The PWMs can help search and predict potential TF binding sites in the whole genome. Meanwhile, TF regulatory activity has been known as biological species-dependent. Hence, lots of species-specific TF databases were created, such as PlantTFDB for plant (14), AnimalTFDB for Animal (15) and ITFP for human, mouse and rat (16). Some databases such as TFBSshape (17) not only contain extensive nucleotide sequences of TFs, but also calculate DNA structural features from nucleotide sequences provided by motif databases. Unfortunately, none of these databases records methylated DNA binding sites for TFs.

With the advance of next generation sequencing technologies, DNA methylation sites can be determined at the single base pair resolution. A number of systematical DNA methylation databases have been developed for epigenetic studies. As the first DNA methylation database, MethDB stores DNA methylation data and gene expression information (18). NGSMethDB archives DNA methylation profiles generated from bisulfite sequencing technique (19). MethBank (20), MethyCancer (21) and MENT (22) focus on DNA methylation status of some specific biological problems, such as embryonic development and multifarious cancers. MethSMRT hosts the DNA N6-methyladenine and N4-methylcytosine methylomes (23). ENCODE database also contains many datasets of Whole Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) and ChIP-Seq datasets obtained from many cell lines. These databases provide us with a large amount of profiles including TFs binding sequences and corresponding DNA methylation status. However, none of the existing databases systematically documents the interactions between TFs and methylated DNA sequences.

To fill this gap for the researchers to better understand the interactions between DNA methylation and TFs, we collected information about methylated DNA–TF interactions from two major public sources: published literatures and ENCODE database. We developed a database, dubbed as MeDReaders, where 753 methylated DNA–TF interactions involving 731 TFs were manually curated from the literature. A total of 292 TFs were predicted to bind to distinct methylated and unmethylated DNA motifs based on integration of WGBS data and ChIP-Seq data in six human cell lines and one mouse cell line extracted from ENCODE and GEO database. MeDReaders can help the scientists to compare methylated DNA binding activities between different species and datasets, and further understand the biological processes that are mediated by DNA methylation. The MeDReaders is publicly available at http://medreader.org/ without use restriction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data sources

To extract experimentally confirmed methylated DNA–TF interactions from the published literatures, we first searched all relevant papers from the PubMed literature database. CEBPα (3,6), ZFP57/KAP1 (5,24), ZBTB33 (4), CEBPB/ATF4 (25) were found to interact with methylated DNA using EMSA or ChIP-BS-seq experiments. Hundreds of TFs were identified to prefer CpG-methylated sequences by high-throughput technology, such as Tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) (26,27), protein microarray (3), methylation-sensitive SELEX (9). In total we manually curated 753 methylated DNA–TF interactions involving 731 TFs from 4 human cell lines/tissues and 4 mouse cell lines/tissues (Table 1). However, the retrieved records are different due to diverse methods in individual experiments. For example, using SELEX in vitro, we only got TF binding motifs instead of binding sequences. But we obtained some protein binding DNA sequences from protein arrays, where methylated binding motif logos for only a few specific TFs can be retrieved.

Table 1. Transcription factors summarized from published literatures.

| Species | No. of TFs | No. of cells/tissues |

|---|---|---|

| Human | 601 | 4 |

| Mouse | 130 | 4 |

Another way to access the interaction between TFs and methylated DNA sequences is to re-analyze the datasets from the ENCODE Consortium and NCBI GEO by focusing on the methylation levels of TF binding regions. We downloaded WGBS data for four human cell lines, ChIP-Seq data for six human and one mouse cell lines from the ENCODE, and WGBS data of ES-E14, IMR-90 and HCT116 cell lines and ChIP-Seq of ES-E14 cell from the GEO with accession numbers GSM1027571, GSM2210597, GSM1465024 and GSM699165 (Table 2). All datasets were re-processed using the ENCODE standard pipeline. In summary, Bismark (28) was used for the WGBS data analysis to align sequencing reads then call methylation levels, while the Irreproducible Discovery Rate method (29) was employed for ChIP-Seq data to call the TF binding peaks.

Table 2. Transcription factors inferred by WGBS and ChIP-Seq datasets.

| Species | Cell/tissue | No. of TFs |

|---|---|---|

| Human | GM12878 | 44 |

| Human | H1-hESC | 33 |

| Human | HepG2 | 89 |

| Human | HCT116 | 5 |

| Human | IMR-90 | 6 |

| Human | K562 | 110 |

| Mouse | E14 | 5 |

Sequence motifs containing methylated sites

The same computational method described in our published paper (30) was adopted to predicted methylated and unmethylated motifs of TFs by integrating WGBS and ChIP-Seq data. DNA sequences within each ChIP-Seq peak were extracted and grouped based on their average methylation level. The MEME (31) algorithm was used to predict significantly enriched sequence motifs in each group. The predicted motif was then utilized to scan the ChIP-Seq peak region. We recorded the DNA segment with highest match score to the motif, while examining the methylation level on the CpG within the identified DNA segment. At last, the high and low methylation motifs were reconstructed according to the DNA methylation levels (cutoff 0.6) of CpG sites in the predicted TF binding segment. We introduced a new letter ‘E’ to represent highly methylated-C within TF binding sequences. Many interactions between TFs and methylated DNA were predicted by computational method, which provide the starting point for further in vivo characterization of TF binding patterns and high-resolution DNA methylation analyses.

Database implementation

The website was built using Spring boot framework. The database was organized by H2 database and queried through the Hibernate DAO layer. The web pages were constructed using HTML5 and rendered using Thymeleaf template. Jquery library was used with Semantic UI framework to provide a responsive user friendly front-end interface.

RESULTS

Usage and access

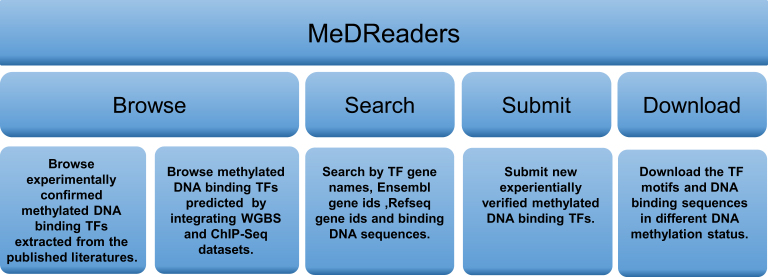

User-friendly web interface was developed to facilitate users to browse, search and download the methylated DNA–TF interactions data, and upload new experiemntially verified methylated DNA–TF interactions to the database. Once reviewed and approved by the managers of the database, the newly submitted data will be included in the database, and made available to the public in the coming release. The main functionality of MeDReaders is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Functionality of MeDReaders.

Browsing the database

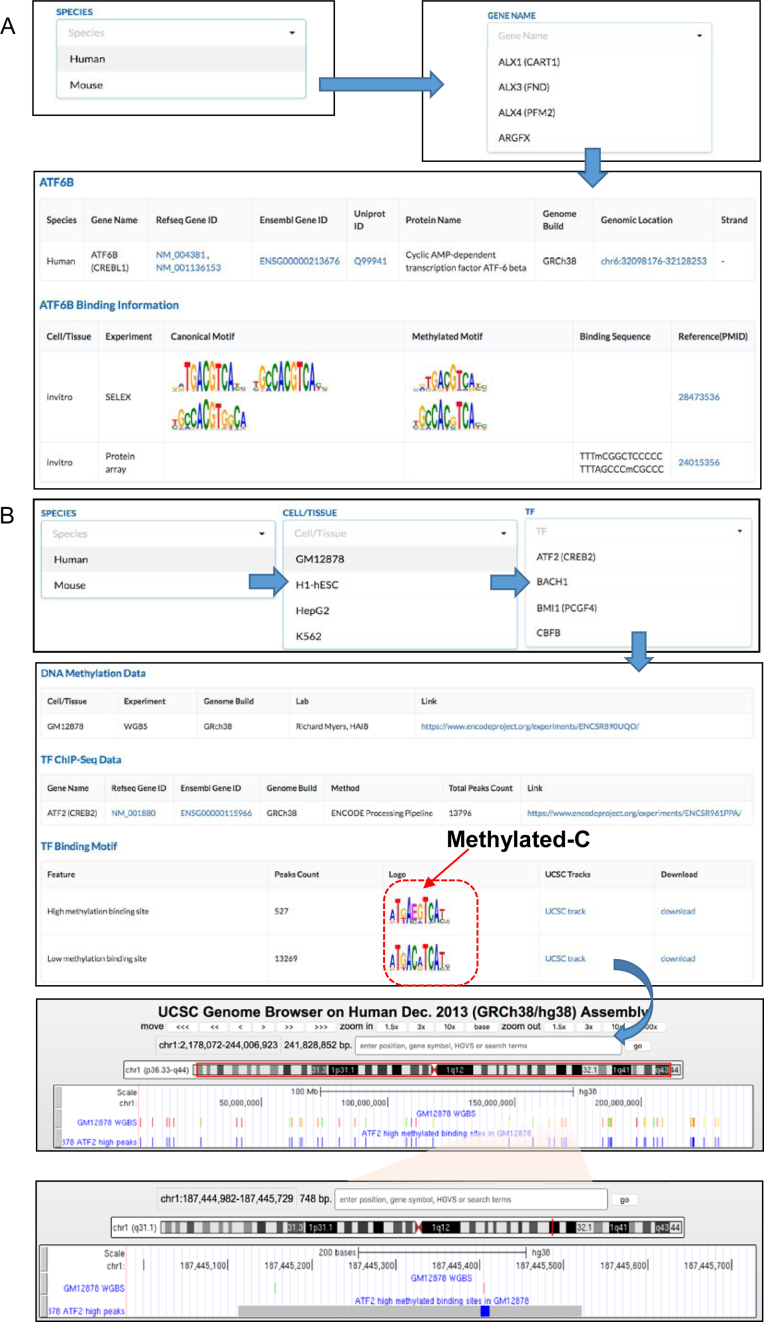

Data in MeDReaders knowledge base can be browsed by TF gene symbols. To browse the methylated DNA binding TFs data from two major sources, users first go into the ‘High-methyl(TFs)’ and ‘Methylome+CHIP-Seq’ pages, respectively. For example, if a user wants to know whether a human TF named ‘ATF6B’ is known to bind to methylated DNA in the literature, s/he can go to the ‘High-methyl(TFs)’ page and then select ‘human’ and ‘ATF6B(CREBL1)’. On this page, the basic information of the selected TF is shown, such as the genomic location, strand and Uniprot ID, Refseq Gene ID, Ensembl Gene ID, to name a few. Dependent on the experimental methods, some DNA motifs are provided with the raw binding sequences, but others not. When a user is interested in the methylated DNA binding TFs predicted with the in silico method via integrating WGBS and ChIP-Seq data, s/he can go to the ‘Methylome+CHIP-Seq’ page and then select a species, cell lines/tissues, and a TF-of-interest. For example, in searching a TF named ‘ATF2(CREB2)’ in human GM12878 cell line, ATF2’s motifs for methylated and unmethylated DNA binding sites will be shown on this page. Two examples on how to browse the database are shown in the Figure 2A and B. We also provide a useful link to visualize TF binding peaks with associated DNA methylation levels underneath by adding custom tacks in UCSC Genome Browser.

Figure 2.

Screenshot of how to browser MeDReaders. (A) Screenshot of browsing the records retrieved from published literatures. (B) Screenshot of browsing the methylated DNA–TF interactions predicted by integrating WGBS and ChIP-Seq data and visualizing the DNA methylation and TF binding sites by using UCSC Genome Browser.

Searching the database

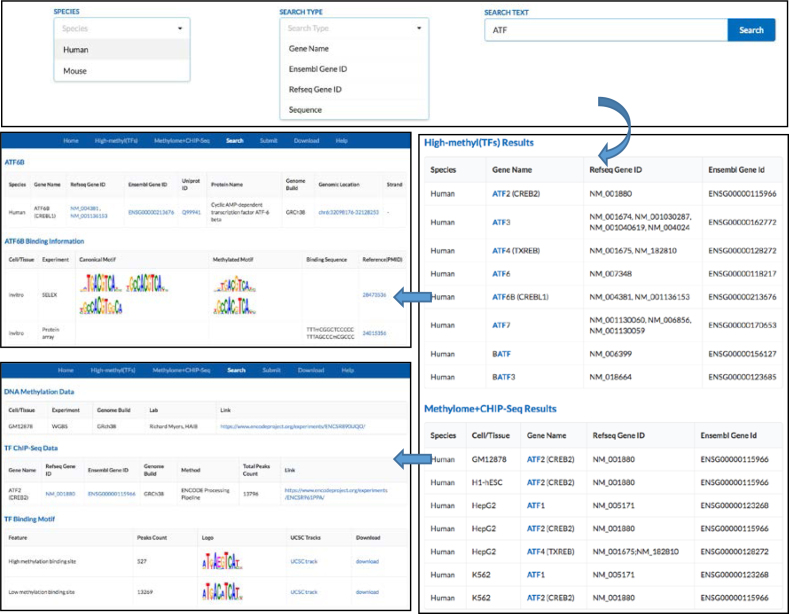

The MeDReaders database provides a ‘Search’ page for users to search methylated DNA–TF interactions by TF names, Ensemble gene IDs, RefSeq gene IDs or binding DNA sequences. Users can obtain the TF basic information and the TF binding DNA motif and sequences. For example, if a user wants to query the ATF TF subfamily, they can select a species and type in ‘ATF’. As a result, all records about those TFs in the ATF subfamily collected from the two resources will be shown. An example on how to retrieve information about the ATF subfamily in humans is shown Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Screenshot of how to search the data.

Submitting and downloading

It is our expectation that more interactions between TF and methylated DNA will be found in future systematic studies. To accommodate this demand, MeDReaders provides a submission page for users to upload new experimentally verified methylated DNA–TF interactions. After manual curation and computational analysis, the new information about methylated DNA binding TFs will be uploaded to our database. MeDReaders also provides a download page for users to download the profiles. Each predicted methylated-DNA binding TF file contained all peaks information and TF binding sites information, including CpG site loci, methylation levels, methylated read number and total read number in WGBS experiment.

DISCUSSION

MeDReaders is the first resource focusing on the interactions between methylated DNA and TFs. With more evidences to demonstrate the importance of methylated DNA binding TF binding activities in physiologically relevant contexts, we foresee that more researchers will be focusing on elucidating the biological consequences of the methylated DNA–TF binding activities in the near future. With the rapid accumulation of WGBS and ChIP-Seq experiments, more methylated DNA–TF interactions would be predicted in multiple model organisms. Researchers can take advantage of such information from this database for further epigenetic-associated TF regulation studies. People also can perform specific validation on targets of their interest based on our summarized predictions. Therefore, we will continue to expand MeDReaders database with the new publicly available datasets and keep improving the algorithms for deep mining. We believe that our database will become a valuable resource for methylated DNA binding TF community.

In our previous study, we observed that many TFs bind to both methylated and unmethylated DNA, but the sequence of the methylated binding sites are often different to their canonical unmethylated sequences (3). These observations suggested that DNA methylation altered the binding specificity. Therefore, we considered these cases as methylation-dependent binding. On the other hand, Taipale and colleagues (9) reported that some TFs could bind to methylated and unmethylated DNA with the same binding sites. In such cases, the TF-DNA interactions are methylation-independent. The MeDReaders is likely to contain two types of interactions. Further experiments are required to distinguish the two situations.

We are fully aware that superimposing the independent ChIP-seq and methylome data cannot prove that the TF binding and methylation events are from the same cells because both measurements are population-based. Ideally, one should perform ChIP followed by bisulfite-sequencing to confirm that a give TF indeed binds to the methylated DNA. In our previous publication, we tested some of methylated sites using this approach (3). However, since this approach does not perform well on a genomic scale, we are not able to find such genome-wide data. Nonetheless, we believe our ‘predicted’ methylated binding sites are valuable to the community because such data provide a starting point for the researchers to further investigate the methylated DNA–TF interactions. Furthermore, we let users set cutoff values for methylation level retrieved from the downloadable file to consider methylated binding sites. For example, if a user sets methylation level of 1.0 to be considered as a high methylation level, the TF ChIP-Seq sites will definitely co-occur with methylated sites in cells.

FUNDING

Natural Science Foundation of China [61371179, 6177011237 to G.W.]; The International Postdoctoral Exchange Fellowship [20130053 to G.W.]; China Postdoctoral Science Foundation Funded Project [2014M551246 to G.W.]; New Century Excellent Talents Support Program from the Ministry of Education [NCET-13-0176 to G.W.]; National Institutes of Health grants [EY024580, GM111514, EY023188, R01EY020560 to J.Q.]. Funding for open access charge: National Natural Science Foundation of China [61371179 to G.W.].

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Jaenisch R., Bird A.. Epigenetic regulation of gene expression: how the genome integrates intrinsic and environmental signals. Nat. Genet. 2003; 33:245–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hendrich B., Tweedie S.. The methyl-CpG binding domain and the evolving role of DNA methylation in animals. TRENDS Genet. 2003; 19:269–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hu S., Wan J., Su Y., Song Q., Zeng Y., Nguyen H.N., Shin J., Cox E., Rho H.S., Woodard C. et al. DNA methylation presents distinct binding sites for human transcription factors. Elife. 2013; 2:e00726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Prokhortchouk A., Hendrich B., Jørgensen H., Ruzov A., Wilm M., Georgiev G., Bird A., Prokhortchouk E.. The p120 catenin partner Kaiso is a DNA methylation-dependent transcriptional repressor. Genes Dev. 2001; 15:1613–1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Quenneville S, Verde G, Corsinotti A, Kapopoulou A., Jakobsson J., Offner S., Baglivo L., Pedone p.V., Grimaldi G., Riccio A. et al. In embryonic stem cells, ZFP57/KAP1 recognize a methylated hexanucleotide to affect chromatin and DNA methylation of imprinting control regions[J]. Mol. Cell. 2011; 44:361–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rishi V., Bhattacharya P., Chatterjee R., Rozenberg J., Zhao J., Glass K., Fitzgerald P., Vinson C.. CpG methylation of half-CRE sequences creates C/EBPα binding sites that activate some tissue-specific genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010; 107:20311–20316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Iurlaro M., Ficz G., Oxley D., Raiber E.A., Bachman M., Booth M.J., Andrews S., Balasubramanian S., Reik W.. A screen for hydroxymethylcytosine and formylcytosine binding proteins suggests functions in transcription and chromatin regulation. Genome Biol. 2013; 14:R119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mann I.K., Chatterjee R., Zhao J., He X., Weirauch M.T., Hughes T.R., Vinson C.. CG methylated microarrays identify a novel methylated sequence bound by the CEBPB| ATF4 heterodimer that is active in vivo. Genome Res. 2013; 23:988–997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yin Y., Morgunova E., Jolma A., Kaasinen E., Sahu B., Khund-Sayeed S., Das P.K., Kivioja T., Dave K., Zhong F. et al. Impact of cytosine methylation on DNA binding specificities of human transcription factors. Science. 2017; 356:eaaj2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brinkman A.B., Gu H., Bartels S.J., Zhang Y., Matarese F., Simmer F., Marks H., Bock C., Gnirke A., Meissner A., Stunnenberg H.G.. Sequential ChIP-bisulfite sequencing enables direct genome-scale investigation of chromatin and DNA methylation cross-talk. Genome Res. 2012; 22:1128–1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wingender E., Chen X., Hehl R., Karas H., Liebich I., Matys V., Meinhardt T., Prüß M., Reuter I., Schacherer F.. TRANSFAC: an integrated system for gene expression regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000; 28:316–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sandelin A., Alkema W., Engström P., Wasserman W.W., Lenhard B.. JASPAR: an open–access database for eukaryotic transcription factor binding profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004; 32:D91–D94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Newburger D.E., Bulyk M.L.. UniPROBE: an online database of protein binding microarray data on protein–DNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008; 37:D77–D82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jin J., Tian F., Yang D.C., Meng Y.Q., Kong L., Luo J., Gao G.. PlantTFDB 4.0: toward a central hub for transcription factors and regulatory interactions in plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017; 45:D1040–D1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang H.M., Chen H., Liu W., Liu H., Gong J., Wang H., Guo A.Y.. AnimalTFDB: a comprehensive animal transcription factor database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011; 40:D144–D149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zheng G., Tu K., Yang Q., Xiong Y., Wei C., Xie L., Zhu Y., Li Y.. ITFP: an integrated platform of mammalian transcription factors. Bioinformatics. 2008; 24:2416–2417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yang L., Zhou T., Dror I., Mathelier A., Wasserman W.W., Gordân R., Rohs R.. TFBSshape: a motif database for DNA shape features of transcription factor binding sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013; 42:D148–D155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Grunau C., Renault E., Rosenthal A., Roizes G.. MethDB—a public database for DNA methylation data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001; 29:270–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hackenberg M., Barturen G., Oliver J.L.. NGSmethDB: a database for next-generation sequencing single-cytosine-resolution DNA methylation data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010; 39:D75–D79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zou D., Sun S., Li R., Liu J., Zhang J., Zhang Z.. MethBank: a database integrating next-generation sequencing single-base-resolution DNA methylation programming data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014; 43:D54–D58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. He X., Chang S., Zhang J., Zhao Q., Xiang H., Kusonmano K., Yang L., Sun Z.S., Yang H., Wang J.. MethyCancer: the database of human DNA methylation and cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007; 36:D836–D841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Baek S.J., Yang S., Kang T.W., Park S.M., Kim Y.S., Kim S.Y.. MENT: methylation and expression database of normal and tumor tissues. Gene. 2013; 518:194–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ye P., Luan Y., Chen K., Liu Y., Xiao C., Xie Z.. MethSMRT: an integrative database for DNA N6-methyladenine and N4-methylcytosine generated by single-molecular real-time sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017; 45:D85–D89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Strogantsev R., Krueger F., Yamazawa K., Shi H., Gould P., Goldman-Roberts M., McEwen K., Sun B., Pedersen R., Ferguson-Smith A.C.. Allele-specific binding of ZFP57 in the epigenetic regulation of imprinted and non-imprinted monoallelic expression. Genome Biol. 2015; 16:112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mann I.K., Chatterjee R., Zhao J., He X., Weirauch M.T., Hughes T.R., Vinson C.. CG methylated microarrays identify a novel methylated sequence bound by the CEBPB| ATF4 heterodimer that is active in vivo. Genome Res. 2013; 23:988–997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Spruijt C.G., Gnerlich F., Smits A.H., Pfaffeneder T., Jansen P.W., Bauer C., Münzel M., Wagner M., Müller M., Khan F. et al. Dynamic readers for 5-(hydroxy) methylcytosine and its oxidized derivatives. Cell. 2013; 152:1146–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bartke T., Vermeulen M., Xhemalce B., Robson S.C., Mann M., Kouzarides T.. Nucleosome-interacting proteins regulated by DNA and histone methylation. Cell. 2010; 143:470–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Krueger F., Andrews S.R.. Bismark: a flexible aligner and methylation caller for Bisulfite-Seq applications. Bioinformatics. 2011; 27:1571–1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li Q., Brown J.B., Huang H., Bickel P.J.. Measuring reproducibility of high-throughput experiments. Ann. Appl. Stat. 2011; 5:1752–1779. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhu H., Wang G., Qian J.. Transcription factors as readers and effectors of DNA methylation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2016; 17:551–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bailey T.L., Boden M., Buske F.A., Frith M., Grant C.E., Clementi L., Ren J., Li W.W., Noble W.S.. MEME SUITE: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009; 37:W202–W208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]