Introduction

Amid the recruitment crisis currently facing nephrology, there is concern among nephrology educators that a proportion of fellows will struggle with clinical performance. In a recent survey of nephrology program leaders conducted by the American Society of Nephrology Workforce and Training Committee, 88% of respondents report remediating at least one fellow over the last 5 years (1). There is growing evidence that a structured approach to evaluating and remediating the underperforming trainee can be effective (2).

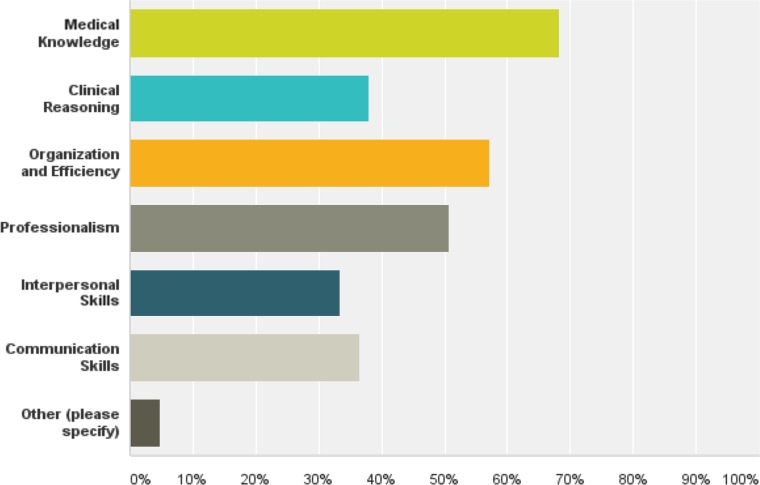

Areas of struggle among graduate learners are commonly categorized according to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) competency schema (3), although we find that these competencies are often too broad to allow for specific diagnosis and treatment. For instance, a patient care deficit may reflect an underlying problem with knowledge, clinical reasoning, or triaging tasks. In the aforementioned survey, we asked program leaders to identify the most common deficits observed among nephrology fellows over the last 5 years (Figure 1). Medical knowledge, as reported among internal medicine residents (3,4), is a common area of struggle followed by organization/efficiency, which is not one of the six ACGME competencies. A deficiency in organization and efficiency can represent many things: true organizational challenges, weakness in clinical reasoning, underlying issues with mental wellbeing, and underpreparedness for a large and complex fellowship. Professionalism is a common area of struggle among nephrology trainees where remediation is complicated and is not always successful (2,3). Additional issues with stress, depression, anxiety, and impairment occur in up to one third of cases and can negatively affect performance (3,4).

Figure 1.

Medical knowledge and organization and efficiency were the most common deficits remediated by nephrology program leaders.

We propose a systematic approach to assessment and coaching of the nephrology fellow struggling with clinical performance. Given that the term remediation carries considerable stigma and often connotes disciplinary action, we advocate use of the term coaching to signify a process by which a struggling trainee receives individualized mentorship and guidance from an individual who is committed to his/her success and is not directly involved in his/her reassessment.

Assessment of the Struggling Fellow

Early recognition of the struggling fellow is critical to allow time for successful coaching or for the minority of trainees that we cannot help, career redirection. Faculty can be helpful in early identification of underperforming fellows but may not feel comfortable discussing concerns directly with the fellow or the Program Director (PD). Potential obstacles include denial, perceived negative consequences to the learner, lack of comfort with or resources for remediation, and fear of retaliation or legal ramification (5). Improved recognition often requires an institutional culture change, in which faculty accept that some trainees will struggle, can and should be identified early, and will benefit from constructive feedback and coaching.

Success in a coaching program hinges on determination of the specific primary deficit and requires a systematic assessment that goes beyond the Clinical Competency Committee (CCC) report. A useful organization of deficits includes medical knowledge, clinical reasoning, organization and efficiency, professionalism, and interpersonal skills and communication.

Comprehensive assessment involves five elements.

Review of the fellowship file, including evaluations, standardized test scores, and application materials that address prior performance. Review of past performance is important to assess for change in learning trajectory, which may signal underlying issues with mental health and/or burnout. Disconnect between test scores and clinical performance may indicate a clinical reasoning deficit.

Communication with evaluators who have directly observed the learner’s performance.

Direct observation of the learner performing the skill in question.

-

Interview with the learner that accounts for diverse cultural factors that can influence performance and is focused on three areas:

assessment of the learner’s perception and insight into concerns;

exploration of stress, burnout, learning disability, and mental health issues; and

review of systems for each of the five major areas of deficit.

Assignment of a primary deficit to focus intervention.

If the assessment identifies concerns with mental wellbeing, appropriate referrals should be made before the initiation of a clinical coaching plan. If a learning disability is suspected, assistance from the appropriate professional(s) should be sought. In some cases, accommodations may be needed.

Coaching and Remediation of the Struggling Fellow

Outcomes data for remediation in internal medicine programs are limited to single-center experience and data reported in surveys of PDs (2–4). Hauer et al. (6) have proposed a model for remediation that involves deliberate practice of the skill in question, real-time feedback by a mentor who directly observes the learner, and reflection. In our experience, an individualized coaching plan should include the following.

No more than five specific and measureable goals for improvement

Description of coaching sites

Assignment of specific coaches

Timeline and process for reassessment

Consequences if goals are not met

Medical Knowledge

Approach to the fellow with a primary medical knowledge deficit begins with reviewing standardized test scores and assessment of reading and study habits. It is helpful to understand whether the problem is global or specific to particular clinical areas. Some fellows lack an effective system for studying and managing distractions, and others suffer from anxiety or poor self-confidence. After these issues are clarified, medical knowledge is fairly easy to remediate as long as there is learner motivation and buy in. Recommendations for reading should include review articles and a focus on symptom-based rather than disease-based learning (7). Practice questions, topic presentations, case discussions, and frequent review sessions with a coach can be helpful.

Organization, Efficiency, and Time Management

Senior fellows often serve as the best coaches for organization, efficiency, and time management. Coaching begins with direct observation of the fellow performing his/her daily work, focusing on prerounding and data collection, approach to new consults, triage of tasks, and note completion. Shadowing a senior fellow who effectively models efficiency can be invaluable. Additional orientation and shadowing can aid fellows not facile with the local electronic health record. In our experience, fellows who struggle with triage benefit from exercises in which a coach observes them assigning an urgency level to a list of tasks or provides feedback on their to do list regularly throughout the day.

Clinical Reasoning

The fellow with a primary clinical reasoning deficit often appears disorganized, struggles with patient presentations, and misses “the forest for the trees” with patients. Coaching begins with direct observation, usually by the supervising attending, to exclude more global deficits in organization and efficiency or medical knowledge. We find that clinical reasoning is initially best coached in an office setting by a faculty expert who reviews cases with the learner to pinpoint the area of struggle (i.e., data collection and synthesis, problem representation, building differential diagnosis, evaluation, or therapeutic decision making). The coach should focus on helping the learner develop illness scripts for commonly seen clinical scenarios. Illness scripts are one way that expert clinicians recall knowledge as diseases or presenting syndromes. Components of an illness script include predisposing risk factors, pathophysiology, and clinical presentation (8). Ideally, coaching then continues with direct observation of the fellow with new patients.

Professionalism

Professionalism challenges can be difficult to understand and assess. These typically manifest as deficiencies in meeting the trust placed in a professional (inadequate commitment to patient interests; failure to deliver in research, clinical, or social requirements; or lack of hard work) or insufficient application of virtue to practice (ineffective knowledge, attitudes, or skills to remain professional in complex adaptive situations) (9). Professionalism lapses assume that the learner is well intentioned but struggles to remain professional in trying circumstances (e.g., clinical environments) (10). Clear communication of expectations is essential for all professionals. Uncovering underlying thinking and self-insights from the learner is important. Objective data from behavior-based evaluations (written and obtained through interviews), multisource evaluations, and learner self-assessments can provide useful information and form observable markers for future expectations and assessments. Coaching should focus on ensuring that the learner incorporates proper knowledge (virtues), attitudes (professional identify), and skills (professional behaviors) into practice through discussion, reflection, problem-solving scenarios, and ultimately, actions in real clinical settings (9).

Interpersonal Skills and Communication

The fellow with communication concerns must be separated from those with professionalism deficiencies. Interpersonal problems often derive from challenges in understanding perspectives of others, interactions, and team dynamics. Pure communication deficiencies can include deficits in English comprehension and/or spoken and written English language skills as well as cultural differences. Such deficits can be addressed with communication skills training (8) and coaching with communication practice, direct observation, and feedback in clinical interactions.

Outcomes

Ultimately, review of assessment data for the fellow who has undergone clinical coaching is the responsibility of the PD. CCC assignment of milestones using objective evaluation data can be a valuable addition to outcomes of the coaching plan.

Fellows who struggle with clinical performance are challenging and time consuming. We believe a systematic approach better organizes the effort and allows program leaders to acquire experience and expertise over time. It is important to recognize that we, as educators, do not operate in a vacuum. As nephrologists working with struggling trainees, we should feel comfortable asking our colleagues in the Graduate Medical Education (GME) office for assistance and should be informed about relevant GME policies at our institutions. Dealing with the underperforming learner is rarely easy, but with proper effort and investment, the reward can be well worth the effort.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgment

The content of this article does not reflect the views or opinions of The American Society of Nephrology or the Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. Responsibility for the information and views expressed therein lies entirely with the author(s).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1. Warburton KM, Mahan JD for the ASN Workforce and Training Committee: Survey of training program directors, 2017. Available at: https://www.asn-online.org/membership/BlastEmails/files/2017%20Nephrology%20Training%20Program%20Retreat%20Presurvey-Results.pdf. Accessed September 1, 2017.

- 2.Guerrasio J, Garrity MJ, Aagaard EM: Learner deficits and academic outcomes of medical students, residents, fellows, and attending physicians referred to a remediation program, 2006-2012. Acad Med 89: 352–358, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dupras DM, Edson RS, Halvorsen AJ, Hopkins RH Jr., McDonald FS: “Problem residents”: Prevalence, problems and remediation in the era of core competencies. Am J Med 125: 421–425, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yao DC, Wright SM: National survey of internal medicine residency program directors regarding problem residents. JAMA 284: 1099–1104, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dudek NL, Marks MB, Regehr G: Failure to fail: The perspectives of clinical supervisors. Acad Med 80[Suppl]: S84–S87, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hauer KE, Ciccone A, Henzel TR, Katsufrakis P, Miller SH, Norcross WA, Papadakis MA, Irby DM: Remediation of the deficiencies of physicians across the continuum from medical school to practice: A thematic review of the literature. Acad Med 84: 1822–1832, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guerrasio J: Remediation of the Struggling Medical Learner, Irwin, PA, Association for Hospital Medical Education Press, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmidt HG, Rikers RM: How expertise develops in medicine: Knowledge encapsulation and illness script formation. Med Educ 41: 1133–1139, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brody H, Doukas D: Professionalism: A framework to guide medical education. Med Educ 48: 980–987, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Irby DM, Hamstra SJ: Parting the clouds: Three professionalism frameworks in medical education [published online ahead of print April 26, 2016]. Acad Med doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]