Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) is endemic in east Africa and is a leading cause of cancer death among Kenyans. The asymptomatic precursor lesion of ESCC is esophageal squamous dysplasia (ESD). We aimed to determine the prevalence of ESD in asymptomatic adult residents of southwestern Kenya.

METHODS

In this prospective, community-based, cross-sectional study, 305 asymptomatic adult residents completed questionnaires and underwent video endoscopy with Lugol’s iodine chromoendoscopy and mucosal biopsy for detection of ESD.

RESULTS

Study procedures were well tolerated, and there were no adverse events. The overall prevalence of ESD was 14.4% (95% CI: 10–19%), including 11.5% with low grade dysplasia and 2.9% with high grade dysplasia. The prevalence of ESD was >20% among men older than 50 years and women older than 60 years. Residence location was significantly associated with ESD (Zone A adjusted OR 2.37, 95% CI: 1.06–5.30, and Zone B adjusted OR 2.72, 95% CI: 1.12–6.57, compared to Zone C). Iodine chromoendoscopy with biopsy of unstained lesions was more sensitive than white light endoscopy or random mucosal biopsy for detection of ESD, and had 67% sensitivity and 70% specificity.

DISCUSSION

ESD is common among asymptomatic residents of southwestern Kenya, and is especially prevalent in persons over 50 years of age and those living in particular local regions. Lugol’s iodine chromoendoscopy is necessary for detection of most ESD but has only moderate sensitivity and specificity in this setting. Screening for ESD is warranted in this high-risk population, and endoscopic screening of Kenyans is feasible, safe, and acceptable, but more accurate and less invasive screening tests are needed.

Introduction

Esophageal cancer is the sixth-leading cause of cancer death in the world.1 Endemic regions with the highest rates of this cancer are found in central and eastern Asia and in eastern and southern Africa, and in these areas, about 90% of the cases are esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC).1–3 Esophageal cancer has a very poor prognosis because patients only develop symptoms at an advanced stage. The five-year relative survival rate for esophageal cancer in the US is 18%,4 and in most high-risk areas, where the medical infrastructure is less well developed, it is <5%.5 To improve this survival it is necessary to screen asymptomatic adults for curable precursor lesions and early stage cancers.6,7

ESCC is one of the leading causes of cancer among Kenyan adults, and it accounts for 31% of new cancer diagnoses at Tenwek Hospital in southwestern Kenya3 where this study was conducted. Esophageal squamous dysplasia (ESD) is the asymptomatic precursor lesion of ESCC, and the risk of progression depends greatly on the degree of dysplasia.8–10 The prevalence of ESD is around 30% in some asymptomatic high-risk Chinese populations,11,12 but the prevalence of ESD in asymptomatic high-risk African populations is unknown.

Various methods for diagnosis of ESD are available. Esophageal exfoliative cytology, endoscopy performed with standard white light, and random esophageal biopsy are not sufficiently sensitive to be used for population screening. 11–13 ESD is better detected by Lugol’s iodine chromoendoscopy or narrow band imaging with subsequent directed biopsy.13–15 Lugol’s chromoendoscopy, with biopsy of unstained regions, has the highest diagnostic yield in Asian studies.13,14 During endoscopy, normal esophageal mucosa stains darkly with iodine, while regions of ESD or esophagitis appear as “unstained lesions” (USLs).

Screening programs to detect and treat asymptomatic ESD have been shown to prevent cancer deaths in Asia, 6,7,16 and knowledge of the baseline prevalence and risk factors for ESD in east Africa could help determine whether similar screening programs are warranted in this region. In this study we aimed to determine the prevalence of ESD in asymptomatic adult residents. Secondary objectives were to characterize the histologic grade and location of dysplasia, to explore the sensitivity and specificity of Lugol’s unstained lesions for identifying mucosal areas with dysplasia, and to explore the impact of various risk factors (including age, sex, ethnicity, family history, tobacco use, ethanol use, and environmental exposures) on the prevalence of ESD.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

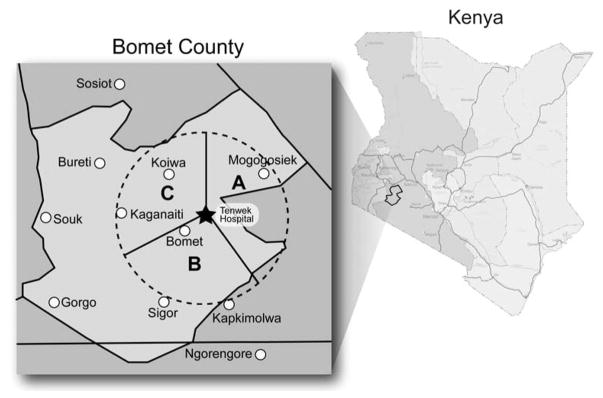

Between 2010 and 2013 we prospectively recruited 305 asymptomatic adult persons living in villages located within 50 km of Tenwek Hospital (latitude −0.745252, longitude 35.355892), in Bomet County, Kenya which has a population of 780,000, and assessed the presence of esophageal squamous dysplasia by performing upper gastrointestinal endoscopy with Lugol’s chromoendoscopy and mucosal biopsy in all study participants. This geographic area was divided into three traditional residence zones which together are demographically representative of Bomet county: Zone A (a highland fertile area with extensive tea and corn farms), Zone B (a dry and sandy area with wheat farms and herds of cattle and goats), and Zone C (a mixed dry and fertile area) (Figure 1). These zones are a traditional way to divide Bomet County, based on differences in climate, economic activities, agriculture, and animal husbandry, but not ethnicity. We aimed to enrol approximately equal numbers of subjects from each zone, gender, and age group (by decade of life). Recruitment went on simultaneously in the three zones, and was carried out in the villages of residence. Inclusion criteria included residence within 50 km of Tenwek Hospital, age 20–79 years, and a signed informed consent. Persons were specifically questioned about symptoms of dysphagia, odynophagia, hematemesis, or recent weight loss, and persons with any of these symptoms were excluded. Other exclusion criteria included allergy to iodine or lidocaine, and pre-existing medical conditions that would increase the risk of endoscopy (including bleeding disorders, heart arrhythmias, diabetes, lung disease or bleeding problems, or stroke). These inclusion and exclusion criteria were satisfied at the time of study enrolment.

Figure 1.

The study catchment area (red dashed circle), which was divided into zones A, B, and C.

The study was initially approved by the overall administrative head for the county. Subsequently, 23 village chiefs in the study region were approached regarding potential involvement of their village, and all who were approached gave permission. Once a chief decided that the study could include his village, study staff visited the village on a preannounced date and explained the study to all adult residents who chose to attend an informational meeting. The purpose and nature of the study were fully explained at these meetings, including the fact that participants would be evaluated for the presence of esophageal dysplasia and cancer. After the group informational meeting, those who wished to enrol had the study explained to them again individually, and then they were asked to sign a written informed consent. We estimate that about half of those who came to the informational meetings enrolled in the study. On the day of their study participation, the fasting study participants were transported to Tenwek Hospital for the study procedures, and they received a meal after recovering from endoscopy.

Procedures

On arrival at Tenwek Hospital, participants completed a questionnaire and provided blood and urine samples. The questionnaire collected information on demographic characteristics, living environment, farming practices, medical history, alcohol and tobacco use and dietary practices.

Participants then underwent video endoscopy of the esophagus (EG 250 WR5 Gastroscopes, Fujinon, Tokyo, Japan) with mapping and biopsy of visible lesions before and after staining of the mucosa with 1.4% Lugol’s iodine solution, as well as two random biopsies of normal appearing mid-esophageal mucosa. The endoscopic procedures were conducted under conscious sedation (intravenous diazepam or midazolam and fentanyl), with standard vital signs monitoring and post-endoscopy care. The study PI (MM) performed approximately 80% of the endoscopies, and four other endoscopists (SB, JL, RW, MT) performed the rest. During all endoscopies, two of the study endoscopists were present in the room, and they agreed on the locations and descriptions of the USLs and biopsy sites. After recovery from endoscopy, participants were asked to grade the level of discomfort they experienced. Endoscopic findings were recorded using standardized data forms, and abnormalities were characterized by their location (distance from the incisors and gastroesophageal junction), longitudinal extent, circumferential extent on the “clock face” of the esophageal lumen, estimated maximum diameter, macroscopic appearance, and uptake of Lugol’s iodine.

The histology of the study biopsies was read at the Department of Human Pathology, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya (JG and WW), and at the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, MD, USA (SMD), and discrepancies were adjudicated by joint consultation. Specimens were diagnosed using previously described criteria.17 Squamous dysplasia was characterized by nuclear atypia, loss of normal cellular polarity, and abnormal tissue maturation in the lower third (mild), lower two-thirds (moderate), or all thirds (severe) of the epithelium. Moderate and severe dysplasia were combined into one “high grade” dysplasia category for some data analyses. All participants were informed of their endoscopic and biopsy findings and those with ESD were counselled to pursue endoscopic or surgical therapy as appropriate. The study was approved by the Tenwek Hospital IRB and the Ethics Review Committee of the University of Nairobi- protocol number P172/06/2010. (Clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT01981876 )

Statistical analysis

The data were analysed both by biopsy site and by participant. For biopsy site analysis, we compared the endoscopic appearance, before and after staining, to the worst histological diagnosis from each site. We estimated the sensitivity and specificity for identifying mucosal areas with dysplasia using white light endoscopy (before staining) and after staining with Lugol’s iodine solution. We also evaluated the impact of mucosal staining on identifying patients with dysplasia.

In the participant analysis, participants were characterized based on their worst diagnosis as either having dysplasia (mild, moderate or severe dysplasia), or not (normal epithelium or esophagitis). We calculated the overall and 10-year age-specific prevalence of ESD. We tested for differences in participant characteristics between those with and without dysplasia using the χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test. Multivariate logistic regression was used to estimate odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for ESD. All statistical tests were 2-sided and p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

Results

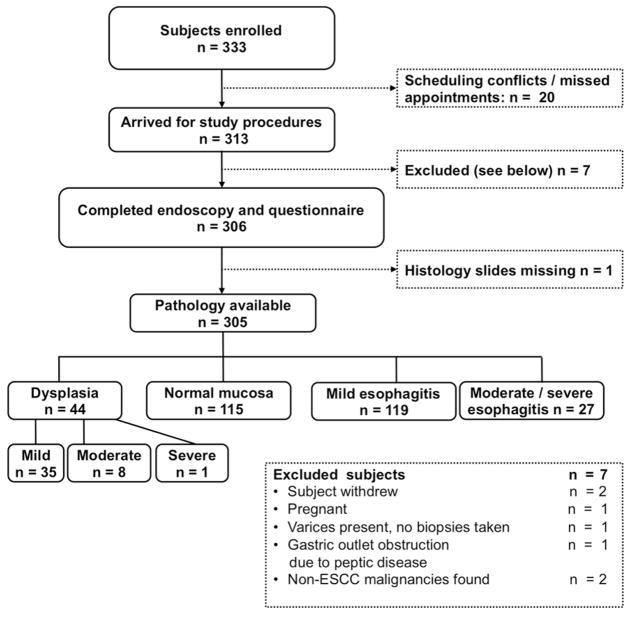

Of 333 enrolled subjects, 20 did not come to Tenwek Hospital for their study procedures (Figure 2). Of the remaining 313 participants, 305 (92%) completed the study endoscopy and were included in the analyses. Seven participants were excluded at the time of interview or endoscopy as shown in Figure 2, including 2 who were found to have non-ESCC malignancies during study endoscopy (one laryngeal cancer, one gastric antral cancer) and did not undergo chromoendoscopy. In addition histology slides were missing for one participant. Participant age ranged from 20 – 79 years, and the mean age (SD) was 46.7 (15.5) years. All were of Kalenjin ethnicity, and 163 (53%) were male (Table 1). Nineteen percent of the participants reported no discomfort during endoscopy, 80% reported mild discomfort, < 1% reported moderate discomfort, and none reported severe discomfort. There were no adverse events related to study procedures.

Figure 2.

Study Organizational Flow-chart.

Table 1.

Prevalence of esophageal squamous dysplasia, by participant characteristics, in the STEP study

| All | Worst Biopsy Diagnosis | Dysplasia prevalence % (95% CI) |

p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| n (%) | Normal (n=261) | Dysplasia (n=44) | |||

| Mean age (mean, SD) | 46.7 (15.5) | 46.0 (15.4) | 51.2 (15.3) | 0.04 | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 163 (53) | 137 | 26 | 16 (11–22) | |

| Female | 141 (46) | 124 | 18 | 13 (8–19) | 0.5 |

| Residence location | |||||

| A | 98 (32) | 79 | 19 | 19 (12–29) | |

| B | 61 (20) | 48 | 13 | 21 (12–34) | |

| C | 145 (48) | 133 | 12 | 8 (4–14) | 0.01 |

| Post primary education | |||||

| No | 200 (66) | 166 | 34 | 17 (12–23) | |

| Yes | 105 (34) | 95 | 10 | 10 (5–17) | 0.09 |

| Tobacco smokers | |||||

| No | 245 (80) | 214 | 31 | 13 (9–17) | |

| Yes | 60 (20) | 47 | 13 | 22 (12–34) | 0.1 |

| Alcohol drinkers | |||||

| No | 206 (68) | 185 | 21 | 10 (6–15) | |

| Yes | 98 (32) | 75 | 23 | 23 (16–33) | 0.003 |

| Family history of cancer | |||||

| No | 271 (89) | 232 | 39 | 14 (10–19) | |

| Yes | 34 (11) | 29 | 5 | 15 (5–31) | 1.00 |

| Family history of esophageal cancer | |||||

| No | 286 (94) | 243 | 42 | 15 (11–19) | |

| Yes | 19 (6) | 17 | 2 | 11 (1–33) | 1.00 |

Abbreviations: CI=confidence intervals

Fifty-two (7.4%) of the 698 sites biopsied in the study showed esophageal squamous dysplasia, including 43 with mild dysplasia, 8 with moderate dysplasia, and 1 with severe dysplasia. Eight subjects had dysplasia at more than one site, and no invasive ESCC was detected. Of the 52 dysplastic lesions, 2 (4%) were found in the upper third of esophagus (<25 cm from the incisors), 30 (58%) in the middle third (25–30 cm from the incisors), and 20 (38%) in the lower third (>30 cm from the incisors).

Categorized by their worst biopsy diagnosis, 115 (37.7%) participants had normal squamous mucosa, 146 (47.9%) had esophagitis, 35 (11.5%) had mild squamous dysplasia, 8 (2.6%) had moderate dysplasia, and 1 (0.3%) had severe dysplasia. Overall, 44 of the 305 participants had ESD, a prevalence of 14.4% (95% CI: 10–19%). The prevalence of ESD increased with age and exceeded 20% in men older than 50 and women older than 60 years (Table 2). While the dysplasia rate steadily increased with age among men, this was not apparent among women, possibly due to the modest number of dysplasia cases in the women.

Table 2.

Prevalence of esophageal squamous dysplasia by age and sex in the STEP study

| Characteristic | Worst Biopsy Diagnosis | Dysplasia Prevalence % (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Normal1 (n= 261) | Dysplasia2 (n=44) | ||

| Age | |||

| <30 | 49 | 3 | 6 (1–16) |

| 30–39 | 57 | 9 | 14 (6–24) |

| 40–49 | 39 | 6 | 13 (5–27) |

| 50–59 | 57 | 10 | 15 (7–26) |

| ≥60 | 59 | 16 | 21 (13–32) |

| Age: Male | |||

| <30 | 21 | 2 | 9 (1–28) |

| 30–39 | 31 | 4 | 11 (3–27) |

| 40–49 | 21 | 3 | 13 (3–32) |

| 50–59 | 29 | 8 | 22 (9–38) |

| ≥60 | 35 | 9 | 20 (10–35) |

| Age: Female | |||

| <30 | 28 | 1 | 3 (0.1–18) |

| 30–39 | 26 | 5 | 16 (5–34) |

| 40–49 | 18 | 3 | 14 (3–36) |

| 50–59 | 28 | 2 | 7 (1–22) |

| ≥60 | 24 | 7 | 23 (10–41) |

Abbreviations: CI=confidence intervals.

Includes normal squamous epithelium and esophagitis.

Includes mild, moderate and severe dysplasia

Table 3 shows the histology results from the 698 biopsy sites by endoscopic appearance before and after staining with Lugol’s iodine solution. Thirty-nine lesions were detected by white light endoscopy, 4 of which were dysplastic (3 mild and 1 moderate dysplasia). The sensitivity of white light endoscopy for detecting areas of dysplasia was 7.7% (95% CI: 2.2–18.6), the specificity was 94.6% (95% CI: 92.5–96.2), the positive predictive value (PPV) was 10.3% (95% CI: 2.9–24.2), and the negative predictive value (NPV) was 92.7% (95% 90.5–94.6). The sensitivity for detecting high grade (moderate or severe) dysplasia was 11.1% (95% CI: 1.8–48.3) and the specificity was 94.5% (95% CI: 95.5–96.1)

Table 3.

Squamous biopsy results by endoscopic appearance before and after Lugol’s staining in the STEP study

| Endoscopic appearance | No Dysplasia | Squamous biopsy results* | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild Dysplasia | Moderate Dysplasia | Severe Dysplasia | ||||

|

|

||||||

| Before staining | Visible lesion | 35 (5) | 3 (7) | 1 (13) | 0 (0) | 39 (6) |

| No visible lesion | 611 (95) | 40 (93) | 7 (87) | 1 (100) | 659 (94) | |

|

| ||||||

| Total | 646 | 43 | 8 | 1 | 698 | |

| After staining | Visible lesion (Unstained area) | 196 (30) | 29 (67) | 5 (63) | 1 (100) | 231 (33) |

| No visible lesion (Stained mucosa) | 450 (70) | 14 (33) | 3 (37) | 0 (0) | 467 (67) | |

|

| ||||||

| Total | 646 | 43 | 8 | 1 | 698 | |

Each biopsied site is presented as one entry in this analysis, with the percentage of sites in parentheses.

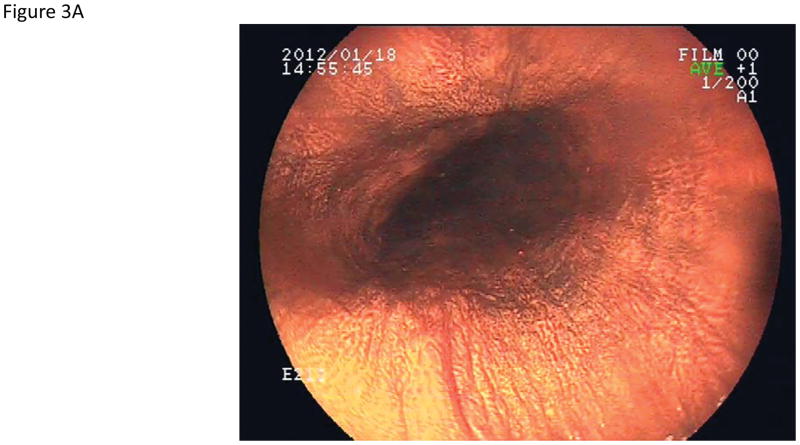

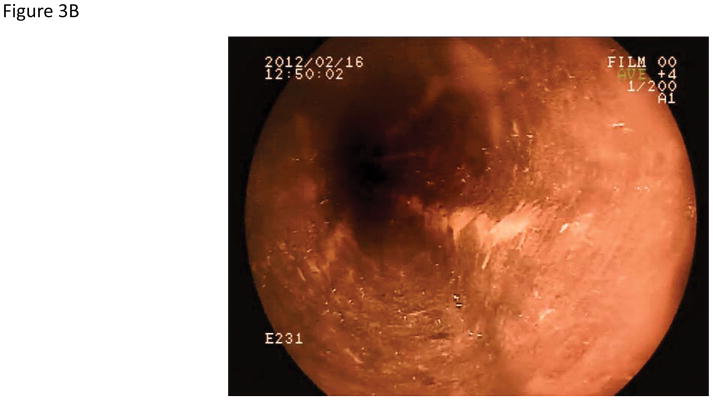

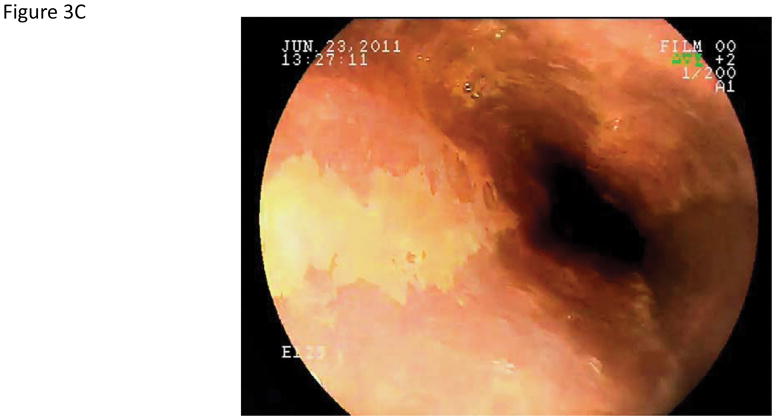

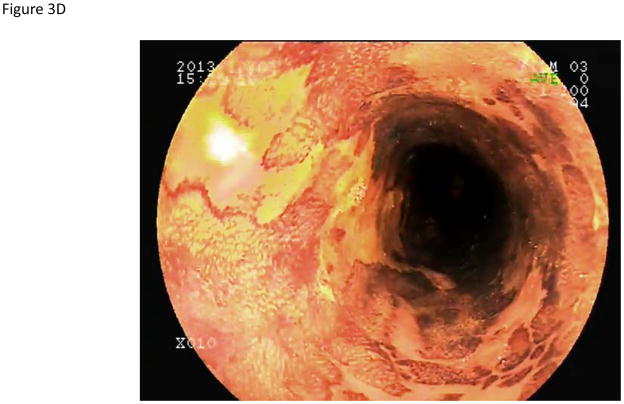

Using iodine chromoendoscopy, 231 unstained lesions (USLs) were detected (Table 3, Figure 3), 35 of which were dysplastic (29 mild, 5 moderate, and 1 severe dysplasia). In contrast to reports from China, we rarely saw large USLs such as those shown in Figure 3C and 3D. In 15% of cases USLs coalesced into a mosaic pattern (Figure 3D). The sensitivity of chromoendoscopy for detecting areas of dysplasia was 67.3% (95% CI: 53.9–79.7), the specificity was 69.7% (95% CI: 65.9–73.2), the PPV was 15.2% (95% CI: 10.8–20.4), and the NPV was 96.4% (95% CI: 94.2–97.9). The sensitivity and specificity for detecting high grade dysplasia were similar (66.7%, 95% CI: 30.1–92.1 and 67.3, 95% CI: 63.7–70.8, respectively).

Figure 3.

Endoscopic views of the esophagus with Lugol’s chromoendoscopy.

A) Normal esophageal mucosal staining. B) An unstained lesion (USL) surrounded by normally staining esophageal mucosa. Biopsies showed esophagitis. C) A USL with severe dysplasia on biopsy. D) Multiple USLs in a mosaic pattern. Biopsies showed severe dysplasia.

Table 4 shows the impact of staining on identifying patients with dysplasia. In 9.1% of the patients with dysplasia, the worst histologic lesion was visible by white light endoscopy; in 63.6%, the worst lesion was identified only after staining with Lugol’s iodine; and in 27.3%, the worst lesion was identified in normal-appearing and normally staining mucosa. Of the nine patients with high grade dysplasia, only one was identified before staining, four were identified only after staining, and three were identified by random biopsies of normal-appearing mucosa.

Table 4.

Impact of Lugol’s staining on the identification of patients with squamous dysplasia in the STEP study

| Worst patient diagnosis | Diagnostic lesion observed before stain | Diagnostic lesion observed only after stain | Diagnostic lesion not observed before or after stain | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild dysplasia | 3 | 23 | 9 | 35 |

| Moderate dysplasia | 1 | 4 | 3 | 8 |

| Severe dysplasia | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

|

| ||||

| Total | 4 (9.1) | 28 (63.6) | 12 (27.3) | 44 (100.0) |

The multivariate analysis of risk factors for ESD (Table 5) included factors that were statistically significant in table 1 and factors that have been associated with dysplasia risk in previous studies. In the multivariate analysis residence location was significantly associated with ESD (Zone A OR 2.37, 95% CI: 1.06–5.30, and Zone B OR 2.72, 95% CI: 1.12–6.57, compared to Zone C), and the association of alcohol use and ESD was nearly significant (OR 2.48, 95% CI 0.98–6.29). Post-primary education, tobacco use, and family history of cancer were not significantly associated with the prevalence of ESD. In a separate post-hoc analysis, the histologic finding of esophagitis did not affect the likelihood of dysplasia, which was present in 28/174 subjects with histologic esophagitis vs. 16/131 without esophagitis (p=0.41).

Table 5.

Univariate and multivariate odds ratios for risk factors for ESD in the STEP study

| Characteristic | Univariate OR (CI) | Multivariate OR (CI)1 |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 1.31 (0.68–2.50) | 0.95 (0.44–2.07) |

| Age >50 | 1.81 (0.94–3.45) | 1.34 (0.65–2.77) |

| Residence location | ||

| A (Fertile highlands) | 2.67 (1.23–5.78) | 2.37 (1.06–5.30) |

| B (Dry and sandy) | 3.00 (1.28–7.03) | 2.72 (1.12–6.57) |

| C (Mixed wet/dry) | Ref | Ref |

| Post-primary education | 0.51 (0.24–1.09) | 0.56 (0.25–1.25) |

| Tobacco use2 | 1.91 (0.93–3.93) | 0.89 (0.35–2.25) |

| Alcohol use3 | 2.70 (1.41–5.17) | 2.48 (0.98–6.29) |

| Family history of cancer | 1.03 (0.37–2.81) | 1.07 (0.34–3.38) |

| Family history of ESCC | 0.68 (0.15–3.07) | 0.60 (0.11–3.16) |

Abbreviations: OR=odds ratio, CI=confidence interval, ESD= esophageal squamous dysplasia

adjusted for the other variables listed in the table

at least once per day for six months

at least once per week for six months

Discussion

Esophageal squamous dysplasia (ESD) is the precursor lesion of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC). ESD is asymptomatic and difficult to detect by standard white-light endoscopy. This is the first African study to use Lugol’s iodine chromoendoscopy to screen for ESD. We found ESD in 14.4% of asymptomatic volunteers, including 35 (11.4%) with mild dysplasia and 9 (3%) with advanced (moderate or severe) dysplasia. The prevalence of ESD increased with age and was ≥ 20% in men age ≥ 50 years and women age ≥ 60 years. Geographic zone of residence was statistically associated with the prevalence of ESD. ESD is sufficiently common in our region to justify population-based screening, targeting persons at highest risk.

Although ESCC is endemic throughout much of east and southern Africa, there is little prior published data concerning ESD in the region. A study from South Africa that utilized endoscopic biopsies found ESD in only 0.7% of patients;18 autopsy studies conducted in South Africa demonstrated ESD in 3.2% – 7.5% of black residents.19,20 These early studies, which were performed over 2 decades ago, did not use current detection methods.

Our study probably underestimated the true prevalence of dysplasia, because over a quarter of detected cases were found on random biopsy of normal appearing and normally staining mid-esophageal mucosa, and similar dysplastic regions elsewhere in the esophagus would have been missed. Our observed ESD prevalence was lower than the 22% to 31% prevalence reported from most chromo-endoscopy screening studies in high-risk populations in China,11,12,21 and it was higher than the 6% ESD prevalence found in the one similar screening study reported from a high-risk population in Iran.22 This variation probably reflects population differences in underlying ESCC incidence, but it may also be partly due to other population differences (e.g. the age of those screened), differences in endoscopic techniques or the pathology criteria used, or differences in cancer biology in these countries. Compared to these previous endoscopic screening studies from other high risk areas, we saw a higher prevalence of ESD among young participants (8% in those <40 years of age), in keeping with our prior finding that a higher proportion of ESCC cases in south western Kenya occur in young people.3

Compared to white light endoscopy, Lugol’s chromoendoscopy significantly improved the sensitivity of detecting ESD. This is similar to the results of previous reports.13–15 In our study, Lugol’s chromoendoscopy had a 67% sensitivity for detecting all ESD, and the same 67% sensitivity for detecting advanced dysplasia (the most important target for screening).10,17,23 These figures were significantly less than the 82% sensitivity for all ESD and the 95% sensitivity for high-grade ESD that were previously reported from China.13 Possible reasons for these differences include suboptimal Lugol’s staining in some participants, different endoscopic equipment and personnel, population differences in how iodine stains the mucosa, or chance variation.

In our study, residence location was a significant risk factor for ESD. There were three main residence zones, which were different in terms of climate, soil, agriculture, and animal husbandry. It is not clear why residents of zones A and B had a higher risk of ESD and the multivariate model using the exposures listed in Table 1 shows that family history, tobacco, alcohol cannot explain the difference in prevalence between the regions. This notable difference in prevalence has stimulated future research to understand this difference

The high prevalence of dysplasia in this population justifies a screening program for detection and subsequent endoscopic treatment. However, endoscopic screening at a population level would be too costly and resource-intensive in our setting. Thus, there is a need to risk-stratify the population so that only the highest risk people need to undergo endoscopy. From our study results, it appears that some risk stratification could be achieved by targeting older age groups and individuals with certain risk factors such as alcohol drinking or residence in certain geographic regions, but previous studies have shown that stratification based on such factors achieves only modest efficiencies.23,24 What is probably needed is the development and use of a less invasive and less costly non-endoscopic primary screening method that would reliably pre-screen the population, identifying the individuals at highest risk and triaging them to endoscopy.

Strengths of this study include its prospective, community-based design, with enrolment of asymptomatic participants who were not seeking healthcare or undergoing endoscopy for clinical indications. In addition the multidisciplinary study team brought extensive endoscopy, pathology, and ESD research experience to bear on this work. Limitations of this study include limiting the study catchment area to one county in Kenya and a 50-km radius. This was done in order to obtain a truly community-based assessment of a region; however it is unclear if our results apply to other regions and ethnicities. Additionally, participants were fully informed about the nature of the study before enrolment, introducing the possibility of selection bias. It is unlikely that self-selection due to unreported symptoms was common, since dysplasia is completely asymptomatic and no occult cancers were found. Family history of cancer, however, could have motivated volunteering for screening, and this would have introduced a referral bias.

In conclusion, endoscopic screening of asymptomatic adults for ESD and early esophageal cancer is feasible, safe, and patient-acceptable in this high-risk African population. Lugol’s staining increases the sensitivity of screening and is necessary for visual detection of most cases of squamous dysplasia, but has only moderate sensitivity and specificity for detection of ESD in our region. Further investigations are needed to understand the differences in dysplasia prevalence in the different geographic regions of our study area. Findings from this study will help to refine the design of screening and intervention programs for ESD and esophageal cancer in east Africa.

Study highlights.

What is current knowledge

Esophageal squamous dysplasia (ESD) is the precursor lesion of esophageal squamous cell cancer (ESCC)

ESD can be visually localized by Lugol’s chromoendoscopy

In endemic Asian regions ESCC incidence and mortality have been reduced by endoscopic screening and treatment of ESD.

ESCC is a leading cause of cancer death in Eastern and Southern Africa, but there are no studies assessing the prevalence of ESD in sub-Saharan Africa utilizing current diagnostic methods

What is new here

ESD is common in an asymptomatic African population at high risk for ESCC, with prevalence over 20% in men over 50 and women over 60 years of age.

Lugol’s chromoendoscopic screening for ESD is feasible, safe, and acceptable in an African setting.

The sensitivity of Lugol’s chromoendoscopy for detection of ESD was lower in this study than in Asian studies (67% compared to 80%–95%)

Acknowledgments

Financial support: BIG CAT (Beginning Investigator Grant for Catalytic Research) grant from the African Organization for Research and Training in Cancer (AORTIC) and the U.S. National Cancer Institute (NCI).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

Guarantor of the article: Michael M Mwachiro, MBChB

Specific author contributions: Study design: Michael M Mwachiro, Stephen L Burgert, Christian C Abnet, Russell E White, Mark D Topazian, Sanford M Dawsey. Study oversight: Michael M Mwachiro, Stephen L Burgert, Russell E White, Mark D Topazian, Sanford M Dawsey. Endoscopic oversight and quality analysis: Stephen L Burgert, Russell E White, Mark D Topazian, Sanford M Dawsey. Endoscopic procedures and data collection: Michael M Mwachiro, Stephen L Burgert, Justus Lando, Robert Chepkwony, Collins Bett, Russell E White, Mark D Topazian. Pathology oversight and quality analysis: Jessie Githanga, Wairimu Waweru, Sanford M Dawsey. Data analysis: Michael M Mwachiro, Claire Bosire, Christian C Abnet, Carol A Giffen, Gwen Murphy. All authors approved the final draft submitted.

Potential competing interests: None

References

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Islami F, Kamangar F, Aghcheli K, et al. Epidemiologic features of upper gastrointestinal tract cancers in Northeastern Iran. Br J Cancer. 2004;90(7):1402–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parker RK, Dawsey SM, Abnet CC, White RE. Frequent occurrence of esophageal cancer in young people in western Kenya. Dis Esophagus. 2010;23(2):128–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2009.00977.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(1):5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aghcheli K, Marjani HA, Nasrollahzadeh D, et al. Prognostic factors for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma--a population-based study in Golestan Province, Iran, a high incidence area. PLoS One. 2011;6(7):e22152. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang G, Jiao G, Chang F, et al. Long-term results of operation for 420 patients with early squamous cell esophageal carcinoma discovered by screening. Ann Thoracic Surgery. 2004;77:1740–4. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.10.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wei WQ, Chen ZF, He YT, et al. Long-Term Follow-Up of a Community Assignment, One-Time Endoscopic Screening Study of Esophageal Cancer in China. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(17):1951–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.0423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang G, Abnet CC, Shen Q, et al. Histological precurors of oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma: results from a 13 year prospective follow up study in a high risk population. Gut. 2005;54:187–92. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.046631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor PR, Abnet CC, Dawsey SM. Squamous dysplasia--the precursor lesion for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22(4):540–52. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dawsey SM, Lewin KJ, Wang GQ, et al. Squamous esophageal histology and subsequent risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. A prospective follow-up study from Linxian, China. Cancer. 1994;74(6):1686–92. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940915)74:6<1686::aid-cncr2820740608>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pan QJ, Roth MJ, Guo HQ, et al. Cytologic detection of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and its precursor lesions using balloon samplers and liquid-based cytology in asymptomatic adults in Llinxian, China. Acta Cytol. 2008;52(1):14–23. doi: 10.1159/000325430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roth MJ, Liu SF, Dawsey SM, et al. Cytologic detection of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and precursor lesions using balloon and sponge samplers in asymptomatic adults in Linxian, China. Cancer. 1997;80(11):2047–59. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19971201)80:11<2047::aid-cncr3>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dawsey SM, Fleischer D, Wang G, et al. Mucosal iodine staining improves endoscopic visualization of squamous dysplasia and squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus in Linxian, China. Cancer. 1998;83:220–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang LY, Cui J, Wu CR, Liu YX, Xu N. Narrow-band imaging in the diagnosis of early esophageal cancer and precancerous lesions. Chin Med J (Engl) 2009;122(7):776–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lopes AB, Fagundes RB. Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma - precursor lesions and early diagnosis. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;4(1):9–16. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v4.i1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang S, Wu M, Zhang L, et al. The value of endoscopic mucosal resection for dysplasia and early-stage cancer of the esophagus and gastric cardia. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2008;30(11):853–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dawsey SM, Lewin KJ, Liu FS, Wang GQ, Shen Q. Esophageal morphology from Linxian, China. Squamous histologic findings in 754 patients. Cancer. 1994;73(8):2027–37. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940415)73:8<2027::aid-cncr2820730803>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jaskiewicz K, Louwrens HD, Van Wyk MJ, Woodroof CL. Oesophageal mucosal pathology in a population at risk for gastric and oesophageal carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 1989;9(4):1191–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dreyer L. The incidence of dysplasia and associated epithelial lesions in the oesophageal mucosa of South African Blacks. S Afr Med J. 1980;58(10):406–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaskiewicz K, Banach L, Mafungo V, Knobel GJ. Oesophageal mucosa in a population at risk of oesophageal cancer: post-mortem studies. Int J Cancer. 1992;50(1):32–5. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910500108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu XJ, Chen ZF, Guo CL, et al. Endoscopic survey of esophageal cancer in a high-risk area of China. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10(20):2931–5. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i20.2931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roshandel G, Khoshnia M, Sotoudeh M, et al. Endoscopic screening for precancerous lesions of the esophagus in a high risk area in Northern Iran. Arch Iran Med. 2014;17(4):246–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wei WQ, Abnet CC, Lu N, et al. Risk factors for oesophageal squamous dysplasia in adult inhabitants of a high risk region of China. Gut. 2005;54(6):759–63. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.062331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Etemadi A, Abnet CC, Golozar A, Malekzadeh R, Dawsey SM. Modeling the risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and squamous dysplasia in a high risk area in Iran. Arch Iran Med. 2012;15(1):18–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]