Abstract

Background/Aims

Although gastric cancer (GC) prevalence in the United States overall is low, there is significantly elevated risk in certain racial/ethnic groups. Providers caring for high-risk populations may not be fully aware of GC risk factors and may underestimate the potential for selective screening. Our aim was to identify knowledge gaps among healthcare providers with respect to GC.

Methods

An Internet-based survey was distributed to primary care providers (PCPs) and gastroenterologists in New York City, which included questions regarding provider demographics, practice environment, GC risk factors, Helicobacter pylori, and screening practices. Three case vignettes were used to assess clinical management.

Results

Of 151 included providers (111 PCPs, 40 gastroenterologists), most reported caring for a racially/ethnically diverse population and 58% recommended GC screening for select populations. Although >85% recommended against testing patients from regions where H. pylori, a known carcinogen, is endemic, <50% were able to correctly identify non-Asian endemic regions. Minorities of respondents correctly identified Hispanic/Latino (29%), Black (22%), and Eastern European/Russian (19.7%) as additional higher-risk races/ethnicities. Vignette-based questions highlighted variability in the management of potentially higher-risk patients.

Conclusions

Despite caring for multiracial/ethnic populations, providers demonstrated deficiencies in identifying and managing patients with elevated GC risk. Focused educational efforts should be considered to address these deficiencies.

Keywords: Stomach neoplasms, Mass screening, Helicobacter pylori

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer (GC) is a leading cause of death worldwide and is most prevalent in East Asia (specifically Japan, Korea, and China), South/Central America, and parts of Eastern/Central Europe.1 The United States (US) is generally considered a low-prevalence country for GC. However, there is variation in incidence and mortality among different racial/ethnic populations, with the highest incidence amongst Asian-American, Hispanic/Latino, and Black populations. GC prevalence rates in these groups is two to three times higher than the US-born White population, and even approaches rates comparable to endemic countries.2,3 The ideal way to reduce GC mortality is through early detection and treatment of early stage cancers and is the primary goal of screening programs. However, in the US, screening for GC amongst high-risk individuals does not routinely occur.

At over 37%, New York City (NYC) has one of the highest foreign-born populations in the US.4 Importantly, over 75% of the foreign-born population comes from high prevalence areas for GC. Studies have shown that these higher risk ethnic populations have a similar risk for GC as their native countries.4–8 Indeed, the incidence of GC in Korean-Americans is similar to the incidence of colorectal cancer in the US population—a cancer routinely screened for in the US—and is estimated to be over five times higher than the incidence of noncardia GC among non-Hispanic Whites.3 As such, it is reasonable to follow the GC screening guidelines implemented in Korea and Japan for their respective immigrant counterparts in the US (and likely other high risk racial/ethnic groups). Extrapolating a model of targeted screening for high-risk groups may not only improve early GC detection rates and decrease GC related mortality, it may also be highly cost-effective if appropriately implemented.9

Screening programs in high-risk countries are effective and have been associated with reduced GC-related mortality, as evidenced by Japan and Korea where national screening guidelines for GC exist and are routinely implemented.10–15 Based on this practice and evidence, the Standards of Practice Committee of the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) released a guideline statement which recommended considering screening new US immigrants above the age of 40 from high-risk endemic regions (Japan, Korea, China, Russia, and South America) for GC with upper endoscopy, particularly in those with first-degree relatives with a history of GC.16 Notably, the society made no mention of recommendations for other high-risk groups in the US, including future-generation immigrants from endemic areas, Hispanic/Latinos and Black Americans, despite acknowledging their significantly higher incidence of GC compared to US-born Whites. This is the only clinical guidance with respect to GC screening in the US currently. Actual implementation of this recommendation with referral of high-risk patients to gastroenterology (GI) clinics by primary care providers for screening and uptake amongst gastroenterologists has not been studied.

Atrophic gastritis (AG), intestinal metaplasia (IM), and dysplasia of the stomach are precancerous changes that are believed to progress in a stepwise fashion over time to intestinal-type GC.17 Infection with Helicobacter pylori is considered the primary trigger for these preneoplastic changes by first inducing a chronic gastritis that, in a minority of patients, progresses to preneoplasia and potentially intestinal-type GC.18–20 H. pylori was recognized as a class I carcinogen by the World Health Organization in 1994 and is the most common infectious cause of cancer, above hepatitis B virus for hepatocellular carcinoma and human papilloma virus for cervical cancer.21,22 Additional risk factors for GC include family history of GC, smoking, diet high in salted/preserved or low in fiber foods, blood type A, and prior gastric surgery. Whether race/ethnicity itself is an intrinsic risk factor for gastric preneoplasia has not been clarified and is difficult to determine given the marked variation in ethnicity and in H. pylori prevalence around the world.

As noted, high-risk patients are not referred to GI specialty clinics for GC screening even though their risk of GC is comparable to, if not higher than, the risk of colorectal cancer in the US population. We postulated that there is a lack of awareness by both the provider and patient regarding those who are at higher risk for developing GC and, similarly, a lack of awareness of GC screening recommendations. Accordingly, we hypothesized that there is a substantial need to enhance GC education and awareness for screening high-risk populations, especially in a multiethnic region like NYC. We therefore designed a survey for NYC health care providers, both primary care physicians and gastroenterologists, to assess the magnitude of this knowledge gap with the overall intent of having the survey findings inform future educational initiatives for providers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Study design

This project was approved by the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Institutional Review Board. We designed an internet-based survey (http://www.surveymonkey.com) with clinical, demographic, and practice-environment focused questions, as well as specific questions assessing providers’ knowledge of GC risk factors, H. pylori, screening practices (or lack thereof), and three short vignette-style questions assessing management decisions. Participation in this study was voluntary and responses remained anonymous. Providers were neither provided with material incentive to participate, nor were they penalized for their decision not to participate. Primary care physicians (internal medicine, and family medicine) and gastroenterologists affiliated with academic institutions in NYC were e-mailed an invitation to participate in the survey.

2. Demographic and basic practice environment assessment

Participants were first asked about their provider type (physician, nurse practitioner [NP], physician assistant [PA], registered nurse, and other) and practice type (internal/family medicine, GI, and other), as well as training status (resident/fellow/faculty). Subsequent questions asked for providers’ demographics (sex, and race/ethnicity) and also their patient population demographic. For the latter, we asked whether their practice consisted of at least 10% to 30% Hispanic/Latino, Black, first-generation Asian (including Japanese and Korean), first-generation Russian, first-generation Eastern European (E. European), US-born White, and other (with free text option).

3. Provider practice and knowledge assessment (non-vignette)

Participants were asked questions about GC risk factors, H. pylori-related questions (endemic areas, risk factors for infection, status as a carcinogen, types of tests for H. pylori, and whether the provider recommends H. pylori screening and treatment), types of gastric preneoplasia, as well as questions asking providers’ practice with respect to routine GC screening. If they do screen, providers were asked which modalities they use (e.g., endoscopy, contrast imaging, H. pylori testing, and other) (Supplementary Material).

4. Provider practice and knowledge assessment (vignette)

Three vignette-based questions assessed provider management and follow-up of patients potentially at increased risk for GC (Supplementary Material).

5. Additional questions

To help inform future educational outreach efforts, the final two questions asked whether participants would be interested in learning more about this topic and, if so, which learning modality they preferred.

6. Statistical analyses

Data collected in SurveyMonkey was exported to Excel version 2011 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA) and then imported into SPSS version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) for descriptive and univariate analysis. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Among 557 potentially eligible participants, 160 responded (28.7%) to the e-mail invitation. After excluding three non-physicians (two NPs and one PA), three oncologists (i.e., non-primary provider, and non-gastroenterologist), and three participants who did not complete the survey after accepting, 151 (27.1%) remained for formal analysis. Because there was no difference in responses between residents/fellows and faculty in either gastroenterologist or primary care provider type, provider categories were simply categorized as “gastroenterologist” or “primary care physician.”

1. Demographic and basic practice environment

Of the 151 physicians, 111 (73.5%) identified as primary care physicians and 40 (26.4%) as gastroenterologists (Table 1). With respect to provider demographic, 53.7% identified as male. The race/ethnicity of the providers themselves were as follows: White (61.5%), Asian (31.1%), Black (4%) and Hispanic/Latino (7.3%). Providers reported that their patient population consisted of at least 10% to 30% of the following race/ethnicities: Blacks (80%), Hispanic/Latinos (86.9%), and first-generation Asian immigrants (26.8%)—including first-generation Korean and Japanese immigrants (9.7%)—and first-generation Russian or E. European immigrant patients (31%).

Table 1.

Provider Demographics and Practice Environment

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Provider type | |

| Primary care physician (internal/family medicine) | 111/151 (73.5) |

| Gastroenterologist | 40/151 (26.4) |

| Provider sex | |

| Male | 81/151 (53.7) |

| Female | 70/151 (46.3) |

| Provider demographic | |

| White | 93/151 (61.5) |

| Asian | 47/151 (31.1) |

| Hispanic/Latino* | 11/151 (7.3) |

| Black | 6/151 (4) |

| Providers with a patient demographic consisting of >10%–30% of their total patients | |

| Black | 116/145 (80) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 126/145 (86.9) |

| Asian immigrants (G1) | 39/145 (26.8) |

| Korean or Japanese immigrants (G1) | 14/145 (9.7) |

| Russian/Eastern Europeans immigrants (G1) | 45/145 (31) |

Data are presented as number/total number (%).

G1, first-generation.

Includes White (n=2), Black (n=1), and race unspecified (n=4).

2. Provider practice and knowledge assessment (non-vignette)

Of all respondents, 18 (11.9%) believed that screening for GC should not be recommended for anyone in the US and an almost equal amount 17 (11.3%) believed it should be recommended. The majority of respondents (58.3%) believed that screening should be recommended for select populations, with no difference in response according to provider type or provider demographic. Those providers caring for at least 10% to 30% first-generation Asian immigrants were significantly more likely to favor screening in some populations (p=0.01). Providers caring for at least 10% to 30% Hispanic/Latinos, Blacks, and Russian/E. European first generation immigrants were more likely to favor screening in some populations compared to those caring for <10% of this demographic, but this was not statistically significant (Table 2). When asked about appropriate screening modalities, the majority selected upper endoscopy (84.1%), while one-third inappropriately selected H. pylori testing (33.3%).

Table 2.

Screening for Gastric Cancer: Providers’ Responses

| Total | Screening should not be recommended | Screening should be recommended | Screening should be recommended in some populations | Unsure/no response | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provider type | 0.11 | |||||

| Gastroenterologist | 40 | 4 (10.0) | 1 (2.5) | 29 (72.5) | 6 (15.0) | |

| Primary care | 111 | 14 (12.6) | 16 (14.4) | 59 (53.2) | 22 (19.8) | |

| Provider demographic | 0.23 | |||||

| Hispanic/Latino* | 11 | 3 (27.3) | 1 (9.1) | 6 (54.5) | 1 (9.1) | |

| Asian | 47 | 4 (8.5) | 6 (12.8) | 30 (63.8) | 7 (14.9) | |

| Black | 6 | 3 (50.0) | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 2 (33.3) | |

| White | 93 | 10 (10.8) | 11 (11.8) | 54 (58) | 18 (19.4) | |

| Patient demographic (>/= 10%–30%) | ||||||

| Asian (G1) | 39 | 2 | 9 | 23 (59.0) | 5 | 0.01 |

| Hispanic/Latino (G1) | 126 | 15 | 14 | 75 (59.5) | 22 | 0.65 |

| Black | 116 | 15 | 12 | 70 (60.3) | 19 | 0.87 |

| Russian (G1) | 18 | 1 | 2 | 13 (72.2) | 2 | 0.75 |

| Eastern European (G1) | 27 | 2 | 3 | 20 (74.1) | 2 | 0.47 |

Data are presented as number (%) or number.

G1, first-generation.

Includes White (n=2), Black (n=1), and race unspecified (n=4).

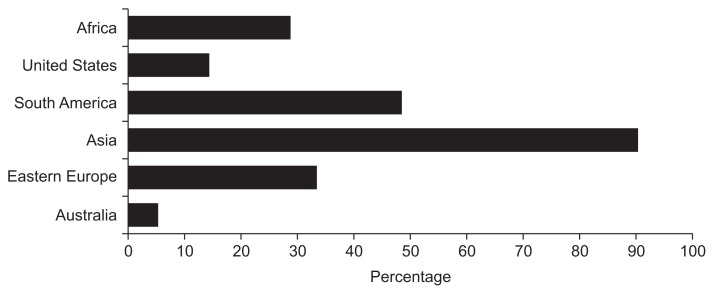

Although the vast majority of providers (92%) correctly identified H. pylori as a carcinogen, the 11 providers who answered incorrectly were all primary care physicians (p=0.04) (Table 3). Over 62% of gastroenterologists believed that patients at increased risk for H. pylori should be screened, compared to only 11.6% of primary care physicians (p<0.001). Overall, over 85% of providers (88.4% gastroenterologists, 78.4% primary care) answered that they do not routinely test and treat for H. pylori in patients from endemic regions who are otherwise asymptomatic. While 90% of respondents correctly identified Asia as an endemic area for H. pylori, less than half of respondents were able to correctly identify Eastern Europe (32.3%) and South America (48.5%) as endemic areas (Fig. 1), despite an H. pylori prevalence of at least 70% to 80% in these areas.23

Table 3.

Management of High-Risk Populations: Providers’ Responses

| H. pylori is a carcinogen | p-value | Endemic populations should be tested and treated for H. pylori if positive | p-value | Routinely screen patients considered high-risk for H. pylori | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| True | False | Agree | Disagree | Agree | Disagree | ||||

| Provider type | 0.04 | 0.14 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Gastroenterologist | 38/38 (100) | 0/38 (0) | 11/95 (11.6) | 84/95 (88.4) | 23/37 (62.2) | 14/37 (37.8) | |||

| Primary care | 93/104 (89.4) | 11/104 (10.6) | 8/37 (21.6) | 29/37 (78.3) | 11/95 (11.6) | 84/95 (88.4) | |||

| Provider demographic | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.46 | ||||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 9/10 (90.0) | 1/10 (10.0) | 1/8 (12.5) | 7/8 (87.5) | 2/8 (25.0) | 6/8 (75.0) | |||

| Asian | 43/46 (93.5) | 3/46 (6.5) | 3/43 (7.0) | 40/43 (93.0) | 13/43 (30.2) | 30/43 (69.8) | |||

| Black | 4/6 (66.7) | 2/6 (33.3) | 0/4 (0) | 4/4 (100) | 1/4 (25.0) | 3/4 (75.0) | |||

| White | 81/88 (92.0) | 7/88 (8.0) | 15/83 (18.1) | 68/83 (81.9) | 21/83 (25.3) | 62/83 (74.7) | |||

| Patient demographic (>/= 10%–30%) | |||||||||

| Asian (G1) | 36/37 (97.3) | 1/37 (2.7) | 0.27 | 8/35 (22.9) | 27/35 (77.1) | 0.15 | 10/35 (28.6) | 25/35 (71.4) | 0.66 |

| Hispanic/Latino (G1) | 114/123 (92.7) | 9/123 (7.3) | 0.68 | 17/115 (14.8) | 98/115 (85.2) | 0.76 | 27/115 (23.5) | 88/115 (76.5) | 0.03 |

| Black | 107/115 (93.0) | 8/115 (7.0) | 0.97 | 17/107 (15.9) | 90/107 (84.1) | 0.35 | 24/107 (22.4) | 83/107 (77.6) | 0.04 |

| Russian (G1) | 17/18 (94.4) | 1/18 (5.6) | 0.88 | 6/17 (35.3) | 11/17 (64.7) | 0.01 | 6/17 (35.3) | 11/17 (64.7) | 0.31 |

| Eastern European (G1) | 25/27 (92.6) | 2/27 (7.4) | 0.82 | 8/25 (32.0) | 17/25 (68.0) | 0.01 | 11/25 (44.0) | 14/25 (56.0) | 0.02 |

Data are presented as number (%).

H. pylori, Helicobacter pylori; G1, first-generation.

Fig. 1.

Providers’ responses to “Which of the following are endemic areas for Helicobacter pylori?”

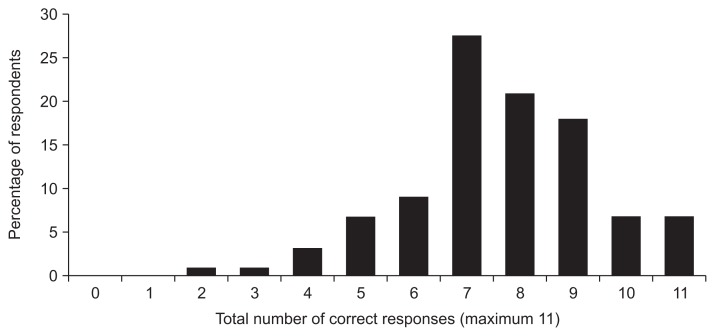

With respect to GC risk factors, the majority of respondents correctly identified IM (70.4%) and dysplasia (88%) as preneoplastic lesions for intestinal-type GC, but only 38% correctly identified AG as such. All three preneoplastic lesions were correctly identified by 42.5% of gastroenterologists compared to 18.9% primary care physicians (p=0.003). The majority correctly identified age (77.2%), male sex (91.9%), smoking tobacco (98.5%), H. pylori (95.6%), family history (96.3%), eating preserved/smoked foods (91.9%), and blood type A (69.9%) as risk factors for GC. Although not clearly related to noncardia GC, 84.5% and 61% of respondents reported alcohol and obesity as risk factors. Only 22% correctly identified excess salt intake and only 36% correctly identified prior gastric surgery as risk factors. Of 11 risk factors for GC listed in the question stem, fewer than 7% of providers were able to identify all 11 risk factors, although the majority of respondents (79.8%) were able to identify at least seven of the 11 listed risk factors (Fig. 2). There was no difference in ability to identify these risk factors according to provider type or patient demographic (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Providers’ correct identification of gastric cancer risk factors. Fewer than 7% of providers were able to identify all 11 risk factors for gastric cancer that were listed in a survey question. Nearly 80% (79.8%) of providers could identify at least seven of the 11 listed risk factors.

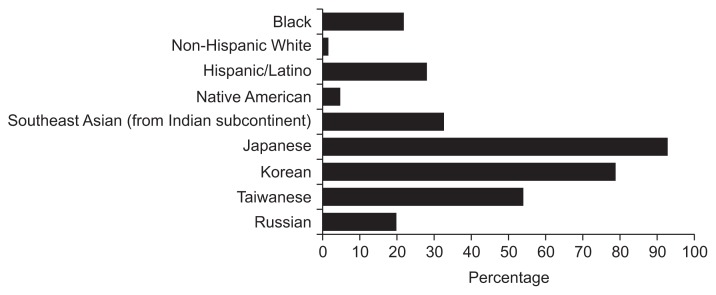

In terms of high-risk races/ethnicities, the majority correctly identified Japanese (92.2%) and Korean (78.8%) as high-risk for GC, but only a minority of providers were able to correctly identify Hispanic/Latinos (28%), Blacks (22%), and first generation Russian/E. Europeans (19.7%) as high-risk groups. Less than 5% correctly identified Native Americans as high-risk (4.6%) (Fig. 3). There was no difference between gastroenterologists’ and primary care physicians’ ability (or lack thereof) to correctly identify high-risk races/ethnicities (p=NS).

Fig. 3.

Providers’ responses to “Which of the following races/ethnicities are at high risk for gastric cancer?”

3. Provider practice and knowledge assessment (case vignettes)

In case 1, which described a 47-year-old White man with acute GI bleeding due to a gastric ulcer which was endoscopically and medically treated (H. pylori negative), only 58.6% of providers correctly answered continue proton pump inhibitor (PPI) two times per day for 6 to 8 weeks and repeat esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) in 6 to 8 weeks to confirm ulcer healing. Nearly 30% incorrectly chose repeat EGD only if the patient was symptomatic. Nearly all gastroenterologists (94.6%) chose the correct management compared to 44% of primary physicians (p<0.00001).

Case 2 described a 50-year-old Russian man with no other GC risk factors, who was found on EGD with random biopsies (for nonulcer dyspepsia) to have H. pylori negative IM without dysplasia. Given that the guidelines are unclear regarding this patient’s management,24 the authors (S.C.S. and S.H.I.) chose a priori that EGD with mapping biopsies in 1 to 3 years with or without H. pylori treatment empirically are acceptable answers. There was wide variation in selecting the next “best step in management,” with the most common response being daily PPI therapy and repeating EGD in 1 year with mapping biopsies (30.4%); 18.4% chose repeating EGD in 1 year with mapping biopsies alone and 6.4% incorrectly chose PPI alone without additional management. Overall, less than 30% of gastroenterologists (27%) answered correctly while only 5.7% of primary care physicians answered correctly (p=0.001).

The final case vignette described a 60-year-old White woman from NYC who was found on anemia workup to have grossly normal EGD but with biopsies showing complete IM, H. pylori positive, and otherwise no other GC risk factors. The majority (46.3%) correctly answered treat for H. pylori and then consider repeat endoscopy nonurgently with mapping biopsies (40.5% gastroenterologists vs 48.8% primary care provider, p=0.40), while 36.6% would just treat H. pylori, confirm eradication and not repeat the EGD. About 6% would treat H. pylori and prescribe PPI therapy, while 9.8% recommended treating H. pylori with no further follow-up. Two people notably chose not to treat H. pylori and both were gastroenterologists (Supplementary Material).

4. Continuing medical education

Nearly 90% responded that they would be interested in learning more about GC and GC screening for high-risk patients. Preferred modalities included grand rounds/continuing medical education (CME) course (68%), small-group lecture or workshop (50.5%), and web-based learning modules (47.7%) compared to e-mail (25.2%), pamphlets/flyers (6.5%), and health fairs (2.8%).

DISCUSSION

In this survey of gastroenterologists and primary care health care physicians based in NYC, we found significant knowledge gaps with respect to both knowledge of GC risk factors and management of patients at potentially increased risk. While several deficiencies were more apparent amongst primary care physicians than gastroenterologists, there were many shared deficiencies, underscoring the need to educate both groups of providers. We achieved the primary aim of this study, which was to identify points of intervention and education for both gastroenterologists and primary care physicians practicing in NYC with respect to GC and associated risk factors given the high immigrant and multiethnic/racial population.

In high-risk regions of the world such as East Asia, GC screening efforts have resulted in reduction of GC-related mortality by at least 50% to 60%, which has been attributed to earlier detection and opportunity for curable resection.10–14 Accordingly, the ASGE Standards of Practice Committee suggest considering GC screening for new US immigrants over 40 years-old who are from certain high-risk endemic areas, although they do not offer recommendations for other high-risk groups in the US, particularly other racial/ethnic and future-generation immigrants.16 No other GI society or general medicine guidelines address GC screening in the US. Since the majority of respondents believed that screening selected populations at increased risk for GC is appropriate, this suggests that there is at least an awareness amongst providers that there are relative higher risk subgroups who may benefit from screening despite the overall low prevalence of GC in the US. That said, the majority of these providers were gastroenterologists, as only 11.6% of primary care physicians felt that select populations should be considered for GC screening. While there is at least some recognition of the disparity in GC prevalence in the US, the results of this survey indicate that providers have an insufficient understanding of the reasons underlying the disparity such as racial/ethnic differences in GC prevalence.

While infection with H. pylori is the strongest known risk factor for GC, over 10% of primary care providers caring for a multiethnic population at higher risk for H. pylori infection and thus GC, did not identify it as such. The great majority of providers stated that they do not routinely test and treat H. pylori in individuals from endemic regions, despite strong evidence that H. pylori eradication prior to the development of preneoplasia decreases GC risk, and may potentially decrease risk of progression once preneoplasia has developed.20,25 Asia-Pacific GC consensus guidelines advocate screening for H. pylori infection in high-risk countries, and the ASGE acknowledges the disparity in H. pylori prevalence within the US.15,16 Notably, only a minority of respondents were able to correctly identify endemic areas for H. pylori globally, such as South America and Eastern Europe, despite these areas having at least 70% to 80% H. pylori prevalence.26 Importantly, while the overall prevalence of H. pylori in the US is low with some areas having less than 20% prevalence, certain groups have a much higher prevalence, with Blacks and Hispanic/Latinos having as high as 60% prevalence, and some immigrant groups having at least this prevalence and sometimes higher, approaching that of their native country.2,27,28 While a blanket H. pylori “test and treat” strategy for all asymptomatic individuals as a method to prevent GC is not advocated in the US given the overall low prevalence, the current practice guidelines put forth by the American College of Gastroenterology, recommend identifying patients’ additional risk factors for GC, such as family history, while also taking patients’ comorbid illnesses and preferences into consideration.29 Thus, the decision of whether to test and treat for H. pylori in otherwise asymptomatic patients from high prevalence areas should be individualized, but should still be considered. Interestingly, an overwhelming majority of both gastroenterologists and primary care physicians answered that they would recommend against a test and treat strategy for asymptomatic patients from endemic areas for H. pylori and GC. An international working group addressed this important issue almost a decade ago and overall favored testing and eradicating H. pylori in first-degree relatives of patients with GC, as well as in populations with high incidence of “H. pylori-associated diseases,” although recommendations are less clear in the most recent North American GI society guidelines.29 Regardless, while quite reasonable to test and treat high-risk populations, it is apparent that educating providers as to which individuals comprise the “high-risk” populations in the US should be made a priority.

Although the majority of providers were able to identify age, male sex, smoking, H. pylori infection, family history of GC, and smoked/preserved foods as established risk factors for gastric adenocarcinoma, only 22% and 28% correctly identified Blacks and Hispanic/Latinos, respectively, as having higher risk for GC despite the great majority of this physician cohort caring for a patient panel with at least 10% to 30% Blacks and Hispanic/Latinos. First-generation Russians and E. Europeans, as well as Native Americans were also significantly under-recognized as being high-risk despite having as much as five times higher risk of GC compared to lower prevalence areas.3,30,31 Fortunately, 80% to 90% of providers were able to correctly identify Japanese and Koreans as having high risk of GC. Migration data suggests that first-generation immigrants have the same risk as their native country of origin and it takes at least 2 to 3 generations before the risk approaches that of the host country.8,32 Increased recognition of high-risk races/ethnicities and immigrant populations among providers, both primary care and gastroenterologists alike, is a critical first step for addressing the marked disparity in GC prevalence and, similarly, mortality in the US. Importantly, primary care providers often represent the only interaction with the health care field for many patients.

In addition to under-recognition of high-risk populations, there is also considerable variation and lack of certainty with respect to their management. Lack of provider knowledge is likely a strong factor underlying the variable responses, but the dearth of robust data and an insufficient understanding of factors contributing to preneoplastic development and progression (manifested by the lack of clear consensus guidelines for the management of gastric preneoplasia) cannot be overlooked. While the majority of providers were able to correctly identify IM and dysplasia as gastric preneoplastic lesions, only a third were able to correctly identify AG as such. Not surprisingly, the management of IM in a male first-generation Russian immigrant, clearly a high-risk patient, was quite variable, with less than 30% of gastroenterologists and less than 6% of primary care physicians choosing appropriate follow-up management. Indeed, the most common answer for IM management included PPI therapy, which is not appropriate. There are no data to support the use of PPIs for preneoplastic gastric lesions (outside of H. pylori treatment) and some studies suggest that PPIs may actually increase the risk of progression, although a recent Cochrane review concluded that there is at least no strong evidence supporting the risk of long-term PPIs in development of preneoplasia.33–35

To our knowledge, this is the first survey of US-based providers assessing understanding of GC risk factors, particularly with respect to racial/ethnic disparities in prevalence. Despite caring for a multiracial/ethnic patient demographic with high-risk first-generation immigrants, there were significant deficiencies in not only correctly identifying high-risk populations, but also in their management. That such knowledge gaps exist within NYC, one of the most racially and ethnically diverse populations in the US with an equally diverse immigrant population, begs the question of how providers practicing in somewhat less diverse populations would respond to these same questions. In addition to possible lack of generalizability, the present study also has limitations characteristic of any survey-based study, namely inherent response bias. That said, we did have a 3:1 primary care to gastroenterology ratio, which reflected the ratio of e-mail addresses and an approximately 30% response rate. Despite 151 providers, the small size of certain subgroups may have limited the power to detect significant differences.

Based on our findings and according to providers’ preferred learning modality, small-group based lectures and grand rounds/CME style programs are currently being developed to increase GC awareness among health care providers, particularly providers caring for high-risk races/ethnicities and immigrant populations.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported from New York Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (NYSGE) 2016 Florence-Lefcourt Award for Public Outreach (Gastric Cancer).

Author contributions: S.C.S., study concept and design, data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, statistical analysis; manuscript writing; obtained funding; S.H.I., study concept and design, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; study supervision; L.J., study concept and design, statistical analysis, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; study supervision.

Footnotes

See editorial on page 1.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bray F, Ren JS, Masuyer E, Ferlay J. Global estimates of cancer prevalence for 27 sites in the adult population in 2008. Int J Cancer. 2013;132:1133–1145. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choi CE, Sonnenberg A, Turner K, Genta RM. High prevalence of gastric preneoplastic lesions in East Asians and Hispanics in the USA. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:2070–2076. doi: 10.1007/s10620-015-3591-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim Y, Park J, Nam BH, Ki M. Stomach cancer incidence rates among Americans, Asian Americans and Native Asians from 1988 to 2011. Epidemiol Health. 2015;37:e2015006. doi: 10.4178/epih/e2015006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.New York State Cancer Registry. Stomach cancer incidence and mortality by age group, New York State Excl New York City, 2009–2013 [Internet] New York: New York State Cancer Registry; 2016. [cited 2016 Nov 12]. Available from: https://www.health.ny.gov/statistics/cancer/registry/table6/tb6stomachupstate.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program SEER data [Internet] Bethesda: National Cancer Institute; c2016. [cited 2016 Nov 13]. Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee J, Demissie K, Lu SE, Rhoads GG. Cancer incidence among Korean-American immigrants in the United States and native Koreans in South Korea. Cancer Control. 2007;14:78–85. doi: 10.1177/107327480701400111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lui FH, Tuan B, Swenson SL, Wong RJ. Ethnic disparities in gastric cancer incidence and survival in the USA: an updated analysis of 1992–2009 SEER data. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:3027–3034. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3275-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCracken M, Olsen M, Chen MS, Jr, et al. Cancer incidence, mortality, and associated risk factors among Asian Americans of Chinese, Filipino, Vietnamese, Korean, and Japanese ethnicities. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:190–205. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.4.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou HJ, Dan YY, Naidoo N, Li SC, Yeoh KG. A cost-effectiveness analysis evaluating endoscopic surveillance for gastric cancer for populations with low to intermediate risk. PLoS One. 2013;8:e83959. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leung WK, Wu MS, Kakugawa Y, et al. Screening for gastric cancer in Asia: current evidence and practice. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:279–287. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70072-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimizu S, Tada M, Kawai K. Early gastric cancer: its surveillance and natural course. Endoscopy. 1995;27:27–31. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1005628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inoue M, Tsugane S. Epidemiology of gastric cancer in Japan. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81:419–424. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2004.029330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee KJ, Inoue M, Otani T, et al. Gastric cancer screening and subsequent risk of gastric cancer: a large-scale population-based cohort study, with a 13-year follow-up in Japan. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:2315–2321. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jun JK, Choi KS, Lee HY, et al. Effectiveness of the Korean National Cancer Screening Program in reducing gastric cancer mortality. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1319–1328.e7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fock KM, Talley N, Moayyedi P, et al. Asia-Pacific consensus guidelines on gastric cancer prevention. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:351–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.ASGE Standards of Practice Committee. Wang A, Shaukat A, et al. Race and ethnicity considerations in GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:593–599. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sipponen P, Kimura K. Intestinal metaplasia, atrophic gastritis and stomach cancer: trends over time. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1994;6(Suppl 1):S79–S83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuipers EJ, Uyterlinde AM, Peña AS, et al. Long-term sequelae of Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Lancet. 1995;345:1525–1528. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)91084-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.You WC, Zhang L, Gail MH, et al. Gastric dysplasia and gastric cancer: Helicobacter pylori, serum vitamin C, and other risk factors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1607–1612. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.19.1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Correa P, Piazuelo MB. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric adenocarcinoma. US Gastroenterol Hepatol Rev. 2011;7:59–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parkin DM. The global health burden of infection-associated cancers in the year 2002. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:3030–3044. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Plummer M, de Martel C, Vignat J, Ferlay J, Bray F, Franceschi S. Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2012: a synthetic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4:e609–e616. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30143-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramirez-Ramos A, Gilman RH, Leon-Barua R, et al. Rapid recurrence of Helicobacter pylori infection in Peruvian patients after successful eradication. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:1027–1031. doi: 10.1086/516083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.ASGE Standards of Practice Committee. Evans JA, Chandrasekhara V, et al. The role of endoscopy in the management of premalignant and malignant conditions of the stomach. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.03.1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Correa P, Piazuelo MB, Wilson KT. Pathology of gastric intestinal metaplasia: clinical implications. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:493–498. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peleteiro B, Bastos A, Ferro A, Lunet N. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection worldwide: a systematic review of studies with national coverage. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:1698–1709. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3063-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malaty HM, Evans DG, Evans DJ, Jr, Graham DY. Helicobacter pylori in Hispanics: comparison with blacks and whites of similar age and socioeconomic class. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:813–816. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90011-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fennerty MB, Emerson JC, Sampliner RE, McGee DL, Hixson LJ, Garewal HS. Gastric intestinal metaplasia in ethnic groups in the southwestern United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1992;1:293–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chey WD, Leontiadis GI, Howden CW, Moss SF. ACG clinical guideline: treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:212–239. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Espey DK, Wu XC, Swan J, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2004, featuring cancer in American Indians and Alaska Natives. Cancer. 2007;110:2119–2152. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bertuccio P, Chatenoud L, Levi F, et al. Recent patterns in gastric cancer: a global overview. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:666–673. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maskarinec G, Noh JJ. The effect of migration on cancer incidence among Japanese in Hawaii. Ethn Dis. 2004;14:431–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Song H, Zhu J, Lu D. Long-term proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use and the development of gastric pre-malignant lesions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(12):CD010623. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010623.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fox JG, Kuipers EJ. Long-term proton pump inhibitor administration, H pylori and gastric cancer: lessons from the gerbil. Gut. 2011;60:567–568. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.229286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klinkenberg-Knol EC, Nelis F, Dent J, et al. Long-term omeprazole treatment in resistant gastroesophageal reflux disease: efficacy, safety, and influence on gastric mucosa. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:661–669. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(00)70135-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.