Abstract

The Syrian crisis is considered the ‘world’s single largest crisis for almost a quarter of a century that has the biggest refugee population from a single conflict in a generation’ (UN High Commissioner for Refugees, 2016). The rapid adoption of Facebook among Syrians questions whether it helps in maintaining the social capital of a war-torn nation and a dispersed Syrian population worldwide. Data was collected by means of a Facebook survey from 964 Syrian users. Results indicated that Facebook enhanced social identity and social capital through facilitating communication, collaboration and resource sharing among dispersed Syrians inside and outside the country. However, the offline rift of the nation was extended to Facebook through promoting hate speech among opposed parties. Results of this study may advance the understanding of the role of Facebook on social capital in countries going through similar crisis situations.

Keywords: Sociology, Information science

1. Introduction

The severe political conflict in Syria affected its social capital within the escalation of the crisis for six years resulting in the largest worldwide dispersion of a nation in history. According to António Guterres, UN High Commissioner for Refugees; ‘this is the biggest refugee population from a single conflict in a generation. It is a population that needs the support of the world’ (UNHCR, 2016).

The internet has enabled individuals to stay in contact with geographically distant social ties through a variety of technological tools (Cheung et al., 2015), thus, aiding social communication and strengthening social bonds (DeKerckhove, 1997). Researchers questioned whether different types of internet use had different effects on people with different social resources (Bessière et al., 2008). In disaster situations, such as Hurricane Katrina, internet users in New Orleans made use of the diverse weak ties people formed online as an important resource for informational support (Procopio and Procopio, 2007). Past studies found a positive association between social capital and positive outcomes such as effective governance (Furlong et al., 1994), economic growth and development (Woolcock, 2002), education (Coleman, 1988), and physical health (Lomas, 1998). Social Media in the Arab world comprises a critical part of everyday life to an extent that Arab users regard Social Media as a ‘life enhancer’ (Arab social media report, 2011). Connectivity in general is the main reason for people in the Arab world to use Social Media followed by gaining information (55%; 12%). Facebook has become one of the leading Social networking sites (Facebook, 2016). Youth between the ages of 15 and 29 make up 75% of Facebook users in the Arab region. Gender breakdown of Facebook users indicates an average 2:1 ratio of male to female users in the Arab region, compared to almost 1:1 globally (Arab social media report, 2011). In Syria, Facebook was rated among the top used social media channels reaching to 97%. Preferences for Facebook usage among Syrians is 47%. The vast majority (83%) of current Facebook Syrian subscribers access the channel on daily basis. Facebook app usage is the highest in Syria (95%) among Arab countries. Studies found that the impact of Social Media across all the Arab regions has a role in improving communications among people, and expands on knowledge and education, in addition to receiving instantaneous updates (Arab Social Media Report, 2015). However, the social value of Facebook may differ among people from different cultures, and within social capital (Lin, 1999; Putnam, 1995). The rapid adoption of Facebook questions whether it impacts social capital formation and social relationships (Subrahmanyam et al., 2008), and indicates a need for research on the role of Facebook on people’s lives (Mazman and Usluel, 2010). Many studies explored the social influence of computer-mediated communication (e.g.) but few have explored its role in building social capital during crisis situations.

There is dearth of research examining the development of relationship ties online. To date there is scarce research studies on the social networking use of Syrian refugees living worldwide, and little is known about the composition of social networks acquired through Facebook. Thus, it becomes critical to research the network characteristics and its potential benefits of maintaining the social capital of a dispersed Syrian population worldwide.

The status of participants are beyond the scope of the study. This paper will use the concept of Syrian social capital to refer to all Syrian persons living inside and outside the country. Thus, the term refugees in this paper refers to: (1) displaced Syrians inside the country; (2) displaced Syrians outside the country that registered as refugees at the new destination; and (3) displaced Syrians outside the country who started a new life and business in the new country, but not as refugees (4) Syrian immigrants from before the crisis who have relatives and friends in Syria.

This paper argues that the use of Facebook for social relations purposes will lead to bridging and bonding Syrian social capital through the different characteristics that Facebook offers. Thus, the main purpose of this study is to examine how Facebook influences the maintenance of Syrian social capital during its crisis. Results of this study may advance the understanding of the role of Facebook in bridging and bonding social capital in countries going through similar crisis situations.

2. Background

The Syrian Arab Republic, also known as Syria, is located in Western Asia. It borders Lebanon and the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to the north, Iraq to the east, Jordan to the south, and Palestine to the southwest. The Syrian crisis is now considered as the “world’s single largest refugee crisis for almost a quarter of a century under UNHCR’s mandate”. As of June 20th 2016, the number of Syrian refugees reached five million worldwide. The UN Refugee Agency, and UNHCR announced in GENEVA,– “Despite rough seas and harsh winter weather, more than 80,000 refugees and migrants arrived in Europe by boat during the first six weeks of 2016, more than in the first four months of 2015” (UNHCR, 2017). Tragically, and with no end in sight to Syria’s war, now in its sixth’s year, the crisis is escalating dramatically and the number of refugees are rising. The number of refugees fleeing the conflict in Syria has passed four million. At current rates, UNHCR expects the figure to reach around 4.27 million by the end of 2015. The total number of Syrian refugees in neighboring countries reached more than 4,013,000 people. The figure of four million comprises 1,805,255 Syrian refugees in Turkey, 249,726 in Iraq, 629,128 in Jordan, 132,375 in Egypt, 1,172,753 in Lebanon, and 24,055 elsewhere in North Africa. Not included, are more than 270,000 asylum applications by Syrians in Europe, and thousands of others resettled from the region elsewhere, within several calls to settle Syrian refugees in Europe and in the United States (Chakraborty, 2015; Tausch, 2015). In addition 7.6 million people are displaced inside Syria (UNHCR, 2016). However, the impact of the Syrian armed conflict was not the same across the entire country. Raqqa was among the governorates that were most affected by war and hostilities, followed by Idlib, Hasakah, and Deir ez-Zor, and Aleppo each of which has been subjected to large-scale displacement and military operations, thus, have negatively affected the social fabric in their regions causing severe degradation in social relations. On the other hand, the impact was the lowest in Tartus, Sweida, Lattakia and Damascus, since these regions were less exposed to destruction (Social watch, 2017).

3. Theory

Social capital has been cited in a wide range of disciplines (Bögenhold, 2015). It is used in multiple fields with a variety of definitions, and is generally perceived positively (Adler and Kwon, 2002). It refers to a ‘network ties of goodwill, mutual support, shared language, shared norms, social trust, and a sense of mutual obligation that people can derive value from. It is understood as the glue that holds together social aggregates such as networks of personal relationships, communities, regions, or even whole nations’ (Huysman and Wulf, 2004). Thus, social capital is the accumulated relationships between people (Coleman, 1988). For an individual, social capital helps drawing on resources from other members of the same network in the form of information, personal relationships, employment opportunities, and the ability to organize groups, in addition to leveraging personal connections from multiple sources (Paxton, 1999). Social capital has been conceptualized at the individual level, at the relational level and at the community level (Lin, 1999). There are two important constructs in the literature regarding social capital in social network research (1) Bonding social capital links people based on consciousness of common identity (e.g., family members, close friends and those who share the same culture or ethnicity), and are tied through strong personal connections enabling them to provide each other with emotional support, thus, it reflects the quality side of relationships, and; (2) Bridging social capital which links people beyond their awareness of identity (e.g., distant friends and colleagues), it is appropriate for information diffusion and for linking individuals to external resources, rather than for providing emotional support, thus, it reflects the quantity side of relationships (Putnam, 2000). Directed communication can improve users’ bonding and bridging social capital through the content and strength of the relationship (e.g., one-on-one messaging strengthen relationships through expressed supportiveness and self-disclosure resulting in increased trust and engagement) (Oswald et al., 2004). Thus, due to its nature, directed communication should be useful for maintaining existing relationships, and for supporting the growth of new ties. Social networks change over time as relationships are formed or abandoned. Significant changes in Syrian social networks has occurred after individuals moved from geographic locations in which their network was originally formed to other locations.

Research suggests several possible motives for the use of Social Network Sites (SNSs). According to the uses and gratification theory by Katz et al. (1973), individuals use media resources to their own benefit. They tend to actively seek out a specific media which is unique in its purpose and content in order to achieve certain results or gratifications that satisfy their personal needs. It acknowledges that viewers are goal oriented, thus, they seek to accomplish their goals through a specific chosen media source. Moreover, individuals have several needs, therefore they create a range of alternatives to choose from, in order to satisfy those needs. While being aware of their motives and choices, they become aware of the consequences of their involvement in the media source as a whole. It proposes that media users are best understood within an individual’s motive for using a medium (Katz et al., 1973). It is regarded as a functional tool that individuals use to satisfy a certain pre-set goal (Hollenbaugh and Ferris, 2014). Facebook use adoption motivation is reflected in its Perceived Usefulness (PU). This construct was originally developed by Davis (1989) in the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) as an extension to the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) by Fishbein and Ajzen (1975). It measures the level an individual regards a given technology enhances personal fulfilment (Davis, 1989). It is regarded as a motivational factor for using technologies. There is consensus in the literature that social capital reflects the many benefits people get from their social relationships (Lin, 1999). Lin (1999) emphasizes the importance of social relations in social capital formulation referred to as ‘investments in social relations with expected returns’ (p.30). Facebook helps people maintain existing relationships as well as creating new ones (Ellison et al., 2014). According to Mazman and Usluel (2010), ‘social relations make up an important dimension of Facebook and may include making new friends, maintaining existing ones and communicating. These social groups include neighbors, family members, groups and other people who share common interests’. Mazman and Usluel (2010) propose that individuals adopt Facebook usage when they perceive its usefulness which in turn affects their use purpose for social relations (e.g., making new friends and maintaining old and existing relations with neighbors, family, and others with similar interests) (Mazman and Usluel, 2010). Thus, based on the above it is proposed that:

H1: Perceived Usefulness of Facebook will influence its usage for social relations, communicating, collaborating, resource sharing, maintained Syrian social capital and identity.

Social Networking Sites (SNS) are designed to link people with friends, family, and other strong ties, as well as other acquaintances, and to develop new ties. SNS are platforms of huge user base that facilitate diverse activities including playing games, joining groups, photo sharing, news broadcasting, and message exchange. Online communities enhance social networks and improve individuals’ relationships (Wellman et al., 2001). Social networking sites offer a social dimension to its users that other information systems and online applications cannot offer which is manifested in social capital (Ellison et al., 2011). Facebook as a SNS defined is ‘a social utility that helps people share information and communicate more efficiently with their friends, family and coworkers’ (Facebook, 2016). It is an online arena for presenting ideas, communicating, interacting, and making social connections. Most Facebook users draw resources and information from online relationships and networks (Ellison et al., 2006), thus, allowing people to extend their offline world to the online world. However, Facebook use may vary significantly among people from different cultures (Stefanone and Jang, 2007).

Facebook as a SNS is primarily used for social purposes (Mazman and Usluel, 2010). Facebook behavior includes undirected communications reflected in the News Feed feature on Facebook containing general broadcasts, and is similar to small talk off line which is the base for developing old and new relationships between friends (Knapp and Vangeslisti, 2003), (e.g., interactions with friends’ friends, status updates, photo albums, and links). It consists of undifferentiated exposure to social news (e.g., reading others’ updates), and broadcasting (e.g., writing without targeting a particular other). Undirected communications are likely to enhance relationships’ growth and maintenance through the profile information and status updates that provide grounds for users’ similarities (Hancock et al., 2008). In contrast, directed communications include interacting with friends through activities such as messaging, wall posts, and chats. The like feature on Facebook allows for commenting and photo tagging leading to a meaningful relationship between individuals. The social relations utilities offered by Facebook for connectivity and social support, content creation, sharing, knowledge elaboration and information aggregation (Lee and McLoughlin, 2008) affect the social usage of Facebook for communication, collaboration and resource/material sharing (Mazman and Usluel, 2010).

H2: The need for social relations will influence the usage of Facebook for communicating, collaborating, resource sharing, maintained Syrian social capital and identity.

Facebook use among individuals was found to help in bridging social capital (Ellison et al., 2007; Steinfield et al., 2008; Valenzuela et al., 2009) where disconnected social groups can efficiently maintain contact with friends and distant networks of geographically and socially dispersed acquaintances (Díaz Andrade and Doolin, 2016). For example, the armed conflict in Syria had a catastrophic social impact on social relations where displacements and involvement in violent acts had negative effects on bridging Syrian social capital (Social watch, 2017). “Zuckerberg’s solution to the decline in what he calls ‘social infrastructure’ and Putnam calls “social capital” is: more Facebook. Specifically, more Facebook groups”. Zuckerberg said: “If we can do this, it will not only turn around the decline in community membership we’ve seen for decades, it will start to strengthen our social fabric and bring the world closer together” (The guardian, 2017). Several studies have shown that the use of Facebook is associated with greater quality of individuals’ social relationships with their home country (Damian and Van Ingen, 2014; Lee et al., 2016), and especially for maintaining existing relationships with family and friends (Damian and Van Ingen, 2014). Studies found a relationship between the use of SNS and perceived social capital where individuals gain greater access to informational, emotional, and tangible support through participating in SNS, which can either be a base for formulating bridging or bonding social capital (Burke et al., 2010). Social networking sites (SNS) affect social outcomes through bonding and bridging existing ties and acquaintances (Ellison et al., 2007; Valenzuela et al., 2009). It can also be used effectively for communication during crisis situations (Eriksson, 2015; Zeng et al., 2016). The advantages of bridging social capital includes cultural exposure and feeling part of a larger community (Putnam, 1995; Donath and Boyd, 2004). Expressive information sharing is related to better bridging social capital (Papacharissi, 2015). In a study by Díaz Andrade and Doolin (2016), they concluded that the use of technology as a resource enables refugees to be socially connected, to effectively communicate, and to be able to express individuals’ cultural identity. Complementing these findings, Social Media applications, through facilitating connections of refugees with family and friends results in them feeling being at home (Wilding and Gifford, 2013).

H3: Communicating, collaborating and resource sharing activities on Facebook will influence the bonding of Syrian social capital.

H4: Communicating, collaborating and resource sharing activities on Facebook will influence the bridging of Syrian social capital.

The social identity theory (SIT) states that groups are formed based on peoples’ categorization of membership (Tajfel, 1978). The social identity construct is defined as ‘the part of an individual’s self-concept which derives from his knowledge of his membership of a social group (or groups) together with the emotional significance attached to that membership’ (Tajfel, 1978). It has been categorized in research according to two components that reflect three dimensions (1) the cognitive component comprises categorization which reflects how much an individual feels part of a group, and (2) the affective component which comprises the sense of belonging and the attitudes towards the in-group that reflects how committed an individual is to the group. The social identity construct has been recognized in research as vital for understanding inter-group relations (Feitosa et al., 2012b; Sohrabi et al., 2011). It has proved to be important in overlapping fields of diversity, identities, and cross- cultural work psychology (Feitosa et al., 2012a; Feitosa et al., 2012b; Ferdman and Sagiv, 2012). The basis for in-group and outgroup formulation is that individuals like to interact more with similar others because they can be more predictable (Brewer, 2002; Gerard and Hoyt, 1974). Individuals form positive evaluations and are more attached to those who share with them similar attributes (Feitosa et al., 2012a; Feitosa et al., 2012b) where they can be identified with a certain group according to categorization (e.g., religion, ethnicity, etc.). Social identification with a certain group provides comfort to a fellow group member (e.g., through collaboration and information sharing) (Levine and Moreland, 1998). Social identities are regarded as the mechanism for effective social networks (Clopton and Finch, 2010). There is a need for more research on the social identity construct for a better understanding of its cultural role and its operationalization (Feitosa et al., 2012a; Feitosa et al., 2012b). According to Hofstede (1991), identity surfaces differently across cultures, which in turn shapes the differences in behaviors across social contexts (Hopkins and Reicher, 2011). Moreover, Facebook provides beneficial tools with which people enhance their social relations which helps in communicating one’s identity to others (Wilson et al., 2012).

H5: Communication, collaboration and resource sharing on Facebook will significantly influence Syrian social identity. However, not all SNS have the same social effect (Burke et al., 2010). In addition, although social capital has many benefits, research documented several negative characteristics related to it (Graeff and Svendsen, 2012). Social capital can be conceived in negative terms when non-group members are not allowed access to the same benefits as members based on beliefs, religion or ethnic backgrounds (Helliwell and Putnam, 2004) leading to creating and promoting hate groups and hate speech (Pepper et al., 2012; Recuero et al., 2011). Facebook groups – like any social capital – can just as easily be used for ill as for good, and social capital is not always an unalloyed good. For example, the dense networks of social organizations and clubs in Germany helped promote the spread of Nazism. And even a cursory search of Facebook unearths networks of extremists using groups to recruit and organize (Satyanath et al., 2013). Moreover, in the wake of the Charlottesville attacks that incited violence, communities were condoning and encouraging violence to an extent that some wrote poems about killing (Engadget, 2017). Similarly, there are more than seventeen-designated hate groups on Facebook pages or groups running Facebook’s commenting service that have not been dropped from Facebook due to that according to Facebook standards, “To remove an entire group for being a hate group, we must find that the group is dedicated to promoting hatred against a protected category” of people (Fast company, 2017). Till date, Facebook has struggled on how to handle hate groups on its platform. It has taken down at least eight pages that had been active in promoting violence (CNNtech, 2017), due to that Facebook prohibits “hate speech.” However, according to Facebook there is no universally accepted definition of hate speech. Facebook defines the term to mean “direct and serious attacks on any protected category of people based on their race, ethnicity, national origin, religion, sex, gender, sexual orientation, disability or disease” (Facebook, 2017). Facebook tends to remove hate speech quickly, however there are instances of offensive content that are not considered as hate speech according to Facebook’s definition (Facebook, 2017).

3.1. Model

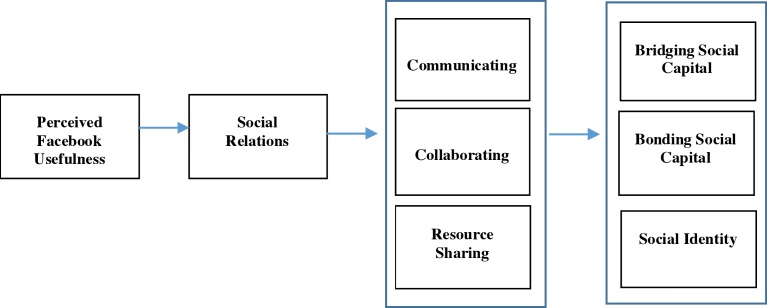

In this study, the proposed study model consists of eight constructs that were adapted after completing a literature review on existing theories on the use Facebook and social capital in relation to its usefulness for building social relations and enhancing social identity through communication, collaboration and resource sharing. Social capital is explored based on two constructs; bridging and bonding social capital as shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Research model.

4. Methods

Approval for conducting this study was obtained from Damascus University, in addition, consent from the participants in the interviews was obtained prior to conducting the interviews. This paper followed a quantitative and a qualitative mixed-method approach for the aim of gaining a better understanding of the research problem and for improving validation through the triangulation of results from both methods (Creswell, 2008).

4.1. Qualitative study

A qualitative study comprised of 15 participants were randomly selected from the area of Damascus who agreed to participate on voluntary basis for conducting face-to-face interviews. Seven interviewees were male, and eight were female. Their ages differed: three were between 18–25 years old; four 26–32 years old; five 33–45 years old; and three interviewees were above 46. Six participants in the sample have high school certificates, and nine have a university degree. Ten of the interviewees have been displaced within Syria, whereas, five did not leave their homes. However, all participants had family members/and or friends that were either displaced inside or outside the country, at the time of the study. Five interviewees lived in rented apartments and five were living in shelters. All interviews were conducted following a semi-structured approach, using open-ended questions that allowed for open ended responses. Participants were asked questions related to parting from relatives and friends, how they have been using Facebook to connect with them, and their perceptions of the use of Facebook in particular, for social relations, and for bonding and bridging with friends and family members during the Syrian crisis. Each interview lasted 30 min on average. Interviews were conducted in Arabic. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. Next, using the constant comparison method, data was organized and coded (Corbin and Strauss, 2015). A preliminary codebook was created and refined using an iterative process. Codes were elicited and merged into categories. Specifically, themes that reflected the use of Facebook and its perceived usefulness in maintaining and building social relations through communicating, collaborating, and the sharing of information. In addition, in which way they affected bonding, bridging and maintained their social identity with other displaced Syrian friends and family members.

Results of the qualitative data analysis revealed several important implications for Syrians’ use of Facebook during the crisis. First, Facebook had a strong impact on maintaining social relationships, and consequently on the bridging and bonding with physically disconnected friends and family members (e.g., because participants perceived Facebook useful for maintaining their social relations with those that they were physically disconnected with, they used Facebook to share news, collaborate, and to communicate with other fellow Syrians, thus, leading to better Syrian bridging and bonding with those inside and outside the country, which in turn, enhanced their feelings of their social identity). Thus, it enhanced their social relationships through mass communication, collaboration, sharing, and information dissemination, which in turn, positively affected Syrians to bond, and bridge with similar dispersed others worldwide.

Participants were asked whether their use of Facebook for collaboration and information search made them perceive Facebook as more useful, or whether their perceptions of Facebook’s usefulness, made them more likely to use it. Interviewees acknowledged that perceptions of Facebook usefulness among Syrians, as a tool for collaborating and communicating with their social ties, motivated them and motivated other non-Facebook users, to join the platform, during the crisis. In fact, all interviewees stated that many of their family members and friends, especially the elders, started a Facebook account during the Syrian crisis in order to communicate with their children and displaced relatives inside and outside the country, this is also evident in the number of Facebook users in Syria that potentially increased from June 2010 until June 2012, during the Syrian conflict (Arab Social Media Report, 2015):

“my mother started a Facebook account just to be able to relate with my sister who fled to Sweden with her family”.

“I know a lot of friends and family members who didn’t use Facebook before the crisis….they became very active on daily basis during the crisis”.

“landlines are extremely expensive… if they were functioning… therefore, Facebook is my first choice for communicating with my friends and family members because its free and is 24/7 available”.

Interviewees made the correlation between the use of Facebook for maintaining social relationships, through the exchange of information, videos, news updates, eliciting discussions using the Arabic language, and with enhanced bonding and bridging with other Syrian persons:

“whenever I want to find news about my friends who left the country, or governorate…., I use Facebook to bond and stay connected with them”.

“it’s so cool to be able to interact in Arabic using a foreign medium…my English is very weak… all those on my contact list are also weak in English”.

“through Facebook I can bond with many of my friends and family members inside and outside Syria of whom I lost physical touch with during the Syrian crisis”.

“Facebook groups are very useful for maintaining social relationships through networking … it gives me the feeling that I haven’t parted with my friends and family although we are so distanced”.

“I would check a Facebook group I trust; ‘yawmeiat kazifet hawn’, every morning for updates on random bomb shelling before making a decision to leave my house”.

“I used to think that Facebook is a waste of time…. but during the crisis, when I couldn’t hang out with my friends and relatives for safety reasons, I used Facebook to relate with my loved ones”.

“Through Facebook, I managed to help advice many of my friends and family members who faced problems, especially those that I could not get physically in touch with”.

“My sister who fled to Germany with her children and husband found moral support through connecting with my mom on Facebook, and with the rest of our family….it helps her overcome feelings of loneliness”.

However, social relations became weaker for some individuals, or were totally cut off, especially with targeted Syrian persons (e.g., Syrians who had opposing opinions on Facebook, were divided into distinct groups, or individuals accordingly. They developed hate speech between them, reaching in some instances to performing hate actions such as blocking or deleting or reporting abuse a close friend or even a family member). Thus, although Facebook was perceived as a useful medium that facilitated the bonding and bridging of Syrian social capital and enhanced social relations, it had somehow a negative impact on the Syrian social capital through dividing Syrians according to their beliefs:

“I know many people, including I … unfriended others on Facebook because they didn’t approve of what others’ posted regarding the Syrian crisis”.

“I didn’t know that some of my friends and family members had opposing convictions…so I deleted them from my contact list”.

“If I don’t perform a ‘Like’ on Facebook to what a friend of mine or a member of my family posts, I will certainly be blocked”.

“my uncle who fled to Denmark, does not communicate with us anymore because of our opposing opinions on Facebook”.

“I can choose whom I want to stay friends with, and whom I would like to cut of my life after reading their posts on Facebook”.

To conclude, all interviewees perceived Facebook as an extraordinary platform for building social relations and for bridging and bonding with family and friends, thus, enhanced perceptions of common Syrian social identity regardless of distances. On the other hand, Facebook, used as a platform, led to categorizing the Syrian population into three distinct well-known groups online; (1) Syrian persons who are with, opposed to (2) Syrian persons who are against, and (3) Syrian persons who do not express their opinions publically, known as “ al ramadeein” or the greys. Thus, as a result, Facebook enhanced the bonding and bridging between both the first and second group, and the second and third group. But on the other hand, it weakened the social ties between the first and second group, including some persons in the third group, out of fear of being related to either one of the opposing groups.

4.2. Quantitative study

4.2.1. Instrument

Technology usage and adoption theories were reviewed to expand Facebook usage. Perceived social capital bridging and bonding constructs were measured by adapting existing internet-specific social capital scales to Facebook usage (Ellison et al., 2007; Johnston et al., 2013). The social identity construct used for the purpose of this study comprised two questions that reflect the categorization and the sense of belonging components. The cognitive aspect of the construct was adapted from Hobman and Bordia (2006), it measures one’s awareness of in-group membership ‘using Facebook I can join Syrian groups that have the same interests where I see myself as a member of the group’, and the affective aspect of the construct was adapted from Evans and Jarvis (1980), it measures the sense of belonging to a group ‘Facebook allows for the creation of groups who feel involved in what is being shared of same interests and needs’. The attitudes towards the in-group was not included as attitudes need some time to form and some people could have joined the Facebook group recently. The perceived usefulness construct was adapted from the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) by Davis (1989). The Communication, Collaboration, Resource/Material Sharing, Social Relations items were adapted from Mazman and Usluel (2010). All items from existing measures were modified to fit the study context. First, English items from the scales were translated to Arabic, then back translated to check the translation’s validity (Brislin, 1986). Next, for validation of the questionnaire, and to check for consistency in meaning and in the clarity and understandability of all scale items, expert opinion was attained. Based from the feedback received from the experts, the scale was further modified. The measurement items were formulated as Likert-type statements anchored by a five-point scale ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”). A pilot test was conducted on the questionnaire before its final administration online.

4.2.2. Participants and data collection

The population of the study comprises all Syrian persons living inside and outside Syria who are actual Facebook users. The information required for this study was not available in the form of secondary data, thus, primary data was collected through a survey using a standardized online questionnaire designed in Qualtrics. All participants were required to have Facebook accounts and participation in the survey was on voluntary basis. To increase the response rate of participants, survey messages were placed on Facebook, and invitations were posted for the survey on thirty five popular Syrian forums and groups Table 1., in addition to other private Syrian groups, and personal accounts. Then a snowball technique was used among participants who volunteered to ask their friends and family members to post the link on their wall and voluntarily forwarded the survey’s link to other families and friends. The snowball sampling technique was chosen because it is useful for identifying participants that are hard to locate and for meeting unusual criteria (Lewis-Beck et al., 2011) such as war contexts. However, to ensure non-sample bias, the 35 Syrian Facebook groups were randomly identified at the beginning of the study in order to draw from them a random sample that represents the Syrian community from different geographic areas and from diverse social, educational and political backgrounds as depicted in Table 1. To encourage participation, the snowball technique was chosen due to that Syrians, as a result of the crisis, did not trust participating in activities they are not aware of its purpose, out of fear of being abused. This is evident in a study that found that the crisis minimized reciprocal trust among Syrians by 31% (Social watch, 2017). Therefore, this technique assured participants the trust dimension from the Facebook groups’ they are members of.

Table 1.

Distribution of questionnaire on Facebook groups (including the snowball technique).

| 1. | Syrian gatherings |

| 2. | Syrians and Jordanians for life |

| 3. | Syrians in Turkey, Lebanon and Saudi Arabia |

| 4. | Syrian Research Students in Social Sciences |

| 5. | The biggest grouping of Damascus University students |

| 6. | Work in France for Syrians |

| 7. | Third year students at the Faculty of Economics at Damascus University |

| 8. | Syrian students in Egypt |

| 9. | The Syrian house in Germany |

| 10. | Discussions between Syrian students |

| 11. | From Britain, here is Syria |

| 12. | Syrians In Birmingham |

| 13. | Accompagnateurs des réfugiés syriens |

| 14. | Syrier i Sverige |

| 15. | Syrian in Germany_ Syrer in Deutschland |

| 16. | Higher studies students at Damascus University |

| 17. | Professors and student groups at the Faculty of Economics- Damascus University |

| 18. | Higher Studies students at the Faculty of Economics |

| 19. | Syrians in the USA |

| 20. | Syrians in UK |

| 21. | Syrian youth in Manchester |

| 22. | Syrians In Glasgow |

| 23. | Syrians in Australia |

| 24. | Syrian house in Britain |

| 25. | The English Club for Syrians in the UK |

| 26. | The Syrian political club in Britain |

| 27. | Syrian courses for students |

| 28. | Newly arrived Syrians to Britain |

| 29. | The Syrian community in Britain |

| 30. | Free announcements for Syrians in Britain |

| 31. | Revolutionaries of London |

| 3 | Free Syrian community in Britain |

| 33. | SCinB – Syrian Community in Britain |

| 34. | The Syrian British family club |

| 35. | London Syrian Cycling Club |

In addition, the link of the survey was distributed using WhatsApp via smart phones where participants can log on to the Facebook link and take the survey. The same above mentioned snowball technique was used for the smart phones. The IP address of each participant was kept recorded to prevent multiple logging.

At the end of the data collection period which lasted for two months, 964 usable responses were received. Sample characteristics are in Table 2.

Table 2.

Sample characteristics.

| Gender | Sample | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 573 | 40.6 |

| Female | 391 | 59.4 |

| Total | 964 | 100.0 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 18 and under | 33 | 3.4 |

| 19–30 | 652 | 67.4 |

| 31–45 | 222 | 23.0 |

| 46 and over | 57 | 5.9 |

| Total | 964 | 100.0 |

5. Analysis

To verify the measurement scales, various forms of reliability, validity, exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis were applied. Structural equation modeling (SEM) using AMOS 20.0 software was further applied to explore for study hypotheses.

First, using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), an Exploratory Factor Analysis was conducted at the first level of analysis for the aim of selecting the number of factors, and for assessing variation in order to identify common factors, and to determine how many factors should be retained and what their communalities are (Everitt and Howell, 2006) in order to determine unique variance among items and to meet the criteria of reliability and validity.

Maximum Likehood with promax rotation was chosen for the scale items as it provides a goodness of fit test for the factor solution and it is superior to other estimation techniques (Kelloway, 1998). In addition, AMOS uses Maximum Likehood by default in structural equation modeling. The non-constrained factor solution was chosen with eigenvalues greater than three. Results indicated a five-factor solution. The KMO and Bartlett’s test for sampling adequacy was highly significant 0.937 and the communalities for each variable were sufficiently high (all above 0.500), thus indicating that the variables were adequately correlated for a factor analysis. The first factor consisted of items from the Communicating and the Resource Sharing/collaborating – scales, three items (6, 7, and 9) from the Bridging scale, and one item (15) from the social relations scale. After examination, the loaded items were found to reflect meaning related to communicating, connectedness, interaction, and news updates, therefore they were re-named as the Collaborating, Sharing News & Communicating (COSNCM) construct. The second factor comprised of three items from the Social Bonding scale (11, 12, and 13) and one item (19) from the Social Identity scale thus, creating a new construct; the Social Identity Bonding (SIBND) construct. The Perceived Usefulness construct (PU) consisted of its original items and an additional item (10) from the Bonding scale that reflects use benefits regardless of distances (It is easy for me to know what is going on with my other Syrian friends Facebook regardless of distances between us). The forth construct comprised two items (5 and 8) from the Social Bridging scale and one item (25) from the Collaborating scale, thus, creating a new construct; the Collaborative Bridging (CLBRG) construct. The fifth construct comprised of one item from the Social Relations scale (14) and one item from the Perceived Usefulness scale (1) which reflects in its meaning the ability of socializing with many people at the same time (Facebook allows me to communicate with a large number of Syrians in a short time period) creating a new construct; the Social Relations (SR) construct.

The five factors demonstrated sufficient convergent validity as their loadings were all above the recommended minimum threshold of 0.350 (Hair et al., 1995). The factors also demonstrated sufficient discriminant validity, as the correlation matrix demonstrates no correlation above 0.700, and there were no problematic cross-loadings. All coefficient alphas exceed the recommended threshold of .7, indicating there is a reliability for each factor. Scale constructs and measurement items along with Cronbach’s Alphas are Table 3.

Table 3.

Factor loadings, Average variance explained & Cronbach Alpha.

| Item | Factor loadings EFA | Average variance explained | Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collaborating, Sharing News & Communicating (COSNCM) | 29.819 | 0.868 | |

| 23. I use Facebook to share issues with other Syrians since many people I know use it. | .732 | ||

| 21. Facebook allows to share rich multimedia resources and media between Syrians. | .730 | ||

| 22. Facebook facilitates the sharing of a wide variety of resources between Syrians. | .706 | ||

| 15. I use Facebook to find new Syrian friends. | .661 | ||

| 17. The use of Facebook improves discussion between Syrians. | .654 | ||

| 24. Facebook provides resources to support Syrians in their daily needs during Syrian crisis. | .604 | ||

| 16. The use of Facebook improves communication between Syrian families regardless of distances. | .537 | ||

| 6. I feel connected with my country through interacting with Syrians on Facebook beyond distances. | .426 | ||

| 9. I use Facebook to communicate with my friends during Syrian crisis. | .416 | ||

| 18. The use of Facebook improves the delivery of news and updates to all Syrians. | .341 | ||

| 7. It is easy for me to know what is going on in Syria through other Syrians on Facebook. | .301 | ||

| Social Identity Bonding (SIBND) | 34.042 | 0.781 | |

| 19. Using Facebook I can join Syrian groups that have the same interests where I see myself as a member of the group. | .748 | ||

| 20. Facebook allows for the creation of groups who feel involved in what is being shared of same interests and needs. | .691 | ||

| 11. There are several Syrian friends and groups on Facebook that I trust to help me solve my problems. | .619 | ||

| 12. There is a Syrian (friend or family) on Facebook from Syria I can turn to for advice about making important decisions. | .539 | ||

| 13. When I feel lonely, there are several Syrian people on Facebook I can talk to. | .332 | ||

| Perceived Usefulness (PU) | 37.009 | 0.839 | |

| 3. In general, the use of Facebook improves my personal relationships with other Syrians. | .645 | ||

| 4. Facebook makes it easier to establish and maintain personal relationships. | .576 | ||

| 2. Facebook helps me to maintain my old personal relationships. | .455 | ||

| 10. It is easy for me to know what is going on with my other Syrian friends Facebook regardless of distances between us. | .372 | ||

| Collaborative Bridging (CLBRG) | 39.185 | 0.880 | |

| 25. I use Facebook to collaborate with other Syrians on what is new. | .709 | ||

| 8. Facebook makes me feel that all Syrians in the world are connected. | .437 | ||

| 5. Interacting with other Syrians on Facebook makes me feel part of a larger Syrian community. | .336 | ||

| Social Relations (SR) | 41.083 | 0.860 | |

| 14. I use Facebook to locate Syrian friends I lost touch with for a while because of Syrian crisis. | .648 | ||

| 1. Facebook allows me to communicate with a large number of Syrians in a short time period. | .642 | ||

Next, to assess the model fit criteria, reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity, a Confirmatory factor analysis using AMOS 20.0 software was conducted. The CFA results confirmed the five study-factors extracted from the previous EFA. All factors demonstrated adequate discriminant validity because the diagonal values were greater than the correlations. The composite reliability for each factor was also computed. In all cases the CR was above the minimum threshold of 0.70 Table 4.

Table 4.

Composite Reliability, Discriminant validity & Inter-Construct Correlations.

| CR | ASV | CLBRG | COSNCM | SIBND | PU | SR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLBRG | 0.888 | 0.416 | 0.772 | ||||

| COSNCM | 0.873 | 0.457 | 0.688 | 0.824 | |||

| SIBND | 0.785 | 0.430 | 0.701 | 0.771 | 0.753 | ||

| PU | 0.841 | 0.432 | 0.688 | 0.803 | 0.677 | 0.856 | |

| SR | 0.867 | 0.166 | 0.475 | 0.337 | 0.418 | 0.388 | 0.723 |

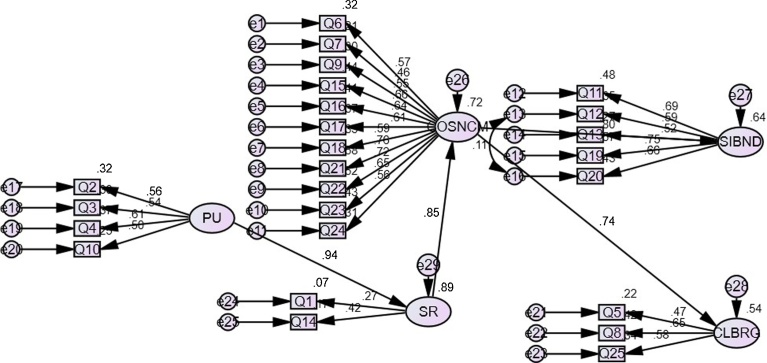

The goodness of fit measures for the model in Fig. 2. were also accepted in values (GFI = .901; CMIN/DF = 3.64; CFI = .97; RMSEA = .04; PCLOSE = .23; SRMR = 0.01).

Fig. 2.

The result of the proposed research model (standardized solution of SEM analysis).

6. Results

The study hypotheses were tested by examining the parameters provided by the structural model. Table 5. presents the standardized estimates indicating that the values are all significant at (P ≤ .001), thus supporting the study hypotheses.

Table 5.

Standardized estimates (R2) effects.

| Effect | R2 | Significance | Hypotheses | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PU → SR | .89 | *** | H1 | supported |

| SR → COSNCM | .72 | *** | H2 | supported |

| COSNCM → SIBND | .64 | *** | H3 | supported |

| COSNCM → CLBRG | .54 | *** | H4 | supported |

| COSNCM → SI | .64 | *** | H5 | (supported through H3) |

A significant positive relationship between the Perceived Usefulness of Facebook (PU) and its use for Social Relations (SR) was found (R2 = .89; p ≤ .001) also, there was a strong positive relationship between Social Relations (SR) and the use of Facebook for Collaborating, Sharing News and Communicating (COSNCM) between dispersed Syrians (R2 = .72; p ≤ .001), thus supporting H1 and H2 . The structural link from Collaborating, Sharing News and Communicating (COSNCM) to Social Identity, and to Bonding social capital (SIBND) through the use of Facebook is strong, positive and significant (R2 = .64; p ≤ .001), thus, supporting H3 and H5. Similarly, as hypothesized in H4, a strong positive and significant relationship was found between the use of Facebook for Collaborating, Sharing News, Communicating (COSNCM) with other Syrians and Bridging Syrian social capital CLBRG (R2 = .54; p ≤ .001).

7. Discussion and conclusions

This study examined the perceived usefulness of Facebook in maintaining Syrian social capital. Results established that Facebook enhanced social relationships and impacted the bonding and bridging of a Syrian nation war-torn social capital.

Syrians adopted Facebook because they believed in its perceived usefulness for enhancing their social relations (e.g., making new friends and maintaining the existing ones, keeping in touch with old friends, and finding lost contacts because of the Syrian crisis). Thus, similar to past studies, social relations was found to be an important factor that has a significant positive influence on Facebook usage similar to past studies (Hew, 2011; Selwyn, 2009). In addition, social relations affected Facebook’s usage for communication, collaboration, news and material sharing with other Syrian populations regardless of distances. This result is consistent with past research that found Facebook was used primarily for social reasons (e.g., following friends, maintaining connections with others and making new friends) (Mazman and Usluel, 2010) where Syrian Facebook users drew resources and information from their online relationships and networks with other Syrians.

The result that social identity loaded with the bonding of social capital indicates the strength of the relationship between the two constructs and implies that Facebook, according to the social identity theory, maintained social identity with individuals who enjoy mutual interests and tightly-knit close relationships (e.g., family members, close friends and ethnicity), with an emotional significance attached to that membership, or categorization, and a sense of belonging with an in-group that reflects commitment to the group, for the goal of providing each other with emotional support. This can be also be explained based on cultural values. According to Hofstede (2001) Syria is a highly collectivist culture. Collectivist values were found to be the most powerful in explaining attitudes and practices of societies (Taras et al., 2010). Individuals in collectivistic societies are expected to follow the norms associated with their respective cultures (Merkin and Ramadan, 2016). Thus, collectivists are more concentrated on their integration into their community and social networks (French et al., 2005). Individuals in strong cultures have shared values (Gill, 2013), thus, leading to increased understanding between them when communicating with each other (Gill, 2013), as their sense of selves becomes more interdependent with their collectivists groups (Markus and Kitayama, 1991). Hofstede’s (2001) collectivist values describe the connection individuals have with their groups “people from birth onwards are integrated into strong, cohesive in groups, which throughout people’s lifetime continue to protect them in exchange for unquestioning loyalty” (Hofstede, 2001)). Bonding social capital exists among homogeneous closely and emotionally connected cultures (Ellison et al., 2007; Williams, 2006). Thus, if we extrapolate collectivist values to social networks, Syrians will tend to express greater social confirmation in their relationships (Gudykunst and Nishhida, 1986) due to that individuals in collectivist cultures establish relationships at earlier ages and maintain them for life (Smith, 2012). They tend to cooperate with members of in groups (Triandis, 1988) who in turn, exert more influence on individuals in collectivistic relationships (Forbes et al., 2011). In addition, to that social identity is stronger for individuals who hold collective values (Brewer, 2001), and they have major consequences on social capital as they are the basis for their formulation, and are the mechanism for effective social networks. Furthermore, the loading of social identity construct with the social capital bonding construct, and not with the bridging social capital construct, in the quantitative study, confirms the results from the qualitative study regarding Syrians being divided into two groups, and that this faultlines, or hypothetical dividends were created by individuals according to similarities (Lau and Murnighan, 1998), as faultlines, tends to emerge when the divide is strong between group members based on individuals favoring their own subgroup member (Thatcher and Patel, 2011), and outsiders are not allowed in (Johnston et al., 2013; Portes and Vickstrom, 2011). Moreover, when opportunities for faultlines exist, multiplication of social affiliations emerge, thus leading to intergroup conflict, especially in pluralistic societies where the assimilation of individuals is more likely to happen within those who are part of a majority group opposed to those who are in minority groups (Al Ramiah et al., 2011). Thus, both groups become in constant flux and conflict, promoting hate speech between each other. Thus, Facebook facilitated the categorizing of people void of any significant meaning making minimal groups see themselves more favorably in comparison to other groups according to (Billig and Tajfel, 1973), which is not always useful in today’s globalized world. On the other hand, the loading of the collaboration items with the bridging social capital construct indicates that collaboration on Facebook among Syrians enhances social ties with loose-knit relationships.

Results have important implications for helping scattered nations and populations in the future. Facebook managers should develop strategies for overcoming its negative use. Facebook should be used for resolving conflicts and opening communications between different opposed groups for the aim of achieving better bonding and bridging of social capital. Facebook is a good platform to show different or opposed opinions, and people ought to resolve their conflicts offline when they come into real life, face-to-face encounter.

7.1. Limitations

This study used the self-reporting method which could have limitations of social desirability effects. Another limitation related to this study is sample composition. Although all participants were Syrians, data could not be obtained regarding the origins of participants (e.g., Syrians born/or living in urban environments differ significantly in their mentality and perceptions from those who were born/or were living in rural environments, or were born outside), these differences in environmental backgrounds could be the reason that some individual items of the scales, that had similar meaning, were perceived differently from different participants.

Religion and ethnic backgrounds are starting to have strong influence on the daily lives of people in Syria and in different countries of the Arab world. Therefore, future studies should explore the role of religion and ethnic backgrounds on Arab social capital.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Reem Ramadan: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Mr. Jawdat Aita, for distributing and helping in monitoring the survey on Facebook. I would also like to thank all those inside and outside Syria who helped in the dissemination of the survey which are too many to mention by name.

References

- Adler P.S., Kwon S.-W. Social capital: prospects for a new concept. Acad. Manage. Rev. 2002;27(1):17. [Google Scholar]

- Al Ramiah A., Hewstone M., Schmid K. Social identity and intergroup conflict. Psychol. Stud. 2011;56(1):44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Arab social media report . vol. 1. 2011. p. 1.http://www.arabsocialmediareport.com/home/index.aspx.pdf (Dubai School of Government). Retrieved June 18, 2016, from. [Google Scholar]

- Arab Social Media Report . 2015. Arab Social Media Influencers Summit.http://dmc.ae/img/pdf/white-papers/ArabSocialMediaReport Retrieved June 18, 2016, from. [Google Scholar]

- Bessière K., Kiesler S., Kraut R., Boneva B.S. Effects of internet use and social resources changes in depression. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2008;11(1):47–70. [Google Scholar]

- Billig M., Tajfel H. Social categorization and similarity in intergroup behaviour. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1973;3(1):27–52. [Google Scholar]

- Bögenhold D. Social capital and economics: social values, power, and social identity. J. Econ. Issues. 2015;49(3):875–877. Asimina Christoforou and John B. Davis eds. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer M.B. Superordinate goals versus superordinate identity as bases of intergroup cooperation. In: Capozza D., Brown R., editors. Social Identity Processes: Trends in Theory and Research. Sage; London: 2001. pp. 117–132. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer M.B. The psychology of prejudice: ingroup love and outgroup hate? J. Soc. Issues. 2002;55(3):429–444. [Google Scholar]

- Brislin R.W. The wording and translation of research instrument. In: Lonner W.J., Berry J.W., editors. Field Methods in Coss-cultural Research. Sage; Beverly Hills, CA: 1986. pp. 137–164. [Google Scholar]

- Burke M., Marlow C., Lento T. Social network activity and social well-being. Proc. CHI 2010. 2010:19021912. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty B. FoxNews.com; 2015. Us under New Pressure to Absorb Syrian Refugees as Europe Faces Crisis. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung C.M.K., Liu I.L.B., Lee M.K.O. How online social interactions influence customer information contribution behavior in online social shopping communities: a social learning theory perspective. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2015;66(12):2511–2521. [Google Scholar]

- Clopton A.W., Finch B.L. Are college students ‘bowling alone?' Examining the contribution of team identification to the social capital of college students. J. Sport Behav. 2010;33(4):377–402. [Google Scholar]

- CNNtech (2017). Retrieved September 10, 2017, from http://money.cnn.com/2017/08/17/technology/culture/facebook-hate-groups/index.html.

- Coleman J.S. Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am. J. Sociol. 1988;94(s1):S95. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J.M., Strauss A.L. 2015. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J.W. 2008. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods. [Google Scholar]

- Damian E., Van Ingen E. Social network site usage and personal relations of migrants. Societies. 2014;4(4):640–653. [Google Scholar]

- Davis F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989;13(3):319. [Google Scholar]

- DeKerckhove Derrick. Somerville House Books; Toronto, Canada: 1997. Connected Intelligence: The Arrival of the Web Society. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz Andrade A., Doolin B. Information and communication technology and the social inclusion of refugees. MIS Q. 2016;40(2):405–416. [Google Scholar]

- Donath J., Boyd D. Public displays of connection. BT Technol. J. 2004;22(4):71–82. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison N.B., Steinfield C., Lampe C. The benefits of Facebook Friends: social capital and college Students’ use of online social network sites. J. Comput. Mediated Commun. 2007;12(4):1143–1168. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison N.B., Steinfield C., Lampe C. Connection strategies: social capital implications of Facebook-enabled communication practices. New Media Soc. 2011;13(6):873–892. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison N.B., Vitak J., Gray R., Lampe C. Cultivating social resources on social network sites: facebook relationship maintenance behaviors and their role in social capital processes. J. Comput. Mediated Commun. 2014;19(4):855–870. [Google Scholar]

- Engadget (2017). Retrieved September 4, 2017, from https://www.engadget.com/2017/08/15/facebook-and-reddit-ban-hate-groups/.

- Eriksson M. Managing collective trauma on social media: the role of Twitter after the 2011 Norway attack. Media Cult. Soc. 2015;38(3):365–380. [Google Scholar]

- Evans N.J., Jarvis P.A. The group attitude scale: a measure of attraction to group. Small Group Res. 1980;17(2):203–216. [Google Scholar]

- Everitt B., Howell D.C. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 2006. Encyclopedia of Statistics in Behavioral Science. [Google Scholar]

- Facebook . 2016. Press Room: About Facebook.http://Facebook.com/press.php Retrieved June 22, 2016, from. [Google Scholar]

- Facebook (2017). Retrieved September 5, 2017, from https://www.facebook.com/notes/facebook-safety/controversial-harmful-and-hateful-speech-on-facebook/574430655911054/.

- Fast company (2017). Retrieved September 3, 2017, from https://www.fastcompany.com/4037115/why-facebook-tolerates-what-the-southern-poverty-law-center-calls-hate-groups.

- Feitosa J., Grossman R., Coultas C., Salazar M.R., Salas E. Integrating the fields of diversity and culture: a focus on social identity. Ind. Org. Psychol.: Perspect. Sci. Pract. 2012;5:371–374. [Google Scholar]

- Feitosa J., Salazar M.R., Salas E. Social identity: clarifying its dimensions across cultures. Psychol. Top. 2012;21(3):527–548. [Google Scholar]

- Ferdman B.M., Sagiv L. Diversity in organizations and cross-cultural work psychology: what if they were more connected? Ind. Org. Psychol.: Perspect. Sci. Pract. 2012;5(3):323–345. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M., Ajzen I. Addison-Wesley; Reading, MA: 1975. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes G.B., Collinsworth L.L., Zhao P., Kohlman S., LeClaire J. Relationships among individualism-collectivism, gender, and in group/outgroup status, and responses to conflict: a study in china and the United States. Aggress. Behav. 2011;37(4):302–314. doi: 10.1002/ab.20395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French D., Pidada S., Victor A. Friendships of Indonesian and United States youth. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2005;29(4):304–313. [Google Scholar]

- Furlong P., Putnam R.D., Leonardi R., Nanetti R.Y. Making democracy work: civic traditions in modern Italy. Int. Aff. (R. Inst. Int. Aff. 1944-) 1994;70(1):172. [Google Scholar]

- Gerard H.B., Hoyt M.F. Distinctiveness of social categorization and attitude toward ingroup members. J. Personal. and Soc. Psychol. 1974;29(6):836–842. [Google Scholar]

- Gill T.G. Culture, complexity: and informing: how shared beliefs can enhance our search for fit- ness. Inf. Sci.: Int. J. Emerg. Trans. Discip. 2013;16:71–98. [Google Scholar]

- Graeff P., Svendsen G.T. Trust and corruption: the influence of positive and negative social capital on the economic development in the European Union. Qual. Quant. 2012;47(5):2829–2846. [Google Scholar]

- Gudykunst W.B., Nishhida T. Attributional confidence in low- and high-context cultures. Hum. Commun. Res. 1986;12(4):525–549. [Google Scholar]

- Hair J., Anderson R., Tatham L., Black W. 4th ed. Prentice Hall; London: 1995. Multivariate Data Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Hancock J., Toma C., Fenner K. I know something you don't: the use of asymmetric personal information for interpersonal advantage. Proc. CSCW’08; ACM, New York; 2008. pp. 413–416. [Google Scholar]

- Helliwell J.F., Putnam R.D. The social context of well-being. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2004;359(1449):1435–1446. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hew K.F. Students and teachers use of Facebook. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011;27(2):662–676. [Google Scholar]

- Hobman E.V., Bordia P. The role of team identification in the dissimilarity- conflict relationship. Group Process. Intergr. Relat. 2006;9:483–508. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede G. Empirical models of cultural differences. In: Bleichrodt N., Drenth P.D., Bleichrodt N., Drenth P.D., editors. Contemporary Issues in Cross-cultural Psychology. Swets & Zeitlinger Publishers; Lisse, Netherlands: 1991. pp. 4–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede G. Sage Publications Inc; Thousand Oaks: 2001. Cultures Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations. [Google Scholar]

- Hollenbaugh E.E., Ferris A.L. Facebook self-disclosure: examining the role of traits, social cohesion, and motives. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014;30:50–58. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins N., Reicher S. Identity, culture and contestation: social identity as cross-cultural theory. Psychol. Stud. 2011;56(1):36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Huysman M., Wulf V., editors. Social Capital and Information Technology. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston K., Tanner M., Lalla N., Kawalski D. Social capital: the benefit of Facebook friends. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2013;32(1):24–36. [Google Scholar]

- Katz E., Blumler J.G., Gurevitch M. Uses and gratifications research. Public Opin. Q. 1973;37(4):509. [Google Scholar]

- Kelloway E. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1998. Using LISREL for Structural Equation Modeling. [Google Scholar]

- Knapp M.L., Vangeslisti A.L. vol. 5. Allyn and Bacon; Boston: 2003. (Interpersonal Communication and Human Relationships). [Google Scholar]

- Lau D.C., Murnighan J.K. Demographic diversity and faultlines: the compositional dynamics of organizational groups. Acad. Manage. Rev. 1998;23(2):325–340. [Google Scholar]

- Lee M.J.W., McLoughlin C. Harnessing the affordances of Web 2.0 and social software tools: can we finally make student centered learning a reality?. Paper presented at the World Conference on Educational Multimedia; Hypermedia and Telecommunications, Vienna, Austria; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.A., Efstratiou C., Bai L. OSN mood tracking. Proceedings of the 2016 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing Adjunct − UbiComp ‘16. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Levine J.M., Moreland R.L. Small groups. In: Gilbert D., Fiske S., Lindzey G., editors. Handbook of Social Psychology. McGraw-Hill; Boston, MA: 1998. pp. 415–469. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Beck M.S., Bryman A., Liao T.F. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2011. The Sage Encyclopedia of Social Science Research Methods. [Google Scholar]

- Lin N. Building a network theory of social capital. Connections. 1999;22:28–51. [Google Scholar]

- Lomas J. Social capital and health: implications for public health and epidemiology. Soc. Sci. Med. 1998;47(9):1181–1188. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00190-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus H.R., Kitayama S. Culture and the self: implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1991;98(2):224–253. [Google Scholar]

- Mazman S.G., Usluel Y.K. Modeling educational usage of Facebook. Comput. Educ. 2010;55(2):444–453. [Google Scholar]

- Merkin R., Ramadan R. Communication practices in the US and Syria. SpringerPlus. 2016;5(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-2486-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald D.L., Clark E.M., Kelly C.M. Friendship maintenance: an analysis of individual and dyad behaviors. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2004;23(3):413–441. [Google Scholar]

- Papacharissi Z. We have always been social. Soc. Media + Soc. 2015;1(1) [Google Scholar]

- Paxton P. Is social capital declining in the United States? A multiple indicator assessment. Am. J. Sociol. 1999;105(1):88–127. [Google Scholar]

- Pepper M.B., Leithauser A., Loroz P.S., Steverson B. Responding to hate speech on social media. Int. J. Cyber Ethics Educ. 2012;2(4):45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Portes A., Vickstrom E. Diversity, social capital, and cohesion. Ann. Rev. Sociol. 2011;37(1):461–479. [Google Scholar]

- Procopio C.H., Procopio S.T. Do you know what it means to Miss New Orleans? Internet communication, geographic community, and social capital in crisis. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2007;35(1):67–87. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam R.D. Tuning in, tuning out: the strange disappearance of social capital in America. PS: Polit. Sci. Polit. 1995;28(4):664. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam R.D. Simon & Schuster; New York, NY: 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. [Google Scholar]

- Recuero R., Araujo R., Zago G. How does social capital affect retweets? Weblogs and Social Media, 2011 AAAI Fifth International Conference. 2011:305–312. AAAI. [Google Scholar]

- Satyanath S., Voigtlaender N., Voth H. 2013. Bowling for Fascism: Social Capital and the Rise of the Nazi Party. [Google Scholar]

- Selwyn N. Faceworking: exploring students’ education-related use of Facebook. Learn. Media Technol. 2009;34(2):157–174. [Google Scholar]

- Smith P.B. Cross-cultural perspectives on identity. In: Schwartz S.J., Luyckx K., Vignoles V.L., editors. vol. 1. Springer; New York: 2012. pp. 249–265. (Handbook of identity theory and research). [Google Scholar]

- Social watch . 2017. Social Degradation Report.http://www.socialwatch.org/node/17648 Retrieved August 28, 2017, from. [Google Scholar]

- Sohrabi B., Gholipour A., Amiri B. The influence of information technology on organizational behavior: study of identity challenges in virtual teams. Int. J. E-Collab. 2011;7(2):19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Stefanone M.A., Jang C.-Y. Writing for friends and family: the interpersonal nature of Blogs. J. Comput. Mediated Commun. 2007;13(1):123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Steinfield C., Ellison N.B., Lampe C. Social capital, self-esteem, and use of online social network sites: a longitudinal analysis. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2008;29(6):434–445. [Google Scholar]

- Subrahmanyam K., Reich S.M., Waechter N., Espinoza G. Online and offline social networks: use of social networking sites by emerging adults. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2008;29(6):420–433. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H. Academic Press; London: 1978. Differentiation Between Social Groups. [Google Scholar]

- Taras V., Kirkman B.L., Steel P. Examining the impact of culture’s consequences: a threedecade, multi-level, meta-analytic review of Hofstede’s cultural value dimensions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010;95:405–439. doi: 10.1037/a0018938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tausch A. 2015. Europe’s Refugee Crisis. Zur aktuellen politischen Ökonomie von Migration, Asyl und Integration in Europa (Europe’s Refugee Crisis. On the Current Political Economy of Migration, Asylum and Integration in Europe) [Google Scholar]

- Thatcher S.M.B., Patel P.C. Demographic faultlines: a meta-analysis of the literature. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011;96:1119–1139. doi: 10.1037/a0024167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The guardian. (2017). Retrieved September 10, 2017, from https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/jul/31/extremists-neo-nazis-facebook-groups-social-media-islam.

- Triandis H. Westview Press; Boulder: 1988. Individualism and Collectivism. [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (2016). Retrieved August 20, 2016, from http://www.unhcr.org/559d67d46.html.

- UNHCR United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (2017). Retrieved September 3, 2017, from http://www.unhcr.org/559d67d46.html.

- Valenzuela S., Park N., Kee K.F. Is there social capital in a social network site? Facebook use and college students’ life satisfaction, trust, and participation. J. Comput. Mediated Commun. 2009;14(4):875–901. [Google Scholar]

- Wellman B., Haase A.Q., Witte J., Hampton K. Does the Internet increase, decrease, or supplement social capital? Social networks, participation, and community commitment. American Behavioral Scientist. 2001;45(3):436–455. [Google Scholar]

- Wilding R., Gifford S.M. Introduction. J. Refugee Stud. 2013;26(4):495–504. [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. On and off the ’net: scales for social capital in an online era. J. Comput. Mediated Commun. 2006;11(2):593–628. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson R.E., Gosling S.D., Graham L.T. A review of Facebook research in the social sciences. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2012;7(3):203–220. doi: 10.1177/1745691612442904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolcock M. Social capital in theory and practice: reducing poverty by building partnerships between states. Mark. Civil Soc. 2002:3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng L., Starbird K., Spiro E.S. Rumors at the speed of light? Modeling the rate of rumor transmission during crisis. 2016 49th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS) 2016 [Google Scholar]