Abstract

Setting: A provincial tertiary hospital in Gauteng province, South Africa, with a high burden of tuberculosis (TB) patients and high risk of TB exposure among health care workers (HCWs).

Objective: To determine HCWs' adherence to recommended TB infection prevention and control practices, TB training and access to health services and HCW TB rates.

Design: Interviews with 285 HCWs using a structured questionnaire as part of a large, international mixed-methods study.

Results: Despite 10 HCWs (including seven support HCWs) acquiring clinical TB during their period of employment, 62.8% of interviewees were unaware of the hospital's TB management protocol. Receipt of training was low (34.5% of all HCWs and <5% of support HCWs trained on TB transmission; 27.5% of nurses trained on respirator use), as was use of respiratory protection (44.5% of HCWs trained on managing TB patients). Support HCWs were over 36 times more likely to use respiratory protection if trained; nurses who were trained were approximately 40 times more likely to use respirators if they were readily available.

Conclusion: Improved coordination and uptake of TB infection prevention training is urgently needed, especially for non-clinical HCWs in settings of regular exposure to TB patients. Adequate supplies of appropriate respiratory protection must be made available.

Keywords: health care workers, occupational tuberculosis, TB infection prevention and control

Abstract

Contexte : Un hôpital provincial de niveau tertiaire dans la province de Gauteng, Afrique du Sud avec de très nombreux patients avec tuberculose (TB) et un risque élevé d'exposition à la TB parmi les travailleurs de santé (HCW).

Objectif : Déterminer l'observance des HCW vis-à-vis des pratiques recommandées de prévention de l'infection et de lutte contre la TB, la formation en matière de TB et l'accès aux services de santé, et le taux de TB chez les HCW.

Schéma : Entretiens avec 285 HCW, basés sur un questionnaire structuré, dans le cadre d'une vaste étude internationale à multiples méthodes.

Résultats : Bien que 10 HCW (dont sept personnels de soutien) aient eu une TB pendant leur période de travail, 62,8% des répondants n'étaient pas au courant du protocole de prise en charge de la TB dans l'hôpital. La couverture de la formation a été faible (34,5% de tous les HCW et moins de 5% des HCW de soutien sur la transmission de la TB ; 27,5% des infirmiers sur l'utilisation d'un masque respiratoire), tout comme l'utilisation d'une protection respiratoire (44,5% des HCW prenant en charge des patients TB). Les HCW de soutien ont été 36 fois plus susceptibles d'utiliser une protection respiratoire s'ils avaient été formés ; les infirmiers qui avaient été formés ont été environ 40 fois plus susceptibles d'utiliser des masques respiratoires s'ils étaient facilement disponibles.

Conclusion : Une amélioration de la coordination et de la couverture de la formation à la prévention de l'infection TB est requise d'urgence, surtout pour les HCW de soutien dans les contextes d'exposition régulière aux patients TB. Des stocks suffisants de protection respiratoire doivent être disponibles.

Abstract

Marco de referencia: Un hospital provincial de atención terciaria en la provincia de Gauteng de Suráfrica, donde se observa una alta carga de morbilidad por tuberculosis (TB) y un alto riesgo de exposición de los profesionales de salud (HCW) a la enfermedad.

Objetivo: Evaluar la observancia de las prácticas de prevención y control de la infección tuberculosa, la capacitación en materia de TB y el acceso de los HCW a los servicios de atención y calcular la tasa de TB en este tipo personal.

Método: Se entrevistaron 285 HCW mediante un cuestionario estructurado, en el marco de un extenso estudio internacional por métodos mixtos.

Resultados: Pese a que 10 HCW (incluidos siete miembros del personal auxiliar) habían adquirido la enfermedad tuberculosa durante el período de su empleo, el 62,8% de los entrevistados no conocía el protocolo de manejo de la TB del hospital. La tasa de capacitación era baja (34,5% de todos los HCW y menos de 5% del personal auxiliar sobre la transmisión de la TB y 27,5% del HCW sobre la utilización de mascarillas respiratorias) y asimismo la utilización de la protección respiratoria (el 44,5% de los HCW que se ocupaban de pacientes con TB). La probabilidad de que personal auxiliar utilizara la protección respiratoria era 36 veces mayor al haber recibido capacitación; el personal de enfermería tenía una probabilidad 40 veces mayor de utilizar las mascarillas respiratorias cuando había sido formado y el material estaba al alcance.

Conclusión: Se precisa con urgencia una mejor coordinación y una utilización más amplia de la formación sobre la prevención de la infección tuberculosa, sobre todo dirigida a los HCW auxiliares, en los entornos donde es corriente la exposición a pacientes tuberculosos. Es necesario contar con los suministros adecuados de protección respiratoria al alcance del personal.

Despite international attention on the importance of strengthening the global health care workforce by agencies such as the High Level Commission on Health Employment and Economic Growth, tuberculosis (TB) transmission in health care settings remains a serious concern in many countries.1 Evidence indicates that health care workers (HCWs) are at increased risk of acquiring TB2–6 in settings where they are systematically exposed to both undiagnosed and diagnosed TB patients.7 In response to this, TB infection prevention and control (IPC) measures are internationally recommended, including training on the mode of transmission and TB infection prevention as a part of the hierarchy of TB infection control.8 In South Africa, the National Tuberculosis Management Guidelines recommend that HCWs be educated on the symptoms, prevention and treatment of TB.9

Despite widespread endorsement of TB IPC recommendations, few studies10,11 have explored the extent to which TB IPC training has been embraced and whether practices are actually being implemented and supported.1 Moreover, evidence regarding the effectiveness of education on compliance with TB IPC practices remains mixed. A literature review of 39 studies found no evidence linking training with either adherence to IPC practice or reductions in infection rates.12 A more recent systematic review, however, indicated that training was effective in improving workers' occupational health practices. Another study13 reported a positive impact of education on knowledge, attitude and practices related to occupational health among 150 HCWs,14 and more recent evidence supports lower HCW TB rates associated with IPC training.3

In this study, we aimed to explore, first, factors associated with the development of TB among HCWs in a provincial tertiary hospital, including availability of TB personal protective equipment (PPE) in the hospital and factors associated with its adherence; and second, training related to TB IPC across occupations and departments, and, most importantly, the association of training and practice within the different HCW groups and factors associated with the use of respirators. Finally, availability of and attitudes toward the provision of health services for HCWs with TB were considered, along with reflections on the reported rate of TB among the HCWs in this study.

METHODS

This study was part of an international collaborative project that included measuring TB in the air throughout a provincial tertiary hospital in Gauteng province, South Africa, which indicated a widespread presence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the facility, with five (50%) air samples tested for TB in the breathing zone of medical doctors and three (23%) in the breathing zone of nurses yielding positive results.15 The 762-bed hospital employs 2000 HCWs, conducts about 192 000 consultations annually in its out-patient and emergency departments, and had 276 960 admissions, with approximately 905 TB patients, in 2015 and an unknown number of undiagnosed patients with TB. This study was originally designed to provide a baseline workplace assessment for TB IPC upon which to design future appropriate interventions. Day and night shift HCWs in selected wards were invited to participate in the study.

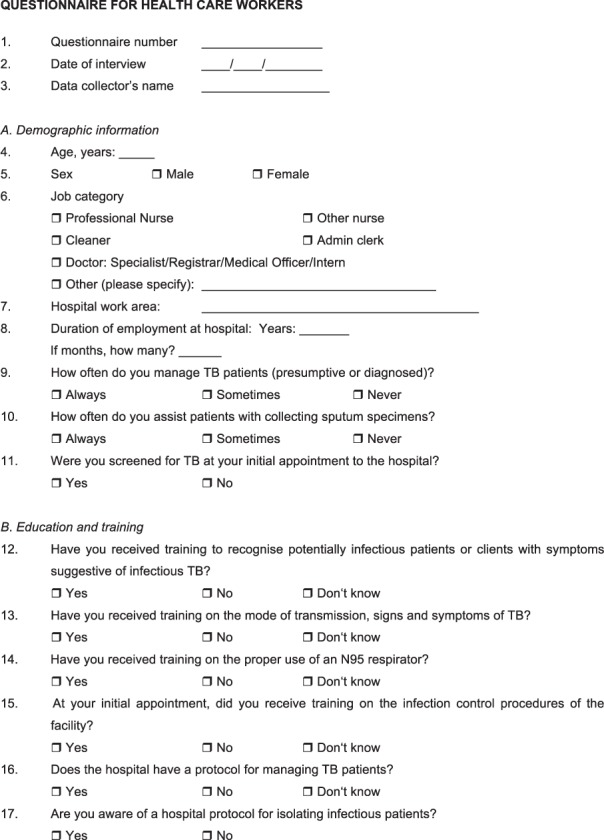

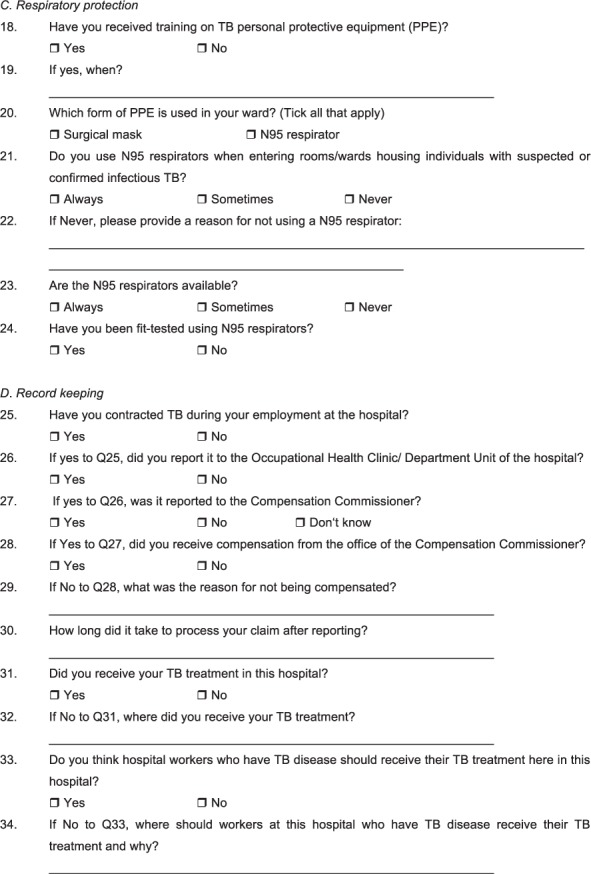

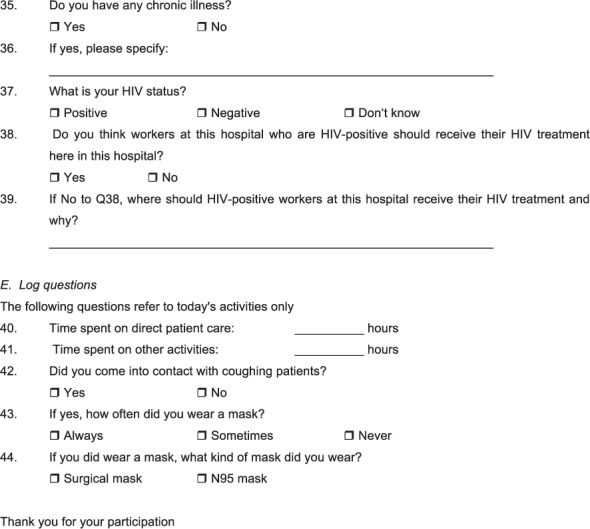

Data were collected using an interviewer-administered structured questionnaire in English (Appendix). All HCWs who were present during day and night shifts in the selected study wards (emergency, theatre, intensive care unit [ICU], paediatrics, medical, surgical, laboratory and TB focal point) on the day of data collection were invited to participate. Data were collected from night and day shift staff over a period of 2 weeks.

Data were analysed using SPSS v. 24 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Univariate analyses were performed to check for normality and skewness. Differences between categorical variables were assessed with Pearson's χ2 test or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. Logistic regression was used to model the association between various covariates such as training on the mode of TB transmission and the use of respiratory protection, with the odds ratio being a measure of this association. Covariates were entered as independent variables in the multivariable regression model to obtain adjusted effects. Variables were selected by applying backward stepwise regression (likelihood ratio) to eliminate variables not deemed statistically significant with P = 0.05 for entry and P = 0.10 for elimination. As clinical and non-clinical HCWs have very different exposure profiles, the regression model was also run separately for each group. The Nagelkerke pseudo R2 statistic is provided to report the explanatory power of each model application.

Ethical clearance for the study was granted by the University of Pretoria Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee (Pretoria, South Africa, ethics reference no 136/2013) as well as the Research Ethics Board at the University of British Columbia (Vancouver, BC, Canada, ID H13-01260). Written informed consent was provided by all participating HCWs.

RESULTS

Participants' characteristics

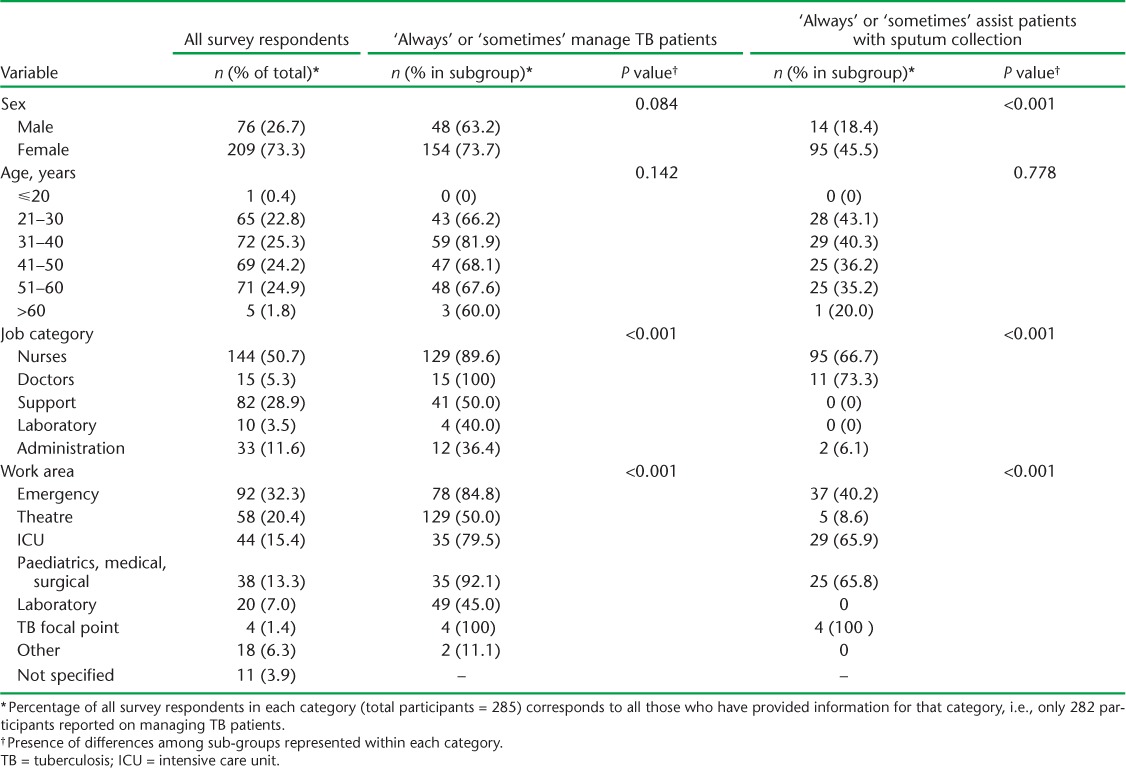

Of 377 eligible HCWs, 285 participated in the study, a response rate of 75.6%. Two hundred and nine (73.3%) of the participants were female, the mean age was 41.4 years (range 20–64 years), with nurses accounting for 50.7% of participants (Table 1). The study sample represented a cross-section of work environments in the study wards, encompassing clinical professionals as well as non-clinical occupations aggregated in support, laboratory and administrative sub-groupings.

TABLE 1.

TB exposure risk by participants' characteristics

Risk of tuberculosis exposure

Almost all clinical personnel (89.6% of the nurses and 100% of the doctors) indicated that they had regular contact with TB patients, and 66.7% of the nurses and 73.3% of the doctors reported that they performed direct collection of sputum specimens. Significantly, extensive exposure to TB patients was reported by other job categories as well, with half (50%) of support workers (porters, cleaners, security, etc.) indicating at least some regular exposure to TB patients (Table 1).

Substantial exposure to TB patients was reported across all study wards, although it was most extensive in units such as medical wards, where known TB patients were present, as well as areas such as the emergency (casualty) department, where contact with unconfirmed TB cases is common.

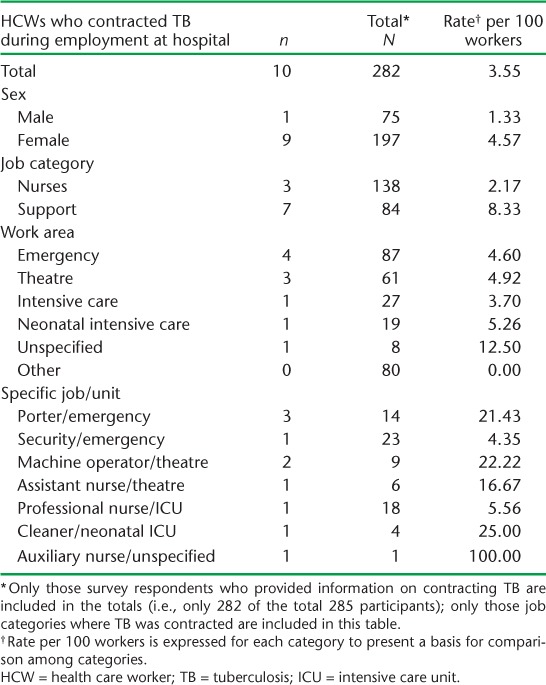

Health care workers acquiring tuberculosis

The potential seriousness of exposure risk is highlighted in Table 2: 3.6% (10/282 respondents to this question) of the HCWs reported contracting TB during their employment at the hospital. Nearly 1 in 10 support staff had contracted TB (8.3%, 7/84) as had 2.2% (3/138) of the nurses. In the emergency department, 21.4% (3/14) of the porters and 4.3% (1/23) of the security guards, as well as 22.2% (2/9) of the machine operators from the operating theatre, also contracted TB during employment. None of the 15 doctors who participated in the survey reported contracting TB during their employment.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of HCWs who contracted TB during employment at the hospital

All 10 TB-infected HCWs reported receiving treatment, but only three were treated at the hospital where they worked. Nevertheless, nine of the 10 HCWs indicated that anti-tuberculosis treatment should be provided at the hospital, concurring with the expressed preference (92.6%) of those who were not infected.

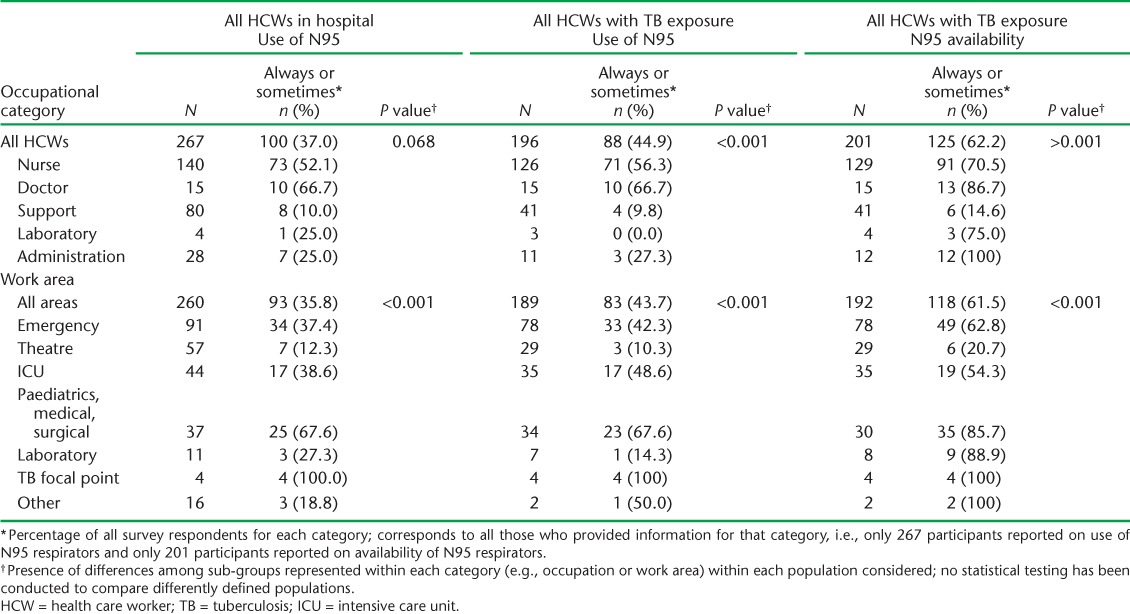

Protection against tuberculosis exposure

Table 3 summarises the extent to which HCWs comply with the use of N95 respirators, the recommended respiratory protection for exposure to TB. Fewer than half (44.9%) of the HCWs reported ever using respirators when managing patients with confirmed or presumptive TB. The frequency with which clinical staff ‘always’ or ‘sometimes’ wore respirators in such circumstances was only 56.3% among nurses and 66.7% among doctors. Notably, the rate of usage was dramatically lower for other HCWs, with fewer than one in 10 (9.8%) of all support (non-direct patient care) workers reporting that they ever used respirators.

TABLE 3.

HCWs' use of N95 respirators and availability

Considerable variation in HCW use of respiratory protection when managing confirmed or presumptive TB cases is evident in different units (Table 3), with the highest usage reported in the TB focal point (100%), followed by the paediatrics/medical/surgical wards (67.6%). Only 62.2% of the HCWs reported that N95 respirators were always or sometimes available, while only 14.6% of support workers with TB exposure reported that respirators were available in their work area. Some areas, such as the diagnostic laboratory, which is administered separately as part of the National Health Laboratories Service network of 268 laboratories across nine provinces in South Africa,16 reported good availability of N95 respirators (88.9%), with exposure to blood and body fluids from specimens being the primary exposure risk here.

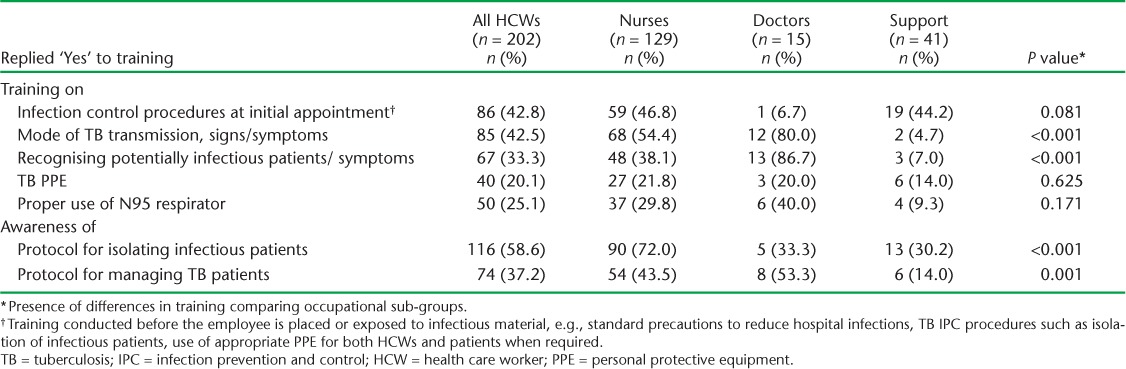

Training and other measures to promote TB infection prevention and control

Table 4 documents the proportion of HCWs who received training related to awareness and minimisation of TB workplace exposure. Fewer than half (42.8%) of all HCWs who reported contact with TB patients received some TB IPC training, with only 20% receiving instruction on PPE in general, or more specifically on the proper use of the N95 respirator (25.1%). Only 29.8% of nurses, the group with the most intensive contact with confirmed and presumed TB patients, indicated that they had been trained on the proper use of N95 respirators. Clinical staff were more likely to receive training than non-clinical support workers on mode of transmission and how to recognise potentially infectious patients. Apart from training on infection control procedures at their initial appointment (44.2%), support workers received only marginal training on modes of transmission (4.7%) and PPE (14.0%). Only 37.2% of all the HCWs were aware of a protocol for managing TB patients, with clinical staff (nurses 43.5%, doctors 53.3%) being more likely to be better informed than support workers (14.0%).

TABLE 4.

Training and awareness regarding TB IPC by occupation of HCWs encountering TB patients

Influences on the adoption of protective measures

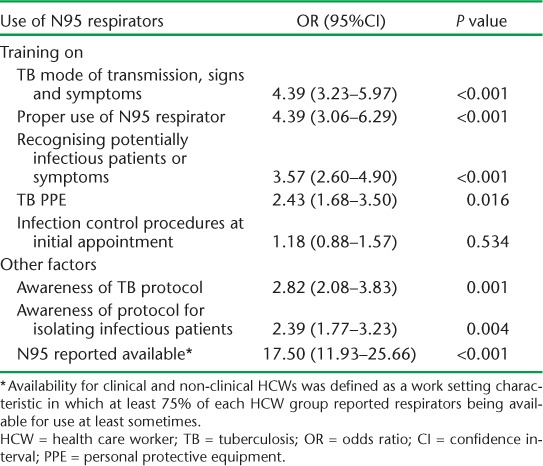

Despite the limited training received by most HCWs, receipt of all types of training in TB IPC and awareness and availability of PPE were associated with an increased likelihood of using N95 respirators (Table 5). For example, HCWs who received training on modes of TB transmission, signs and symptoms were more than four times more likely to use an N95 respirator than those who did not receive this training (odds ratio [OR] 4.38, 95% confidence interval [CI] 3.23–5.94). Nevertheless, the most widely employed training in the hospital—on IPC procedures at initial appointment, provided to 42.8% of all employees managing TB patients—was only weakly associated with likelihood of N95 use, and was not statistically significant.

TABLE 5.

Association of training and other factors on use of N95 respirators * by HCWs normally facing exposure to TB patients

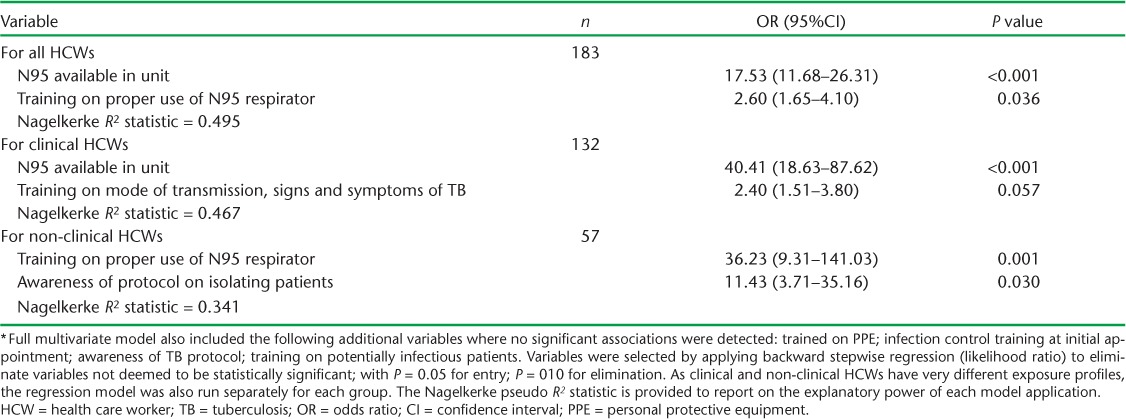

Recognising that clinical and non-clinical HCWs have different educational backgrounds and training cultures, a multivariable model was constructed to examine the effect of covariates on N95 use (Table 6). Survey results indicated that non-clinical HCWs (shown in Table 4 as having little training) were far more likely to report using respirators if they were trained in their proper use (OR 36.23, 95%CI 9.31–141.03). Doctors and nurses, who usually receive more training on respirator use, were far more likely to use respirators if they were readily available in their work setting (OR 40.41, 95%CI 18.63–87.62).

TABLE 6.

Multivariable model of factors associated with likelihood of HCW using N95 respirator when entering a room with presumed or confirmed TB patient *

DISCUSSION

This study confirms that exposure to TB is widespread in the health care settings included, and reveals that there is an urgent need to strengthen measures to provide protection for HCWs. Substantial exposure to TB patients was reported across all departments, although it was most extensive in units such as medical wards where known TB patients were present, as well as areas such as the emergency (casualty) department, where contact with possible but not yet confirmed TB cases is common.

Although doctors and nurses report a willingness to use respiratory protection, our findings demonstrate that HCWs do not always use respirators when required, suggesting that broader strategies for ensuring protection (e.g., adequate supply of N95 respirators, individual HCW behaviour change and culture change) need to be strongly promoted. For non-clinical staff who also have frequent exposure to TB patients, IPC training is extremely limited, implying that a risk-managed approach to educating support workers on occupational TB prevention is strongly warranted. The systematic review conducted by Joshi et al.1 supports this recommendation, which has been raised in other studies.17 Given the widespread hazard of exposure to TB patients in the facility, the measures taken to reduce HCWs' risk of acquiring TB as a result of such exposure assume particular importance and encompass not only clinical staff, who have the most regular contact with TB patients, such as in clinical examination, but also other workers who face exposure as incidental to performing their jobs.

With TB widespread in high-incidence countries such as South Africa, there is particular value in pursuing a comprehensive approach to reduce risk, including attention to implementing cost-effective and feasible TB IPC measures such as training in respiratory cough etiquette and patient triaging in addition to health and safety hierarchies, such as by improving ventilation. Administrative controls should be implemented as a priority, as it is imperative that the hospital pursue measures such as early recognition of people with TB symptoms, isolation of coughing patients, prompt investigation of patients presenting with TB symptoms, education of patients on respiratory hygiene and isolation of confirmed TB patients, screening and training of HCWs in TB signs and symptoms, route of transmission and TB IPC. In addition, the limited staff access to TB treatment in the facility, despite a preference for it to be available, suggests the presence of barriers to such uptake, as documented in previous studies.18,19 This suggests that HCWs need to be better informed about the hospital's occupational health clinic and the services available to them, in an effort to increase awareness and reporting, reassurance of staff as regards confidentiality by the occupational health clinic staff and that occupationally acquired TB in South Africa is listed under schedule three of the Compensation for Occupational Injuries and Diseases Act, No 130 of 1993,20 as a compensable disease.

Although our study design did not allow us to calculate the incidence rates of TB infection for the cohort of HCWs working at this facility, our findings should nevertheless be considered in relation to research indicating that HCWs in low- and middle-income countries are at high risk of contracting TB at work because of the burden of TB, the high prevalence of HIV amongst HCWs, and poor compliance with IPC procedures in over-crowded, over-burdened and under-resourced health care facilities.2,11 In South Africa, it has been estimated that HCWs are up to three times more likely to acquire TB than the general population,3,11,21 with O'Donnell et al. estimating a 5- to 6-fold higher rate of hospital admission with multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) or extensively drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB) compared to non-HCWs.22 This occurs despite clear regulations on occupational hazard control, such as the Regulations for Hazardous Biological Agents23 (HBA) introduced under South Africa's Occupational Health and Safety Act 85 of 1993.24

Similar findings to ours have been observed in another study conducted in South African primary health care facilities, where researchers identified a lack of TB IPC control training among health workers and poor compliance with the levels of infection control prioritised by the WHO.11,24 Engelbrecht et al. also found that, despite the availability of policies and guidelines, TB IPC measures are often poorly implemented in South African settings because of poor infrastructure, a lack of human resources, PPE limitations and budgetary constraints.25 Our study shows that high proportions of participants who care directly and indirectly for TB patients only infrequently use appropriate respiratory protection. Seale et al. found that, among other factors, the majority of the HCWs in their low TB incidence setting (Australia) also mentioned lack of training on the use of masks and respirators as a factor that influenced adherence.26 This is in contrast with findings in another low TB-incidence, high-income country by Bryce et al., where the majority of HCWs reported that they received sufficient to excellent training on the use of respirators, which were readily available.27

In the present study, most HCWs were not trained. It was also noted that respirators were not readily available; and when they were available, access was limited, with staff noting that N95 respirators were expensive and should not be re-used. Twenty five per cent of staff reported training in the use of N95 respirators, while 20% reported training on the general use of TB PPE. Although the N95 respirator is recommended as a TB PPE, the use of a surgical mask for patients with cough is also advised. The training most widely employed in the hospital (IPC procedures at initial appointment) was weakly associated with the likelihood of N95 use, and was not statistically significant—although other forms of training did appear to have effectiveness and merit. It is imperative for hospital management to ensure that HCWs have access to effective training, refresher courses and regular updates to increase compliance with respirator use. It is clear that different rates of adherence to TB prevention and infection control measures across studies relate both to training as well as access to respirators and other equipment and infrastructure needed for TB IPC. In this regard, identification of processes that promote implementation constitutes a particularly valuable research priority.

While the strength of this study lies precisely in examining actual implementation circumstances related to a noted area of concern, limitations of our survey included less participation of other occupational groups, such as doctors. The changeover from day to night work shifts was a challenge, as some of the HCWs in the wards that were sampled were missed on the day of data collection as they were either off-duty or working a day or night shift. Another limitation is that as the survey was based on self-reporting, participants may not accurately recall the various training courses related to TB that they attended. While this research was undertaken as a purposeful exercise, more systematic monitoring of TB IPC in ongoing administrative processes would greatly assist progress in improving the protection of HCWs.

CONCLUSION

The health care workforce, particularly in low- or middle-income countries, is at greater risk of contracting TB than the general public due to occupational exposure. Despite available policies and guidelines8,9 and the WHO health care workforce focus on training of HCWs, the gaps in the training of HCWs on how to protect themselves remain problematic. Lack of training is closely associated with lack of protection. Resources must be put in place to ensure that effective training is conducted and triaged, not only according to job category but also according to risk of exposure to TB. As part of the increased focus on the global health care workforce stimulated by the findings of the High-Level Commission on Health Employment and Economic Growth, much more attention is needed in this area.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the hospital management for allowing us to conduct the survey and all the HCWs who participated in the survey. The authors acknowledge the generous funding of this study, which was provided by the Canadian Institute of Health Research (Ottawa, ON, Canada) under grant ROH-115212.

APPENDIX

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none declared.

References

- 1. Joshi R, Reingold A L, Menzies D, Pai M.. Tuberculosis among health-care workers in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. PLOS Med 2006; 3: c494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Menzies D, Joshi R, Pai M.. Risk of tuberculosis infection and disease associated with work in health care setting. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2007; 11: 593– 605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. O'Hara L M, Yassi A, Zungu M, . et al. The neglected burden of tuberculosis disease among health workers: a decade-long cohort study in South Africa. BMC Infect Dis 2017; 17: 547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. O'Hara L M, Yassi A, Bryce E A, . et al. Infection control and tuberculosis in health care workers: an assessment of 28 hospitals in South Africa. Int J Tuberc Dis 2017; 21: 320– 326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wilkinson D, Gilks C F.. Increasing frequency of tuberculosis among staff in a South African district hospital: impact of the HIV epidemic on the supply side of health care. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1998; 92: 500– 502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Naidoo S, Jinabhai C C.. TB in health care workers in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2006; 10: 676– 682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bhebhe L T, Van Rooyen C, Steinberg J W.. Attitudes, knowledge and practices of healthcare workers regarding occupational exposure of pulmonary tuberculosis. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med 2014; 6: E1– E6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Health Organization. . Guidelines for the prevention of tuberculosis in healthcare facilities in resource-limited settings. WHO/CDS/TB/99.269 Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 1999. http://www.who.int/tb/publications/who_tb_99_269.pdf?ua=1 Accessed November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 9. TB DOTS Strategy Coordination, South Africa National Department of Health. . National tuberculosis management guidelines. Pretoria, South Africa: National Department of Health, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Reid M J, Saito S, Nash D, Scardigli A, Casalini C, Howard A A.. Implementation of tuberculosis infection control measures at HIV care and treatment sites in sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2012; 16: 1605– 1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Claassens M M, Van Schalkwyk C, du Toit E, . et al. Tuberculosis in healthcare workers and infection control measures at primary healthcare facilities in South Africa. PLOS ONE 2013; 8: e76272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ward D. The role of education in the prevention and control of infection: a review of the literature. Nurse Educ Today 2011; 31: 9– 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Robson L S, Stephenson C M, Schulte P A, Amick B C.. A systematic review of the effectiveness of occupational health and safety training. Scand J Work Environ Health 2012; 38: 193– 208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Suchitra J, Lakshmi Devi N.. Impact of education on knowledge, attitudes and practices among various categories of health care workers on nosocomial infections. Indian J Med Microbiol 2007; 25: 181– 187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Matuka O, Singh T, Bryce E, . et al. Pilot study to detect airborne Mycobacterium tuberculosis exposure in a South African public healthcare facility outpatient clinic. J Hosp Infect 2015; 89: 192– 196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. The National Health Laboratory Service. . Annual report, 2016/2017. Johannesburg, South Africa: National Health Laboratory Service; http://nhls.ac.za/ Accessed December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kanyerere H S, Salaniponi F M.. Tuberculosis in health care workers in a central hospital in Malawi. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2003; 7: 489– 492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. World Health Organization. . The joint WHO-ILO-UNAIDS policy guidelines on improving health workers' access to HIV and tuberculosis prevention, treatment, care and support services: a guidance note. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Khan R, Yassi A, Engelbrecht M C, Nophale L, van Rensburg A J, Spiegel J.. Barriers to HIV counselling and testing uptake by health workers in three public hospital in Free State Province, South Africa. AIDS Care 2015; 27: 198– 205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. South Africa Department of Labour. . Compensation for Occupational Injuries and Diseases, Act No. 55 of 1993. Pretoria, South Africa: South Africa Department of Labour, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Von Delft A, Dramowski A, Khosa C, . et al. Why healthcare workers are sick of TB. Int J Infect Dis 2014; 32: 147– 151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. O'Donnell M, Jarand J, Loveday M, . et al. High incidence of hospital admissions with multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis among South African health care workers. Ann Intern Med 2010; 153: 516– 522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. South Africa Department of Labour. . Regulations for Hazardous Biological Agents. Pretoria, South Africa: Department of Labour, 2001. http://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/natlex4.detail?p_lang=en&p_isn=61275 Accessed November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 24. South Africa Department of Labour. . Occupational Health and Safety Act, No. 85. Pretoria, South Africa: Department of Labour, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Engelbrecht M C, van Rensburg A J.. Tuberculosis infection control practices in primary healthcare facilities in three districts of South Africa. South Afr J Epidemiol Infect 2013; 28: 221– 226. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Seale H, Leem J, Gallard J, Kaur R, Chughtai AA, Tashani M.. ‘The cookie monster muffler’: perceptions and behaviours of hospital healthcare workers around the use of masks and respirators in the hospital setting. Int J Infect Control 2014; 11: 1. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bryce E, Forrester L, Scharf S, Eshghpour. . What do healthcare workers think? A survey of facial protection equipment user preferences. J Hosp Infect 2008; 68: 241– 247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]