Abstract

Aims:

The role of arts and music in supporting subjective wellbeing (SWB) is increasingly recognised. Robust evidence is needed to support policy and practice. This article reports on the first of four reviews of Culture, Sport and Wellbeing (CSW) commissioned by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC)-funded What Works Centre for Wellbeing (https://whatworkswellbeing.org/).

Objective:

To identify SWB outcomes for music and singing in adults.

Methods:

Comprehensive literature searches were conducted in PsychInfo, Medline, ERIC, Arts and Humanities, Social Science and Science Citation Indexes, Scopus, PILOTS and CINAHL databases. From 5,397 records identified, 61 relevant records were assessed using GRADE and CERQual schema.

Results:

A wide range of wellbeing measures was used, with no consistency in how SWB was measured across the studies. A wide range of activities was reported, most commonly music listening and regular group singing. Music has been associated with reduced anxiety in young adults, enhanced mood and purpose in adults and mental wellbeing, quality of life, self-awareness and coping in people with diagnosed health conditions. Music and singing have been shown to be effective in enhancing morale and reducing risk of depression in older people. Few studies address SWB in people with dementia. While there are a few studies of music with marginalised communities, participants in community choirs tend to be female, white and relatively well educated. Research challenges include recruiting participants with baseline wellbeing scores that are low enough to record any significant or noteworthy change following a music or singing intervention.

Conclusions:

There is reliable evidence for positive effects of music and singing on wellbeing in adults. There remains a need for research with sub-groups who are at greater risk of lower levels of wellbeing, and on the processes by which wellbeing outcomes are, or are not, achieved.

Keywords: music, singing, systematic review, wellbeing, depression, older people

Introduction

Policy makers have acknowledged the importance and complexity of subjective wellbeing (SWB).1–4 Since 2011, SWB (satisfaction with life, worthwhileness, happiness and anxiety) has been included in UK population surveys conducted by the Office of National Statistics (ONS). Links between cultural activities and wellbeing are acknowledged,5 with cultural engagement embedded in national-level data collection,6 and recognised in public health programmes.7,8 However, SWB is a complex conceptualisation of mental states that includes hedonic dimensions (both positive and negative feelings such as happiness, anxiety and stress) and eudaemonic dimensions (such as meaningfulness, purpose and worthwhileness).9 Increased understanding of the effects of cultural interventions on these dimensions of SWB is needed in order to inform policy and programme development.

The Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC)-funded What Works Centre for Wellbeing has commissioned evidence reviews in key areas, one of which is Culture, Sport and Wellbeing (CSW). Following consultation with stakeholders,4 the CSW review team identified four topics to be addressed between 2015 and 2018. The first topic, music in adults, is reported here. Music is a complex intervention encompassing diverse forms, including singing, music listening and playing instruments. It also includes different genres, such as choral music, rock and pop. An increasing body of evidence has examined health outcomes from music, particularly from singing.10–12 This review sought to examine a wide range of music interventions that might be linked with SWB rather than health and to differentiate which intervention types may be more closely linked with wellbeing.

Methods

This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines.13 The review question was ‘What are the wellbeing outcomes of music and singing for adults and what are the processes by which wellbeing outcomes are achieved?’ The review anticipated that quantitative studies may report wellbeing outcomes, and these are reported here. Qualitative studies were included to illuminate the underlying processes by which wellbeing outcomes may be achieved; however, we decided to report the findings from the qualitative studies separately in order to be able to more fully examine the results from all the studies in the light of their respective methodologies.14,15

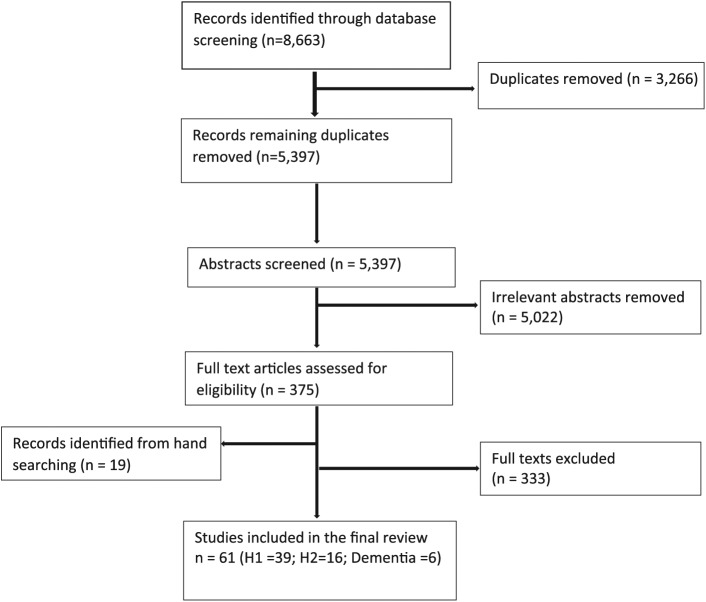

The search strategy encompassed the period 1996–2016 and the following electronic databases: PsychInfo, Ovid MEDLINE, ERIC, Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Web of Science), Social Science Citation Index (Web of Science), Science Citation Index, Scopus, PILOTS and CINAHL. Search terms were developed in an iterative process involving a number of trial searches. Searches used a combination of controlled vocabulary (MeSH) and free-text terms (Figure 1). We also checked the reference lists of published papers to identify additional relevant articles. The protocol was registered on the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (Registration number CRD42016038868).

Figure 1.

Search Strategy (Ovid MEDLINE)

Empirical studies in any language from countries economically similar to the United Kingdom were eligible if they assessed the relationship between individual or group music interventions and any recognised measure of SWB (not necessarily as the primary outcome) with adults. Regarding quantitative studies, we only included those with a concurrent comparator (CC). We excluded studies where the research subjects were paid professionals and where music was used for clinical purposes, such as pain management or symptom relief. However, music therapy interventions that sought to deliver wellbeing outcomes were included. Searching, screening and data extraction using standardised forms were undertaken by two reviewers, and discrepancies were resolved by deliberation, with a third researcher available for arbitration although this was not needed. GRADE and CERQual quality assessment schema were used to judge certainty/quality of evidence.16 A summary of the characteristics of included studies is provided in Table 1 (supplementary material).

Despite a great deal of heterogeneity across the studies, it was possible to undertake an exploratory meta-analysis on the effects of music interventions on anxiety and depression (see below).

Results

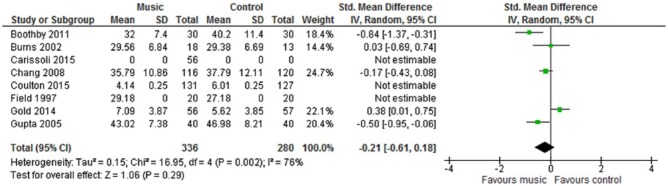

The electronic searches returned 5,397 records (Figure 2), with 61 relevant studies remaining after abstract screening and full-text review. These studies fell broadly into studies with healthy (H1) populations (39) and 22 studies of participants with diagnosed conditions (H2), including six studies of SWB in people with dementia.

Figure 2.

Literature search flow chart

Characteristics of quantitative studies included in the review

Study characteristics of quantitative studies, including study size, participants, wellbeing measures, outcomes and quality assessment are described in Table 1 (supplementary material). Many wellbeing measures were used, including anxiety, depression, mood and quality of life. While there was no consistency in how wellbeing was measured across the studies, there was a greater emphasis on negative dimensions than on positive dimensions of wellbeing.

Many activities were reported, most commonly music listening and regular group singing. The data show that some projects, such as community choirs, seem more likely to be attended by women than men. Where ethnic backgrounds and other demographic characteristics of participants were recorded, most participants were white and relatively well educated. However, several interventions were aimed specifically at other groups including males, marginalised groups including migrants and people in justice settings.

The review includes a wide range of study designs from many countries. Sample sizes for quantitative studies ranged from nine to 750. Risk of bias may have arisen from methodological challenges including, in quantitative studies, recruitment, randomisation, small sample sizes, attrition and prevalence of single-site studies in specific contexts.

Discussion

Discussion of quantitative findings

Given the heterogeneity of studies, we have concentrated on different population groups across the adult life span including students, targeted adult populations, and older adults.

Students

Ten quantitative studies in educational settings mostly examined brief (5–10 min) music listening interventions, often with a focus, such as listening to music during exercise (see Table 1, supplementary material). There were several randomised control trials (RCTs) but these tended to be small, single studies with less than 20 participants allocated to each group. A study of mostly male PE students reported reduced scores on the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory following listening to music during a brief treadmill running test,19 and a non-random study reported improvements in anxiety but not in enjoyment for nine male PE students undertaking a similar intervention.17 A study of mostly female students compared four small group conditions and reported improved mood and reduced negative affect for music and dancing, although cycling and sitting had no reported effects.25 Another study of male and female students compared four music listening, art and control conditions, reporting improved scores on the STAI-S and the Profile of Mood States (POMS) following music listening.23

A longer (30 min) listening activity was examined in a study comparing four conditions, reporting higher relaxation scores for own choice and classical music compared with hard rock and silence.24 In this study, anxiety scores for all groups except for the hard rock group significantly decreased. A longer study of 80 male students compared listening to slow-paced Indian instrumental music with silence for 30 min daily for 20 days, reporting a significant reduction of 2.7 points on the STAI for the intervention group as well as improvements in mood, while no significant changes were reported for the control group.40

Few of these H1 studies examined interventions other than music listening. However, one non-random study of students compared 30-min sessions of solo singing, group singing and swimming, reporting improvements in mood for all student groups, with the strongest changes reported for swimming.52 A musical presentation (MP) activity, in which participants in a group present themselves using music of their choice, was linked with enhanced sense of purpose and self-consciousness in a quasi-experimental study of female students.22

Only one study in this group examined playing musical instruments. This RCT of 154 non-musicians that compared a brief session of playing percussion to joyful music with simulated playing to computer-generated tones reported significant improvements in elements of the POMS, with depression, anxiety and fatigue decreasing in the music group but not in the control group. The music group also showed increased vigour, which decreased in the control group, while irritability increased in the control group but not in the music group.43

In addition to these studies of healthy student volunteers, two H2 studies examined the effects of music interventions for students with diagnosed depression. A study of 80 nursing students comparing a 10-week programme of listening to recorded Chinese music with usual activity reported significant improvements in depression.31 A small study of male and female students compared a 10-week music therapy programme with no music therapy, reporting improvements in anxiety and depression in the music group compared with controls.55

General adult populations

Nine studies assessed music in healthy general adult populations, including four studies in prisons. Five of the nine assessed brief listening interventions. A repeat-measure study of 100 hospital employees compared a music listening session with music and visual imagery, massage therapy and social support, reporting improvements on STAI and POMS for all groups.37 A comparison of daily music listening over 18 days with mindfulness meditation in a study of 56 adult employees reports no significant reductions in stress, although the stress in the waiting list control group increased.26 Two larger studies of pregnant women compared listening to relaxing music for 30 min a day for two weeks with usual activity. In both, music was associated with significant reductions in stress, anxiety and depression compared with the control condition.29,30 A quasi-experimental study of adult prisoners compared three weeks of listening to relaxing background music with no exposure, reporting reduced anxiety and improvements in anger after music listening.21

Studies with offender populations addressed music making as well as music listening. A non-random study of young offenders compared a 10-week programme of music making, including songwriting, playing and performing, with art or educational activities, reporting increased self-esteem in the music and education groups and improvements in emotional state for music and arts.18 A study of music therapy in which prisoners played instruments, sang and recorded music reported significant improvements in anxiety in the music group after two weeks; however, no data are available for the control group.38

There were two studies of choirs, one of which was a small non-random study with adult prisoners that compared nine weeks of group singing leading to a performance with usual activity, reporting no differences between groups in overall wellbeing scores, although participants in a choir involving volunteers from the community showed improvements in sociability, joviality, emotional stability and happiness compared with controls.33 Another open-access community-based choir study with healthy volunteers reported an increase in positive feelings after seven weeks of group singing but not after a comparator chatting activity, while negative feelings decreased significantly after singing but not after chatting.44

Healthy older adults

Seven studies with healthy adults were divided between music listening (3), singing (3) and music making (1). Three community-based studies of music listening in healthy older adults indicate an association between music listening and wellbeing. Two studies compared listening to music using headphones for 30 min a week for four weeks, reporting significant improvements in quality of life compared with controls45 and a 2-point reduction in mean Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) scores that was significant compared with controls.27 In another study, a difference of 2.79 points in GDS scores between intervention and control groups was reported after eight weeks of music listening.28

Wellbeing outcomes were identified in two larger studies of community singing for mostly female healthy older adults. One study of 258 participants over five sites compared a 14-week singing programme with usual activities, reporting significant differences between the groups on the York SF 12 mental health–related quality-of-life scale, and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) scale after three months, with significant differences in mental health–related quality of life in favour of group singing after six months.36 This research built on an earlier study of 166 participants that compared a 30-week choral singing project with usual activity. This showed significant differences after 12 months in morale, depression and loneliness for intervention groups compared with controls. While both groups evidenced a decline in morale and loneliness, this was slighter for the comparison group who showed a reduced risk of depression after 12 months.32 In contrast, a non-random community study evaluating community singing, music appreciation classes and music therapy for older adults over one academic year reported no significant wellbeing outcomes using an ad hoc questionnaire.49 Only one study of older adults examined playing musical instruments, reporting improvements in wellbeing both in older adults taking music lessons and those not taking lessons after 10 weeks.47

Music for targeted health populations

Eight quantitative studies examined music that was targeted at people with diagnosed health conditions. A non-random comparison of singing with usual care in 113 adults with a range of chronic conditions found that singing was associated with improvements in quality of life and positive affect.50 A study of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) compared weekly singing with attending a film club for eight weeks, reporting mental wellbeing improvements for both groups.46 Another study reported small improvements in anxiety, and significant improvements in depression, for a 4-week music therapy group for stroke patients compared with usual activity.42 Two small studies in palliative care settings examined brief (30 min) music therapy sessions, reporting improvements in wellbeing for a music therapy protocol compared with relaxation sessions,53 and in spirituality compared with no music therapy.54

The findings from studies of healthy older adults were not necessarily replicated in studies of adults with diagnosed health conditions or risk factors. For example, a study comparing the effects of music listening and relaxation on anxiety for older people with hypertension in a residential care setting reported no significant changes following 28 days of daily activity.20 Furthermore, a small study comparing twice weekly 30-min sessions of secular singing, religious singing and story-based reminiscence in a residential care setting reported no significant wellbeing outcomes after six weeks.41 A case-controlled study compared 15 months of tai chi, playing a musical instrument or singing in adults aged 51–85 years with risk factors for chronic disease, reporting improvements in resilience and depression for all intervention groups compared with controls, with the lowest depression rates for tai chi and dancing groups.51

Music and dementia

Challenges of researching SWB in people with dementia were apparent, and studies that measured SWB by proxy were excluded, leaving only three quantitative studies of music and wellbeing in dementia care that included a CC. Furthermore, a lack of specificity regarding diagnosis, and a tendency to include participants with relatively high baseline scores, makes it difficult to interpret these studies.56 One study compared group singing, listening and playing sessions with an interactive reading group, reporting no significant changes on the anxiety or on the Dementia Quality of Life Scale or the Geriatric Depression Scale.34,35 A five-centre study of 89 participants with dementia and their carers showed increased quality-of-life scores for a music listening group compared with usual activity, although the differences between the groups had levelled off by nine months.48 Evaluation of a 24-week individual music therapy intervention with 30 nursing home residents reported a significant reduction in anxiety and a 7.8 reduction in GDS scores, with no significant change reported for the control group; the differences in depression between the two groups were persistent at eight weeks post intervention.39

Exploratory meta-analysis

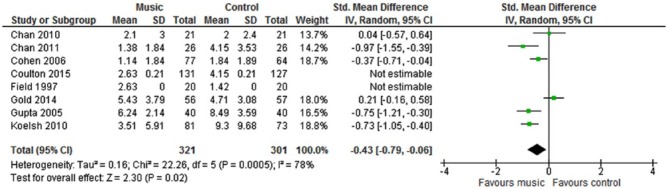

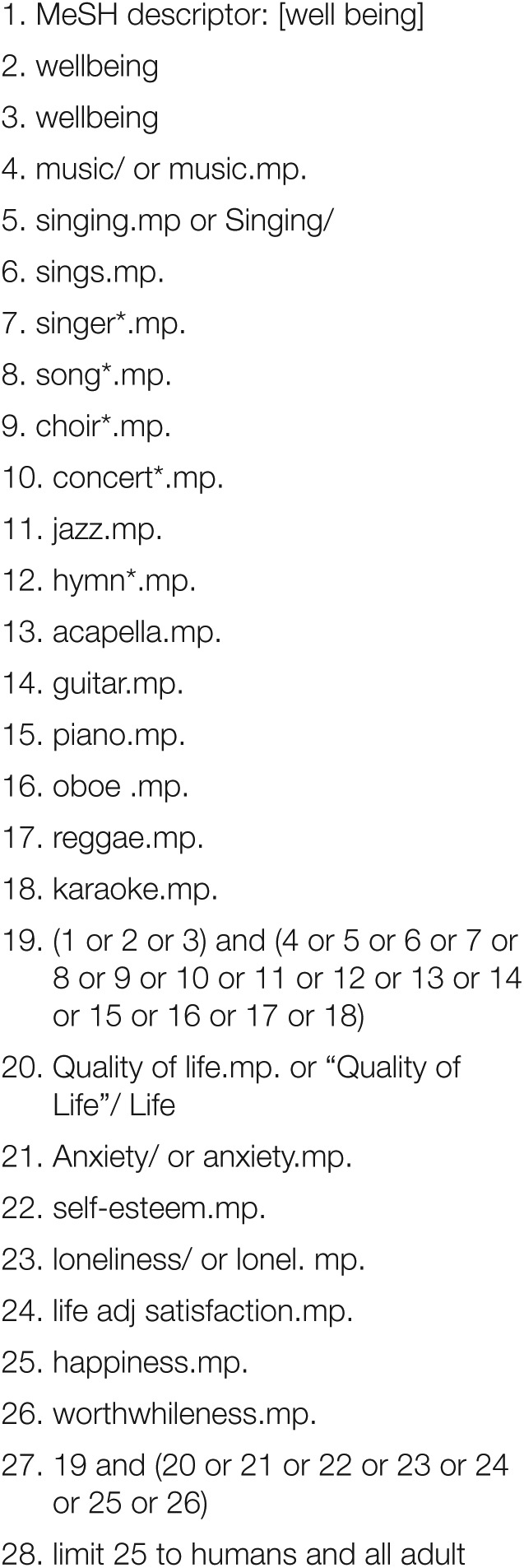

We tabulated characteristics and results of all included studies. Five studies contributed to the meta-analysis on anxiety and six studies contributed to the meta-analysis on depression (Figures 3 and 4). All outcomes were continuous measures. When standard errors, ranges or 95% confidence intervals were provided, standard deviations were calculated using standard formulae. Where no measure of spread was given, the study was still entered. We used Review Manager (version 5.3.5, Cochrane Library) for the meta-analyses. We used random-effects models because of heterogeneity of participants and interventions, although this approach only partly removes effects of heterogeneity.57 A variety of anxiety and depression outcome measurement scales were used in the studies, so we employed standardised mean differences (SMD) as the meta-analysis metric. There were insufficient studies reporting the same outcome to warrant risk of publication bias assessment by use of funnel plots.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of anxiety outcome results

Figure 4.

Forest plot of depression outcome results

The analysis showed that music had no statistically significant effect on anxiety (SMD −.21 (95% CI −.61 to +.18) but improved depression at follow up (–.43 (95% CI −.79 to −.06). Heterogeneity was high for both anxiety and depression, with I2 varying between 76% and 78%.

Quality of the evidence

Methodological strengths were noted in some areas, particularly in relation to research with older people. Common methodological limitations leading to risk of bias were identified (Table 1, supplementary material). There was a preponderance of small, single-site studies. Sampling issues and limitations regarding allocation to intervention and control groups were identified in several quantitative studies, some of which examined brief interventions and did not include longer term assessment. Longer term programmes reported risk of contamination affecting the control group or difficulties in controlling for confounding variables such as music listening practices, exercise or daily activities. In some studies, baseline conditions may not have been sufficiently pronounced to show a change in response to music. Nevertheless, approximately two-fifths of the evidence overall was graded moderate quality, with approximately one-sixth of studies graded high quality.

Limitations

The large number of hits following initial searches and the overlap between clinical and wellbeing interventions means that it is possible that some relevant evidence was not included in the review. However, our comprehensive search strategy, the pre-publication of our protocol on PROSPERO, dual screening and data extraction and independent quality assessment using GRADE and CERQual criteria ensured a rigorous process. Taking published studies as the sole evidence increases the potential risk of publication lag. However, a separate grey literature review included data from unpublished studies completed in the last three years.58

Conclusion

This article has discussed 37 quantitative studies of SWB outcomes for music and singing across the life course. Overall, music listening interventions seem to be the most frequently evaluated intervention, although group singing has also been the focus of a number of studies. Few studies have examined the effects of playing musical instruments, and further research is warranted in this area. Given the heterogeneity of studies, the diversity of interventions and the different intervention durations, it is difficult to generalise from them. A further difficulty is the overlap between clinical and non-clinical research, with some interventions that are described as music therapy seeming to have similar attributes to those that are not described in this way. Nevertheless, our exploratory meta-analysis suggests a positive association between music and improved depression.

Taken together, the studies broadly support the use of music and singing to enhance wellbeing and reduce or prevent depression in adults across the life span. For older adults, there is convincing evidence that regular participation in community music and singing activities can enhance and maintain wellbeing and prevent isolation, depression and mental ill health. There is also some evidence that targeted music and singing interventions can contribute to improved mood and reduced anxiety in specific groups including young adults, pregnant women and prisoners. Furthermore, interventions such as group singing may lead to improvements in wellbeing and quality of life for adults with a range of chronic conditions and in sensitive settings such as palliative care.

A key challenge may be recruiting from sub-groups who are at greater risk of lower levels of wellbeing. Future research may need to target participants with baseline wellbeing scores that are low enough to record any significant or noteworthy change following a music or singing intervention. There seems to be a tendency towards recruiting participants to community choirs who are female, white and relatively well educated. This is reinforced by supporting analysis of longitudinal data suggesting that engagement in music is positively correlated with younger age, White ethnicity and higher education level.9 Further research is needed to explore nuanced responses and to identify the individual, interpersonal and social factors, including gender, ethnicity and socioeconomic status that may mediate wellbeing outcomes in specific contexts. Addressing issues of context, social diversity and wellbeing inequalities represents an important focus point for policy, practice and research agendas on music singing and wellbeing.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: This work was supported by ESRC research grant ES/N003721/1 and forms part of the evidence review programme within the UK What Works Wellbeing Centre (https://whatworkswellbeing.org/). Ethical approval was obtained through Brunel University London’s research ethics committee (reference CHLS-RE41-14). There are no conflicts of interest to report.

Contributor Information

Norma Daykin, Centre for the Arts as Wellbeing, University of Winchester, Winchester SO22 4NR, UK.

Louise Mansfield, Doctor, Welfare, Health and Wellbeing, Institute for Environment, Health and Societies, Brunel University, London, Uxbridge, UK.

Catherine Meads, Professor, Anglia Ruskin University, Cambridge, UK.

Guy Julier, Professor, College of Arts and Humanities, University of Brighton, Brighton, UK.

Alan Tomlinson, Professor, College of Arts and Humanities, University of Brighton, Brighton, UK.

Annette Payne, Brunel University, London, Uxbridge, UK.

Lily Grigsby Duffy, Welfare, Health and Wellbeing, Institute for Environment, Health and Societies, Brunel University London, Uxbridge, UK.

Jack Lane, College of Arts and Humanities, University of Brighton, Brighton, UK.

Giorgia D’Innocenzo, Welfare, Health and Wellbeing, Institute for Environment, Health and Societies, Brunel University London, Uxbridge, UK.

Adele Burnett, Brunel University, London.

Tess Kay, Professor, Welfare, Health and Wellbeing, Institute for Environment, Health and Societies, Brunel University London, Uxbridge, UK.

Paul Dolan, London School of Economics and Political Science, London, UK.

Stefano Testoni, London School of Economics and Political Science, London, UK.

Christina Victor, Professor, Ageing Studies, Institute for Environment Health and Societies, Brunel University London, Uxbridge, UK.

References

- 1. Berry C. Wellbeing in four policy areas: Report by the all-party parliamentary group on wellbeing economics. Report, New Economics Foundation, London, September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2. O’Donnell G, Deaton A, Durand M, et al. Wellbeing and Policy. London: Legatum Institute, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dolan P, Metcalf R. Measuring subjective wellbeing: Recommendations on measures for use by national governments. Journal of Social Policy 2012; 41(2): 409–27. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Daykin N, Mansfield L, Payne A, et al. What works for wellbeing in culture and sport? Report of a DELPHI process to support coproduction and establish principles and parameters of an evidence review. Perspectives in Public Health 2017; 137: 281–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fujiwara D, MacKerron G. Arts council England: Cultural activities, artforms and wellbeing. Available online at: http://www.artscouncil.org.uk/sites/default/files/download-file/Cultural_activities_artforms_and_wellbeing.pdf (2015, Last accessed 2nd October 2017).

- 6. Fujiwara D, Kudrna L, Dolan P. Quantifying and valuing the wellbeing impacts of culture and sport. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/quantifying-and-valuing-the-wellbeing-impacts-of-culture-and-sport (2014, Last accessed 2nd October 2017).

- 7. Slay J, Ellis-Petersen M. The art of commissioning how commissioners can release the potential of the arts and cultural sector. New economics foundation. Available online at: https://www.ncvo.org.uk/practical-support/information/public-services/cultural-commissioning-programme (2016, Last accessed 2nd October 2017).

- 8. Daykin N, Joss T. Arts for health and wellbeing: An evaluation framework, Public Health England. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/arts-for-health-and-wellbeing-an-evaluation-framework 2016, (last accessed 2nd October 2017).

- 9. Dolan P, Testoni S. Assessing the relationships between engagement in music and subjective wellbeing. Supporting analysis. What Works Wellbeing, Culture, Sport and Wellbeing Evidence Review Programme. Available online at: https://www.whatworkswellbeing.org/product/supporting-analysis-music-singing-and-wellbeing/ 2016, (last accessed 28th October 2017).

- 10. Staricoff R. Arts in Health: A Review of the Medical Literature. London: Arts Council England, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Staricoff R, Clift S. Arts and music in healthcare: An overview of the medical literature: 2004–2011. London: Chelsea and Westminster Health Charity. Available online at: http://www.lahf.org.uk/sites/default/files/Chelsea%20and%20Westminster%20Literature%20Review%20Staricoff%20and%20Clift%20FINAL.pdf 2011, (last accessed 2nd October 2017).

- 12. Renton A, Phillips G, Daykin N, et al. Think of your art-eries: Arts participation, behavioural cardiovascular risk factors and mental well-being in deprived communities in London. Public Health 2012; 126: S57–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2009; 65: e1–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Daykin N, Julier G, Tomlinson A, et al. A systematic review of the wellbeing outcomes of music and singing in adults and the processes by which wellbeing outcomes are achieved. Volume 1: Music and singing interventions for healthy adults. Culture, Sport and Wellbeing Evidence Review Programme. What Works Centre, UK; Available online at: https://www.whatworkswellbeing.org/product/music-singing-and-healthy-adults/ (2016, Last accessed 28th October 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 15. Daykin N, Julier G, Tomlinson A, et al. A systematic review of the wellbeing outcomes of music and singing in adults and the processes by which wellbeing outcomes are achieved. Volume 2: Music and singing interventions for adults living with diagnosed conditions. Culture, Sport and Wellbeing Evidence Review Programme. What Works Centre, UK: Available online at: https://www.whatworkswellbeing.org/product/music-singing-and-adults-with-diagnosed-conditions/ 2016, (last accessed 28th October 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 16. Snape D, Meads C, Bagnall AM, et al. A guide to our evidence review methods. What works wellbeing. Available online at: https://whatworkswellbeing.files.wordpress.com/2016/02/what-works-wellbeing-methods-guide-july-2016.pdf (last accessed 28th October 2017).

- 17. Aloui A, Briki W, Baklouti H, et al. Listening to music during warming-up counteracts the negative effects of ramadan observance on short-term maximal performance. PLoS One 2015; 10(8): e0136400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Anderson K, Overy K. Engaging Scottish young offenders in education through music and art. International Journal of Community Music 2010; 3(1): 47–64. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Baldari C, Macone D, Bonavolontá V, et al. Effects of music during exercise in different training status. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness 2010; 50(3): 281–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bekiroğlu T, Ovayolu N, Ergün Y, et al. Effect of Turkish classical music on blood pressure: A randomized controlled trial in hypertensive elderly patients. Complementary Therapies in Medicine 2013; 21(3): 147–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bensimon M, Einat T, Gilboa A. The impact of relaxing music on prisoners’ levels of anxiety and anger. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 2015; 59(4): 406–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bensimon M, Gilboa A. The music of my life: The impact of the Musical Presentation on the sense of purpose in life and on self-consciousness. The Arts in Psychotherapy 2010; 37: 172–8. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Boothby DM, Robbins SJ. The effects of music listening and art production on negative mood: A randomized, controlled trial. The Arts in Psychotherapy 2011; 38: 204–8. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Burns JL, Labbé E, Arke B, et al. The effects of different types of music on perceived and physiological measures of stress. Journal of Music Therapy 2002; 39(2): 101–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Campion M, Levita L. Enhancing positive affect and divergent thinking abilities: Play some music and dance. Journal of Positive Psychology 2014; 9: 137–45. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Carissoli C, Villani D, Riva G. Does a meditation protocol supported by a mobile application help people reduce stress? Suggestions from a controlled pragmatic trial. Cyberpsychology, Behaviour and Social Networking; 2015. 2015; 18(1): 46–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chan MF, Chan EA, Mok E. Effects of music on depression and sleep quality in elderly people: A randomised controlled trial. Complementary Therapies in Medicine 2010; 18: 150–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chan MF, Wong ZY, Onishi H, et al. Effects of music on depression in older people: A randomised controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2012; 21: 776–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chang HC, Yu CH, Chen SY, et al. The effects of music listening on psychosocial stress and maternal–fetal attachment during pregnancy. Complementary Therapies in Medicine 2015; 23: 509–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chang MY, Chen CH, Huang KF. Effects of music therapy on psychological health of women during pregnancy. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2008; 17: 2580–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chen CJ, Sung HC, Lee MS, et al. The effects of Chinese five-element music therapy on nursing students with depressed mood. International Journal of Nursing Practice 2015; 21: 192–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cohen GD, Perlstein S, Chapline J, et al. The impact of professionally conducted cultural programs on the physical health, mental health, and social functioning of older adults. The Gerontologist 2016; 46: 726–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cohen ML. Choral singing and prison inmates: Influences of performing in a prison choir. Journal of Correctional Education 2009; 60(1): 52–65. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cooke M, Moyle W, Shum D, et al. A randomized controlled trial exploring the effect of music on quality of life and depression in older people with dementia. Journal of Health Psychology 2010; 15(5): 765–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cooke ML, Moyle W, Shum DH, et al. A randomized controlled trial exploring the effect of music on agitated behaviours and anxiety in older people with dementia. Aging and Mental Health 2010; 14(8): 905–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Coulton S, Clift S, Skingley S, Rodrigues J. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of community singing on mental health-related quality of life of older people: Randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry 2015; 207: 250–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Field T, Quintino O, Henteleff T, et al. Job stress reduction therapies. Alternative Therapies 1997; 3(4): 54–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gold C, Assmus J, Hjørnevik K, et al. Music therapy for prisoners pilot randomised controlled trial and implications for evaluating psychosocial interventions. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 2014; 58: 1520–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Guetin S, Portet F, Picot MC, et al. Effect of music therapy on anxiety and depression in patients with Alzheimer’s type dementia: Randomised, controlled study. Dementia and geriatric cognitive disorders 2009; 28(1): 36–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gupta U, Gupta B. Psychophysiological responsivity to Indian instrumental music. Psychology of music 2005; 33: 363–72. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Haslam C, Haslam SA, Ysseldyk R, et al. Social identification moderates cognitive health and wellbeing following story-and song-based reminiscence. Aging & Mental Health 2014; 18(4): 425–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kim DS, Park YG, Choi JH, et al. Effects of music therapy on mood in stroke patients. Yonsei Medical Journal 2011; 52(6): 977–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Koelsch S, Offermanns K, Franzke P. Music in the treatment of affective disorders: An exploratory investigation of a new method for music-therapeutic research. Music Perception: An Interdisciplinary Journal 2010; 27: 307–16. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kreutz G. Does singing facilitate social bonding? Music and Medicine 2014; 6(2): 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lee YY, Chan MF, Mok E. Effectiveness of music intervention on the quality of life of older people. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2010; 66: 2677–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lord VM, Hume VJ, Kelly JL. Singing classes for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Pulmonary Medicine 2012; 12(1):69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Perkins R, Williamon A. Learning to make music in older adulthood: A mixed-methods exploration of impacts on wellbeing. Psychology of Music 2014; 42(4): 550–67. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Särkämö T, Tervaniemi M, Laitinen S, et al. Cognitive, emotional, and social benefits of regular musical activities in early dementia: Randomized controlled study. The Gerontologist 2014; 54(4): 634–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Solé C, Mercadal-Brotons M, Gallego S, et al. Contributions of music to aging adults’ quality of life. Journal of Music Therapy 2010; 47(3): 264–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sun J, Buys N. Participatory community singing program to enhance quality of life and social and emotional wellbeing in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians with chronic diseases. International Journal on Disability and Human Development 2012; 12(3): 317–23. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sun J, Zhang N, Buys N, et al. The role of Tai Chi, cultural dancing, playing a musical instrument and singing in the prevention of chronic disease in Chinese older adults: A mind–body meditative approach. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2013; 15(4): 227–39. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Valentine E, Evans C. The effects of solo singing, choral singing and swimming on mood and physiological indices. British Journal of Medical Psychology 2001; 74: 115–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Warth M, Keßler J, Hillecke TK, et al. Music therapy in palliative care: A randomized controlled trial to evaluate effects on relaxation. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International 2015; 112(46): 788–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wlodarczyk N. The effect of music therapy on the spirituality of persons in an in-patient hospice unit as measured by self-report. Journal of Music Therapy 2007; 44(2):113–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wu SM. Effects of music therapy on anxiety, depression and self-esteem of undergraduates. Psychologia 2002; 2002(45): 104–14. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Victor C, Daykin N, Mansfield L, et al. A systematic review of the wellbeing outcomes of music and singing in adults and the processes by which wellbeing outcomes are achieved. Volume 3: Music, singing and wellbeing for adults living with dementia. Culture, Sport and Wellbeing Evidence Review Programme, What Works Centre, UK: Available online at: https://whatworkswellbeing.files.wordpress.com/2016/11/3-systematic-review-dementia-music-singing-wellbeing.pdf. 2016, (last accessed 28th October 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 57. Khan KS, Kunz R, Kleijnen J, et al. Systematic reviews to support evidence-based medicine, 2nd edn. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Daykin N, Julier G, Tomlinson A, et al. Review of the grey literature: Music, singing and wellbeing. Culture, Sport and Wellbeing Evidence Review Programme. What Works Centre, UK: 2016. https://whatworkswellbeing.files.wordpress.com/2016/11/grey-literature-review-music-singing-wellbeing-nov2016.pdf. Last accessed 28th October 2017. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.