Abstract

Background:

Breastfeeding supplies all the nutrients that infants need for their healthy development. Breastfeeding practice is multifactorial, and numerous variables influence mothers’ decisions and ability to breastfeed. This review identifies the factors potentially affecting the timely initiation of breastfeeding within an hour after birth and exclusive breastfeeding in the first 6 months in Middle Eastern countries.

Methods:

The Medline, ScienceDirect, and Web of Science databases were keyword-searched for primary studies meeting the following inclusion criteria: (1) publication in the English language between January 2001 and May 2017, (2) original research articles reporting primary data on the factors influencing the timely initiation of breastfeeding and/or exclusive breastfeeding, (3) the use of World Health Organization definitions, and (4) Middle Eastern research contexts. A random effect model was used to establish the average prevalence of the timely initiation of breastfeeding and exclusive breastfeeding in the Middle East.

Results:

The review identified 19 studies conducted in Saudi Arabia (7), Iran (3), Egypt (2), Turkey (2), Kuwait (1), the United Arab Emirates (1), Qatar (1), Lebanon (1), and Syria (1). The meta-analysis established that 34.3% (confidence interval [CI]: 20.2%-51.9%) of Middle Eastern newborns received breastfeeding initiated within an hour of birth, and only 20.5% (CI: 14.5%-28.2%) were fed only breast milk for the first 6 months. The 8 studies exploring breastfeeding initiation most commonly associated it with the following: delivery mode, maternal employment, rooming-in, and prelacteal feeding. The 17 studies investigating exclusive breastfeeding most frequently linked it to the following: maternal age, maternal education, maternal employment, and delivery mode.

Conclusions:

Middle Eastern health care organizations should fully understand all the determinants of breastfeeding identified by this review to provide suitable practical guidance and advice to help new mothers to overcome barriers where possible and to contribute to improving infant and maternal health in the region.

Keywords: breastfeeding, timely initiation, exclusive breastfeeding, risk factors, infants, Middle East

Introduction

Breastfeeding is a vital area of public health because it has a direct influence on the wider population’s overall quality of health and mortality levels.1–3 As well as being the key source of sufficient nutrition for breastfed infants, it offers well-known short-term benefits in lowering the risk of mortality and infectious diseases.2,4 Furthermore, breastfed infants have a lower chance of contracting allergic diseases5 and a lower risk of suffering sudden infant death syndrome.6 Prior studies have also confirmed the long-term protection breastfeeding offers against noncommunicable diseases.7–9 For these reasons, and on the basis of strong, long-established evidence, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) have both recommended that new mothers initiate breastfeeding within 1 hour of giving birth, then exclusively breastfeed their infants for the first 6 months of life, and continue breastfeeding up to the age of 2 years and beyond.10,11 Similarly, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has also recommended that infants should be exclusively breastfed for the first 6 months of life,12 and the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) has specified an optimal level of 6 months of exclusive breastfeeding with a delayed introduction of complementary foods until after the infant is at least 17 weeks old.13

Although the benefits of breastfeeding have been established beyond doubt by a large body of research, average breastfeeding rates in most countries remain below the global recommendations.2 A nationally representative survey in the United States which can be taken as an example found that only 16.8% of infants had been exclusively breastfed for 6 months.14 Similarly, Dop and Benbouzid15 reported a mean rate of 24% of infants exclusively breastfed at the age of 4 months in a combination of Middle Eastern countries and Pakistan, having combined data drawn from Lebanon (7%), Yemen (15%), Pakistan (16%), Jordan (32%), and Iran (48%). Breastfeeding practice is affected by a complicated combination of influencing factors such as family and maternal socio-demographics, biomedical factors, health care, psychosocial factors, the type and availability of social support, local community attitudes, and public policy.16–18 However, these factors do not exert a consistent influence when different cultures are compared. For example, it has been found that in developed countries, more highly educated women have a higher likelihood of initiating breastfeeding and of breastfeeding for longer than their less-educated peers, whereas in developing countries, the opposite is the case.19

Identifying and understanding breastfeeding’s determinants is necessary to support the planning of targeted interventions which aim to promote breastfeeding practice as well as in the wider design of national public health policy.20 However, to date, no review study has brought together the existing evidence on the factors encouraging or preventing the timely initiation and continuation of exclusive breastfeeding in the context of the Middle Eastern region. The present review therefore seeks to outline the factors associated in the past Middle Eastern research with timely breastfeeding initiation within the first hour of an infant’s life and with exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life.

Methods

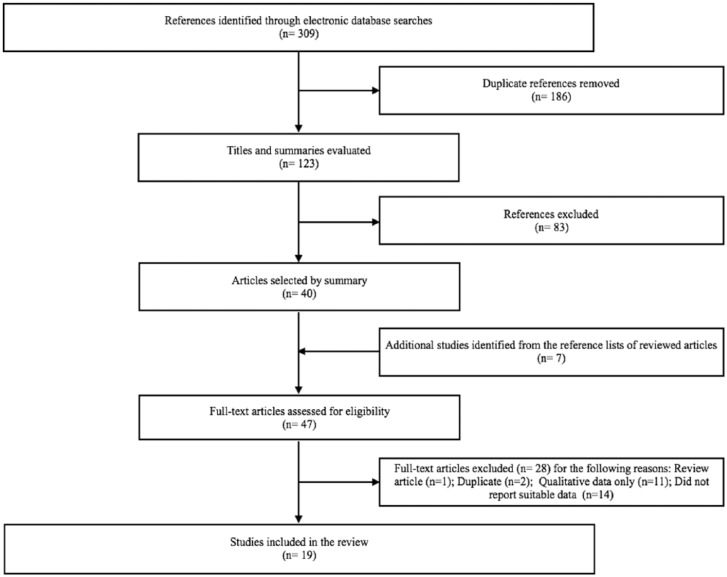

The Medline, ScienceDirect, and Web of Science databases were searched using the following keywords: “timely initiation” OR “delayed initiation” OR “first hour” OR “exclusive” AND “breastfeeding” OR “breast-feeding” OR “breast feeding” AND “factor(s)” OR “determinant(s).” When a study was deemed potentially relevant because it reported data on breastfeeding practices in a Middle Eastern country, the full text was obtained. The reference lists in the full texts were then used as further sources of possibly relevant studies. The PRISMA diagram (see Figure 1) illustrates the study selection process used in this review.21

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the present review’s search strategy.

The inclusion criteria for studies in this review were as follows: (1) publication in the English language between January 2001, when the last revision of the global breastfeeding recommendations occurred, and May 2017; (2) original research articles presenting primary data on the determinants of the timely initiation of breastfeeding and/or exclusive breastfeeding; (3) use of the WHO’s definitions, rather than any alternative definitions, of timely initiation and/or exclusive breastfeeding, which are as follows: the timely initiation of breastfeeding is defined as when a newborn infant is put to breast within the first hour of life22 and exclusive breastfeeding is defined as when an infant has only received breast milk (including expressed milk or milk from a wet nurse) to the exclusion of all other food or drink (including water) in the first 6 months of life23; and (4) Middle Eastern research contexts. Studies were excluded from the review if they matched any of the following criteria: (1) their primary focus was on the knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes of women toward the timely initiation of breastfeeding and/or exclusive breastfeeding; (2) neither the timely initiation of breastfeeding nor exclusive breastfeeding was treated as an outcome; and/or (3) they took a qualitative research approach.

Data extraction using a preestablished form was performed on the final sample to gather the following data: each study’s complete references, location (country/city), period of research, design, sample size, prevalence of breastfeeding reported, primary outcome measure and focus topic, variables analyzed, and results. Two tables were created and arranged alphabetically by the surname of the first author of each study based on the data extraction process, the first listing the studies which had examined the factors associated with the initiation of breastfeeding in the first hour after birth (Table 1), and the second listing the studies which had examined the factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life (Table 2). A forest plot was generated using the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software version 3.0 to estimate the prevalence in the Middle East of both the timely initiation of breastfeeding (Figure 2) and of exclusive breastfeeding (Figure 3).

Table 1.

Middle Eastern studies examining the factors associated with the timely initiation of breastfeeding within the first hour after birth.

| Authors | Year of publication | Place of publication | Period of study | Study design | Sample size, n | Age of the child at interview | Breastfeeding initiation rate, % | Statistical analysis | Factors evaluated with statistical significance | Factors evaluated without statistical significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Kohji et al24 | 2012 | Qatar | June-October, 2009 | Cross-sectional | 770 | <24 mo | 57 | χ2 | Maternal age (P = .021) Maternal employment (P = .009) No. of children (P = .02) Mode of delivery (P = .001) Advertisements for breast milk substitutes or teats (P < .001) Rooming-in (P < .001) |

Maternal nationality (P = .456) Maternal education (P = .503) Income (P = .087) Infant’s sex (P = .505) Planned method of feeding (P = .074) Maternal beliefs about colostrum (P = .926) Feeding advice during antenatal care (P = .394) Guidance on proper position during breastfeeding (P = .229) Birth facility (P = .808) Support for feeding problems after delivery (P = .229) |

| Batal et al25 | 2005 | Lebanon | More than 10 mo | Cross-sectional | 830 | 1-5 y | 18.3% within half an hour | Multivariate logistic regression | Mode of delivery (P = .000) Rooming-in (P = .000) Night feeding (P = .000) Mother-infant interaction (P = .000) |

Not reported |

| Dorgham et al26 | 2014 | Saudi Arabia (Taif) | 2013 | Cross-sectional | 400 | <6 mo | 22 | Multivariate logistic regression | Prelacteal feeding (OR = 12.02, P = .000) Maternal employment (OR = 5.559, P = .004) Father’s education (2 y education: OR = 6.99, P = .000; university: OR = 1.019, P = .968) Mode of delivery (OR = 7.195, P = .002) |

Not reported |

| El-Gilany et al27 | 2012 | Saudi Arabia (Al-Hasa) | June-July, 2009 | Cross-sectional | 906 | Within 2 wk of birth | 11.4 | Multivariate logistic regression | Place of residence (OR = 4.2, P < .001) Parity (2 or 3: OR = 2.9, P < .003; >4: OR = 2.4, P = .02) Prelacteal feeding (OR = 13.7, P < .001) Breast problems (OR = 3.4, P = .011) |

Maternal age (P > .05) Maternal education (P > .05) Maternal employment (P > .05) Income (P > .05) Infant’s sex (P > .05) Gestational age (P > .05) Birth weight (P > .05) Place of delivery (P > .05) Mode of delivery (P > .05) Admission to neonatal care unit (P > .05) Rooming-in (P > .05) |

| Haghighi and Taheri28 | 2015 | Iran (Shiraz) | January-June, 2015 | Cross-sectional | 257 | In the time of study for delivery | 63.8 | Multivariate logistic regression | Place of delivery (OR = 0.28, P = .011) Mode of delivery (OR = 21.6, P < .011) Previous history of breastfeeding (OR = 2.24, P = .033) Lack of hospitalization in the neonatal intensive care unit (OR = 0.03, P < .011) Prelacteal feeding (OR = 0.14, P = .016) |

Maternal education (< diploma: OR = 2.02, P = .171; university: OR = 2.36, P = .159) Gestational age (OR = 0.946, P = .402) |

| Radwan29 | 2013 | United Arab Emirates (Abu Dhabi, Dubai, and Al Ain) | Not reported | Cross-sectional | 587 | <24 mo | 19.4 | Binary logistic regression | Maternal employment (OR = 1.090, P = .011) Parity (OR = 2.26, P = .000) Mode of delivery (OR = 2.188, P = .001) Rooming-in (OR = 17.64, P = .000) Birth weight (2.5-3.0 kg: OR = 1.93; 3.1-4.0 kg: OR = 2.90; >4.0 kg: OR = 0.87, P = .011) |

Maternal age (25-30 y: OR = 0.98; 30-35 y: OR = 0.64; >35 y: OR = 0.68, P = .291) Maternal education (illiterate: OR = 2.17; primary: OR = 1.16; high school: OR = 1.43, P = .248) Infant’s sex (OR = 1.23, P = .898) |

| Yılmaz et al30 | 2017 | Turkey (Ankara) | March-October, 2015 | Cross-sectional | 341 | Not reported | 60.1 | Multivariate logistic regression | Planned pregnancy (OR = 2.019, P = .037) Mode of delivery (OR = 0.304, P < .001) |

Maternal age (P > .05) Maternal education (P > .05) Maternal employment (P > .05) Parity (P > .05) Health security (P > .05) Family structure (P > .05) Antepartum care (P > .05) Antepartum breastfeeding education (P > .05) Infant’s sex (P > .05) Birth weight (P > .05) |

| Yılmaz et al31 | 2016 | Turkey | July-December, 2015 | Cross-sectional | 200 | 6-24 mo | 45.5 | Multivariate logistic regression | Planned pregnancy (OR = 5.373, P = .005) Mode of delivery (OR = 48.332, P < .001) Infant’s sex (OR = 29.248, P < .001) |

Maternal age (OR = 0.967, P = .867) Maternal education (OR = 1.037, P = .943) Maternal employment (OR = 3.030, P = .103) Smoking status (OR = 1.111, P = .862) Breastfeeding education (OR = 2.330, P = .087) Gestational age (OR = 5.984, P = .058) Birth weight (OR = 0.607, P = .450) |

Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio.

Table 2.

Middle Eastern studies examining the factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months.

| Authors | Year of publication | Place of publication | Period of study | Study design | Sample size, n | Age of the child at interview | Breastfeeding initiation rate, % | Statistical analysis | Factors evaluated with statistical significance | Factors evaluated without statistical significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Akour et al32 | 2014 | Syria | July-October, 2012 | Cross-sectional | 334 | 0-12 mo | 12.9 | Binary logistic regression | Father’s education (OR = 2.595, P = .029) Smoking status (OR = 6.578, P = .002) Father’s advice (OR = 3.034, P = .027) Relatives’ advice (OR = 13.790, P = .007) |

Not reported |

| Al Ghwass et al33 | 2011 | Egypt (Al Der village) | January-June, 2010 | Cross-sectional | 1059 | 6-24 mo | 9.7 | Multivariate logistic regression | Infant’s sex (OR = 2.04, P = .002) Antenatal care visits (OR = 2.8, P < .001) Breastfeeding initiation (first hour: OR = 2.2, P = .018; 2-24 h: OR = 0.96, P = .026) Breastfeeding difficulty (OR = 1.8, P < .013) Maternal age (<20 y: OR = 2.9, P < .118; 20-30 y: OR = 2.03, P = .045) |

Maternal education (P > .05) Maternal employment (P > .05) Paternal education (P > .05) Social class (P > .05) Parity (P > .05) Last interdelivery (P > .05) Place of delivery (P > .05) Mode of delivery (P > .05) Birth weight (P > .05) Use of a pacifier (P > .05) |

| Al-Kohji et al24 | 2012 | Qatar | June-October, 2009 | Cross-sectional | 770 | <24 mo | 18.9 | χ2 | Maternal nationality (P < .001) Maternal employment (P = .001) Income (P = .012) Planned method of feeding (P = .003) Feeding patterns (P = .025) Advertisements for breast milk substitutes or teats (P = .005) |

Maternal age (P = .346) Maternal education (P = .462) No. of children (P = .351) Infant’s sex (P = .434) Mode of delivery (P = .269) Knowledge about exclusive breastfeeding (P = .066) Feeding advice during antenatal care (P = .351) Guidance on proper position during breastfeeding (P = .693) Birth facility (P = .162) Rooming-in (P > .99) Support for feeding problem after delivery (P = .222) |

| Alyouse et al34 | 2017 | Saudi Arabia (Riyadh) | February-March, 2015 | Cross-sectional | 322 | 6-24 mo | 13.7 | Multivariate logistic regression | Planned method of feeding (OR = 37.009, P < .001) Night feeding (OR = 0.298, P = .006) Previous history of breastfeeding (OR = 0.223, P < .019) |

Frequency of feeding (OR = 0.931, P = .54) |

| Alzaheb35 | 2017 | Saudi Arabia (Tabuk) | May-September, 2015 | Cross-sectional | 589 | 6-24 mo | 31.4 | Multivariate logistic regression | Maternal nationality (OR = 0.52, P = .039) Maternal employment (OR = 0.04, P = .001) Mode of delivery (OR = 0.53, P = .005) Knowledge about exclusive breastfeeding (OR = 2.21, P < .001) Birth weight (OR = 0.42, P = .011) |

Maternal age (<25 y: OR = 0.653, P = .128; 25-35 y: OR = 0.66, P = .084) Maternal education (OR = 1.04, P = .823) Living with partner (OR = 3.29, P = .118) Income (<5000 SR: OR = 1.03, P = .952; 5000-10 000 SR: OR = 0.75, P = .479; 10 001-15 000 SR: OR = 0.93, P = .859) No. of children (OR = 0.72, P = .081) Gestational age (OR = 0.75, P = .491) Infant’s sex (OR = 1.12, P = .534) |

| Amin et al17 | 2011 | Saudi Arabia (Al-Hasa) | Not reported | Cross-sectional | 641 | At 24 mo | 12.2 | Multivariate logistic regression | Maternal age (OR = 1.14, P = .034) Place of residence (OR = 1.74, P = .008) Maternal education (OR = 0.61, P = .026) Maternal employment (OR = 0.61, P = .010) No. of children (OR = 0.146, P = .035) Income (OR = 0.53, P = .020) |

Mode of delivery (OR = 0.78, P > .05) Oral hormonal contraception (OR = 0.95, P = .071) Breastfeeding initiation (OR = 0.84, P = .121) Infant’s sex (OR = 0.94, P > .05) Antenatal care visits (OR = 1.00, P > .05) Maternal illness (OR = 0.92, P = .163) |

| Batal et al25 | 2005 | Lebanon | More than 10 mo | Cross-sectional | 830 | 1-5 y | 10.1 | Multivariate logistic regression | Maternal education (OR = 2.2471, P = .034) Nonpregnancy weight (OR = 0.9502, P = .040) Maternal place of birth (OR = 0.9490, P = .012) Place of residence (OR = 0.3580, P = .006) No. of children (OR = 1.2397, P = .010) Painkiller use (OR = 0.8564, P = .040) Breastfeeding initiation (OR = 0.9502, P = .025) |

Not reported |

| Dashti et al19 | 2014 | Kuwait | October, 2007-October, 2008 | Prospective cohort study | 345 | 26 wk postpartum | 2 | Multivariate logistic regression | Maternal place of birth (other Arab countries: OR = 0.65; other non-Arab countries: OR = 0.93, P < .001) Maternal education (OR = 0.74, P = .030) Maternal employment within 6 mo postpartum (OR = 0.76, P = .022) Breastfeeding problems in hospital (OR = 0.80, P = .046) Breastfeeding on demand in hospital (OR = 1.28, P = .040) Infant’s father feeding preference (OR = 1.33, P = .045) |

Parity (OR = 0.63, P > .05) Use of a pacifier (<4 wk: OR = 1.66; at or after 4 wk: OR = 1.25, P > .05) Prelacteal feeding (OR = 0.59, P > .05) Maternal grandmother’s infant feeding preference (OR = 2.11, P > .05) |

| Dorgham et al26 | 2014 | Saudi Arabia (Taif) | 2013 | Cross-sectional | 400 | Up to 6 mo | 19 | Multivariate logistic regression | Maternal education (2 y education: OR = 10.270, P = .009; university: OR = 1.440, P = .233) Father’s education (2 y education: OR = 2.707, P = .193; university: OR = 0.596, P = .093) Mode of delivery (OR = 2.260, P = .019) Infant’s age (<1 mo: OR = 2.704, P = .000; 2-3 mo: OR = 4.759, P = .998) |

Not reported |

| El-Gilany et al36 | 2011 | Saudi Arabia (Al-Hasa) | June-July, 2009 | Cross-sectional | 1904 | At 6 mo | 24.4 | Multivariate logistic regression | Place of residence (OR = 2.2, P < .05) Maternal employment (OR = 4.7, P < .05) Birth weight (OR = 1.9, P < .05) Mode of delivery (OR = 1.7, P < .05) Prelacteal feeding (OR = 3.1, P < .05) Breastfeeding initiation (OR = 2.0, P < .05) Feeding patterns (OR = 3.4, P < .05) |

Maternal education (less than secondary: OR = 1.9, P > .05; secondary: OR = 2.1, P > .05) Income (OR = 0.9, P > .05) Maternal age (<20 y: OR = 1.1; 20-35 y: OR = 1.1, P > .05) Parity primipara: OR = 1.1; 2 and 3: OR = 1.1, P > .05) Infant’s sex (OR = 1.0, P > .05) Gestational age (OR = 0.5, P > .05) |

| El Shafei and Labib37 | 2014 | Egypt | February-May, 2012 | Cross-sectional | 187 | <24 mo | 29.9 | Multivariate logistic regression | Maternal age (OR = 3.4, P = .02) No. of children (OR = 0.3, P = .02) Health education about breastfeeding (OR = 9.4, P = .001) Knowledge about breastfeeding (OR = 2.2, P = .005) |

Maternal education (OR = 1.5, P = .44) Maternal employment (OR = 1.4, P = .31) Antenatal care visits (OR = 1.0, P = .90) Pregnancy-related problems (OR = 1.5, P = .40) History of contraception (OR = 1.8, P = .10) Mode of delivery (OR = 1.056, P = .80) Infant’s sex (OR = 14, P = .30) Lactational problems (OR = 0.8, P = .60) |

| Mahfouz et al38 | 2014 | Saudi Arabia (Jazan) | November, 2012 | Cross-sectional | 400 | <5 y | 26.9 | Multivariate logistic regression | None | Infant’s sex (OR = 1.27, P = .313) Maternal age (25-34 y: OR = 1.80, P = .050; more than 35 y: OR = 1.25, P = .413) Maternal education (OR = 1.01, P = .984) Maternal employment (OR = 1.01, P = .960) Place of residence (OR = 1.23, P = .495) Parity (2-4 children: OR = 1.49, P = .277; more than 4: OR = 0.85, P = .606) Use of contraception (OR = 1.03, P = .925) |

| Noughabi et al39 | 2014 | Iran (Tehran) | June-July, 2011 | Cross-sectional | 538 | 6-24 mo | 46.5 | Infant put to the breast (0-5 min: OR = 1.76; 6-30 min: OR = 2.35; 30 min to 2 h: OR = 1.89; 2-12 h: OR = 1.37, P < .05) Mother’s intention to breastfeed before childbirth (OR = 5.85, P < .05) Formula supplementation at hospital after birth (OR = 0.41, P < .05) Mother receiving conflicting feeding advice (OR = 0.53, P < .05) |

Maternal age (P > .05) Maternal education (P > .05) Maternal employment (P > .05) Maternal ethnicity (P > .05) Mother’s return to work after delivery (P > .05) Parity (P > .05) Father’s age (P > .05) Father’s education (P > .05) Father’s employment (P > .05) Father’s ethnicity (P > .05) Income (P > .05) Place of residence (P > .05) Mode of delivery (P > .05) Infant’s sex (P > .05) Birth weight (P > .05) Infant’s birth age (P > .05) Infant’s birth health (P > .05) Health problems in the 6 mo after delivery (P > .05) Postnatal depression (P > .05) Antenatal care visits (P > .05) Skin to skin contact (P > .05) |

|

| Breastfeeding on demand (P > .05) Clinician help with breastfeeding (P > .05) Clinician counseling on breastfeeding (P > .05) Husband’s support of breastfeeding (P > .05) Family and friends’ support of breastfeeding (P > .05) Use of a pacifier (P > .05) Enough time for breastfeeding (P > .05) Previous breastfeeding (P > .05) |

||||||||||

| Radwan29 | 2013 | United Arab Emirates (Abu Dhabi, Dubai, and Al Ain) | Not reported | Cross-sectional | 587 | <24 mo | 25 | Binary logistic regression | Maternal education (illiterate: OR = 2.12; primary: OR = 2.12; high school: OR = 1.90, P = .010) Maternal employment (OR = 1.89, P = .009) Parity (OR = 1.83, P = .002) Mode of delivery (OR = 2.20, P = .001) Rooming-in (OR = 5.87, P = .000) Night feeding (1-3 times: OR = 1.97; 4-6 times: OR = 2.19, P = .006) Frequency of feeding (OR = 2.76, P = .006) |

Infant’s sex (OR = 0.69, P = .058) Maternal age (26-30 y: OR = 0.91; 30-35 y: OR = 1.66; >35 y: OR = 1.43, P = .099) Nipple problems (OR = 1.41, P = .072) Use of contraception (none-hormonal: OR = 1.18; hormonal: OR = 0.83, P = .262) |

| Vafaee et al40 | 2010 | Iran (Mashhad) | 2007 | Cross-sectional | 1450 | 7-12 mo | 56.4 | Binary logistic regression | Maternal age (21-25 y: OR = 0.620, P = .203; 26-30 y: OR = 0.560, P = .082; 31-35 y: OR = 0.630, P = .158; 35-40 y: OR = 0.430, P = .031) Knowledge about breastfeeding (OR = 1.700, P = .002) Relatives’ advice (OR = 1.700, P = .011) |

Maternal education (elementary school; OR = 0.210, P = .01; guidance school: OR = 0.310, P = .023; high school: OR = 0.190, P = .004; university: OR = 0.160, P = .005) Maternal chronic illness (OR = 0.064, P = .103) Frequency of feeding (none: OR = 0.500, P = .018; afternoon; OR = 1.190, P = .700; night: OR = 0.770, P = .330; midnight: OR = 0.890, P = .500) |

| Yılmaz et al30 | 2017 | Turkey | March-October, 2015 | Cross-sectional | 329 | Not reported | 38.9 | Multivariate logistic regression | Antepartum breastfeeding education (OR = 7.172, P < .001) | Maternal age (P > .05) Maternal education (P > .05) Father’s education (P > .05) Father’s employment (P > .05) Health security (P > .05) Planned pregnancy (P > .05) Antenatal care visits (P > .05) Frequency of feeding (P > .05) Night breastfeeds (P > .05) Nipple problems (P > .05) Use of a pacifier/bottle (P > .05) Maternal employment within 6 mo postpartum (P > .05) Parity (P > .05) Family structure (P > .05) Social support (P > .05) Mode of delivery (P > .05) Infant’s sex (P > .05) Birth weight (P > .05) |

| Yılmaz et al31 | 2016 | Turkey | July-December, 2015 | Cross-sectional | 200 | 6-24 mo | Not reported | Maternal age (OR = 2.451, P = .040) Planned pregnancy (OR = 2.495, P = .046) Postpartum education (OR = 2.782, P = .031) Nipple problems (OR = 5.984, P = .058) Night feeding (OR = 3.142, P = .001) Formula initiation (OR = 37.790, P = .001) |

Maternal education (OR = 1.159, P = .775) Maternal employment (OR = 3.731, P = .235) Mode of delivery (OR = 1.825, P = .167) Infant’s sex (OR = 0.615, P = .268) |

Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio.

Seventeen studies identified as exploring the factors associated with the practice of exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months of age in a Middle Eastern context: 6 were conducted in Saudi Arabia17,26,34–36,38; 2 each in Turkey,30,31 Egypt,33,37 and Iran39,40; and 1 each in Kuwait,19 the United Arab Emirates,29 Qatar,24 Lebanon,25 and Syria.32

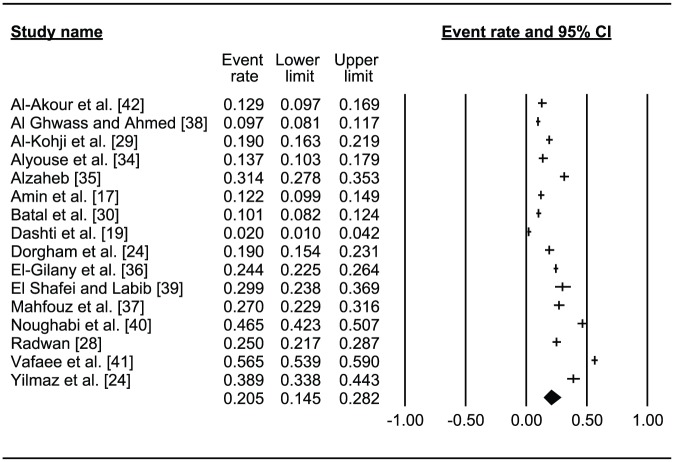

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the pooled prevalence of the timely initiation of breastfeeding within the first hour after birth in the Middle East region. 95% CI indicates 95% confidence interval.

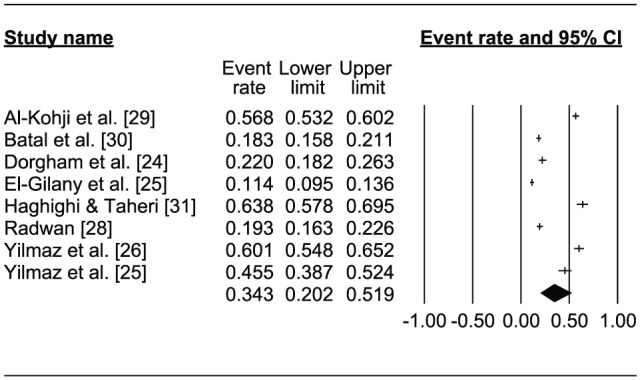

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the pooled prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months in the Middle East region. 95% CI indicates 95% confidence interval.

Results

A total of 19 studies were included in the final analysis, with the following country breakdown: Saudi Arabia (7), Iran (3), Egypt (2), Turkey (2), Kuwait (1), the United Arab Emirates (1), Qatar (1), Lebanon (1), and Syria (1).

Timely initiation of breastfeeding

Table 1 lists the 8 studies identified as exploring the factors associated with the initiation of breastfeeding in the first hour after birth in a Middle Eastern context. Two were conducted in Saudi Arabia,26,27 2 in Turkey,30,31 and 1 each in the United Arab Emirates,29 Qatar,24 Lebanon,25 and Iran.28 All were cross-sectional studies, and their sample sizes ranged between 200 and 906. The age ranges of the sampled infants at the time of interview (and, thus, the length of recall in each study) varied widely, between immediately after delivery and children aged up to 5 years.

Timely initiation of breastfeeding rates

The studies reported a wide-ranging prevalence of breastfeeding in the first hour of life, the lowest rate being 11.4% in a province of Saudi Arabia,27 and the highest 63.8% in Iran.28 The combined results of the 8 studies revealed the pooled prevalence of timely initiation of breastfeeding in the Middle Eastern region to be 34.3% (confidence interval [CI]: 20.2%-51.9%; Figure 2).

Factors associated with the timely initiation of breastfeeding

Mode of delivery

Of the 8 studies, 7 studies which investigated the association between mode of delivery and timely breastfeeding initiation established that caesarean section deliveries are a risk factor inhibiting the initiation of breastfeeding within the first hour of life.24–26,28–31 Delivery by caesarean section was therefore identified as a significant barrier to the initiation of breastfeeding within the first hour of life.

Maternal employment

Of the 8 studies, 6 studies identified by this review explored the relationship between the mother’s employment status and the timely initiation of breastfeeding, and 3 of those 6 identified a statistically significant association.24,26,29 More specifically, those 3 found that a higher proportion of working mothers than nonworking mothers delayed the initiation of breastfeeding for more than an hour after birth.

Rooming-in

The WHO defines rooming-in care as a mother staying in the same room night and day with her newborn infant, without any limit on the direct contact between them.41 A positive association between rooming-in care and timely breastfeeding initiation within the first hour after giving birth was observed by 3 of the 4 studies which explored the relationship between the two.24,25,29

Parity

Of the 8 papers, 3 papers identified in this review as examining the possible relationship between parity and breastfeeding initiation found a positive association between greater parity and timely breastfeeding initiation in the first hour after giving birth.27,29,30 For example, a study in the United Arab Emirates found that multiparous mothers had more than double (2.3 times) the likelihood of starting to breastfeed within the first hour of life than primiparous mothers.29

Prelacteal feeding

Prelacteal feeding involves food or drink other than human breast milk being given to newborns prior to breastfeeding initiation.42 Three of the studies included in the present review examined the impact of prelacteal feeding on timely breastfeeding initiation,26–28 and they all agreed that feeding a newborn infant prelacteal food may be associated with the delayed initiation of breastfeeding to beyond an hour after birth.

Other factors

Several additional factors influencing timely breastfeeding initiation within the first hour of life have also been explored by prior studies in Middle Eastern countries, including place of residence, place of delivery, pregnancy planning, previous breastfeeding history, paternal education level, infant’s sex, infant’s birth weight, advertisements for breast milk substitutes or teats, and night feeding. However, although these factors received little attention in terms of their effects on timely breastfeeding initiation across the 8 studies, as usual only 1 paper examined each of them; their limited investigation does not necessarily imply that they are unimportant.

Exclusive breastfeeding

Table 2 lists the 17 studies which explored the factors linked to the practice of exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months of age in a Middle Eastern context. In all, 6 were conducted in Saudi Arabia17,26,34–36,38; 2 each in Turkey,30,31 Egypt,33,37 and Iran39,40; and 1 each in Kuwait,19 the United Arab Emirates,29 Qatar,24 Lebanon,25 and Syria.32 All except one (16 in total) were cross-sectional surveys, the other being a prospective cohort design. The maximum ages of the children in their samples ranged between 6 months and 5 years at the time of the interviews. The smallest study sample consisted of 200 participants, and the largest sample contained 1904 participants.

Exclusive breastfeeding rates

The reported prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months widely ranged from a low of 2% in Kuwait19 to a high of 56.4% in Iran.40 The combined results of 17 studies revealed that the pooled prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months in the Middle Eastern region was 20.5% (CI: 14.5%-28.2%; Figure 3).

Factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding

Maternal education

The factor most commonly examined by the identified papers was the level of maternal education, which 15 of the 17 studies explored in relation to its possible association with exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of an infant’s life. However, these studies reached inconsistent conclusions; specifically, 2 reported a significant positive association,19,26 whereas 3 found a significant negative association,17,25,29 and the remaining 10 established no association in either direction.24,30,31,33,35-40

Maternal employment

Most (12) of the 17 identified studies explored the possible link between maternal employment and exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life, and 7 of these 12 reported a statistically significant association between the two.17,19,24,29,30,35,36 More specifically, 6 of the studies (3 of which were performed in Saudi Arabia, with the others performed in Kuwait, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates, respectively) concluded that mothers who were formally employed or working outside their homes were less likely to exclusively breastfeed at 6 months.17,19,24,29,30,35,36 The remaining study among the 7 which found an association reported the opposite conclusion among a sample of Turkish mothers, finding a positive association between exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months and maternal employment.30

Maternal age

A total of 12 studies explored the impact of maternal age on exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of the infant’s life. Seven found no statistically significant association between maternal age and exclusive breastfeeding.24,29,30,35,36,38,39 However, the remaining 5 reported a statistically significant association between the two and found that intermediate ages have a raised likelihood of exclusive breastfeeding.17,31,33,37,40

Mode of delivery

Similarly, 12 of the 17 studies explored the possible association between the mode of delivery and exclusive breastfeeding, and 4 of them found a statistically significant link between caesarean births and lower exclusive breastfeeding rates at 6 months of age.26,29,35,36 For instance, a recent study in Saudi Arabia reported an inverse association between caesarean section delivery and exclusive breastfeeding.35

Other factors

Associations were found by 3 different studies between exclusive breastfeeding and the following factors: number of children,17,25,37 place of residence,17,25,36 night feeding,39,31,34 breastfeeding initiation,25,33,36 and maternal knowledge of exclusive breastfeeding.35,37,40 Furthermore, 2 different studies associated the following factors with exclusive breastfeeding practice: total family income,17,24 maternal birthplace,19,25 paternal education level,26,32 maternal nationality,24,35 planned feeding method,25,34 birth weight,35,36 advertisements for breast milk substitutes or teats,34,39 prelacteal feeding,36,39 and advice from relatives.32,40 A single study associated exclusive breastfeeding with each of the following variables: the infant’s age,26 planned (rather than unplanned) pregnancy,31 rooming-in,29 the mother’s previous history of breastfeeding,34 antenatal care visits,33 the infant’s sex,33 and maternal smoking status.32 A few of the studies also explored the possible associations between other factors and exclusive breastfeeding, such as instances of maternal illness, mothers cohabiting with partners, contraceptive usage, gestational age, and pacifier use, but no significant associations were found with any of these factors.

Discussion

Despite the WHO’s 2 recommendations that (1) mothers should initiate breastfeeding of their newborn infants in the first hour of life and (2) infants should be exclusively breastfed until they reach 6 months of age,11 this study’s meta-analysis found that only 34.3% (CI: 20.2%-51.9%) of newborn infants in the Middle East received early initiated breastfeeding, and only 20.5% (CI: 14.5%-28.2%) exclusively received breast milk for the first 6 months of their lives. The WHO’s infant and young children feeding rates stipulate that 0% to 29% is a poor rate of early breastfeeding initiation, whereas 30% to 49% is considered fair, 50% to 89% good, and 90% to 100% very good; meanwhile, the WHO infant and young children feeding rate defines exclusive breastfeeding rates as follows: 0% to 11% is poor, 12% to 49% fair, 50% to 89% good, and 90% to 100% very good.43 The present review’s findings therefore indicate a generally fair prevalence of both the timely initiation of breastfeeding and of exclusive breastfeeding in the Middle East region. However, the respective rates which the present meta-analysis revealed for the Middle East region are each considerably below the global average, which for breastfeeding initiation within the first hour after birth is 45%44 and for exclusive breastfeeding of infants in the first 6 months of life is 41%.45 A deeper knowledge of the factors which influence the initiation and continuation of exclusive breastfeeding of newborn and young infants may support the planning of health strategies designed to boost rates of breastfeeding in line with the WHO’s recommendations. The present review has thus sought to identify the factors which may affect both timely breastfeeding initiation in the first hour of life and exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life in countries in the Middle East.

Timely breastfeeding initiation in the first hour after birth and exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life are each potentially affected by many factors, ranging from economic to sociocultural, and the direction and strength of their associations differ across different countries and over time.17,19 This review found that several factors could predict Middle Eastern mothers’ breastfeeding practices. Of these, delivery mode was one of the most widely investigated factors in the prior research, with 7 of the 8 previous studies investigating its association with timely breastfeeding initiation and 12 of the 17 studies investigating its association with exclusive breastfeeding. All 7 of the studies which investigated the association between the mode of delivery and timely breastfeeding initiation identified caesareans as a risk factor for failing to initiate breastfeeding in the first hour after birth,24–26,28–31 and caesarean delivery was also found to be a risk factor inhibiting exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life by 4 of the 12 studies which explored the possible link between delivery mode and exclusive breastfeeding.26,29,35,36 Caesarean section delivery has therefore been established as a significant potential barrier to the timely initiation and continuation of breastfeeding, most likely because infants born this way are usually moved straight away to a nursery so that their mother can rest and recover from her operation, meaning that the first breastfeed happens after more time has elapsed, and the onset of lactation is therefore significantly delayed, along with an increased chance of supplementation.19 Furthermore, even though the WHO advocates that the rate of caesarean deliveries should not exceed 10.0% to 15.0%,46 far higher levels were reported by most of the studies in the present review, ranging from the lowest level of 12.3%, found in Saudi Arabia,17 to the highest, 60.2%, in Iran.39 A clear need therefore exists for appropriate guidelines for caesarean deliveries to minimize delays in, and/or avoid the prevention of, the establishment of exclusive breastfeeding.

Another potential influencing factor which many of the studies examined was maternal employment; however, they reached no consensus regarding its effect. More specifically, 3 of the 6 studies that investigated the impact of maternal employment status on timely breastfeeding initiation found it to be a risk factor potentially delaying initiation,24,26,29 whereas 6 of the 12 studies17,19,24,29,35,36 that examined the possible association between maternal employment and exclusively breastfeeding for the first 6 months of an infant’s life found it to be a risk factor, and a single study found it to be a protection factor;30 the other 5 studies which investigated a possible link found no association. The negative association found in these prior studies between employment and breastfeeding practices may be universal for the simple reason that mothers who are able to spend enough time with their newborn and very young infants are more likely to exclusively breastfeed them easily than mothers who lack sufficient time in their daily schedules due to their jobs or for any other reasons.47 Moreover, working mothers in countries in the Middle East are generally only allowed 2 months of maternity leave on full pay by law, and breastfeeding facilities in their workplaces are often not available. It is therefore obvious why many working mothers may struggle to initiate and maintain exclusive breastfeeding, whereas mothers staying at home are less affected by some of the restricting factors. In contrast, the Turkish study in the present review established a positive association between maternal employment and exclusive breastfeeding, which the authors explained by observing that the higher exclusive breastfeeding rates they had found among working mothers had probably been caused by returning to work after spending the first 6 months with their infants at home, as mothers who usually work outside their homes and who can legally claim maternity leave usually have more ideal conditions to exclusively breastfeed during their leave from work.30 This finding means that improved, guaranteed maternity leave entitlement and increased flexibility in working terms and conditions would be likely to support improvements in breastfeeding rates across Middle Eastern countries.

Breastfeeding rates may also be linked to parity and maternal age.16 Regarding parity, all 3 of the studies that explored its possible association with timely breastfeeding initiation confirmed a positive relationship between higher parity and the likelihood of the timely initiation of breastfeeding27,29,30; meanwhile, a positive association between exclusive breastfeeding and parity was only reported by 2 of the 7 studies which had investigated the possible relationship between the two.29,30 Moving on, most studies in this review found no significant link between maternal age and either the timely initiation of breastfeeding (4 of the 5 which examined this factor found no association) or exclusive breastfeeding (7 of the 12 found no association). However, a minority of studies did find an association between breastfeeding practices and maternal age, and in these cases, mothers of intermediate ages seem to have had a higher likelihood of breastfeeding.17,31,33,37,40 As an example, an Egyptian study found that mothers in the 20 to 30 years age group had a significantly higher chance of breastfeeding exclusively for the first 6 months of their infant’s life, with an odds ratio of 2.9.33 A possible reason for this is that younger (teenage) mothers and those who are in the 35 years or older age group more often prematurely interrupt their breastfeeding.16

Maternal education was the most explored variable in the prior studies included in the review, as 6 of the 8 studies investigated its possible association with timely breastfeeding initiation and 15 of the 17 studies examined its potential link with exclusive breastfeeding. None of the 6 studies identified any significant association between maternal education level and the timely initiation of breastfeeding.24,27-31 However, varying results were found regarding its association with exclusive breastfeeding; 2 studies found a significant positive association,19,26 another 3 revealed a significant negative association,17,25,29 and the remaining 10 could not confirm an association in either direction.24,30,31,33,35-40 The authors of the 3 papers which did establish a negative association between exclusively breastfeeding for the first 6 months of an infant’s life and maternal education all offered the explanation that higher education is usually associated with more modern thinking in developing countries, thus possibly discouraging lifestyle practices deemed “traditional,” including breastfeeding.48 In contrast, one of the papers which observed a positive association offered the possible reason that more highly educated mothers are more likely to be aware of the health benefits of breastfeeding.49 The inconsistent results arising from the prior studies investigating the influence of various factors on breastfeeding practices mean that there is a definite need for further research to establish a clearer understanding of the association between potential risk factors and breastfeeding practices.

The present review has some limitations which should be discussed. First, although broad search strategies were deployed, the possibility of missing some prior studies which would have been relevant cannot be fully discounted. Second, only articles written in English were considered for inclusion in the present review. Third, almost all the studies included in the review were cross-sectional in design (18/19 = 94.7%), and this means they must be regarded as weak in determining causality as they are unable to guarantee a temporal cause-effect relationship. Fourth, there is a potential issue of information validity concerning the variables. Because data were gathered from mothers for up to 5 years after they gave birth, the risk of measurement error and recall bias is relatively high in many of the studies we reviewed. Fifth, some of the studies lacked a multivariate analysis and those that included it did not consistently use the same covariates for adjustment. Finally, this literature review only covers studies in Middle Eastern contexts, so its synthesized framework may not necessarily be applicable elsewhere in the world.

Conclusions

Overall, the rates of breastfeeding initiation and exclusivity reported by the reviewed studies’ samples of mothers in different Middle Eastern countries are significantly lower than the present WHO recommendations. Breastfeeding practice is shaped by various sociocultural and physiological factors which can impact, either alone or in combination, on a mother’s choice and ability to successfully initiate and maintain exclusive breastfeeding of her infant. The present review has found that the factors most frequently reported as influential on timely breastfeeding initiation in the first hour after giving birth were the mode of delivery, maternal employment, rooming-in, and prelacteal feeding. The review has also established that the factors most frequently associated with breastfeeding exclusively for the first 6 months of an infant’s life were maternal employment, maternal education, maternal age, and mode of delivery. The present research therefore recommends that Middle Eastern health care providers understand these determinants of breastfeeding so that they can provide detailed practical guidance to help mothers to overcome barriers where possible and, in doing so, assist in improving maternal and infant health outcomes in the region. Future research should examine the possible causations between key influencing factors and breastfeeding patterns and practices in the Middle East region by deploying more appropriate research designs, such as cohort studies, which are able to analyze follow-up data, and can therefore produce more accurate and insightful results.

Footnotes

Funding:The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declaration of conflicting interests:The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: RAA performed the literature search, and wrote and revised the manuscript.

References

- 1. Roth DE, Caulfield LE, Ezzati M, Black RE. Acute lower respiratory infections in childhood: opportunities for reducing the global burden through nutritional interventions. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:356–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kramer MS, Kakuma R. The optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;8:CD003517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization Collaborative Study Team on the Role of Breastfeeding on the Prevention of Infant Mortality. Effect of breastfeeding on infant and child mortality due to infectious diseases in less developed countries: a pooled analysis. Lancet. 2000;355:451–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arifeen S, Black RE, Antelman G, Baqui A, Caulfield L, Becker S. Exclusive breastfeeding reduces acute respiratory infection and diarrhea deaths among infants in Dhaka slums. Pediatrics. 2001;108:E67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Burr ML, Limb ES, Maguire MJ, et al. Infant feeding, wheezing, and allergy: a prospective study. Arch Dis Child. 1993;68:724–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ford RP, Taylor BJ, Mitchell EA, et al. Breastfeeding and the risk of sudden infant death syndrome. Int J Epidemiol. 1993;22:885–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ip S, Chung M, Raman G, et al. Breastfeeding and maternal and infant health outcomes in developed countries. Evid Rep Technol Asses. 2007;153:1–186. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kwan ML, Buffler PA, Abrams B, Kiley VA. Breastfeeding and the risk of childhood leukemia: a meta-analysis. Public Health Rep. 2004;119:521–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sadauskaite-Kuehne V, Ludvigsson J, Padaiga Z, Jasinskiene E, Samuelsson U. Longer breastfeeding is an independent protective factor against development of type 1 diabetes mellitus in childhood. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2004;20:150–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Butte NF, Lopez-Alarcon MG, Garza C. Nutrient Adequacy of Exclusive Breastfeeding for the Term Infant During the First Six Months of Life. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 11. World Health Organization (WHO). United Nations Children’s Fund: Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 12. American Academy of Pediatrics, Section on Breastfeeding. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e827–e841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Agostini C, Decsi T, Fewtrell M, et al. Complementary feeding: a commentary by the ESPGHAN Committee on Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;46:99–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jones JR, Kogan MD, Singh GK, Dee DL, Grummer-Strawn LM. Factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding in the United States. Pediatrics. 2011;128:1117–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dop MC, Benbouzid D, Trèche S, et al., eds. Complementary Feeding of Young Infants in Africa and the Middle East. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Boccolini CS, Carvalho ML, de Oliveira MI. Factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding in the first six months of life in Brazil: a systematic review. Rev Saude Publica. 2015;49:91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Amin T, Hablas H, Al Qader AA. Determinants of initiation and exclusivity of breastfeeding in Al Hassa, Saudi Arabia. Breastfeed Med. 2011;6:59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yngve A, Sjostrom M. Breastfeeding determinants and a suggested framework for action in Europe. Public Health Nutr. 2001;4:729–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dashti M, Scott JA, Edwards CA, Al-Sughayer M. Predictors of breastfeeding duration among women in Kuwait: results of a prospective cohort study. Nutrients. 2014;6:711–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gartner LM, Morton J, Lawrence RA, et al. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2005;115:496–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. World Health Organization, UNICEF. Indicators for Assessing Infant and Young Child Feeding Practices Part 3: Country Profiles. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23. World Health Organization (WHO). Infant and Young Child Feeding: Model Chapter for Textbooks for Medical Students and Allied Health Professionals. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Al-Kohji S, Said HA, Selim NA. Breastfeeding practice and determinants among Arab mothers in Qatar. Saudi Med J. 2012;33:436–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Batal M, Boulghourjian C, Abdallah A, Afifi R. Breast-feeding and feeding practices of infants in a developing country: a national survey in Lebanon. Public Health Nutr. 2006;9:313–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dorgham L, Hafez S, Kamhawy H, Hassan W. Assessment of initiation of breastfeeding, prevalence of exclusive breast feeding and their predictors in Taif, KSA. Life Sci J. 2014;11:1. [Google Scholar]

- 27. El-Gilany AH, Sarraf B, Al-Wehady A. Factors associated with timely initiation of breastfeeding in AL-Hassa Province, Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Health J. 2012;18:250–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Haghighi M, Taheri E. Factors associated with breastfeeding in the first hour after birth, in baby friendly hospitals, Shiraz-Iran. Int J Pediatr. 2015;3:889–896. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Radwan H. Patterns and determinants of breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices of Emirati Mothers in the United Arab Emirates. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yılmaz E, Doğa Öcal F, Vural Yılmaz Z, Ceyhan M, Kara OF, Küçüközkan T. Early initiation and exclusive breastfeeding: factors influencing the attitudes of mothers who gave birth in a baby-friendly hospital. Turk J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;14:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yılmaz E, Yılmaz Z, Isık H, et al. Factors associated with breastfeeding initiation and exclusive breastfeeding rates in Turkish adolescent mothers. Breastfeed Med. 2016;11:315–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Al-Akour NA, Okour A, Aldebes RT. Factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding practices among mothers in Syria: a cross-sectional study. Br J Med Med Res. 2014;4:2713–2724. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Al Ghwass A, Mohamed M, Dalia A. Prevalence and predictors of 6-month exclusive breastfeeding in a rural area in Egypt. Breastfeed Med. 2011;6:191–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Alyousefi NA, Alharbi AA, Almugheerah BA, et al. Factors influencing Saudi mothers success in exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of infant life: a cross-sectional observational study. Int J Med Res Health Sci. 2017;6:68–78. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Alzaheb RA. Factors influencing exclusive breastfeeding in Tabuk, Saudi Arabia. Clin Med Insights Pediatr. 2017;11. doi: 10.1177/1179556517698136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. El-Gilany AH, El-Wehady A, El-Hawary A. Maternal employment and maternity care in Al-Hassa, Saudi Arabia. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2008;13:304–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. El Shafei AM, Labib JR. Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding and introduction of complementary foods in rural Egyptian communities. Glob J Health Sci. 2014;6:236–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mahfouz MS, Kheir HM, Alnami AA, et al. Breastfeeding indicators in Jazan Region, Saudi Arabia. Br J Med Med Res. 2014;4:2229–2237. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Noughabi ZS, Tehrani SG, Foroushani AR, Nayeri F, Baheiraei A. Prevalence and factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months of life in Tehran: a population-based study. East Mediterr Health J. 2014;20:24–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vafaee A, Khabazkhoob M, Moradi A, Najafpoor AA. Prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding during the first six months of life and its determinant factors on the referring children to the health centers in Mashhad, Northeast of Iran-2007. J Appl Sci. 2010;10:343–348. [Google Scholar]

- 41. WHO/UNICEF. Baby-friendly hospital initiative. Revised, updated and expanded for integrated care. http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/bfhi/en/index.html. [PubMed]

- 42. Patil SS, Hasamnis AA, Pathare RS, Parmar A. Prevalence of exclusive breast feeding and its correlates in an urban slum in Western India. Int J Sci Med Educ. 2009;3:14–18. [Google Scholar]

- 43. World Health Organization. Infant and young child feeding: a tool for assessing national practices, policies and programmes. http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/infantfeeding/9241562544/en/. Published 2003.

- 44. Alebel A, Dejenu G, Mullu G, Abebe N, Gualu T, Eshetie S. Timely initiation of breastfeeding and its association with birth place in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Breastfeed J. 2017;12:44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. UNICEF. Improving Child Nutrition: The Achievable Imperative for Global Progress. New York, NY: UNICEF; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 46. World Health Organization. Appropriate technology for birth. Lancet. 1985;2:436–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Asfaw MM, Argaw MD, Kefene ZK. Factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding practices in Debre Berhan District, Central Ethiopia: a cross sectional community based study. Int Breastfeed J. 2015;10:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Abada TS, Trovato F, Lalu N. Determinants of breast-feeding in the Philippines: a survival analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52:71–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lakew Y, Tabar L, Haile D. Socio-medical determinants of timely breastfeeding initiation in Ethiopia: evidence from the 2011 nation wide demographic and health survey. Int Breastfeed J. 2015;10:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]