Abstract

Purpose: The aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of regular exercise incorporating mechanical devices on fatigue, gait pattern, mood, and quality of life in persons with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS). Method: A total of 55 individuals with RRMS with an Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score of 0–4.5 and a Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) score of 4.0 or more were randomly assigned to one of two exercise groups or a control group (n=18). Exercise programmes used aerobic, body weight, coordination, and balance exercises with either whole-body vibration (WBV; n=19; drop-outs, n=3) or the Balance Trainer system (n=18; drop-outs, n=4). Outcome measures included the FSS, Modified Fatigue Impact Scale (MFIS), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II), and Multiple Sclerosis International Quality of Life (MusiQoL). Spatiotemporal gait parameters were assessed using the GAITRite electronic walkway. Pre- and post-intervention assessments were performed by a blinded assessor. Intra- and inter-group analysis was performed, using the paired-samples t-test, by calculating the effect size with Cohen's d analysis and one-way analysis of variance, respectively. Results: Significant improvements in fatigue and mood were identified for both intervention groups (p<0.05). Gait parameters also improved significantly in the WBV group: velocity and step length increased (12.8% and 6.5%, respectively; p<0.005), and step time, stance time, double support time, and step length asymmetry decreased (–5.3%, –1.4%, –5.9%, and –43.7%, respectively; p<0.005). Conclusions: The results of this study support the hypothesis that combined training programmes help to reduce fatigue and improve mood in persons with mild to moderate RRMS. WBV combined with a standard exercise programme significantly improves spatiotemporal gait parameters.

Key Words: exercise therapy, fatigue, gait, multiple sclerosis, whole body vibration

Abstract

Objectif : la présente étude visait à évaluer les effets de l'exercice régulier incluant des appareils mécaniques sur la fatigue, les types de démarche, l'humeur et la qualité de vie de personnes ayant une sclérose en plaques rémittente (SPR). Méthodologie : au total, 55 personnes ayant une SPR, un score de 0 à 4,5 sur l'échelle étendue des incapacités (EDSS) et un score de 4,0 ou plus sur l'échelle de gravité de la fatigue (FSS) ont été divisées au hasard entre deux groupes d'exercices et un groupe témoin (CT, n=18). Les programmes d'exercices faisaient appel à l'aérobie, au poids du corps, à la coordination et aux exercices d'équilibre à l'aide de la vibration globale du corps (groupe WBV, n=19; abandons, n=3) ou du système d'entraînement à l'équilibre (groupe BT, n=18; abandons, n=4). Les mesures de résultats incluaient la FSS, l'échelle modifiée des répercussions sur la fatigue (MFIS), l'inventaire de dépression de Beck (BDI-II) et la qualité de vie de la fédération internationale de sclérose en plaques (MusiQoL). Les chercheurs ont évalué les paramètres de démarche spatiotemporelle au moyen de la piste électronique GAITRite. Un évaluateur a procédé à des évaluations à l'aveugle avant et après les interventions. Les chercheurs ont effectué des analyses intragroupes et intergroupes à l'aide du test de Student pour échantillons appariés, en calculant la taille de l'effet par l'analyse d de Cohen et l'analyse de variance unidirectionnelle, respectivement. Résultats : les chercheurs ont constaté une diminution significative de la fatigue et une amélioration significative de l'humeur dans les deux groupes d'intervention (p<0,05). Les paramètres de démarche se sont également améliorés de manière considérable dans le groupe de WBV : la vélocité et la longueur des pas ont augmenté (12,8 % et 6,5 %, respectivement; p<0,005), tandis que la durée des pas, la durée d'appui, la durée du double appui et l'asymétrie de la longueur des pas ont diminué (−5,3 %, −1,4 %, −5,9 % et −43,7 %, respectivement; p<0,005). Conclusion : les résultats de la présente étude appuient l'hypothèse selon laquelle des programmes d'entraînement combinés contribuent à réduire la fatigue et à améliorer l'humeur des personnes présentant une SPR. La WBV combinée à un programme d'exercices standard améliore considérablement les paramètres de la démarche spatiotemporelle.

Mots clés : démarche, fatigue, rééducation par l'exercice, sclérose en plaques, vibration globale du corps

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a neurodegenerative disease that affects an estimated 2.5 million adults around the world.1 MS has a wide range of symptoms, including muscle weakness, spasticity, impaired balance, paralysis, visual and sensory disturbances, cognitive dysfunction, and bladder and bowel symptoms.1 Fatigue occurs in persons with MS as “a subjective lack of physical and/or mental energy that is perceived by the individual or caregiver to interfere with usual and desired activities,”2(p.2) and patients have reported it to be one of the most common and disabling symptoms, with a prevalence ranging from 65% to 97%.3 It is the main cause of early work disability, inability to perform routine daily tasks, limitations in social relations, worsening of depressive symptoms, and reduction in health-related quality of life.4

Although there is sufficient evidence supporting the beneficial effects of exercise training in individuals with mild to moderate disability from MS, individuals with MS are generally less physically active than the healthy population.5 A recent systematic review proposed several modalities of exercise for persons with MS, including endurance, resistance, and combined training. Research has reported improvements in physical capacity (maximal oxygen consumption and muscular strength), mobility (6-min walk test and timed 25-ft walk test), fatigue, and quality of life (self-report questionnaires) with an exercise frequency of two to three times per week.6 The outcome depends on exercise modality, setting, and frequency. Furthermore, other studies have suggested that physical activity could even slow the progression of MS.7

Gait disturbances are another of the leading causes of consultations, based on patients' perception of disability and impact on quality of life.8 Approximately 85% of persons with MS show gait disturbance.9 This fact reveals the importance of periodically assessing gait to evaluate the progression of the disease and monitor the effects of rehabilitation therapies on gait parameters and symptoms.8 Previous studies have accurately described the spatiotemporal gait parameters of each stage of MS and identified decreased gait speed, cadence, and step length, as well as increased step time, in comparison with healthy subjects.9,10 Moreover, some spatiotemporal gait parameters significantly correlate with fatigue, including velocity (r=–0.339), step length (r=–0.274), step time (r=0.328), and double support time (r=0.373).11 These relationships reflect a complex interaction between fatigue and gait quality in which an increase in fatigue is accompanied by a decrease in gait quality or vice versa. Many symptoms lead to a higher energy cost of walking, such as muscular weakness, spasticity, or ataxia, and they increase fatigue and worsen gait parameters. Therefore, it is necessary to determine the effectiveness of new exercise programme models that address the complex interaction between fatigue and gait quality.

In recent years, different types of training, designed to improve fatigue, have been proposed for persons with MS. Whole-body vibration (WBV) is recommended as an exercise modality to increase muscle strength as a means of improving gait, balance, and functional mobility.12 WBV consists of an oscillating platform that transfers vibrations to the body, generating direct effects on the musculoskeletal system. Studies using WBV for 3 weeks in persons with MS showed improvements in the strength of the quadriceps, hamstrings, tibialis anterior, and gluteus medius.12,13 Other studies showed improvements in determinants of gait quality, such as strength, balance, and physical activity.14 Other researchers have described positive effects on motor control, proprioception, and neuromuscular coordination in untrained healthy persons,12 elderly persons,15 persons with stroke,16 and persons with Parkinson's disease.17

Another device that complements physiotherapy interventions is the Balance Trainer (BT), a recently developed mechanical device for training balance. It provides a fall-safe balancing environment for training the pelvic, lower limb, and trunk musculature during standing.18 Studies have shown improvements in postural control during gait when the BT was used with patients with subacute and chronic stroke;18,19 as such, it may be a feasible tool for rehabilitation of persons with MS.

The rationale for our study is based on previous research that has shown that a combined training programme (aerobic, resistance, and balance exercises) influences, directly and indirectly, the perception of fatigue and gait parameters. The exercise programme format—a circuit delivered in a small group—would address the specific needs of the group and encourage members to learn the exercises and improve their adherence to treatment.20 Moreover, incorporating mechanical devices into the exercise regimen would enable individuals to practice in a fall-safe environment. In addition, after a physiotherapist had prepared and instructed a patient, demands on the therapist would decrease, thereby reducing the costs of an individual session.

We hypothesized that a 12-week combined training programme incorporating mechanical devices (WBV and BT) would improve fatigue, gait pattern, mood, and quality of life in persons with relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS).

This article reflects the work resulting from a pilot study; it was presented at the 2013 annual meeting of the Spanish Society of Neurology in Barcelona, Spain.

Methods

Study design

Our study was a pretest–posttest, randomized, controlled, blinded trial designed to evaluate the effects of a 12-week, twice-weekly combined training programme on fatigue, gait pattern, mood, and quality of life in persons with RRMS.

Participants

The study group consisted of persons with clinically diagnosed RRMS with an Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS)21,22 score between 0 and 4.5. This scale is a well-established clinical measure to determine the level of neurological impairment in MS; it includes 10 levels of disability ranging from 0 (“no disability”) to 10 (“death due to MS”). EDSS scores between 0.0 and 4.5 represent mild to moderate disability, and scores higher than 4.5 represent severe disability. Also were included those with a Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) score of 4 or more and an initial clinical history showing fatigue as one of the most disabling symptoms affecting their ability to perform their daily living activities.23 Individuals who met any one of the following criteria were excluded from the final analysis: (1) those reporting an MS relapse during the 3 months immediately before the study began (excluded from enrolment) or those who had a relapse during the study (dropped from participation); (2) cognitive impairment that would interfere with study participation; (3) comorbidity that prevented autonomous walking, standing, or aerobic exercise (e.g., unable to ride a stationary bicycle); (4) pregnancy; or (5) participation in any exercise programme at our unit in the preceding 3 months.

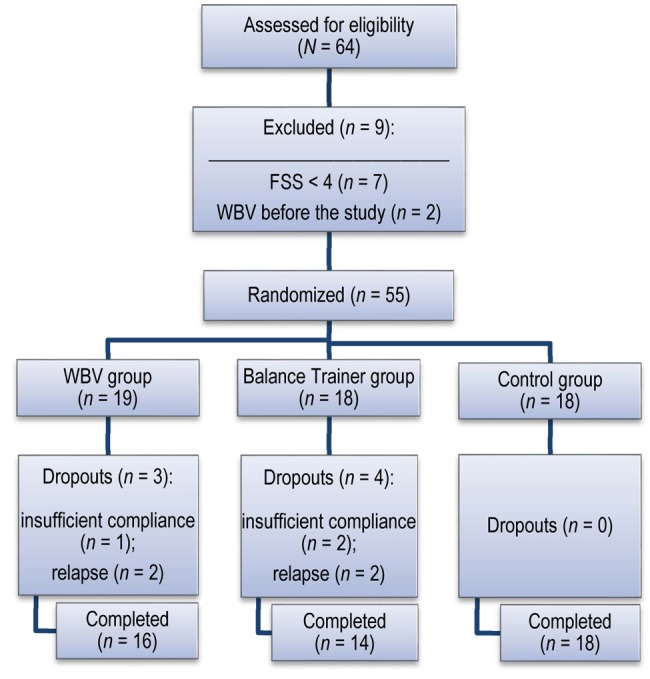

A total of 64 persons with RRMS were recruited by one neurologist from MS units in University Hospital Virgen Macarena (Seville, Spain). Seven individuals were excluded because of a low level of fatigue (FSS<4), and 2 were excluded because, before the study began, they had participated in exercise programmes that included WBV. (See the study flow diagram in Figure 1.) Participants meeting the inclusion criteria were randomly assigned to one of three groups using a random numbers table. (Table 1 provides demographic information about the study population.) Signed informed consent, approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Virgen Macarena (CEIC 1896), was obtained for the individuals included in the study (Trial ID no. ACTRN12615000449538).

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram. FSS=Fatigue Severity Scale; WBV=whole-body vibration.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Participants (n=48)

| Group; mean (SD)* |

|||

| Characteristic | WBV (n=16) | BT (n=14) | CT (n=18) |

| Sex, male:female | 6:10 | 5:9 | 4:14 |

| Age, y | 43.1 (10.2) | 40.3 (8.9) | 43.0 (9.3) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.2 (3.5) | 23.5 (2.9) | 27.2 (6.9) |

| EDSS score | 3.0 (1.0) | 3.2 (1.1) | 3.2 (1.1) |

| Years since diagnosis | 10.5 (8.8) | 7.4 (5.0) | 8.0 (5.4) |

| Assistive device (cane or crutch), no. | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Active worker, yes:no | 8:8 | 7:7 | 9:9 |

| Exercise history† | 0.8 (0.9) | 0.8 (0.9) | 0.8 (1.0) |

Unless otherwise indicated.

No. of days of exercise per week during the previous 6 mo.

WBV=whole-body vibration; BT=Balance Trainer; CT=control; EDSS=Expanded Disability Status Scale.

Outcome measures

Fatigue

We assessed fatigue using self-reported measures: the Spanish versions of the FSS and the Modified Fatigue Impact Scale (MFIS). The FSS is a one-dimensional scale that evaluates the effect of fatigue on function; it is based on nine items scored on a scale ranging from 1 to 7, representing the least to the greatest amount of fatigue. It has been validated in an MS population with acceptable test–retest reproducibility. An FSS score of 4 was used as the cutoff value for defining fatigue.23,24

The MFIS is a self-administered, multidimensional questionnaire used to evaluate the fatigue that a person has experienced during the previous 4 weeks. A total of 21 items are rated on a scale ranging from 0 (“never”) to 4 (“almost always”), differentiating the impact on physical, cognitive, and psychosocial functioning; each sub-scale score has its own range: physical (MFIS–physical), 0–36; cognitive (MFIS–cognitive), 0–40; and psychosocial (MFIS–psychosocial), 0–8. The total score ranges from 0 to 84, with 38 used as the cutoff value for fatigue.24 The Spanish version showed no cultural or linguistic differences with respect to the original.25

Quality of life

We used the Spanish version of the Multiple Sclerosis International Quality of Life (MusiQoL) to measure health-related quality of life. The MusiQoL is a self-administered, multidimensional, 31-item questionnaire validated for measuring quality of life in persons with MS. It describes nine dimensions covering physical, mental, and social aspects of health; all dimension scores were linearly transformed, then converted to a scale ranging from 0 to 100, where 0=“worse quality of life” and 100=“higher quality of life.” A global index score was computed as the mean of the dimension scores.26

Mood

The Beck Depression Inventory–II (BDI–II) is a 21-item self-report measure that assesses affective, cognitive, and somatic symptoms of depression. For each item, participants chose one of four alternatives that best described their condition during the preceding 2 weeks. A total score was computed, ranging from 0 to 63. BDI–II scores of 0–13 indicate minimal depression; 14–19, mild depression; 20–28, moderate depression; and 29 or higher, severe depression.27 This questionnaire has shown good internal consistency, reliability, and validity in the Spanish population.28

Gait analysis

We examined gait using the GAITRite electronic walkway, a portable gait analysis system. The walkway is connected to a computer via USB (or flash drive) to collect and process data. Sensors along the walkway are activated by the mechanical pressure of the subject walking on it.29 Using the sensor grid geometry and scan times, the software calculates the spatiotemporal gait parameters and provides rapid, clinically relevant measurements of gait.9,30 The integrated Functional Ambulation Profile (FAP), quantified on a numerical scale ranging from 30 (“unable to walk”) to 100 (“unimpaired gait”), has been validated as a gait impairment marker in people with MS with good test–retest reliability.31 The FAP score is calculated using the measures of function for each leg (base of support, asymmetries between each step) and the use of assistance (mechanical assistive devices or verbal support).

Participants walked along the walkway four times at their own preferred pace, with intervening rest intervals, to control for variations in fatigue. The passes were averaged to create an individual score, to control for variations in gait parameters. No gait aids or orthoses were used during the gait testing. The gait parameters included in the analysis were FAP, velocity (cm/sec), step length (cm), base of support (cm), step time (sec), stance time (% gait cycle), double support time (% gait cycle), and step length asymmetry (cm).

Testing procedure

We performed the initial assessment over two visits. At the first visit, the neurologist interviewed the patients to determine an EDSS score. Patients who needed treatment were referred to the Neurophysiotherapy Unit, where an experienced neurologic physical therapist, the blinded assessor, assessed them in terms of the study's inclusion and exclusion criteria. Participants admitted into the study completed self-report questionnaires (FSS, MFIS, BDI–II, and MusiQoL) and gait analysis (using the GAITRite system). A second neurologic physical therapist allocated participants to one of the three study groups. The final assessment was made by the blinded assessor 12 weeks after the intervention, following the same protocol. The study was carried out between May 3, 2013, and April 18, 2014.

Exercise programme

We designed the interventions on the basis of the intensity, frequency, and duration established in recent reviews5,6 and on the hypothesis that WBV or BT, in addition to a standard exercise programme, could improve fatigue and gait pattern. Exercise programmes were scheduled twice a week over a 12-week period (24 sessions in total) in a circuit training format, administered as a group exercise programme (four to eight individuals per group) adapted for individuals and supervised and guided by a neurologic physical therapist. The duration of the interventions increased by 5 minutes per week: from 60 minutes in the first week to 100 minutes in the ninth week. The intensity was based on the Borg scale of rating of perceived exertion, which gradually increased from a value of 11–12 (“light”) to 13–15 (“somewhat hard”). During exercise, participants were asked to determine their rating of perceived exertion, with the goal of having them adapt to the level of effort required at each stage. All participants understood the progression of the exercise programme. The programme was occasionally adapted to accommodate conditions that exacerbated fatigue (i.e., climatic changes), reducing the intensity of exercise and increasing the rest periods between exercises. A summary of interventions is shown in the Appendix.

We divided the participants into three groups: a WBV group, a BT group, and a control (CT) group. The CT group consisted of individuals on a wait-list to receive treatment, who were offered a standard exercise programme that included WBV after 12 weeks. For the first two groups, the nature of the programme was the same: It started with a 5-minute warm-up (general joint mobilizations), then 15–30 minutes of aerobic exercise (e.g., stationary bike, treadmill walking, elliptical, or brisk walking along a 150 m long circular corridor). After this, 15–30 minutes of circuit exercises were performed, including body weight, coordination, and balance exercises (e.g., squats, walking in a straight line, and unilateral weight bearing, dual-task, and Pilates ball exercises). Finally, participants performed a combination of stretching exercises for the major muscle groups that lasted 15 minutes, followed by 5 minutes of cool-down, incorporating relaxation and breathing. There were breaks between exercises, and the exercise programme was progressive and tailored toward individual abilities.

The exercise groups used different devices to complete the circuit exercises. The WBV group performed exercises (amplitude=3 mm, average frequency=4 Hz±1 Hz/sec) using a Zeptor Med System (Scisen GmbH, Frankfurt, Germany). Vibrations transmitted to the body stimulate the participants' muscle spindles, generating subconscious muscle contractions. The platform generates a non-harmonious oscillating movement along the horizontal and vertical planes, avoiding habituation of the receptors.32 During the WBV exercise session, participants were instructed to maintain a squat position with slight flexion at the hips, knees, and ankle joints for 90 seconds. Five repetitions were performed, with 1-minute breaks. The system was set to deliver vibrations at an amplitude of 3 millimetres and average frequency of 4 Hertz±1 Hertz per second.

Figure 2.

Participant training on the whole-body vibrator (whole-body vibration group).

The BT group trained in dynamic balance with the BT system, a commercially available mechanical device that provides a fall-safe balancing environment (Medica Medizintechnik GmbH, Hochdorf, Germany).18 The BT software (Balance-Soft version 01.04.02) includes different types of exercises and games that force a person's centre of gravity to be shifted in different directions, thereby activating their leg, pelvis, and trunk muscles.18,19 Interacting with the computer, participants performed exercises over a 15-minute period to train dynamic balance in the sagittal and frontal planes (unipedal and bipedal stance).

Figure 3.

Participant training on the Balance Trainer (Balance Trainer group).

Statistical analysis

We performed the statistical analysis using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 22.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY). We tested all parameters for normal distribution using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Differences in demographic characteristics among the three groups were examined using the χ2 test for qualitative variables and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Comparisons among measures, pre- and post-intervention (intra-group analysis), were assessed using the paired-samples t test. We used one-way ANOVA to test differences between groups (inter-group analysis), and the Bonferroni correction for pair-wise comparisons. We calculated the size impact of the intervention effect using Cohen's d analysis ([post-intervention—baseline mean scores] / SD of the change in mean scores over time), with a small effect size defined as 0.2–0.5; moderate effect size, 0.5–0.8; and large effect size, 0.8 or greater.33 Clinical effectiveness was also calculated as the percentage of change for all outcome measures post-intervention for every group ([baseline value—post-intervention value] / baseline value×100). Alpha was set at p<0.05.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 55 participants were allocated to one of two intervention groups (WBV or BT) or to the CT (wait-list) group. Four were subsequently excluded because of relapse and 3 for insufficient compliance, resulting in 48 persons with RRMS assessed pre- and post-intervention: 16 in the WBV group, 14 in the BT group, and 18 in the CT group. Their mean age was 44 years (range 22–62), the mean EDSS score was less than 3.5 (range 1.5–4.5), and the proportion of women was higher in each group. No statistical differences were seen among the three groups in terms of demographics (see Table 1) or baseline assessments (see Tables 2 and 3). The number of sessions expected was 24. Participation was 80.0% in the WBV group and 79.5% in the BT group; this is similar to other studies.34,35 The 3 participants who had insufficient compliance failed to attend more than 30% of the sessions (>8 of the total 24), and they were not assessed at the end of the intervention. No accidents or adverse effects related to exercising were reported.

Table 2.

Baseline and Post-Intervention Values on Self-Reported Measures (n=48)

| Mean (SD) |

Inter-group |

|||||

| Value and group | Baseline | Post-intervention | Clinical effect (%)* | Effect size (Cohen's d) | F2,45 | p-value† |

| FSS | 6.7 | 0.003 | ||||

| WBV | 5.9 (0.8) | 4.5 (1.8) | −24.4‡ | 0.89§ | ||

| BT | 5.4 (1.0) | 5.1 (1.4) | −5.3 | 0.20 | ||

| CT | 5.7 (0.9) | 5.9 (1.2) | 2.6 | 0.20 | ||

| MFIS–overall | 4.2 | 0.021¶ | ||||

| WBV | 49.7 (13.3) | 41.6 (14.3) | −16.2‡ | 0.70 | ||

| BT | 50.6 (17.4) | 42.7 (20.8) | −15.7‡ | 0.68 | ||

| CT | 49.0 (11.1) | 51.3 (18.4) | 4.8 | 0.19 | ||

| MFIS–physical | 7.7 | 0.001¶,** | ||||

| WBV | 24.9 (5.7) | 18.1 (6.3) | −27.4‡ | 0.98§ | ||

| BT | 26.9 (6.4) | 19.6 (8.3) | −26.9‡ | 1.11§ | ||

| CT | 25.8 (5.6) | 26.3 (6.8) | 2.2 | 0.09 | ||

| MFIS–cognitive | 0.5 | 0.615 | ||||

| WBV | 20.3 (8.6) | 19.6 (8.2) | −3.4 | 0.11 | ||

| BT | 19.3 (11.7) | 19.6 (12.2) | 1.5 | 0.06 | ||

| CT | 18.6 (8.6) | 20.1 (11.7) | 7.8 | 0.20 | ||

| MFIS–psychosocial | 1.3 | 0.289 | ||||

| WBV | 4.4 (2.2) | 3.9 (1.5) | −11.3 | 0.43 | ||

| BT | 4.5 (2.4) | 3.8 (2.0) | −15.9 | 0.30 | ||

| CT | 4.6 (1.5) | 4.9 (2.4) | 7.2 | 0.15 | ||

| BDI–II | 5.2 | 0.009** | ||||

| WBV | 17.7 (7.7) | 14.6 (6.7) | −20.3‡ | 0.55 | ||

| BT | 18.9 (11.7) | 12.8 (11.0) | −32.2‡ | 0.69 | ||

| CT | 17.7 (10.6) | 18.8 (10.2) | 6.3 | 0.30 | ||

| MusiQoL | 2.0 | 0.145 | ||||

| WBV | 64.2 (11.6) | 64.8 (12.8) | 1 | 0.12 | ||

| BT | 64.6 (12.2) | 66.7 (13.7) | 3.3 | 0.34 | ||

| CT | 61.5 (10.6) | 58.5 (15.1) | −5 | 0.31 | ||

Calculated as (baseline value—post-intervention value) / baseline value×100.

Inter-group p-value is the result of one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni correction for pair-wise comparisons:

Intra-group p-value<0.05 (paired-samples t-test).

d ≥ 0.8.

Difference between WBV group and CT group (p<0.05).

Difference between BT group and CT group (p<0.05).

FSS=Fatigue Severity Scale; WBV=whole-body vibration; BT=Balance Trainer; CT=control; MFIS=Modified Fatigue Impact Scale; BDI–II=Beck Depression Inventory–II; MusiQoL=Multiple Sclerosis International Quality of Life.

Table 3.

Baseline and Post-Intervention Values of Spatiotemporal Gait Parameters (n=48)

| Mean (SD) |

Inter-group |

|||||

| Value and group | Baseline | Post-intervention | Clinical effect (%)* | Effect size (Cohen's d) | F2,45 | p-value† |

| FAP | 5.9 | 0.005‡ | ||||

| WBV | 94.7 (6.7) | 97.3 (4.5) | 2.8§ | 0.79¶ | ||

| BT | 93.9 (7.0) | 95.1 (8.3) | 1.3 | 0.33 | ||

| CT | 93.5 (5.8) | 91.6 (9.1) | −2.1 | 0.42 | ||

| Velocity, cm/sec | 6.4 | 0.004‡ | ||||

| WBV | 101.7 (14.6) | 114.7 (14.2) | 12.8§ | 1.22¶ | ||

| BT | 99.4 (15.6) | 104.6 (19.7) | 5.3 | 0.50 | ||

| CT | 97.4 (17.2) | 96.0 (21.3) | −1.5 | 0.11 | ||

| Step length, cm | 5.2 | 0.009‡ | ||||

| WBV | 60.1 (7.1) | 64.0 (84.7) | 6.5§ | 1.09¶ | ||

| BT | 59.0 (8.0) | 60.4 (8.6) | 2.4 | 0.35 | ||

| CT | 56.7 (7.7) | 56.2 (9.2) | −0.9 | 0.12 | ||

| Base of support, cm | 0.1 | 0.961 | ||||

| WBV | 10.4 (4.4) | 10.8 (4.6) | 4.2 | 0.38 | ||

| BT | 10.1 (2.7) | 10.7 (3.0) | 5.8 | 0.26 | ||

| CT | 10.3 (2.8) | 10.7 (2.9) | 4 | 0.22 | ||

| Step time, sec | 3.7 | 0.032‡ | ||||

| WBV | 0.60 (0.04) | 0.56 (0.05) | −5.3§ | 0.82¶ | ||

| BT | 0.60 (0.07) | 0.59 (0.09) | −1.8 | 0.27 | ||

| CT | 0.59 (0.06) | 0.60 (0.06) | 1.1 | 0.15 | ||

| Stance time, % GC | 2.3 | 0.109 | ||||

| WBV | 64.8 (2.3) | 63.9 (2.2) | −1.4§ | 0.64 | ||

| BT | 64.3 (1.4) | 64.3 (1.6) | 0 | 0.01 | ||

| CT | 65.3 (2.1) | 65.2 (2.6) | −0.1 | 0.05 | ||

| Double support time, % GC | 1.0 | 0.365 | ||||

| WBV | 29.5 (4.8) | 27.8 (4.1) | −5.9§ | 0.65 | ||

| BT | 28.7 (2.9) | 28.7 (3.5) | 0 | 0.00 | ||

| CT | 30.6 (4.1) | 30.5 (5.1) | −0.3 | 0.04 | ||

| Step length asymmetry, cm | 3.8 | 0.029Dagger; | ||||

| WBV | 3.4 (2.4) | 1.9 (1.5) | −43.7§ | 0.70 | ||

| BT | 3.2 (3.4) | 2.4 (1.9) | −26.2 | 0.36 | ||

| CT | 2.7 (1.9) | 3.1 (2.1) | 12.8 | 0.25 | ||

Calculated as (baseline value—post-intervention value) / baseline value×100.

Inter-group p-value is the result of one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni correction for pair-wise comparisons:

Different between WBV group and CT group (p<0.05).

Intra-group p-value<0.05 (paired-samples t-test).

d≥0.8.

FAP=Functional Ambulation Profile; WBV=whole-body vibration; BT=Balance Trainer; CT=control; % GC=percentage of gait cycle.

Effect of training on self-reported measures

Both intervention groups showed significant improvements in self-reported fatigue and mood (see Table 2): The WBV and BT groups showed statistically significant decreases in scores on the MFIS–overall, MFIS–physical, and BDI–II. No group showed significant differences in scores on the MFIS–cognitive, MFIS–psychosocial, or MusiQoL. The CT group exhibited a slight tendency toward increased fatigue, worsening mood, and decreased quality of life. In the pair-wise comparison, the WBV group showed greater improvement in fatigue over the CT group on the FSS (p=0.003), MFIS–overall (p = 0.045), and MFIS–physical (p=0.005), and the BT group showed improvement on the MFIS–physical (p=0.005) and BDI–II (p=0.010) compared with the CT group. No statistically significant difference between the WBV and BT groups was found (p>0.05).

Effect of training on spatiotemporal gait parameters

The WBV group showed significant improvement on almost all spatiotemporal gait parameters, including increased FAP score (p=0.009), velocity (p<0.001), and step length (p=0.002) and decreased step time (p=0.004), stance time (p=0.022), double support time (p=0.020), and step length asymmetry (p=0.015). In the BT group, gait parameters followed the same trend as in the WBV group, but the results were not significant. The CT group showed a slight tendency toward worse spatiotemporal gait parameters: There was a decrease in the FAP score and velocity and an increase in step length asymmetry, but neither was statistically significant (p>0.05). With regard to the clinical effect, significant differences were found between the WBV and CT groups in FAP (p=0.005), velocity (p=0.003), step length (p=0.007), and step length asymmetry (p=0.028). No changes were observed in the base of support for any group. No statistically significant differences between the WBV group and the BT group were found in spatiotemporal gait parameters.

Discussion

This study evaluated the effects of a twice-weekly 12-week training programme that incorporated mechanical devices on fatigue, gait pattern, mood, and quality of life in persons with RRMS. Fatigue and gait abnormalities are symptoms that have a significant impact on the performance of activities of daily living for people with MS. In the scientific literature, many physiotherapy-based approaches are reported to address mobility and MS-related symptoms, including resistance, endurance, or combined training; functional electric stimulation; robotic-assisted training; and energy conservation management.6,36

We hypothesized that a combined training programme incorporating mechanical devices (WBV and BT) would improve fatigue and gait pattern. We also thought that this approach would enable patients with MS to take part in their recovery process with a more proactive attitude and involvement in their treatment while permitting a physiotherapist to assist several patients at once.

Other studies have included WBV in training programmes; they described improvements in the endurance component of walking ability (6-minute walk test) or the coordination component of mobility (timed up and go test and postural sway).12,14 Our study includes other outcome measures as well, such as perception of fatigue and gait pattern. Our results show that both intervention groups improved in terms of their perception of fatigue. In addition, the WBV group showed improved spatiotemporal gait parameters; these included faster and more symmetric gait, longer and faster steps, and reduced stance and double support phases.

Despite their initial willingness to participate in the study and our encouragement to continue the programme, three participants dropped out. The reasons are unclear, but we suspect that they had to do with the participants' personality, emotional status, and uncertainty about the positive effect of the treatment. Future interventions should provide education on the benefits of adhering to treatment.

Self-reported measures

Our data show that the WBV group improved 27.4% on the MFIS–physical and 24.4% on the FSS, with a large effect size (d>0.8). The BT group improved on these measures by 26.9% (d>0.8) and 5.3% (d=0.2), respectively. Although these two scales have shown good correlation (r=0.74),37 only the WBV group showed a similar percentage of change on both scales. These results suggest that the MFIS–physical may be more sensitive to change in perceived fatigue after rehabilitation interventions or that changes in fatigue in the BT group were more discreet. No changes were found in the psychological and social aspects of fatigue in the intervention groups. This might be because the intervention approach focused mainly on improving physical performance and functional capabilities. Recent studies have suggested that a multimodal approach should be used to address fatigue in persons with MS, combining psychological and physical aspects,38,39 or that therapy should be selected on the basis of what is most appropriate for each person, such as aerobic training, cognitive–behavioural therapy, or energy conservation management.40

Previous studies using self-report measures support our results. Learmonth and colleagues,34 in a group exercise intervention of combined exercise training, found a 9% reduction in fatigue as measured by the FSS—smaller than that found in our study. This difference in effect could be due to that study's average EDSS score of 6, compared with our study's average EDSS score of 3.5. However, the increases they observed in lower limb muscle strength, activity levels, and balance may explain part of the effects of our intervention.

Researchers have reported the correlation between fatigue, depression, and quality of life3,24,41 and the benefits of physical exercise on the improvement of these MS-related symptoms.5,6,40 In our study, we observed improvements in mood in both groups, but improvement was not seen in quality of life. Roppolo and colleagues41 obtained similar results, showing improvements in fatigue and mood, and they highlighted the role of fatigue as a mediator in the worsening of depression. In contrast to our study, they found improvements in quality of life, perhaps because the scale and sub-analysis used were different (MusiQoL–54).

Spatiotemporal gait parameters

Our study reports several new findings. Incorporating WBV into a circuit training programme resulted in modified spatiotemporal parameters. We interpret these changes as improvements in gait pattern, energy cost of walking, and walking safety, as research by Motl and colleagues has suggested.42 Two other studies have used GAITRite to analyze the effect of neuro-rehabilitation interventions on persons with MS. For example, Sacco and colleagues43 found improvements in some gait parameters such as speed, stance time, double support time, and stride length in 24 inpatients with MS. They also assessed fatigue and concluded that the changes in gait parameters correlated with improvements in fatigue. Another pilot study35 used a combined training programme and, despite differences in EDSS (range between 4.0 and 6.0), the percentage of change was similar to our findings for FAP (7%), velocity (10%), step length (7%), and single support time and stance time (3%).

We found a reduction in step length asymmetry in both intervention groups, but this change was significant only in the WBV group. Kalron and colleagues11,44 reported that persons with MS who had fatigue or a high risk of falling tended to have an asymmetric gait pattern (differences between legs in terms of step length, step time, single support time, or stance phase time). Therefore, the changes showed in our study could point to an improvement in gait quality, energy cost of walking, and reduced fall risk. To our knowledge, gait asymmetry parameters have not been used as an outcome measure in longitudinal studies. The meaningful characteristics and clinical relevance of these parameters are an important issue for future research.

Although previous studies using WBV in persons with MS did not measure gait parameters, they found improvements in mobility, postural control,32 and muscle strength in the lower limbs.13 Although it is generally accepted that WBV training benefits people with MS,12 the literature has reported contradictory findings concerning its efficacy. For example, Broekmans and colleagues45 did not find significant changes in leg muscle strength or functional capacity in persons with MS (assessed using the Berg Balance Scale, timed up-and-go, 2-minute walk test, or timed 25-ft walk test). A possible explanation for this might be the wide range of EDSS scores (1.5–6.5) and MS types included in that study; stratification of the analysis according to disease severity or type of MS would provide more reliable results.7 However, the frequency and amplitude of the WBV could explain some of the differences, as summarized in detail by Rittweger.46

Our study subjects showed improvements in spatiotemporal gait parameters and fatigue using a training exercise intervention that incorporated mechanical devices. We suggest incorporating WBV into training programmes at a low frequency, with the aim of improving gait pattern and perception of fatigue. We also recommend using the spatiotemporal gait parameters,47 in combination with functional capacity tests and validated scales, both in clinical practice and in research. Identifying these walking alterations will enable physiotherapy interventions to take a targeted therapeutic approach. Finally, the relationship between perception of fatigue and spatiotemporal gait parameters warrants further investigation.

Our study has several limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small, and our results may be limited in their generalizability to a general population. Second, the questionnaires, such as MusiQoL, are rarely used in rehabilitation studies; as a result, it is difficult to compare our results with those of other trials. Third, our restrictive inclusion criteria (relapsing-remitting sub-type, EDSS score ≤ 4.5, and FSS score < 4) make the results difficult to extrapolate. Fourth, to determine the specific effect of a mechanical device (WBV or BT), we would have had to conduct the standard exercise programme with another intervention group, without using a device. The effect of devices on gait parameters compared with a control group should be investigated. In this sense, our opinion is that WBV could benefit persons with MS, and BT may be appropriate for persons with severe disability (EDSS>4.5). The final limitation of our study is that the lack of a follow-up test prevented us from being able to evaluate how well the changes were maintained over time.

Conclusions

The results of this study support the hypothesis that combined training programmes help to reduce the perception of fatigue and improve mood in persons with mild to moderate RRMS. WBV combined with a standard exercise programme significantly improves spatiotemporal gait parameters; this includes increasing the FAP score, velocity, and step length and decreasing step time, stance time, double support time, and step length asymmetry.

Key Messages

What is already known on this topic

Fatigue and gait alterations are the most common and disabling symptoms of multiple sclerosis (MS). They represent major challenges for physiotherapists because of their high prevalence and impact on performance of activities of daily living.3,8 Previous studies have supported the beneficial effects of several modalities of exercise for persons with MS.6 Whole-body vibration (WBV) is recommended as an exercise modality and complement to exercise programmes.12 However, it is necessary to determine the effectiveness of a combined training programme incorporating mechanical devices (i.e., WBV) in fatigue and spatiotemporal gait parameters in persons with relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS).

What this study adds

This study reports the effects of a combined training programme incorporating mechanical devices (WBV or Balance Trainer) on fatigue, spatiotemporal gait parameters, mood, and quality of life in persons with RRMS. The circuit training programme has a positive effect on fatigue and mood. In addition, incorporating WBV results in a better gait pattern: faster and more symmetric gait, longer and faster steps, and reduced stance and double support times. Whether the changes in spatiotemporal gait parameters are correlated with improvements in functional capacity and the level of activity and social participation of person with MS should be further explored.

Appendix

Summary of Interventions and Duration in Minutes

| Overall duration, wk (min) |

|||||

| Exercise modality | 1–2 (60) | 3–4 (70) | 5–6 (80) | 7–8 (90) | 9–12 (100) |

| Warm-up (general joint mobilizations) | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Aerobic (stationary bike, treadmill walking, elliptical, or brisk walking) | 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 | 30 |

| Circuit exercises (body weight, coordination, and balance exercises—e.g., squats, walking in a straight line, and unilateral weight-bearing, dual-task, and Pilates ball exercises): WBV group, 5 reps×90 sec, 1 min rest; BT group, 15 min BT | 30 | 35 | 40 | 45 | 45 |

| Stretching and cool down (stretching major muscle groups, relaxation, breathing) | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 20 |

| 11–12 (“light”) | 13–14 (“somewhat hard”) | 13–15* (“somewhat hard”) | |||

Occasional peaks were reached, where 15=“hard.”

WBV=whole-body vibration; BT=balance trainer.

References

- 1. Kingwell E, Marriott JJ, Jetté N, et al. Incidence and prevalence of multiple sclerosis in Europe: a systematic review. BMC Neurol. 2013;13(1):128 https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-13-128. Medline:24070256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Multiple Sclerosis Council for Clinical Practice Guidelines. Fatigue and multiple sclerosis: evidence-based management strategies for fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Washington, DC: Paralyzed Veterans of America; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bakshi R. Fatigue associated with multiple sclerosis: diagnosis, impact and management. Mult Scler. 2003;9(3):219–27. https://doi.org/10.1191/1352458503ms904oa. Medline:12814166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fisk JD, Pontefract A, Ritvo PG, et al. The impact of fatigue on patients with multiple sclerosis. Can J Neurol Sci. 1994;21(1):9–14. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0317167100048691. Medline:8180914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Motl RW, Pilutti LA. The benefits of exercise training in multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurol. 2012;8(9):487–97. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2012.136. Medline:22825702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Latimer-Cheung AE, Pilutti LA, Hicks AL, et al. Effects of exercise training on fitness, mobility, fatigue, and health-related quality of life among adults with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review to inform guideline development. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94(9):1800–1828.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2013.04.020. Medline:23669008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dalgas U, Stenager E. Exercise and disease progression in multiple sclerosis: can exercise slow down the progression of multiple sclerosis? Ther Adv Neurol Disorder. 2012;5(2):81–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/1756285611430719. Medline:22435073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. LaRocca NG. Impact of walking impairment in multiple sclerosis: perspectives of patients and care partners. Patient. 2011;4(3):189–201. https://doi.org/10.2165/11591150-000000000-00000. Medline:21766914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Givon U, Zeilig G, Achiron A. Gait analysis in multiple sclerosis: characterization of temporal-spatial parameters using GAITRite functional ambulation system. Gait Posture. 2009;29(1):138–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2008.07.011. Medline:18951800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lizrova Preiningerova J, Novotna K, Rusz J, et al. Spatial and temporal characteristics of gait as outcome measures in multiple sclerosis (EDSS 0 to 6.5). J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2015;12(1):14 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-015-0001-0. Medline:25890382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kalron A. Association between perceived fatigue and gait parameters measured by an instrumented treadmill in people with multiple sclerosis: a cross-sectional study. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2015;12(1):34 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-015-0028-2. Medline:25885551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Santos-Filho SD, Cameron MH, Bernardo-Filho M. Benefits of whole-body vibration with an oscillating platform for people with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Mult Scler Int. 2012(2012):274728 https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/274728. Medline:22685660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Claerbout M, Gebara B, Ilsbroukx S, et al. Effects of 3 weeks' whole body vibration training on muscle strength and functional mobility in hospitalized persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2012;18(4):498–505. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458511423267. Medline:22084490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hilgers C, Mündermann A, Riehle H, et al. Effects of whole-body vibration training on physical function in patients with multiple sclerosis. NeuroRehabilitation. 2013;32(3):655–63. https://doi.org/10.3233/NRE-130888. Medline:23648620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Roelants M, Delecluse C, Verschueren SM. Whole-body-vibration training increases knee-extension strength and speed of movement in older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(6):901–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52256.x. Medline:15161453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yang X, Wang P, Liu C, et al. The effect of whole body vibration on balance, gait performance and mobility in people with stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rehabil. 2014;29(7):627–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215514552829. Medline:25311142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sharififar S, Coronado RA, Romero S, et al. The effects of whole body vibration on mobility and balance in Parkinson disease: a systematic review. Iran J Med Sci. 2014;39(4):318–26. Medline:25031483. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Goljar N, Burger H, Rudolf M, et al. Improving balance in subacute stroke patients: a randomized controlled study. Int J Rehabil Res. 2010;33(3):205–10. https://doi.org/10.1097/MRR.0b013e328333de61. Medline:20071998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Matjacić Z, Hesse S, Sinkjaer T. BalanceReTrainer: a new standing-balance training apparatus and methods applied to a chronic hemiparetic subject with a neglect syndrome. NeuroRehabilitation. 2003;18(3):251–9. Medline:14530590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Moore G, Durstine JL, Patricia P. Exercise management for persons with chronic diseases and disabilities. 3rd ed. Indianapolis (IN): American College of Sports Medicine; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol. 2011;69(2):292–302. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.22366. Medline:21387374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology. 1983;33(11):1444–52. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.33.11.1444. Medline:6685237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Krupp LB, LaRocca NG, Muir-Nash J, et al. The Fatigue Severity Scale. Application to patients with multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Neurol. 1989;46(10):1121–3. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneur.1989.00520460115022. Medline:2803071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Téllez N, Río J, Tintoré M, et al. Does the Modified Fatigue Impact Scale offer a more comprehensive assessment of fatigue in MS? Mult Scler. 2005;11(2):198–202. https://doi.org/10.1191/1352458505ms1148oa. Medline:15794395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kos D, Kerckhofs E, Carrea I, et al. Evaluation of the Modified Fatigue Impact Scale in four different European countries. Mult Scler. 2005;11(1):76–80. https://doi.org/10.1191/1352458505ms1117oa. Medline:15732270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fernández O, Fernández V, Baumstarck-Barrau K, et al. ; MusiQoL study group of Spain. Validation of the Spanish version of the Multiple Sclerosis International Quality of Life (Musiqol) questionnaire. BMC Neurol. 2011;11(1):127 https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-11-127. Medline:22013975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio (TX): Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sanz J, Perdigón L, Vázquez C. Adaptación española del Inventario para la Depresión de Beck-II (BDI-II): 2. Propiedades psicométricas en población general. Rev Psicol Clínica y Salud. 2003;14(3):249–80 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Webster KE, Wittwer JE, Feller JA. Validity of the GAITRite walkway system for the measurement of averaged and individual step parameters of gait. Gait Posture. 2005;22(4):317–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2004.10.005. Medline:16274913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hochsprung A, Heredia-Camacho B, Castillo M, et al. [Clinical validity of the quantitative gait variables in patients with multiple sclerosis. A comparison of the timed 25-foot walk test and the GAITRite® Electronic Walkway system]. Rev Neurol. 2014;59(1):8–12. Medline:24965925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gouelle A. Use of Functional Ambulation Performance Score as measurement of gait ability: review [review]. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2014;51(5):665–74. https://doi.org/10.1682/JRRD.2013.09.0198. Medline:25333744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schuhfried O, Mittermaier C, Jovanovic T, et al. Effects of whole-body vibration in patients with multiple sclerosis: a pilot study. Clin Rehabil. 2005;19(8):834–42. https://doi.org/10.1191/0269215505cr919oa. Medline:16323382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3rd ed. New York: Academic Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Learmonth YC, Paul L, Miller L, et al. The effects of a 12-week leisure centre-based, group exercise intervention for people moderately affected with multiple sclerosis: a randomized controlled pilot study. Clin Rehabil. 2012;26(7):579–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215511423946. Medline:21984532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Motl RW, Smith DC, Elliott J, et al. Combined training improves walking mobility in persons with significant disability from multiple sclerosis: a pilot study. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2012;36(1):32–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/NPT.0b013e3182477c92. Medline:22333922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Blikman LJ, Huisstede BM, Kooijmans H, et al. Effectiveness of energy conservation treatment in reducing fatigue in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94(7):1360–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2013.01.025. Medline:23399455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Learmonth YC, Dlugonski D, Pilutti LA, et al. Psychometric properties of the Fatigue Severity Scale and the Modified Fatigue Impact Scale. J Neurol Sci. 2013;331(1–2):102–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2013.05.023. Medline:23791482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Thomas PW, Thomas S, Kersten P, et al. One year follow-up of a pragmatic multi-centre randomised controlled trial of a group-based fatigue management programme (FACETS) for people with multiple sclerosis. BMC Neurol. 2014;14(1):109 https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-14-109. Medline:24886398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Carter A, Daley A, Humphreys L, et al. Pragmatic intervention for increasing self-directed exercise behaviour and improving important health outcomes in people with multiple sclerosis: a randomised controlled trial. Mult Scler. 2014;20(8):1112–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458513519354. Medline:24421303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Beckerman H, Blikman LJ, Heine M, et al. ; TREFAMS-ACE study group. The effectiveness of aerobic training, cognitive behavioural therapy, and energy conservation management in treating MS-related fatigue: the design of the TREFAMS-ACE programme. Trials. 2013;14(1):250 https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-14-250. Medline:23938046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Roppolo M, Mulasso A, Gollin M, et al. The role of fatigue in the associations between exercise and psychological health in multiple sclerosis: direct and indirect effects. Ment Health Phys Act. 2013;6(2):87–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhpa.2013.05.002 [Google Scholar]

- 42. Motl RW, Sandroff BM, Suh Y, et al. Energy cost of walking and its association with gait parameters, daily activity, and fatigue in persons with mild multiple sclerosis. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2012;26(8):1015–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1545968312437943. Medline:22466791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sacco R, Bussman R, Oesch P, et al. Assessment of gait parameters and fatigue in MS patients during inpatient rehabilitation: a pilot trial. J Neurol. 2011;258(5):889–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-010-5821-z. Medline:21076978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kalron A, Frid L, Gurevich M. Concern about falling is associated with step length in persons with multiple sclerosis. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2015;51(2):197–205. Medline:24980633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Broekmans T, Roelants M, Alders G, et al. Exploring the effects of a 20-week whole-body vibration training programme on leg muscle performance and function in persons with multiple sclerosis. J Rehabil Med. 2010;42(9):866–72. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-0609. Medline:20878048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rittweger J. Vibration as an exercise modality: how it may work, and what its potential might be. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2010;108(5):877–904. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-009-1303-3. Medline:20012646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sosnoff JJ, Klaren RE, Pilutti LA, et al. Reliability of gait in multiple sclerosis over 6 months. Gait Posture. 2015;41(3):860–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2015.02.006. Medline:25772669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]