Volume-dose constraints for normal tissues play an important role in both minimizing toxicity and preserving organ function in stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT). Parallel tissues, like lung, liver, and kidney parenchyma, are made up of discrete, relatively radiointolerant (damaged at a low dose) functional units that independently and redundantly perform activities like respiration and detoxification. In contrast, serial tissues, like the bowels, airways, nerves, and ducts, have the ability to repair radiation injury aggressively and constitute conduits for transmission, absorption, and secretion. Parallel tissues form organs of various functions and are connected to the body via serially functioning hila. Parallel and serial tissues benefit from different types of radiation dose constraints. In the case of large parallel organs like lung and liver, surgical series have shown that a minimum of approximately one-third of an individual’s total native organ volume must be preserved to perform the organ’s basic bodily function (R. Timmerman, personal communication, 24 Oct 2016). This “critical volume” must be not only spared but have connection to the body through a functioning hilum (ie, not be isolated or disconnected).

According to the American Association of Physicists in Medicine Task Group report 101 (1), “for parallel tissues, the volume—dose constraints are based on a critical volume of tissue that should receive a dose equal to or less than the indicated threshold for the given number of fractions used.” The critical volume must be spared this threshold dose, above which parallel functioning tissue could be disabled, so that the organ continues to have enough functioning tissue to perform its intended purpose. Unlike dose constraints for serial tissues that portray increasing toxicity to a given volume as the dose to that volume increases, parallel tissues can be considered disabled at the threshold dose, and delivering higher doses has no consequence. Whereas sparing increasingly higher dose to serial tissue avoids toxicity, sparing increasingly larger volumes of the threshold dose avoids toxicity for parallel functioning organs.

For some, the application of parallel tissue critical volume constraints for NRG protocols may be a source of confusion. Clarification is therefore warranted. The purpose of this short communication is to explain the origin and application of these constraints, which in the words of the Task Group 101 report “represent, at best, a first approximation of normal tissue tolerance.”

Several of the NRG protocols use the parallel tissue critical volume constraints for the total lungs but somewhat inaccurately describe the threshold doses as “critical volume dose maxima” (2, 3). One constraint limits at least 1500 cc of total lung to less than the specified threshold dose, with an endpoint of maintaining basic lung function (1). A second constraint calls for sparing at least 1000 cm3 of total lung a slightly higher threshold dose, with an endpoint of avoiding pneumonitis (1). In practice, a plan that meets the first threshold constraint by definition meets the second constraint, and only the 1500-cm3 lung constraint for maintaining basic lung function need be assessed.

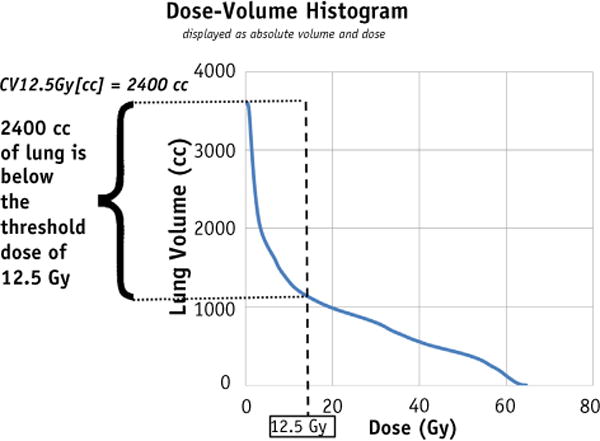

Dose-volume histograms (DVHs) are used to demonstrate compliance with normal tissue tolerances. A hypothetical total lung cumulative DVH is shown in Figure 1 for a 5-fraction SBRT plan whereby both the CT scan and the calculated dose grid encompass the total lung structure. The axes of the figure are displayed in absolute volume and absolute dose. For such a fractionation scheme the 1500-cm3 critical volume threshold dose for lungs from both the Task Group 101 report and the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group 0813 protocol is 12.5 Gy (1, 2).

Fig. 1.

A cumulative dose-volume histogram for total lung from a hypothetical 5-fraction stereotactic body radiation therapy treatment. In this example the threshold dose is 12.5 Gy, the total lung volume is 3600 cm3, and the volume receiving ≥12.5 Gy is 1200 cm3. The complementary volume, CV12.5 Gy[cc], is 2400 cm3.

A user can demonstrate that the critical volume parameter is met using the cumulative DVH and a 3-step process. First, locate the critical volume threshold dose on the abscissa, and use the curve to find the volume of tissue at this dose on the ordinate axis. In Figure 1 the DVH shows that approximately 1200 cm3 of lung receives a dose of ≥12.5 Gy. Second, from the Y intercept of the curve the total lung volume is found to be 3600 cm3. Finally, identify the volume of lung below the threshold dose as 2400 cm3 (3600–1200 cm3). Because this is more than the stated 1500-cm3 critical volume, the plan meets the minimum critical volume constraint designed to preserve lung function.

The complementary volume and dose to complementary volume were introduced in a publication by Mayo et al (4) as components of a standardized DVH nomenclature to improve communication of critical volume and other dose constraints. The complementary volume metric describes the volume of tissue receiving the indicated dose or less. For the hypothetical case shown in Figure 1, “CV12.5 Gy [cc]” is the volume of tissue that receives no more than 12.5 Gy. This is by definition the 2400-cm3 value we already extracted from the DVH. Critical volume parameters can be directly interpreted as the minimum allowed complementary volumes for the indicated threshold dose.

The more conventional DVH volume metrics describe the volume of tissue receiving the indicated dose or higher. For example, V12.5 Gy [%] would be the percent volume of tissue that receives at least 12.5 Gy. These conventional metrics are most familiar to clinicians and may be the only ones available for performing plan optimization. If the conventional DVH nomenclature is preferred, compliance with the critical volume constraint can be assessed with the help of a simple calculation. The percent volume of tissue receiving the threshold dose must meet the criteria:

| (1) |

where Vthreshold dose[%] is the volume that receives the stated threshold dose or higher, Vtotal is the total volume of tissue in the parallel organ considered, and Vcritical is the critical volume appropriate for the treated patient. In the above example for a 5-fraction SBRT plan, the V12.5 Gy [%] should therefore be less than 58%. Calculated Vthreshold dose[%] results that are ≤0% indicate that the critical volume constraint cannot be achieved because the total organ volume is insufficient.

As proposed earlier, for large, parallel organs like the lungs and liver, one-third of their total native organ volume should be spared any radiation injury. This critical volume concept has been used to preserve organ function in many SBRT clinical studies. When treating small lung lesions the critical volume limit is rarely approached. In liver SBRT it is more common to treat a larger fractional volume of the organ, and the concept has proven useful in guiding dose escalation (5,6). The critical volume of an individual organ may warrant further refinement to account for other inherent factors, such as patient sex. Table 1 displays distributions of the lung and liver volumes for males and females (aged ≥21 years) from a University of Michigan cohort of approximately 900 structures as contoured on treatment plans (C. Mayo, unpublished results, 14 Nov 2016). In that cohort, lung and esophagus plans were used for lung volumes and liver plans for liver volumes. The average of ratios for female/male volumes was 0.75 ± 0.08, demonstrating that patient sex may be an important consideration when determining critical structure volumes. Although the volumes in the table do not reflect native volumes from a healthy subject, they may aid the clinician in interpreting where a particular patient falls relative to the average. If a patient has previously lost organ volume, one-third of the diminished remaining volume may be too little for function. In such cases it would be prudent to always spare a minimum critical volume based on the expected total volume of the healthy organ. In the absence of such data, Table 1 may be helpful in guiding the clinical decision (eg, for a female patient of average size, one-third of the median total lung volume from Table 1 could be used to determine that at least 940 cm3 of lung should be spared any radiation injury).

Table 1.

Median lung and liver volumes, as well as the 50% and 90% CIs, for males and females from a cohort of radiation therapy patients

| Structure (no. of structures) | Sex | Volume (cm3)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower 90% CI | Lower 50% CI | Median | Upper 50% CI | Upper 90% CI | ||

| Lung (217) | Female | 1206 | 2218 | 2817 | 3535 | 4503 |

| Lung (223) | Male | 2107 | 2964 | 3757 | 4744 | 6220 |

| Liver (157) | Female | 863 | 1167 | 1359 | 1682 | 2532 |

| Liver (294) | Male | 971 | 1388 | 1672 | 1995 | 2846 |

Abbreviation: CI = confidence interval. Data from reference 8.

In summary, plans can be evaluated for their compliance with the lung critical volume parameter by either: (1) direct extraction of a complementary volume from the DVH; or (2) a calculation of the Vthreshold dose[%] as described in Equation 1. When considering lungs a plan only needs to meet the more restrictive of the 2 critical volume parameters.

The concept of critical volume is important for conserving the function of parallel organs after ablative radiation therapy. It provides a treatment safeguard by protecting a functional volume of tissue, especially in the face of additional treatment complications, such as previous surgeries and dose escalation. It is used in combination with all other protocol-specific dose constraints. Only functional tissue should be included in the critical structure volume. The metric is unaffected by which target volume (gross tumor volume, clinical target volume, or internal target volume) is excluded from the total organ volume definition because all of these structures receive a dose much higher than the critical volume threshold dose. Future NRG SBRT protocols will provide additional guidance on the application of minimal critical volumes.

Acknowledgments

This article was supported by National Cancer Institute grants U24CA180803 and U10CA180868, as well as a State of Pennsylvania CURE grant.

M.M. reports grants from Varian Medical Systems and grants from the National Institutes of Health outside the submitted work. I.J.C. reports grants from Varian Medical Systems and Philips Health Care, outside the submitted work. C.S.M. reports a grant from Varian Medical Systems. C.R. reports grants and personal fees from Varian, grants from Elekta, personal fees from ViewRay, personal fees from DFINE, and other from Radialogica, outside the submitted work. R.D.T. reports grants from the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Benedict SH, Yenice KM, Followill D, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy: The report of AAPM task group 101. Med Phys. 2010;37:4078–4101. doi: 10.1118/1.3438081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bezjak A, Bradley J, Gaspar L, et al. Seamless phase I/II study of stereotactic lung radiotherapy (SBRT) for early stage, centrally located, NSCLC in medically inoperable patients. RTOG 0813 Broadcasts. 2014:1–75. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Videtec G, Singh A, Chang J, et al. A randomized phase II study comparing 2 stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) schedules for medically inoperable patients with stage I peripheral non-small cell lung cancer. RTOG 0915 Broadcasts. 2014:1–60. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mayo C, Pisanski TM, Peterson IA, et al. Establishment of practice standards in nomenclature and prescription to enable construction of software and databases for knowledge-based practice review. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2016;6:e117–e126. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schefter TE, Kavanagh BD, Timmerman RD, et al. A phase I trial of stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) for liver metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;62:1371–1378. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weiner AA, Olsen J, Ma D, et al. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for primary hepatic malignancies—report of a phase I/II institutional study. Radiother Oncol. 2016;121:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2016.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]