Abstract

Objective

Despite increased attention to the relation between negative social reactions to intimate partner violence (IPV) disclosure and poorer mental health outcomes for victims, research has yet to examine whether certain types of negative social reactions are associated with poorer mental health outcomes more so than others. Further, research is scarce on potential mediators of this relationship. To fill these gaps, the current study examines whether stigmatizing reactions to IPV disclosure, such as victim-blaming responses and minimizing experiences of IPV, are a specific type of negative social reaction that exerts greater influence on women’s depressive symptoms than general negative reactions, such as being angry at the perpetrators of IPV. We also examine avoidance coping as a key mediator of this relationship.

Methods

A cross sectional correlational study was conducted to examine these relationships. Participants were 212 women from an urban northeast community who indicated being physically victimized by their male partner in the past six months.

Results

Findings from a multiple regression analysis showed that stigmatizing reactions, not general negative reactions, predicted women’s depressive symptoms. In addition, a multiple mediation analysis revealed that avoidance coping strategies, but not approach coping strategies, significantly accounted for the relationship between stigmatizing social reactions and women’s depressive symptoms.

Conclusions

Findings have implications for improving support from informal and formal sources and subsequently, IPV exposed women’s psychological well-being.

Keywords: intimate partner violence, stigma, social reactions, disclosure, depressive symptoms, coping

Women exposed to intimate partner violence (IPV) are at higher risk for elevated depressive symptoms and major depressive disorder than women not exposed to IPV, with 9%-28% of depressive symptomatology attributed to IPV exposure (Beydoun, Beydoun, Kaufman, Lo, & Zonderman, 2012; Golding, 1999). Extant literature suggests that societal stigmatization embedded in negative social reactions to IPV also may contribute to women’s depressive symptoms (Sylaska & Edwards, 2014; Edwards, Dardis, Sylaska, & Gidycz, 2015). Women who disclose experiences of IPV to informal support networks (e.g., family and friends) encounter both positive and negative reactions to their disclosure (Sylaska & Edwards, 2014; Trotter & Allen, 2009). However, studies have yet to examine whether stigmatizing reactions to IPV disclosure, defined as negatively valenced reactions that discredit and devalue women who experience IPV, are a particular type of negative social reaction associated with women’s depressive symptoms more so than general negative reactions, such as a disclosure recipient’s expressed anger at the perpetrator. Further, given social psychological evidence that stigmatizing reactions may trigger avoidance coping responses (Miller & Major, 2000; Swim & Thomas, 2006), we examine whether stigmatizing reactions to IPV disclosure activate avoidance coping strategies, and in turn, contribute to women’s depressive symptoms. Therefore, the goal of the present study is twofold: 1) to examine whether stigmatizing reactions to IPV disclosure uniquely predict women’s depressive symptoms above and beyond the effect of general negative reactions; and 2) to examine whether avoidance coping strategies rather than approach coping strategies (e.g., problem-solving and social support responses) mediate the potential relationship between stigmatizing reactions and women’s depressive symptoms.

A Case For Examining IPV-Related Stigma

A growing body of literature has begun to conceptualize experiences of IPV within a stigma framework (Overstreet & Quinn, 2013; Eckstein, 2015; Murray, Crowe, & Brinkley, 2015; Murray, Crowe, & Overstreet, 2015). Stigmatization involves societal labeling of difference that is rooted in devaluation and linked to stereotyping, status loss, and discrimination in a power context (Goffman, 1963; Link & Phelan, 2001). Societal stigmatization of IPV is related to perceptions of victims as passive, emotionally dependent, having low self-esteem, inherently flawed and weak, and provoking of their own victimization (Overstreet & Quinn, 2013; Harrison & Esqueda, 1999; Eckstein, 2015). These stigmatizing beliefs contribute to rejection, exclusion, and prejudicial attitudes directed toward people who experience IPV (Murray, Crowe, & Overstreet, 2015; Crowe & Murray, 2015). A recent analysis of IPV stigmatization found that those who experience IPV often feel stigmatized by others via blame, discrediting, shame, and exclusion (Murray, Crowe, & Brinkley, 2015). Thus, it was important for the current study to parse out stigmatizing reactions from general negative reactions to understand their effect on women’s depressive symptoms.

Stigmatizing Reactions to Disclosure and Psychological Distress

Disclosing experiences of IPV may be one avenue through which women encounter stigmatization from others. The Disclosure Processes Model (DPM; Chaudoir & Fisher, 2010) is a theoretical model that outlines the dynamic and continuous process of disclosing concealable stigmatized information, such as IPV, to others and provides a framework for understanding the connection between stigmatizing reactions to IPV disclosure and psychological distress. In the DPM, social support is a key factor associated with psychological health outcomes in that supportive reactions to disclosure are linked to positive health outcomes whereas unsupportive reactions are related to psychological distress. The literature on social reactions to IPV disclosure provides support for this aspect of the DPM. For instance, a literature review on IPV disclosure to informal social support members found that positive social reactions to disclosure are related to psychological well-being whereas negative reactions are related to poorer psychological health, including depressive symptoms (Sylaska & Edwards, 2014). Social reactions are typically assessed as positive (e.g., emotional support, tangible support) or negative (e.g., getting angry at perpetrator, victim-blaming) verbal and nonverbal responses to disclosure (Ullman, 2010). However, evidence in the sexual assault literature suggests that there are nuances in negative reactions that may influence psychological well-being. For example, Relyea and Ullman (2013) found that negative reactions to sexual assault disclosure can be distinguished as either “unsupportive acknowledgment” responses (i.e., mixed valenced responses that may be perceived as both healing and hurtful such as distracting victims or getting angry at the perpetrator) and “turning against” responses (i.e., negatively valenced responses that are generally perceived as hurtful, such as victim-blame responses and treating victims differently). In the IPV literature, studies have yet to examine nuances in negative reactions to IPV disclosure and whether they are particularly deleterious for psychological well-being more so than general negative reactions. Although studies typically find that general negative reactions to IPV disclosure are associated with depressive symptoms (see Sylaska & Edwards, 2014, for review), it is less clear whether stigmatizing reactions are driving this effect. We predict that stigmatizing reactions to disclosure that devalue women who experience IPV are particular types of negative reactions that are related to psychological distress. Given evidence that some negative reactions that are not necessarily stigmatizing, such as getting angry at one’s perpetrator, can be perceived as both healing and hurtful (Relyea & Ullman, 2013), we did not make a specific prediction about the relation between general negative reactions and women’s depressive symptoms. Rather, we explore whether these general negative reactions, when separated from stigmatizing reactions, also are associated with women’s depressive symptoms.

Stigmatizing Reactions and Depression: Coping As Potential Mediator

In line with psychological theories on stigma, stress and coping, we also examine whether stigmatizing reactions to IPV disclosure are associated with the types of coping strategies IPV-exposed women use in their relationships, and in turn, their psychological health. Theories on stigma, stress and coping suggest that people use coping strategies to maintain self-esteem, regulate emotions, and meet other social goals, such as to build trust and understanding with others; and to deal with being targets of stigma, prejudice, and discrimination (Lazarus, 2006; Major, Mendes, & Dovidio, 2013; Miller & Major, 2000; Swim & Thomas, 2006; Phelan, Link, & Dovidio, 2008). Coping involves cognitive and behavioral strategies to deal with stressors in one’s environment and is an important process that women actively engage in to preserve their physical and psychological well-being when experiencing IPV (see Waldrop & Resick, 2004, for review). Few studies have examined the relation between social reactions and women’s coping strategies. Of the studies that have, there is evidence that the type of coping strategies women employ to deal with IPV may elicit positive or negative reactions from disclosure recipients (Sullivan et al., 2010). As suggested by Sullivan and colleagues, although it is possible that the type of coping strategy women employ elicit particular social reactions, it also is possible that the type of social reactions women receive influences the types of coping strategies they employ. Theoretical perspectives on stigma suggest that when people experience stigmatization, they may choose coping responses such as avoidance and disengagement, which has costly consequences for psychological health (Swim & Thomas, 2006; Major, Mendes, & Dovidio, 2013). Thus, we examine whether stigmatizing reactions to IPV disclosure are associated with avoidance coping (relative to approach coping) strategies, and in turn, women’s depressive symptoms.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Two hundred and twelve women currently experiencing IPV participated in the “Women’s Relationship Study.” Participants were recruited from an urban community in New England via flyers displayed in various locations such as grocery stores, health clinics, libraries, and hair and nail salons. Women were considered eligible for the study if they were 18 years of age or older, English speaking, had a monthly income of less than $4,200 (determined a priori to control for access to resources associated with income), experienced physical victimization by a male partner with whom they were in a relationship for at least the past 6 months, and had contact with that partner at least twice a week with no more than 2 weeks apart within the past month. Measures assessing participants’ IPV, mental health, and other psychosocial factors were administered via one-on-one, face-to-face interviews conducted by trained Masters or Doctoral level research associates. Participants were debriefed, remunerated $50 and provided with a list of community resources upon completion of study interview. The home institution’s Institutional Review Board approved study procedures.

Measures

Social Reactions

Stigmatizing reactions and negative reactions were assessed using the 48-item Social Reactions Questionnaire (SRQ; Ullman, 2000). The SRQ consists of positive and negative social reactions to women’s disclosure of sexual assault. We adapted the SRQ in the current study to assess social reactions to women’s disclosure of IPV in their intimate relationships. Of the 48 items, 26 assess negative reactions to disclosure; however, many of the items in this subscale may be considered a negative social reaction but not stigmatizing (e.g., “People you told about the abuse in your relationship expressed so much anger at the perpetrator that you had to calm them down.”). To discern stigmatizing reactions from negative reactions, experts in stigma from the discipline of psychology were identified from the literature. Two experts agreed to serve as content reviewers and were asked to evaluate items that specifically reflected stigmatizing reactions to disclosure of IPV victimization from the list of negative social reactions. Of the 26 items, the raters agreed that 11 items were stigmatizing social reactions (k = .73). The raters disagreed on 3 social reactions. An additional stigma expert identified from the literature, with a particular research focus on stigma and disclosure, provided ratings on these items and 1 item was retained. The final 12 stigmatizing reaction items are listed in Table 1 (α = .86). The remaining 14 items reflected general negative reactions (α = .78). Responses were rated on a scale from 0 (never) to 4 (always). Items were summed with higher scores representing greater stigmatizing/negative reactions to disclosure.

Table 1.

Women’s experiences of stigmatizing and general negative reactions to IPV disclosure (N=212)

| Stigmatizing Social Reactions | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Told you that you could have done more to prevent this experience from occurring. | 118 (55.7%) |

| Told you to stop talking about it. | 90 (42.5%) |

| Minimized the importance or seriousness of your experience. | 81 (38.2%) |

| Said they feel you’re tainted by this experience. | 77 (36.3%) |

| Made you feel like you didn’t know how to take care of yourself. | 70 (33.0%) |

| Treated you differently in some way than before you told them that made you uncomfortable. | 68 (32.1%) |

| Treated you as if you were a child or somehow incompetent. | 62 (29.2%) |

| Told you that you were irresponsible or not cautious enough. | 54 (25.5%) |

| Avoided talking to you or spending time with you. | 51 (24.1%) |

| Acted as if you were damaged goods or somehow different now. | 49 (23.1%) |

| Told you that you were to blame or shameful because of this experience. | 44 (20.8%) |

| Pulled away from you. | 39 (18.4%) |

|

| |

| General Negative Reactions | |

|

| |

| Told you to go on with your life. | 193 (91.0%) |

| Told you to stop thinking about it. | 161 (75.9%) |

| Said they knew how you felt when they really did not. | 157 (74.1%) |

| Expressed so much anger at the perpetrator that you had to calm them down. | 147 (69.3%) |

| Distracted you with other things. | 146 (68.9%) |

| Wanted to seek revenge on the perpetrator. | 139 (65.6%) |

| Have been so upset that they needed reassurance from me. | 130 (61.3%) |

| Told others about your experience without your permission. | 123 (58.0%) |

| Made decisions or did things for you | 122 (57.5%) |

| Focused on their own needs and neglected yours. | 119 (56.1%) |

| Tried to discourage you from talking about the experience. | 108 (50.9%) |

| Tried to take control of what you did or decisions you made. | 98 (46.2%) |

| Said they feel personally wronged by your experience. | 93 (43.9%) |

| Encouraged you to keep the experience a secret. | 88 (41.5%) |

Coping

The Coping Strategies Indicator (CSI; Amirkhan, 1990) was used to assess three domains of specific coping strategies: avoidance (e.g., avoided being with people in general, daydreamed about better times), problem-solving (e.g., brainstormed all possible solutions before deciding what to do), and social support (e.g., confided fears and worries to a friend or a relative). The CSI is a 33-item self-report measure in which each subscale is composed of 11 items that are summed to create a subscale score. In the current study, participants were instructed to describe a conflict with their intimate partner in the past six months that was important to them and caused them to worry. The items assessed the coping strategies participants used to deal with this relationship conflict. Participants rated each item using a 3-point Likert-type scale (1 = not at all, 2 = a little, 3 = a lot). The CSI demonstrated adequate reliability for the avoidance coping (α = .74), problem-solving (α = .83), and social support (α = .94) subscales. Items were summed with higher scores representing more frequent use of each type of coping strategy.

Depressive Symptoms

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). Participants reported the frequency with which they experienced 20 depressive symptoms over the last six months (e.g., “I could not shake off the blues even with help from my family or friends.”). Responses were rated on a scale from 0 (rarely or none of the time) to 3 (most or all of the time). Items were summed to create a total score (α = .91). Higher scores indicate greater frequency of depressive symptoms.

IPV

Three scales were used to assess women’s experiences of physical, sexual, and psychological IPV victimization in the past 6 months.

Physical IPV

Physical IPV was assessed using 12-items from the Conflict Tactics Scale-2 (CTS-2; Straus, Hamby, & Warren, 2003). These items measured both moderate and severe physical aggression from a partner (e.g., “My partner threw something at me that could hurt.”). Response options were: never, once, twice, 3-5 times, 6-10 times, 10-20 times, and more than 20 times in the past 6 months. These response categories were recoded according to procedures outlined by Straus et al. (i.e., 4 = 3-5; 8 = 6-10; 15 = 10-20; 25 = > 20). Items were summed (α = .89) with higher scores indicative of greater physical victimization.

Sexual IPV

Sexual IPV was assessed using the 10-item Sexual Experiences Survey (SES; Koss & Oros, 1982). An example item is “has your partner tried to make you have sex by using force, like slapping or pushing, or by threatening to use force?” The same response options that were used for the physical IPV scale were used to measure sexual IPV. The sexual IPV score was dichotomized given the positive skew in the number of women who reported sexual IPV; thus, participants who responded that sexual victimization occurred once or more on any of the 10 items were assigned a ‘1’ (otherwise ‘0’).

Psychological IPV

Psychological IPV was assessed using the 48-item Psychological Maltreatment of Women Inventory (PMWI; Tolman, 1989). An example item is “my partner insulted me or shamed me in front of others.” Items were rated on a scale from 1 (never) to 5 (very frequently). Items were summed to create a total score (α = .95). Higher scores indicate greater psychological victimization.

Sociodemographics

Participants reported their age, race/ethnicity, income, highest level of education, employment status, relationship status, and relationship duration.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated to describe sociodemographic characteristics of the sample. Bivariate correlation analysis was conducted among the variables of interest. To understand whether stigmatizing reactions to IPV disclosure were a unique predictor of depressive symptoms beyond the effects of general negative reactions, a simultaneous multiple regression analysis was conducted with depressive symptoms as the dependent variable, controlling for psychological IPV, physical IPV, and sexual IPV.

To understand the mediating effect of stigmatizing reactions on depressive symptoms via coping strategies we conducted a multiple mediator analysis with stigmatizing reactions as a predictor of depressive symptoms and the three types of coping responses as mediators: social support coping, problem-solving coping, and avoidance coping. We also included physical, sexual, and psychological IPV as control variables in this analysis because they were significantly correlated with depressive symptoms at the bivariate level. Age, income, and education were not significantly correlated with depressive symptoms and were not included as covariates.

Results

Participants were between 18 and 58 years of age (M = 36.63, SD = 10.45). Approximately 67.0% of women identified as Black, 20.3% identified as White, 8.5% identified as Latina, and 4.2% identified as multiracial. A majority of the sample had a high school education or equivalent (73.6%) and reported being unemployed (65.1%), with a median yearly income of $9,600 (ranging from $0-$48,000). Approximately 45% of women reported being unmarried but cohabitating with their partner, 32.1% indicated they were dating their partner but not cohabitating, and 14.2% were married. Women were in a relationship with their current partners between 1 month and 31 years with an average of 6.47 years (SD = 6.37). The mean depression severity score was 24.90 (SD = 12.02). All women in the sample reported physical and psychological IPV, and 60.2% of women experienced some form of sexual IPV in the past six months.

Table 1 shows the 12 items that were identified as stigmatizing reactions and the remaining 14 general negative reactions listed in the Social Reactions Questionnaire. In this table, we report the percentage of women in our sample that experienced each type of reaction. If women reported never experiencing a reaction, the item was coded as 0 and all other responses were coded as 1. The most common stigmatizing reaction women reported was being told that they could have done more to prevent IPV from occurring and the least common reaction was pulling away from the victim once she disclosed experiences of IPV. The most common general negative reaction was the victim being told to go on with her life and the least common reaction was the victim being encouraged to keep the IPV secret. Stigmatizing reactions generally consisted of responses that devalued women who disclosed IPV and general negative reactions involved greater focus on the disclosure recipient rather than the victim, the disclosure recipient trying to take control of situation, or the disclosure recipient engaging in strategies to distract women from their victimization.

Table 2 shows the means, standard deviations, and correlations for the study variables. Stigmatizing social reactions to IPV disclosure were positively correlated with negative social reactions, depression severity, avoidance coping, psychological, and sexual IPV but was negatively correlated with income.

Table 2.

Correlations, means, and standard deviations among study variables (N = 212)

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Stigmatizing Reactions | 8.09 | 6.99 | — | ||||||||||

| 2. Negative Reactions | 8.73 | 5.98 | 72** | — | |||||||||

| 3. Social Support Coping | 21.97 | 6.43 | .10 | .16* | — | ||||||||

| 4. Problem-Solving Coping | 26.69 | 4.44 | −.02 | .03 | .27** | — | |||||||

| 5. Avoidance Coping | 24.00 | 4.36 | .25** | .21** | .04 | .16* | — | ||||||

| 6. Depressive Symptoms | 24.90 | 12.02 | .23** | .18* | .08 | .03 | .45** | — | |||||

| 7. Psychological IPV | 127.30 | 34.83 | .24** | .31** | .08 | .10 | .36** | 46** | — | ||||

| 8. Physical IPV | 35.20 | 47.05 | .13 | .22** | −.03 | −.03 | .22** | .43** | .51** | — | |||

| 9. Sexual IPV | 56% | .27** | .26** | .08 | −.02 | .18** | .23** | .28** | .24** | — | |||

| 10. Income | 13304.82 | 10389.85 | − 23** | −.26** | −.06 | −.04 | −.22** | −.05 | −.06 | −.20** | −.01 | — | |

| 11. Education | 12.09 | 1.56 | −.14 | −.23** | −.03 | −.02 | −.17* | .01 | −.04 | −.01 | .14* | 34** | — |

| 12. Age | 36.63 | 10.45 | .09 | .03 | −.01 | .18** | .05 | .08 | .16* | .00 | .15* | −.05 | −.01 |

Note.

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01.

Social Reactions and Depression Severity

A simultaneous multiple regression analysis was conducted to examine the effect of stigmatizing and general negative social reactions on depressive symptoms (see Table 3). Psychological (β= .36, p = .00) and physical IPV (β= .23, p = .00) were significant predictors of depressive symptoms. As predicted, stigmatizing reactions to IPV disclosure (β= .17, p = .05) was a unique predictor of depressive symptoms but general negative reactions to IPV disclosure was not. These variables accounted for 31% of the variance in depressive symptoms, F (5, 166) = 14.92, p = .00.

Table 3.

Effect of Stigmatizing Reactions vs. General Negative Reactions on Depressive Symptoms

| Predictor | β | t |

|---|---|---|

| Psychological IPV | .36** | 4.68** |

| Physical IPV | .23** | 3.12** |

| Sexual IPV | .10 | 1.41 |

| General Negative Reactions | −.14 | −1.57 |

| Stigmatizing Reactions | .17* | 2.00* |

Note. Betas represent standardized coefficients;

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01.

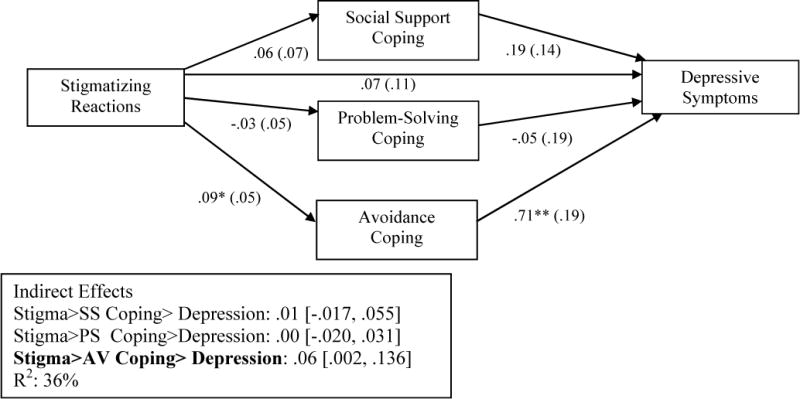

Examining the Potential Mediating Role of Coping Strategies

Next we conducted a multiple mediator analysis to examine whether stigmatizing reactions to IPV disclosure are associated with women’s depressive symptoms via three coping strategies (avoidance coping, social support coping, and problem-solving coping) using the PROCESS SPSS macro (Hayes, 2013). This analysis allows us to estimate direct and indirect effects of the relationships shown in Figure 1, which shows the results of this analysis. Significance of indirect effects was tested using bootstrapping with 95% confidence intervals (represented in brackets below) and 10,000 re-samples. The indirect effect of stigmatizing reactions on depressive symptoms through avoidance coping was the only significant indirect effect in the model, indirect effect = .06 [.002, .136]. Stigmatizing reactions to IPV disclosure were positively associated with avoidance coping strategies, which in turn were related to greater depressive symptoms. Stigmatizing reactions to disclosure were not significantly associated with other forms of coping, such as problem-solving (indirect effect = .00 [−.020, .031]) and social support coping (indirect effect = .01 [−.017, .055]), and these coping strategies were not significantly related to depressive symptoms.

Figure 1. Multiple Mediator Model.

Note. Analysis controlled for physical, sexual, and psychological IPV. Coefficients are unstandardized. Standard errors are in parentheses. Confidence intervals for indirect effects are in brackets. *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

Discussion

The present study examined the unique contribution of stigmatizing reactions (vs. general negative reactions) to IPV disclosure to women’s depressive symptoms. Moreover, we examined whether three types of coping strategies (i.e., problem-solving coping, social support coping, and avoidance coping) may account for this relationship. Findings provide support that there are nuances in negative social reactions that may differentially influence women’s mental health outcomes. Specifically, we found evidence that stigmatizing social reactions that discredit and devalue women who experience IPV, such as victim-blaming responses and minimization of IPV, are associated with depressive symptoms whereas general negative reactions, such as being angry with the perpetrator of IPV, were not related to women’s depressive symptoms, after controlling for IPV victimization. Further, of the three types of strategies women may engage in to cope with experiences of relationship conflict, only avoidance coping strategies accounted for the relation between stigmatizing social reactions and women’s depressive symptoms. We found evidence that stigmatizing social reactions were associated with engagement in avoidance coping strategies to deal with relationship conflict, which in turn was related to greater depressive symptoms.

Our findings advance research on negative reactions to IPV disclosure by identifying stigmatizing reactions as a specific response that is related to poorer mental health. These findings come at a time when research on social reactions has increasingly begun to use the Social Reactions Questionnaire to assess both positive and negative responses to IPV disclosure (DePrince et al., 2014; Edwards et al., 2015; Sullivan et al., 2010). Given this emerging research, in addition to recent evidence in the sexual assault literature that there are nuances in negative reactions (Relyea & Ullman, 2013), it was important for the current study to examine whether certain types of negative reactions to IPV disclosure were related to poorer mental health. Although stigmatizing reactions and general negative reactions were positively correlated with women’s depressive symptoms at the bivariate level, when we included both as predictors of depressive symptoms, only stigmatizing reactions remained a significant predictor of depressive symptoms. However, it is worthy to note that though the relationship of general negative reactions to depression is non-significant, the absolute value of the coefficient suggests that certain negative reactions may have the potential to be helpful. This certainly warrants investigation in future research. It was important for our study to focus on reactions that discredited and devalued those who experience IPV (Overstreet & Quinn, 2013; Murray et al., 2015; Goffman, 1963). Through this lens, stigma experts identified 12 out of 26 negative reactions that fit this definition. Interestingly, we found that the most commonly experienced stigmatizing reactions women reported were being told that they could have done more to prevent IPV from occurring, that they should stop talking about experiences of IPV, that one is tainted by experiences of IPV, and that disclosure recipients’ minimized the importance or seriousness of their IPV experiences. Stigmatizing reactions to IPV disclosure and negative reactions to sexual assault disclosure may overlap in a number of ways, such as victim-blame, shame, and discrediting, but also may have important differences, such that victims of IPV may be treated as if they’re incompetent, have their experiences of IPV minimized, and - an unexplored aspect in the current work – be told to leave the abuser (Edwards et al., 2015; Edwards, Dardis, & Gidycz, 2012; Trotter & Allen, 2009). Future research is needed to examine the effect of stigmatizing reactions to IPV disclosure on mental health outcomes, such as post-traumatic stress symptoms. Moreover, research should explore nuances in general negative reactions by accounting for whether women’s perceptions of these reactions as either healing, hurtful, or both play a role in influencing their mental health and coping strategies.

These findings also highlight how stigmatizing social reactions to IPV disclosure may be linked to women’s depressive symptoms through disengagement strategies to deal with IPV. We found that avoidance coping strategies, rather than approach coping strategies mediated the relationship between stigmatizing social reactions and women’s depressive symptoms, after controlling for the effects of physical, sexual, and psychological IPV. This finding is consistent with the literature on stigma and coping (Major, Mendes, & Dovidio, 2013; Miller & Major, 2000; Swim & Thomas, 2006). This literature suggests that avoidance coping and disengagement are possible reactions to experiences of stigma, which subsequently have negative consequences for mental and physical health through diminished resources to deal with stigma and lowered ability to self-regulate emotions (Hatzenbuehler, Phelan, & Link, 2013). We focused on the consequences of stigma and avoidance coping on depressive symptoms but, other areas ripe for examination include understanding the effect of IPV-related stigmatization on physical health outcomes and whether experiences of stigmatizing reactions to IPV disclosure influence how one chooses to disclose these experiences to others in the future.

In the current study, we did not ask participants about the source of the stigmatizing reactions to IPV-disclosure. However, research suggests that people who experience negative reactions to disclosure can experience these reactions from informal (e.g., family and friends) and formal (e.g., health care providers) sources (Sylaska & Edwards, 2014; Trotter & Allen, 2009). Thus, it is important to examine the effect of IPV-stigmatization on the individual and also the context of the interpersonal interaction. Utilization of health care services is one interpersonal context that has critical implications for understanding the consequences of IPV-related stigmatization, particularly for women of color. For example, Rodríguez and colleagues (2009) found that lack of utilization of health care services by ethnically diverse IPV survivors included worries about stigmatization in the form of being negatively judged and mistreated by health care providers, beliefs that IPV should not be discussed with others, and cultural stigmatization around seeking out mental health care. These IPV-related stigma concerns also were compounded by language barriers, desire to protect their partners from discriminatory treatment from others, financial concerns, fears of deportation, and concerns about appearing weak for accessing health services. A majority of our sample identified as women of color and may have been concerned about stigmatization related to other aspects of their identity. Thus, it is worth examining in future studies how IPV-related stigma intersects with other marginalized aspects of women’s identities to affect their health outcomes and health care utilization. Further, our findings may inform interventions on health care utilization by addressing the ways in which health care providers support IPV-exposed women when they seek health care.

Although findings of the current work extend research on negative reactions and mental health outcomes among women who have experienced IPV, it is worth noting these findings in the context of the following limitations. First, the present study was a cross-sectional examination of the relation between negative social reactions, coping strategies, and depressive symptoms, which prevents claims of the directionality of these relationships. Future research may be able to address this concern by conducting a longitudinal study. Second, our measure of negative social reactions did not account for the source of negative reactions. Many women in our sample indicated that they experienced victim-blame, silencing, and minimization of IPV by others but the source of these reactions is not known. Knowing the source of stigmatizing reactions might yield a more nuanced approach for understanding negative reactions and the many ways in which they manifest (Trotter & Allen, 2009). Finally, our study examined negative reactions to IPV disclosure in a sample of women where an eligibility requirement for participation was experiencing physical victimization from a male partner in the last 6 months. Thus, our findings may not generalize to other populations such as women who experience IPV in same-sex relationships, women who experience psychological IPV only, or men who experience IPV.

Despite these limitations, the findings of the current study expand on the social reactions IPV literature by providing support for nuances in negative reactions and highlighting avoidance coping strategies as a mediator of the relation between stigmatizing reactions to IPV disclosure and women’s depressive symptoms. These findings point to reactions that discredit and devalue women who experience IPV as detrimental to psychological well-being. Thus, it is necessary for informal and formal supports to provide responses that do not stigmatize women who experience IPV. Further, if stigmatizing reactions to IPV disclosure are associated with avoidance coping strategies, interventions may be able to reduce the impact of negative reactions on women’s depressive symptoms by suggesting other ways to cope with negative reactions to IPV disclosure when they occur. In sum, reacting to disclosures of IPV in positive and supportive ways, and not stigmatizing those who disclose, may play a significant role in reducing the psychological distress that women experiencing IPV face.

Acknowledgments

The research described here was supported, in part, by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R03 DA17668; T32DA019426) and that National Institute of Mental Health (T32MH020031).

References

- Amirkhan JH. A factor analytically derived measure of coping: The Coping Strategy Indicator. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;59(5):1066. [Google Scholar]

- Beydoun HA, Beydoun MA, Kaufman JS, Lo B, Zonderman AB. Intimate partner violence against adult women and its association with major depressive disorder, depressive symptoms and postpartum depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Science & Medicine. 2012;75(6):959–975. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudoir SR, Fisher JD. The disclosure processes model: Understanding disclosure decision-making and postdisclosure outcomes among people living with a concealable stigmatized identity. Psychological Bulletin. 2010;136(2):236. doi: 10.1037/a0018193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Smith PH, Thompson MP, McKeown RE, Bethea L, Davis KE. Social support protects against the negative effects of partner violence on mental health. Journal of Women’s Health & Gender-based Medicine. 2002;11(5):465–476. doi: 10.1089/15246090260137644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe A, Murray CE. Stigma from professional helpers toward survivors of intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse. 2015;6(2):157–179. [Google Scholar]

- DePrince AP, Welton-Mitchell C, Srinivas T. Longitudinal predictors of women’s experiences of social reactions following intimate partner abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2014:0886260513520469. doi: 10.1177/0886260513520469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunham K, Senn CY. Minimizing negative experiences: Women’s disclosure of partner abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2000;15(3):251–261. [Google Scholar]

- Eckstein JJ. IPV Stigma and its Social Management: The Roles of relationship-type, abuse-type, and victims’ sex. Journal of Family Violence. 2015:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards KM, Dardis CM, Gidycz CA. Women’s disclosure of dating violence: A mixed methodological study. Feminism & Psychology. 2012;22(4):507–517. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards KM, Dardis CM, Sylaska KM, Gidycz CA. Informal social reactions to college women’s disclosure of intimate partner violence associations with psychological and relational variables. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 30(1) 2015:25–44. doi: 10.1177/0886260514532524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flicker SM, Cerulli C, Swogger MT, Talbot NL. Depressive and posttraumatic symptoms among women seeking protection orders against intimate partners: Relations to coping strategies and perceived responses to abuse disclosure. Violence against Women. 2012;18(4):420–436. doi: 10.1177/1077801212448897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Prentice Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Golding JM. Intimate partner violence as a risk factor for mental disorders: A meta-analysis. Journal of Family Violence. 1999;14(2):99–132. [Google Scholar]

- Goodkind JR, Gillum TL, Bybee DI, Sullivan CM. The impact of family and friends’ reactions on the well-being of women with abusive partners. Violence against Women. 2003;9(3):347–373. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison LA, Esqueda CW. Myths and stereotypes of actors involved in domestic violence: Implications for domestic violence culpability attributions. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 1999;4:129–138. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Phelan JC, Link BG. Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(5):813–821. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. New York: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Oros CJ. Sexual Experiences Survey: a research instrument investigating sexual aggression and victimization. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1982;50(3):455. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.50.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS. Stress and emotion: A new synthesis. Springer Publishing Company; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Levendosky AA, Bogat GA, Theran SA, Trotter JS, von Eye A, Davidson WS., II The social networks of women experiencing domestic violence. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2004;34(1–2):95–109. doi: 10.1023/b:ajcp.0000040149.58847.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology. 2001;27:363–385. [Google Scholar]

- Littleton H, Horsley S, John S, Nelson DV. Trauma coping strategies and psychological distress: a metaDanalysis. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2007;20(6):977–988. doi: 10.1002/jts.20276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major B, Mendes WB, Dovidio JF. Intergroup relations and health disparities: A social psychological perspective. Health Psychology. 2013;32(5):514. doi: 10.1037/a0030358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CT, Major B. Coping with stigma and prejudice. The social psychology of stigma. 2000:243–272. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell RE, Hodson CA. Coping with domestic violence: Social support and psychological health among battered women. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1983;11(6):629–654. doi: 10.1007/BF00896600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CE, Crowe A, Brinkley J. The stigma surrounding intimate partner violence: A cluster analysis study. Partner Abuse. 2015;6(3):320–336. [Google Scholar]

- Murray CE, Crowe A, Overstreet NM. Sources and components of stigma experienced by survivors of intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2015 doi: 10.1177/0886260515609565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overstreet NM, Quinn DM. The intimate partner violence stigmatization model and barriers to help seeking. Basic and applied social psychology. 2013;35(1):109–122. doi: 10.1080/01973533.2012.746599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan JC, Link BG, Dovidio JF. Stigma and prejudice: One animal or two? Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67(3):358–367. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied psychological measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Relyea M, Ullman SE. Unsupported or turned against: Understanding how two types of negative social reactions to sexual assault relate to postassault outcomes. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2013 doi: 10.1177/0361684313512610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez M, Valentine JM, Son JB, Muhammad M. Intimate partner violence and barriers to mental health care for ethnically diverse populations of women. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2009;10(4):358–374. doi: 10.1177/1524838009339756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Warren WL. The Conflict Tactics Scales handbook. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan TP, Schroeder JA, Dudley DN, Dixon JM. Do differing types of victimization and coping strategies influence the type of social reactions experienced by current victims of intimate partner violence? Violence against women. 2010;16(6):638–657. doi: 10.1177/1077801210370027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swim JK, Thomas MA. Responding to everyday discrimination: A synthesis of research on goal-directed, self-regulatory coping behaviors. Stigma and group inequality: Social psychological perspectives. 2006:105–126. [Google Scholar]

- Sylaska KM, Edwards KM. Disclosure of intimate partner violence to informal social support network members: A review of the literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2014;15(1):3–21. doi: 10.1177/1524838013496335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolman RM. The development of a measure of psychological maltreatment of women by their male partners. Violence and victims. 1989;4(3):159–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trotter JL, Allen NE. The good, the bad, and the ugly: Domestic violence survivors’ experiences with their informal social networks. American journal of community psychology. 2009;43(3–4):221–231. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9232-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE. Psychometric characteristics of the Social Reactions Questionnaire: A measure of reactions to sexual assault victims. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2000;24(3):257–271. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE. Talking about sexual assault: Society’s response to survivors. American Psychological Association; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Waldrop AE, Resick PA. Coping among adult female victims of domestic violence. Journal of Family Violence. 2004;79(5):291–302. [Google Scholar]