Abstract

Synchronous multiple endocrine gland metastasis caused by small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is rare. A patient was investigated for primary cancer because of suspected brain metastasis on computed tomography (CT). Baseline 18F–fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET)‐CT was positive in the lung and multiple endocrine glands (right thyroid, right breast, pancreatic body, right adrenal gland, and left ovary). Histopathology confirmed small cell lung cancer. The patient's symptoms were alleviated after chemotherapy and brain radiotherapy. Follow‐up PET‐CT revealed that some of the lesions had disappeared and some had reduced in size. This rare case of multiple endocrine gland metastases from SCLC suggests that whole body PET‐CT is a useful tool to detect rare/asymptomatic metastases.

Keywords: Case report, endocrine gland, fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography, metastasis, small‐cell lung carcinoma

Introduction

Preferential metastatic sites of small cell lung cancer (SCLC) are the brain, liver, adrenal glands, bones, and marrow.1 The thyroid, breast, ovary, pancreas, stomach, intestine, and pituitary gland are relatively rare sites of metastasis.2, 3, 4, 5 Synchronous multiple endocrine gland metastasis is rarely diagnosed with traditional imaging techniques such as ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging. Herein, we report a rare case of simultaneous multiple endocrine gland metastasis revealed by 18F–FDG (18F‐fluorodeoxy‐glucose) positron emission tomography (PET)‐CT.

Case Report

A 58‐year‐old Chinese woman underwent physical examination and CT at another hospital in July 2012, which revealed brain lesions highly suggestive of brain metastases with edema. She was a heavy smoker (50 packs/year for 30 years) and had a rural occupation, but no significant personal or familial medical history. She reported chronic dizziness, dyspnea on exertion, an occasional productive cough with clear phlegm, and a month of chronic back pain (starting in June 2012). She had not received any treatment for these symptoms.

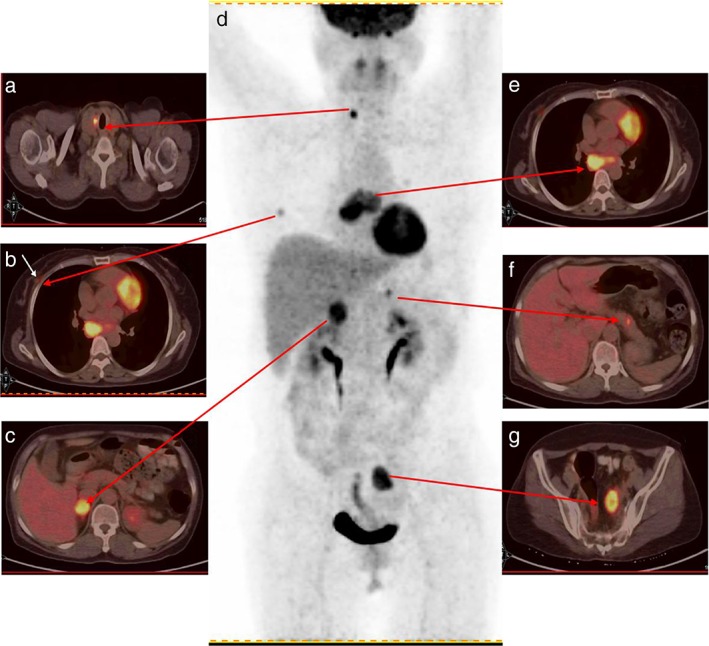

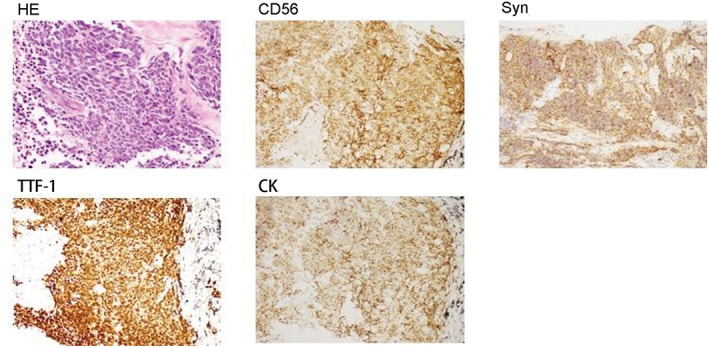

A whole body baseline 18F–FDG PET‐CT scan (Biograph 16HR, Siemens, Germany) was performed one week after brain CT demonstrated high FDG uptake in multiple endocrine glands (the body and brain were separately scanned with PET‐CT because of resolution), including a 1.5 cm lesion in the right thyroid, the maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) was 6.2, and a 1.1 cm lesion in the right breast (SUVmax = 3.2), a 0.9 cm lesion in the pancreatic body (SUVmax = 5.1), a 2.9 cm mass in the right adrenal gland (SUVmax = 7.1), and a 2.8 cm mass in the left ovary (SUVmax = 7.2) were detected (Fig 1). Multiple suspicious brain metastatic lesions with edema were also observed, measuring 1–2 cm in diameter (SUVmax = 4.5). A high FDG uptake lesion (SUVmax = 7.1) was revealed by PET‐CT in the inferior lobe of the right lung hilus beside the mediastinum. Transbronchial lung biopsy performed 10 days after PET‐CT revealed SCLC (Fig 2). Six cycles of chemotherapy with cisplatin and irinotecan and whole brain radiotherapy (30 Gy) were administered. Seven months later, follow‐up revealed greatly improved performance status (Fig 3). Further chemotherapy was suspended.

Figure 1.

Baseline positron emission tomography‐computed tomography (PET‐CT): high uptake nodules in the (a) right thyroid (maximum standardized uptake value [SUVmax] = 6.2), (b) right breast (SUVmax = 3.2), and (c) right adrenal gland (SUVmax = 7.1). (d) PET maximum intensity projection of the patient. (e) The right lung lobe hilus high‐uptake nodule (SUVmax = 7.1). (f) The pancreas high‐uptake nodule (SUVmax = 5.1). (g) The left ovary high‐uptake nodule (SUVmax = 7.2).

Figure 2.

Hematoxylin–eosin (HE) staining and immunohistochemistry of lung transbronchial biopsy specimens (magnification 200×).

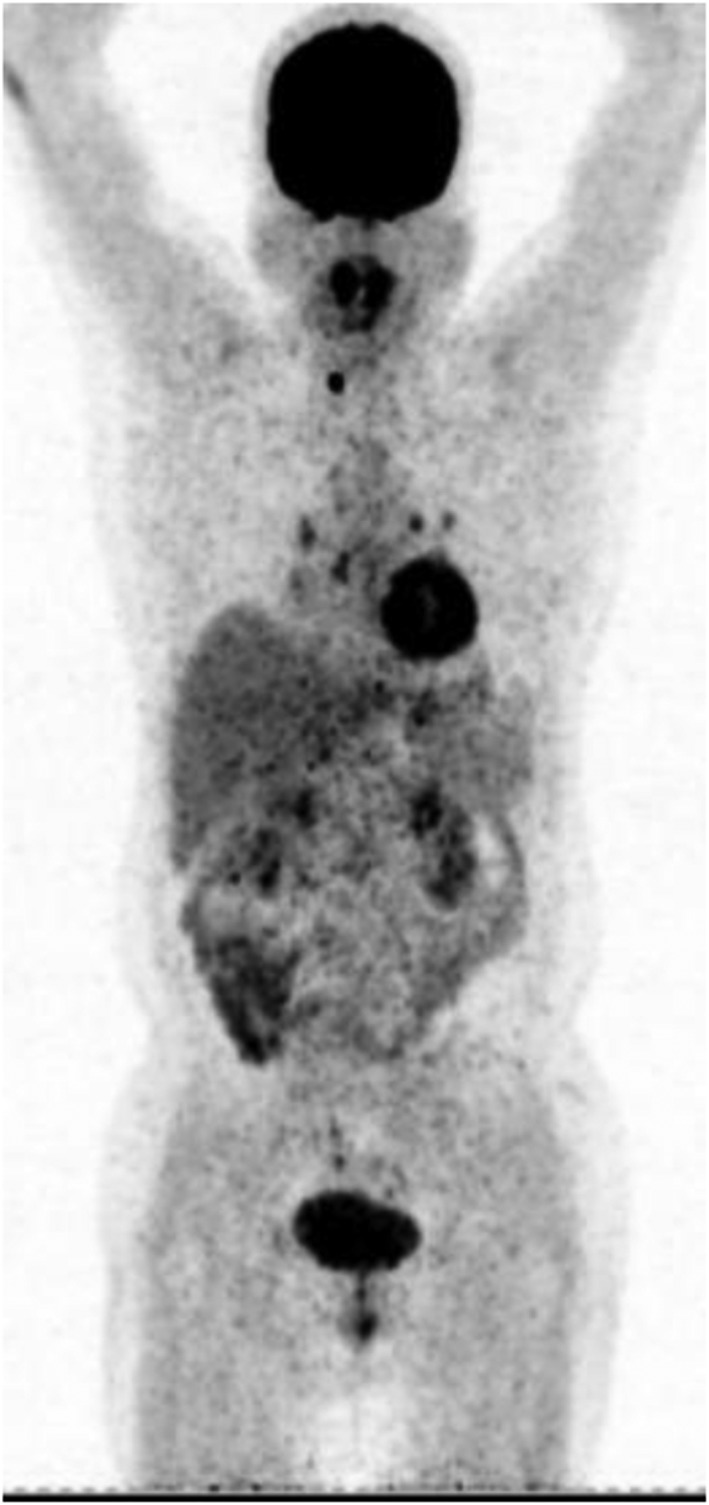

Figure 3.

Follow‐up positron emission tomography‐computed tomography (PET‐CT) examination after chemotherapy. High FDG uptake lesions in the right lung lobe hilus had reduced, and all previous lesions in the right breast, right adrenal gland, and left ovary had disappeared. Only the right thyroid nodule was still present.

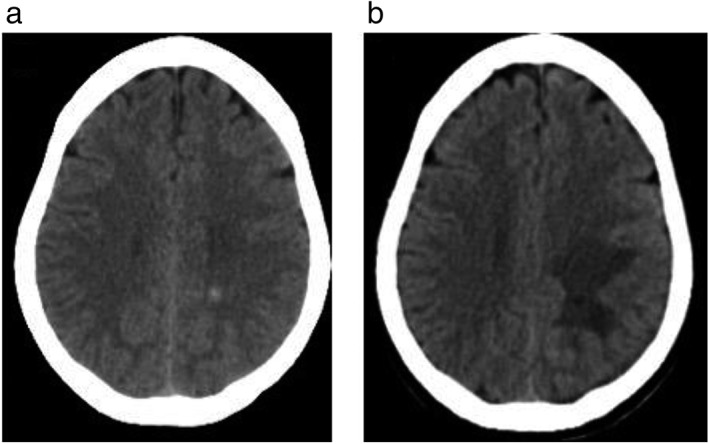

One year later, follow‐up PET‐CT revealed that all previous lesions in the right breast, pancreatic body, right adrenal gland, and left ovary had disappeared, and the right lung hilus lesion had reduced, suggesting a good response to chemotherapy. The brain nodules had also reduced (Fig 4). The lesion in the right thyroid gland appeared unchanged but was proven benign by ultrasound and fine needle aspiration. The patient died two years after the initial PET‐CT examination.

Figure 4.

Brain lesions suspected as brain metastases. Computed tomography (a) before radiotherapy showed left centrum semiovale metastasis, and (b) after radiotherapy showed that the lesions had reduced in size.

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee and was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. The participants provided written informed consent.

Discussion

A review of 31 articles published between 1989 and 2013 showed only 41 independent cases of primary lung carcinoma metastasis to the breast, including only 10 cases of SCLC. Breast metastasis from SCLC is often positive for CD56, CGA, Syn, NSE, and TTF‐1, and negative for ER, PR, and HER2. Nevertheless, the breast lesion was not sampled in the present case and we cannot completely exclude the possibility of two synchronous primary cancers. PET‐CT could be helpful to differentiate primary from metastatic lesions. In this case, the lung cancer was larger with a higher 18F‐FDG uptake, as well as mediastinum lymph node metastasis, while the breast nodule was smaller with a lower FDG uptake.

Ovarian malignant lesions are generally primary carcinomas and less frequently metastases from extra‐gynecological tumors.6 Ovarian metastasis from lung cancer represents only 2–4% of all ovarian metastatic lesions.6 Because of completely different treatment methods and prognosis, distinguishing between a primary and metastatic ovarian neoplasm is critical to administer the correct therapeutic strategy. Primary ovarian neoplasms often present as large complex masses accompanied by increased CA125 levels and metastatic signs to the greater omentum and peritoneum. Therefore, the characteristics of our case, including an oval mass with a smooth surface in the left ovary, unilateral 18F‐FDG uptake, without intra‐abdominal spread, suggested this lesion was likely a metastatic cancer, later confirmed by follow‐up PET‐CT results after chemotherapy.

Metastases to the pancreas are rare, found by autopsy in 3–12% of patients with advanced cancer.7 Lung cancer is the most frequent type of malignancy causing pancreatic metastasis (18–27%), followed by renal cell, breast, colorectal, and hepatobiliary tract cancers.7 SCLC is the most frequent cytological type of lung cancer that metastasizes to the pancreas (10%).8 Many patients with pancreatic metastases remain asymptomatic, as in the present case. Therefore, the disease is only diagnosed at an advanced stage. Early recognition of pancreatic metastasis in lung cancer patients is important because the patient then has a chance to receive the appropriate therapy and avoid serious complications, such as acute pancreatitis and obstructive jaundice.5 Recognition of pancreatic metastasis in patients with lung cancer is important for adequate patient management. The patient in this case had undergone abdomen CT scanning but the pancreatic lesion was not detected.

Fluorodeoxyglucose uptake information can guide biopsy. Despite the fact that the diagnosis of endocrine gland metastasis in this case was solely based on PET‐CT, PET‐CT was probably sufficient to accurately identify the metastases, based on the uptake of the lesions, as reported by a previous study.9

Because there were multiple lesions on PET‐CT and because the primary SCLC had been identified, the suspected metastatic lesions were not all biopsied to confirm the diagnosis. Because of brain metastases, primary SCLC, and poor prognosis, additional diagnostic procedures were deemed unnecessary. CT scans and magnetic resonance imaging from the first hospital were not available to the authors.

In conclusion, this rare case of multiple endocrine gland metastases from SCLC suggests that whole body PET‐CT is a useful tool to detect rare/asymptomatic metastases. We report this case to increase recognition of rare metastases from SCLC.

Disclosure

No authors report any conflict of interest.

Acknowledgment

We thank the patient's family for their collaboration.

References

- 1. van Meerbeeck JP, Fennell DA, De Ruysscher DK. Small‐cell lung cancer. Lancet 2011; 378: 1741–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mirrielees JA, Kapur JH, Szalkucki LM et al Metastasis of primary lung carcinoma to the breast: A systematic review of the literature. J Surg Res 2014; 188: 419–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fujiwara A, Higashiyama M, Kanou T et al Bilateral ovarian metastasis of non‐small cell lung cancer with ALK rearrangement. Lung Cancer 2014; 83: 302–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Akamatsu H, Tsuya A, Kaira K et al Intestinal metastasis from non‐small‐cell lung cancer initially detected by 18F‐fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Jpn J Radiol 2010; 28: 684–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fridley J, Adams G, Rao V et al Small cell lung cancer metastasis in the pituitary gland presenting with seizures and headache. J Clin Neurosci 2011; 18: 420–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cengiz H, Yildiz S, Kaya C, Senyürek E, Ekin M, Yasar L. Ovarian metastasis from lung cancer: A rare entity. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol 2013; 2013: 378438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sato M, Okumura T, Kaito K et al Usefulness of FDG‐PET/CT in the detection of pancreatic metastases from lung cancer. Ann Nucl Med 2009; 23: 49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zheng Y, Gao Q, Fang W, Xu N, Zhou J. Gastrointestinal bleeding due to pancreatic metastasis of non‐small cell lung cancer: A report of two cases and a literature review. Oncol Lett 2015; 9: 2041–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dijkman BG, Schuurbiers OC, Vriens D et al The role of (18)F‐FDG PET in the differentiation between lung metastases and synchronous second primary lung tumours. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2010; 37: 2037–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]