Abstract

Tuberous sclerosis complex-associated renal angiomyolipoma (TSC-RAML) confers a high risk of bleeding and even mortality. However, data on TSC-RAML in Chinese pedigrees is extremely lacking. The present study aimed to investigate its clinical and genetic characteristics by obtaining a detailed medical history from 6 probands and their family members, and reassessing blood tests, computed tomography and renal dynamic imaging examinations that were conducted in the TSC-RAML patients. The TSC1/TSC2 mutation was detected in 2 families. A total of 3 TSC-RAML patients underwent partial nephrectomy due to a high bleeding risk, and the other 2 were treated with everolimus. The remaining 6 TSC-RAML patients received no clinical intervention and only had clinical follow-uzp. It was found that nearly 37% (18/49) were TSC patients, with the mean ± standard deviation diagnostic age being 34.22±17.73 years old in the 6 pedigrees, 61% (11/18) of whom suffered from TSC-RAML. In the 11 TSC-RAML patients, the maximum diameter of the tumor ranged between 1.20 and 32.50 cm (mean ± standard deviation, 11.48±8.40 cm), the unilateral glomerular filtration rate ranged between 27.20 and 60.10 ml/min (mean ± standard deviation, 42.55±9.73 ml/min), the serum creatinine level ranged between 40.00 and 90.00 µmol/l (mean ± standard deviation, 64.84±16.15 µmol/l) and the hemoglobin concentration ranged between 76.00 and 140.00 g/l (mean ± standard deviation, 107.73±21.04 g/l). Pathogenic mutations of TSC1 (c.733C>T) and TSC2 (c.788_789insC) were detected in family B and C, respectively, as well as certain non-pathogenic mutations, with the maximum diameter of TSC-RAML being 0 cm and 10.3 cm in the two patients from family B and 16 cm and 1.2 cm in the two patients from family C. Expression of phosphorylated-mechanistic target of rapamycin was determined in the TSC-RAML tissues by immunohistochemistry. The maximum diameter of the tumor decreased by 4.90 and 5.30 cm, respectively, in the 2 patients treated with everolimus after 3 months. In conclusion, TSC cannot be easily diagnosed due to its variable characteristics. Growth of TSC-RAML may increase the bleeding risk and reduce the level of hemoglobin, but it does not greatly affect renal function. Individual differences in tumor dimensions existed even with the same pathogenic mutation, except for cases of coexistent non-pathogenic mutations. Everolimus treatment appears to be able to significantly reduce the size of TSC-RAML.

Keywords: tuberous sclerosis complex, angiomyolipoma, kidney, mechanistic target of rapamycin, gene mutation

Introduction

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), an autosomal dominant disorder of multiple organ systems involving the brain, lung, kidney, skin and other organs (1), presents with a great variety of clinical manifestations (2,3). Multiple and bilateral renal angiomyolipomas are found in ~70–90% of adult patients with TSC as reported by O'Callaghan et al and Rakowski et al (4,5), tend to grow slowly and often result in spontaneous bleeding when tumor diameter is beyond 4 cm (1). Although TSC can seriously affect the health of patients and cause a heavy economic burden (6,7), it is difficult for a physician or surgeon, particularly those with less experience, to make a definitive diagnosis, not to mention to provide effective management in a timely manner, when patients present with atypical organ involvement or few systemic clinical features (8,9). The clinical diagnostic criteria of TSC includes 11 major and 6 minor features, and the diagnosis is difficult when patients' symptoms do not fully align with the definitive diagnosis, which requires at least two major features or one major feature with two or more minor features (2). In these cases, the family medical history may be useful. However, to the best of our knowledge, the published literature on TSC genealogy has been mostly comprised of case reports, and the maximum number of family members was three in a single study (10,11), revealing that data on TSC genealogy is lacking.

The present study performed retrospective detailed analysis of the characteristics of clinical genetics, imaging studies, laboratory tests and treatments in 6 patients with TSC-associated renal angiomyolipoma (RAML) and their family members. The study focused on renal involvement, which can significantly affect the lives of TSC patients and leave 25–50% at risk of hemorrhage (12), and aimed to provide experiences of the diagnosis and treatment of TSC-RAML for use in future clinical practice.

Materials and methods

General patient information

Within the 49 family members of the 6 pedigrees, there were 18 TSC patients, including 11 TSC-RAML patients, 5 TSC patients without RAML and 2 TSC patients without abdominal imaging data. The 6 probands and their family members were all referred to the Urological Surgery Clinic (Zhengzhou, China) between January 2012 and December 2014. Of these, 1 family was from The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University (Zhengzhou, Henan, China) and the remaining 5 were from Peking Union Medical College Hospital (Beijing, China). In total, 7 out of the 11 TSC-RAML patients had a history of intermittent abdominal pain. Once informed consent had been obtained from each patient, individual data and the family history were collected in detail. The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital (Beijing, China).

Clinical data of patients

All TSC patients underwent blood routine examinations and blood biochemistry analysis to assess the degree of anemia and the function of the liver and kidneys. Computed tomography and renal dynamic imaging were conducted in the TSC-RAML patients to reevaluate the current situation with regard to renal involvement and unilateral renal function. The 2 TSC patients without abdominal imaging data refused to undergo the radiological examinations. A TSC1/2 gene mutation was detected in 2 families when blood samples were sent for high-throughput sequencing analysis to the Beijing Genomics Institute (Shenzhen, China) in accordance with the patients' wishes. Partial renal resection was performed in 3 TSC-RAML patients due to the high risk of bleeding with growth of the large renal lesions, which were relatively independent and superficial. Another 2 TSC-RAML patients were treated with mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor (everolimus, 10 mg/day, in a single oral dose, for one year).

Immunohistochemical staining

The TSC-RAML specimens were fixed in 10% formalin solution for 24 h at 4°C in the refrigerator, underwent dehydration, transparent and wax immersion, and were sliced into 5 µm sections. Dewaxing and rehydration: each of xylene I and II for 20 min, 100% alcohol for 10 min, the each of 95, 80 and 70% alcohol for 5 min. Sections were incubated in 3% hydrogen peroxide at 37°C for 10 min to block and inactivate the endogenous peroxidase, and boiled in 0.01 M citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 15 min at 95°C, then naturally cooled over 20 min for antigen retrieval. Hematoxylin and eosin staining procedures were performed at room temperature for 60 min, and then observed under a light microscope at magnification, ×100, followed by immunohistochemical staining procedures: The primary antibodies were: anti-p-mTOR (Ser2448; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA; cat. no. sc-101738; 1:250), anti-S6K1 (phospho T389; Abcam, Cambridge, UK; cat. no. ab126818; 1:500) and anti-eIF4EBP1 (phospho T70; Abcam; cat. no. ab75831; 1:200), and the horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled secondary antibody was goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (Novoprotein, Summit, NJ, USA; cat. no. AB501; 1:50). To each section, 50 µl of each of the primary antibody (incubated for 1 h at 37°C) or secondary antibody (incubated for 30 min at 37°C), HRP-labeled streptavidin working solution (concentration: 0.5%) and diaminobenzidine solution (concentration: 0.01%) were added sequentially. The reaction was terminated with distilled water once brown granules were observed using a light microscope at magnification, ×100. The hematoxylin staining was then performed again lasting 30 sec, and then put in double distilled water lasting 5 min.

Results

Clinical characteristics in pedigrees

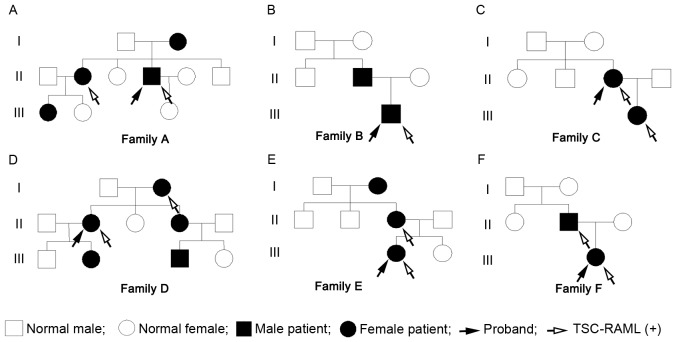

Pedigree charts of the 6 families are shown in Fig. 1, including the 6 probands and 12 family members (female, 13; male, 5). The mean diagnostic age was 34.22±17.73 years (Table I). Within the 18 TSC patients, 15 cases were consistent with the definite diagnosis criteria, and the remaining 3 were associated with possible diagnosis criteria (13). The TSC-RAML patients accounted for ~61% (11/18) of the subjects, excluding the 2 cases without abdominal imaging. The 6 probands were all patients with TSC-RAML (female, 4; male, 2), with the diagnostic age ranging between 9 and 39 years (mean, 27.00±11.45 years). With regard to family location, 5 were from rural areas and 1 was from an urban area.

Figure 1.

(A-F) Pedigree charts of the 6 families. The pedigree charts include 18 TSC patients (female, 13; male, 5), of which, 11 patients have been diagnosed with TSC-RAML (female, 8; male, 3). The 6 probands are all TSC-RAML patients, of which, just the patient from family CII is the first generation with a pathogenic mutation, and the remaining 5 are inherited from the previous generation. TSC-RAML, tuberous sclerosis complex-associated renal angiomyolipoma.

Table I.

Characteristics of the 18 TSC patients.

| Pedigree | Patient | Accord with definite diagnosis (yes/no) | Age at TSC diagnosis, years | Age at RAML diagnosis, years | Maximum diameter of TSC-RAML, cm | Urban/rural patient location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family A | 1 | Yes | 61 | Unknown | Unknown | Urban |

| 2 | Yes | 42 | 31 | 12.7 | Urban | |

| 3a | Yes | 36 | 28 | 3.8 | Urban | |

| 4 | No | 19 | – | – | Urban | |

| Family B | 1 | Yes | 43 | – | – | Rural |

| 2a | Yes | 9 | 14 | 10.3 | Rural | |

| Family C | 1a | Yes | 34 | 34 | 16 | Rural |

| 2 | Yes | 12 | 12 | 1.2 | Rural | |

| Family D | 1 | Yes | 60 | 56 | 5.9 | Rural |

| 2a | Yes | 39 | 37 | 10.4 | Rural | |

| 3 | No | 35 | – | – | Rural | |

| 4 | Yes | 16 | – | – | Rural | |

| 5 | No | 12 | – | – | Rural | |

| Family E | 1 | Yes | 68 | Unknown | Unknown | Rural |

| 2 | Yes | 45 | 43 | 7.2 | Rural | |

| 3a | Yes | 24 | 22 | 32.5 | Rural | |

| Family F | 1 | Yes | 41 | 27 | 16.3 | Rural |

| 2a | Yes | 20 | 21 | 10 | Rural |

Probands of TSC-RAML. TSC-RAML, tuberous sclerosis complex-associated renal angiomyolipoma.

Imaging and laboratory examinations

The unilateral glomerular filtration rate in each of the 11 TSC-RAML patients ranged between 27.20 and 60.10 ml/min (mean, 42.55±9.73 ml/min, normal, 40~60 ml/min), the serum creatinine level ranged between 40.00 and 90.00 µmol/l (mean, 64.84±16.15 µmol/l; normal, male: 44–132 µmol/l, female: 70–106 µmol/l), the hemoglobin concentration ranged between 76.00 and 140.00 g/l (mean, 107.73±21.04 g/l; normal, male: 120–160 g/l, female: 110–150 g/l) and the maximum diameter of the TSC-RAMLs ranged between 1.20 and 32.50 cm (mean, 11.48±8.40 cm). In families B and C, the maximum diameters of the tumors of the proband and their family members were 10.3 and 0 cm, and 16 and 1.2 cm, respectively, and the pathogenic gene mutations were TSC1 c.733C>T and TSC2 c.788_789insC, respectively. There were also a number of non-pathogenic mutations (Table II). The systolic blood pressure ranged between 70.00 and 138.00 mmHg (mean, 108.00±20.59 mmHg; normal, <120 mmHg), and the diastolic blood pressure ranged between 40.00 and 83.00 mmHg (mean, 64.91±13.01 mmHg; normal, <80 mmHg).

Table II.

TSC gene mutations in two families.

| Pedigree | Patient | Gene | Mutation | Pathogenicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family B | Proband | TSC1 | c.733C>T | Pathogenic |

| TSC1 | c.2626-4_-3insTT | Non-pathogenic | ||

| TSC2 | c.5161-9C>T | Non-pathogenic | ||

| TSC2 | p.Asp1734Asp | Non-pathogenic | ||

| Family member | TSC1 | c.733C>T | Pathogenic | |

| Family C | Proband | TSC2 | c.788_789insC | Pathogenic |

| TSC1 | c.1631G>A | Non-pathogenic | ||

| Family member | TSC2 | c.788_789insC | Pathogenic | |

| TSC2 | c.856A>G | Non-pathogenic |

TSC, tuberous sclerosis complex.

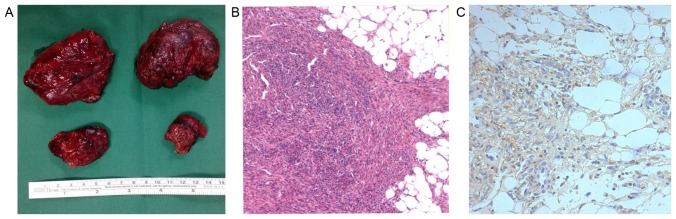

Surgical treatment and immunohistochemical staining

Due to a high risk of bleeding, as well as the relatively isolated and protruding nature of the RAMLs, 3 patients underwent a partial nephrectomy by means of open surgery, preserving the normal renal tissue as much as possible. Pathological results showed a large number of smooth muscle cells and fat cells, as well as certain malformed blood vessels and aneurysms in part of the visual field. Immunohistochemistry determined the positive expression of p-mTOR in the TSC-RAML tissues, particularly in the cells of the vascular wall (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Surgical specimens and pathological results of TSC-RAML. (A) The 4 specimens of TSC-RAML tissue are from 1 patient who underwent open surgery; the maximum diameter of the resected masses is ~5 cm; (B) Hematoxylin and eosin staining: A large number of spindle smooth muscle cells and plump fat cells can be observed in the TSC-RAML tissue (magnification, ×100). (C) Immunohistochemical staining: Brown granules in the TSC-RAML tissue indicate the positive expression of phosphorylated-mechanistic target of rapamycin (magnification, ×100). TSC-RAML, tuberous sclerosis complex-associated renal angiomyolipoma.

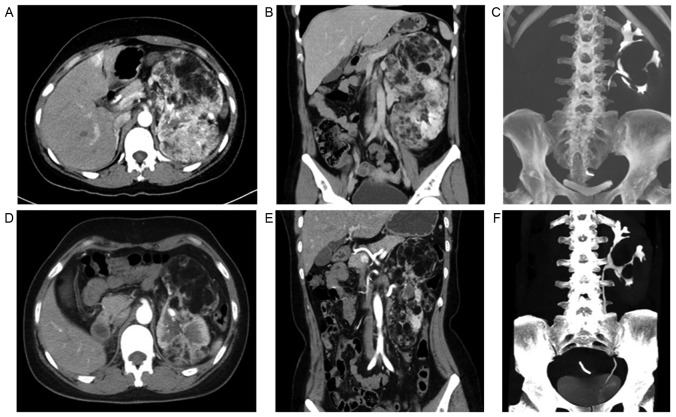

Everolimus treatment

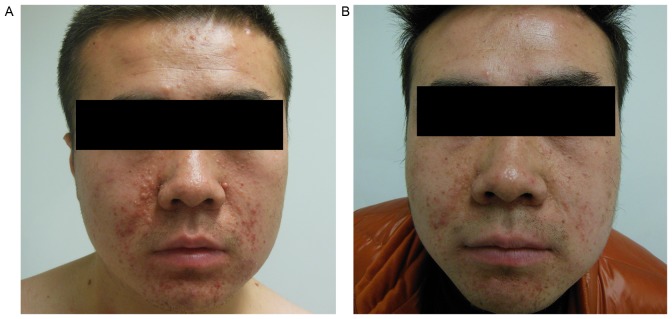

Until the time of data collection, 2 of the TSC-RAML patients had been treated with everolimus (10 mg/day, in a single oral dose) for 3 months. The intermittent abdominal pain disappeared completely, and the abdominal circumference of 1 patient was reduced by >3 cm compared with the initial data 3 months ago (measured while fasting in the morning). The maximum diameter of the TSC-RAML decreased by 4.90 and 5.30 cm, respectively, in the 2 patients, and the morphology of the renal collecting system became more regular when compared with the baseline data (Fig. 3). Changes to the facial angiofibromas in 1 patient are shown in Fig. 4, from which it can be observed that the angiofibromas had become much flatter, smaller and lighter in color compared with those prior to therapy.

Figure 3.

Changes in TSC-RAML prior to and following treatment with everolimus. (A) The sagittal image in computed tomography prior to treatment (baseline data). (B) The coronal image in computed tomography prior to treatment (baseline data). (C) The morphology of left renal collecting system prior to treatment (baseline data). (D) The sagittal image in computed tomography following treatment. (E) The coronal image in computed tomography post-treatment. (F) The morphology of the left renal collecting system following treatment. The maximum dimensions of the left RAML decreased from 20.3×9.0×13.5 cm pre-therapy to 15.0×7.0×11.0 cm at 3 months following treatment. The morphology of the left renal collecting system (F) following treatment was more regular and centralized compared with that (C) prior to treatment. The right kidney was removed two years prior to treatment due to acute bleeding of TSC-RAML. TSC-RAML, tuberous sclerosis complex-associated renal angiomyolipoma.

Figure 4.

Changes in facial angiofibromas prior to and following treatment with everolimus. (A) The facial angiofibromas are quite red and markedly convex prior to treatment. (B) The facial angiofibromas are lighter colored and flattened 3 months following treatment.

Discussion

TSC is caused by pathogenic mutation of the tumor-suppressing genes, TSC1 or TSC2, which encode hamartin and tuberin, respectively, and normally down-regulate mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1). Once a pathogenic mutation occurs in either TSC1 or TSC2, the dysfunction of hamartin-tuberin complex will terminate its negative regulation of the activation of mTORC1 and its downstream regulators, resulting in TSC (14,15).

TSC can be diagnosed by either genetic or clinical diagnostic criteria according to the updated recommendations of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference (11). However, although experts have agreed that identification of a pathogenic mutation in either TSC1 or TSC2 is an independent diagnostic criterion, 10–30% of TSC patients have no pathogenic mutation, which means that a normal result does not exclude TSC (13,16,17). Additionally, due to the relatively high medical costs and technical constraints, the use of clinical diagnostic criteria, including 11 major features and 6 minor features, remain the main diagnostic method.

However, the majority of TSC-RAML patients, who may have marked clinical signs and symptoms, including recurrent abdominal pain, reduced appetite, weight loss, an abdominal mass or progressive abdominal expansion, are not diagnosed as early as possible or treated in a timely manner. In the present study, the mean diagnostic age of the 6 probands was 27 years, and that of the 18 TSC patients was ~34 years, suggesting that diagnosis and treatment occurs relatively late. The main causes of this may be as follows: i) The relative lack of knowledge about TSC, leading to a non-comprehensive understanding of the rare and variable nature of the disease by doctors; ii) a relatively remote place of residence, resulting in limited access to good health resources; iii) the extremely variable characteristics of TSC, meaning that it cannot easily be identified when patient symptoms do not fully accord with the definitive diagnosis: Two major features or one major feature with two or more minor features (13). In the present study, 5 families were from rural areas, and 16.67% of TSC patients met the possible diagnostic criteria, with a final definite diagnosis benefiting from the contribution of the family history.

TSC is an autosomal dominant genetic disease, and the genetic diversity of the current cohort is shown in Fig. 1. There were 18 TSC patients in the 6 pedigrees, accounting for only ~37% of subjects, and 11 with TSC-RAML, accounting for only ~22%. Within the TSC patients, TSC-RAML cases account for ~61%, which is similar to the data (55–80%) reported by De Waele et al (18). The maximum diameters of TSC-RAML also varied widely among individuals in the present study, ranging from 1.2 to 32.50 cm (mean, 11.48±8.40 cm), even amongst those with the same pathogenic mutation. Results of genetic testing in families B and C revealed that the proband and their family members not only had the same pathogenic mutation, but that they also had other different non-pathogenic mutations, which could not lead to nucleotide changes, but may interfere with gene transcription and protein synthesis, thereby affecting the activity of the mTOR signaling pathway and promoting or inhibiting cell proliferation.

Although lesions are multiple and bilateral in almost all TSC-RAML patients, with relatively large diameters that result in pelvicaliceal deformation and renal contour disappearance, it appears that there is little impact on renal function. In the 11 TSC-RAML patients, the mean serum creatinine was nearly 65 µmol/l, and the mean unilateral renal glomerular filtration rate was ~42 ml/min; these were in the normal range. Even for the patient with the largest TSC-RAML (diameter, 32.50 cm), the serum creatinine level was 40.00 µmol/l, and the unilateral renal glomerular filtration rate was 27.20 ml/min (left) and 60.10 ml/min (right), respectively. Nevertheless, the concentration of hemoglobin gradually decreases with the increasing diameter of the renal lesions; for example, it was 75.00 g/l in the patient with the largest TSC-RAML, which is lower than the mean level of 111.19±25.04 g/l. This results from the intermittent bleeding as the renal lesions grow, since such patients present mostly with a history of recurrent abdominal pain, and even multiple aneurysm formation and intralesional hemorrhage in RAMLs have been confirmed in certain patients by imaging.

As the clinical features of TSC-RAML are bilateral and multiple in nature, and as the volume of RAMLs tends to increase gradually with age (19), renal function should be preserved as much as possible in the treatment process. Therapies such as selective arterial embolization, partial nephrectomy and ablation are not preferred as the first-line therapies (20), unless the patients are at an extremely high risk of bleeding, or have experienced repeated spontaneous bleeding or active bleeding with ineffective conservative treatment. Only 3 patients in the present study underwent partial nephrectomy due to the high risk of bleeding, and the pathological results showed the positive expression of p-mTOR, indicating the excessive activation of the mTOR signaling pathway, which also has been confirmed in TSC brain and skin lesions (21,22). Bissler et al (23) reported preliminary results of the clinical efficacy and safety of everolimus, which is an inhibitor of the mTOR signaling pathway, on RAML in patients with TSC or sporadic lymphangiomyomatosis, having demonstrated a significant reduction in AML volume and safety for oral administration (23). A sustained reduction in RAML volume with continued everolimus treatment was also confirmed in later results (24). In the present study, following treatment with everolimus for 3 months, the maximum diameter of TSC-RAML in the 2 patients decreased by 4.90 and 5.30 cm, respectively, the intermittent abdominal pain disappeared completely and the facial angiofibromas improved.

In conclusion, as a rare autosomal dominant genetic disease, TSC cannot be easily diagnosed or treated in a timely manner due to its variability, the relative lack of TSC data and the level of local medical services. The growth of TSC-RAML may increase the risk of bleeding and reduce the level of hemoglobin, but it does not greatly affect renal function. Individual differences in TSC-RAML exist even in cases with the same pathogenic gene mutation, probably as a result of the presence of other non-pathogenic gene mutations that do not encode proteins but regulate the translation process. The results of the present study suggested that p-mTOR expression was positive in TSC-RAML, as determined by immunohistochemical analysis, and the results of previous clinical trials and the present study also demonstrated the promising clinical efficacy of everolimus. Therefore, mTOR inhibitors may be an optimal therapy for treating TSC, allowing surgical intervention to be used only for cases with a high risk of bleeding or unexpected hemorrhage.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Y. Cai, from the Department of Urology, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College (Beijing, China), for support by providing the medical records of the TSC-RAML patients in the present study.

Glossary

Abbreviation

- TSC-RAML

tuberous sclerosis complex-associated renal angiomyolipoma

References

- 1.Curatolo P, Bombardieri R, Jozwiak S. Tuberous sclerosis. Lancet. 2008;372:657–668. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61279-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krueger DA, Northrup H International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group, corp-author. Tuberous sclerosis complex surveillance and management: Recommendations of the 2012 international tuberous sclerosis complex consensus conference. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;49:255–265. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosser T, Panigrahy A, McClintock W. The diverse clinical manifestations of tuberous sclerosis complex: A review. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2006;13:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.spen.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Callaghan FJ, Noakes MJ, Martyn CN, Osborne JP. An epidemiological study of renal pathology in tuberous sclerosis complex. BJU Int. 2004;94:853–857. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.05046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rakowski SK, Winterkorn EB, Paul E, Steele DJ, Halpern EF, Thiele EA. Renal manifestations of tuberous sclerosis complex: Incidence, prognosis and predictive factors. Kidney Int. 2006;70:1777–1782. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Demuth D, Nasuti P, Lucchese L, Gray L, Pinnegar A, Magestro M. Economic impact of patients with tuberous sclerosis complex (tsc) in the Uk: A retrospective database analysis in the clinical practice research datalink (Cprd) Value in Health. 2014;17:A137. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2014.03.794. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rentz AM, Skalicky AM, Liu Z, Wheless JW, Dunn DW, Frost MD, Nakagawa J, Magestro M, Prestifilippo J. Tuberous sclerosis complex: A survey of health care resource use and health burden. Pediatr Neurol. 2015;52:435–441. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2014.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kakkar A, Vallonthaiel AG, Sharma MC, Bora G, Panda A, Seth A. Composite renal cell carcinoma and angiomyolipoma in a patient with Tuberous sclerosis: A diagnostic dilemma. Can Urol Assoc J. 2015;9:E507–E510. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.2532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Falsafi P, Taghavi-Zenouz A, Khorshidi-Khiyavi R, Nezami N, Estiar MA. A case of tuberous sclerosis without multiorgan involvement. Glob J Health Sci. 2015;7:124–131. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v7n5p124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xue G, Han X, Ren S, Yue X. An Analysis of 11 Cases of Tuberous Sclerosis from Three Genealogies. Chin J Neuroimmunol and Neurol. 1999;6:249–252. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Y, Gan J, Pu Z, Xu Mm, Wang LF, Li YH, Liu ZG. TSC1 R509X mutation in a chinese family with tuberous sclerosis complex. Neuromolecular Med. 2015;17:202–208. doi: 10.1007/s12017-015-8354-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dixon BP, Hulbert JC, Bissler JJ. Tuberous sclerosis complex renal disease. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 2011;118:e15–e20. doi: 10.1159/000320891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Northrup H, Krueger DA International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group, corp-author. Tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria update: Recommendations of the 2012 international tuberous sclerosis complex consensus conference. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;49:243–254. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tee AR, Manning BD, Roux PP, Cantley LC, Blenis J. Tuberous sclerosis complex gene products, Tuberin and Hamartin, control mTOR signaling by acting as a GTPase-activating protein complex toward Rheb. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1259–1268. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00506-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wataya-Kaneda M. Mammalian target of rapamycin and tuberous sclerosis complex. J Dermatol Sci. 2015;79:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sancak O, Nellist M, Goedbloed M, Elfferich P, Wouters C, Maat-Kievit A, Zonnenberg B, Verhoef S, Halley D, van den Ouweland A. Mutational analysis of the TSC1 and TSC2 genes in a diagnostic setting: Genotype--phenotype correlations and comparison of diagnostic DNA techniques in Tuberous Sclerosis Complex. Eur J Hum Genet. 2005;13:731–741. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Au KS, Williams AT, Roach ES, Batchelor L, Sparagana SP, Delgado MR, Wheless JW, Baumgartner JE, Roa BB, Wilson CM, et al. Genotype/phenotype correlation in 325 individuals referred for a diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis complex in the United States. Genet Med. 2007;9:88–100. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31803068c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Waele L, Lagae L, Mekahli D. Tuberous sclerosis complex: The past and the future. Pediatr Nephrol. 2015;30:1771–1780. doi: 10.1007/s00467-014-3027-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seyam RM, Bissada NK, Kattan SA, Mokhtar AA, Aslam M, Fahmy WE, Mourad WA, Binmahfouz AA, Alzahrani HM, Hanash KA. Changing trends in presentation, diagnosis and management of renal angiomyolipoma: Comparison of sporadic and tuberous sclerosis complex-associated forms. Urology. 2008;72:1077–1082. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DiMario FJ, Jr, Sahin M, Ebrahimi-Fakhari D. Tuberous sclerosis complex. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2015;62:633–648. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruppe V, Dilsiz P, Reiss CS, Carlson C, Devinsky O, Zagzag D, Weiner HL, Talos DM. Developmental brain abnormalities in tuberous sclerosis complex: A comparative tissue analysis of cortical tubers and perituberal cortex. Epilepsia. 2014;55:539–550. doi: 10.1111/epi.12545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan JY, Wang KH, Fang CL, Chen WY. Fibrous papule of the face, similar to tuberous sclerosis complex-associated angiofibroma, shows activation of the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway: Evidence for a novel therapeutic strategy? PLoS One. 2014;9:e89467. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bissler JJ, Kingswood JC, Radzikowska E, Zonnenberg BA, Frost M, Belousova E, Sauter M, Nonomura N, Brakemeier S, de Vries PJ, et al. Everolimus for angiomyolipoma associated with tuberous sclerosis complex or sporadic lymphangioleiomyomatosis (EXIST-2): A multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;381:817–824. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61767-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bissler JJ, Kingswood JC, Radzikowska E, Zonnenberg BA, Frost M, Belousova E, Sauter M, Nonomura N, Brakemeier S, de Vries PJ, et al. Everolimus for renal angiomyolipoma in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex or sporadic lymphangioleiomyomatosis: Extension of a randomized controlled trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;31:111–119. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]