Abstract

In Iran, cardiovascular diseases are the most common causes of death. We aimed to perform a systematic review on the prevalence of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in Iran based on Persian and English papers had been published from 1985 to 2015. Among 267 initially found articles, 142 were excluded; finally, a total number of 40 articles were found relevant which were reduced to 18. Smoking, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and hypercholesterolemia were the most common risk factors for AMI. Premature MI prevalence was high in men, and smoking was the most common risk factor among young people. People in urban areas were more likely to experience AMI than rural people. The prevalence of AMI in Iran is high and has increased in recent years. Therefore, to restrain the rising trend of AMI, it is necessary to make the primary and secondary prevention efforts.

Key words: Acute myocardial infarction, Iran, prevalence, risk factors, systematic review

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) are among the most common causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide[1,2] that account for 35% of global deaths. These diseases lead to complications, significant disability, and reduced productivity putting them on top of costly problems in the health-care system.[3,4] According to the Third Report by the World Health Organization (WHO), 12 million people die annually of CVD worldwide, and it is predicted that until 2020 will reach to 25 million/year.[5] coronary artery disease (CAD) more than any other disease cause morbidity and mortality in developed countries and imposing economic costs. Along with urbanization of developing countries, the prevalence of risk factors for CAD is rapidly increasing in such a way that a major part of the global burden of CAD belongs to low- and middle-income countries where include 85% of whole world population.[6] Primary prevention and appropriate treatment of these diseases have reduced CAD-related mortality in North America and Western Europe in recent decades. However, in the same period, the prevalence of these diseases has increased in Eastern Europe and Asia.[7] As a subtype of CAD, acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is the most common cause of death.[8] In the United States. Approximately, 1–1.5 million people suffer from MI of which approximately 33% die of the disease annually.[9]

More importantly, the disease also affects young men and women. Most studies show that 4%–15% of the patients with AMI are under 45 years old.[1,8,10] In Iran, CVDs are the most common causes of death.[5,11] According to the published statistics in 2009, 3.6 million people in Iran were admitted with diagnosis of a CAD only in hospitals affiliated to the Ministry of Health Care, and Medical education.[9]

Given the high costs of treating these diseases, scientific, and scholarly attitude toward them as well as treatment and control of these diseases would save billions from health-care costs. Therefore, it is a primary requirement to know the epidemiology and risk factors for AMI in any region. Thus, in this review, we examined papers which were published in English and Persian on the epidemiology of AMI risk factors in Iran.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search strategy

A systematic review was performed on the papers which were published between 1991 and 2015 about the prevalence of AMI and its risk factors in Iran. External databases such as PubMed, Scopus, ProQuest, Institute for Scientific Information Web of Science, ScienceDirect, Wiley online library, Springer, Ovid, Cochrane Library, and internal one's including Medlib, Barekat, Magiran, Scientific Information Database, and Ganj and Google scholar were selected. Retrieval of information from different databases was separately performed at 20/8/2015. Information's retrieval was performed by use of the words, “myocardial infarction (MI),” “epidemiology,” “prevalence,” “incidence,” “risk factors,” and “Iran” in the field of advanced search of external databases. Furthermore, these keywords were used in Google search engine in English and Persian equivalent. In the internal databases, some keywords including: “epidemiology of MI,” “prevalence of MI,” and “incidence of MI” and their Persian equivalents were searched.

Furthermore, unofficial sources and reference list of articles were investigated for related articles. Bibliographic information of 267 retrieval articles was transferred to Microsoft Excel worksheet. English title of Persian (original language) articles was replaced by Persian title and duplicate records were deleted. The title of all article were investigated and papers with non-Iranian target population were deleted, 125 articles remained. Then, abstract and full text of articles were studied, and suitable articles were selected by several step.

Criteria for selecting papers

The main criterion for selecting papers in this study was focus of the paper on the prevalence, incidence, and risk factors of MI in Iran. On checking the titles for relevance purposes, the selected papers were evaluated by strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology, which is a standard, internationally used checklist for paper quality evaluation. This checklist included 43 different parts and methodological aspects of the study such as sampling procedures, variable measurement, and statistical analysis were evaluated.

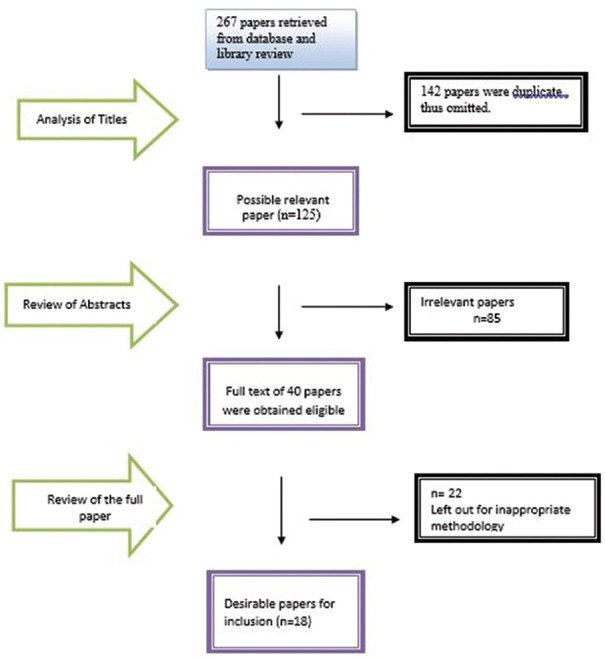

Flowchart

Based on the description provided in the first phase, 267 articles related to incidence, prevalence, epidemiology, and risk factors of MI in Iran were found. Of these, 142 articles were excluded because they had repetitious or irrelevant titles. Abstracts of the remaining 125 articles were examined and 85 articles were excluded due to nonrelevance. In the third stage, the full texts of the remaining 40 articles were reviewed and 22 out of 40 were left out from the study because of methodological problems. Finally, 18 articles were found eligible for the purposes of the study [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing the study selection for systematic review of studies on acute myocardial infarction in Iran

RESULTS

Distribution of myocardial infarction in terms of age and gender

According to the surveys conducted in Iran, women experience CVDs at an older age than men.[9,12] Furthermore, mean age of women was higher than men.[3,5,6,7,11,13,14,15,16,17,18] In a study conducted over 10 years in Tehran, the mean age of incidence of heart attack in women showed a significantly descending pattern.[19] In two studies performed over 10 years in Babol and Tehran, the difference between mean age of male and female were observed to continue.[7,18] Changes in the mean age of AMI were not significant, in the studies conducted in Babol, Tehran, Urmia, and Yazd during several years.[7,18,20,21]

In the study of Birjand during 2000–2004, there was an increase in the mean age of patients with AMI but it was not statistically significant.[5] In a nationwide study conducted by Ahmadi et al. on 20,750 people using MI registry data in 2012, the mean age of AMI patients was significantly different across different provinces[13,14] such that the lowest mean age belonged to Semnan (59.1 years), Tehran (60.4 years), and Lorestan (60.1 years), and the highest average age was in (64.4) Zanjan Province.[14] The mean age of men did not differ between the provinces, whereas for women, the highest mean age was in Ardebil (68.4 years) which showed a significant difference with Hamadan (62.1 years). The lowest mean age[14] studies in Semnan, Birjand, Babol, Gilan, Urmia, Tehran, Yazd, Kermanshah, Kohgiloyeh, Boirahmad, and Isfahan reported a higher incidence of AMI in men than women.[3,5,7,16,17,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]

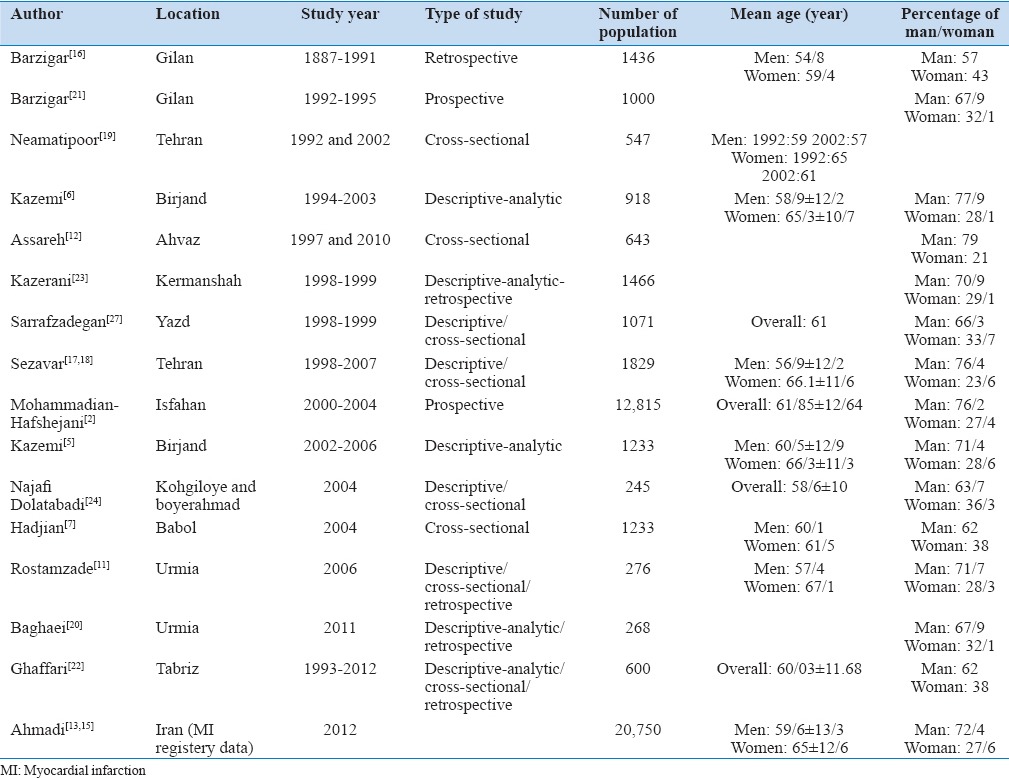

In Iran, there has been a rising trend in the average age of patients with AMI in recent years.[13,14] Table 1 displays age of patients with AMI as reported in different studies conducted in Iran. The mean age of AMI's patients in Iran is different from 58.8 ± 10 years to 62.35 ± 12.64 years.

Table 1.

Iranian studies about myocardial infarction according to location, years, mean age, and sex

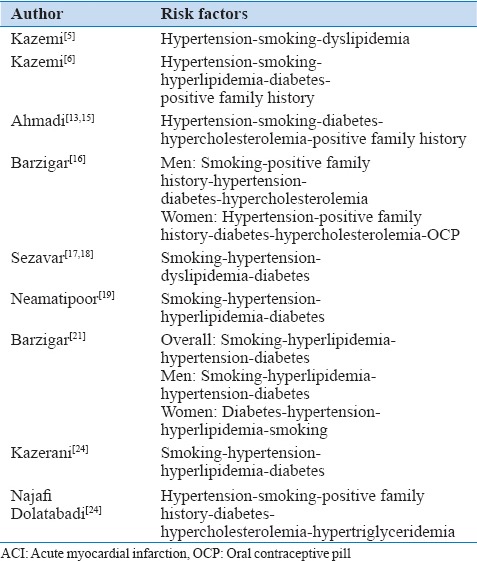

Distribution of risk factors of myocardial infarction

In a study of Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari Province, MI's risk factors included hypertension (HTN), hypercholesterolemia, diabetes mellitus (DM), smoking, stress, and obesity.[9] In Semnan, smoking, HTN, DM, and hypercholesterolemia were the most common risk factors respectively.[3] The same study showed that the risk of AMI in patients with three simultaneous risk factors of DM, HTN, and smoking would be significantly higher.[3] In a series of studies, cardiovascular risk factors were compared in AMI's patients of both genders. In the studies of Urmia and Kermanshah, it was observed that the most common risk factors among men included smoking followed by HTN.[20,23] In Gilan province, the most common risk factors among men were smoking, positive family history of CAD, and HTN, while in women, the most common risk factors were HTN and family history, respectively.[16] Ahmadi et al. observed that the prevalence of DM and HTN was significantly higher in women than men, whereas smoking and family history of CVDs in men overrode those in women.[15] Table 2 shows the major risk factors for MI across the country. Three risk factors for AMI in Iran are HTN, smoking, and dyslipidemia (DLP).

Table 2.

Cardiac risk factors in acute myocardial infarction patients in Iranian studies

Premature myocardial infarction

Studies focused on the populations of Gilan and Isfahan reported AMI admittance percentages of young patients (<40–45 years) as 8.6% and 6.8%, respectively.[16,27] Only in the study conducted over 13 years in Ahvaz, it was observed that the incidence of AMI in patients < 35 years had increased significantly, especially in male patients.[12] According to the study in Kurdistan Province, smoking was a risk factor for premature MI.[28]

Spatial and temporal distribution of myocardial infarction in Iran

In a study by Ahmadi et al., the highest rate of MI incidence in Iran was in January and the lowest in May.[13] The overall incidence of MI across Iran amounted to 73.3/100,000 persons with the highest prevalence in North Khorasan (152.5/100,000) followed by the provinces of Kerman, Khuzestan, Yazd, Semnan, and West Azerbaijan (149.2, 143.7, 141.3, 132.5, and 130.8/100,000, respectively). The lowest rate belonged to Qom Province (24.5 per 100,000).[14] Incidence of AMI overrides national average in more than half of the provinces.[14] Studies conducted in Birjand, Gilan, Urmia, and Isfahan observed that people in urban areas are more likely to undergo AMI than rural people.[5,16,20,27]

In-hospital mortality rate

Studies conducted in Birjand, Urmia, Kermanshah, Yazd in 2006 and 2009 reported that in-hospital mortality rates were 11.5%, 9.1%, 7.1% and 7.5%, respectively.[5,20,23,26] In addition, in-hospital mortality and death 1 month following AMI were significantly higher among women in Urmia and Birjand.[22,29]

DISCUSSION

Due to importance of CVDs, especially AMI, this review looked at MI's epidemiology in Iran. We reported a systematic review on Persian and English literature about the prevalence of AMI, sex differences, age, risk factors, and trend of changes in Iranian AMI patients.

Mean age of myocardial infarction

Mean age of AMI's patients in Iran is different from 58.8 ± 10 years to 62.35 ± 12.64 years; it is lower in male than female. Mean age of patients with AMI in our country is about 10 years lower than in the developed countries.[30] Mean age of AMI patients in Taiwan were 61.14 and 75.13 years (1999–2000 and 2007–2008, respectively), in Sub-Saharan Africa were 56.5 and 63.9 years (2000 and 2012) in the Massachusetts region was 67.13 years in 1999 and 69.14 in 2008.[31,32,33] In Switzerland, in 1998, it was 66.5 ± 13.9 and in 2008, 67.6 ± 13.8 years.[34] In Oman, the average age was 60 years for men and 61 years for women.[35]

Sex differences in acute myocardial infarction

In Iran, male-to-female ratio (M/F) was different from 47/43 to 79/21, 70/30. M/F ratio of AMI in Japan was 70/30, 67/33 in Korea.[36,37] The incidence ratios in various states in the United States in 2007 range from 53% to 73% in men and from 15% to 38% in women.[38] In Taiwan, the M/F ratio is 65.5/34.5, in Switzerland 70/30, and in Oman 56/44.[31,34,35] Therefore, according to the reviewed papers, AMI in Iran has higher incidence in men than women similar to the rest of the world.

Distribution of myocardial infarction risk factors

Literature review showed a higher prevalence of HTN, DM, and smoking in patients with AMI in Iran. In Oman, HTN, DM, and hyperlipidemia had a higher prevalence, whereas smoking had lower prevalence. Furthermore, 30%–60% of patients with AMI and unstable angina in Oman suffered from overweight and obesity.[35]

In Iran, changes in the frequency of risk factors did not show a specific pattern during 1992-2004.[17,18] In details, the prevalence of HTN, DLP, DM, positive family history for CAD, and smoking were on the rise during 1991–2001.[6] In another study during 2000–2004, the percentage of patients with risk factors for HTN and DM were increased.[5] These findings are in agreement with studies in Massachusetts, USA and Oman.[33,35] In Massachusetts, risk factors for HTN, DM, and DLP have become more prevalent from 2000 to 2008, whereas smoking and low-density lipoprotein levels have decreased.[33]

By damaging vascular function, DM paves the way for the development of atherosclerosis and doubles the risk of AMI.[39] It seems that daily consumption and number of cigarette packs per year are associated with progression of impaired fasting glucose and type 2 diabetes as well as metabolic syndrome.[40] A decreased incidence of hospitalization for AMI is associated with smoking ban.[40] Smoking for 25 years or more is associated with increased mortality of CAD.[41] This suggests the importance of interventions for controlling cardiovascular risk factors such as smoking to prevent AMI.

Acute myocardial infarction in young people

Different studies have mentioned the prevalence rate of 5%–15% for MI at an early age in Iran, which has not increased significantly during 1996–2005.[17,18,42] The percentage of early MI in men significantly was more than women.[17,42] In Michigan, 10% of the patients hospitalized for AMI were under 45 years.[43] In the United States, MI in patients under 45 years accounts for 10% of all AMI patients. In addition, MI is more prevalent among men than women.[44]

The most common risk factors for premature MI in Birjand and Tehran were smoking, HTN, and DLP.[1,17] A positive family history of CAD, smoking, and DLP are the major risk factors for AMI among young people in Alizadehasl et al. study.[42] The most common risk factors for premature MI in New York are smoking, positive family history, and HTN. Smoking was of especially high prevalence,[45] in North Carolina alongside other risks such as positive family history, obesity, and HTN. In addition, premature MI was more common among men than women.[46]

In Canada, the relationship between smoking and family history of premature coronary disease in men and women as well as MI has been well demonstraWted.[44] In Michigan, the most common risk factors for premature MI consist of smoking, positive family history, hyperlipidemia, and HTN where smoking and positive family history were more prevalent.[43]

Tobacco smoking has been influenced by historical and cultural backgrounds of the society while in most communities, women smoke less than men. This clearly explains part of the reason why young women had a lower rate of MI than men.[17] As it can be seen, similar to other countries, premature MI in Iran is more prevalent among men than women. Its percentage is similar to other countries, and like them, smoking is the most common risk factor of premature MI, whereas positive family history is also of significant importance.

Trend of changes in myocardial infarction incidence

During the years 1992–2004, an ascending pattern was seen in the percentage of patients with MI in Iran.[5,6] This pattern was in disagreement with developed countries such as Japan, Korea, and US. Furthermore, during 15 years (1991–2004) in-hospital mortality had a descending pattern.[5,6] This is in accordance with a Switzerland study. It can be due to the use of revascularization during two decades in Iran.[6,22,31]AMI's rate of hospitalization was decreased from 1999 to 2008 in Taiwan, Korea (2006 2010), Massachusetts, USA (2000–2008) and Japan (2004–2011).[31,36,37,45] According to this review, the percent of AMI's patients increased in recent years in Iran, but the period of hospitalization and in-hospital death decreased.

Recently, an increase has been observed in the percentage of patients with AMI; this has been attributed to increase in incidence due to increased prevalence of risk factors.[5,6] During the past 30 years, the prevalence of CVD reduced in several developed countries, whereas it seems to have been rising considerably in developing countries.[26] Japan has experienced a steady declining trend in AMI incidence in recent years which may be due to the approval of CVDs' guidelines by Japanese care centers and prescription of lipid decreasing medications that reduce risks of ischemic disease.[36] Incidence of AMI and stroke in Korea has steadily declined between 2006 and 2009. Explanation for this decrease (considered as attempts for the primary and secondary prevention) are thought to be due to the use of efficient drugs and timely cardiovascular interventions - ei, cardiac, and cerebral vessels care projects.[37]

Studies at the national scale in Europe and cross-sectional studies in the United States have indicated reduced AMI admissions upon bans on smoking.[47] In Massachusetts, the incidence of MI is significantly reduced after 2000 due to continued improvements in the primary prevention efforts.[33] Hospitalization for AMI in American men and women has decreased during the years 2000–2008. The decreased rate is observed in New England and Mid-Atlantic regions and states that are near mountains and oceans.[45]

In Taiwan, hospitalization rate has decreased from 1999 to 2008 because of control of hazardous risk factors by the medical systems and education focusing in AMI prevention.[31] AMI incidence is reported from 1.0% to 10% in a few studies carried out in Sub-Saharan Africa where the average has been 4.2%.[32] A high prevalence of acute coronary syndrome has been reported in Oman.[35] In Iran, according to the reviewed papers, the number of AMI patients has been on the rise in recent years, a trend which is similar to those of the developing countries.

In summary, as the WHO has declared, the world must mobilize to overcome non-communicable diseases with focus of AMI. We hoped by reducing the incidence of HTN by 25%, 30% of salt consumption and smoking, 10% of alcohol consumption and inadequate activity, 15% of fat consumption, 20% of hypercholesterolemia, no increase in obesity and diabetes by 2025, we can decrease the rate of premature deaths from heart diseases by 25%. This is named as 25 × 25 target.[48]

CONCLUSION

In Iran, the prevalence of AMI is very high and on the rise. Proper education is required concerning healthy lifestyle, increased physical activity, and healthy dietary choices for all people, especially adolescents and children. In Iran, the prevalence of AMI is higher in men, whereas the mean age of women at the time of incidence is higher. However, female mortality after AMI is higher which is due to their higher age, higher prevalence of diabetes as well as atypical symptoms, and later referrals of women. Therefore, it is required to teach women about the importance of the disease and its clinical manifestations. In Iran, risk factors in AMI, especially in early age consist of smoking, HTN and DLP. Hence, primary prevention and control of these risk factors seem necessary.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

This article is a part of the medical student thesis (Jaber Mohseni) by supervision of Dr. kazemi and Dr. Hosseinzadeh maleki. The authors would like to thank the research deputy of Birjand University of Medical Science due to financial support of this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kazemi T, Sharifzadeh GR, Zarban A, Fesharakinia A, Rezvani MR, Moezy SA, et al. Risk factors for premature myocardial infarction: A matched case-control study. J Res Health Sci. 2011;11:77–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mohammadian-Hafshejani A, Baradaran-Attar Moghaddam H, Sarrafzadegan N, Asadi Lari M, Roohani M, Allah-Bakhsi F, et al. Secular trend changes in mean age of morbidity and mortality from an acute myocardial infarction during a 10-year period of time in Isfahan and Najaf Abad. J Shahrekord Univ Med Sci. 2013;14:101–14. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asgari MR, Alhani F, Anoosheh M. Risk factors in patients with myocardial infraction hospitalized in Fatemieh Hospital in Semnan. Iran J Nurs. 2010;23:8–16. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Firoozabadi MD, Kazemi T. A memorandum of “World heart day 2013” – Stroke mortality among women in Birjand, East of Iran. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2014;19:215. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kazemi T, Sharifzadeh G, Hosseinaii F. Epidemiology of trend of acute myocardial infraction in Birjand between 2002-2006 years. Iran J Epidemiol. 2009;4:35–41. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kazemi T, Sharifzadeh GR. Changes in risk factors, medical care and rate of acute myocardial infarctions in Birjand (1994-2003) ARYA J. 2006;1:271–4. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hadjian K, Jalali F. Age changing patterns of hospitalized patients with acute myocardial infarction in Babol Shahid Beheshti Hospital (1992-2001) J Birjand Univ Med Sci. 2004;11:9–15. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kazemi T, Sharifzadeh G, Zarban A, Fesharakinia A. Comparison of components of metabolic syndrome in premature myocardial infarction in an Iranian population: A case-control study. Int J Prev Med. 2013;4:110–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehralian HA, Salehi S. Myocardial infarction risk factors in the patients referred to Chaharmahal and Bakhtiary province hospitals, 2005. J Shahrekord Univ Med Sci. 2007;9:77–84. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abbasi SH, Kassaian SE, Sadeghian S, Karimi A, Saadat S, Peyvandi F, et al. Introducing the Tehran Heart Center's premature coronary atherosclerosis cohort: THC-PAC study. J Tehran Heart Cent. 2015;10:34–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rostamzade AR, Khademvatan K, Yekta Z, Mohammadzade H. Evaluation of sex effect on mortality in acute myocardial infarction in talegani hospital in Urmia. Urmia Med J. 2006;17:9–15. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Assareh AR, Alasti M. Trend of acute myocardial infarction prevalence toward younger ages in Ahvaz. Iran Heart J. 2011;12:43–7. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmadi A, Soori H, Mehrabi Y, Etemad K, Khaledifar A. Epidemiological pattern of myocardial infarction and modelling risk factors relevant to in-hospital mortality: The first results from the iranian myocardial infarction registry. Kardiol Pol. 2015;73:451–7. doi: 10.5603/KP.a2014.0230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmadi A, Soori H, Mehrabi Y, Etemad K, Samavat T, Khaledifar A, et al. Incidence of acute myocardial infarction in Islamic republic of Iran: A study using national registry data in 2012. East Mediterr Health J. 2015;21:5–12. doi: 10.26719/2015.21.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahmadi A, Soori H, Sajjadi H, Nasri H, Mehrabi Y, Etemad K, et al. Current status of the clinical epidemiology of myocardial infarction in men and women: A national cross-sectional study in Iran. Int J Prev Med. 2015;6:14. doi: 10.4103/2008-7802.151822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barzigar A, Shamkhani K, Manzar HA, Jahangir Bolurchian M, Hemati H, Atrkar Roshan Z, et al. An epidemiological survey on a patient with myocardial infarction in Dr. Heshmat Hospital during 5 years. J Med Fac Guilan Univ Med Sci. 1993;1:8–19. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sezavar SH, Valizadeh M, Moradi Lakeh M, Rahbar MH. Early myocardial infarction and its risk factors in patients admitted in Rasul-e-Akram Hospital. Hormozgan Med J. 2010;14:156–63. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sezavar SH, Valizadeh M, Moradi M, Rahbar MH. Trend of changes in age and gender of patients admitted in Rasul-e-Akram Hospital with first acute myocardial infarction from 1998 to 2007. J Ardabil Univ Med Sci. 2010;10:29–37. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neamatipoor E, Sabri A, Dahi F, Soltanipoor F. Changing risk and demographic factors of myocardial infarction in a decade (1371-1381) in three university hospital. Tehran Univ Med J. 2006;64:88–94. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baghaei R, Parizad N, Alinejad V, Khademvatani K. Epidemiological study of patients with acute myocardial infarction in Seyyed al Shohada Hospital in Urmia. Urmia Med J. 2013;24:763–70. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barzigar A. Evaluation of risk factors associated with systemic disease in 1000 patients of acute myocardial infarction. J Shahid Sadoughi Univ Med Sci Health Serv. 1997;5:28–35. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghaffari S, Hakim H, Pourafkari L, Asl ES, Goldust M. Twenty-year route of prevalence of risk factors, treatment patterns, complications, and mortality rate of acute myocardial infarction in Iran. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;7:117–22. doi: 10.1177/1753944712474093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kazerani H. Epidemiologic study of patients with acute myocardial infarction admitted in Shahid Beheshti Hospital of Kermanshah during 1998-1999. J Ilam Univ Med Sci. 2006;14:40–4. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Najafi Dolatabad SH, Mohebbi Nobandegani Z. Study of myocardial infarction epidemiology at the hospitals of university of medical sciences Kohgiloyeh & boirahmad province 2004, Dena. Q J Yasuj Fac Nurs Midwifery. 2007;2:63–70. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ounpuu S, Negassa A, Yusuf S. INTER-HEART: A global study of risk factors for acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2001;141:711–21. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.114974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sadre Bafghi SM, Shahriari V, Mirbagheri SR, Haghighat S, Halajian M, Namayande SM. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of myocardial infarction. Med J Mashad Univ Med Sci. 2004;46:41–8. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sarrafzadegan N, Oveisgharan S, Toghianifar N, Hosseini S, Rabiei K. Acute myocardial infarction in Isfahan, Iran: Hospitalization and 28th day case-fatality rate. ARYA Atheroscler J. 2009;5:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gheidari ME, Rahimi EA. Risk factors for acute myocardial infarction in young adults of Kurdistan province, Iran. Iran Heart J. 2005;6:44–8. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kazemi T, Sharifzadeh GR. A memorandum of “World Heart Day 2012”: Myocardial infarction mortality in women in Birjand, 2008-2009. J Tehran Heart Cent. 2012;7:191. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saeidi SJ, Bakhshiyian R. Study on 372 military and civillian patients with myocardial infarction hospitalized in 1991 and 2001 years. J Mil Med. 2004;6:117–22. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang HY, Huang JH, Hsu CY, Chen YJ. Gender differences and the trend in the acute myocardial infarction: A 10-year nationwide population-based analysis. Sci World J. 2012;2012:184075. doi: 10.1100/2012/184075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hertz JT, Reardon JM, Rodrigues CG, de Andrade L, Limkakeng AT, Bloomfield GS, et al. Acute myocardial infarction in sub-saharan Africa: The need for data. PLoS One. 2014;9:e96688. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yeh RW, Sidney S, Chandra M, Sorel M, Selby JV, Go AS, et al. Population trends in the incidence and outcomes of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2155–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Insam C, Paccaud F, Marques-Vidal P. Trends in hospital discharges, management and in-hospital mortality from acute myocardial infarction in Switzerland between 1998 and 2008. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:270. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Al-Lawati J, Sulaiman K, Panduranga P. The epidemiology of acute coronary syndrome in Oman: Results from the Oman-RACE study. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2013;13:43–50. doi: 10.12816/0003194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kojima S, Matsui K, Ogawa H. Kumamoto Acute Coronary Events (KACE) Study Group. Temporal trends in hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction between 2004 and 2011 in Kumamoto, Japan. Circ J. 2013;77:2841–3. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-13-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim RB, Kim BG, Kim YM, Seo JW, Lim YS, Kim HS, et al. Trends in the incidence of hospitalized acute myocardial infarction and stroke in Korea, 2006-2010. J Korean Med Sci. 2013;28:16–24. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2013.28.1.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Talbott EO, Rager JR, Brink LL, Benson SM, Bilonick RA, Wu WC, et al. Trends in acute myocardial infarction hospitalization rates for US states in the CDC tracking network. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64457. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moe B, Augestad LB, Flanders WD, Dalen H, Nilsen TI. The adverse association of diabetes with risk of first acute myocardial infarction is modified by physical activity and body mass index: Prospective data from the HUNT study, Norway. Diabetologia. 2015;58:59–66. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3388-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morito N, Miura SI, Yano M, Hitaka Y, Nishikawa H, Saku K, et al. Association between a ban on smoking in a hospital and the in-hospital onset of acute myocardial infarction. Cardiol Res. 2015;6:278–82. doi: 10.14740/cr404e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chang CM, Corey CG, Rostron BL, Apelberg BJ. Systematic review of cigar smoking and all cause and smoking related mortality. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:390. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1617-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alizadehasl A, Sepasi F, Toufan M. Risk factors, clinical manifestation and outcome of acut myicardial infarction in young patient. J Cardiovasc Thorac Res. 2010;2:29–34. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Doughty M, Mehta R, Bruckman D, Das S, Karavite D, Tsai T, et al. Acute myocardial infarction in the young – The university of michigan experience. Am Heart J. 2002;143:56–62. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.120300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pasricha A, Batchelor W. When young hearts are broken: Profiles of premature myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2002;143:4–6. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.120301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zimmerman FH, Cameron A, Fisher LD, Ng G. Myocardial infarction in young adults: Angiographic characterization, risk factors and prognosis (Coronary artery surgery study registry) J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26:654–61. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00254-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kanitz MG, Giovannucci SJ, Jones JS, Mott M. Myocardial infarction in young adults: Risk factors and clinical features. J Emerg Med. 1996;14:139–45. doi: 10.1016/0736-4679(95)02089-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barr CD, Diez DM, Wang Y, Dominici F, Samet JM. Comprehensive smoking bans and acute myocardial infarction among medicare enrollees in 387 US counties: 1999-2008. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176:642–8. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Siadat M, Kazemi T, Hajihosseni M. Cardiovascular risk-factors in the Eastern Iranian population: Are we approaching 25×25 target? J Res Health Sci. 2016;16:51–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]