INTRODUCTION

Doctor–patient relationship is the heart of medicine. It provides an important framework for the conduct of patients and physicians. The encounter has been the subject of considerable discussion and analysis throughout the centuries. Concepts covered range from matters of etiquette to profound questions of philosophical and moral conduct such as abortion, euthanasia, and end-of-life issues.

As a profession, medicine has dealt with these moral issues. The physician, because of his/her special status, acts for the good of the patient. The nature of the physician's job requires moral conduct and accountability. Our concepts of ethics have been derived from religions, philosophies, and cultures. The oaths or pledges that we take or swear allegiance to act as guidelines to a moral dilemma. The doctrines in the oaths allow doctors, patients, and families to generate a treatment plan without any conflict.

There are several codes of medical ethics that can be followed. In this article, we shall consider the history and evolution of the different oaths that we as physicians are bound to follow. Many medical schools administer these pledges upon graduation.

INFORMED MEDICAL CONSENT

In modern times, informed consent is central to the practice of medicine. It covers both health care and the law. There are so many issues related to informed consent that are beyond the scope of this article to discuss.

Doctors and lawyers deal with ethical issues and their life fascinates the public so that they are often the subject of movies or TV series. Currently, I am watching on Netflix “The Good Wife,” a title that intrigues me endlessly, but never mind. I am currently in Season 4. The Good Wife–a lawyer–went to work for a law firm after her husband–a public official–was forced to resign because of a sex scandal and was put in jail because of corruption. The wife had to go back to work, in a law firm, after being a homemaker for so many years. The law firm advises and represents clients, either individuals or corporations, about their legal rights. Of the many and varied cases, the firm represented were clients involved in health care. There were doctors acting as expert witnesses or being accused of causing an adverse reaction to a drug, and clients accusing doctors of a crime such as dishonesty or even murder. It was interesting to watch lawyers trying to manipulate or finding loopholes in the law to suit their case.

Today, hospitals and doctors get a patient to sign an informed consent form, especially before a procedure, to protect the hospital and doctors from law suits. Informed consent is so fundamental and important to modern medicine that we should all be familiar with its subtleties. At the heart of informed consent is respect for a person's dignity. It requires that the patient must have adequate reasoning and be in possession of all relevant facts about the proposed treatment.

If a patient is considered unable to give informed consent, another person is generally authorized to give consent on his/her behalf, for example, parents or legal guardians. Serious ethical issues come up if the patient is considered unable to give informed consent. There are also situations where a normal patient is provided insufficient information to form a reasoned decision so that lawyers step in. Examples are cases in clinical trials in medical research but these are usually anticipated and prevented by an ethics committee or institutional review board. In our institution, there is an ethics committee or medical review board who must consent to a research project. This is for the protection of the hospital, physicians, and patients.

WHAT IS INFORMED MEDICAL CONSENT?

Respect for a person's dignity has been indoctrinated in us since medical school. It is inculcated in us. Who can forget anatomy class? The anatomy professor indoctrinates all students to respect the dignity of the dead person–the corpse has to be treated with reverence and deference. The informed consent is the zenith of such dogma.

So, what exactly is it? It is a process of communication between a clinician and a patient that results in the patient's authorization or agreement to undergo a specific medical intervention. The patient signs a document of his/her agreement to the intervention and this is usually a sufficient evidence that serves to document the legal and ethical responsibility of the clinician and also of the patient. Hence, informed consent protects both the clinician and the patient.

There are many sites on the internet giving advice to clinicians on how to improve and obtain good communication with the patient. An important resource is “Interventions to promote informed consent for patients undergoing surgical and other invasive healthcare procedures” by Kinnersley and published in Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013.[1]

The dialog of informed consent is used in both clinical and research settings. This process of informed consent may occur within one encounter or across multiple encounters.[2]

An informed consent has seven features:

Affirming the patient's role in the decision-making process

Describing the clinical issue and suggested treatment

Stating alternatives to the suggested treatment (including the option of no treatment)

Stating risks and benefits of the suggested treatment (and comparing them to the risks and benefits of alternatives)

Stating related uncertainties

Assessing the patient's understanding of the information provided

Eliciting the patient's preference (and thereby consent).[3] Not every detail needs to be discussed, but all details needed for a “reasonable person” to make a decision must be provided.[4] Therefore, all risks of serious complications, even if they occur very rarely, need to be stated. Less serious risks need to be specified if they occur more commonly.[4]

Historical background

Informed consent was first used in court by the late attorney Paul G. Gebhard in a 1957 medical malpractice suit, Salgo v Leland Jr. University Board of Trustees[5] (Stanford University, California, USA). This case involved a patient named Martin Salgo who awoke paralyzed after aortography, having never been informed that such a risk existed. The defense argued that the doctor had been negligent in not warning Salgo that there was a risk of paralysis. The court ruled that “failure to disclose risks and alternatives was cause for legal action on its own.” This case helped to shape the patient–doctor relationship. It enabled patients to participate in their health care. In addition, the court stipulated that “the physician must seek and secure his patient's consent before commencing an operation or other course of treatment.

Respect for the patient's right of self-determination on a particular therapy demands a standard set by law for physicians rather than one which physicians may or may not impose upon themselves.”[6]

It is unthinkable nowadays to perform a medical procedure without a signed consent by the patient. Clinicians are required to inform patients what the procedure is all about as well as explain its potential risks.

It was not always so.

The notion of informed consent is relatively recent. Traditionally, the doctor–patient relationship has always been paternalistic, that is, the physician believes that he/she has the knowledge and expertise to understand the patient's condition and therefore only he/she knows what is good or best for the patient. To achieve a cure, it was widely felt that authority must be coupled with obedience. Traditionally, doctors have been under the impression that the patient does not understand very well his/her disease or his/her physical condition. Thus, it was deemed necessary that physicians make decisions for patients. This has been the old-style thinking in medicine, but this concept has changed with the advent of informed consent. Physicians felt that any disclosure of possible difficulties might erode patient trust. However, physicians are now required to disclose to the patient what the risks and adverse effects of a contemplated procedure or treatment plan.

Do physicians abide by an ethical code?

For thousands of years, the medical profession has regulated its conduct through the Oath of Hippocrates, a body of ethical statements developed primarily for the benefit of the patient. The oath has historically guided physician's professional conduct. As a member of this profession, a physician must recognize responsibility to patients first and foremost, as well as to the society, to other health professionals, and to self.

Physicians are respected for their knowledge and moral standing. New physicians take the Oath of Hippocrates which was adopted by the medical profession as a guide of professional conduct through the centuries. It is still being used today in graduation ceremonies of many medical schools. The oath was written over 2500 years ago. Although the oath bears the name of Hippocrates, there is no evidence that he wrote it. It is claimed that it was written 100 years after his death. No one knows who wrote it.[7]

In 1500, a German medical school (University of Wittenberg) incorporated taking the oath for its graduating medical students. However, it was not until the 1700s, when the document was translated into English that Western medical schools began regularly incorporating the oath in convocations. In 1948, it was adopted by the World Medical Association (WMA) based in Geneva, and in 1964, it was rewritten by Louis Lasagna (the then Dean of the Tufts University School of Medicine in Boston, Massachusetts, USA) and this version was adopted by many medical schools in the USA.[8] Its principles are held sacred by doctors to this day.

In its original form, the oath requires a new physician to swear, by a number of healing Gods, to uphold specific ethical standards. It is generally believed that the famous phrase, “ first do no harm” is contained in the original Hippocratic Oath but it was not, and it is believed that the motto is found elsewhere in Hippocrates' writings which states that “The physician must…have two special objects in view with regard to disease, namely to do good or to do no harm.”[8]

The original pledge (classical version) promised to “abstain from whatever is deleterious and mischievous,” to “give no deadly medicine to any one if asked,” and to “abstain from every voluntary act of mischief and corruption.”[8]

Physicians breathed the oath in their daily life: Treat the sick to the best of one's ability, preserve patient privacy, teach one's knowledge of medicine to the next generation, etc. These are lofty ideals. The oath is committed to doing what was best for the patient and ethically prohibits abortion, euthanasia (“administering poison”), and sexual relation with patients. These prohibitions make it clear that the physician is surrounded with certain moral standards which take precedence over the individual physician's judgment.[9]

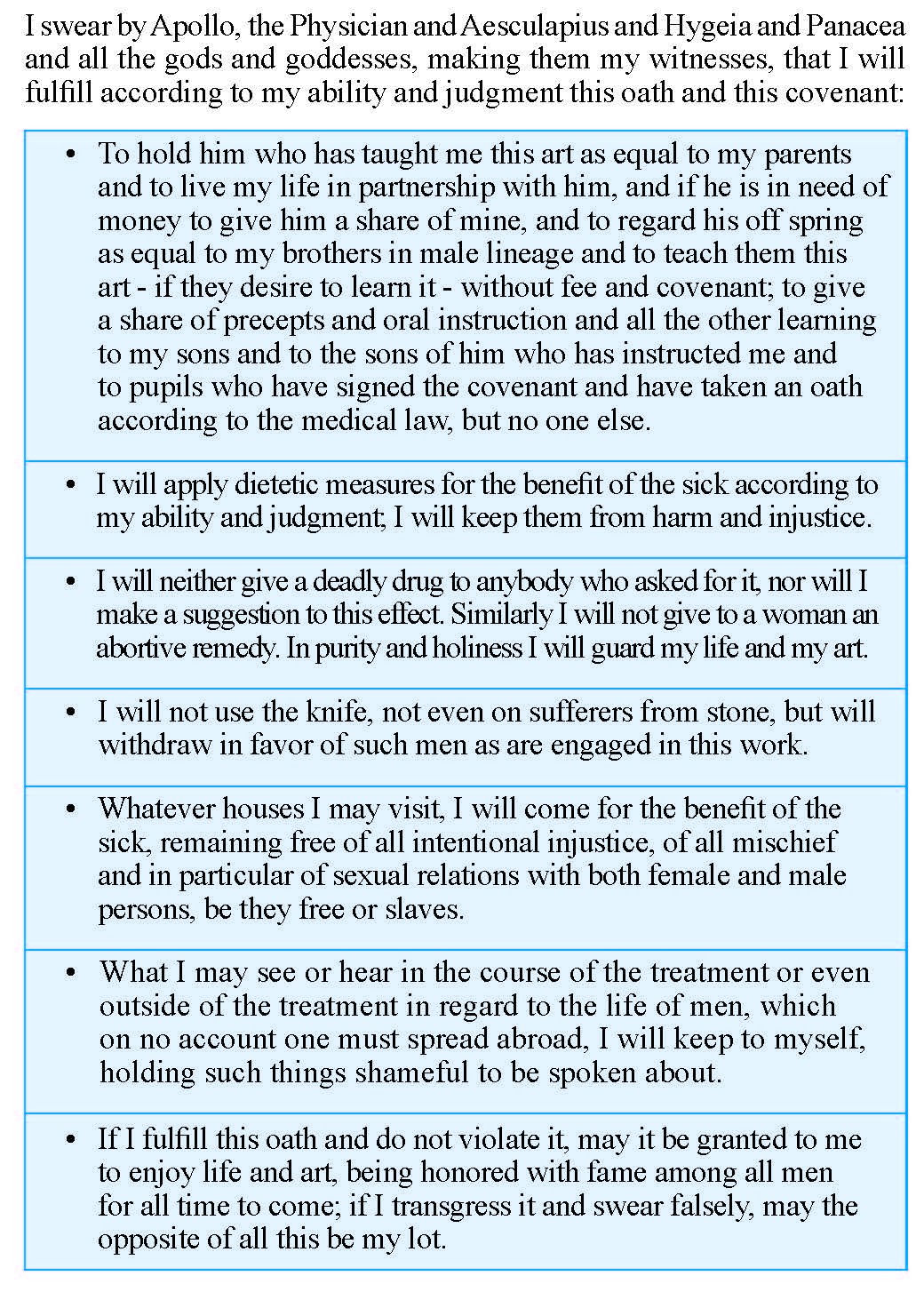

There are two versions of the oath – classical and modern. These are reproduced here for comparison. The classical version of the oath is outdated. Most graduating medical school students swear to a modern version.

Hippocratic oath

The reproduction shown in Table 1[10]and Table 2 is a translation from the Greek by Ludwig Edelstein, from The Hippocratic Oath: Text, Translation, and Interpretation, by Ludwig Edelstein. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1943. It appears in many websites.

Table 1.

The classical version of the Hippocratic Oath

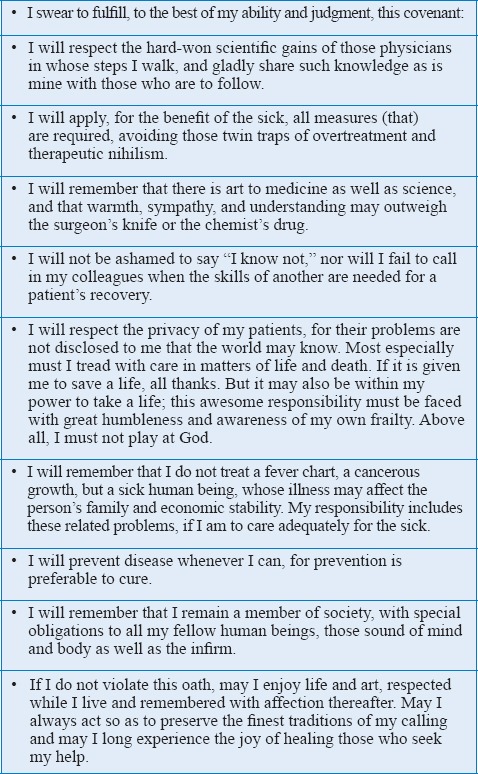

Table 2.

Hippocratic Oath: Modern Version (by Louis Lasagna, Academic Dean of the School of Medicine at Tufts University)

Of note is that, in the modern version of the oath, there is no prohibition against abortion; there is no promise by the physician to “do no harm” or never give a “lethal medicine” as in the original Hippocratic Oath. Undoubtedly, there are many modern ethical issues today that did not exist in the past, such as abortion and euthanasia. The pros and cons of these two topics dominate our world today.

Is the Hippocratic Oath irrelevant today or is it an invaluable moral guide?

Most physicians take the oath upon graduation from medical school. Is the oath still relevant? There are many ethical issues in medicine which cannot be resolved or mediated by signing a consent form alone or swearing to an oath. The ethical landscape has changed. Physicians are faced with a lot of tough ethical issues that never existed in the past.

The oath has generated a lot of controversies, with some claiming that the oath is a meaningless relic of a distant past as it does not address the realities of modern medicine such as abortion, physician-assisted killing (which falls under the broad term euthanasia), and end-of-life issues. It is felt that the oath offers no guidance to the ethical dilemmas in today's medical practice.

Many updated versions of the Hippocratic Oath have been published which use many basic principles of the original, which medical students commonly swear to upon graduation. In some medical schools, the Declaration of Geneva physician's oath is used.[11] In others, an oath individualized by the institution is used.[12] Lasagna's version is the most popular one used by medical schools, with 33% using it and only 11% using the original classical version, according to a 2009 survey of 135 US and Canadian medical schools.[13] A 1993 survey of 150 US and Canadian medical schools claims that only 14% of modern oaths prohibit euthanasia, 8% forbid abortion, and 3% forbid sexual contact with patients. These maxims were held sacred in the classical version.[14]

The Hippocratic Oath covers several important ethical issues between doctors and patients. However, many people believe that the oath does not help resolve modern issues. Some examples are: (1) government and health-care organizations demand more patient information; this makes one wonder how a doctor can maintain a patient's privacy. (2) Are physicians morally obligated to treat patients with lethal new diseases such as AIDS or Ebola virus? With such unanswered issues, many physicians feel that the Hippocratic Oath is inadequate to address the realities of modern medicine.

THE AMERICAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATION

The American Medical Association (AMA), (a professional organization of physicians in the USA to protect the interests of American physicians) adopted the medical ethic concepts embodied in the Hippocratic Oath [Table 3].[9,10]

Table 3.

Principles of medical ethics (American Medical Association)

The AMA states that those mentioned in the table “are not laws but standards of conduct which define the essentials of honorable behavior for physicians.”[9,10]

Today, the Hippocratic Oath “has remained in Western civilization as an expression of ideal conduct for the physician,” and most graduating medical school students swear to some form of the oath, usually a modernized version.[16]

THE WORLD MEDICAL ASSOCIATION (WMA) AND THE DECLARATION OF GENEVA (PHYSICIANS' OATH)

In post-World War II, the WMA in Geneva, Switzerland, was concerned because of revelations that doctors in Nazi Germany conducted wicked and atrocious human experimentation on prisoners of war and civilians of occupied countries; the doctors were also accused of planning and performing the mass murder of prisoners of war and civilians of occupied countries under the guise of euthanasia. There was a Euthanasia Program where the human patients were branded as aged, insane, incurably ill, deformed, and were in nursing homes and asylums. The doctors were reported to have performed medical experiments on such people without the patient's consent. It was proven also that, in the course of such experiments, the defendants committed murders, brutalities, cruelties, tortures, atrocities, and other inhuman acts.[13] The trial is famous in history and known as the Nazi Doctors' Trial at Nuremberg.

Likewise, Japan committed unacceptable human suffering during the Second Sino-Japanese War and World War II. Japan experimented on humans by “field testing” plague bombs and dropping them on Chinese cities to see whether they could start plague outbreaks (which they did!). Unit 731 of the Japanese Imperial Army had a vast research program during and after the World War II. Japan wanted to develop weapons of biological warfare including plague, anthrax, cholera, and a dozen other pathogens. It is estimated that >200,000 Chinese were killed in germ warfare field experiments. The Japanese army doctors carried out medical human experimentation such as vivisection or what they called “practice surgery,” wherein a patient was cut up without anesthesia. These horrible atrocities were committed by some of the Japan's most distinguished doctors.

The US Army granted immunity from war crimes prosecution the Japanese doctors involved in such shameful research practices in exchange for data that were gathered through human experimentation. The information and experience gained in the bio-weapons' research were incorporated into the US biological warfare program. In other words, the US helped cover up human experimentation.[13]

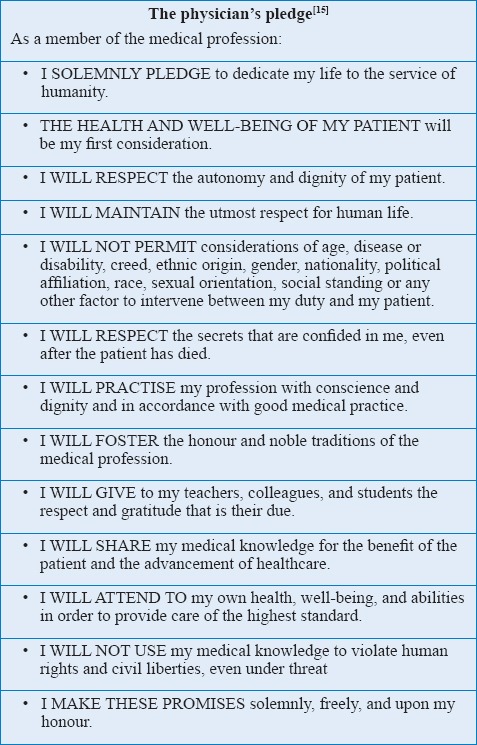

These events and concern over the state of medical ethics in general and all over the world spurred the WMA in Geneva to adopt the Declaration of Geneva[14] or Physician's Oath in 1948, which was amended in 1968, 1983, 1994, and 2017. The Declaration of Geneva [Table 4] was a revision of the Hippocratic Oath, keeping the moral truth of its concepts so that ethical issues of modern medicine are covered. It is a declaration of a physician's dedication to the humanitarian goals of medicine. The WMA took responsibility for setting ethical guidelines for the world physicians and has become the recognized authority to speak for the doctors of the world in international affairs.

Table 4.

The revised 2017 WORLD MEDICAL ASSOCIATION DECLARATION OF GENEVA or Physician's Oath

THE MUSLIM PHYSICIAN AND ETHICS OF MEDICINE

The Muslim physician cannot swear allegiance to the original Hippocratic Oath because of its invocation to various Gods. In Islam, the first source of Islamic law is the Qur'an, which contains the rules of conduct that a person or group hold as reliable in differentiating right from wrong. This is pretty much what ethics is all about – the ability to differentiate between right and wrong. Muslims believe that character traits of the moral and honest physician are already embedded in the Qur'an and the Sunna, the two primary sources of Islamic law. The Sunna is the verbally transmitted record of the teachings, deeds, and sayings of the prophet Muhammad. Therefore, as Muslims grow up, they are guided by the Qur'an and the Sunna, hence the Muslim physician will possess the necessary character traits of a decent and noble physician.

The Qur'an instructs Muslims on all aspects of their daily life, from cleanliness to health matters. The Muslim believer is expected to conduct himself/herself in the best manner possible at all times and places.

A person's character is shaped during childhood and adulthood, and hence character education should begin in childhood – at home and in school. It goes without saying that, if a person is brought up as a virtuous Muslim, he/she will have been taught or trained to be a moral person. The role model for such moral behavior is the prophet Muhammad. Therefore, emulating the prophet Muhammad is desirable for He is an inspiration to everyone. His teachings inspire the lives of people with virtue, good manners, and moderation. Consequently, a good Muslim physician has no need to pledge loyalty to an Oath. Islam sets the foundations for behaving well and possessing the requisite character traits to become a fine person and by extension, a physician with good moral fiber. Muslim physicians are guided by their Quran which clearly states:

“if anyone slays a human being–unless it be [in punishment] for murder or for spreading corruption on earth–it shall be as though he had slain all mankind; whereas, if anyone saves a life, it shall be as though he had saved the lives of all mankind.”[17]

And in another verse:

“Surely Allah enjoins justice, kindness and doing of good, and forbids all that is shameful, evil and oppressive. He exhorts you that you may be mindful.”[18]

CONCLUSION

We know that the heart of medicine is the doctor–patient relationship. Ethics in its unsophisticated form is the ability to differentiate right from wrong. Traditionally, society respects the physician for his/her knowledge and moral standing. The Oath of Hippocrates has historically guided physician's professional conduct. Its principles are held sacred by doctors to this day.

Some say that the oath is irrelevant in modern medical practice because it does not address ethical issues that are relevant today. It is still an invaluable moral guide and has been adopted by the AMA and WMA. Many medical schools still administer a version of the Hippocratic Oath to its graduates.

Muslim physicians are brought up by similar ethical teachings in the Qur'an. A physician with a Western upbringing may or may not swear allegiance to the Oath.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kinnersley P, Phillips K, Savage K, Kelly MJ, Farrell E, Morgan B, et al. Interventions to promote informed consent for patients undergoing surgical and other invasive healthcare procedures. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;7:CD009445. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009445.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edwards WS, Yahne C, Thomas G. Orr Memorial Lecture. Surgical informed consent: What it is and is not. Surgical informed consent: What it is and is not. 1987;154:574–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(87)90219-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braddock CH, 3rd, Fihn SD, Levinson W, Jonsen AR, Pearlman RA. How doctors and patients discuss routine clinical decisions. Informed decision making in the outpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:339–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00057.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lidz CW, Appelbaum PS, Meisel A. Two models of implementing informed consent. Arch Intern Med. 1988;148:1385–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pace E, Gebhard PG. Developer of the Term 'Informed Consent' – New York Times. New York: NYTC; 1997. Aug 26, [Last accessed on 2017 Oct 08]. ISSN 0362-4331. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green DS, MacKenzie CR. Nuances of informed consent: The paradigm of regional anesthesia. HSS J. 2007;3:115–8. doi: 10.1007/s11420-006-9035-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. [Last accessed on 2017 Nov 15]. Available from: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/doctors/oath_doctors.html .

- 8. [Last accessed on 2017 Nov 15]. Available from: https://www.onlinenursing.neu.edu/blog/thehistory-of-the-hippocratic-oath/

- 9. [Last accessed on 2017 Nov 15]. Available from: https://www.bioethics.georgetown.edu/2015/07/physicians-the-morality-of-euthanasia-and-the-hippocratic-oath/was8 .

- 10.Miles SH. The Hippocratic Oath and the Ethics of Medicine. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Last accessed on 2017 Nov 15]. Available from: https://bioethics.georgetown.edu/2015/07/physicians-the-morality-ofeuthanasia-and-the-hippocratic-oath/ [Google Scholar]

- 11. [Last accessed on 2017 Nov15]. Available from: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/body/hippocraticoath-today.html.was10 .

- 12. [Last accessed on 2017 Nov15]. Available from: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wmadeclaration-of-geneva/

- 13. [Last accessed on 2017 Nov15]. Available from: http://www.nytimes.com/1995/03/17/world/unmasking-horror-a-special-report-japan-confronting-gruesomewar-atrocity.html?pagewanted=all .

- 14. [Last accessed on 2017 Nov16]. Available from: http://www.wma.net/en/60about/70history/index.html .

- 15. [Last accessed on 2017 Nov16]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Declaration_of_Geneva#References .

- 16. [Last accessed on 2017 Nov15]. Available from: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/body/hippocraticoath-today.html.was11 .

- 17.Quran Aya: 32. Sura: Almaaida; [Google Scholar]

- 18.The Glorious Quran. Ch. 16, Ver. 90.