Introduction

Suicide and medical assistance in dying are complex phenomena. Suicide is “death caused by self-directed injurious behavior with an intent to die as a result of the behavior.”1 Medical assistance in dying, as per recent Canadian legislation with Bill C-14, which received Royal Assent on June 17, 2016, includes assisted dying from health care professionals for patients who are dying (i.e., “nearing a natural death, without requiring a specific life expectancy”).2,3 Physicians and nurse practitioners, as well as those who help them, including pharmacists, can provide assistance to die to eligible patients.4

Currently, there are more data available for deaths due to suicide than deaths with medical assistance in dying (although these data are imperfect due to reporting issues). Suicide is a major cause of death,5-7 accounting for the deaths of an estimated 800,000 people globally.7 Suicide attempts have been estimated to be 10 to 40 times more frequent than death by suicide and create additional costs to society.8 Up to 90% of suicides are attributed to depression and other mental health disorders.9 Nearly all age groups are affected by suicide, but men aged 40 to 59 years have the highest rates, followed by men aged 60 and older. Adults over 65 years treated for multiple illnesses, including physical and/or mental health conditions, are at higher risk for suicide versus healthy adults of the same age.10-12 The implications of medical assistance in dying legislation on suicide rates are unknown, and statistics will accumulate as appropriate mechanisms are put in place to capture this kind of death.13

Community pharmacists will invariably interact with patients at risk of suicide and those requesting medical assistance in dying, given our roles as stewards of the medication supply and medication therapy experts in primary health care. Individuals who die by suicide have likely had contact with health services in the year prior to their death, including pharmacists, through accessing interventions such as medications.14-16 Self-poisoning with prescription and nonprescription medications is a common method used in suicide and suicide attempts.17 Women die by suicide from self-poisoning in 42% of cases, while men choose this method in 20% of suicide deaths.12 In medical assistance in dying, pharmacists will be involved in the dispensing of medications or directing prescribers and patients to pharmacists offering this service, but the number of Canadian pharmacists who have participated and will participate in this process is currently unknown and will expand with time. Pharmacists will also interact with those who are deemed ineligible for medical assistance in dying but are at risk for suicide.

This distinction, of willful ending of life achieved without supportive actions by health providers (i.e., suicide) versus the same end achieved through health care provider planning and participation (i.e., medical assistance in dying), has profound implications on patients and families, health care providers, health and legal systems, and societal perceptions, attitudes and response. Today, there is much wider acceptance of ending one’s own life, promulgated over recent decades by the right-to-die movement and increasing skepticism of physician authority, but determining the circumstances that are acceptable versus unacceptable is an ongoing challenge.18 In palliative circumstances, distinguishing a request for assisted dying from suicidal ideation or from a more passive wish to die can be subtle, and responses are likely shaped by health care provider experiences and, in some cases, ideology.19,20 In nonpalliative settings, health care provider attitude toward the wish to die of a patient who may be experiencing extreme distress and misery due to severe symptoms and multiple treatment failures, especially when related to mental illness and addictions, can range from one end of the spectrum (empathetic and supportive) to the other (hyperbolic and dismissive).21,22 Regulations in Canada identify a narrow segment of the population (i.e., when the patient’s natural death is reasonably foreseeable, among other criteria) as eligible for medical assistance in dying, intentionally excluding almost all people at risk of suicide where the clinical circumstances are not identified as palliative. Recognition of the unavailability of medical assistance in dying to those living with unresponsive, severe distress and misery may affect health provider attitude, and possibly undeclared actions, toward end-of-life intentions under specific circumstances.

Overall, there is limited published information available regarding pharmacists’ roles and interventions (e.g., education) in the assessment and management of suicide risk or medical assistance in dying. We recently conducted a scoping review regarding pharmacists’ roles and interventions for suicide risk assessment and mitigation and found few studies, most of which used survey methods to assess knowledge and attitudes of pharmacists before and/or following an educational intervention.23 Literature around suicide and medical assistance in dying also has a significant focus on liability and ethical issues.

In 2015, the Canadian Pharmacists Association conducted a survey of members regarding medical assistance in dying, in which 71% of the 978 respondents were community pharmacists.24 Approximately 70% disagreed that pharmacists should be obligated to participate in assisted dying. Sixty-six percent agreed that if a pharmacist does not wish to participate in any aspect of assisted dying, he or she must refer the patient and/or physician to another pharmacist who will fulfill the request. Over 25% of pharmacists disagreed that a federal legislative framework for assisted dying should require pharmacist counselling as part of dispensing lethal medications to physicians, patients or family members.24

Based on the limited data available on this topic, we developed and deployed a survey to Canadian and Australian pharmacists to determine their attitudes regarding suicide. Canada and Australia were chosen, given our recently established research collaborations between 2 countries with similar geographic challenges, health systems and roles for pharmacists.25 Given the recent legislative changes in Canada, we are reporting a preliminary analysis of Canadian pharmacist responses regarding questions about medical assistance in dying.

Methods

The online survey to Canadian pharmacists was available from June 2016 to May 2017. Data for this report were collected on October 7, 2016. The survey consisted of 4 sections, including demographics, the Attitudes Toward Suicide (ATTS) scale,26 the Stigma of Suicide Scale (SOSS)27 and professional experiences with people at risk of suicide. When necessary, questions from the original English translations from the Swedish version of the ATTS were modified for clarity.26

SPSS Statistics version 23 (SPSS, Inc., an IBM Company, Chicago, IL) was used to calculate descriptive statistics for respondent characteristics, independent 2-sided t tests for comparing means and chi-square statistics for categorical comparisons. We grouped 11 items related to permissiveness in attitude towards suicide from the ATTS and calculated total scores per respondent. Mean total scores were compared between groups defined by responses to the 3 survey questions related to closeness to mental illness: personal diagnosis of mental illness, a relative or friend living with mental illness and a person close to them who attempted or died by suicide. Pairwise comparisons were completed for categorical responses (Likert) among the 11 ATTS items based on the above 3 questions.

Ethics approval for the study was received from the research ethics boards of Dalhousie University, Canada, and the University of Sydney, Australia.

Results

Of the 339 surveys that were started, 149 current or former community pharmacists in Canada completed the online survey. The mean (SD) age of respondents was 43 (12) years, with the mean (SD) hours worked per week being 31 (14). Seventy-three percent were female, and participants were located in Atlantic Canada (34%, n = 50), Ontario (28%, n = 41), the Prairies (23%, n = 34), British Columbia (15%, n = 22) and the 3 territories (<1%). Respondents reported their location as rural (27%, n = 41), urban (71%, n = 106) and just over 1% as remote. Eighty-one percent (n = 121) reported currently working as a community pharmacist.

Most pharmacists reported interacting with people at risk of suicide 1 to 2 times (42%, n = 62) and 3 to 5 times (22%, n = 33) throughout their practice experience. Similar proportions indicated experiences of directly interacting with patients at risk of suicide as zero (15%, n = 22), 6 to 10 (11%, n = 16) and more than 10 patients (11%, n = 16).

Permissiveness

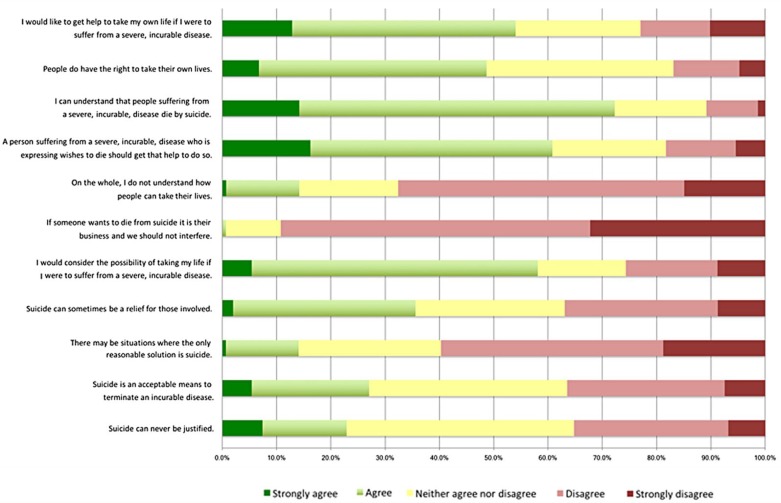

Fifty-eight percent (n = 86) of pharmacist respondents agreed that they would consider taking their own life or getting help to end their life if suffering from a severe, incurable disease, and 72% (n = 107) indicated that they can understand people in this situation choosing to die by suicide (Figure 1). Twenty-seven percent (n = 40) agreed that suicide is an acceptable means of terminating an incurable disease.

Figure 1.

Pharmacists’ permissiveness* towards death by suicide

*Questions for permissiveness were adapted and grouped from the Attitudes Toward Suicide scale.26

There was no association related to closeness to mental illness items (3 items in which people either identified experiencing a mental illness or having a close relationship with someone with a serious mental illness or who died from suicide) and permissiveness (Table 1). When examining responses to the 11 individual items from the ATTS based on these same 3 items, only 2 of 33 pairwise comparisons were identified as p < 0.05 (data not shown). These data do not demonstrate an association between closeness to mental illness or suicidality and the permissiveness of pharmacists’ attitudes towards suicide.

Table 1.

Permissiveness towards suicide and closeness to mental illness

| Three items for closeness to mental illness and suicide | 11-item (ATTS),26 mean total permissiveness score* (n, SD) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| Have you ever been diagnosed with a mental illness (e.g., mood disorder, anxiety disorder, substance use disorder, etc.)? | 35.2 (49, 6.1) | 33.0 (98, 6.6) | 0.76 |

| Does someone close to you (e.g., close friend or relative) live with a mental illness? | 33.9 (114, 6.5) | 33.2 (33, 6.6) | 0.93 |

| Has anyone close to you (e.g., close friend or relative) attempted suicide or died from suicide? | 34.4 (62, 5.9) | 33.3 (85, 6.9) | 0.24 |

ATTS, Attitudes Toward Suicide scale.26

Scoring: 1, strongly disagree; 2, disagree; 3, neither agree nor disagree; 4, agree; 5, strongly agree. Reverse coding was performed on 2 items (Suicide can never be justified; On the whole, I do not understand how people can take their lives).

Discussion

Roles for pharmacists in suicide and medical assistance in dying are emerging and evolving as knowledge and understanding build around suicide and with recent changes in medical assistance in dying legislation. Our preliminary survey analysis indicates that pharmacists perceive a low frequency of direct interaction with those at risk of suicide. Pharmacists may be underestimating those who are at risk for suicide and those who may seek medical assistance in dying in their care, given their likelihood of interacting with numerous groups of people known to have higher risk than the general population for suicide attempts, suicide and a desire to hasten death (e.g., those with serious mental illness, those with multimorbidity aged 65 years, those with terminal diagnoses, etc.). Death by suicide occurs in approximately 1 in 10,000 (age-standardized) Canadians.28 Given that attempts are 10 to 40 times more frequent, up to 40 per 10,000 Canadians attempt suicide, and more experience suicidal ideation than attempt suicide.

This preliminary finding has implications for education and training of pharmacists and the need for more research to explore what pharmacists require in individual practice settings and within the health system to support their care of those at risk of suicide as well as those seeking medical assistance in dying. Advances have been made in some pharmacy undergraduate programs with the incorporation of mental health first aid into curricula and the use of first voice from patients in the classroom setting to improve mental health literacy and skills in managing those presenting with wishes to die.29-31 Other programs have been implemented for practising pharmacists around depression and screening.32-35

While pharmacists may be empathetic towards those who wish to die by suicide, there appears to be some resistance to endorsing this form of death. Over 70% indicated that they can understand that people with an incurable disease choose to die by suicide, whereas 14% agreed that there can be situations in which the only reasonable option is suicide. This finding is in keeping with those from the Canadian Pharmacists Association survey, in which 70% of responding pharmacists disagreed that pharmacists should be obligated to participate in assisted dying.24 A significant implication is that pharmacists themselves may present barriers to patients who seek medical assistance in dying. Interventions may be required to address the cognitive dissonance that exists with pharmacists’ perceptions of people considering medical assistance in dying versus their willingness to engage in the process of medical assistance in dying. Further work will also be required to determine if attitudes are altered depending on whether the incurable illnesses are mental or physical in origin.

Limitations

The survey is ongoing, and the results in this preliminary analysis are of 149 Canadian respondents. As with most surveys, this cross-sectional data collection represents responses that are based on self-administered reporting with no direct observation of behaviours in practice or further opportunity for respondent explication for their responses to these questions.

Our grouping of 11 ATTS survey questions for permissiveness was done based on our knowledge of the literature and clinical experience in this area. We did not conduct a factor analysis for various constructs, as others have reported when using the ATTS.26,36 Although not exactly the same, our question grouping is similar to these other reports.

Our survey questions did not include a definition as to whether incurable diseases are mental, physical or both in their etiology, which may change participant responses.

Framing effects (e.g., wording and context effects) of this questionnaire may have influenced the responses of participants, thus demanding caution around the interpretation of results.37 This is especially important in the field of bioethics and on topics such as suicide and medical assistance in dying. For example, the ATTS specifically refers to “suicide,” without directly using the term medical assistance in dying. This is a wording effect and may have influenced pharmacists to have less permissive attitudes given the pervasive stigma associated with suicide. For question order effect, which is a type of context effect, the order of ATTS questions may have created variability in responses. In other literature, question order effect manifests when preceding questions create thoughts and feelings such that they carry over to subsequent questions. Research regarding surveys in medical assistance in dying shows that framing effects can create large variations in responses.37 Consideration of framing effects in the current body of evidence for pharmacists on this topic is limited and should be bolstered for future survey development and deployment.

Conclusion

Pharmacists are likely underestimating their frequency of interactions with people with thoughts of dying or with intentions to die either by suicide or through medical assistance in dying procedures. Pharmacists report empathetic responses for those with severe and incurable diseases wishing to end their life, but most do not support death by suicide or through medical assistance. From the preliminary analysis, a personal connection to mental illness or suicide does not appear to influence the permissiveness of pharmacists’ attitudes towards suicide. Framing effects in survey research for pharmacists have not been adequately considered, and more work is needed to determine how this influences the responses of pharmacists.

Acknowledgments

Drs. Fred Burge, Stan Kutcher, Timothy F. Chen, Alan Rosen, Luis Salvador-Carulla, Ms. Stephanie Webster, and Ms. Dani Himmelman are members of the research team who all contributed to the design and development of the funded study.

Footnotes

Author Contributions:A. L. Murphy, C. O’Reilly, R. Martin-Misener and D. M. Gardner contributed to the study design and protocol, funding application, acquisition of results, analysis of results and interpretation of findings. R. Ataya provided feedback on the survey design, participated in data acquisition through survey deployment and monitoring, and took part in data analysis and interpretation. A. L. Murphy drafted the initial manuscript. All authors provided critical comment and review and approve the final version.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests:The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding:The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by the Dalhousie Pharmacy Endowment Fund (DPEF). R. Ataya received funding as a research trainee through the DPEF grant. Funding from the Pharmacy Council of New South Wales supported the Australian component of the study. The initial meetings for A. L. Murphy and D. M. Gardner to collaborate with Australian colleagues to prepare the DPEF grant proposal were supported by funding from the Drug Evaluation Alliance of Nova Scotia through sabbatical support for A. L. Murphy and D. M. Gardner.

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Injury prevention and control: division of violence prevention. Available: www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/suicide/definitions.html (accessed Oct. 16, 2016).

- 2. Department of Justice. Questions and answers. Available: http://justice.gc.ca/eng/cj-jp/ad-am/faq.html (accessed Oct. 16, 2016).

- 3. Government of Canada. Medical assistance in dying. Available: www.healthycanadians.gc.ca/health-system-systeme-sante/services/end-life-care-soins-fin-vie/medical-assistance-dying-aide-medicale-mourir-eng.php (accessed Oct. 16, 2016).

- 4. Parliament of Canada. Bill C-14 (Royal Assent). June 17, 2016. Available: www.parl.gc.ca/HousePublications/Publication.aspx?DocId=8384014. (accessed Oct. 16, 2016).

- 5. Brickell TA, Nichols TL, Procyshyn RM, et al. Patient safety in mental health. Edmonton, Alberta: Canadian Patient Safety Institute and Ontario Hospital Association; 2009;58. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hegerl U, Wittenburg L, Arensman E, et al. Optimizing suicide prevention programs and their implementation in Europe (OSPI Europe): an evidence-based multi-level approach. BMC Public Health 2009;9:428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. World Health Organization. Suicide data. 2016. Available: www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicide/suicideprevent/en/ (accessed Oct. 16, 2016).

- 8. Bertolote JM, Fleischmann A, De Leo D, et al. Suicide attempts, plans, and ideation in culturally diverse sites: the WHO SUPRE-MISS community survey. Psychol Med 2005;35(10):1457-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. The Conference Board of Canada. Mortality due to mental disorders. Available: www.conferenceboard.ca/hcp/details/health/mortality-mental-disorders.aspx (accessed Oct. 16, 2016).

- 10. Public Health Agency of Canada. The Chief Public Health Officer’s report on the state of public health in Canada 2010. Available: www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/cphorsphc-respcacsp/2010/fr-rc/cphorsphc-respcacsp-06-eng.php (accessed Oct. 16, 2016).

- 11. Juurlink DN, Herrmann N, Szalai JP, et al. Medical illness and the risk of suicide in the elderly. Arch Intern Med 2004;164(11):1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Navaneelan T. Suicide rates: an overview. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Canadian Medical Protective Association. Completing medical certificates of death: who’s responsible? 2016. Available: https://www.cmpa-acpm.ca/-/completing-medical-certificates-of-death-who-s-responsible- (accessed Oct. 16, 2016).

- 14. Ahmedani BK, Simon GE, Stewart C, et al. Health care contacts in the year before suicide death. J Gen Intern Med 2014;29(6):870-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Smith EG, Kim HM, Ganoczy D, et al. Suicide risk assessment received prior to suicide death by Veterans Health Administration patients with a history of depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2013;74(3):226-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vannoy SD, Robins LS. Suicide-related discussions with depressed primary care patients in the USA: gender and quality gaps: a mixed methods analysis. BMJ Open 2011;1(2):e000198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Finkelstein Y, Macdonald EM, Hollands S, et al. Risk of suicide following deliberate self-poisoning. JAMA Psychiatry 2015;72(6):570-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Purvis TE. Debating death: religion, politics, and the Oregon Death With Dignity Act. Yale J Biol Med 2012;85(2):271-84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ohnsorge K, Gudat H, Rehmann-Sutter C. Intentions in wishes to die: analysis and a typology—a report of 30 qualitative case studies of terminally ill cancer patients in palliative care. Psychooncology 2014;23(9):1021-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Guirimand F, Dubois E, Laporte L, et al. Death wishes and explicit requests for euthanasia in a palliative care hospital: an analysis of patients’ files. BMC Palliat Care 2014;13(1):53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hirsch J. The wish to die: assisted suicide and mental illness. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care 2016;12(3):231-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Downie J, Chambaere K, Bernheim JL. Pereira’s attack on legalizing euthanasia or assisted suicide: smoke and mirrors. Curr Oncol 2012;19(3):133-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Murphy AL, Hillier K, Ataya R, et al. A scoping review of community pharmacists and patients at risk of suicide. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2017;150:366-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Canadian Pharmacists Association. Submission to the External Panel on Options for a Legislative Response to Carter v. Canada. Available: https://www.pharmacists.ca/cpha-ca/assets/File/cpha-on-the-issues/CPhA%20Submission%20to%20the%20External%20Panel%20on%20Legislative%20Options%20for%20Assisted%20Dying.pdf (accessed Oct. 16, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 25. Murphy AL, Gardner DM, Chen TF, et al. Community pharmacists and the assessment and management of suicide risk. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2015;148:171-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Renberg ES, Jacobsson L. Development of a questionnaire on Attitudes Towards Suicide (ATTS) and its application in a Swedish population. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2003;33(1):52-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Batterham PJ, Calear AL, Christensen H. The Stigma of Suicide Scale: psychometric properties and correlates of the stigma of suicide. Crisis 2013;34(1):13-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. The Conference Board of Canada. Suicides: provincial and territorial trends. 2016. Available: www.conferenceboard.ca/hcp/provincial/health/suicide.aspx (accessed Oct. 16, 2016).

- 29. O’Reilly CL, Bell JS, Kelly PJ, et al. Impact of mental health first aid training on pharmacy students’ knowledge, attitudes and self-reported behaviour: a controlled trial. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 2011;45(7):549-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Patten SB, Remillard A, Phillips L, et al. Effectiveness of contact-based education for reducing mental illness-related stigma in pharmacy students. BMC Med Educ 2012;12:120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. O’Reilly CL, Bell JS, Chen TF. Consumer-led mental health education for pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ 2010;74(9):167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Borja-Hart N, Wooten A, Debile T. Screening and management of depression in patients with chronic disease. J Pharm Pract 2012;25(2):272. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rosser S. Development, implementation, and evaluation of a pharmacist-conducted screening and educational intervention for depression. J Am Pharm Assoc 2010;50(2):225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hare SK, Kraenow K. Depression screenings: developing a model for use in a community pharmacy. J Am Pharm Assoc 2008;48(1):46-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. O’Reilly CL, Wong E, Chen TF. A feasibility study of community pharmacists performing depression screening services. Res Social Adm Pharm 2015;11(3):364-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Norheim AB, Grimholt TK, Loskutova E, et al. Attitudes toward suicidal behaviour among professionals at mental health outpatient clinics in Stavropol, Russia and Oslo, Norway. BMC Psychiatry 2016;16:268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Magelssen M, Supphellen M, Nortvedt P, et al. Attitudes towards assisted dying are influenced by question wording and order: a survey experiment. BMC Med Ethics 2016;17(1):24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]