Abstract

Background and Aims

The Share 35 policy was implemented in June 2013 to improve equity in access to liver transplantation (LT) between patients with fulminant liver failure and those with cirrhosis and severe hepatic decompensation. The aim of this study was to assess post-LT outcomes after Share 35.

Methods

Relevant donor, procurement, and recipient data were extracted from the OPTN/UNOS database. All adult deceased donor LT from January 1, 2010 to March 31, 2016 were included in the analysis. One-year patient survival before and after Share 35 was assessed by multivariable Cox proportional hazards analysis, with adjustment for variables known to affect graft survival.

Results

Of 34,975 adult LT recipients, 16,472 (47.1%) were transplanted after the implementation of Share 35, of whom 4,599 (27.9%) had a Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) ≥35. One-year patient survival improved from 83.9% to 88.4% after Share 35 (p<0.01) for patients with MELD ≥35. There was no significant impact on survival of patients with MELD <35 (p=0.69). Quality of donor organs, as measured by Donor Risk Index without the regional share component, improved for patients with MELD ≥35 (p<0.01) and worsened for patients with lower MELD (p<0.01). In multivariable Cox regression analysis, Share 35 was associated with improved one-year patient survival (hazard ratio 0.69, 95% confidence interval 0.60–0.80) in recipients with MELD ≥35.

Conclusion

Share 35 has had a positive impact on survival after transplantation in patients with MELD ≥35, without a reciprocal detriment in patients with lower acuity. This was in part a result of a more favorable donor-recipient matching.

Keywords: Post-transplant outcomes, organ allocation, regional sharing, donor risk index, liver transplant policy

The number of patients in need of liver transplantation (LT) has been rising in the United States (US) as the burden of chronic liver disease increases, without a commensurate increase in available donors. The resulting shortage of organs has challenged the liver transplant community to implement policies by which scarce resources are allocated in the most efficient and equitable manner. The introduction of the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) in 2002 reflects societal mandate to direct organs to patients at the highest risk of mortality from severe hepatic decompensation.(1, 2) Patients waitlisted with acute fulminant liver failure remain an exception to the system, as their short-term mortality is dramatically higher than patients with chronic liver disease; these candidates are designated as Status 1A.

Another aspect of providing patients in need of transplantation with access to organs is geographic distribution of the donor organs. Currently, the US is divided into 11 geographic regions, composed of 58 donor service areas, which are smaller primary geographical units within which donated organs are preferentially directed to local residents in need of them. Status 1A candidates are again an exception, as the system acknowledges the urgency with which these patients must be transplanted. These patients are able to access organs from the entire region and not just a specific donor service area, which has provided them with higher rates of transplantation and lower waitlist mortality, without an impact on non-Status 1 candidates.(3)

Over time, as the medical acuity of patients with end-stage liver disease awaiting transplantation increases and the donor shortage persists, data have emerged that patients with very high MELD (i.e. greater than 35) may be faced with a mortality risk that is comparable to that of patients listed as Status 1A candidates.(4) The Share 35 policy was implemented in June 2013 to improve equity between these two groups of patients. With Share 35, cirrhotic patients with advanced hepatic decompensation are now given the same geographical access to organs as patients with fulminant liver failure, while the latter group is still granted higher allocation status in a given region.

Evaluations of the impact of the Share 35 policy have been mixed. Clearly, it has provided better access to organs for patients with MELD ≥ 35; however, the magnitude of its impact on waitlist mortality has been debated.(5–8) Critics of broader sharing to address geographic disparity in access to donor organs have cited various results of Share 35 policy to dissuade efforts to change the organ distribution scheme.(6, 9, 10) In this work, we analyze the impact of Share 35 on post-transplant outcomes, in terms of recipient mortality and graft survival, particularly among recipients with MELD ≥ 35 at the time of liver transplantation.

Methods

Patients and Data Acquisition

This is a retrospective cohort study, incorporating all US adult LT recipients represented in the Standard Transplant Analysis and Research (STAR) files from January 1, 2010 to March 31, 2016, available from the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). Relevant donor, procurement, and recipient data were extracted from the OPTN database. All adult primary deceased donor liver transplants were included in the analysis, including multi-organ transplants and exception cases. Living donor liver transplants, those without post-transplant data available, and those listed as Status 1A were excluded.

From the STAR file, a broad array of donor, recipient, and transplant variables were extracted. Patients were stratified into MELD ≥ 35 and MELD < 35 by the allocation MELD score at the time of LT. The donor risk index (DRI), a measure of donor quality, was calculated based on donor variables (age, sex, height, race, cause of death, cold ischemia time, share type, split/partial liver transplantation, and donation after cardiac death [DCD]) as described by Feng et al.(11)

Data Analysis

The primary outcome of this study was one-year post-transplant mortality. The secondary outcome was one-year post-transplant graft survival, as defined by death or re-transplantation. Patients were censored on the day of last follow-up if either death or re-transplantation had not occurred, and all observations were censored after 365 days.

Kaplan Meier survival curves were used to describe unadjusted one-year patient and graft survival. Tests for differences in survival were performed using the log-rank test. Univariate and bivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models were performed to evaluate the association of Share 35 with post-transplant outcomes. The bivariate model considered Share 35 and DRI as predictors of one-year survival. Additional analyses were performed with DRI without the regional share component, as well as waiting list time, added to the model.

Multivariable Cox proportional hazards analysis was performed, with adjustment for donor, procurement, and recipient variables that were significant in univariate analysis. Region, recipient BMI, donor race, donor HCV antibody, and split/partial grafts were also included in the multivariable model, as existing data have shown that these variables may affect patient or graft survival.(10–12) Donor and recipient variables were tested for statistical interaction with the post-Share 35 era. Sensitivity analyses were performed for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), patients undergoing simultaneous liver-kidney transplantation, and patients with MELD 30–34 at LT. To assess for geographic variation, the model was also stratified by region.

Variables were compared among groups using t-tests, chi-square tests, one-way analysis of variance, and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, as appropriate. For all analyses, a p-value of < 0.05 was considered significant, and all tests were 2-tailed. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC).

Results

There were 34,975 deceased donor liver transplants meeting inclusion criteria for the study, 16,472 (47.1%) of which occurred after the implementation of Share 35. This included 8,220 (23.5%) recipients with MELD ≥ 35 at the time of LT, with 4,599 (55.9%) transplants occurring in the post-Share 35 era.

Table 1 describes recipient characteristics, pre- and post-Share 35, by MELD strata. Compared to recipients in the pre-Share 35 era, those in the post-Share 35 era were less likely to have a diagnosis of HCV-related liver disease or a history of prior liver transplantation. Patients with MELD ≥ 35 after Share 35 were more likely to be hospitalized in ICU at time of transplantation. In the post-Share 35 era, 402 (9%) of the 4,599 transplants in the MELD ≥ 35 group were transplanted as exception cases, compared to 232 (6%) of the 3,621 transplants before the policy was implemented. Patients in the MELD ≥ 35 group who were transplanted with exception points received organs of similar quality, as measured by the DRI, compared to those without exception points (p=0.53).

Table 1.

Recipient characteristics for patients pre- and post- Share 35 (2010–2016).BMI = body mass index; HCV = hepatitis C; ICU = intensive care unit; IQR = interquartile range; LT = liver transplantation; SD = standard deviation; SLK = simultaneous liver-kidney transplantation.

| MELD ≥ 35 | MELD < 35 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| PRE-SHARE 35 (n=3,621) | POST-SHARE 35 (n=4,599) | p-value | PRE-SHARE 35 (n=14,882) | POST-SHARE 35 (n=11,873) | p-value | |

|

| ||||||

| Recipient age (years) (IQR) | 55 (48–60) | 55 (47–61) | p=0.19 | 57 (52–62) | 59 (53–63) | p<0.01 |

| Female (%) | 1278 (35) | 1756 (38) | p<0.01 | 4588 (31) | 3593 (30) | p=0.32 |

| Race (%) | ||||||

| White | 2367 (65) | 2932 (64) | p=0.11 | 10726 (72) | 8721 (73) | p=0.08 |

| African American | 370 (10) | 479 (10) | 1484 (10) | 1132 (10) | ||

| Hispanic | 180 (5) | 283 (6) | 858 (6) | 631 (5) | ||

| Other | 704 (19) | 905 (20) | 1814 (12) | 1389 (12) | ||

| Etiology of liver disease (%) | ||||||

| Acute hepatic necrosis | 81 (2) | 106 (2) | p<0.01 | 103 (1) | 82 (1) | p<0.01 |

| Non-cholestatic non-HCV | 1324 (37) | 2026 (44) | 4253 (29) | 3669 (31) | ||

| Hepatitis C virus | 1136 (31) | 1085 (24) | 3803 (26) | 2688 (23) | ||

| Cholestatic liver disease | 350 (10) | 442 (10) | 1125 (8) | 792 (7) | ||

| Metabolic liver disease | 106 (3) | 136 (3) | 355 (2) | 263 (2) | ||

| Primary diagnosis of tumor | 371 (10) | 508 (11) | 4758 (32) | 3984 (34) | ||

| Other | 253 (7) | 296 (6) | 485 (3) | 395 (3) | ||

| Exception case at transplant (%) | 232 (6) | 402 (9) | p<0.01 | 6536 (44) | 5848 (49) | p<0.01 |

| Medical condition at transplant (%) | ||||||

| Hospitalized, in ICU | 1440 (40) | 2014 (44) | p<0.01 | 543 (4) | 352 (3) | p<0.01 |

| Hospitalized, not in ICU | 1708 (47) | 1912 (42) | 2137 (14) | 1479 (13) | ||

| Not hospitalized | 473 (13) | 641 (14) | 12202 (82) | 9987 (85) | ||

| SLK (%) | 509 (14) | 683 (15) | p=0.31 | 941 (6) | 893 (8) | p<0.01 |

| Diabetes (%) | 877 (24) | 1102 (24) | p=0.69 | 3990 (27) | 3508 (30) | p<0.01 |

| Portal vein thrombosis (%) | 433 (12) | 574 (12) | p=0.47 | 1682 (11) | 1470 (12) | p<0.01 |

| Prior liver transplant (%) | 437 (12) | 440 (10) | p<0.01 | 506 (3) | 262 (2) | p<0.01 |

| Previous abdominal surgery (%) | 1714 (47) | 2086 (45) | p=0.07 | 6832 (46) | 5620 (47) | p=0.02 |

| BMI (kg/m2) (± SD) | 28.6 (± 6.1) | 28.8 (± 6.5) | p=0.23 | 28.4 (± 5.6) | 28.4 (± 5.5) | p=0.85 |

| Biochemical MELD score at LT (IQR) | 38 (34–42) | 37 (33–41) | p<0.01 | 18 (12–25) | 17 (11–24) | p<0.01 |

| Days on waitlist (IQR) | 23 (7–159) | 20 (5–174) | p<0.01 | 120 (34–321) | 147 (48–359) | p<0.01 |

Table 2 compares donor characteristics by era and MELD strata. As expected, after the implementation of Share 35, utilization of regionally shared organs increased from 22% to 62% of all transplants for recipients with MELD ≥ 35, and distance from donor hospital to transplant center increased from a median of 53 miles (IQR 9–162) to 154 miles (IQR 43–303) (p<0.01). The proportion of regionally shared organs and distance traveled did not increase significantly for patients with MELD < 35 post-Share 35. Cold ischemia times increased from 6.6 to 6.7 hours (p<0.01) for the MELD ≥ 35 group, but decreased from 6.5 to 6.2 hours (p<0.01) for the MELD < 35 group.

Table 2.

Donor characteristics for patients pre- and post- Share 35 (2010–2016).CVA = cerebrovascular accident; IQR = interquartile range; ALT = alanine aminotransferase; AST = aspartate aminotransferase; SD = standard deviation.

| MELD ≥ 35 | MELD < 35 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| PRE-SHARE 35 (n=3,621) | POST-SHARE 35 (n=4,599) | p-value | PRE-SHARE 35 (n=14,882) | POST-SHARE 35 (n=11,873) | p-value | |

|

| ||||||

| Donor age, years | ||||||

| < 40 | 1865 (52) | 2510 (55) | p=0.02 | 6605 (44) | 5332 (45) | p=0.15 |

| 40–49 | 729 (20) | 890 (19) | 2827 (19) | 2129 (18) | ||

| 50–59 | 695 (19) | 815 (18) | 3033 (20) | 2465 (21) | ||

| 60–69 | 279 (8) | 340 (7) | 1786 (12) | 1405 (12) | ||

| 70+ | 53 (2) | 44 (1) | 631 (4) | 542 (5) | ||

| Donation by cardiac death | 98 (3) | 93 (2) | p=0.04 | 794 (5) | 939 (8) | p<0.01 |

| Split or partial LT | 32 (1) | 33 (1) | p=0.40 | 219 (1) | 155 (1) | p=0.25 |

| Donor ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 2229 (62) | 2850 (62) | p=0.79 | 9877 (66) | 7885 (66) | p=0.66 |

| Black | 565 (16) | 681 (15) | 2819 (19) | 2217 (19) | ||

| Hispanic | 655 (18) | 849 (18) | 1582 (11) | 1255 (11) | ||

| Other | 172 (5) | 219 (5) | 604 (4) | 516 (4) | ||

| Donor cause of death | ||||||

| Anoxia | 888 (25) | 1373 (30) | p<0.01 | 3792 (25) | 4085 (34) | p<0.01 |

| CVA/stroke | 1299 (36) | 1458 (32) | 5736 (39) | 3982 (34) | ||

| Head trauma | 1357 (37) | 1660 (36) | 4966 (33) | 3505 (30) | ||

| Other | 77 (2) | 108 (2) | 388 (3) | 301 (3) | ||

| Cold ischemia time (hours ± SD) | 6.6 (± 2.9) | 6.7 (± 2.6) | p<0.01 | 6.5 (± 2.8) | 6.2 (± 2.6) | p<0.01 |

| Distance (miles) (IQR) | 53 (9–162) | 154 (43–303) | p<0.01 | 52 (6–151) | 54 (6–158) | p=0.10 |

| Donor height (cm ± SD) | 171.4 ± 10.2 | 171.5 ± 10.2 | p=0.88 | 171.3 (± 11.0) | 171.1 (± 11.2) | p=0.13 |

| Share type | ||||||

| Local | 2772 (77) | 1734 (38) | p<0.01 | 11768 (79) | 9153 (77) | p<0.01 |

| Regional | 792 (22) | 2832 (62) | 2547 (17) | 2098 (18) | ||

| National | 57 (2) | 33 (1) | 567 (4) | 622 (5) | ||

| Macrosteatosis 30% (% of biopsied) | 61 (7) | 78 (7) | p=0.96 | 423 (8) | 487 (10) | p<0.01 |

| Donor creatinine (mg/dL) (IQR) | 1.0 (0.7–1.4) | 1.0 (0.8–1.5) | p=0.03 | 1.1 (0.8–1.6) | 1.1 (0.8–1.7) | p<0.01 |

| Donor bilirubin (mg/dL) (IQR) | 0.7 (0.4–1.1) | 0.7 (0.4–1.0) | p=0.29 | 0.7 (0.4–1.1) | 0.7 (0.4–1.0) | p<0.01 |

| Donor ALT (IU/mL) (IQR) | 34 (21–65) | 35 (21–67) | p=0.91 | 35 (21–67) | 37 (21–77) | p<0.01 |

| Donor AST (IU/mL) (IQR) | 42 (26–76) | 41 (24–74) | p=0.06 | 44 (26–83) | 44 (25–86) | p=0.57 |

| Donor risk index (IQR) | 1.35 (1.15–1.63) | 1.39 (1.19–1.66) | p<0.01 | 1.45 (1.19–1.77) | 1.48 (1.20–1.79) | p<0.01 |

| Donor risk index without regional share (IQR) | 1.33 (1.12–1.59) | 1.29 (1.11–1.56) | p<0.01 | 1.43 (1.17–1.74) | 1.46 (1.18–1.75) | p<0.01 |

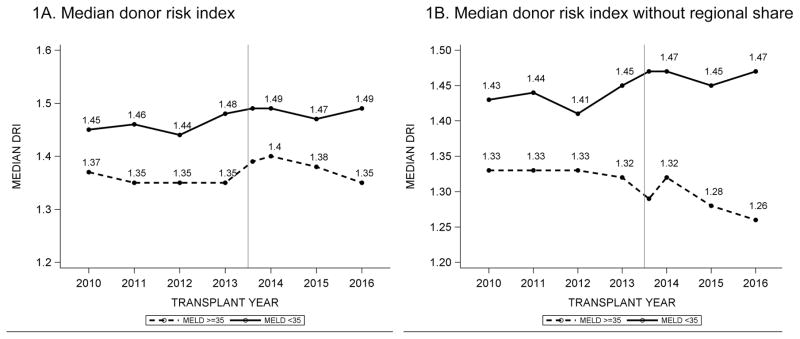

Overall, in the post-Share 35 era, donor organ quality improved for MELD ≥ 35 patients. After Share 35, patients with MELD ≥ 35 received livers from younger donors and fewer DCD livers. In contrast, patients with MELD < 35 received more DCD livers, as well as grafts with ≥ 30% macrosteatosis (Supplementary Figure). Figure 1A utilizes the median donor risk index to represent donor organ quality over time. In Figure 1B, the “regional share” component of DRI is taken out of the index, since policy-driven regional sharing in patients with MELD ≥ 35 makes that variable no longer relevant from the standpoint of organ quality. Without the regional share component, DRI improved by 0.04 points after Share 35 for the MELD ≥ 35 group. For patients with MELD < 35, DRI worsened by 0.03 points in the post-Share 35 era, with or without the regional sharing variable in the index.

Figure 1.

Trends in donor risk index (DRI), stratified by MELD ≥ 35 and < 35. The reference line is drawn at June 18, 2013, and a separate datapoint was created for transplants performed in 2013 but after June 18, 2013 in order to illustrate the trend after the implementation of Share 35. In Figure 1B, the “regional share” component of DRI is taken out of the index, since policy-driven regional sharing in patients with MELD ≥ 35 makes that variable no longer relevant from the standpoint of organ quality.

One-year patient and graft survival was 90.6% and 88.7%, respectively, compared to 89.9% and 87.7%, before the implementation of Share 35 (p<0.04 for both comparisons). Figure 2 displays Kaplan-Meier curves for one-year patient and graft survival, stratified by Share 35 era. Post-transplant survival improved significantly in the MELD ≥ 35 group, with improvement in one-year patient survival from 83.9% to 88.4% (p<0.01). There was no significant difference in the one-year patient (p=0.69) or graft (p=0.32) survival in patients with MELD < 35.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for 1-year patient survival and graft survival by MELD category, stratified by pre-Share 35 (dashed line) and post- Share 35 (solid line).

Table 3 summarizes the results of the Cox proportional hazards regression analyses for one-year patient and graft survival by MELD strata. In univariate analysis of recipient mortality at one year, Share 35 was associated with a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.93 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.86–1.00). In recipients with MELD ≥ 35, belonging in the post-Share 35 era was associated with a HR of 0.72 (95% CI 0.63–0.81).

Table 3.

Univariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis for 1-year patient survival, with pre-Share 35 era as reference. Bivariate Cox regression analysis performed with adjustment for donor risk index, with and without regional share. CI = confidence interval; DRI = donor risk index; LT = liver transplantation; MELD = Model for End-Stage Liver Disease.

| Hazard ratio (HR) for Share 35 | Unadjusted | +DRI | +DRI without regional share |

|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | |

| 1-year post-transplant mortality | |||

| All LT recipients | 0.93 (0.86–1.00) | 0.92 (0.86–0.99) | 0.92 (0.86–0.99) |

| Recipient MELD ≥ 35 | 0.72 (0.63–0.81) | 0.72 (0.63–0.81) | 0.72 (0.63–0.81) |

| Recipient MELD < 35 | 0.98 (0.89–1.07) | 0.98 (0.89–1.07) | 0.98 (0.89–1.07) |

| 1-year post-transplant graft failure | |||

| All LT recipients | 0.91 (0.85–0.97) | 0.90 (0.85–0.96) | 0.91 (0.85–0.97) |

| Recipient MELD ≥ 35 | 0.72 (0.64–0.81) | 0.72 (0.64–0.81) | 0.72 (0.64–0.81) |

| Recipient MELD < 35 | 0.96 (0.89–1.04) | 0.96 (0.89–1.04) | 0.96 (0.89–1.04) |

As the Share 35 policy resulted in a change in donor quality, bivariate analyses were performed to separate the effect of DRI on mortality. In patients with MELD ≥ 35, HR for one-year post-transplant mortality in the post-Share 35 era was 0.72 (95% CI 0.63–0.81) with DRI, with or without the regional sharing term. In patients with MELD < 35, 1-year mortality was not affected by Share 35, even after adjusting for DRI (HR 0.98, 95% CI 0.89–1.07). These results did not change substantially when waiting list time was added to the model.

In multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression analysis, which incorporated a wide array of recipient, donor, and transplant variables, Share 35 was associated with improved one-year patient survival in recipients with MELD ≥ 35 (HR 0.69, 95% CI 0.60–0.80) indicating a 30% reduction in mortality (Table 4). There was no statistically significant difference in one-year patient survival in recipients with MELD < 35 in the post-Share 35 era (HR 0.98, 95% CI 0.89–1.07). Other significant predictors of patient survival were DCD livers (HR 1.41, 95% CI 1.20–1.66), hospitalization in ICU at the time of LT (HR 2.20, 95% CI 1.94–2.48), and prior liver transplantation (HR 1.71, 95% CI 1.47–2.00). Older recipient and donor age, portal vein thrombosis, higher biochemical MELD score at time of LT, and transplantation in certain regions were also associated with an increased risk of one-year mortality. When the analysis was repeated incorporating donor macrosteatosis as a predictor, the impact of Share 35 did not change (data not shown). Multivariable regression models analyzing for one-year graft failure as the outcome yielded results similar to those for patient survival (Supplementary Table 3).

Table 4.

Multivariable Cox regression model for one-year post-transplant mortality, adjusted for region as well as donor, recipient, and transplant parameters.

| MELD ≥ 35 | MELD < 35 | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | |

|

| ||

| Share 35 | 0.69 (0.60–0.80) | 0.98 (0.89–1.07) |

|

| ||

| Recipient condition at time of transplant (Ref: Not hospitalized) | ||

| Hospitalized in ICU | 1.80 (1.40–2.30) | 2.23 (1.85–2.68) |

| Hospitalized, not in ICU | 1.18 (0.92–1.51) | 1.36 (1.19–1.54) |

|

| ||

| Prior liver transplantation | 1.62 (1.27–2.06) | 1.95 (1.58–2.42) |

|

| ||

| Recipient age (per 10-year increase) | 1.21 (1.13–1.29) | 1.28 (1.21–1.35) |

|

| ||

| BiochemicalMELD at LT (per 5-unit increase) | 1.00 (0.95–1.06) | 1.09 (1.04–1.13) |

|

| ||

| Donor age (per 10-year increase) | 1.08 (1.02–1.14) | 1.05 (1.02–1.09) |

|

| ||

| DCD liver | 1.78 (1.24–2.55) | 1.32 (1.10–1.58) |

|

| ||

| Cold ischemia time (per 1 hour) | 1.02 (1.00–1.05) | 1.03 (1.02–1.05) |

In addition to the variables listed, modelsincorporated donor sex, donor race, donor height, donor hepatitis C antibody or hepatitis B core antibody positive, donor hypertension, donor diabetes, donor ALT, split or partial liver transplantation, simultaneous liver-kidney transplantation, share type, region, and distance from transplant center, as well as recipient sex, race, MELD, BMI, etiology of liver disease, diabetes, dialysis at the time of transplant, exception case, exception points for HCC, portal vein thrombosis, and history of abdominal surgery.

Sensitivity analyses were performed to consider patient subtypes that may have influenced our results (Supplementary Table 4). Analyses stratifying for HCC and for simultaneous liver-kidney transplantation did not change the results. In contrast, patients with HCV experienced improved one-year patient survival in the post-Share 35 era regardless of MELD stratum. Other donor and recipient variables, including prior liver transplant, cold ischemia time, and the donor risk index, and region of transplant center, were tested for interaction with the post-Share 35 era, but were not found to be statistically significant. When the MELD < 35 group was stratified into MELD < 30 and MELD 30–34, results were similar — neither group experienced a difference in survival after the implementation of Share 35 (Table 5).

Table 5.

Univariate, bivariate, and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis for one-year patient survival by MELD category, with pre-Share 35 era as reference.

| Univariate Analysis | +Donor Risk Index | Multivariable | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-year post-transplant mortality | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) |

| Share 35 | |||

| MELD ≥ 35 | 0.72 (0.63–0.81)* | 0.70 (0.61–0.79)* | 0.71 (0.63–0.82)* |

| MELD 30–34 | 0.93 (0.78–1.11) | 0.92 (0.77–1.10) | 0.98 (0.82–1.17) |

| MELD < 30 | 0.99 (0.89–1.09) | 0.98 (0.89–1.09) | 0.96 (0.86–1.06) |

p<0.05

For the MELD ≥ 35 group, the improvement in one-year patient survival after Share 35 appeared to be driven by Regions 1, 3, 5, and 8 (Supplementary Table 5). No region experienced increased post-transplant mortality among recipients with MELD ≥ 35 after the implementation of Share 35. For patients with MELD < 35, there was no significant change in one-year survival after Share 35, in all regions.

Discussion

In this work, we find that implementation of Share 35 was associated with significantly improved one-year post-transplant survival, principally among recipients with MELD ≥ 35. The improvement is partly attributable to access to better organs for those recipients. On the other hand, there has been no apparent impact on one-year patient or graft survival in patients with MELD < 35, although they received higher-risk organs after Share 35.

The Share 35 policy implemented in June 2013 has had a number of impacts on the practice of liver transplantation in the US. Some of these were intended and expected consequences of the policy, including increased transplantation rates, shorter waitlist times, reduction in waitlist mortality, fewer organ discards, and increased organ offers for patients with MELD ≥ 35.(5, 7, 13–15) Using competing risks analysis, Edwards et al. demonstrated increased 90-day transplantation rates (66% versus 59%, p<0.05) and decreased waitlist mortality (25% versus 32%, p<0.05) for candidates with MELD ≥35 in the post-implementation era.(5) Other changes that have occurred since Share 35 may have been less predictable. In particular, reduction in donor acceptance rates has been criticized as an unintended consequence of this policy.(13, 16)

To our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically report the population impact of the Share 35 policy, with data encompassing several years before and after the policy change. Earlier analyses of the post-transplant outcome after Share 35 showed no differences in short term post-transplant graft survival.(5, 17) These ‘negative’ results may be attributed to smaller sample size or shorter follow-up than the current study. More recent analyses suggest that patients with MELD ≥ 40 experience improved graft and patient survival in the post-Share 35 era, whereas survival outcome of HCC patients has not been affected.(18, 19)

The Share 35 policy originated from the observation that patients with decompensated liver disease with MELD ≥ 35 experience higher waitlist mortality and similar post-transplant survival compared to status 1A LT candidates.(4) The anticipated benefit of the policy was that regional sharing would allow patients with MELD ≥ 35 to access a larger pool of organs. Prior to implementation of the policy, simulation modeling by the SRTR predicted an increase in the rate of transplantation for patients with MELD ≥ 35.(20) Our data show that the policy had a significant impact on the quality of organs accepted for both patients with MELD ≥ 35 and MELD < 35. It is well accepted that that patients with high MELD do poorly with inferior grafts (21), and our data suggest that transplant surgeons and physicians took advantage of higher quality organs made available as a result of the Share 35 policy to preserve acceptable outcomes for high MELD patients. Although it has been debated to what extent the utilization of lesser quality organs influences survival benefit in low MELD patients (22, 23), it is encouraging that the shift in DRI for patients with MELD < 35, including those with MELD of 30–34, has not materialized into a demonstrable detriment in outcome (24–26).

Our analysis provides helpful insight regarding the DRI. While many of the characteristics of donor organs accepted for patients with MELD ≥ 35 pointed in a favorable direction, the median DRI increased in the post-Share 35 era for the MELD ≥ 35 category. This was attributable to the fact that there were significantly more regional shares — a component of the DRI that contributes to the score independent of the cold ischemia time. In previous eras, regionally shared organs may have represented less desirable organs that were declined locally before being offered regionally. Without the regional share component, the median DRI improved for recipients with MELD ≥ 35 in the post-Share 35 era.

As seen in Table 3, the extent to which DRI accounted for the improvement in post-transplant outcomes in high MELD patients was relatively small, which may indicate that there are other relevant donor/transplant factors that are not captured by DRI. In addition, some of the benefit may be attributable to the shortened waiting time for these critically ill patients. A higher percentage of liver transplants are being performed in patients with MELD ≥ 35, and LT recipients are more often hospitalized in the ICU at the time of LT. These patients are at high risk for frailty and functional impairment, which are predictors of post-transplant mortality.(27) These complications may be mitigated by shorter waitlist times and increased organ availability in the post-Share 35 era. Improved candidate fitness at the time of LT as a result of this policy change may contribute to better post-transplant outcomes.

We conducted sensitivity analyses to evaluate the possible impact of concurrent advances in the care of patients with liver disease, as the improvement in survival may not be due to the Share 35 policy alone. Quality of peri-operative and post-transplant care may have also improved. However, if this were the primary cause, a similar overall improvement among patients with lower MELD would be expected. This was observed only among patients with HCV — reflective of the widespread availability of effective antiviral therapy in recent years.

There was no difference in post-transplant survival among the MELD 30–34 group, suggesting that there would be little benefit from wider sharing at a lower MELD threshold. We also noted regional variation in post-transplant outcomes after Share 35, with certain regions contributing more than others to the observed difference in improved post-transplant survival among the MELD ≥ 35 group. However, no region experienced increased post-transplant mortality, either in recipients with MELD ≥ 35 or MELD < 35.

In summary, in the post-Share 35 era, patients with MELD ≥ 35 benefit from shorter waitlist times and access to higher quality donor organs, leading to improved post-transplant survival. Although patients with MELD < 35 received higher-risk organs, it does not appear that their post-transplant outcomes have been compromised. In light of the rapidly changing landscape of liver transplantation in the US, whether the changes seen in this analysis will remain in the future is unknown. The results of our analysis, however, suggest that the policy change has resulted in better donor-recipient matching and, ultimately, significantly improved recipient outcomes in the US, particularly in patients with advanced liver failure in desperate need of liver transplantation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This work was supported in part by a grant from the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Disease (DK-34238, 99236 and 007056). The funding organization played no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

List of Abbreviations

- LT

Liver transplantation

- MELD

Model for End-Stage Liver Disease

- OPTN

Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network

- DRI

donor risk index

- DCD

donation after cardiac death

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: All authors declare that they have no financial, professional, or personal conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Kamath PS, Wiesner RH, Malinchoc M, Kremers W, Therneau TM, Kosberg CL, D’Amico G, et al. A model to predict survival in patients with end-stage liver disease. Hepatology. 2001;33:464–470. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.22172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freeman RB, Wiesner RH, Edwards E, Harper A, Merion R, Wolfe R UNOS/OPTN Liver and Transplantation Committee. Results of the first year of the new liver allocation plan. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:7–15. doi: 10.1002/lt.20024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Washburn K, Harper A, Klintmalm G, Goss J, Halff G. Regional sharing for adult status 1 candidates: reduction in waitlist mortality. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:470–474. doi: 10.1002/lt.20768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharma P, Schaubel DE, Gong Q, Guidinger M, Merion RM. End-stage liver disease candidates at the highest model for end-stage liver disease scores have higher wait-list mortality than status-1A candidates. Hepatology. 2012;55:192–198. doi: 10.1002/hep.24632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edwards EB, Harper AM, Hirose R, Mulligan DC. The impact of broader regional sharing of livers: 2-year results of “Share 35”. Liver Transpl. 2016;22:399–409. doi: 10.1002/lt.24418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chapman WC. The new lottery ticket: Share 35. Liver Transpl. 2016;22:393–395. doi: 10.1002/lt.24420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Massie AB, Chow EK, Wickliffe CE, Luo X, Gentry SE, Mulligan DC, Segev DL. Early changes in liver distribution following implementation of Share 35. Am J Transplant. 2015;15:659–667. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Annamalai A, Ayoub W, Sundaram V, Klein A. First Look: One Year Since Inception of Regional Share 35 Policy. Transplant Proc. 2015;47:1585–1590. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldberg DS, Karp S. Outcomes and disparities in liver transplantation will be improved by redistricting-cons. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2016 doi: 10.1097/MOT.0000000000000390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halazun KJ, Mathur AK, Rana AA, Massie AB, Mohan S, Patzer RE, Wedd JP, et al. One Size Does Not Fit All--Regional Variation in the Impact of the Share 35 Liver Allocation Policy. Am J Transplant. 2016;16:137–142. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng S, Goodrich NP, Bragg-Gresham JL, Dykstra DM, Punch JD, DebRoy MA, Greenstein SM, et al. Characteristics associated with liver graft failure: the concept of a donor risk index. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:783–790. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bambha KM, Dodge JL, Gralla J, Sprague D, Biggins SW. Low, rather than high, body mass index confers increased risk for post-liver transplant death and graft loss: Risk modulated by model for end-stage liver disease. Liver Transpl. 2015;21:1286–1294. doi: 10.1002/lt.24188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Washburn K, Harper A, Baker T, Edwards E. Changes in liver acceptance patterns after implementation of Share 35. Liver Transpl. 2016;22:171–177. doi: 10.1002/lt.24348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim WR, Lake JR, Smith JM, Skeans MA, Schladt DP, Edwards EB, Harper AM, et al. Liver. Am J Transplant. 2016;16(Suppl 2):69–98. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chow EK, Massie AB, Luo X, Wickliffe CE, Gentry SE, Cameron AM, Segev DL. Waitlist Outcomes of Liver Transplant Candidates Who Were Reprioritized Under Share 35. Am J Transplant. 2017;17:512–518. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldberg D, Gilroy R, Karp S, Levine M, Abt P. Interaction of MELD score and Share 35 era on organ offer acceptance rates for the highest-ranked patients on the liver transplant waitlist. Hepatology. 2016;64 Plenary and Parallel Sessions (Abstracts 1–258) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nicolas CT, Nyberg SL, Heimbach JK, Watt K, Chen HS, Hathcock MA, Kremers WK. Liver transplantation after share 35: Impact on pretransplant and posttransplant costs and mortality. Liver Transpl. 2017;23:11–18. doi: 10.1002/lt.24641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nekrasov V, Matsuoka L, Rauf M, Kaur N, Cao S, Groshen S, Alexopoulos SP. National Outcomes of Liver Transplantation for MELD ≥ 40: The Impact of Share 35. Am J Transplant. 2016 doi: 10.1111/ajt.13823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Croome KP, Lee DD, Harnois D, Taner CB. Effects of the Share 35 Rule on Waitlist and Liver Transplantation Outcomes for Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0170673. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson D, Waisanen L, Wolfe R, Merion RM, McCullough K, Rodgers A. Simulating the allocation of organs for transplantation. Health Care Manag Sci. 2004;7:331–338. doi: 10.1007/s10729-004-7541-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nemes B, Gelley F, Zádori G, Piros L, Perneczky J, Kóbori L, Fehérvári I, et al. Outcome of liver transplantation based on donor graft quality and recipient status. Transplant Proc. 2010;42:2327–2330. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schaubel DE, Sima CS, Goodrich NP, Feng S, Merion RM. The survival benefit of deceased donor liver transplantation as a function of candidate disease severity and donor quality. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:419–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.02086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Croome KP, Marotta P, Wall WJ, Dale C, Levstik MA, Chandok N, Hernandez-Alejandro R. Should a lower quality organ go to the least sick patient? Model for end-stage liver disease score and donor risk index as predictors of early allograft dysfunction. Transplant Proc. 2012;44:1303–1306. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2012.01.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grąt M, Wronka KM, Patkowski W, Stypułkowski J, Grąt K, Krasnodębski M, Masior Ł, et al. Effects of Donor Age and Cold Ischemia on Liver Transplantation Outcomes According to the Severity of Recipient Status. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61:626–635. doi: 10.1007/s10620-015-3910-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Briceño J, Ciria R, de la Mata M, Rufián S, López-Cillero P. Prediction of graft dysfunction based on extended criteria donors in the model for end-stage liver disease score era. Transplantation. 2010;90:530–539. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181e86b11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schlegel A, Linecker M, Kron P, Györi G, De Oliveira ML, Müllhaupt B, Clavien PA, et al. Risk Assessment in High- and Low-MELD Liver Transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2016 doi: 10.1111/ajt.14065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dolgin NH, Martins PN, Movahedi B, Lapane KL, Anderson FA, Bozorgzadeh A. Functional status predicts postoperative mortality after liver transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2016;30:1403–1410. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.