Abstract

Child sexual abuse (CSA) is identified as a significant risk factor for later victimization in the context of adult intimate relationships, but less is known about the risk associated with CSA in early romantic relationships. This paper aims to document the association between CSA and teen dating victimization in a large representative sample of Quebec high-school students. As part of the Youths’ Romantic Relationships Project, 8,194 teens completed measures on CSA and psychological, physical and sexual dating violence. After controlling for other interpersonal traumas, results show that CSA contributed to all three forms of dating victimization among both boys and girls. The heightened risk of revictimization appears to be stronger for male victims of CSA. Intervention and prevention efforts are clearly needed to reduce the vulnerability of male and female victims of sexual abuse who are entering the crucial phase of adolescence and first romantic relationships.

Keywords: sexual abuse, dating violence, interpersonal trauma, revictimization

Child sexual abuse (CSA) is internationally recognized as significant public health issue (Anda et al., 2006; World Health Organization, 2006). According to a meta-analysis of 217 studies from various countries published between 1980 and 2008, the prevalence of sexual abuse before the age of 18 is estimated at 18% for women and 7.6 % for men (Stoltenborgh, van IJzendoorn, Euser, & Bakermans-Kranenburg, 2011).

Past studies have shown unequivocally that a history of sexual abuse increases the likelihood of lifetime psychopathology (MacMillan et al., 2014) often characterized by posttraumatic stress symptoms, depression, substance abuse and dissociation. A particularly alarming outcome of CSA is increased suicidal ideations and suicide attempts, with stronger associations found among males than females (Bhatta, Jefferis, Kavadas, Alemagno, & Shaffer-King, 2014; Martin, Bergen, Richardson, Roeger, & Allison, 2004). However, what remains less documented are the shorter-term outcomes associated with CSA, more specifically those experienced during adolescence. This age group is of particular interest since it is during this developmental period that youth experience their first romantic relationships, with accompanying challenges related to intimacy and sexuality. Such developmental changes can prove to be particularly difficult for sexually abused youth since they can trigger a resurgence of negative emotions and reactions related to the trauma (Wekerle & Wolfe, 2003). Victims of CSA often develop feelings of shame, self-blame and powerlessness that can persist long after the abuse and shape the way they interpret and react to social cues (Feiring, Simon, Cleland, & Barrett, 2013). In addition, feelings of stigmatization can disrupt the development of efficient self-protection strategies and interpersonal skills, including problem-solving and conflict resolution (Banyard, Arnold, & Smith, 2000; Feiring & Cleland, 2007). Thus, CSA can hinder victims’ ability to adequately manage and identify high-risk situations and violent behaviors, subsequently putting them at risk for revictimization in their dating relationships.

The issue of revictimization is well documented among adult populations and recent efforts have begun investigating this phenomenon in adolescents. In order to better understand the mechanisms associated with revictimization, researchers have proposed conceptual models. Some models are more integrative, such as those based on socio-ecological approaches (Grauerholz, 2000) or on risk and vulnerability factors (Messman-Moore & Long, 2003), and consider various personal, interpersonal and sociocultural factors that may increase the risk for subsequent victimization. Other models, like the traumagenic dynamics model developed by Finkelhor and Browne (1985), focus more on specific processes related to the individual sphere that are caused by the traumatic experience itself (i.e. traumatic sexualization, betrayal, powerlessness, and stigmatization/self-blame) and that may be linked to heightened vulnerability in CSA survivors.

That said, very few existing models have attempted to explain revictimization during adolescence. One such model proposed by Noll and Grych (2011) analyzes the biological stress response with cognitive, affective and behavioral factors involved in adaptive responses to sexual threats. This Read-React-Respond model (Noll & Grych, 2011) postulates that preventive skills can be modified and developed in victims of CSA. In order to prevent revictimization, the individual must first be able to adequately "read" potentially dangerous situations, in turn they must then "react" appropriately (fight or flight) and, finally, "respond" effectively to potential threats. The authors posit that the absence of these three abilities is associated with an increased relational vulnerability. This model is of significant interest in the development of efficient intervention strategies to reduce the risk of future sexual assaults among victims of CSA. Hébert, Daigneault and Van Camp (2012) proposed a comprehensive revictimization model that considers the variables related to the victim, the aggressor, and the interaction between individual, relational, community and societal factors. Yet, some factors of this inclusive model still await further investigation before it can be fully applied. It is to be noted that these models were mainly derived from studies involving female participants due in large part to the absence of sufficient empirical data available for adolescent boys.

Consistent with these theoretical models, previous research on adult samples has clearly established the association between CSA and risk of revictimization in adulthood (Afifi et al., 2009; Chan, Yan, Brownridge, Tiwari, & Fong, 2011; Coid et al., 2001; Daigneault, Hébert, & McDuff, 2009; DiLillo, Giuffre, Tremblay, & Peterson, 2001; Messman-Moore & Long, 2000; Ports, Ford, & Merrick, 2016) and, more specifically, with intimate partner violence (for a review see Capaldi, Knoble, Shortt, & Kim, 2012). However, just as with the theories, the majority of these studies have focused primarily on samples of female participants. Findings from the Canadian General Social Survey, which included both genders (9,170 women and 7,823 men), highlighted that both sexually abused men and women are at an increased risk of being victimized by their intimate partners (Daigneault et al., 2009). In regards to men’s experiences specifically, those who reported CSA were more likely to sustain psychological (OR = 1.9) and physical (OR = 3.0) violence from a current or previous partner compared to male non-victims of CSA. Due to sample size restrictions, the association between CSA and sexual violence could not be evaluated. However, this association was established by Hines (2007) who reported in her sample of 7,667 college students from 38 sites that, among men, CSA was a significant risk factor for forced sexual coercion by an intimate partner. A main conclusion of this study was that sexual revictimization among victims of CSA is a cross-gender, cross-cultural phenomenon. Similarly, in their sample of 209 female undergraduate students, Banyard et al. (2000) found that CSA victims were twice as likely to sustain physical abuse and three times more likely to experience psychological abuse from their dating partner, even after controlling for the presence conflict in the family of origin. That said, much less is known on the potential pathways from CSA to teen dating violence.

Overall, prevalence rates of teen dating violence victimization range from 20% to 50% with higher rates found among girls (Foshee et al., 2011; Pica et al., 2012; Wolitzky-Taylor et al., 2008). Recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2013 National Youth Risk Behavior Survey (Vagi, O’Malley Olsen, Basile, & Vivolo-Kantor, 2015) assessed the prevalence of dating victimization in the past 12 months among 9,900 high-school students. Prevalence rates of all forms of dating violence victimization were found to be higher among teenage girls than for boys, namely physical only (6.6% vs. 4.1%), sexual only (8.0% vs. 2.9%), both physical and sexual (6.4% vs. 3.3%) and either physical or sexual (20.9% vs. 10.4%).

Recent studies have shown that a history of CSA is associated with an increased risk of experiencing continued victimization in interpersonal relationships, including dating relationships (Feiring et al., 2013; Gagné, Lavoie, & Hébert, 2005; Hamby, Finkelhor, & Turner, 2012; Hébert, Lavoie, & Blais, 2014a; Shorey, Zucosky, Febres, Brasfield, & Stuart, 2013). Yet, as with adult samples, the bulk of studies have focused largely on samples of girls and few have conducted specific analyses for boys. Results from a study of 160 youth victims of CSA found that the majority of participants (80%) endorsed at least one type of dating violence victimization, with more reports of verbal than physical aggression (79% vs. 24%) (Feiring et al., 2013). However, the sample was predominantly comprised of adolescents from child protection services as well as of girls (73%). In another study using a CPS sample of 126 girls 13 to 17 years of age, psychological violence was endorsed by 90% of all victims and nearly half reported sustaining physical violence by a romantic partner. Duration of the CSA and presence of violence or completed intercourse were found to predict later dating victimization above and beyond other risk factors (Cyr, McDuff, & Wright, 2006). That said, when interpreting results from studies using CPS samples, it is important to remember that youth in such services often present higher rates of overall childhood maltreatment than those from the general population (Wekerle et al., 2001).

When considering studies including only female teenagers from community samples, a history of CSA was found to be associated with higher prevalence of all forms of dating violence (psychological, physical and sexual), with nearly half (46.7%) of adolescent CSA victims reporting at least one form of dating victimization, compared to 24.2% of non-CSA teenagers (Hébert, Lavoie, Vitaro, McDuff, &Tremblay, 2008). In another study, adolescent female victims of intra-familial sexual abuse were four times more likely than non-victims to have experienced psychological violence in their romantic relationships and 3 times more likely for physical violence (Tourigny, Lavoie, Vézina, & Pelletier, 2006). Although this information is of great value in better understanding the association between CSA and dating violence, the possible link has yet to be documented among teenage boys in large community samples.

Contextual variables contributing to revictimization in romantic relationships also have been examined among adults and young adults. For example, exposure to interparental violence and childhood physical abuse are identified as significant predictors of partner violence (both perpetration and victimization) (O’Donnell et al., 2006; Simonelli, Mullis, Elliott, & Pierce, 2002; Whitfield, Anda, Dube, & Felitti, 2003). This is in line with social learning theories which advance that child maltreatment and exposure to violence can influence acceptance of violence, whereby learned patterns of aggression are repeated in later interpersonal relationships (Wolfe & Wekerle, 1997). In addition, it has been proposed that cumulative traumas experienced in childhood can increase the risk of being victimized by a romantic partner or other individuals (Ports et al., 2016; Whitfield et al., 2003). More specifically, results from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study conducted among 8,629 adults, indicated that childhood sexual abuse, physical abuse and witnessing interparental violence increased the risk of victimization by a partner two-fold. When all three traumas are present, women were 3 times more likely and men almost four times to experience intimate partner violence (Whitfield et al., 2003).

This brief summary on the existing literature underlines the paucity of research that exists on the association between CSA and subsequent dating victimization in adolescence, especially in regards to the experiences of adolescent boys. The few studies that have considered both genders have not conducted separate analyses for boys and girls precluding the identification of specific risk factors. In regards to teen dating violence, several studies did not distinguish the different forms of victimization (psychological, physical and sexual dating victimization). In addition, the majority of studies conducted on the interrelation of CSA and dating victimization omitted from consideration other forms of interpersonal traumas sustained in childhood, such as witnessing violence, that are found to be associated with dating victimization. Furthermore, most studies are based either on convenience samples or small clinical samples. Against this backdrop, the present study aims to (1) determine the prevalence rates of dating violence victimization among CSA victims of both genders, and (2) investigate the association of CSA with different forms of dating violence (psychological, physical and sexual) while controlling for sociodemographic characteristics and other childhood interpersonal traumas (witnessing violence against someone, exposure to interparental violence and physical abuse) within a large representative sample of high school students.

Method

Participants

Data collected in the Quebec Youths’ Romantic Relationships Project (YRRP) were used for this study. The YRRP is a longitudinal study that aims to document dating violence among youths aged 14 to 18 and the associated risk factors and consequences. During the first wave of the study, participants were recruited by using a one-stage stratified cluster sampling of high schools. Schools were randomly selected from an eligible pool from the Quebec ministry of Education. To obtain a representative sample of students in grades 10 through 12, schools were first classified into 8 strata according to metropolitan geographical area, status of schools (public or private schools), teaching language (French or English) and social economic deprivation index.

A total of 34 schools participated in the survey. Class response rates and the overall student response rate were determined as the ratio between the number of students that accepted to participate (students from whom written consent was obtained) and the number of solicited students, calculated per class and for the entire set of participants respectively. A response rate of 100% was obtained for the majority (320/329) of classes; while for the remaining, the response rate ranged from 90% to 98%. The overall response rate obtained was of 99%. The total sample is comprised of 8,194 youths. The sample was weighed in order to account for sampling bias. For a participant in any given grade, the sample weight was defined as the inverse of the probability of selecting the given grade in the respondent’s stratum in the sample multiplied by the probability of selecting the same grade in the same stratum in the population. The weighed sample size consists of 6,531 youths. The present analyses rely on the weighed sample of participants from the first wave.

Measures

Sexual abuse

A history of sexual abuse was measured using two item stems adapted from Finkelhor, Hotaling, Lewis and Smith (1990), as used in a representative survey with adults in the province of Quebec (Tourigny, Hébert, Joly, Cyr, & Baril, 2008). The first item stem assesses unwanted sexual touching (“Have you ever been touched sexually when you did not want to, or have you ever been manipulated, blackmailed, or physically forced to touch sexually…”) and, the second, unwanted sexual intercourse involving penetration (“Excluding the sexual touching mentioned in the previous item, has anyone ever used manipulation, blackmail, or physical force, to force or obligate you to have sex (including sexual activities involving oral, vaginal or anal penetration…”). Each item stem was used in relation to different perpetrators (member of the immediate or extended family, known person outside the family (other than a boyfriend or girlfriend) and a stranger). A dichotomized sexual abuse score was derived based on whether any form of sexual abuse occurred or not.

Other interpersonal traumas

The study documented other adverse life experiences, including exposure to interparental violence, being physically abused by a family member or witnessing violence against someone else. A version of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2) (Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996) was adapted in order to measure exposure to interparental violence. This scale assessed whether a youth witnessed interparental psychological violence as well as physical violence from the father towards the mother and vice versa. For example, psychological and physical violence items are formulated as follows: “In my lifetime, I’ve seen my father do this to my mother… Insult, swear, shout, yell or “Push, shove, slap, twist the arm, throw something that could hurt”. Two questions from the Early Trauma Inventory Self-report - Short form (ETISR-SF) (Bremner, Bolus, & Mayer, 2007) allowed to measure physical abuse “Have you ever been physically hit by a member of your family?” and witnessing violence against someone “Have you ever witnessed violence against someone, including a member of your family?”.

Dating violence

Participants completed an adapted version the Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory (CADRI) (Fernández-González, Wekerle, & Goldstein, 2012; Wolfe et al., 2001) to assess dating violence experienced in the past 12 months. Three items were used to measure psychological violence (e.g., In the past 12 months, how often did the following situations occur during a conflict or argument with your boyfriend or girlfriend… Ridiculed or made fun of you in front of others) and 3 items were used to evaluate physical violence sustained in the past year (e.g. Kicked, hit or punched you). Sexual dating violence was assessed using 9 items from the revised version of the Sexual Experiences Survey (SES) (Koss et al., 2007; Koss & Gidycz, 1985; Koss & Oros, 1982). An example of an item is: “In the past 12 months, how often did your boyfriend or girlfriend… Tried to have sex with you when you did not want to by using some physical force to force you”. Response options were based on a 4-point Likert scale: Never, 1 to 2 times, 3 to 5 times, and 6 times or more. For physical and sexual dating violence, we created dichotomized scores of dating violence according to whether the participant reported at least one episode or more (1) or not (0). For psychological violence, items were treated according to minor or severe acts. The first item, “Said things just to make you angry”, was considered as a minor act while the two other items “Ridiculed or made fun of you in front of others” and “Kept track of who you were with and where you were” were treated as severe acts. First, reports of minor act were dichotomized according to whether participants reported the related gestures occurred 3 to 5 times and more (1) or not (0) while reports of severe acts were dichotomized if they occurred 1 or more times (1) or not. Then, a dichotomized score was created for psychological violence.

Sociodemographic variables

Participants also completed information on sex, age, grade level, language spoken at home (French, English, or other), family structure (living with both parents under the same roof, living both parents in different households (shared custody), living with one parent, other family structure arrangements), and education and ethnicity of parents.

Procedure

Research assistants presented the study’s goals in class. Participants agreed to participate on a voluntary basis by signing a consent form that stated they could withdraw from the study at any time without any prejudice. The internal review board of the Université du Québec à Montréal approved this project.

Results

Results will be presented in three sections. First, the sociodemographic information for the sample will be summarized. Second, results of bivariate analyses exploring the link between CSA and dating victimization will be presented. Finally, results of logistic regressions exploring whether CSA contributed to the prediction of each form of dating violence while controlling for sociodemographics and other childhood interpersonal traumas experienced, will be summarized. Analyses were conducted using Stata (Statacorp, 2011).

Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. Teenagers were for the majority French-speaking with 75.40% reported speaking only French at home, 3.62% only English, 5.08% both French and English, and 15.90%, other languages. A total of 63.21% lived with both parents, while 34.64% lived either in single-parent families or in shared custody and 2.15% described another living arrangement (living in foster case, with a member of the extended family). Whereas 66.67% of youth reported their mother had a college or university degree, 58.35% reported the same for the level education of their father. Among youth included in the study, 72.26% youth (or their parents) were from Quebec or Canada while 27.74% of adolescents reported other ethnicities (Latino-American or African-American, North African or Middle Eastern European, Asian or mixture of ethnicities).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Sample

| Girls (%) | Boys (%) | Total (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grade level | |||

| Grade 10 | 34.07 | 41.11 | 37.03 |

| Grade 11 | 32.30 | 30.14 | 31.39 |

| Grade 12 | 33.63 | 28.75 | 31.58 |

| Language spoken | |||

| French only | 73.81 | 77.58 | 75.40 |

| English only | 3.30 | 4.06 | 3.62 |

| French and English | 5.07 | 5.10 | 5.08 |

| Other | 17.82 | 13.26 | 15.90 |

| Lives with… | |||

| Both parents under the same roof | 62.46 | 64.24 | 63.21 |

| Separated parents/Joint custody | 11.82 | 13.97 | 12.73 |

| Mother or father | 23.57 | 19.65 | 21.91 |

| Other | 2.15 | 2.14 | 2.15 |

| Mother’s level of education | |||

| High school or less | 28.93 | 29.74 | 29.27 |

| College or professional training | 37.73 | 32.70 | 35.63 |

| University | 33.34 | 37.56 | 35.10 |

| Father’s level of education | |||

| High school or less | 36.37 | 36.46 | 36.41 |

| College or professional training | 30.15 | 30.28 | 30.21 |

| University | 33.48 | 33.26 | 33.38 |

| Ethnicity of parents | |||

| Québécois or Canadian | 68.10 | 74.09 | 70.62 |

| Latino-American or African-American | 4.96 | 4.00 | 4.56 |

| North African or Middle Eastern | 4.58 | 4.29 | 4.46 |

| European | 3.36 | 3.59 | 3.46 |

| Asian | 4.23 | 2.90 | 3.67 |

| Other1 | 14.77 | 11.13 | 13.23 |

Other combines all unlisted ethnicities or possible combinations of listed ethnicities for both parents.

About half (52.63%) of participants reported having had a dating relationship in the last 12 months, with 55.45% girls and 48.78% of boys. Subsequent analyses are based on this sample of teens reporting dating. To analyze gender differences in prevalence, the Pearson χ2 statistic was corrected for the survey design with the second-order correction of Rao and Scott and was converted into an F (Fisher) statistic with an F statistic reported for differences between categorical indicators (Rao & Scott 1981; 1984).

Overall, 33.09% of youths reported having experienced psychological violence in their romantic relationship during the last year. A total 14.59% of youths reported physical violence while 14.64% reported at least one episode of sexual violence by their romantic partner in the past 12 months. The prevalence of CSA for teens reporting dating was 14.77%. CSA was found to be significantly higher for girls (20.73%) than for boys (5.34%) (F(1,26) = 79.77, p < .0001).

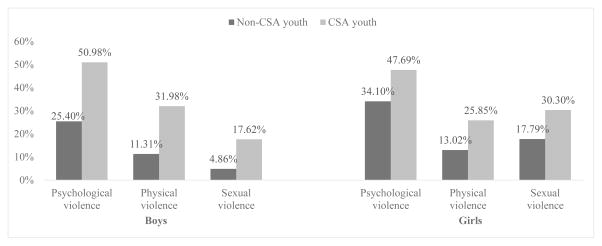

Cross-tabulation results between CSA and the different forms of dating violence by gender are presented in Figure 1. Compared to non-CSA teenagers, prevalence rates of teen dating violence were significantly higher among CSA youths. Indeed, close to half (47.69%) of girl victims of CSA reported experiencing psychological dating violence compared to 34.10% of non-CSA girls, F(1,26) = 26.38, p = .001. In the same way, half (50.98%) of CSA boys reported psychological violence by a romantic partner in the past year compared to 25.40% of non-CSA boys (F(1,23) = 16.02, p = .0006). The difference was even more striking for physical and sexual dating violence, where the prevalence was twice as high among victims of CSA. Whereas 13.02% of non-CSA girls reported physical victimization by a romantic partner, the rate increased to 25.85% for CSA girls (F(1,26) = 36.85, p < .0001). For boys, the difference was even more marked as 11.31% of non-CSA boys reported physical victimization by a romantic partner, but the prevalence was close to 3 times the rate (31.98%) for CSA boys (F(1,23) = 21.03, p = .0001). Finally, close to a third (30.30%) of CSA girls reported sexual dating violence, compared to 17.79% of non-CSA girls (F(1,26) = 25.21, p < .0001. CSA boys (17.62%) reported rates of sexual victimization by a romantic partner close to 4 times those reported by non-CSA boys (4.85%) (F(1,23) = 26.82, p < .0001).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of Different Forms of Dating Violence by History of Child Sexual Abuse and Gender

Within the CSA group, prevalence rates of dating victimization were similar for boys and girls for psychological victimization (F(1,23) = 0.17, ns) and physical (F(1,23) = 0.95, ns) victimization by a romantic partner, while it was marginally significant for sexual victimization (F(1,23) = 3.74, p = .06). By contrast, within the non-CSA group, gender disparity was evident for all forms of dating victimization with girls (34.10%) more likely to report sustaining psychological violence than non-CSA boys (25.40%) (F(1,26) = 36.56, p < .0001). Non-CSA girls (13.02%) were also more likely than non-CSA boys (11.31%) to experience physical violence in the past 12 months (F(1,26) = 4.48, p < .05) and to experience sexual violence by a romantic partner (17.79% vs. 4.86%) (F(1,26) = 111.96, p < .0001).

Table 2 summarizes the results of the logistic regressions carried out for each form of violence (psychological, physical and sexual) for girls and boys. For girls, the three models were significant. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test was performed to test the model fit with a non-significant p value suggesting a good fit. The results for the three models showed a good fit (Hosmer-Lemeshow p value = .47, .60 and .07 respectively for psychological, physical and sexual violence models).

Table 2.

Logistic Regression Predicting Different Forms of Dating Violence Among Girls and Boys

| Psychological violence

|

Physical violence

|

Sexual violence

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | p value | [98% CI] | OR | p value | [98% CI] | OR | p value | [98% CI] | |

| Girls | F(14,13) = 15.39, p = .0001 | F(14,13) = 9.23, p = .0001 | F(14,13) =10.12, p = .0001 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| CSA | 1.41 | 0.01 | [1.10 – 1.81] | 1.88 | < 0.001 | [1.42 – 2.49] | 1.69 | < 0.001 | [1.30 – 2.20] |

| Witness | 1.45 | < 0.001 | [1.17 – 1.78] | 1.47 | 0.04 | [1.03 – 2.12] | 1.25 | 0.11 | [0.95 – 1.64] |

| PA | 0.98 | 0.88 | [0.78 – 1.24] | 1.10 | 0.58 | [0.78 – 1.54] | 1.30 | 0.05 | [1.00 – 1.70] |

| IPV Psy | 1.39 | 0.01 | [1.10 – 1.77] | 1.28 | 0.23 | [0.85 – 1.91] | 1.39 | 0.05 | [1.00 – 1.93] |

| IPV Phy | 1.15 | 0.20 | [0.93 – 1.43] | 1.19 | 0.32 | [0.83 – 1.69] | 1.12 | 0.46 | [0.83 – 1.50] |

|

| |||||||||

| Boys | F(14,10) = 4.89, p = .008 | F(14,10) = 6.63, p = .0024 | F(12,12) = 2.85, p = .041 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| CSA | 2.53 | 0.01 | [1.31 – 4.90] | 2.15 | 0.03 | [1.11 – 4.15] | 3.35 | 0.01 | [1.50 – 7.48] |

| Witness | 1.70 | < 0.001 | [1.23 – 2.35] | 1.46 | 0.05 | [1.00 – 2.15] | 1.21 | 0.40 | [0.76 – 1.93] |

| PA | 0.98 | 0.91 | [0.67 – 1.42] | 1.30 | 0.08 | [0.97 – 1.74] | 2.30 | < 0.001 | [1.40 – 3.77] |

| IPV Psy | 1.57 | < 0.001 | [1.18 – 2.07] | 0.89 | 0.39 | [0.67 – 1.18] | 1.83 | 0.09 | [0.90 – 3.70] |

| IPV Phy | 0.98 | 0.94 | [0.61 – 1.57] | 1.48 | 0.11 | [0.90 – 2.42] | 0.95 | 0.86 | [0.51 – 1.76] |

Note. Model controlled for age, education level, language spoken and family structure.

CSA = Child sexual abuse, PA = Physical abuse, Witness = Witnessing violence, IPV Psy = Exposure to interparental psychological violence, IPV Phy = Exposure to interparental physical violence

For girls, witnessing violence against someone (OR = 1.45, p < .001) and exposure to psychological interparental violence (OR = 1.39, p = .01) were significantly associated with psychological victimization in the context of dating relationships. While only witnessing violence against someone (OR = 1.47, p = .04) was found significant in the prediction of physical violence; sustaining sexual violence by a romantic partner was predicted by physical abuse (OR = 1.30, p = .05) and exposure to psychological interparental violence (OR = 1.39, p = .01). After controlling for socio-demographic characteristics (age, education level, language spoken and family structure) and interpersonal traumas, CSA significantly contributed to increasing the odds of sustaining all three forms of dating violence by a romantic partner in the past year (OR = 1.41, 1.88 and 1.69 for psychological, physical and sexual dating violence respectively).

The three models for boys were also significant. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test suggested a good fit for the psychological and physical violence models (p value = .15 and .90 respectively) and a less good fit for the sexual violence model (p < .001). To overcome this issue, the model was re-estimated by removing the least significant control variable (family structure) resulting in a non-significant Hosmer-Lemeshow test (p = .81) suggesting a good fit.

For boys, witnessing violence against someone (OR = 1.70, p < .001) and exposure to psychological interparental violence (OR = 1.57, p < .001) predicted psychological dating violence. Witnessing violence against someone (OR = 1.46, p = .05) predicted occurrence of physical violence by a romantic partner. Physical abuse was associated with a two-fold increased risk for sexual violence by a romantic partner (OR = 2.30, p < .001).

After controlling for socio-demographic characteristics (age, education level, language spoken and family structure) and other interpersonal traumas, a history of CSA among boys significantly contributed to all three forms of dating violence. CSA was thus associated with a two- to threefold likelihood of sustaining psychological (OR = 2.53, p = .01), physical (OR = 2.15, p = .03) and sexual violence (OR = 3.35, p = .01) by a romantic partner in the past 12 months.

Discussion

The first aim of this study was to assess the prevalence of different forms of dating victimization among adolescent girls and boys victims of CSA using a representative sample of Quebec high school students ages 14–18. Overall, dating violence was quite prevalent in the present sample of adolescents, with roughly 42% of youth in couples reporting at least one form of dating victimization during the past 12 months. Psychological violence was by far the most reported form of dating violence by both boys and girls, as well as victims of CSA and non-victims alike.

In accordance with past findings, overall rates of dating victimization were significantly higher among CSA victims than non-victims for all forms of dating victimization (Banyard et al., 2000; Cyr et al., 2006; Hébert et al., 2008; Moore et al., 2010; Tourigny et al., 2006). CSA was linked not only to sexual dating violence, but also to psychological and physical manifestations of violence in the context of early romantic relationships. Thus, sexual abuse sustained in childhood may have an overreaching effect on other interpersonal experiences in adolescent dating experiences that are not limited to the realm of sexual health.

As stated previously, most studies have focused solely on female samples, with little known information on adolescent male experiences. Moreover, few studies examining the link between CSA and teen dating violence have relied on a representative sample of youth. In the present study, bivariate analyses indicated an increase in psychological and physical dating victimization among CSA victims compared to non-victims. A closer look at prevalence rates across gender show that male CSA victims were as likely as female CSA victims to report psychological (51% and 48% respectively) and physical (32% and 26% respectively) dating victimization. This is of particular interest since gender differences are often observed in general samples of adolescent for these forms of dating violence, whereas the present results suggest the presence of gender parity among victims of CSA rather than a disparity. In addition, sexual revictimization represents another threat to CSA victims. Sexual dating victimization rates in this study were marginally higher for CSA-girls than CSA-boys, with roughly one in three compared to almost one in five respectively. Many underlying factors can influence disclosure of sexual victimization involving a romantic partner experienced by boys. For example, due to certain socialization and gender stereotypes, boys may interpret coercive behaviors as not abusive (Walker, Carey, Mohr, Stein, & Seedat, 2004).

In comparison with other adverse life events, CSA was found to be a particularly strong predictor of revictimization in adults (Ports et al., 2016). To this end, our second aim was to document the association between CSA and different forms of dating victimization while controlling for other traumas, such as childhood physical abuse and witnessing interparental violence (psychological or physical) or violence against someone else. Adverse childhood life events that predicted later dating victimization were identical for both girls and boys on all three forms of violence, except for sexual violence where exposure to psychological interparental violence was only significant for female victims of CSA. Whereas exposure to interparental violence was associated with each form of dating violence, exposure to interparental physical violence had no significant effect when controlling for other factors, which is discordant with past findings (Glass et al., 2003; Whitfield et al., 2003). This could be attributed to the fact that analyses considered exposure to psychological and physical violence distinctively. Yet both forms of exposure tend to co-occur with exposure to interparental psychological violence more prevalent, which may have contributed to diluting an existing small effect.

Except for witnessing violence against someone else for girls, inspection of odds ratios indicated that CSA increased the risk of experiencing all forms of dating violence more than any other trauma assessed. On average, odds ratios were considerably higher for CSA boys on all three forms of dating victimization compared to CSA girls, in particular for sexual victimization, with boys 3.4 times more likely to be revictimized sexually in the context of their dating relationships compared to 1.69 for girls. This is a key finding that is telling of adolescent male CSA victims’ experiences in their dating relationships and is consistent with past findings indicating that male victims are at risk for being sexually revictimized (Elliott, Mok, & Briere, 2004). Moreover, CSA was not only linked to sexual dating victimization, but also psychological and physical violence. The central question that emerges from such conclusions is what is it that is specific to CSA that makes this an additional contribution over and above other interpersonal traumas? Whereas the specific mechanisms involved in revictimization are still not well delineated, some authors argue that PTSD and chronic hyperarousal may be associated with a lower capacity to discriminate between false alarms and real signs of danger, eventually leading victims of CSA to ignore potential threats, which in turn may place them at risk for revictimization (Risser, Hetzel-Riggin, Thomsen, & McCanne, 2006). A sense of powerlessness directly linked to the CSA experienced can also hinder a sense of self-efficacy about one’s ability to escape from difficult relationships. Another possible explanation is that, as a result of CSA, victims develop an insecure attachment style (Wolfe, Wekerle, Reitzel-Jaffe, & Lefebvre, 1998) with accompanying feelings of distrust and fear of intimacy (DiLillo et al., 2001), which can hamper the emergence of healthy dating relationships. Furthermore, a history of maltreatment can influence how behaviors are interpreted, with victims perceiving their partners to have more negative verbal and physical behaviors towards them, which in turn can generate disagreements (Wolfe et al., 1998). This may relate to Siegel’s (2006) concept of dyadic splitting, which is characterized by radical and sudden changes in perceptions of one’s romantic partner, thus contributing to relational difficulties.

Albeit having several strengths, the present study has certain limitations that must be considered. Firstly, although our data are generalizable to adolescent students in high school, the prevalence of dating violence may be higher in more vulnerable population, such as youth in child protective services. Furthermore, the present study was limited to individual accounts of dating victimization experiences within a relationship. Future studies should consider a dyadic perspective, from both members of the couple, in order to obtain a more accurate assessment of dating violence dynamics. Including other contextual variables that have been found to contribute to victimization would also be of merit (e.g., alcohol, drugs, duration of CSA, severity of the abuse). While our study attempted to consider different forms of interpersonal traumas experienced in childhood, our measure was limited and did not include experiences of neglect. Since not all CSA victims are revictimized, future research would gain in exploring and testing specific models that include mediating variables, such as emotion regulation, to document possible pathways of resilience. That said, this study has several strengths, including a representative sample and gender specific analysis. It is one of the few studies to have a large sample of boys that enables to explore the link between CSA and dating violence. Another noteworthy addition is the comprehensive assessment of different forms of dating violence, including sexual violence, which is rarely considered.

Implications for Research and Practice

In regards to implications for prevention, findings substantiate the need for early intervention efforts since violence can manifest itself in youths’ first romantic experiences. Adolescence represents an important window of opportunity to inform youth about healthy ways of relating. Therefore, prevention programs should include components on communication skills between partners to better cope with disagreements and conflicts by offering them concrete resolution strategies and positive communication skills that youth can apply in their relationships. Considering that youth cite their friends as their most helpful sources of support (Sylaska & Edwards, 2014), and that peer support is associated with lower post-traumatic stress symptoms (Hébert et al., 2014a), intervention efforts should consider peer bystanders and offer them tools with which to support youth who are victims of dating violence. Programs should also aim to debunk common socialization stereotypes, in particular those targeting males (e.g., asking for help as a sign of weakness), to encourage boys to come forth and obtain the help that they need in a safe and non-judgmental environment. In fact, evidence suggests that CSA youth perceive themselves as less apt to seek help for themselves in the context of dating violence (Hébert, Van Camp, Lavoie, Blais, & Guerrier, 2014b), thus highlighting the relevance for such programs.

Evaluations of universal prevention programs suggest they might not succeed in reducing the incidence of revictimization in CSA youth (Gidcyz, Rich, Orchowski, King, & Miller, 2006; Rothman & Silverman, 2007). Hence, CSA victims could benefit from more tailored and intensive programs that are adapted to their needs. Future research evaluating the outcomes of prevention strategies should assess CSA as a potential moderator variable. Programs that include components where youth can practice applying resistance strategies as well as offering support groups to at-risk youth also could be promising (Kerig, Volz, Moeddel, & Cuellar, 2010; Noll & Grych, 2011). Due to the reoccurring nature of victimization, education and prevention efforts starting in early childhood are also needed. An ecological framework seems particularly well suited for the development of prevention efforts to reduce the risk of revictimization among CSA victims and, ultimately, to stop sexual abuse before it occurs. A comprehensive approach targeting multiple levels of the social ecology (i.e., individual, relational, community and societal) needs to be considered. On the individual level, education on sexual abuse starting as early as preschool has shown promising results (Pitts, 2015). To achieve best results, these efforts should also target parents to optimize impact of awareness and skill-based programs (Hébert, Daigneault, Langevin, & Jud, in press). Training sessions for educators, professionals and community service providers working with children can also affect change on a broader community level. Media and public health campaigns specifically addressing child sexual abuse are also required to reach the general population and influence societal norms regarding abuse. In addition, central to the improvement of aiding victims is building the capacity of health care settings to better respond to specific needs of CSA youth victims. Policy implications should aim to support better service delivery for youth, including those male victims who are less likely to disclose and seek services. To prevent revictimization, continuous efforts must be made to build upon best practices by targeting not only symptoms associated with CSA but also the specific risk factors associated with dating violence.

Clinical treatments for sexually abused children can also gain from integrating educational components to reduce the risk of revictimization including skill-building exercises where children develop their capacity to identify risky situations and how to react to them accordingly. Activities such as role-playing scenarios can be used so that children gain confidence in their ability to properly assess a situation and learn how to say no in situations where they feel uncomfortable (Simoneau, Daignault, & Hébert, 2011). An emphasis should also be placed on developing and encouraging help-seeking behaviors and establishing a safety network comprised of adults in whom they trust. With adolescent clienteles, treatment should take into consideration the strong emotions generated by romantic relationships and accompanying sexual intimacy, which can be especially challenging for CSA victims. Therefore, interventions should address sexuality and intimacy during adolescence, including self-assertion regarding sexual needs. A particular emphasis should be placed on building healthy romantic relationship competencies (conflict resolution, affect regulation in situations of conflict) based on trust and positive communication. In this context, trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy strategies could contribute to reducing abuse stigmatization since they center on skill building (e.g., relaxation, affect modulation, coping mechanisms, mindfulness). This can positively influence how social information is interpreted and strengthen social competencies as a whole, which can then be applied in the context of CSA victims’ romantic experiences.

In conclusion, the present study supports previous evidence that there is a clear association between a history of CSA and dating victimization and confirms that this link is present for both genders. Therefore, a particular focus also needs to be placed on boys’ experiences of victimization following CSA and how they navigate their first romantic relationships to better understand the epidemiology of dating violence as a whole. Further research is needed to determine the strategies that are effective in reducing exposure to dating violence among adolescent boys and girls. Prevention efforts and services must consider the specific challenges and obstacles faced by both genders in order to reduce risk of revictimization and increase victims’ capacity to seek help.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the teenagers who participated in the study as well as the school personnel involved. This research was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research awarded to Martine Hébert (CIHR # 103944).

References

- Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Bremner JD, Walker JD, Whitfield CH, Perry BD, Dube SR, Giles WH. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2006;256(3):174–186. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afifi TO, MacMillan H, Cox BJ, Asmundson GJ, Stein MB, Sareen J. Mental health correlates of intimate partner violence in marital relationships in a nationally representative sample of males and females. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2009;24(8):1398–1417. doi: 10.1177/0886260508322192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banyard VL, Arnold S, Smith J. Childhood sexual abuse and dating experiences of undergraduate women. Child Maltreatment. 2000;5(1):39–48. doi: 10.1177/1077559500005001005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatta MP, Jefferis E, Kavadas A, Alemagno SA, Shaffer-King P. Suicidal behaviors among adolescents in juvenile detention: Role of adverse life experiences. PloS One. 2014;9(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD, Bolus R, Mayer EA. Psychometric properties of the early trauma inventory–self report. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2007;195(3):211–218. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000243824.84651.6c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Knoble NB, Shortt JW, Kim HK. # 4 A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse. 2012;3(2):1–27. doi: 10.1891/1946-6560.3.2.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan KL, Yan E, Brownridge DA, Tiwari A, Fong DY. Childhood sexual abuse associated with dating partner violence and suicidal ideation in a representative household sample in Hong Kong. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011;26(9):1763–1784. doi: 10.1177/0886260510372943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coid J, Petruckevitch A, Feder G, Chung WS, Richardson J, Moorey S. Relation between childhood sexual and physical abuse and risk of revictimisation in women: A cross-sectional survey. The Lancet. 2001;358(9280):450–454. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05622-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyr M, McDuff P, Wright J. Prevalence and predictors of dating violence among adolescent female victims of child sexual abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21(8):1000–1017. doi: 10.1177/0886260506290201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daigneault I, Hébert M, McDuff P. Men’s and women’s childhood sexual abuse and victimization in adult partner relationships: A study of risk factors. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2009;33(9):638–647. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiLillo D, Giuffre D, Tremblay GC, Peterson L. A closer look at the nature of intimate partner violence reported by women with a history of child sexual abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2001;16(2):116–132. doi: 10.1177/088626001016002002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DM, Mok DS, Briere J. Adult sexual assault: Prevalence, symptomatology, and sex differences in the general population. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2004;17(3):203–211. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000029263.11104.23. 0894-9867/04/0600-0203/1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feiring C, Cleland C. Childhood sexual abuse and abuse-specific attributions of blame over 6 years following discovery. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2007;31(11–12):1169–1186. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.03.020. doi:10.1016=j.chiabu.2007.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feiring C, Simon VA, Cleland CM, Barrett EP. Potential pathways from stigmatization and externalizing behavior to anger and dating aggression in sexually abused youth. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2013;42(3):309–322. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.736083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-González L, Wekerle C, Goldstein AL. Measuring adolescent dating violence: Development of conflict in adolescent dating relationships inventory (CADRI) short form. Advances in Adolescent Mental Health. 2012;11(1):35–54. doi: 10.5172/jamh.2012.2280. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Browne A. The traumatic impact of child sexual abuse: A conceptualization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1985;55(4):530–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1985.tb02703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Hotaling G, Lewis IA, Smith C. Sexual abuse in a national survey of adult men and women: Prevalence, characteristics, and risk factors. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1990;14(1):19–28. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(90)90077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Reyes HLM. Dating abuse: Prevalence, consequences, and predictors. In: Levesque RJR, editor. Encyclopedia of Adolescence. New York, NY: Springer Publishers; 2011. pp. 602–615. [Google Scholar]

- Gagné MH, Lavoie F, Hébert M. Victimization during childhood and revictimization in dating relationships in adolescent girls. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29(10):1155–1172. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gidycz CA, Rich CL, Orchowski L, King C, Miller AK. The evaluation of a sexual assault self-Defense and risk-reduction program for college women: A prospective study. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2006;30(2):173–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2006.00280.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glass N, Fredland N, Campbell J, Yonas M, Sharps P, Kub J. Adolescent dating violence: Prevalence, risk factors, health outcomes, and implications for clinical practice. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing. 2003;32(2):227–238. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.5.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grauerholz L. An ecological approach to understanding sexual revictimization: Linking personal, interpersonal, and sociocultural factors and processes. Child Maltreatment. 2000;5(1):5–17. doi: 10.1177/107755950000500100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamby S, Finkelhor D, Turner H. Teen dating violence: Co-occurrence with other victimizations in the national survey of children's exposure to violence (NatSCEV) Psychology of Violence. 2012;2(2):111–124. doi: 10.1037/a0027191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hébert M, Daigneault I, Langevin R, Jud A. L’agression sexuelle envers les enfants et les adolescents. In: Hébert Dans M, Fernet M, Blais M., editors. Enjeux du développement sexuel chez l'enfant et l'adolescent. Paris, France: De Boeck; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Hébert M, Daigneault I, Van Camp T. Agression sexuelle et risque de revictimisation à l'adolescence: Modèles conceptuels et défis liés à la prévention. In: Hébert M, Cyr M, Tourigny M, editors. L’agression sexuelle envers les enfants. Tome II. Ste-Foy, QC: Presses de l’Université du Québec; 2012. pp. 171–223. [Google Scholar]

- Hébert M, Lavoie F, Vitaro F, McDuff P, Tremblay RE. Association of child sexual abuse and dating victimization with mental health disorder in a sample of adolescent girls. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2008;21(2):181–189. doi: 10.1002/jts.20314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hébert M, Lavoie F, Blais M. Post Traumatic Stress Disorder/PTSD in adolescent victims of sexual abuse: resilience and social support as protection factors. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva [Science and Public Health] 2014a;19(3):685–694. doi: 10.1590/1413-81232014193.15972013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hébert M, Van Camp T, Lavoie F, Blais M, Guerrier M. Understanding the hesitancy to disclose teen dating violence: Correlates of self-efficacy to deal with teen dating violence. Temida. 2014b;17(4):43–64. doi: 10.2298/TEM1404043H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines DA. Predictors of sexual coercion against women and men: A multilevel, multinational study of university students. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2007;36(3):403–422. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9141-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerig PK, Volz AR, Moeddel MA, Cuellar RE. Implementing dating violence prevention programs with flexibility, fidelity, and sensitivity to diversity: Lessons learned from expect respect. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2010;19(6):661–680. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2010.502079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Abbey A, Campbell R, Cook S, Norris J, Testa M, … White J. Revising the SES: A collaborative process to improve assessment of sexual aggression and victimization. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2007;31(4):357–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00385.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Gidycz CA. Sexual experiences survey: Reliability and validity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53(3):422–423. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.53.3.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Oros CJ. Sexual Experiences Survey: A research instrument investigating sexual aggression and victimization. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1982;50(3):455–457. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.50.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMillan HL, Fleming JE, Streiner DL, Lin E, Boyle MH, Jamieson E, … Beardslee WR. Childhood abuse and lifetime psychopathology in a community sample. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2014;158(11):1878–1883. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin G, Bergen HA, Richardson AS, Roeger L, Allison S. Sexual abuse and suicidality: Gender differences in a large community sample of adolescents. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2004;28(5):491–503. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore TL, Long PJ. Child sexual abuse and revictimization in the form of adult sexual abuse, adult physical abuse, and adult psychological maltreatment. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2000;15(5):489–502. doi: 10.1177/088626000015005003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore TL, Long PJ. The role of childhood sexual abuse sequelae in the sexual revictimization of women: An empirical review and theoretical reformulation. Clinical Psychology Review. 2003;23(4):537–571. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(02)00203-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore EE, Romaniuk H, Olsson CA, Jayasinghe Y, Carlin JB, Patton GC. The prevalence of childhood sexual abuse and adolescent unwanted sexual contact among boys and girls living in Victoria, Australia. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2010;34(5):379–385. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noll JG, Grych JH. Read-react-respond: An integrative model for understanding sexual revictimization. Psychology of Violence. 2011;1(3):202–215. doi: 10.1037/a0023962. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell L, Stueve A, Myint-U A, Duran R, Agronick G, Wilson-Simmons R. Middle school aggression and subsequent intimate partner physical violence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006;35(5):693–703. doi: 10.1007/s10964-006-9086-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pica LA, Traoré I, Bernèche F, Laprise P, Cazale L, Camirand H, … Plante N. L’Enquête québécoise sur la santé des jeunes du secondaire 2010-2011. Le visage des jeunes d’aujourd’hui: Leur santé physique et leurs habitudes de vie, Tome 1. Québec, QC: Institut de la statistique du Québec; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pitts C. Child sexual abuse prevention programs for pre-schoolers: A synthesis of current evidence. Sydney, AU: Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ports KA, Ford DC, Merrick MT. Adverse childhood experiences and sexual victimization in adulthood. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2016;51:313–322. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao JNK, Scott AJ. The analysis of categorical data from complex sample surveys: Chi-squared tests for goodness of fit and independence in two-way tables. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1981;76(374):221–230. doi: 10.2307/2287815. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rao JNK, Scott AJ. On chi-squared tests for multiway contingency tables with cell proportions estimated from survey data. The Annals of Statistics. 1984;12(1):46–60. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2241033. [Google Scholar]

- Risser HJ, Hetzel-Riggin MD, Thomsen CJ, McCanne TR8. PTSD as a mediator of sexual revictimization: The role of reexperiencing, avoidance, and arousal symptoms. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2006;19(5):687–698. doi: 10.1002/jts.20156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman E, Silverman J. The effect of a college sexual assault prevention program on first-year students' victimization rates. Journal of American College Health. 2007;55(5):283–290. doi: 10.3200/JACH.55.5.283-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey RC, Zucosky H, Febres J, Brasfield H, Stuart GL. Males’ reactions to participating in research on dating violence victimization and childhood abuse. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2013;22(4):348–364. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2013.775987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel JP. Dyadic splitting in partner relational disorders. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20(3):418–422. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.3.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonelli CJ, Mullis T, Elliott AN, Pierce TW. Abuse by siblings and subsequent experiences of violence within the dating relationship. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2002;17(2):103–121. doi: 10.1177/0886260502017002001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simoneau AC, Daignault I, Hébert M. La thérapie cognitivo-comportementale axée sur le trauma. In: Hébert M, Cyr M, Tourigny M, editors. L’agression sexuelle envers les enfants. Tome I. Ste-Foy, QC: Presses de l’Université du Québec; 2011. pp. 363–398. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Stoltenborgh M, van IJzendoorn MH, Euser EM, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ. A global perspective on child sexual abuse: Meta-analysis of prevalence around the world. Child Maltreatment. 2011;16(2):79–101. doi: 10.1177/1077559511403920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised conflict tactics scales (CTS2) development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17(3):283–316. doi: 10.1177/019251396017003001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sylaska KM, Edwards KM. Disclosure of intimate partner violence to informal social support network members: A review of the literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2014;15(1):3–21. doi: 10.1177/1524838013496335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourigny M, Lavoie F, Vézina J, Pelletier V. La violence subie par des adolescentes dans leurs fréquentations amoureuses: Incidence et facteurs associés. Revue de Psychoéducation. 2006;35(2):323–354. [Google Scholar]

- Tourigny M, Hébert M, Joly J, Cyr M, Baril K. Prevalence and co-occurrence of violence against children in the Quebec population. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2008;32(4):331–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2008.00250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vagi KJ, Olsen EOM, Basile KC, Vivolo-Kantor AM. Teen dating violence (physical and sexual) among US high school students: Findings from the 2013 national youth risk behavior survey. Journal of the American Medical Association Pediatrics. 2015;169(5):474–482. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker JL, Carey PD, Mohr N, Stein DJ, Seedat S. Gender differences in the prevalence of childhood sexual abuse and in the development of pediatric PTSD. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2004;7(2):111–121. doi: 10.1007/s00737-003-0039-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wekerle C, Wolfe DA. Child maltreatment. In: Mash EJ, Russell RA, editors. Child Psychopathology. 2. New York, NY: Guilford; 2003. pp. 632–684. [Google Scholar]

- Wekerle C, Wolfe DA, Hawkins D, Pittman AL, Glickman A, Lovald BE. Childhood maltreatment, posttraumatic stress symptomatology, and adolescent dating violence: Considering the value of adolescent perceptions of abuse and a trauma mediational model. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13(04):847–871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield CL, Anda RF, Dube SR, Felitti VJ. Violent childhood experiences and the risk of intimate partner violence in adults: Assessment in a large health maintenance organization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2003;18(2):166–185. doi: 10.1177/0886260502238733. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe DA, Wekerle C. Pathways to violence in teen dating relationships. In: Cicchetti D, Toth SL, editors. Developmental Perspectives on Trauma: Theory, Research, and Intervention. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press; 1997. pp. 315–341. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe DA, Scott K, Reitzel-Jaffe D, Wekerle C, Grasley C, Straatman AL. Development and validation of the conflict in adolescent dating relationships inventory. Psychological Assessment. 2001;13(2):277–293. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.13.2.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe DA, Wekerle C, Reitzel-Jaffe D, Lefebvre L. Factors associated with abusive relationships among maltreated and nonmaltreated youth. Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10(01):61–85. doi: 10.1017/S0954579498001345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolitzky-Taylor KB, Ruggiero KJ, Danielson CK, Resnick HS, Hanson RF, Smith DW, … Kilpatrick DG. Prevalence and correlates of dating violence in a national sample of adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescence Psychiatry. 2008;47(7):755–762. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318172ef5f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization and the International Society for Child Abuse and Neglect. Preventing childhood maltreatment: A guide to taking action and generating evidence. Retrieved July 7, 2015 from http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2006/9241594365eng.pdf.