Abstract

Background

There is growing interest in coordinating care for high-risk patients through care management programs despite inconsistent results on cost reduction. Early evidence suggests patient-centered benefits, but we know little about how participants engage with the programs and what aspects they value.

Objective

To explore care management program participants’ awareness and perceived utility of program offerings.

Design

Cross-sectional telephone survey administered December 2015–January 2016.

Participants

Patients enrolled in a Boston-area primary care-based care management program.

Main measures

Our main outcome was the number of topics in which patients reported having “very helpful” interactions with their care team in the past year. We analyzed awareness of one’s care manager as an intermediate outcome, and then as a primary predictor of the main outcome, along with patient demographics, years in the program, attitudes, and worries as secondary predictors.

Key results

The survey response rate was 45.8% (n = 1220); non-respondents were similar to respondents. More respondents reported worrying about family (72.8%) or financial issues (52.5%) than about their own health (41.6%). Seventy-four percent reported care manager awareness, particularly women (OR 1.33, 95% CI 1.01–1.77) and those with more years in the program (OR 1.16, 95% CI 1.03–1.30). While interaction rates ranged from 19.8% to 72.4% across topics, 81.3% rated at least one interaction as very helpful. Those who were aware of their care manager reported very helpful interactions on more topics (OR 2.77, 95% CI 2.15–3.56), as did women (OR 1.25, 95% CI 1.00–1.55), younger respondents (OR 0.98 for older age, 95% CI 0.97–0.99), and those with higher risk scores (OR 1.04, 95% CI 1.02–1.06), preference for deferring treatment decisions to doctors (OR 2.00, 95% CI 1.60–2.50), and reported control over their health (OR 1.67, 95% CI 1.33–2.10).

Conclusions

High-risk patients reported helpful interactions with their care team around medical and social determinants of health, particularly those who knew their care manager. Promoting care manager awareness may help participants make better use of the program.

KEY WORDS: high-risk care management, high cost patients, patient-centered care, population health management

INTRODUCTION

As provider organizations take on greater financial risk for patients under value-based payment contracts, there is growing focus on the highest risk patients who incur an outsized portion of health care costs. Care management programs have emerged as one strategy to reduce health care costs and utilization for these patients—in particular, through practice-based programs in which care managers embedded in primary care or other clinical sites assist panels of high-risk patients in managing their medical conditions and related psychosocial problems.1 , 2 These programs are predicated on trusting relationships between patients and their care teams to help them navigate complex medical and social issues.3 , 4 While the programs have shown variable success at cost reduction,1 , 5 – 7 there is limited but growing evidence of patient benefits—such as satisfaction, quality of life, and perceived care integration—that are worthwhile and perhaps more realistic outcomes of such efforts.1 , 8 – 11 By better understanding how patients engage with care management programs and what they value in these interactions—the mechanisms through which programs might improve cost and quality outcomes—we may come closer to achieving both financial and patient-centered goals.12

Therefore, we surveyed patients participating in the Partners HealthCare care management program, a primary care-based, delivery system-operated program and one of the few that have demonstrated reduced costs and utilization,8 , 13 – 15 to understand patient perspectives on high-risk care management. We explored their attitudes about their health and how much they worried about health, financial, and family issues. We then investigated how many of them were able to identify the presence of a care manager and measured the topic and perceived helpfulness of the interactions they reported having with their care teams. We hypothesized that patients who identified the presence of a care manager were more likely to report helpful interactions with their care team around medical and social determinants of health.

METHODS

Telephone-based surveys of patients enrolled in the Partners HealthCare care management program were conducted by an independent survey research firm between December 7, 2015 and January 26, 2016.

Study Population

We used a stratified random sample of adult Medicare Pioneer Accountable Care Organization, Medicaid, and commercial plan beneficiaries under risk contracts who had been enrolled in the program for at least 6 months prior to survey administration. Program enrollees are 18 years old or greater and are chosen using a claims-based algorithm combined with clinician review.16

Survey Instrument

The 15-minute survey addressed the respondent’s awareness of a care manager; health attitudes; worry about health, family, and financial issues; and recollection and perception of interactions with their care team.

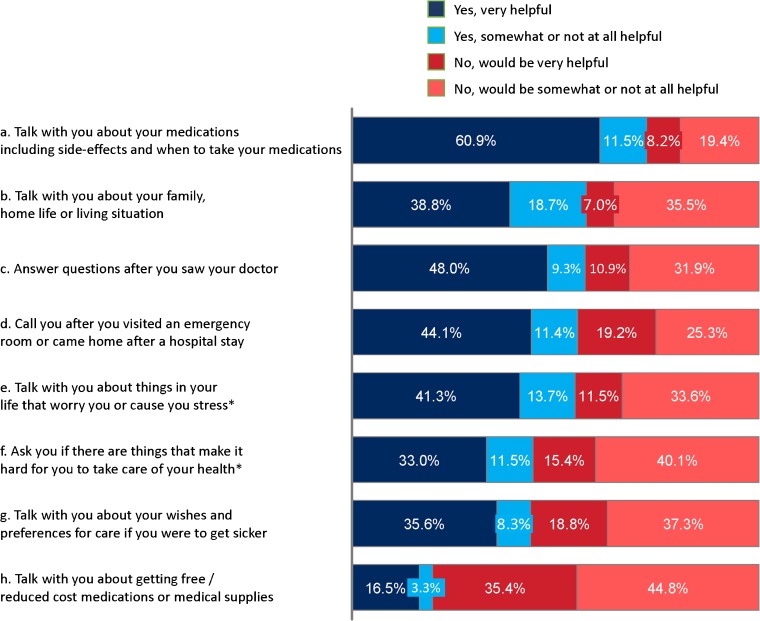

Patient awareness of a care manager was based on a survey item that asked respondents if there was an individual within their primary care practice who met the functional description of this role. This item, which is used as a quality metric within Partners HealthCare, was internally validated in a previous iteration of the survey by asking respondents to name the individual. We measured preference to leave treatment decisions to one’s doctors, perception of control over one’s own health, and level of worry about issues including health as well as housing, bills, and caring for family members.17 We used open-ended responses from the previous survey to delineate eight topics of interactions that patients might value having with their care team (Fig. 2). The wording for two of these items was adapted from Massachusetts Health Quality Partners (MHQP) and Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) surveys. For each item, the respondent was asked if anyone in his/her primary care doctor’s office had done the stated task. If the answer was yes, he/she was asked how helpful it was. If the answer was no, he/she was asked how helpful it might be.

Fig. 2.

Frequency and Reported Helpfulness of Interactions. For each of the items, the respondent was asked if anyone in his or her primary care doctor’s office had done the stated task in the last 12 months. If the answer was yes, he or she was asked how helpful it was. If the answer was no, he/she was asked how helpful it might be in the future. We included “do not know” responses as “No, would be somewhat or not at all helpful.” We did not include “refused” responses; total respondents for each sub-question ranged from 1174 to 1181. *Adapted from Massachusetts Health Quality Partners (MHQP) and Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) surveys

Survey Distribution

We called 3936 potential respondents between December 7, 2015 and January 26, 2016. Six call attempts were made for each individual to maximize sample size. Surveys were conducted in English and in Spanish.

Measures

We determined baseline characteristics including the 2016 Impact Pro Risk Score (calculated using January–December 2015 claims) as well as area-level poverty (percent of individuals living in the subject’s census tract with incomes below the federal poverty level, among those for whom data were available) and area-level education (percent of individuals living in the subject’s census tract who attended any amount of college, among those for whom data were available) from the 2008–2012 American Community Survey.18

We dichotomized each type of worry as present (“a great deal” or “a fair amount”) or absent (“only a little” or “not at all”). Caregiver worry was defined as reported worrying about “caring for your family” or “the health of a close family member,” while financial worry was defined as reported worrying about “paying your bills,” “running out of food or affording food,” or “maintaining your income or job.” We reported health control (defined as “strongly agree” that “I have control over my health”) and, separately, preference for doctors making treatment decisions (defined as “strongly agree” that “I prefer to leave all treatment decisions to my doctors”). Care manager awareness was defined as answering “yes” to the question: “Is there someone who works with your primary care doctor who helps you with your medical care?”

Data Analysis

We calculated descriptive statistics of respondents’ demographic and other baseline characteristics; health attitudes; health, financial, and caregiver worries; awareness of their care manager; and the receipt and perceived or anticipated helpfulness of various topics of interactions with the care team. Confidence intervals were calculated using standard error. To evaluate differences between respondents and non-respondents, we used chi-square tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables.

We first analyzed care manager awareness as an intermediate outcome. We then examined awareness of the care manager as a primary predictor and time in the program, health worry, financial worry, and caregiver worry as secondary predictors of our main outcome: the number of issues about which patients reported having “very helpful” interactions with their care team (range 0–8). For the binary outcome assessing awareness of the care manager, we performed bivariate analyses using the t-test for continuous variables and the chi-square test for dichotomized variables. For the ordinal outcome measuring the number of very helpful interactions, we used univariate ordinal logistic regression models.

Models

We built a logistic regression model to determine the adjusted effects on care manager awareness of sex, age, insurer, risk score, preference to defer health decisions, health control, health, financial, and caregiver worry, and time in the program. We then created an ordinal logistic regression model to examine the effect of care manager awareness on the number of very helpful interaction topics while controlling for gender, age, insurance type, risk score, preference to defer health decisions, health control, health, financial, and caregiver worry, and time in the program.

All analyses were performed using STATA 13.0 for Windows (STATA Corp., College Station, TX). All reported p values are two-tailed, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The primary purpose of the Partners HealthCare care management program patient survey was to improve care quality; secondary research use of the data was approved by the Partners Institutional Review Board. The study had no external funding source.

RESULTS

We achieved a 45.8% response rate based on the American Association for Public Opinion Research RR3 definition (n = 1220);19 38 patients who were discharged from the program prior to the beginning of the survey period were subsequently excluded from this analysis (n = 1182). Non-respondents did not differ significantly from respondents by sex, age, race, area-level poverty and education, or risk score (Table 1). Eight percent of analyzed surveys were completed by proxies (94, 8.0%).

Table 1.

Respondent and Non-Respondent Characteristics

| Characteristic | Respondents (n = 1182) | Non-respondents (n = 2766)a | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 60.8% (719)b | 61.7% (1707)b | 0.43 |

| Age, years (95% CI) | 70.7 (69.9–71.5) | 70.0 (69.5–70.6)b | 0.20 |

| Race (Medicare only) | 0.06 | ||

| White | 89.8% (696)c | 88.3% (1498) | |

| Black | 7.4% (57) | 6.8% (116) | |

| Other | 2.8% (22) | 4.9% (83)d | |

| Area-level poverty, mean % below federal poverty level (95% CI) | 9.5% (8.9–10.0)e | 9.9% (9.5–10.3)f | 0.25 |

| Area-level education, mean % who attended some college (95% CI) | 65.8% (64.7–66.8)e | 65.2% (64.5–65.8)f | 0.32 |

| Insurer | 0.02 | ||

| Medicare ACO | 66.0% (780) | 61.9% (1713) | |

| Commercial | 28.2% (333) | 32.5% (898) | |

| Medicaid | 5.8% (69) | 5.0% (139)d | |

| Impact Pro Risk Score (95% CI) | 7.8 (7.4–8.2)g | 7.5 (7.3–7.8)h | 0.25 |

| Years in program (95% CI) | 2.5 (2.4–2.6) | 3.0 (2.7–3.2)i | 0.04 |

| Reported awareness of care manager | 73.7% (871) | N/A | |

| Preference to defer decisions to doctors | 39.3% (464) | N/A | |

| Health control | 64.2% (749)d | N/A | |

| Health worry | 41.6% (492) | N/A | |

| Caregiver worry | 72.8% (861) | N/A | |

| Financial worry | 52.5% (621) | N/A |

95% CI, 95% confidence interval; bold if statistically significant

ACO, accountable care organization. aSome non-respondents were excluded from the response rate calculation based on AAPOR’s RR3 criteria. The nonrespondent analysis includes 50 individuals who were removed from the sample for administrative reasons. Missing data b: 9, c: 5, d: 16, e: 108, f: 274, g: 90, h: 361, i: 11

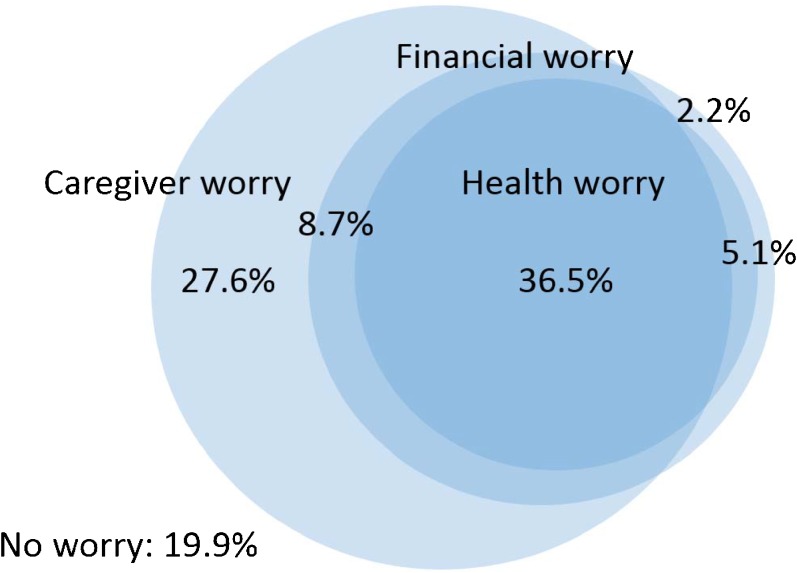

Demographics, Attitudes, and Worries

Respondents were predominantly female, white, and enrolled in Medicare (Table 1). Their ages ranged from 25 to 104 years old. Over one-third (39.3%) of respondents said that they prefer to leave all treatment decisions to their doctors, while 64.2% reported feeling in control of their health. More respondents reported worrying about a family member’s health or taking care of family (72.8%) or about financial issues such as bills, maintaining income, or affording food (52.5%) than about their own health (41.6%). No respondents reported worrying exclusively about their own health (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Patient report of health, caregiver, and financial worry. Venn diagram shows patient report of health worry, financial worry (paying bills, affording food, or maintaining income), and caregiver worry (caring for family or family member’s health)

Care Manager Awareness

Nearly three quarters (73.7%) of patients reported someone fitting the description of a care manager (Table 2). Women (1.33; 95% CI 1.01–1.75) and those with more time in the program (1.16 per year; 95% CI 1.03–1.30) had higher odds of identifying a care manager in adjusted analyses. In bivariate analyses, those who reported health and caregiver worry also had higher odds of identifying a care manager, but these effects were not significant in the multivariable model.

Table 2.

Patient Characteristics Associated with Reported Awareness of Care Manager

| Patient characteristic | Awareness of care manager | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 871) | No/Do not know (n = 311) | |||

| Female | 62.0% (540) | 57.6% (179) | 1.20 (0.93–1.56) | 1.33 (1.01–1.77) |

| Male | 38.0% (331) | 42.4% (132) | Ref | Ref |

| Age, years (95% CI) | 70.3 (69.5–71.2) | 71.7 (70.2–73.3) | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) | 1.00 (0.99–1.02) |

| Insurer | ||||

| Medicare | 64.8% (564) | 69.5% (216) | Ref | Ref |

| Commercial | 28.7% (250) | 26.7% (83) | 1.15 (0.86–1.55) | 1.30 (0.88–1.91) |

| Medicaid | 6.5% (57) | 3.9% (12) | 1.82 (0.96–3.46) | 1.97 (0.91–4.25) |

| Impact Pro Risk Score (95% CI) | 7.9 (7.4–8.3) | 7.5 (6.8–8.3) | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 1.01 (0.99–1.04) |

| Years in program (95% CI) | 2.5 (2.5–2.6) | 2.4 (2.2–2.5) | 1.12 (1.01–1.25) | 1.16 (1.03–1.30) |

| Preference to defer decisions | 40.4% (352) | 36.01% (112) | 1.21 (0.92–1.58) | 1.31 (0.97–1.75) |

| Health control | 64.77% (557) | 62.75% (192) | 1.09 (0.83–1.43) | 1.05 (0.79–1.41) |

| Health worry | 43.6% (380) | 36.0% (112) | 1.38 (1.05–1.80) | 1.47 (0.93–2.33) |

| Caregiver worry | 74.5% (649) | 68.2% (212) | 1.37 (1.03–1.81) | 1.26 (0.92–1.74) |

| Financial worry | 54.1% (471) | 48.2% (150) | 1.26 (0.98–1.64) | 0.85 (0.54–1.33) |

OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval. Bold if statistically significant

We built a regression model with the following covariates: sex, age, insurer, risk score, years in program, decision-making preference, health control, and health, caregiver, and financial worry

Interactions with Care Team

The percentage of respondents reporting a given topic of interaction in the previous year ranged from 19.8% to 72.4% (Fig. 2). Eighty-one percent (81.3%) reported at least one topic of “very helpful” interaction with their care team; respondents reported such interactions on an average of three out of eight possible topics. Patients who identified the presence of a care manager were more likely to recall interactions in each of the topics (data not shown) and had significantly greater odds (2.77; 95% CI 2.15–3.56) of reporting very helpful interactions across more topics when controlling for covariates (Table 3). Women, younger patients, and respondents with higher risk score as well as those who reported health control and preference to defer treatment decisions also had greater odds of reporting more of these interactions. In bivariate analysis, Medicaid patients had greater odds of reporting very helpful interactions, but this result was no longer significant in the multivariate model. In a secondary analysis, we found that this effect was explained by younger age and higher odds of financial and health worry among Medicaid patients compared to Medicare beneficiaries.

Table 3.

Effects of Patient Characteristics on Number of Reported “Very Helpful” Interactions

| Characteristic | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 1.18 (0.96–1.45) | 1.25 (1.00–1.55) |

| Age | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) |

| Insurer | ||

| Medicare | Ref | Ref |

| Commercial | 1.24 (0.99–1.55) | 1.03 (0.76–1.39) |

| Medicaid | 2.09 (1.33–3.27) | 1.28 (0.74–2.21) |

| Mean Impact Pro Risk Score | 1.04 (1.02–1.05) | 1.04 (1.02–1.06) |

| Years in program | 1.08 (1.00–1.17) | 1.09 (1.00–1.19) |

| Preference to defer decisions | 1.85 (1.51–2.28) | 2.00 (1.60–2.50) |

| Health control | 1.69 (1.37–2.08) | 1.67 (1.33–2.10) |

| Health worry | 1.59 (1.30–1.95) | 1.34 (0.94–1.91) |

| Caregiver worry | 1.43 (1.14–1.80) | 1.17 (0.91–1.51) |

| Financial worry | 1.52 (1.24–1.86) | 0.94 (0.66–1.34) |

| Reported awareness of care manager | 3.07 (2.43–3.88) | 2.77 (2.15–3.56) |

OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval. Bold if statistically significant

We built a regression model with reported awareness of the care manager as the primary predictor and the following covariates: sex, age, insurer, risk score, years in program, decision-making preference, health control, and health, caregiver, and financial worry

DISCUSSION

We found that patients in a high-risk care management program reported very helpful interactions with their care team around core program features such as post-hospitalization follow-up and addressing barriers to self-care, although there were some missed opportunities for engagement. Those who were aware of their care manager were more likely to report very helpful interactions with the care team across more topics.

Program participants were enrolled primarily on the basis of their medical cost and complexity, yet notably, no respondent worried exclusively about their own health and they were more likely to report worrying about family members or about financial issues. These findings substantiate previous studies showing that high cost patients tend to have greater unmet resource needs20 and lower socioeconomic status.21 – 25 These challenges, in turn, may make it more difficult for individuals to address health issues or navigate the health system.17 , 20 , 26 – 28 Responses to questions about worry may not only reflect health and socioeconomic realities but also the respondents’ propensity to worry, a trait that seems to be independent of anxiety and depression.29 Whatever the underlying cause, the marked prevalence of these worries emphasizes the need for care management programs to help patients address such issues. These findings also highlight the idea that patients’ priorities may not align with those perceived or focused on by their clinicians and that collaborative goal setting with patients may be an important strategy to improve outcomes.27

Awareness of the Care Manager

Most respondents reported that there was “someone who works with your primary care doctor who helps you with your medical care”—suggesting that they could identify the individual and found his or her role helpful. This question serves as an institution-wide quality metric—a marker of the relationship upon which the program is based—and the proportion responding yes rose by 10% from the previous year. In our survey, participants enrolled in the program for longer durations were more likely to answer “yes,” perhaps reflecting greater opportunity to become acquainted with their care managers; women were also more likely to identify a care manager.

Interactions

Previous work has found that patients in care management programs are 1.3 to 2.6 times more likely than non-enrollees to recall receiving education on topics such as diet, exercise, and medication administration; in most of the programs studied, the majority of participants recalled having such discussions and receiving help from their care teams, but it was not clear if they found them helpful.5 In our study, most patients reported at least one very helpful interaction and an average of three such interactions. Still, our findings suggest that there were missed opportunities for patient engagement around topics such as opportunities for lower cost medications or supplies. With the exception of follow-up after visiting the emergency department or hospital, which is contingent on having had such a visit in the past year, all eight interaction topics would be applicable to any high-risk patient.

These interactions represent the mechanisms by which care management programs might achieve improved quality and cost outcomes for patients.30 One of the distinguishing features of two care management programs showing early success was patient self-report of being taught how to take their medications.5 In a follow-up study, successful programs were more likely to feature (1) care managers who played the role of communication coordinator, (2) strong evidence-based patient education, (3) comprehensive medication management, and (4) attention to post-hospitalization transitions6—all topics that respondents in our study reported to be helpful.

Not surprisingly, those who reported awareness of their care manager were more likely to report helpful interactions with their teams: care managers likely play a role in these interactions, whether as leaders or facilitators. Patients with stronger connections to their care managers may have more of these important interactions, or conversely it may be that patients got to know their care managers through the interactions. A third factor—such as patient cognitive function—may explain both care manager awareness and recollection of helpful interactions.

Women were more likely to be aware of their care managers and to report more helpful interactions—in line with studies showing that female patients tend to seek out and use more health care services than men, including more medical visits, and report higher satisfaction with care.31 , 32 This may also reflect the positive impact of gender concordance in building relationships, given that approximately 95% of care managers in the Partners program are female. Younger patients and those with greater medical complexity were also more likely to report very helpful interactions across topics, perhaps reflecting greater need for these services. We also found that patients who reported control over their health as well as those who preferred to leave treatment decisions to their doctors had higher odds of reporting very helpful interactions across more topics. These associations might be mediated by factors such patients’ ability to express and advocate for their needs during an interaction or by patients’ trust in their doctors or in the health system. Interestingly, a previous study found that hospitalized patients who preferred to defer medical decisions had shorter lengths of stay and lower hospitalization costs.33

Finally, while our study was underpowered with respect to Medicaid enrollment, these patients were disproportionately likely to know their care manager and, in bivariate analysis, had statistically significant greater odds of reporting more helpful interactions, suggesting that these patients may particularly benefit from care management. This is particularly notable given the recent emergence of Medicaid Accountable Care Organization pilot programs in Massachusetts and elsewhere.

Implications

Though it is impossible to show causality in this study design, the association between care manager awareness and the number of very helpful interactions does support the hypothesis that an intervention that strengthens patients’ relationships with their care manager may help them make better use of the program. This finding is consistent with previous studies showing that successful care management programs are more likely to feature frequent face-to-face interactions between care managers and patients.6 An intervention such as an introductory video series might similarly help patients get to know their care managers and has since been employed at some program sites.34 In addition, our study suggests that patient attributes such as preference to defer treatment decisions or sense of health control may help to identify candidates who will most benefit from these resource-intensive programs.3

Limitations

These results should be interpreted in the context of the study’s limitations. The survey focused on the care management program of a single health system, albeit one that represents one of a few successful care management models and spans several care settings including two quarternary care hospitals and numerous community-based primary care sites and community health centers.8 , 13 , 15 Our response rate was somewhat low, though not unusually so for a patient survey in a high-risk population.35 Furthermore, we found nonsignificant differences between respondents and non-respondents across most demographic categories, suggesting limited non-response bias.36 Respondents were more likely than non-respondents to be Medicare beneficiaries and to have spent less time in the program, so our findings may disproportionately represent these groups.

Due to the cross-sectional design, we cannot make causal inferences about the associations that we observed. We assumed stability of responses about worries and health attitudes, though some aspects of worry such as food security may be dynamic in the course of a year. We used generic terminology to ask respondents if they were aware of their care manager because this role has differing titles across care management program sites; this may have biased our estimates in either direction. Respondents may have difficulty remembering interactions over the past year, so we may underestimate interaction rates; however, at most 5.4% of respondents answered “I do not know” to any of these questions. Finally, the hybrid claims and clinician-based patient selection methodology used in the Partners HealthCare care management program may skew our sample in favor of patients who are perceived as either engaged or having needs likely to be met by the program,16 limiting the generalizability of our study to programs with a similar selection approach. However, to our knowledge, most programs employ this approach, mitigating this limitation.37

Despite these limitations, this study robustly addresses the patient-centered outcomes of care management interventions that may serve as more proximal and meaningful outcomes of such programs than reductions in cost and utilization.

Conclusion

We found that respondents worried much more about financial and caregiver issues than about their own health, reinforcing the socioeconomic burdens felt by high-risk patients and the need for programs to address these issues. As with any intervention, it is important to ensure that care management programs provide patients with services that they themselves want and find to be useful. Most participants in our survey found interactions with the care team very helpful across several topics, particularly if they were aware of their care managers, suggesting that strengthening these relationships may improve the patient-centered outcomes that are meaningful and realistic goals of high-risk care management.

Contributors

We thank Maryann Vienneau (Partners Center for Population Health) and Jessica Moschella, MPH (Emerson Physician-Hospital Organization) for their work on the Partners HealthCare care management program and Tom Bodenheimer, MD, MPH (University of California, San Francisco), for his thoughtful review of our manuscript.

Funding

There was no financial or material support for the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Prior presentations

This work was presented at the 2017 Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting on April 21, 2017.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Berry-Millett R, Bodenheimer TS. Care management of patients with complex health care needs. Synth Proj Res Synth Rep. [PubMed]

- 2.Bodenheimer T, Berry-Millett R. Follow the money—controlling expenditures by improving care for patients needing costly services. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1521–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0907185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colbert J, Ganguli I. To Identify Patients For Care Management Interventions, Look Beyond Big Data. Health Affairs Blog. April 19, 2016. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2016/04/19/to-identify-patients-for-care-management-interventions-look-beyond-big-data/. Accessed April 4, 2017.

- 4.Nelson L. Lessons From Medicare’s Demonstration Projects on Disease Management and Care Coordination. Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peikes D, Chen A, Schore J, Brown R. Effects of care coordination on hospitalization, quality of care, and health care expenditures among Medicare beneficiaries: 15 randomized trials. JAMA. 2009;301:603–18. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown RS, Peikes D, Peterson G, Schore J, Razafindrakoto CM. Six features of Medicare coordinated care demonstration programs that cut hospital admissions of high-risk patients. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:1156–66. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zulman DM, Cee CP, Ezeji-Okoye SC, et al. Effect of an intensive outpatient program to augment primary care for high-need Veterans Affairs patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:166–175. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCall N, Cromwell J, Urato C. Evaluation of Medicare Care Management for High Cost Beneficiaries (CMHCB) Demonstration: Massachusetts General Hospital and Massachusetts General Physicians Organization (MGH). 2010. http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Reports/downloads/mccall_mgh_cmhcb_final_2010.pdf. Accessed November 14, 2016.

- 9.McWilliams JM, Landon BE, Chernew ME, Zaslavsky AM. Changes in patients’ experiences in Medicare accountable care organizations. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1715–1724. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1406552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McWilliams JM. Cost containment and the tale of care coordination. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2218–2220. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1610821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fryer AK, Friedberg MW, Thompson RW, Singer SJ. Achieving care integration from the patients’ perspective: results from a care management program. Healthc (Amst). 2016;4:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ganguli Ishani, Thompson Ryan W., Ferris Timothy G. What can five high cost patients teach us about healthcare spending? Healthcare. 2017;5(4):204–213. doi: 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2016.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Urato C, McCall N, Cromwell J, Lenfestey N, Smith K, Raeder D. Evaluation of the Extended Medicare Care Management for High Cost Beneficiaries (CMHCB) demonstration: Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH). Final report. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI International; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hong CS, Siegel AL, Ferris TG. Caring for High-Need, High-Cost Patients: What Makes for a Successful Care Management Program? The Commonwealth Fund, August 2014. [PubMed]

- 15.Hsu J., Price M., Vogeli C., Chernew M., Ferris T. ISQUA16-2413THE IMPACT OF NEW PAYMENT MODELS ON CARE DELIVERY: REDUCTIONS IN EMERGENCY CARE USE AMONG BENEFICIARIES IN A MEDICARE PIONEER ACO. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2016;28(suppl 1):27–27. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzw104.39. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vogeli C, Spirt J, Brand R, Hsu J, Mohta N, Hong C, Weil E, Ferris TG. Implementing a hybrid approach to select patients for care management: variations across practices. Am J Manag Care. 2016;22:358–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gelberg L, Gallagher TC, Andersen RM, Koegel P. Competing priorities as a barrier to medical care among homeless adults in Los Angeles. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:217–220. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.87.2.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Community Survey. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/data.html. Accessed April 4, 2017.

- 19.The American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. April 2015. https://www.aapor.org/AAPOR_Main/media/publications/Standard-Definitions2015_8theditionwithchanges_April2015_logo.pdf. Accessed January 23, 2017.

- 20.Berkowitz SA, Hulberg AC, Hong C, Stowell BJ, Tirozzi KJ, Traore CY, Atlas SJ. Addressing basic resource needs to improve primary care quality: a community collaboration programme. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25:164–72. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hunt KA, Weber EJ, Showstack JA, Colby DC, Callaham ML. Characteristics of frequent users of emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sutherland JM, Fisher ES, Skinner JS. Getting past denial—the high cost of health care in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1227–1330. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0907172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Health Policy Commission. 2013 Cost Trends Report. Boston, MA. 2013 http://www.mass.gov/anf/docs/hpc/2013-cost-trends-report-full-report.pdf. Accessed April 4, 2017.

- 24.Johnson TL, Rinehart DJ, Durfee J, et al. For many patients who use large amounts of health care services, the need is intense yet temporary. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34:1312–9. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ryan J, Abrams MK, Doty MM, Shah T, Schneider EC. How High-Need Patients Experience Health Care in the United States: Findings from the 2016 Commonwealth Fund Survey of High-Need Patients, The Commonwealth Fund, December 2016. [PubMed]

- 26.Schlossstein E, St. Clair P, Connell F. Referral keeping in homeless women. J Community Health. 1991;16:279–285. doi: 10.1007/BF01324513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zulman DM, Kerr EA, Hofer TP, Heisler M, Zikmund-Fisher BJ. Patient-provider concordance in the prioritization of health conditions among hypertensive diabetes patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;208-414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Mautner DB, Pang H, Brenner JC, Shea JA, Gross KS, Frasso R, Cannuscio CC. Generating hypotheses about care needs of high utilizers: lessons from patient interviews. Popul Health Manag. 2013;16(Suppl 1):S26–33. doi: 10.1089/pop.2013.0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meyer TJ, Miller ML, Metzger RL, Borkovec TD. Development and validation of the Penn State worry questionnaire. Behav Res Ther. 1990;28:487–95. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(90)90135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berkowitz SA, Hulberg AC, Standish S, et al. Addressing unmet basic resource needs as part of chronic cardiometabolic disease management. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:244–252. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bertakis KD, Azari R, Helms LJ, Callahan EJ, Robbins JA. Gender differences in the utilization of health care services. J Fam Pract. 2000;49:147–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bertakis KD. The influence of gender on the doctor-patient interaction. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;76:356–60. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tak HJ, Ruhnke GW, Meltzer DO. Association of patient preferences for participation in decision making with length of stay and costs among hospitalized patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1195–1205. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ganguli Ishani, Sikora Chrisanne, Nestor Briana, Sisodia Rachel Clark, Licurse Adam, Ferris Timothy G., Rao Sandhya. A Scalable Program for Customized Patient Education Videos. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2017;43(11):606–610. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjq.2017.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elliott MN, Zaslavsky AM, Goldstein E, et al. Effects of survey mode, patient mix, and nonresponse on CAHPS hospital survey scores. Health Serv Res. 2009;44:501–518. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00914.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davern M. Nonresponse rates are a problematic indicator of nonresponse bias in survey research. Health Serv Res. 2013;48:905–12. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hong CS, Hwang AS, Ferris TG. Finding a Match: How Successful Complex Care Programs Identify Patients. Issue Brief California HealthCare Foundation. http://www.chcf.org/~/media/MEDIA%20LIBRARY%20Files/PDF/PDF%20F/PDF%20FindingMatchComplexCare.pdf. Accessed July 14, 2017.