Abstract

Background:

Stray dogs are considered potential reservoirs for zoonotic diseases. Previous helminthic surveys in Iran, have accounted for mainly species of nematodes and cestodes, and rarely digeneans.

Methods:

We accessed 42 car-crashed stray dogs from the Farah Abad Region in the Mazandaran Province (North Iran) between Oct 2012 and Dec 2013, to be inspected for parasites. Helminths were collected from the intestine and they were morphologically studied.

Results:

We found five adult digeneans from the family Brachylaimidae, identified as Brachylaima sp. Worms were assigned to the genus based on the shape of the body, the position of genital pore, cirrus sac and testes, and the extension of the vitellarium. Absence of additional information on the developmental stages of the parasite precluded its specific identification. As the geographic distribution of species of Brachylaima is restricted to the Mediterranean region, we raise the hypothesis that dogs may become infected with parasites through the consumption of helicid snails when searching for food on the street.

Conclusion:

This is the second report of a species of Brachylaima in Iran and the third digenean species from stray dogs in the area. We want to raise the attention of researchers to helminthic surveys in potential zoonotic reservoirs like stray dogs.

Keywords: Stray dog, Zoonosis, Digenea, Brachylaima, Iran

Introduction

Stray dogs, Canis familiaris, in Iran are considered potential reservoirs for zoonotic diseases and a risk to public health (1, 2). The large population of stray dogs in Iran generates hygienic issues affecting the public perception of dogs and making policies for prevention and control of diseases difficult to accomplish (1). Over the last decade, a significant burden, i.e., >80%, of zoonotic species, mainly nematodes, and cestodes, have been reported in stray dogs in Iran, believed to become infected by consuming water, soil or food with helminth larvae (1-4). Interestingly, only one species of digeneans of the family Diplostomidae (Alaria alata), one of the family Heterophyidae (Ascocotyle sinoecum), and one of the Brachylaimidae (Brachylaima sp.) have been reported in these surveys (1, 5), highlighting the low prevalence of this group of helminths. Nevertheless, in other geographic regions, dogs have been found to harbour several species of digeneans, from which the families Echinostomatidae, Heterophyidae, Opisthorchiidae, and Paragonimidae have a major species representation (6). Therefore, the routinely parasitic surveys in zoonotic species, like stray dogs, should be considered as of primary importance.

The Mazandaran Province is located in the north of Iran and the southern coast of the Caspian Sea (Fig. 1). This is one of the most densely populated provinces in Iran and has a changing climate from mild to humid, with variable rates of rainfall throughout the year (7). In this study, we provide evidence on the occurrence of a digenean from the Brachylaimidae isolated from a stray dog in the Farah Abad region in the central part of the Mazandaran Province.

Fig. 1:

Map of Iran and collection site of the specimens of Brachylaima sp. from a stray dog. The Mazandaran province is colored in dark grey and the Farah Abad region is indicated by a black circle.

Materials and Methods

Between Oct 2012 and Dec 2013, 42 car-crashed stray dogs, Canis familiaris, were collected in the Mazandaran Province, Northern Iran. Animals were transported to the Laboratory at the School of Medicine in the Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences for necropsy.

The intestine of each animal was separated from the rest of the organs and inspected for parasites. Each intestinal content was filtered over a sieve of 180 μm and 250 μm meshes to collect helminths. Worms were isolated, washed with saline, flattened with a light pressure over the cover glass and fixed in lactophenol. Parasites were stained with carmine, dehydrated and cleared in xylene. Each specimen was mounted in slides with Canada balsam.

Morphometric analyses of stained specimens were performed on an Olympus BX41 microscope connected to an Olympus Dp12 Digital camera calibrated with an eyepiece micrometer. Drawings of each individual were done under an optical microscope with Camera Lucida.

Results

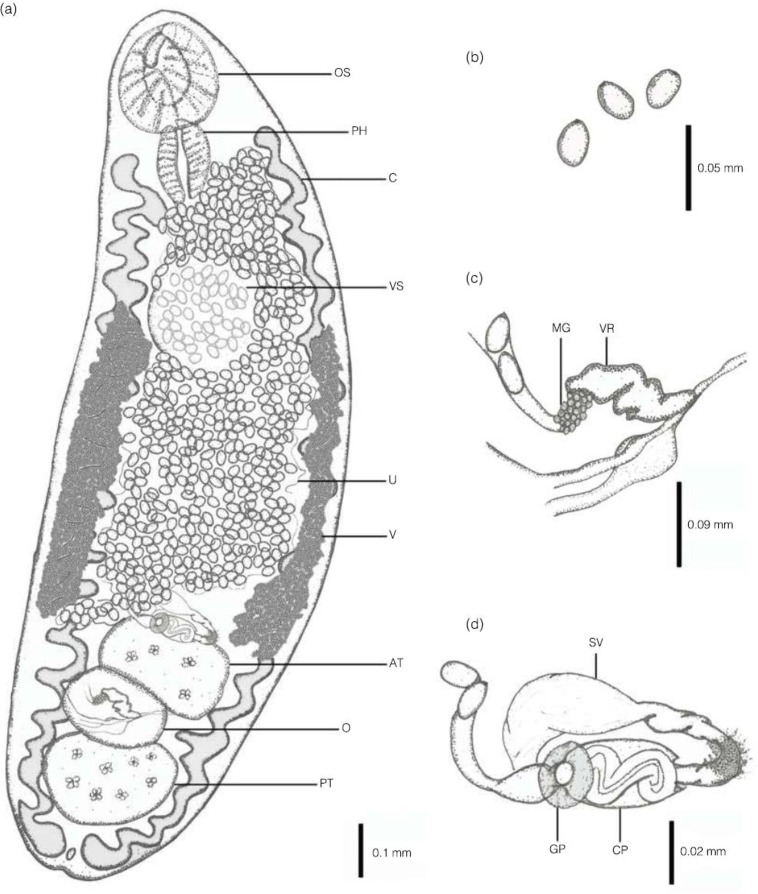

Five adult digeneans were collected from the intestine of 1 out of the 42 stray dogs surveyed in the Farah Abad district in the Mazandaran Province (Fig. 2). The specimens found were keyed down to the family Brachylaimidae and the genus Brachylaima based on the shape of the body, the position of the genital pore, cirrus sac, and testes, and the extension of the vitellarium (Fig. 2). All the material reported from this study is deposited in the Iranian National Parasitology Museum at the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Tehran, Iran (ID. 829/9.1393), and it is available upon request.

Fig. 2:

Brachylaima sp. from a stray dog, Canis familiaris. (a) Ventral view. (b) Detail of eggs. (c) Detail of female reproductive system. (d) Detail of male reproductive system. Scale bars are indicated for each image. Abbreviations: AT, Anterior testis; C, caeca; CP, Cirrus pouch; GP, Genital pore; MG, Mehlis’s gland; O, Ovary; OS, Oral sucker; PH, Pharynx; PT, posterior testis; SV, Seminal vesicle; U, Uterus; V, Vitelline follicles; VR, Vitel-line reservoir; VS, Ventral sucker

Morphological description

Observations and measurements based on 5 whole-mounted specimens. Measurements (length × width) are shown as the range, with the mean in parenthesis followed by the standard deviation, and are expressed in micrometers (Table 1, Fig. 2).

Table 1:

Measurements (in μm) of adult worms (n=5) of Brachylaima sp. isolated from a stray dog, Canis familiaris, in the Farah Abad region, Mazandaran Province (Iran)

| Variable | Mean±SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Worm body | |||

| Length | 2,214 ± 991.4 | 1,490 – 3,300 | |

| Width | 580.0 ± 109.5 | 500 – 700 | |

| Oral sucker | |||

| Length | 237.8 ± 20.3 | 223 – 260 | |

| Width | 196.8 ± 12.0 | 188 – 210 | |

| Ventral sucker | |||

| Length | 175.4 ± 25.2 | 157 – 203 | |

| Width | 155.6 ± 35.1 | 130 – 194 | |

| Pharynx | |||

| Length | 168.3 ± 32.7 | 109.7 – 182.9 | |

| Width | 109.7 ± 22.4 | 73.2 – 128.0 | |

| Anterior testis | |||

| Length | 206.8 ± 14.8 | 196 – 223 | |

| Width | 155.2 ± 31.8 | 132 – 190 | |

| Posterior testis | |||

| Length | 206.2 ± 56.4 | 165 – 268 | |

| Width | 194.2 ± 40.0 | 165 – 238 | |

| Ovary | |||

| Length | 158.0 ± 19.2 | 144 – 179 | |

| Width | 103.2 ± 10.6 | 102 – 105 | |

| Egg | |||

| Length | 27.2 ± 1.6 | 26 – 29 | |

| Width | 14.6 ± 2.1 | 13 – 17 |

Body small, oval and elongate, relatively stout, dorso-ventrally flattened, 1490–3300 (2214 ± 991.4) × 500–700 (580 ± 109.5) with a spinous tegument. Mid-body i.e., distance between the posterior margins of ventral sucker to the anterior margin of anterior testis, 645–1700 (1067 ± 577.8); oral sucker ventrosubterminal 223–260 (237.8 ± 20.3) × 188– 210 (196.8 ± 12.0). Ventral sucker located in anterior region of middle third of body, slightly smaller than oral sucker, 157–203 (175.4 ± 25.2) × 130–194 (155.6 ± 35.1) Prephaynx absent. Pharynx muscular and semi-circular, 109.7–182.9 (168.3 ± 32.7) × 73.2–128.0 (109.7 ± 22.4). Oesophagus absent. Intestine branches, run parallel to the body, extending anteriorly but not exceeding the pharynx and reaching close the posterior extremity of the body; all caeca exhibit sinuous diverticula. Testes large, oval, regular in form, tandem, with inter-testicular ovary, located in the posterior third of the body and extending near to posterior end, anterior testis 196–223 (206.8 ± 14.8) × 132–190 (155.2 ± 31.8); posterior testis 165–268 (206.2 ± 56.4) × 165–238 (194.2 ± 40.0).

Cirrus unarmed. Cirrus-pouch long and slender located anterior to anterior testis containing convoluted ejaculatory duct. Pars-prostatica short and surrounded by glandular cells. Seminal vesicle long, broad, saccular and unipartite. Smooth circular swelling surrounding the genital pore. Genital pore ventral, submedial, slightly dextral, anterior to anterior testis. Ovary lobed and regular in form, median located between testes, 144–179 (158.0 ± 19.2) × 102–105 (103.2 ± 10.6). Oviduct connects with seminal receptacle prior to ootype, surrounded by Mehlis’ gland. Uterus extending anteriorly but not exceeding the pharynx, coiled, between caeca. Metraterm present, apparently unarmed, opens into genital atrium. Eggs oval, 26–29 (27.2 ± 1.6) × 13–17 (14.6 ± 2.1), and round in cross-section.

Vitellarium follicular; follicles arranged in dendritic, moniliform system extending throughout most of region between levels of c. 50% of ventral sucker and not exceeding anterior testis, occupying the middle third of the body. Lateral vitelline collecting ducts extend throughout length of vitellarium, uniting to form a fusiform vitelline reservoir ventrally to ovary. Excretory pore terminal; excretory vesicle short that diverges at the end of caeca.

Discussion

A parasitic survey allowed us to report for the first time, in the Caspian Sea area, a digenean identified as Brachylaima sp. isolated from a stray dog. Specimens were assigned to the genus Brachylaima based on the elongated shape of the body, the genital pore and cirrus sac anterior to anterior testis, vitellarium in middle third of the body, oesophagus absent and gonads located in tandem near the posterior extremity (12). Among the Brachylaimidae, the genus Brachylaima is diverse containing several species with very similar morphology (10). However, despite a large number of species reported in the genus, only a few have been extensively described and a complete set of morphological measurements are available i.e., B. ruminae, B. cribbi, B. mascomai, B. llobregatensis and B. aspersae, (13, 8-11) (Table 2). The specimens found in the stray dog in Iran have a smaller average length than specimens described from the five mentioned species (11). In addition, specimens here described differ from other species, except for B. cribbi and B. aspersae, in the presence of a distinct pars prostatica, from B. aspersae in the regular oval form of testes, and from B. cribbi in that vitelline follicle exceeds the posterior margin of ventral sucker (9, 11). However, describing species of Brachylaima using solely morphoanatomical and morphometric characteristics of the adult stages would be incomplete, as those features do not provide enough information on the species’ diversity, and information on the life cycle and developmental stages would be needed (9, 11). Thus, to be conservative, we rather prefer to leave this report as Brachylaima sp.

Table 2:

Mean ± SD (range) of morphological measurements of Brachylaima sp. compared to other four species of Brachylaima. Measurements are given as length × width in micrometers unless otherwise stated.

| Brachylaima sp. n = 5 | B. mascomai n = 56 | B. cribbi n = 30 | B. llobregatensis n = 10 | B. aspersae n. sp. n = 36 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ex. Canis familiaris | ex. Ratus norvegicus | ex. Mus musculus | ex. Mus musculus | ex. Mus musculus | |

| This study | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | |

| Worm body | 2.21 ± 0.99 mm (1.5–3.3) × 0.58 ± 0.1 mm (0.5–0.7) | 3.49 ± 0.52 mm (2.90–4.97) × 0.44 ± 0.04 mm (0.38–0.53) | 5.00 mm (3.8–6.0) × 0.68 mm (0.52–0.79)* | 3.39 ± 0.18 mm (2.08–2.73) × 0.62 ± 36.3 mm (0.56–0.68) | 2.09 ± 0.29 mm (1.42–2.66) × 0.7 ± 0.07 mm (0.51–0.83) |

| Oral Sucker | 237.8 ± 20.3 (223–260) × 196.8 ± 12.0 (188–210) | 237.8 ± 21.5 (197–289) × 218.3 ± 23.5 (180–281) | 259 (230–290) × 279 (250–380)* | 235.9 ± 15.9 (2113–265) × 204–8 ± 16.1 (188.8–233.2) | 248.2 ± 17 (200–275.5) × 222.2 ± 20.1 (167.5–255) |

| Ventral Sucker | 175.4 ± 25.2 (157–203) × 155.6 ± 35.1 (130–194) | 218.2 ± 21.6 (181–265) × 207.7 ± 20.3 (168–253) | 277 (240–320) × 267 (230–300)* | 223.1 ± 19.3 (181–241) × 216.1 ± 22.9 (168.8–237.4) | 258.1 ± 17.3 (215–297.5) × 242.6±18.3 (187.5–270) |

| Pharynx | 168.3±32.7 (109.7–182.9) × 109.7±22.4 (73.2–128.0) | 116.9 ± 15.7 (84–164) × 148.7 ± 17.3 (105–180) | 157 (140–180) × 169 (150–220)* | 117.4 ± 3.4 (112.5–120.6) × 162.3 ± 6.4 (152.7–172.8) | 172.2 ± 13.2 (137.5–195) × 133.8 ± 10.2 (115–157.5) |

| Anterior testis | 206.8 ± 14.8 (196–223) × 155.2 ± 31.8 (132–190) | 297.4 ± 26.4 (236–378) × 251.7 ± 37.0 (192–321) | 419 (280–495) × 353 (240–450)* | 279.4 ± 26.2 (241.2–321.6) × 241.7 ± 27.8 (180.9–265.3) | 261.6 ± 38.2 (57.5–350) × 189 ± 38.7 (125–262.5) |

| Posterior testis | 206.2 ± 56.4 (165–268) × 194.2 ± 40.0 (165–238) | 319.1 ± 52.1 (239–422) × 247.7 ± 37.3 (188–336) | 417 (250–530) × 323 (200–420)* | 304.5 ± 32.7 (253.2–357.7) × 269.8 ± 29.8 (221.1–305.5) | 273.6 ± 40 (195–355) × 216.5 ± 37.6 (145–285) |

| Ovary | 158.0 ± 19.2 (144–179) × 103.2 ± 10.6 (102–105) | 180.7 ± 31.1 (97–241) × 152.1 ± 21.8 (112–221) | 217 (150–260 × 261 (170–320)* | 191.9 ± 12.1 (172.8–209.1) × 125.1 ± 22.3 (88.4–160.8) | 173.9 ± 28.6 (120–267.5) × 132.3 ± 22.1 (87.5–187.5) |

| Egg | 27.2 ± 1.6 (26–29) × 14.6 ± 2.1 (13–17) | 25.4 ± 0.8 (23–27.5) × 12.7 ± 0.2 (12.5–16) | 29.1 (26.32) × 16.6 (16–17.5)* | 30.9 ± 1.0 (29.3–32.5) × 18.2 ± 0.5 (17.6–18.8) | 33.3 ± 1.1 (31–35) × 20.2 ± 2 (18–25) |

SD not provided by the authors.

Species of Brachylaima mostly occur in birds and mammals, and rodents are considered their main definitive hosts (6, 14). Only a few species have been reported in carnivores (15-22), and in only two cases, unidentified Brachylaima has been found in dogs from the North of Spain (23) and from the Khorasan Province in Northeast Iran (5). Most of the species of Brachylaima have been described from the Mediterranean region, and reports from other geographical places are considered introductions, probably imported from Europe (9, 14). Species of Brachylaima use land snails as first and second intermediate hosts (24). So, the economic trade of helicid snails would provide opportunities for species dissemination in a geographical context (14, 24). In Mazandaran Province, helicid snails coming from Europe are commonly found (25). Therefore, we raise the hypothesis that stray dogs might be infected with parasites through the consumption of helicid snails when searching for food in the street, and accordingly to the physiological characteristics of these mammals, worms would be able to fully complete their development.

For more than the last decade, only two species of digeneans have been reported in stray dogs in Iran through sporadic helminthic surveys (26). Moreover, a single record of Brachylaima sp. has been reported from dogs in Northeast Iran (5). Therefore, we contribute to the inventory of helminths in Iran and provide morphometric information for a Brachylaima species. We encourage researchers to place close attention on digeneans in future helminthic surveys in Iran, as for instance, gastrointestinal pathologies in humans have been found to be related to infections of mature Brachylaima species (9, 27).

Conclusion

This is the second report of a species of Brachylaima in Iran and the third digenean species from stray dogs in the area. We want to raise the attention of researchers to helminthic surveys in potential zoonotic reservoirs like stray dogs.

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank all who helped to collect samples from stray dogs and were involved in the preparation of samples for morphological analyses. We are in debt to Dr. Francisco J. Aznar (University of Valencia) for comments on the manuscript, and Dr. Francisco E. Montero (University of Valencia) for elucidating some of the morphological aspects of the material, and assistance in the species illustration. This study was possible thanks to the collaboration between the Department of Parasitology and Mycology, the Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences and the Iranian National Parasitology Museum at the Faculty of Veterinary at Tehran University. The Deputy of Research Affairs of the Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences (Project ID 1548-1393) financially supported this study.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors of this paper declare that there are no conflicts of interests.

References

- 1.Dalimi A, Sattari A, Motamedi G. A study on intestinal helminths of dogs, foxes, and jackals in the western part of Iran. Vet Parasitol. 2006;142(1–2):129–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gholami I, Daryani A, Sharif M, et al. Seroepidemiological survey of helminthic parasites of stray dogs in Sari city, Northern Iran. Pak J Biol Sci. 2011;14(2):133–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gholami SH, Mobedi E, Ziaee H, Sharif M. Intestinal helminths parasites in dog and jackal in different areas of Sari in the years 1992 and 1993. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 1999; 9: 5–12(Persian). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Emamapour SR, Borji H, Nagibi A. An epidemiological survey on intestinal helminths of stray dogs in Mashhad, North-east of Iran. J Parasit Dis. 2015; 39(2):266–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heidari Z. Study on helminthic parasites of domestic and wild canines of North Khorasan Province, northeast Iran with special reference to zoonotic species and genetic variety in Genus Echinococcus. Ph. D thesis. Tehran University of Medical Sciences; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gibson DI, Bray RA, Harris EA. Host– Parasite Database of the Natural History Museum, London URL: http://www.nhm.ac.uk/research-curation/scientific-resources/taxonomy-systematics/host-parasites/database/index.jsp. 2005: accessed, April 2016.

- 7.Ghorbani M. Nature of Iran and its climate. In: Ghorbani M, editors. The economic geology of Iran. Dordrecht: Springer; 2013. p. 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gracenea M, González-Moreno O. Life cycle of Brachylaima mascomai n. sp. (Trematoda: Brachylaimidae), a parasite of rats in the Llobregat Delta (Spain). J Parasitol. 2002;88(1):124–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butcher AR, Grove DI. Description of the life-cycle stages of Brachylaima cribbi n. sp. (Digenea: Brachylaimidae) derived from eggs recovered from human faeces in Australia. Syst Parasitol. 2001;49(3):211–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.González-Moreno O, Gracenea M. Life cycle and description of a new species of brachylaimid (Trematoda: Digenea) in Spain. J Parasitol. 2006;92(6):1305–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Segade P, Crespo C, García N, et al. Brachylaima aspersae n. sp. (Digenea: Brachylaimidae) infecting farmed snails in NW Spain: Morphology, life cycle, pathology, and implications for heliciculture. Vet Parasitol. 2011;175(3–4):273–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pojmanska T. Family Brachylaimaidae Joyeux & Foley, 1930. In: Gibson DI, Jones A, Bray RA, editors. Keys to the Trematoda Vol. 1. London: CAB International and Natural History Museum; 2002. p. 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mas-Coma S, Montoliu I. The life cycle of Brachylaima ruminae n. sp. (Trematoda: Brachylaimidae), a parasite of rodents. Z Parasitenkd. 1986;72(6):739–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cribb TH. Introduction of a Brachylaima species (Digenea: Brachylaimidae) to Australia. Int J Parasitol. 1990;20(6):789–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skírnisson K, Eydal M, Gunnarsson E, et al. Parasites of the Arctic fox (Alopes lagopus) in Iceland. J Wildl Dis. 1993;29(3):440–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richards DT, Harris S, Lewis JW. Epidemio-logical studies on intestinal helminth parasites of rural and urban red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) in the United Kingdom. Vet Parasitol. 1995;59(1):39–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Torres J, Garciá-Perea R, Gisbert J, et al. Helminth fauna of the Iberian lynx, Lynx pardinus. J Helminthol. 1998;72(3):221–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ching HL, Leighton BJ, Stephen C. Intestinal parasites of racoons (Procyonlotor) from southwest British Columbia. Can J Vet Res. 2000;64(2):107–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamada D. Studies on the parasite fauna of raccoon (Procyon lotor) naturalized in Hokkaido, Japan. Jpn J Vet Res. 2000; 48:70–71. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Torres J, Miquel J, Motjé M. Helminth parasites of the Eurasian badger (Meles meles L.) in Spain: a biogeographic approach. Parasitol Res. 2001;87(4):259–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Segovia JM, Torres J, Miquel J. The red fox, Vulpes vulpes L., as a potential reservoir of zoonotic flukes in the Iberian Peninsula. Acta Parasitol. 2002; 47: 163–166. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pence DB, Tewes ME, Laack LL. Helminths of the Ocelot from Southern Texas. J Wildl Dis. 2003;39(3):683–9.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guisantes JA, Benito A, Estibalez JJ, Mas-Coma S. High parasite burdens by Brachylaima (Brachylaima) sp. (Trematoda: Brachylaimidae) in two dogs in the north of Spain. Rev Iber Parasitol. 1994; 54: 255–258. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gállego L, González-Moreno O, Gracenea M. Terrestrial edible land snails as vectors for geographic dissemination of Brachylaima species. J Parasitol. 2014;100(5):674–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salahi-Moghaddam A, Mahvi AH, Mowlavi GR, et al. Parasitological study on Lymnaea palustris and its ecological survey by GIS in Mazandaran province. Modares J Med Sci. 2009; 11: 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dalimi A, Mobedi I. Helminth parasites of carnivores in Northern Iran. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1992;86(4):395–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Butcher AR, Parasuramar P, Thompson CS, et al. First report of the isolation of an adult worm of the genus Brachylaima (Digenea: Brachylaimidae), from the gastrointestinal tract of a human. Int J Parasitol. 1998;28(4):607–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]