Abstract

Background: Although family caregivers provide a significant portion of health and support services to adults with serious illness, they are often marginalized by existing healthcare systems and procedures.

Objective: We examine the role of caregivers in existing systems of care, identify needed changes in structures and processes, and describe how these changes might be monitored and assessed and who should be accountable for implementing them.

Design: Based on a broad assessment of the caregiving literature, the recent National Academy of Sciences Report on family caregiving, and descriptive data from two national surveys, we describe structural and process barriers that limit caregivers' ability to provide effective care.

Subjects: To describe the unique challenges and impacts of caring for seriously ill patients, we report data from a nationally representative sample of older adults and their caregivers (National Health and Aging Trends Study [NHATS]; National Study of Caregiving [NSOC]) to identify the prevalence and impact on family caregivers of seriously ill patients who have high needs for support and are high cost to the healthcare system.

Measurements: Standardized measures of patient status and caregiver roles and impacts are used.

Results: Multiple structural and process barriers limit the ability of caregivers to provide effective care. These issues are exacerbated for the more than 13 million caregivers who provide care and support to 9 million seriously ill older adults.

Conclusions: Fundamental changes are needed in the way we identify, assess, and support caregivers. Educational and workforce development reforms are needed to enhance the competencies of healthcare and long-term service providers to effectively engage caregivers.

Keywords: : family caregiver training, financial concerns, role of family caregivers, support for family caregivers

Introduction

Nearly 18 million family caregivers, broadly defined as relatives, partners, friends, or neighbors, provide care and support to older adults because of limitations in their physical, mental, or cognitive functioning.1 Millions more provide care and support to younger individuals with serious illness and disability. Family caregivers arrange and attend medical appointments, participate in routine and high-stakes treatment decisions, coordinate care and services, help with daily tasks such as dressing and bathing, manage medicines, obtain and oversee the use of medical equipment, and ensure that needs for food and shelter are met. Family members have always been the primary source of support and assistance to older parents, grandparents, and other family members during times of illness and when they can no longer function independently. What has changed in the last few decades is that this job has become more complex and longer lasting because of medical advances, shorter hospital stays, and increased longevity.

The goal of this article is to examine the role of caregivers in existing systems of care, identify needed changes in structures and processes, how these changes might be monitored and assessed, and who should be accountable for these changes. We begin by identifying structural and process barriers that limit caregivers' ability to provide effective care to caregivers of all older adults with illness and disability, including those with serious illness. We argue that addressing these barriers will require fundamental changes in the way we (1) identify and assess caregivers; (2) support them; and (3) train healthcare and long-term service and support (LTSS) providers to effectively engage caregivers.

To better understand the role of caregiving for seriously ill patients, we also focus on caregiving for three types of high-need and high-cost patients—those with multiple chronic conditions, dementia, and/or are at end of life. These individuals fit the definition for serious illness, “a condition that carries a high risk of mortality and either negatively impacts a person's daily function or excessively strains their caregivers”,2 and represent subgroups of patients for whom the stakes for caregivers, patients, and society are especially high. We describe the prevalence of these populations using recent national data and describe how they affect caregiving roles and outcomes. Note that we use the terms high need and seriously ill interchangeably in this article, and we acknowledge that the three patient groups we focus on do not represent all seriously ill patients.

Structural and process barriers to effective care

To fulfill their roles, caregivers serve as the glue that connects healthcare and social service providers to the individual in need of care. They interact with physicians, nurses, social workers, psychologists, pharmacists, physical and occupational therapists, direct care workers, and others. In addition to being direct care providers for the patient, they also serve as the primary source of information about the patient's health history, abilities, and preferences. Yet, family caregivers are often marginalized in the delivery of healthcare and LTSS.

A confluence of structural and process barriers impedes effective partnerships between family caregivers and other providers of care. The prevailing emphasis on supporting individual autonomy and safeguarding the privacy of personal health information limits family caregivers' access to information that is appropriate and beneficial when they are responsible for coordinating care or managing treatments. Medical providers are not compensated for time spent educating family caregivers about patients' medical conditions and treatments, nor are they trained to have those conversations. Although clinical assessments used to formulate treatment plans commonly include questions for patients about the availability of help, caregivers are not asked about their ability to provide care or their relevant knowledge, and receipt of training in performing caregiving tasks is inconsistent at best. The availability and adequacy of family caregiving are simply assumed.1

Guidance on how to address these issues is provided by the recent National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine report on family caregiving,1 which calls for transformation in the policies and practices affecting the role of families in the support and care of older adults, stating that today's emphasis on person-centered care needs to evolve into a focus on person- and family-centered care. Although focused specifically on caregiving for older adults, the recommendations apply equally well to caregiving for adults of all ages. We focus, in this study, on those policy recommendations relevant to the key structures and processes of care that need to be changed to fully integrate caregivers into healthcare and LTSS systems.

Identifying and assessing caregivers

Caregivers' circumstances vary widely and in ways that affect their availability, capacity, and willingness to assume critical responsibilities. Evidence from randomized clinical trials indicates that most effective interventions begin with an assessment of caregivers' risks, needs, strengths, and preferences.3,4 Yet most health and LTSS providers do not assess the health, skills, employment, and willingness of family caregivers and provide them little, if any, training to carry out the complicated medical procedures, personal care, and care coordination tasks they are expected to provide. Indeed, the lack of systematic assessment of family participation in health and LTSS not only affects the experience of family caregivers and care recipients but also precludes knowledge of how their involvement influences the quality of clinical care and social services, and undermines credible accounting of the value family caregivers bring to the healthcare delivery system and society.

Optimizing the role of family caregivers will minimally require systematic attention to the identification, assessment, and support of family caregivers throughout the care delivery process. How might this be achieved? First, caregivers need to be identified in both the care recipient's and the caregiver's medical record (Table 1). This acknowledges their role as part of a care team and sensitizes providers to the importance of engaging the caregiver when making patient treatment plans. Second, caregivers should be screened to identify those at risk for adverse health outcomes and whose circumstances may place the person they care for in harm's way. Achieving this goal will require new tools that assess caregivers' strengths, limits, needs, and risks in relationship to the range of tasks they are expected to perform. Assessments should minimally include caregivers' health and functional status, their level of stress and well-being, their ability to perform required tasks, and the types of training and supports they might need to enact their role. These assessments should occur during all key provider patient/caregiver encounters, including wellness exams, physician visits, admission and discharge from hospitals and emergency rooms, and chronic care coordination and care transition programs.

Table 1.

Caregiver Assessment

| Who | When | What | Where | Assessor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identify primary caregiver responsible for patient care; entered in patient and caregiver medical record | • Wellness/follow-up visits for patient/caregiver • Care transitions (admission/discharge from hospitals, emergency rooms/rehab facilities to home) • Chronic care transitions/change in patient status • Regular follow-up monitoring |

• Health/functional and emotional status of caregiver • Knowledge and skills for required care tasks • Willingness to carry out required tasks • Financial and human support resources available to caregiver • Training and support needed |

• Physician offices • Receiving/discharge facility • Caregiver/patient home • Hospital • Nursing home • Hospice |

• Primary care provider • Discharge planners • In-home assessors • Caregiver specialists |

Key initial steps to implementing this recommendation will require identification and refinement of caregiver assessment tools appropriate to the care delivery context of the care recipient, identification and training of assessors, and evaluation of provider work flow to determine where and when assessments take place. The health, functional ability, and care needs of the patient should be a key factor in determining the fit between patient needs and caregiver capacity, which in turn should inform the training and support needs of the caregiver.

With few exceptions, there are no financial incentives for providers to identify, assess, or support family caregivers or penalties for not doing so. For example, the Caregivers and Veterans Omnibus Health Services Act of 2010 established a mechanism for reimbursement/workload credit for services provided to family caregivers, but the focus is primarily on caregivers of younger veterans.5 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services should be charged with developing testing and implementing provider payment reforms that motivate providers to engage family and support caregivers. Payment reforms should include clearly articulated performance standards that hold providers accountable for caregiver engagement, training, and support by explicitly including caregiver outcomes in quality measures. Outcome measures should include caregiver satisfaction with provider encounters, adequacy of training and instructions provided, caregivers' confidence and efficacy in performing required tasks, and the adequacy of support services provided.

Both process measures identified in Table 1 and outcome measures listed above should receive high priority for further development with the goal of meeting the standards and endorsement of the National Quality Forum. We envision a measurement strategy that includes a common core that can be used across care settings along with a set of context specific measures that capture the unique caregiving challenges for patients in hospital, nursing home, hospice, and home care settings.

The recommendations made above stand in sharp contrast to the current reality of caregiver assessment in our healthcare system. The Caregiver Advise, Record, Enable (CARE) Act enacted in more than 20 states is one small step in the right direction as it encourages hospitals to (1) record the name of the family caregiver at the time of hospital admission of their loved one; (2) provide family caregivers with adequate notice before hospital discharge; and (3) provide simple instruction of the medical tasks they will be performing when their loved one returns home.6 Proposed national legislation such as the Recognize, Assist, Include, Support, and Engage (RAISE) Family Caregivers Act is a bipartisan bill that would create a national plan to support the more than 40 million Americans caring for older adults, spouses, children with disabilities, veterans, and other people who need care to live independently.7,8

Supporting caregivers

Guidance on how best to support caregivers can be gleaned from a large body of intervention research aimed at improving caregiver and patient outcomes. Education and skills training improve caregiver confidence and the ability to manage daily care challenges. Training strategies that involve active participation of the caregiver are particularly effective in achieving positive outcomes.9 Counseling, self-care, relaxation training, and respite programs can improve caregivers' and patients' quality of life.3,10 Technology-based caregiver support, education, and skills training can be an effective and efficient alternative for enhancing caregiver knowledge and skills.11

Despite the demonstrated effectiveness of a wide range of caregiver services and supports, few of these intervention strategies have moved from research settings to everyday health and social service programs. Key questions that need to be addressed in pursuing widespread implementation of proven interventions include who should deliver these support strategies, where and when should they be delivered, how can they be integrated into the existing workflow of provider organizations, and who should pay for their delivery and evaluation? The National Family Caregiver Support Program (NFCSP) of the Administration for Community Living is one example of a federal program that incorporates elements of evidence-based caregiver interventions into broad-based service programs for caregivers.12 These relatively modest efforts should be scaled up and expanded. At the same time, we should continue to support efficacy trials aimed at developing and refining support strategies for caregivers.

Enhancing competencies of healthcare and LTSS providers to engage caregivers

Providers should see family caregivers not just as a resource in the treatment or support of a person, but rather as a partner in that enterprise who may need information, training, care, and support. Achieving and acting on that perspective require that providers have the skills to recognize a caregiver's presence, assess whether and how the caregiver can best participate in overall care, engage and share information with the caregiver, recognize the caregiver's own healthcare and support needs, and refer the caregiver to needed services and supports.

A wide range of professionals and direct care workers are likely to interact with family caregivers—physicians, nurses, social workers, psychologists, pharmacists, occupational therapists, physical and other rehabilitation therapists, certified nursing assistants, physician assistants, and others. Professional organizations in nursing and social work have led the way in taking steps to establish standards for person- and family-centered care that include the caregiver. Similar efforts are needed across the healthcare and social service professions.13,14 Federal support is needed from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) for the development and enforcement of competencies for identifying, assessing, and supporting family caregivers by healthcare and human service professionals. Achieving this goal requires that specific competencies are identified by provider type, including competencies related to working with diverse family caregivers. These competencies should in turn shape the development of educational curricula and training programs designed to teach them. Professional societies and accrediting bodies should develop educational curricula and support their systematic evaluation and implementation, and should convene and collaborate with state agencies and professional organizations to incorporate competencies into standards for licensure and certification.

Seriously ill patients and their caregivers

Although the preceding recommendations apply to caregiving broadly defined, they take on special significance when caring for seriously ill high-need/high-cost patients where the intensity, duration, and adverse impact of caregiving reach extreme levels. To better understand the impact of seriously ill patients on caregivers, we analyzed the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) and National Study of Caregiving (NSOC) data to identify the types of tasks performed by caregivers and caregiver outcomes for three types of patients: (1) patients who have three or more chronic diseases and a functional limitation in their ability to care for themselves or perform routine daily tasks15; (2) patients with a diagnosis of probable dementia; and (3) patients at the end of life, defined as individuals who died within one year of baseline assessment.16,17 Together, these three groups represent some of the highest cost patients in the United States, accounting for majority of health and long-term care expenditures.18–21 In addition, family caregivers provide billions of hours of unpaid care to these populations annually. For example, the Alzheimer's Association estimated that in 2015, 15.9 million family and friends provided 18.1 billion hours of unpaid care to those with Alzheimer's and other dementias, an economic value of $221 billion.22

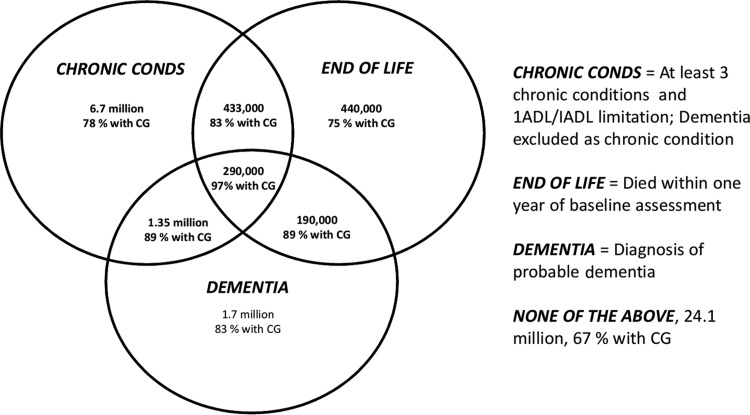

Inasmuch as there is overlap among the three groups, we also examined all possible combinations of these three groups to explore the additive effects of, for example, caring for patients who have multiple chronic conditions, dementia, and are at end of life. This overlap is clearly illustrated in Figure 1 with corresponding population estimates based on NHATS (patient population, N = 7609). In this nationally representative sample of adults (NHATS) aged 65 and over, 35% of 35.3 million older adults met criteria for at least one of the three groups of interest. Six percent met criteria for at least two categories, and slightly less than 1% (290,000 persons) met criteria for all three; they had dementia, at least three chronic conditions and a functional limitation, and died within a year. We also show in Figure 1 the proportion of patients in each group who received help from an unpaid caregiver, ranging from 75% of patients at the end of life to 97% for patients who met criteria for all three groups.

FIG. 1.

Three overlapping patient populations and proportion with at least one unpaid CG. Source: NHATS (2011, N = 7609); noninstitutionalized U.S. older adults aged 65 and over, 35.3 million, weighted population estimates. CG, caregiver; NHATS, National Health and Aging Trends Study.

Table 2 provides context information about caregiving, including the duration and number of hours of care provided per month, and Table 3 summarizes the types of tasks performed by caregivers for each of the three groups and their combinations. As shown in Table 2, caregivers of patients who meet multiple high-need categories provide considerably more hours of care than caregivers of low-need patients. For example, 33% caregivers of patients with chronic conditions, dementia, and who are at end of life, provided more than 100 hours of care per month compared to 14% of caregivers caring for low-need patients. Table 3 shows that caregivers of high-need patients are more likely to provide help with virtually all types of tasks when compared to caregivers of low-need patients. With a few exceptions, the level of caregiver help provided is highest among caregivers caring for individuals who meet criteria for all three groups, followed by caregivers caring for persons meeting criteria for two of the three groups.

Table 2.

Caregiving Context by Patient Category

| Low needa | Chron conds | Died | Dementia | Dementia+died | Chron conds+died | Chron conds+dementia | Chron conds+dementia+died | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 444 | 714 | 49 | 274 | 47 | 53 | 326 | 89 |

| Weighted population estimates (millions) | 4.30 | 6.80 | 0.41 | 2.20 | 0.37 | 0.60 | 2.60 | 0.70 |

| Relationship to CR (%) | ||||||||

| Spouse | 26.3 | 13.7 | 18.0 | 13.7 | 23.1 | 24.0 | 15.1 | 8.9 |

| Daughter/daughter-in-law/stepdaughter | 27.7 | 28.5 | 35.9 | 24.0 | 30.7 | 38.1 | 42.0 | 52.7 |

| Son/son-in-law/stepson | 22.0 | 20.5 | 20.5 | 35.1 | 19.7 | 10.3 | 22.0 | 25.7 |

| Other | 24.0 | 37.3 | 25.6 | 27.1 | 26.5 | 27.6 | 20.8 | 12.8 |

| Lives with CR (%) | 41.4 | 47.2 | 39.3 | 41.2 | 46.3 | 56.8 | 46.6 | 41.5 |

| CR has paid help (%) | 18.1 | 18.6 | 18.6 | 18.2 | 17.6 | 28.3 | 26.2 | 31.6 |

| Years of caregiving (%) | ||||||||

| 1 or less | 18.6 | 11.5 | 11.8 | 8.4 | 14.8 | 31.2 | 12.6 | 14.9 |

| 2–4 | 30.5 | 36.9 | 41.1 | 29.7 | 34.7 | 36.9 | 35.6 | 36.0 |

| 5–10 | 32.6 | 34.5 | 32.1 | 59.8 | 33.9 | 25.9 | 41.6 | 36.8 |

| >10 | 18.3 | 17.1 | 15.0 | 2.0 | 16.7 | 6.0 | 10.3 | 12.4 |

| Hours of caregiving per month (%) | ||||||||

| 1–16 | 41.2 | 30.7 | 30.4 | 27.0 | 36.4 | 17.5 | 21.3 | 24.7 |

| 17–40 | 23.0 | 33.4 | 26.8 | 20.0 | 24.7 | 19.6 | 28.6 | 17.0 |

| 41–100 | 21.7 | 23.6 | 24.5 | 21.0 | 22.4 | 38.8 | 23.1 | 24.8 |

| >100 | 14.1 | 12.3 | 18.3 | 32.1 | 16.5 | 24.1 | 27.0 | 33.5 |

National Study of Caregiving (NSOC, 2011).

Patient does not meet high-need patient criteria, but has limitations in IADL and/or ADL.

ADL, activities of daily living; CR, care recipient; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living.

Table 3.

Types of Caregiving Tasks by Patient Category

| Low needa | Chron conds | Died | Dementia | Dementia+died | Chron conds+died | Chron conds+dementia | Chron conds+dementia+Died | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CG tasks | ||||||||

| How often did you help… (every day or most days) (% yes) | ||||||||

| With chores | 39.2 | 43.0 | 44.9 | 44.3 | 43.3 | 62.3 | 49.0 | 50.7 |

| With personal care | 9.3 | 14.7 | 20.0 | 22.9 | 33.7 | 36.6 | 24.1 | 37.7 |

| Drive CR places | 22.8 | 26.3 | 17.7 | 23.8 | 18.2 | 22.5 | 23.4 | 14.4 |

| Help CR get around his/her home | 13.1 | 19.2 | 11.9 | 20.3 | 37.8 | 41.2 | 25.4 | 38.5 |

| Did you help… (% yes) | ||||||||

| Keep track of meds | 38.8 | 43.0 | 39.9 | 58.8 | 50.2 | 48.5 | 66.1 | 73.8 |

| CR take shots or injections | 4.7 | 8.8 | 3.1 | 7.7 | 11.7 | 8.2 | 8.9 | 12.4 |

| Manage medical tasks | 4.1 | 11.3 | 11.2 | 9.9 | 15.9 | 8.0 | 16.3 | 23.0 |

| With special diet | 19.5 | 31.8 | 25.6 | 22.9 | 16.6 | 27.8 | 32.2 | 37.4 |

| With skin care wounds | 18.3 | 24.2 | 24.2 | 17.2 | 19.2 | 20.7 | 30.1 | 41.6 |

| Make medical appointments | 50.1 | 55.7 | 64.3 | 75.9 | 79.4 | 48.9 | 73.2 | 74.5 |

| Speak to medical provider | 42.8 | 51.3 | 48.8 | 68.4 | 78.2 | 54.9 | 67.3 | 69.3 |

| Add/change health insurance | 22.3 | 23.1 | 16.9 | 31.2 | 35.0 | 28.5 | 26.8 | 36.1 |

| With other insurance matters | 27.6 | 31.7 | 30.3 | 42.8 | 52.4 | 18.0 | 41.4 | 38.6 |

National Study of Caregiving (NSOC, N = 1996, 2011).

Patient does not meet high-need patient criteria, but has limitations in IADL and/or ADL.

CG, caregiver.

An extensive literature shows that caregivers are at increased risk of physical and psychiatric morbidity.1,23 They experience emotional distress, depression, anxiety, and social isolation. When the intensity and duration of caregiving is high, self-care and physical health of the caregiver may be impaired. In the NSOC sample, nearly half of all caregivers report emotional difficulty in caring for their loved one, and one fifth report financial and physical difficulty in providing care. These rates are consistently higher among caregivers of high-need patients.24

In sum, these data show that caregivers of high-need patients provide large amounts of care over extended periods of time and they are at risk for adverse outcomes jeopardizing their own and the care recipient's well-being. Identifying, assessing, and supporting these caregivers will be essential to a healthcare system that depends on them to provide the lion's share of the care for these patients. Accomplishing these goals will require assessment tools tailored to these populations, support options that address the unique challenges faced by these caregivers, and new training programs that prepare providers to effectively engage caregivers of these populations.

Because seriously ill patients are likely to experience more rapid changes in symptomatology and functional status than other patients, it will be important to closely monitor patient status and the caregiver's ability to address changing patient needs. The high intensity of caregiving demands also puts the caregiver at risk for adverse health outcomes, making it all the more important to monitor caregiver stress and emotional and physical well-being. Frequent and effective communication between caregivers, patients, and the healthcare team will be essential to achieving these goals. Supporting caregivers of seriously ill patients should focus on their role in managing pain and other symptoms, teaching them the philosophy and “how to” of providing comfort care, negotiating care transitions, and addressing the psychological distress and physical health needs of caregivers.

Conclusion

The availability of family caregivers in the future is threatened by the higher rates of childlessness among baby boomers, smaller and more geographically dispersed families, and increasing participation of women in the labor force. At the same time, advances in medicine that save and extend lives increase the duration, complexity, and technical difficulty of care required by individuals with serious illness and disability. Family caregivers will continue to play a vital role in existing healthcare and LTSS systems. However, their willingness to provide care and their effectiveness in doing so will depend on fundamental changes in the extent to which we formally recognize them as key contributors to the health of their relatives, integrate them into the formal provider systems, and support them to do their job. The stakes are high, particularly for high-need, high-cost patients whose quality of life critically depends on the availability of a family caregiver, and for society as a whole responsible for providing high-quality and cost-effective care.

Acknowledgment

Preparation of this article was supported by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Emily Kelly Roseburgh Memorial Fund of the Pittsburgh Foundation, and the Stern Family Foundation.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Schulz R, Eden J. (eds): Families Caring for an Aging America. Washington, DC: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, The National Academies Press, 2016 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teno JM, Price RA, Makaroun LK: Challenges of measuring quality of community-based programs for seriously ill individuals and their families. Health Aff 2017;36:1227–1233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belle SH, Burgio L, Burns R, et al. : Enhancing the quality of life of dementia caregivers from different ethnic or racial groups. Ann Intern Med 2006;145:727–738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Czaja SJ, Gitlin LN, Schulz R, et al. : Development of the risk appraisal measure: A brief screen to identify risk areas and guide interventions for dementia caregivers. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:1064–1072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Congress.gov.: Public Law 111-1563-May 5, 2010. Caregivers and Veterans Omnibus Health Services Act of 2010. www.congress.gov/111/plaws/publ163/PLAW-111publ163.pdf (Last accessed June20, 2017)

- 6.AARP: New state law to help family caregivers-December 2015. www.aarp.org/politics-society/advocacy/caregiving-advocacy/info-2014/aarp-creates-model-state-bill.html (Last accessed June22, 2017)

- 7.Congress.gov: S.1719-RAISE Family Caregivers Act.-December 2016. www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/senate-bill/1719 (Last accessed February24, 2017)

- 8.Given BA, Reinhard SC: Caregiving at the end of life: The challenges for family caregivers. Generations 2017;41:50–57 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schulz R, O'Brien A, Czaja S, et al. : Dementia caregiver intervention research: In search of clinical significance. Gerontologist 2002;42:589–602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mittelman MS, Ferris SH, Shulman E, et al. : A comprehensive support program: Effect on depression in spouse-caregivers of AD patients. Gerontologist 1995;35:792–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Czaja SJ, Lee CC, Schulz R: Quality of life technologies in supporting family caregivers. In: Schulz R. (ed): Quality of Life Technology Handbook. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press/Taylor and Francis Group, 2013, pp. 245–260 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Administration for Community Living: National Family Caregiver Support Program (NFCSP). www.acl.gov/programs/support-caregivers/national-family-caregiver-support-program (Last accessed June20, 2017)

- 13.Kelly K, Reinhard S, Brooks-Danso A: Professional partners supporting family caregivers. Am J Nurs 2008;108:6–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Association of Social Workers: NASW Standards for Social Work Practice with Family Caregivers of Older Adults-2010. www.socialworkers.org/practice/standards/NASWFamilyCaregiverStandards.pdf (Last accessed June22, 2017)

- 15.Hayes SL, Salzberg CA, McCarthy D, et al. : High-need, high-cost patients: Who are they and how do they use health care—A population-based comparison of demographics, health care use, and expenditures. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund)2016;26:1–14 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Health and Aging Trends Study: Produced and distributed by www.nhats.org with funding from the National Institute on Aging (Grant Number NIA U01AG32947)

- 17.National Study of Caregiving: Produced and distributed by www.nhats.org with funding from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services' Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation in cooperation with the National Institute on Aging (Grant Number NIA U01AG32947)

- 18.Kelley AS, McGarry K, Gorges R, Skinner JS: The burden of health care costs for patients with dementia in the last 5 years of life. Ann Intern Med 2015;163:729–736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hurd MD, Martorell P, Langa KM: Monetary costs of dementia in the United States. New Engl J Med 2013;369:489–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riley GF, Lubitz JD: Long-term trends in Medicare payments in the last year of life. Health Serv Res 2010;45:565–576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hogan C, Lunney J, Gabel J, Lynn J: Medicare beneficiaries' costs of care in the last year of life. Health Aff 2001;20:188–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alzheimer's Association: Factsheet: Alzheimer's disease caregivers-March 2016. http://act.alz.org/site/DocServer/caregivers_fact_sheet.pdf?docID=3022 (Last accessed February24, 2017)

- 23.Schulz R, Sherwood P: Physical and mental health effects of family caregiving. Am J Nurs 2008;108:23–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wolff JL, Spillman BC, Freedman VA, Kasper JD: A national profile of family and unpaid caregivers who assist older adults with health care activities. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:372–379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]