Abstract

Background: High-quality care for seriously ill patients aligns treatment with their goals and values. Failure to achieve “goal-concordant” care is a medical error that can harm patients and families. Because communication between clinicians and patients enables goal concordance and also affects the illness experience in its own right, healthcare systems should endeavor to measure communication and its outcomes as a quality assessment. Yet, little consensus exists on what should be measured and by which methods.

Objectives: To propose measurement priorities for serious illness communication and its anticipated outcomes, including goal-concordant care.

Methods: We completed a narrative review of the literature to identify links between serious illness communication, goal-concordant care, and other outcomes. We used this review to identify gaps and opportunities for quality measurement in serious illness communication.

Results: Our conceptual model describes the relationship between communication, goal-concordant care, and other relevant outcomes. Implementation-ready measures to assess the quality of serious illness communication and care include (1) the timing and setting of serious illness communication, (2) patient experience of communication and care, and (3) caregiver bereavement surveys that include assessment of perceived goal concordance of care. Future measurement priorities include direct assessment of communication quality, prospective patient or family assessment of care concordance with goals, and assessment of the bereaved caregiver experience.

Conclusion: Improving serious illness care necessitates ensuring that high-quality communication has occurred and measuring its impact. Measuring patient experience and receipt of goal-concordant care should be our highest priority. We have the tools to measure both.

Keywords: : goal-concordant care, quality measurement, serious illness communication

Introduction

High-quality care in serious illness aligns treatment with patients' known goals and values. Therefore, quality measures should reflect our ability to deliver “goal-concordant” care. When we fail to provide care that matches patients' preferences, we commit a medical error, no less urgent than any other harmful error. Communication between clinicians and patients or their surrogates (hereafter, “communication”) enables goal-concordant care, thus, measuring communication in serious illness may enhance patient safety. Poor communication can also harm seriously ill patients.1 Therefore, a healthcare system that endeavors to provide the highest quality care to the sickest patients must ensure that high-quality communication occurs and results in the desired outcomes. This raises several questions: What is high-quality communication? How does it impact seriously ill patients and their families? How does it precipitate goal-concordant care? And, how do we measure it?

This article suggests a conceptual framework for the processes that contribute to goal-concordant care and that may assist in quality improvement, accountability schemes, or both. We identify quantifiable variables for these processes, review challenges and opportunities related to measuring them, and examine how they may be implemented.

Communication, Shared Decision Making, and Quality Measurement in Serious Illness

A serious illness carries a high risk of mortality AND either negatively impacts a person's daily function or quality of life, OR excessively burdens their caregivers.2 Communication plays several roles in the experience of patients with serious illness. First, serious illness frequently requires complex decision making, which entails communication about the risks, benefits, and uncertainties of treatment. Second, serious illness may not only directly limit one's cognitive ability, but it also heightens anxiety for patients and families,3 undermining critical thinking abilities.4 Clinicians, therefore, must respond to emotion when attempting to convey understandable and actionable care options. Finally, treatment decisions typically involve the risk of hastened mortality or prolonged dying, which raise the stakes of communication.

National consensus bodies promote shared decision making (SDM) as the dominant model for communication in such settings.5,6 Experts define SDM as “an interpersonal, interdependent process in which the healthcare provider and the patient relate to and influence each other as they collaborate in making decisions about the patient's healthcare.”7 Clinicians may influence patients by sharing medical knowledge and experience, and patients may influence clinicians by disclosing values and goals relevant to the application of that knowledge. This patient-centered process intends to support the receipt of goal-concordant care.

Existing national quality frameworks for seriously ill patients inadequately capture this outcome or the communication processes and qualities that likely facilitate it. National Quality Forum-endorsed process measures encourage the documentation of treatment preferences or “care plans,” activities that presuppose, but fail to guarantee, that high-quality communication has taken place (Table 1). Most existing quality measures refer implicitly or explicitly to life-sustaining treatments alone. Several assess the utilization of hospice or of potentially nonbeneficial treatments near the end of life (EOL).

Table 1.

National Quality Forum Endorsed Quality Measures That Relate to But Do Not Ensure That High-Quality Communication Has Occurred

| NCP guideline (cite) | Program | Measure name | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.2: The care plan is based on the identified and expressed preferences, values, goals, and needs of the patient and family and is developed with professional guidance and support for patient–family decision making. Family is defined by the patient. | Hospice QRPa | Treatment preferences (NQF no. 1641) | Percentage of patients with chart documentation of preferences for life-sustaining treatments. |

| PQRSb | Advance care plan (NQF no. 0326)c | Percentage of patients aged 65 years and older who have an advance care plan or surrogate decision maker documented in the medical record or documentation in the medical record that an advance care plan was discussed, but the patient did not wish or was not able to name a surrogate decision maker or provide an advance care plan. | |

| Home Health Quality Reporting, Home Health Value-Based Purchasing | HHCAHPS communications between providers and patients (NQF no. 0517) | Multi-item scale with multiple measures accounting for elements and qualities of communication between home health provider and patient. | |

| n/a | Patients admitted to ICU who have care preferences documented (NQF no.) | Percentage of vulnerable adults admitted to ICU who survive at least 48 hours who have their care preferences documented within 48 hours OR documentation as to why this was not done. | |

| 7.2 The IDT assesses and, in collaboration with the patient and family, develops, documents, and implements a care plan to address preventative and immediate treatment of actual or potential symptoms, patient and family preferences for site of care, attendance of family and/or community members at the bedside, and desire for other treatments and procedures. | n/a | Proportion… receiving chemotherapy in the last 14 days of life. (NQF no. 0210) | Percentage of patients who died from cancer receiving chemotherapy in the last 14 days of life. |

| … with more than one emergency room visit in the last day of life. (NQF no. 0211) | Percentage of patients who died from cancer with more than one emergency room visit in the last 30 days of life. | ||

| …with more than one hospitalization in the last 30 days of life. (NQF no. 0212) | Percentage of patients who died from cancer with more than one hospitalization in the last 30 days of life. | ||

| …admitted to the ICU in the last 30 days of life. (NQF no. 0213) | Percentage of patients who died from cancer admitted to the ICU in the last 30 days of life. | ||

| …dying from Cancer in an acute care setting. (NQF no. 0214) | Percentage of patients who died from cancer dying in an acute care setting. | ||

| …not admitted to hospice. (NQF no. 0215) | Percentage of patients who died from cancer not admitted to hospice. | ||

| …admitted to hospice for less than 3 days (NQF no. 0216) | Percentage of patients who died from cancer, and admitted to hospice and spent less than 3 days there. | ||

| Department of Veterans Affairs | Bereaved Family Survey | Assesses families' perceptions of the quality of care that Veterans received from the VA in the last month of life. The BFS consists of 19 items (17 structured and 2 open-ended). |

Quality reporting program.

Physician quality reporting system.

This measure is also included in NCP domain 7.2

BFS, bereaved family survey; HHCAHPS, Home Health Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems; ICU, intensive care unit; IDT, interdisciplinary team; PQRS, physician quality reporting system; QRP, quality reporting program; VA, Department of Veterans Affairs.

Recognizing these shortcomings, several national organizations promote goal-concordant care as a quality indicator for seriously ill patients.8–10 Yet, measuring goal-concordant care directly poses formidable methodological challenges, including documentation of nonspecific or potentially irrelevant treatment preferences, poor documentation of those preferences, instability of preferences over time, and challenges related to determining “agreement” between preferences and outcomes.11 Because of these challenges, healthcare systems may consider measuring indicators that either predict goal concordance or result from it.

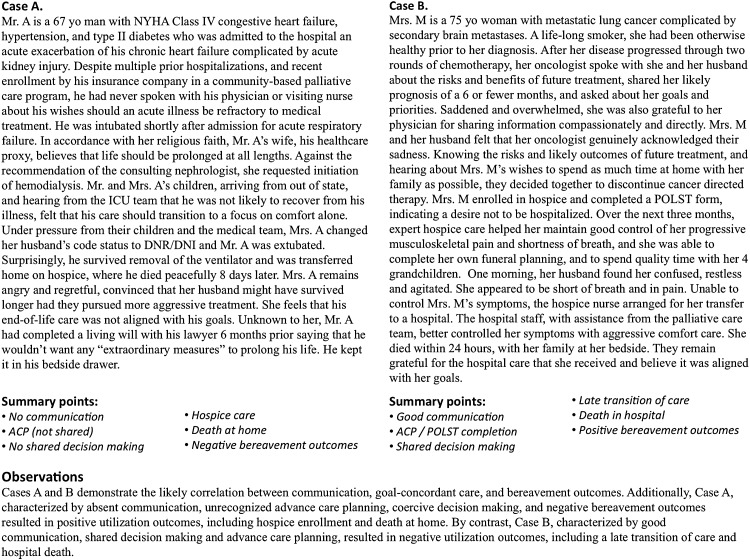

The complexity of measuring the quality of serious illness communication and goal-concordant care cannot be underestimated, and are evident from clinical experience. Figure 1 highlights two prototypical cases that illustrate this complexity. For example, patients like the man in Case A may have several markers of what might be considered high-quality care by traditional measures, but receive care that is perceived as discordant and results in poor bereavement outcomes. The converse, as in Case B, may also be true. Understanding the relationship between communication and goal-concordant care may support quality improvement efforts by identifying the most appropriate targets for quality measurement.

FIG. 1.

Cases illustrating the complexity of quality measurement of communication and goal-concordant care.

A Conceptual Model of the Relationship Between Communication and Goal-Concordant Care

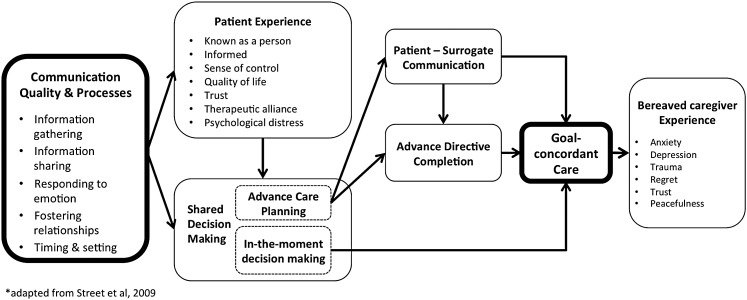

A conceptual model illustrating the relationship between high-quality communication and goal-concordant care (Fig. 2) suggests candidate quality measurement domains. Communication quality in serious illness comprises at least four mutually reinforcing processes: information gathering, information sharing, responding to emotion, and fostering relationships.12 These elements directly shape patient experience and, when done well, help patients feel known, informed, in control, and satisfied, thus improving well-being and quality of life.12–14 Good communication also enhances trust and therapeutic alliance,15–17 which lay the groundwork for SDM.18

FIG. 2.

Clinician–patient communication improves patient and caregiver experience enables shared decision making, and mediates goal-concordant care. Adapted from Street et al.27

SDM may occur in anticipation of future medical decisions during a time of decisional incapacity, known as advance care planning (ACP), or “in the moment,” when there is an immediately relevant decision to be made for a patient with capacity. ACP may result in goal-concordant care indirectly through either patient–surrogate communication and informed surrogate decision making at the time of critical illness, or clinician interpretation of an advance directive (AD).19 By contrast, in-the-moment decision making may lead directly to goal-concordant care.

The receipt of goal-concordant care likely shapes the bereaved caregivers' experience as well. The perception that their loved one received care aligned with their values mitigates anxiety, depression, trauma, and regret, and enhances trust, peacefulness, and satisfaction with care.20 When care is perceived as misaligned, the opposite may be true.

Measuring Communication and Its Outcomes: Challenges and Opportunities

Our model recognizes that multiple factors affect goal-concordant care. Table 2 presents a taxonomy of potential measures that correspond to these factors. Many are supported by evidence, some are currently used as quality indicators, and others are theoretical.

Table 2.

Serious Illness Communication Measures Reflecting Key Domains

| Measure | Source | Description | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Communication processes and quality | |||

| Information gathering | Recorded or documented communication | Assessment of illness understanding; elicitation of patient concerns; exploration of patient goals and priorities | 25,28,90 |

| Information sharing | Delivery of serious news; discussion of prognosis; sharing of risks and benefits | 91,92 | |

| Responding to emotion | Response to emotional cues; empathic statements | 1,26–28,90,93–95 | |

| Fostering relationships | Patient or clinician survey | Patient and clinician description of therapeutic relationship | 25 |

| Global | Patient-reported quality of communication | 35,36 | |

| Communication timing and setting | Claims or administrative data | When and where communication took place | 25 |

| Patient experiencea | |||

| Known | Patient or surrogate survey | Feels known (heard and understood) | 96 |

| Informed | Feels adequately informed about their or loved ones' care | 97,98 | |

| In control | Feels in control of decision making and/or disease trajectory | 46 | |

| Satisfied | Satisfaction with care | 44 | |

| Quality of life | Quality of life | 36,46,99–101 | |

| Trust | Trust in clinician or healthcare system | 102,103 | |

| Therapeutic alliance | A sense of mutual understanding, caring, and trust with their physician | 104 | |

| Shared decision making (inclusive of its direct outcomes) | |||

| Shared decision making | Chart review, recorded or observed communication | Use of tools that promote shared decision making (e.g., best case/worst case, SHARE approach) or documented features of shared decision making | 105–107 |

| Advance directive or POLST completion | Chart review, registry data or patient or surrogate survey | Completion of advance directive, POLST or similar documentation to reflect their preference for future medical treatments | 74,108,109 |

| Family communication | Patient or surrogate survey | Patient reported communicated with family members about their future healthcare goals | 62,110,111 |

| Goal-concordant care | |||

| Patient-reported outcomes | Patient survey | Trust or confidence that future care will be goal concordant | n/a |

| Patient-specific outcomes | Patient, advance directives or POLST registries, claims data | Utilization at the end of life reflects patient or surrogates previously stated or documented care goals (specific or general) or location of death | 21,25,38,75,112–115 |

| Population-specific outcomes • Healthcare utilization • Hospice use • Location of death |

Claims or administrative data | Utilization of given therapies, care settings (including hospice), or location at the end of life; or utilization that may reflect care that is insensitive to patient or family goals and values (e.g., hospice use <3 days or frequent transitions in last days of life) | 76,116–119 |

| Caregiver-reported EOL outcomes | Bereaved caregiver survey | Patient received care in alignment with preferences, whether or not those preferences were known and/or discussed | 62,87,110,120,121 |

| Bereaved caregiver experience | |||

| Quality of care | Bereaved caregiver survey | Quality of care across a number of domains, including symptom control and communication | 21,84,122 |

| Decisional conflict or regret | Decisional conflict or regret related to end-of-life care | 75,123,124 | |

| Quality of life | Quality of life, including depression, anxiety, complicated grief, or post-traumatic symptoms | 125–129 | |

EOL, end of life; n/a, not applicable; POLST, physician's orders for life-sustaining treatment.

Criteria for assessing quality measures include their importance, validity, usability, and feasibility.21 While we believe that these measures meet the threshold of importance, many require further testing for validity, usability, and feasibility. Common measurement challenges include the so-called “denominator problem,”22 that is, uncertainty about which population should be measured, and the timing of measurement—at what points in the disease trajectory or post death should we survey patients or caregivers?

Communication quality and processes

Barriers to collecting and analyzing the content of clinical encounters, through recordings or medical record documentation, impede the goal of directly measuring the quality of communication.23 An audio- or video-recorded medical encounter permits unfiltered analysis of communication content and is thus the measurement gold standard. To date, privacy concerns and logistical complexities have limited recording of communication to research studies.24–30 However, as the boundaries of private and public communication increasingly blur, and personal recording devices proliferate, we might soon easily record all clinical encounters. Advances in natural language processing and machine learning, offer the hope of analyzing recorded encounters at scale.

As an alternative to direct observation, these same technologies also make analysis of electronic health record (EHR) data increasingly feasible.31,32 Currently, EHR documentation poorly approximates actual communication,33 yet health systems can mitigate this challenge by implementing documentation templates that capture key domains of communication. For example, documentation of illness understanding, information preferences, prognostic communication, and patient goals, values, and treatment preferences suggest high-quality communication by recording elements of SDM.18

Survey instruments to assess patients or family members' perspectives on the quality of communication have been used as outcomes in randomized trials, but may be difficult to implement in clinical practice.34–37 The Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS®) surveys and Family Evaluation of Hospice Care measures also assess communication, although in a limited way.38,39 More robust communication-focused instruments could be systematically deployed to seriously ill patients at key inflection points in the serious illness trajectory, including at the time of diagnosis, and enrollment in post-acute and hospice care. Cross-validation of these with direct communication measurements will contribute to our understanding of their respective validity.23

One need not measure communication quality to measure its occurrence. Quality improvement programs, such as the Serious Illness Care Program,24 have demonstrated the feasibility of measuring the timing and setting of communication among seriously ill patients; researchers in Canada have recently validated a set of quality indicators that include communication processes.40

Patient experience

Prospective or retrospective surveys may be used to directly or indirectly assess patient or family experience of communication quality.41–43 Patient ratings of communication and experience overlap conceptually and in practice, but are not the same. Therefore, it is important to assess both. Patient experience measures have driven improvement in care quality by enhancing adherence to recommended treatment processes, and are associated with improved outcomes and patient safety.44,45 Quality of life measures may also reflect patient experience, but most focus predominantly on the physical illness experience, which may respond less to communication.35,46,47 Ideally, clinician–patient communication helps patients feel known as people, informed, and in control of their care, measures of which remain underdeveloped.

Depression and anxiety commonly burden seriously ill patients and their families.48–51 Poor clinician communication can inadvertently contribute to these symptoms and interventions to improve communication have reduced symptoms of depression and anxiety.52,53 Conversely, well-intentioned communication may result in unintended consequences, including increased patient or family distress.36,54,55 For these reasons, a comprehensive assessment of communication outcomes and goal-concordant care should include measurement of anxiety, depression, or complicated grief as markers of the distress that poor communication or goal discordant-care may cause.

Shared decision making

Systematic and expert reviews highlight the difficulties of promoting, participating in, and measuring SDM.56–59 Systems may more feasibly measure the processes and anticipated outcomes of SDM, such as ACP or ACP engagement, than patient perceptions regarding the collaborative nature of their communication experience.60 Studies measuring ACP processes demonstrate mixed outcomes. For example, the Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments (SUPPORT) study showed no meaningful improvements in care among patients randomized to an intervention that included ACP.61 However, the Respecting Choices model of ACP has been shown to decrease hospitalizations and to improve caregiver awareness of patient wishes and perceived goal-concordant care.62,63

Patient–surrogate communication

Measuring patient–surrogate communication also carries benefit.24 First, uninformed surrogates complicate end-of-life decision making. Second, surrogates commonly assess patient's wishes incorrectly and apply them inconsistently; neither surrogate assignment nor prior discussion of patient treatment preferences improve alignment on treatment choices in hypothetical scenarios.64 Finally, patients vary in how much leeway they wish to give surrogates, with some deferring to surrogates even when decisions contradict previously stated preferences.65 Furthermore, factors unrelated to clinician–patient communication (such as the patient–surrogate relationship) determine patient–surrogate communication. Despite these complexities, measuring patient–surrogate communication may facilitate quality improvement efforts to improve surrogate understanding of patient's wishes and may address gaps in our understanding of the mechanism by which ACP results in goal-concordant care.

AD completion

Several quality frameworks support documentation of treatment preferences in an AD.9,66,67 However, AD completion remains a problematic quality indicator for several reasons. First, ADs do not always reflect SDM.68–70 Second, patients' preferences may change as their illness progresses making previously completed AD no longer accurate.71,72 Third, ADs inconsistently demonstrate their impact on the delivery of goal-concordant care, with a majority of studies showing little association between the two.73 Finally, limited portability and inconsistent interpretation by family and clinicians limit implementation of ADs.70,73 Legal documents, such as living wills, are not universally accessible. Portable medical orders, such as Physician's Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) or Medical Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (MOLST), have been shown to influence location of death in accordance with stated preferences,74 but patient selection remains unclear and some have raised concerns about their interpretability and degree of patient centeredness.75 Because they are increasingly utilized and will remain part of the complex landscape of serious illness care,76 we should measure their completion and impact on goal-concordant care.

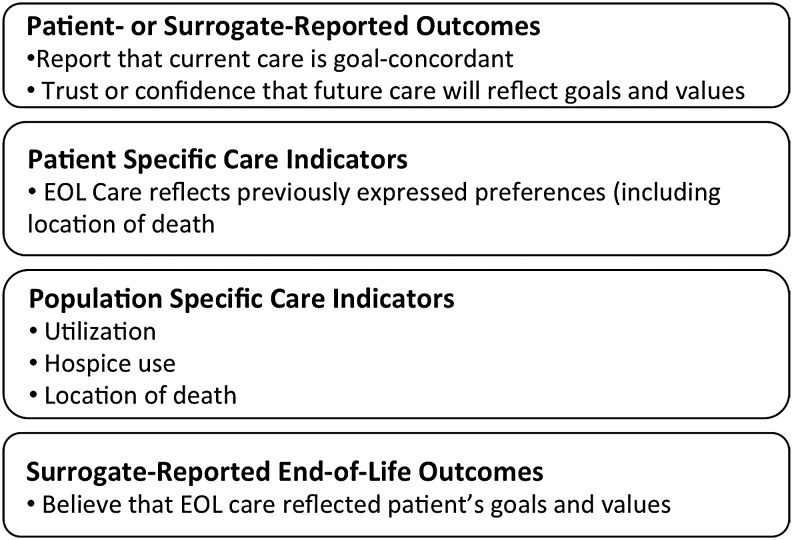

Goal-concordant care

Healthcare systems can assess goal-concordant care in four ways (Fig. 3): (1) patient- or surrogate-reported outcomes of goal-concordant care, (2) patient-specific care indicators, (3) population-specific care indicators, and (4) bereaved caregiver reports of whether end-of-life care was goal concordant.

FIG. 3.

Measurement domains for goal-concordant care.

While not widely used, patient-reported assessments of goal-concordant care present an opportunity to measure goal-concordant care before death. The SUPPORT investigators measured goal-concordant care by assessing agreement between patient preference for care focused on life extension or comfort, and patient assessment of whether or not current care aligned with that preference.61 Patients frequently value conflicting or contingent goals equally,77 making such a “forced choice” to some degree a false one. However, it may help clarify a patient's highest priority, and whether or not a health system helps meet it. There may be other ways to prospectively assess goal-concordant care, including a single-item measure to assess confidence that a patient's current or future care aligns, or will align, with their goals and values.

Patient-specific outcomes compare a known preference, usually communicated through an AD or portable medical order, and an end-of-life outcome, including care utilization or location of death. Uncertainty about the timing of preference measurement and methodological constraints related to identifying deceased patients and collecting utilization data from multiple settings complicate these approaches. Additionally, patients may provide general guidance for care that may not easily translate into specific care options.

Population-specific outcomes include trends in healthcare utilization over time and location of deaths.78,79 Comparison to survey data about care preferences may suggest a population-level goal concordance of care.80 Such measures may help shape policy, and a recent study suggests that they may be meaningful for individuals, as less hospital care and more hospice care relate to higher caregiver-reported EOL care-quality outcomes.20

Measuring bereaved caregiver's perceptions regarding the goal concordance of their loved one's end-of-life care remains an untapped domain of quality assessment. While surrogates commonly predict patient's wishes inaccurately in hypothetical scenarios,64 their shared experience with the dying patient may be the closest thing we have to the patient's own voice.81 Because preferences can change as illness progresses, surrogates' beliefs about patient's goals may be more accurate than those previously recorded by patients. A recent study found that, when compared with caregivers who reported goal-concordant care, those reporting goal-discordant care rated the quality of communication and quality of care lower.82 Limitations of this approach include the potential for multiple biases83–85 and challenges identifying surrogates. However, the Veterans Affairs administration's Bereaved Family Survey86 and several mortality follow-back studies have demonstrated the feasibility of this approach.87–89

Bereaved caregiver experience

Finally, measuring the bereaved caregiver's experience represents an important quality measurement opportunity. When patients die, their loved ones are left to grieve, cope, and reconsider the care that took place over the patient's illness trajectory. Healthcare resulting in bereaved caregivers feeling more anxious, depressed, traumatized, or regretful may reflect poor-quality EOL care and communication.90,91 We do not know if a lack of perceived goal concordance predicts complicated grief, or other negative outcomes, but such a relationship is plausible and should be investigated.

Recommendations

The cases in Figure 1 demonstrate the likely correlation between communication, goal-concordant care, and bereavement outcomes. The measurement challenges illustrated by these scenarios inform our recommendations for quality measures that should be implemented now in the care of seriously ill patients, and recommendations for the future. Specifically, they illustrate the need for specific goal-concordant care measures.

Implementation-ready measures

Three quality indicators appear ready for implementation in cohorts of seriously ill patients: (1) timing and setting of serious illness communication; (2) patient (or surrogate) experience of communication and care; and (3) caregiver bereavement surveys that include assessment of perceived goal concordance of end-of-life care.

First, we advocate for measurement of when, where, and with whom communication happens, because it has the potential to drive improvement in the frequency, timing, and quality of communication. Communication is a prerequisite for delivering goal-concordant care, and sufficient evidence exists to suggest the benefit of timely, high-quality communication. Measuring this process is likely to have greater impact than measurement of AD completion alone.

Second, measurement of patient experience of communication and care will reflect the quality of communication and serious illness care as a whole. Some patient experience measures remain underdeveloped; others, including quality of life are valid, reliable, and meaningful.

Third, we advocate measurement of goal-concordant care through caregiver bereavement surveys, specifically by asking questions to assess whether caregivers believe that their loved one received care consistent with their values and preferences.

Future measurement candidates

We recommend prioritizing three quality indicators for further development: communication quality, prospective patient or family assessment of goal-concordant care, and the bereaved caregiver experience. First, applying existing tools and technology to the direct measurement of communication remains limited by data access and privacy concerns. These obstacles are surmountable. Doing so could revolutionize serious illness care by placing the clinician–patient communication in a position that reflects its primacy in patients' illness experiences. Second, prospectively assessing patient or surrogate-reported goal-concordant care may present real-time opportunities to improve communication and care. Preliminary findings from ongoing studies suggest that this outcome may be responsive to communication interventions. Third, attending to bereaved caregivers' experiences will shape our understanding and delivery of serious illness care. Some aspects of their experience may reflect neither communication quality nor goal-concordant care. The experience of the bereaved matters. If the deceased could speak, this would likely be the thing that many would say matters most.

The proposed quality measures highlight research priorities in serious illness communication, particularly as we consider their applicability to accountability programs. We must understand the responsiveness of these measures to interventions; assess at multiple time points the relationship between current, prospective, and retrospective reports of goal-concordant care and actual care outcomes; and assess the relationships between and relative impact of clinician–patient communication on patient–surrogate communication, AD completion, and goal-concordant care.

Conclusion

As we consider opportunities for systematic quality measurement in seriously ill patients, we advocate for ensuring that communication has occurred, and for measuring its impact. The most important outcomes of communication, and indeed all of serious illness care, are the patient experience and the receipt of goal-concordant care. We have the tools to measure both.

Future research can address knowledge gaps. Yet, the lack of complete data should not stop implementation in the short term. Negative patient experiences and the delivery of goal-discordant care currently cause harm to patients and families. Our intolerance of these outcomes must be matched by our willingness to measure them.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, Cambia Health Foundation, and Joanna Paladino, MD.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Pollak KI, Arnold RM, Jeffreys AS, et al. : Oncologist communication about emotion during visits with patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:5748–5752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelley A: Consensus definition for Gordon & Betty Moore Foundation-funded symposium on quality measurement in community based serious illness programs. J Palliat Med 2017;20 Supp2:XXX–XXX [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bambauer KZ, Zhang B, Maciejewski PK, et al. : Mutuality and specificity of mental disorders in advanced cancer patients and caregivers. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2006;41:819–824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mullainathan S, Shafir E: Scarcity: Why Having Too Little Means so Much, 1st edn. New York: Times Books, Henry Holt and Company, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Institute of Medicine: To Err is Human; Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Institute of Medicine: Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Legare F: Shared decision making: Moving from theorization to applied research and hopefully to clinical practice. Patient Educ Couns 2013;91:129–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dy SM, Kiley KB, Ast K, et al. : Measuring what matters: Top-ranked quality indicators for hospice and palliative care from the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine and Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;49:773–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guiding Principles [press release]: www.thectac.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/C-TAC-Guiding-Principles-UPDATED.pdf2014 (last accessed May12, 2017)

- 10.Lorenz KA, Rosenfeld K, Wenger N: Quality indicators for palliative and end-of-life care in vulnerable elders. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55 Suppl 2:S318–S326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Unroe KT, Hickman SE, Torke AM, Group ARCW: Care consistency with documented care preferences: Methodologic considerations for implementing the “measuring what matters” quality indicator. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016;52:453–458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Street RL, Jr., Makoul G, Arora NK, Epstein RM: How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Educ Couns 2009;74:295–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Medendorp NM, Visser LN, Hillen MA, et al. : How oncologists' communication improves (analogue) patients' recall of information. A randomized video-vignettes study. Patient Educ Couns 2017;100:1338–1344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murray CD, McDonald C, Atkin H: The communication experiences of patients with palliative care needs: A systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative findings. Palliat Support Care 2015;13:369–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Epstein R, Street RL: Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: Promoting Healing and Reducing Suffering. Bethsda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huff NG, Nadig N, Ford DW, Cox CE: Therapeutic alliance between the caregivers of critical illness survivors and intensive care unit clinicians. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2015;12:1646–1653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hillen MA, de Haes HC, Stalpers LJ, et al. : How can communication by oncologists enhance patients' trust? An experimental study. Ann Oncol 2014;25:896–901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Legare F, Witteman HO: Shared decision making: Examining key elements and barriers to adoption into routine clinical practice. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:276–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sudore RL, Lum HD, You JJ, et al. : Defining advance care planning for adults: A consensus definition from a multidisciplinary Delphi panel. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017;53:821–832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wright AA, Keating NL, Ayanian JZ, et al. : Family perspectives on aggressive cancer care near the end of life. JAMA 2016;315:284–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seow H, Snyder CF, Mularski RA, et al. : A framework for assessing quality indicators for cancer care at the end of life. J Pain Symptom Manage 2009;38:903–912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teno JM, Coppola KM: For every numerator, you need a denominator: A simple statement but key to measuring the quality of care of the “dying”. J Pain Symptom Manage 1999;17:109–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tulsky JA, Beach MC, Butow PN, et al. : Research agenda for communication in serious illness: A review. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:1361–1366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bernacki R, Hutchings M, Vick J, et al. : Development of the Serious Illness Care Program: A randomised controlled trial of a palliative care communication intervention. BMJ Open 2015;5:e009032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roter D, Larson S: The Roter interaction analysis system (RIAS): Utility and flexibility for analysis of medical interactions. Patient Educ Couns 2002;46:243–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ford S, Hall A, Ratcliffe D, Fallowfield L: The Medical Interaction Process System (MIPS): An instrument for analysing interviews of oncologists and patients with cancer. Soc Sci Med 2000;50:553–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Street RL, Jr., Millay B: Analyzing patient participation in medical encounters. Health Commun 2001;13:61–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tulsky JA, Fischer GS, Rose MR, Arnold RM: Opening the black box: How do physicians communicate about advance directives? Ann Intern Med 1998;129:441–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stapleton RD, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, et al. : Clinician statements and family satisfaction with family conferences in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2006;34:1679–1685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Selph RB, Shiang J, Engelberg R, et al. : Empathy and life support decisions in intensive care units. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:1311–1317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Friedman C, Rindflesch TC, Corn M: Natural language processing: State of the art and prospects for significant progress, a workshop sponsored by the National Library of Medicine. J Biomed Inform 2013;46:765–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kreimeyer K, Foster M, Pandey A, et al. : Natural language processing systems for capturing and standardizing unstructured clinical information: A systematic review. J Biomed Inform 2017;46:765–773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Solet DJ, Norvell JM, Rutan GH, Frankel RM: Lost in translation: Challenges and opportunities in physician-to-physician communication during patient handoffs. Acad Med 2005;80:1094–1099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Engelberg R, Downey L, Curtis JR: Psychometric characteristics of a quality of communication questionnaire assessing communication about end-of-life care. J Palliat Med 2006;9:1086–1098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hearn J, Higginson IJ: Development and validation of a core outcome measure for palliative care: The palliative care outcome scale. Palliative Care Core Audit Project Advisory Group. Qual Health Care 1999;8:219–227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Curtis JR, Back AL, Ford DW, et al. : Effect of communication skills training for residents and nurse practitioners on quality of communication with patients with serious illness: A randomized trial. JAMA 2013;310:2271–2281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hanson LC, Zimmerman S, Song MK, et al. : Effect of the goals of care intervention for advanced dementia: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:24–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Consumer Asessment of Healthcare Providers & Systems (CAHPS®). Available at https://www.ahrq.gov/cahps/index.html (last accessed May12, 2017)

- 39.Connor SR, Teno J, Spence C, Smith N: Family evaluation of hospice care: Results from voluntary submission of data via website. J Pain Symptom Manage 2005;30:9–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heyland DK, Dodek P, You JJ, et al. : Validation of quality indicators for end-of-life communication: Results of a multicentre survey. CMAJ 2017;189:E980–E989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sulmasy DP, McIlvane JM, Pasley PM, Rahn M: A scale for measuring patient perceptions of the quality of end-of-life care and satisfaction with treatment: The reliability and validity of QUEST. J Pain Symptom Manage 2002;23:458–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Teno JM, Clarridge B, Casey V, et al. : Validation of toolkit after-death bereaved family member interview. J Pain Symptom Manage 2001;22:752–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Casarett D, Shreve S, Luhrs C, et al. : Measuring families' perceptions of care across a health care system: Preliminary experience with the Family Assessment of Treatment at End of Life Short form (FATE-S). J Pain Symptom Manage 2010;40:801–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dy SM, Shugarman LR, Lorenz KA, et al. : A systematic review of satisfaction with care at the end of life. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:124–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anhang Price R, Elliott MN, Zaslavsky AM, et al. : Examining the role of patient experience surveys in measuring health care quality. Med Care Res Rev 2014;71:522–554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cohen SR, Mount BM, Strobel MG, Bui F: The McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire: A measure of quality of life appropriate for people with advanced disease. A preliminary study of validity and acceptability. Palliat Med 1995;9:207–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hui D, Bruera E: The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System 25 years later: Past, present, and future developments. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017;53:630–643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilson KG, Chochinov HM, Skirko MG, et al. : Depression and anxiety disorders in palliative cancer care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007;33:118–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Woo JA, Maytal G, Stern TA: Clinical challenges to the delivery of end-of-life care. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2006;8:367–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Siegel MD, Hayes E, Vanderwerker LC, et al. : Psychiatric illness in the next of kin of patients who die in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2008;36:1722–1728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, et al. : Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:987–994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tilden VP, Tolle SW, Garland MJ, Nelson CA: Decisions about life-sustaining treatment. Impact of physicians' behaviors on the family. Arch Intern Med 1995;155:633–638 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B, et al. : A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. N Engl J Med 2007;356:469–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Cronin A, et al. : Patients' expectations about effects of chemotherapy for advanced cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1616–1625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Carson SS, Cox CE, Wallenstein S, et al. : Effect of palliative care-led meetings for families of patients with chronic critical illness: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016;316:51–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sepucha KR, Borkhoff CM, Lally J, et al. : Establishing the effectiveness of patient decision aids: Key constructs and measurement instruments. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2013;13 Suppl 2:S12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Austin CA, Mohottige D, Sudore RL, et al. : Tools to promote shared decision making in serious illness: A systematic review. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:1213–1221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jones J, Nowels C, Kutner JS, Matlock DD: Shared decision making and the use of a patient decision aid in advanced serious illness: Provider and patient perspectives. Health Expect 2015;18:3236–3247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Joseph-Williams N, Elwyn G, Edwards A: Knowledge is not power for patients: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of patient-reported barriers and facilitators to shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns 2014;94:291–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sudore RL, Heyland DK, Barnes DE, et al. : Measuring advance care planning: Optimizing the advance care planning engagement survey. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017;53:669–681.e668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients: The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT). The SUPPORT Principal Investigators. JAMA 1995;274:1591–1598 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, Silvester W: The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010;340:c1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rocque GB, Dionne-Odom JN, Sylvia Huang CH, et al. : Implementation and impact of patient lay navigator-led advance care planning conversations. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017;53:682–692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shalowitz DI, Garrett-Mayer E, Wendler D: The accuracy of surrogate decision makers: A systematic review. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:493–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rid A, Wesley R, Pavlick M, et al. : Patients' priorities for treatment decision making during periods of incapacity: Quantitative survey. Palliat Support Care 2015;13:1165–1183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care: www.nationalconsensusproject.org (Last accessed March15, 2017)

- 67.Measuring What Matters: www.aahpm.org/quality/measuring-what-matters (Last accessed March15, 2017)

- 68.Sudore RL, Fried TR: Redefining the “planning” in advance care planning: Preparing for end-of-life decision making. Ann Intern Med 2010;153:256–261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McMahan RD, Knight SJ, Fried TR, Sudore RL: Advance care planning beyond advance directives: Perspectives from patients and surrogates. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013;46:355–365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Perkins HS: Controlling death: The false promise of advance directives. Ann Intern Med 2007;147:51–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Auriemma CL, Nguyen CA, Bronheim R, et al. : Stability of end-of-life preferences: A systematic review of the evidence. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:1085–1092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.White MT: Uncharted terrain: Preference construction at the end of life. J Clin Ethics 2014;25:120–130 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Moore KA, Rubin EB, Halpern SD: The problems with physician orders for life-sustaining treatment. JAMA 2016;315:259–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fromme EK, Zive D, Schmidt TA, et al. : Association between physician orders for life-sustaining treatment for scope of treatment and in-hospital death in Oregon. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014;62:1246–1251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Halpern SD: Toward evidence-based end-of-life care. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2001–2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tolle SW, Teno JM: Lessons from Oregon in embracing complexity in end-of-life care. N Engl J Med 2017;376:1078–1082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Heyland DK, Heyland R, Dodek P, et al. : Discordance between patient's stated values and treatment preferneces for end-of-life care: Results of a multicentre trial. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2017;7:292–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Teno JM, Gozalo PL, Bynum JP, et al. : Change in end-of-life care for Medicare beneficiaries: Site of death, place of care, and health care transitions in 2000, 2005, and 2009. JAMA 2013;309:470–477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Addington-Hall JM, O'Callaghan AC: A comparison of the quality of care provided to cancer patients in the UK in the last three months of life in in-patient hospices compared with hospitals, from the perspective of bereaved relatives: Results from a survey using the VOICES questionnaire. Palliat Med 2009;23:190–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Goodman DC, Fisher ES, Wennberg JE, et al. : Tracking Improvements in the Care of Chronically Ill Patients: A Dartmouth Atlas Brief on Medicare Beneficiaries Near the End of Life. The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy & Clinical Practice, June 12, 2013, 2013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.McPherson CJ, Addington-Hall JM: Judging the quality of care at the end of life: Can proxies provide reliable information? Soc Sci Med 2003;56:95–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Khandelwal N, Curtis JR, Freedman VA, et al. : How often is end-of-life care in the United States inconsistent with patients' goals of care? J Palliat Med 2017. [Epub ahead of print; DOI: 10.1089/jpm.2017.0065.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Walker WR, Vogl RJ, Thompson CP: Autobiographical memory: unpleasantness fades faster than pleasantness over time. Appl Cogn Psychol 1997;11:399–413 [Google Scholar]

- 84.Higginson I, Priest P, McCarthy M: Are bereaved family members a valid proxy for a patient's assessment of dying? Soc Sci Med 1994;38:553–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Addington-Hall J, McPherson C: After-death interviews with surrogates/bereaved family members: Some issues of validity. J Pain Symptom Manage 2001;22:784–790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ersek M, Smith D, Cannuscio C, et al. : A nationwide study comparing end-of-life care for men and women veterans. J Palliat Med 2013;16:734–740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Burge F, Lawson B, Johnston G, et al. : Bereaved family member perceptions of patient-focused family-centred care during the last 30 days of life using a mortality follow-back survey: Does location matter? BMC Palliat Care 2014;13:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lawson B, Van Aarsen K, Burge F: Challenges and strategies in the administration of a population based mortality follow-back survey design. BMC Palliat Care 2013;12:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Teno JM, Freedman VA, Kasper JD, et al. : Is care for the dying improving in the United States? J Palliat Med 2015;18:662–666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Miyajima K, Fujisawa D, Yoshimura K, et al. : Association between quality of end-of-life care and possible complicated grief among bereaved family members. J Palliat Med 2014;17:1025–1031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Krug K, Miksch A, Peters-Klimm F, et al. : Correlation between patient quality of life in palliative care and burden of their family caregivers: A prospective observational cohort study. BMC Palliat Care 2016;15:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fallowfield L, Jenkins V, Farewell V, et al. : Efficacy of a cancer research UK communication skills training model for oncologists: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2002;359:650–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hagerty RG, Butow PN, Ellis PA, et al. : Cancer patient preferences for communication of prognosis in the metastatic setting. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:1721–1730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gattellari M, Voigt KJ, Butow PN, Tattersall MH: When the treatment goal is not cure: Are cancer patients equipped to make informed decisions? J Clin Oncol 2002;20:503–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pollak KI, Alexander SC, Tulsky JA, et al. : Physician empathy and listening: Associations with patient satisfaction and autonomy. J Am Board Fam Med 2011;24:665–672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tulsky JA, Arnold RM, Alexander SC, et al. : Enhancing communication between oncologists and patients with a computer-based training program: A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:593–601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zimmermann C, Del Piccolo L, Bensing J, et al. : Coding patient emotional cues and concerns in medical consultations: The Verona coding definitions of emotional sequences (VR-CoDES). Patient Educ Couns 2011;82:141–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gramling R, Stanek S, Ladwig S, et al. : Feeling heard and understood: A patient-reported quality measure for the inpatient palliative care setting. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016;51:150–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sepucha KR, Fagerlin A, Couper MP, et al. : How does feeling informed relate to being informed? The DECISIONS survey. Med Decis Making 2010;30(5 Suppl):77S–84S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Smets EM, Hillen MA, Douma KF, et al. : Does being informed and feeling informed affect patients' trust in their radiation oncologist? Patient Educ Couns 2013;90:330–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Steinhauser KE, Clipp EC, Bosworth HB, et al. : Measuring quality of life at the end of life: Validation of the QUAL-E. Palliat Support Care 2004;2:3–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, et al. : The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: Development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol 1993;11:570–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mularski RA, Dy SM, Shugarman LR, et al. : A systematic review of measures of end-of-life care and its outcomes. Health Serv Res 2007;42:1848–1870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Shea JA, Micco E, Dean LT, et al. : Development of a revised Health Care System Distrust scale. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:727–732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Leisen B, Hyman MR: An improved scale for assessing patients' trust in their physician. Health Mark Q 2001;19:23–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mack JW, Block SD, Nilsson M, et al. : Measuring therapeutic alliance between oncologists and patients with advanced cancer: The Human Connection Scale. Cancer 2009;115:3302–3311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Taylor LJ, Nabozny MJ, Steffens NM, et al. : A framework to improve surgeon communication in high-stakes surgical decisions: Best case/worst case. JAMA Surg 2017;152:531–538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.AHRQ: The SHARE Approach: Essential Steps of Shared Decision Making: Expanded Reference Guide iwth Sample Conversation Starters (Workshop Curriculum: Tool 2). 2014. www.ahrq.gov/shareddecisionmaking (Last accessed March20, 2017)

- 109.Elwyn G, Hutchings H, Edwards A, et al. : The OPTION scale: Measuring the extent that clinicians involve patients in decision-making tasks. Health Expect 2005;8:34–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zive DM, Fromme EK, Schmidt TA, et al. : Timing of POLST form completion by cause of death. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;50:650–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Schenck AP, Rokoske FS, Durham D, et al. : Quality measures for hospice and palliative care: Piloting the PEACE measures. J Palliat Med 2014;17:769–775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Johnson S, Clayton J, Butow PN, et al. : Advance care planning in patients with incurable cancer: Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2016;6:e012387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.National Health and Aging Trends Study: www.nhats.org (Last accessed March20, 2017)

- 114.Biola H, Sloane PD, Williams CS, et al. : Preferences versus practice: Life-sustaining treatments in last months of life in long-term care. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2010;11:42–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Silveira MJ, Kim SY, Langa KM: Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1211–1218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Winkler EC, Reiter-Theil S, Lange-Riess D, et al. : Patient involvement in decisions to limit treatment: The crucial role of agreement between physician and patient. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:2225–2230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Mack JW, Weeks JC, Wright AA, et al. : End-of-life discussions, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: Predictors and outcomes of receipt of care consistent with preferences. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:1203–1208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wilson DM, Shen Y, Birch S: New evidence on end-of-life hospital utilization for enhanced health policy and services planning. J Palliat Med 2017;20:752–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Bekelman JE, Halpern SD, Blankart CR, et al. : Comparison of site of death, health care utilization, and hospital expenditures for patients dying with cancer in 7 developed countries. JAMA 2016;315:272–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Gao W, Ho YK, Verne J, et al. : Changing patterns in place of cancer death in England: A population-based study. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Pivodic L, Pardon K, Morin L, et al. : Place of death in the population dying from diseases indicative of palliative care need: A cross-national population-level study in 14 countries. J Epidemiol Community Health 2016;70:17–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Pasman HR, Kaspers PJ, Deeg DJ, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD: Preferences and actual treatment of older adults at the end of life. A mortality follow-back study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013;61:1722–1729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Teno JM, Clarridge BR, Casey V, et al. : Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of care. JAMA 2004;291:88–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Kumar P, Wright AA, Hatfield LA, et al. : Family perspectives on hospice care experiences of patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:432–439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Smith-Howell ER, Hickman SE, Meghani SH, et al. : End-of-life decision making and communication of bereaved family members of African Americans with serious illness. J Palliat Med 2016;19:174–182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Brehaut JC, O'Connor AM, Wood TJ, et al. : Validation of a decision regret scale. Med Decis Making 2003;23:281–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Steinhauser KE, Voils CI, Bosworth HB, Tulsky JA: Validation of a measure of family experience of patients with serious illness: The QUAL-E (Fam). J Pain Symptom Manage 2014;48:1168–1181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Creamer M, Bell R, Failla S: Psychometric properties of the Impact of Event Scale—Revised. Behav Res Ther 2003;41:1489–1496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK, Reynolds CF, 3rd, et al. : Inventory of Complicated Grief: A scale to measure maladaptive symptoms of loss. Psychiatry Res 1995;59:65–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]