Abstract

Background: Palliative care offers an approach to the care of people with serious illness that focuses on quality of life and aligning care with individual and family goals, and values in the context of what is medically achievable.

Objective: Measurement of the impact of palliative care is critical for determining what works for which patients in what settings, to learn, improve care, and ensure access to high value care for people with serious illness.

Methods: A learning health system that includes patients and families partnering with clinicians and care teams, is directly linked to a registry to support networks for improvement and research, and offers an ideal framework for measuring what matters to a range of stakeholders interested in improving care for this population.

Measurements: Measurement focuses on the individual patient and family experience as the fundamental outcome of interest around which all care delivery is organized.

Results: We describe an approach to codesigning and implementing a palliative care registry that functions as a learning health system, by combining patient and family inputs and clinical data to support person-centered care, quality improvement, accountability, transparency, and scientific research.

Discussion: The potential for a palliative care learning health system that, by design, brings together enriched information environments to support coproduction of healthcare and facilitated peer networks to support patients and families, collaborative clinician networks to support palliative care program improvement, and collaboratories to support research and the application of research to benefit individual patients is immense.

Keywords: : coproduction, learning health system, palliative care, registry

If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together. A Masai Proverb

Introduction: A Call for a Collaborative Learning Health System in Palliative Care

Healthcare for persons with serious illness in the United States often fails to meet the priorities and needs of patients and families, resulting in suffering, preventable crises, and high use of emergency services.1,2 Palliative care focuses on quality of life and aligning care with individual goals and values in the context of what is medically achievable. Because palliative care interventions match service delivery to the needs and goals of patients and families, quality improves and costly crises and emergencies are often prevented, leading to a higher value of healthcare.

There is increasing awareness across the healthcare system of the necessity of measuring the impact of care that is delivered. Measurement is especially critical in palliative care to determine what works for whom in what settings to improve and ensure access to high value care for people with the most serious illness. Recognizing the need to “measure what matters”3 has led several groups to develop innovative palliative care registries to (1) assess prevalence and quality; (2) enable peer to peer comparisons4; (3) establish research networks to advance science5; and (4) develop community-based collaborative improvement networks to make measurable advances in palliative care quality across geographically diverse settings based on benchmarking, transparency, and sharing effective practices.5,6

There is an opportunity to achieve more by integrating these registries into a single system using two powerful conceptual frameworks to achieve multiple goals. The first framework—the learning health system—was popularized by the Institute of Medicine. “A learning health system … generates and applies the best evidence for the collaborative health care choices of each patient and provider … (and) drives the process of discovery as a natural outgrowth of patient care.”7 The second framework—service coproduction—was developed by thought leaders outside of healthcare, including Fuchs,8 Normann and Ramirez,9 Toffler,10 and Ostrom.11 Essential insights from the coproduction model are that when consumers and providers of services actually work together, they produce value8 and coproduced services are often more attractive, efficient, and sustainable.12

Collaborative design and delivery of care more fully engages healthcare teams, patients, and families, and is associated with a shift from an exclusive focus on disease treatment to expanded attention to the patient's priorities, concerns, and goals.13 Because palliative care's focus includes the psychological, social, emotional, and spiritual well-being of both the patient and family, it is ideally suited for coproduction.

Registry creation for palliative care fits naturally together with the learning health system and coproduction frameworks. Drawing on the experience of others and taking into account the unique aspects of palliative care practice, including the inherent heterogeneity of serious illnesses and range of settings where care is delivered, this report describes developing a single palliative care registry that combines patient and family inputs and clinical data to support person-centered care, quality improvement, and scientific research. The design and implementation of such a registry use coproduction principles to bring together patients and families, clinicians and care teams, and researchers to form a sustainable partnership—a collaboratory—for coproducing health and well-being, continuous improvement of care, and research to support learning and guide future investment and practice.14

The Learning Health System Coproduction Model

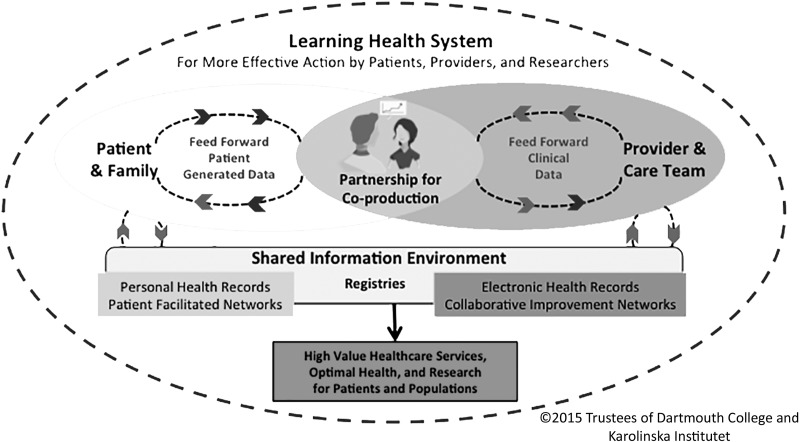

At the heart of the learning health system coproduction model is a partnership between the patient and family, and the care team. Individualized care pathways produce optimal health and well-being (as defined by the person and family) for individuals and, ultimately, for populations.15 Coproduction relies on an enriched information environment that includes “feed forward” patient generated data available to clinicians in real time along with clinical/biomedical data to provide an ongoing record of the person's subjective and objective health status and associated treatments (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

A patient-centered, registry-based learning health system.

This information environment not only allows creation of a patient- and provider-facing dashboard that can be used in real time during care delivery but also serves as a repository of data that can be reused for other purposes, including the following: (1) outcomes research; (2) collaborative clinical improvement networks; (3) facilitated and curated patient networks; and (4) generation of comparative, case-mix adjusted quality and performance reports that can—with proper safeguards for privacy and confidentiality—be shared with clinicians, patients, payers, governmental programs (e.g., Medicare), accreditors (e.g., The Joint Commission), and the public.

The conceptual model is designed as a comprehensive system comprising four inter-related subsystems: (1) the person/family and clinician/care team service delivery system; (2) the patient-/family-facilitated network system; (3) the research collaboratory system; and (4) the collaborative improvement network system. What holds the subsystems together is a set of shared aims, including optimizing the health and well-being of persons and families, continuously improving the value of healthcare service delivery, and building scientific knowledge to measurably improve health outcomes, clinical effectiveness, and value.16

Care models developed in conjunction with patients and families using the learning health system coproduction approach have led to improvements in the outcomes and experiences of patients with rheumatological conditions,17 inflammatory bowel disease,18 and cystic fibrosis.19

Creation of a Registry-Based Learning Health System for Palliative Care

Developing a palliative care registry-based learning health system could proceed in four phases, drawing on principles that come from diverse fields, including service design,20 improvement science,21 change management,22 agile software development,23 and service coproduction.13,24

Ready! Assemble a codesign team, pausing to clarify aims

First, convene an interdisciplinary design team that includes persons with serious illness and their families, clinicians, and care teams (both palliative care and others who care for people with serious illness), community resource staff, researchers, and IT design experts to develop a set of shared aims. The group starts by asking, “What needs must be met?” Through a series of discussions, the group develops a shared understanding first of key patient and family needs and then the needs of other stakeholders. This foundational work defines principles that will guide the learning health system and inform registry development.

On your mark! Learn from what others have already done

The codesign team then learns from what has already been accomplished. Three steps are important:

• Scan the environment to create an inventory of relevant registries

• Learn from others: Study successful pioneering efforts to establish sustainable learning health systems such as the Swedish Rheumatology Quality Registry25 and Live for Life [also in Sweden]26; and in the United States, ImproveCareNow,27 and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry.28 Ask questions such as “What worked well?” “What did not work?” “Which aspects are directly applicable to palliative care?” “What adaptations are needed?”

• Learn from ourselves: It is imperative to learn from the achievements of existing palliative care national registries: the National Palliative Care Registry™ (the Registry), the Palliative Care Quality Network (PCQN), the Global Palliative Care Quality Alliance and its data collection system, and the Quality Data Collection Tool (QDACT). These exemplary initiatives (see Appendix 1, which is available at www.liebertpub.com/jpm) are as follows: “complementary systems for reporting on and improving palliative care services in the United States. The Registry is a broad-reaching, annual, aggregate data reporting platform profiling palliative care teams and their programmatic activities. It does not include patient-level outcomes. In contrast, QDACT focuses on real-time data entry at the point of care and clinician feedback on clinical quality outcomes and national quality standards, while the PCQN also enables real-time clinical data entry, benchmarking, peer comparison, and quality improvement networks.”29 None of the existing U.S.-based palliative care registries yet allow for direct input of data by patients and family caregivers. Drawing on the experiences of representatives of these registries to understand what has worked well and what they would change, add, or remove from their respective systems will help ensure that the next generation of learning health system builds on the best features of the current ones.

Get set! Tailor the general model to the palliative care context

As the codesign team moves closer to creating its learning health system model, key tasks include considering unique aspects of palliative care practice that should guide the process, as well as beginning to imagine the future that the learning health system will bring about.

• Consider context: Table 1 highlights some factors that should be considered in adapting the learning health system model to fit the palliative care context.

• Imagine the future: Based on successful, real-world demonstrations of registry-based learning health systems in the United States and in Sweden, we can begin to develop a vision of the future, imagining the benefits of such a system in palliative care, such as15 the following:

○ Focus on the individual patient and family experience as the fundamental outcome of interest around which all care delivery is organized.30

○ A system designed to be sensitive to changes in patient needs and priorities as the disease progresses, affecting symptoms, function, caregiver burden, and nature of the person's hopes and concerns

○ Digital collection and use of both clinical and patient- or caregiver-reported information both to guide treatment plans and as a basis for improvement, research, and health policy

○ Access to the system for all healthcare teams involved in the comanagement of palliative care patients to facilitate care coordination and information sharing

○ Shared power and responsibility among all stakeholders for designing, governing, and evaluating services, improvement, and research

○ Measurable improvements in individual and population experience of illness and care through (1) improving the alignment of care with each individual's priorities and preferences; (2) application of evidence-based practices; and (3) conduct of rigorous trials (including N of 1 trials) of new approaches to add to the knowledge base

○ Dissemination and translation of ideas and findings through publication of articles in peer-reviewed journals; networks as described above; and outreach to patients, families, clinicians, researchers, policy makers, and payers

• Adapt the model: Craft an idealized design31 that illustrates and specifies how the four subsystems that comprise the whole of a learning health system fit for the future of palliative care.

○ Individual person-centered networks that work together across settings to cocreate daily care that is responsive to changing priorities and the evolving trajectory of illness

○ Facilitated social networks linking patients, families, and caregivers32 that encourage them to engage directly in their own healthcare/social care and are supported by information and tools to track and support daily care, functioning, and well-being

○ A collaborative national network of interdisciplinary palliative care teams that compare their services and outcomes, and learn from a system that provides longitudinal and peer-comparative data and timely information on effective practices and evidence-based interventions

○ Research collaboratories that draw on data generated by the other networks to build new knowledge that improves patient experience, outcomes, effectiveness, and value

Table 1.

Illustrative Contextual Factors That Must Be Considered in Designing a Registry-Based Palliative Care Learning Health System

| Illustrative contextual factors | Potential solutions |

|---|---|

| Palliative care provides services centered on each individual person and family, and their story, not generic care based on “what most people want.” | Measure impact at the level of the individual patient and family, including the degree to which care received is aligned with the changing priorities and concerns of patients and families |

| Palliative care is high-touch, narrative-based care | Preserve narrative while developing simple metrics reflective of the individual patient's priorities |

| Time compression associated with limited prognosis | Use brief patient surveys and minimize data collection burden |

| Illness trajectory changing | Capture and measure against changing priorities for health outcomes and experience |

| Burden, intensity, and complexity of serious illness for patients and caregivers | Focus on limited set of data elements that are needed for decision support, and longitudinal tracking of treatments and associated outcomes |

| Highly heterogeneous set of diseases with varying trajectories, prognoses, symptoms, and treatments | Focus on patient experience, develop core set of metrics for all conditions and create additional disease-specific metrics |

| Frequency of functional and cognitive impairment in serious illness | Use proxies to provide information on behalf of patient when needed |

| Multiple sites of palliative care delivery (home, office, emergency department (ED), inpatient, outpatient, etc.) | Create flexible dashboards that can be adapted to and are interoperable across different settings |

| Broad scope of palliative care delivery with frequent comanagement by a wide variety of teams | Provide for multiple users and inputs to the system |

Go! Begin building a registry-based learning health system for palliative care using rapid cycle tests of change

A wise approach is to start with proof-of-concept, rapid cycle alpha testing in a small number of pilot locations representing a range of contexts. After making needed refinements and improvements, integration of information technology with broad dissemination can follow. Some key factors for launching a palliative care learning health system that has the potential to be successful and sustainable are outlined in Table 2.

Table 2.

Key Factors in Building a Registry-Based Learning Health System for Palliative Care

| Codesign: Ensure multistakeholder engagement in entire process: codesign, coimplement, coevaluate, and co-redesign |

| Feed Forward: Build automated data “feed forward systems” that are continuously available to support daily care decisions, to track changes in health status, and to revise and plan next steps in care |

| Dashboards: Create customized patient and clinician facing dashboards that display graphs of patient-level data (such as depression, distress levels, symptom burden, and caregiver burden) over time, guiding and aligning both the diverse concerns and the inputs necessary to deliver whole-person care in real time; enable tracking of associations between interventions and outcomes of importance to the patient/family; and encourage prompt attention by clinicians to goals and priorities as they change over time, facilitating planning and decision making. |

| Feedback: Use registry data to generate reports for both patients and clinicians, as well as comparative data for population health management, program improvement, research, public reporting, and maintenance of certification. |

| Network Facilitation and Curation: Support growth of curated, patient-facing and clinician-facing networks to promote social and peer support, learning for people living with serious illness, and the work of interdisciplinary teams, respectively. Both networks can provide feedback to improve the functioning of the learning health system registry. |

| Rapid Cycle Testing and Scaling: Start with small iterative pilot tests of learning health system components in different contexts before scaling up |

Challenges in the Upscaling of a Palliative Care Learning Health System

Upscaling a learning health system for palliative care will require intelligent navigation of several domains: cultural change management; careful measurement of performance to demonstrate benefits; establishment of policies that favor culture change and reward measured performance; and alignment of payment systems to promote the above.

Change management

Transformative cultural change is challenging because it involves unlearning and reimagining roles and identity, as well as relationships and power. It requires changes in the attitudes (e.g., I'm on my own in the care of my patients); beliefs (e.g., data reporting is only about billing and coding); and behaviors (e.g., change aversion and change fatigue) that form cultural patterns. Acceptance of a palliative care learning health system will ultimately depend on people seeing, learning, and believing—based on local evidence and firsthand experience—that this approach in fact produces better results that have meaning and value to them and the people they care for.18 Using a codesign approach for planning and implementing the system is likely to facilitate the necessary culture change.

Performance

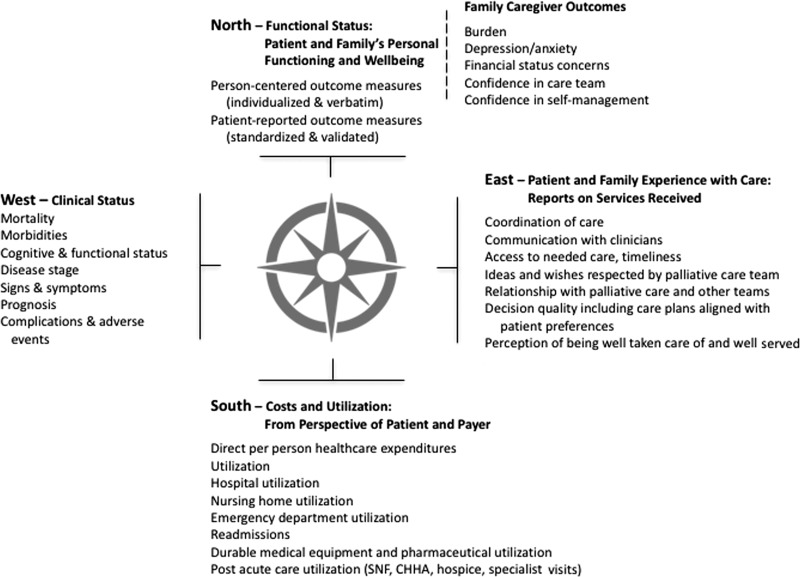

Developing a balanced set of measures is an important part of piloting and scaling a learning health system. The value compass framework may be helpful in developing a “starter-set” of performance measures.33,34 Using the metaphor of a navigational compass, the value compass has four cardinal points of direction: North—Functional Status and Well-being; South—Costs and Utilization; East—Patient and Family Care Experience; and West—Clinical Status. Although all compass points are important, different stakeholders will be more interested in certain points. Maintaining a balanced set of measures supports ongoing coproduction of services that meet multiple needs. Figure 2 illustrates a value compass for palliative care with illustrative measures.

FIG. 2.

A palliative care value compass with illustrative measures that are meaningful to patients, clinicians, researchers, and payers.

Policies

The environmental context favorable to developing and sustaining a learning health system in the palliative care community is, in part, shaped by health policy. Supportive health policies favor active engagement of patients and families in shared decision-making processes that honor their values and preferences, including advance care planning. They favor family-/caregiver-assisted self-management and in-home supports over use of hospitals and nursing homes. They require use of interoperable information technology so that all stakeholders can access the same data in real time. Also, they prioritize quality measures aligned with patient/family priorities. Health policies that reward better health status and quality-of-life results driven by the patient's priorities and preferences and those that reward care systems for making measured improvements on a small, but balanced set of patient-centered performance metrics will support a thriving palliative care learning health system. Health research policies that favor active engagement of patients and families in all aspects of palliative care research will ensure that funding for codesigned trials and studies is available. Recent legislation such as The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act [MACRA] incenting performance on patient-reported outcomes and goals, participation in improvement activities, and prevention of costly emergencies and crises is already starting to support physicians' active participation in state-of-the art collaborative improvement networks that foster both practice-based improvement and transparent public reporting.35

Payment and resource allocation

Supportive financing is critical to the successful implementation and sustainability of learning health systems. It is easy to imagine how well-designed and field-tested models such as value-based bundled payments, shared savings, graded assumption of downside risk, and evolving capitation could accelerate a major shift to support and help finance a national person-centered learning health system for palliative care. Such innovation requires a start-up investment that could come from novel, value-based, patient-focused alternative payment programs as well as the proliferation of broad and effective accountable care organizations.36

In addition to the need for supportive payment and quality measurement structures at the national level, investment of local resources will be needed to integrate learning health system registries into the delivery of palliative care services at the individual organization level. Palliative care program leaders must be prepared to “manage up,” finding ways to show how investment in the human and IT resources necessary to run a high functioning palliative care program that is part of a national learning health system pays dividends for the entire organization.

Conclusion: Onward and Upward

Palliative care provides persons with serious illness and their families goal and value-aligned, whole-person care focused on cocreating the best quality of life possible. Its core values include individualized, patient-centered interdisciplinary and collaborative care that preserves and is guided by the patient. For the palliative care field to achieve its mission of maximizing the quality of life of every person with serious illness, we must be certain that all care is driven by patient and family priorities; however, unless we are capturing those priorities and measuring our interventions and their impact against patient and family goals, we cannot truly know the value of our services. A learning health system offers the opportunity for the field of palliative care to pause and consider—with an expanded group of stakeholders, especially patients and families living with serious illness—what is most important and how to achieve it. To create a successful system, it will be important to learn from previous efforts, and to maintain a balanced approach that is not overweighted toward cost reduction or metrics that may not matter to individual patients and frontline clinicians. The potential for a palliative care learning health system that, by design, brings together enriched information environments to support coproduction of healthcare, facilitated peer networks to support patients and families, collaborative clinician networks to support palliative care program improvement, and collaboratories to support research and the application of research to benefit individual patients is immense. The time to start is now.

Supplementary Material

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Gawande A: Being mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End, 1st ed New York: Metropolitan Books: Henry Holt & Company, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morrison RS, Meier DE: Clinical practice. Palliative care. N Engl J Med 2004;350:2582–2590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine: Measuring What Matters. 2017; http://aahpm.org/quality/measuring-what-matters (last accessed July13, 2017)

- 4.National Palliative Care Registry: National Palliative Care Registry. 2017. https://registry.capc.org (last accessed July13, 2017)

- 5.Global Palliative Care Alliance: QDACT. 2017. www.gpcqa.org/qdact (last accessed July13, 2017)

- 6.Palliative Care Quality Network: PCQN. 2017. www.pcqn.org (last accessed July13, 2017)

- 7.Grossmann C, Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Roundtable on Value & Science-Driven Health Care: Clinical Data as the Basic Staple of Health Learning: Creating and Protecting a Public Good: Workshop Summary. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fuchs VR: Who Shall Live? Health, Economics, and Social Choice. New York: Basic Books, 1975 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Normann R, Ramirez R: From value chain to value constellation: Designing interactive strategy. Harv Bus Rev 1993;71:65–77 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toffler A: The Third Wave, 1st ed New York: Morrow, 1980 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ostrom E: Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alford J: The multiple facets of co-production: Building on the work of Elinor Ostrom. Public Manag Rev 2014;16:299–316 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Batalden M, Batalden P, Margolis P, et al. : Coproduction of healthcare service. BMJ Qual Saf 2016;25:509–517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schneiderman B: Science 2.0. Science 2008;319:1349–1350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nelson EC, Dixon-Woods M, Batalden PB, et al. : Patient focused registries can improve health, care, and science. BMJ 2016;354:i3319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deming WE: Out of the Crisis, 1st MIT Press ed. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindblad S, Ernestam S, Van Citters AD, et al. : Creating a culture of health: Evolving healthcare systems and patient engagement. QJM 2016;110:125–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Margolis PA, Peterson LE, Seid M: Collaborative Chronic Care Networks (C3Ns) to transform chronic illness care. Pediatrics 2013;131 Suppl 4:S219–S223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marshall BC, Nelson EC: Accelerating implementation of biomedical research advances: Critical elements of a successful 10 year Cystic Fibrosis Foundation healthcare delivery improvement initiative. BMJ Qual Saf 2014;23 Suppl 1:i95–i103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stickdorn M, Schneider J: This Is Service Design Thinking: Basics, Tools, Cases. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berwick DM: The science of improvement. JAMA 2008;299:1182–1184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kotter JP: Leading Change. Boston, Mass.: Harvard Business Review Press, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin RC: Agile Software Development: Principles, Patterns, and Practices. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice Hall, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alford J: Engaging Public Sector Clients: From Service-Delivery to Co-Production. Basingstoke England, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eriksson JK, Askling J, Arkema EV: The Swedish Rheumatology Quality Register: Optimisation of rheumatic disease assessments using register-enriched data. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2014;32(5 Suppl 85):S-147–149 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lingfors H, Lindstrom K, Persson LG, et al. : Evaluation of “Live for Life”, a health promotion programme in the County of Skaraborg, Sweden. J Epidemiol Community Health 2001;55:277–282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crandall WV, Margolis PA, Kappelman MD, et al. : Improved outcomes in a quality improvement collaborative for pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Pediatrics 2012;129:e1030–e1041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schechter MS, Fink AK, Homa K, Goss CH: The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry as a tool for use in quality improvement. BMJ Qual Saf 2014;23 Suppl 1:i9–i14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.The National Palliative Care Registry; The Palliative Care Quality Network; The Global Palliative Care Quality Alliance: Quality Measurement Collaboratives and Registries. In: The National Palliative Care Registry; The Palliative Care Quality Network; The Global Palliative Care Quality Alliance, 2016

- 30.Reuben DB, Tinetti ME: Goal-oriented patient care—An alternative health outcomes paradigm. N Engl J Med 2012;366:777–779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ackoff RL: Idealized design—Creative corporate visioning. Omega-Int J Manage S 1993;21:401–410 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hwang J, Christensen CM: Disruptive innovation in health care delivery: A framework for business-model innovation. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27:1329–1335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nelson EC, Batalden PB, Godfrey MM: Quality by Design: A Clinical Microsystems Approach, 1st ed San Francisco: Center for the Evaluative Clinical Sciences at Dartmouth; Jossey-Bass/Wiley, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nelson EC, Mohr JJ, Batalden PB, Plume SK: Improving health care, Part 1: The clinical value compass. Jt Comm J Qual Improv 1996;22:243–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: Delivery System Reform, Medicare Payment Reform. Value Based Programs. 2017. www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs.html

- 36.Song Z: MACRAeconomics: Physician incentives and behavioral economics in the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act. Healthc (Amst) 2016;5:150–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.