Abstract

Carbapenems are considered the last-resort antibiotics to treat infections caused by multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacilli. The Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC) enzyme hydrolyses β-lactam antibiotics including the carbapenems. KPC has been detected worldwide in Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates associated with transposon Tn4401 commonly located in plasmids. Acinetobacter baumannii has become an important multidrug-resistant nosocomial pathogen. KPC-producing A. baumannii has been reported to date only in Puerto Rico. The objective of this study was to determine the whole genomic sequence of a KPC-producing A. baumannii in order to (i) define its allelic diversity, (ii) identify the location and genetic environment of the blaKPC and (iii) detect additional mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance. Next-generation sequencing, Southern blot, PFGE, multilocus sequence typing and bioinformatics analysis were performed. The organism was assigned to the international ST2 clone. The blaKPC-2 was identified on a novel truncated version of Tn4401e (tentatively named Tn4401h), located in the chromosome within an IncA/C plasmid fragment derived from an Enterobacteriaceae, probably owing to insertion sequence IS26. A chromosomally located truncated Tn1 transposon harbouring a blaTEM-1 was found in a novel genetic environment within an antimicrobial resistance cluster. Additional resistance mechanisms included efflux pumps, non-β-lactam antibiotic inactivating enzymes within and outside a resistance island, two class 1 integrons, In439 and the novel In1252, as well as mutations in the topoisomerase and DNA gyrase genes which confer resistance to quinolones. The presence of the blaKPC in an already globally disseminated A. baumannii ST2 presents a serious threat of further dissemination.

Keywords: blaKPC, Tn4401, Acinetobacter baumannii, IS26, IncA/C

Introduction

Acinetobacter baumannii is a Gram-negative, non-fermentative opportunistic pathogen, associated with nosocomial pneumonia, endocarditis, meningitis and bloodstream and urinary tract infections. It has simple growth requirements, is able to survive in dry and moist environments and can tolerate a wide range of pH and temperatures (Getchell-White et al., 1989). This, together with antimicrobial resistance factors, has contributed to its successful adaptation to the hospital environment (Lockhart et al., 2007). Antibiotic resistance in A. baumannii is due to a combination of several factors including low membrane permeability, mutation in its chromosomal genes, overexpression of efflux pumps and acquisition of mobile resistance genes from other organisms (Manchanda et al., 2010).

Carbapenems are commonly considered the β-lactam antibiotics of choice for the treatment of infections caused by multidrug-resistant, Gram-negative bacilli. Carbapenem resistance in A. baumannii is primarily associated with the production of class D carbapenem-hydrolysing β-lactamases (CHDL) and metallo-β-lactamases (MBL). The CHDLs include four major genes clusters, OXA-24/40, OXA-23, OXA-58 and the chromosomally encoded OXA-51. The CHDLs are relatively inefficient compared to other types of carbapenemases, but the presence of insertion sequences (IS) upstream of CHDL genes can provide additional promoters leading to gene overexpression (Turton et al., 2006).

Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC) also renders bacteria resistant to the β-lactam antibiotics, including the carbapenems (Yigit et al., 2001). The KPC gene has been detected worldwide in Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates (Nordmann et al., 2009), in which it is located in transposon Tn4401 (isoforms a to g) in plasmids of different sizes and incompatibility groups (Chmelnitsky et al., 2014). In 2009, our laboratory reported, for the first time, the presence of the KPC gene in A. baumannii, and to our knowledge, KPC-producing A. baumannii has been reported only in Puerto Rico (Robledo et al., 2010; Martinez et al., 2014).

The whole-genome sequence has been a useful tool to understand the evolution of A. baumannii and movement of its resistance genes and virulence factors. A. baumannii is a naturally transformant bacterium which does not discriminate between itself and foreign DNA, hence its great genomic plasticity (Zarrilli et al., 2013). Whole-genome sequence studies have demonstrated that A. baumannii strains have an extensive gene variation between phylogenetically closely related isolates and even from those obtained from the same patient (Wright et al., 2014).

The objective of this study was to determine the whole-genome sequence of a KPC-producing A. baumannii M3AC14-8 in order to (i) define the isolate’s allelic diversity, (ii) identify the location of the KPC gene and its genetic environment and (iii) detect additional mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance.

Methods

Bacterial strains.

In 2014, four multidrug-resistant KPC-producing A. baumannii strains were identified in a single institution from different patients during a 4-month period. They were sent to our laboratory together with their corresponding susceptibility reports and basic epidemiological information. The four isolates were primarily identified in the clinical microbiology laboratory by the VITEK 2 system, and the results were interpreted as recommended by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). The identification of the isolates as A. baumannii was confirmed in our laboratory by biochemical tests (cytochrome c oxidase test and Triple Sugar Iron slants), PCR detection of the blaOXA-51, as described by Woodford et al., (2006), and sequencing of the 16S rDNA gene, as described by Mammeri et al. (2003). PCR screening with family-specific β-lactamase primers for TEM, KPC and OXA carbapenemases was performed as previously described by Moland et al. (2006) and Woodford et al., (2006) using bacterial control strains isolated in our laboratory from previous surveillance studies (Robledo et al., 2010; Martinez et al., 2012). No attempts were made to evaluate patients’ therapies or clinical outcomes.

Determination of genetic relatedness by PFGE.

Genetic relatedness between the A. baumannii isolates was determined by PFGE, as described by Durmaz et al. (2009) and Goering et al. (2010). DNA samples were prepared by in situ lysis of cells encased in agarose and digested with ApaI. PFGE was performed using a CHEF DR III System with the following conditions: switching from 5–30 s for 20 h at 6 V cm−1, 14 °C and 120°angle.

Multilocus sequence typing.

Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) was performed using the Institut Pasteur MLST database available online (http://www.pasteur.fr/mlst).

Next-generation sequencing and bioinformatics analysis.

Whole-genome sequencing was commercially performed by GeneWiz, using an Illumina MiSeq 2×150 bp paired-end configuration. De novo assembly and genome annotation were performed using the Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center Blacklight supercomputer system (Towns et al., 2014) (manuscript in press). ORFs were predicted using Prodigal (version 2.60) (Hyatt et al., 2010). ISs and resistance genes were identified with IS Finder Web site (Siguier, 2006) and RES finder (Zankari et al., 2012), respectively. Prophage sequences within the bacterial genome were identified using PHAST server (Zhou et al., 2011). Whole-genome multiple sequence alignment was performed using Mauve (Darling et al., 2004). The integrons were submitted to INTEGRALL database for integron number assignment (Moura et al., 2009).

Southern blot.

Total DNA plugs were digested with I-CeuI enzyme or S1 nuclease, as described by Liu et al. (1993) and Barton et al. (1995), respectively. Southern blot hybridization was carried out using DIG Easy Hyb Granules using two probes: the 16S rDNA gene to distinguish between chromosomal and plasmid DNA and an internal probe for the KPC gene. Hybridization and development were performed according to the DIG application manual (Roche Applied Science).

Nucleotide accession number.

The 30 scaffolds of the draft genome sequence of A. baumannii M3AC14-8 were submitted to GenBank Genome database and can be found under the accession numbers LDDY00000001 to LDDY00000030.

Results and discussion

Patient data and clinical characteristics

Table 1 shows the clinical characteristics and antimicrobial susceptibilities of the four A. baumannii isolates. The samples were collected from skin and soft tissue, respiratory tract and urine between April and August 2014. The patients’ median age was 54 years (range, 52–90). No differences were observed between gender and hospital ward. The two samples isolated from the general ward were susceptible only to tigecycline, while the two from the intensive care unit were resistant to all tested antibiotics.

Table 1. Clinical information and antimicrobial susceptibility profile of KPC-producing A. baumannii isolates.

GW, general ward; ICU, intensive care unit; AMK, amikacin; AMS, ampicillin-sulbactam; FEP, cefepime; CIP, ciprofloxacin; MEM, meropenem; TGC, tigecycline.

| Strain | Gender | Age (y) | Source | Hospital ward | Collection date | MIC of antibiotic tested (µg ml−1) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMK | AMS | FEP | CIP | MEM | TGC | ||||||

| M3AC14-7 | M | 52 | Respiratory | ICU | 4/11/2014 | ≥64 | ≥32 | ≥64 | ≥4 | ≥16 | ≥8 |

| M3AC14-8 | F | 67 | Skin | ICU | 4/11/2014 | ≥64 | ≥32 | ≥64 | ≥4 | ≥16 | ≥8 |

| M3AC14-16 | M | 90 | Respiratory | GW | 6/3/2014 | ≥64 | ≥32 | ≥64 | ≥4 | ≥16 | 2 |

| M3AC14-32 | F | 63 | Urine | GW | 8/13/2014 | ≥64 | ≥32 | ≥64 | ≥4 | ≥16 | 2 |

Strain typification

The four A. baumannii clinical isolates were positive for OXA-51-like, KPC and TEM genes. Since PFGE-ApaI analysis showed that they had identical pulsotypes (data not shown), only M3AC14-8 strain was selected for further characterization. Using the Institut Pasteur MLST database, the M3AC14-8 strain was assigned to the worldwide- disseminated sequence type ST2. Although A. baumannii ST2 clone has been previously associated with the production of CHDLs (OXA-23, OXA-24/40 and OXA-58) and the VIM MBL, this is the first report of the identification of blaKPC-2 in this international clone (Bakour et al., 2014; Giannouli et al., 2010; Mammina et al., 2011). Multiple genome alignment results using Mauve indicate that the A. baumannii M3AC14-8 genome is closely related to A. baumannii MDR-ZJ06 (accession no. CP001937).

Location and characterization of the genetic environment of the blaKPC

Southern blot hybridization with S1 nuclease and I-CeuI digestion revealed that the KPC gene was chromosomally encoded (data not shown). The chromosomal location of the KPC gene has been previously described from an A. baumannii from Puerto Rico (Martinez et al., 2014), one P. aeruginosa from Colombia (Villegas et al., 2007) and two K. pneumoniae from the USA (Chen et al., 2015; Pecora et al., 2015). In our isolate, KPC-2 gene was identified within a truncated version of the Tn4401e (255 bp deletion upstream of the KPC gene) in which the KPC gene is flanked by the ISKpn6 and ISKpn7 but lacks the transposase and resolvase genes (Figs 1 and 2a). After a literature search, we decided to tentatively name this new isoform Tn4401h. Although Tn4401 has been identified as the genetic element responsible for the dissemination of the KPC gene, non-Tn4401 genetic structures surrounding the KPC gene have been described in P. aeruginosa (Cuzon et al., 2011), Citrobacter freundii, Enterobacter cloacae and a K. pneumoniae isolated from China (Jiang et al., 2010; Shen et al., 2009) and a K. pneumoniae isolated from New Jersey (Chen et al., 2013).

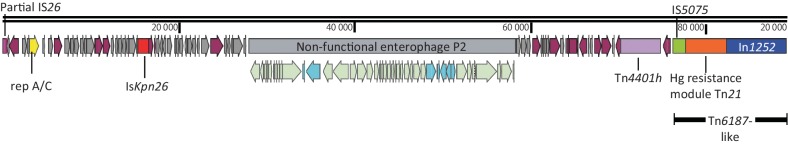

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the 89 kb DNA fragment (scaffold 8) harbouring the KPC-2 gene as part of an IncA/C plasmid inserted in the chromosome of A. baumannii M3AC14-8. This scaffold has 129 ORFs, distributed as 48 hypothetical proteins and 81 proteins with known functions. It begins with a partial copy of the IS26 (nt 1–361) and ends with the novel integron In1252. Other relevant features include an A/C replicase gene, an ISKpn26, a non-functional enterophage P2 and a truncated version of a Tn6187-like transposon. ORFs are portrayed by arrows and coloured according to function as follows: plum arrows, proteins with known function; grey arrows, hypothetical proteins; yellow arrow, A/C replicase; light green arrows, enterophage P2 proteins; turquoise arrows, non-enterophage P2 proteins. Other features represented by coloured rectangles are as follows: pink rectangle, IS26 partial copy; red rectangle, ISKpn26; grey rectangle; non-functional enterophage P2; purple rectangle, Tn4401h; green rectangle, IS5075; orange rectangle, Tn21 mercury resistance module; and blue rectangle, class 1 integron, In1252. Snapgene 2.8.3 was used for map construction.

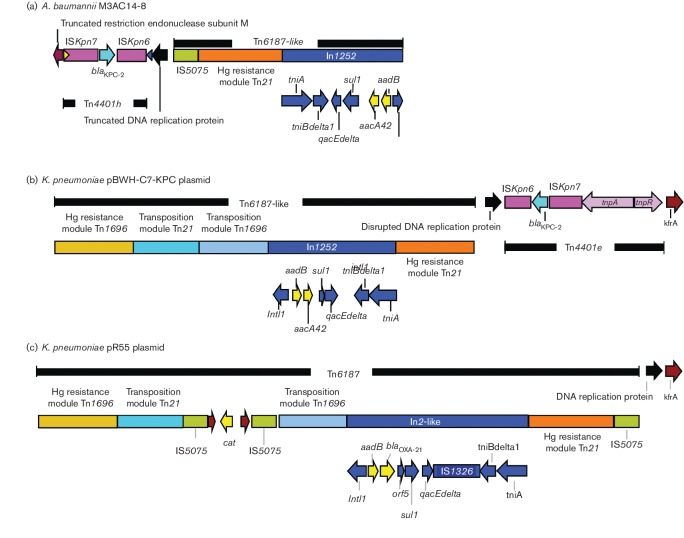

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the genetic background of the KPC-harbouring Tn4401h in A. baumannii M3AC14-8 with the K. pneumoniae KPC-harbouring plasmid pBWH-C7-KPC and the non-KPC pR55 plasmid. (a) The KPC-harbouring Tn4401h in A. baumannii M3AC14-8, which is located at the end of scaffold 8 and consists of a truncated version of the Tn4401e in which the KPC-2 gene is flanked by the ISKpn6 and ISKpn7 but lacks the transposase and resolvase genes. The Tn4401h is flanked between a truncated restriction endonuclease subunit M and a truncated DNA replication protein, followed by a truncated version of a Tn6187-like transposon that contains a copy of an IS5075, a Tn21 mercury resistance module and a novel class 1 integron, In1252. (b) Plasmid pBWH-C7-KPC has a Tn6187-like transposon followed by Tn4401e inserted into the same DNA replication protein but in an inverted orientation when compared to M3AC14-8 strain, followed by the same kfrA protein as plasmid pR55. (c) The plasmid pR55 has a complete and inverted copy of the Tn6187 followed by a DNA replication protein and kfrA protein. Various genes and their directions of transcription are represented by coloured arrows. Turquoise- and light-yellow-coloured arrows represent antimicrobial resistance genes. Yellow and blue triangles represent right inverted repeat of ISKpn7 and Tn4401, respectively. Snapgene 2.8.3 was used for map construction.

Fig. 1 shows the schematic representation of the 89 kb DNA fragment (scaffold 8) harbouring the Tn4401h. This scaffold has a 54 % GC content and 129 ORFs, distributed as 48 hypothetical proteins and 81 proteins with known functions. Among the identified proteins are a partial copy of IS26 at the beginning of the scaffold (nt 1–361), an A/C replicase gene, an ISKpn26, a non-functional enterophage P2 and a truncated version of a Tn6187-like transposon. The scaffold ends with a class 1 integron. Additional copies of IS26 were found in other scaffolds of the draft genome sequence (three complete and eight incomplete copies at the end of the scaffolds), which made it impossible to assemble the complete genome sequence. Recent studies have demonstrated that IS26 has an important role in the creation, dissemination and reorganization of antimicrobial resistance gene clusters in Entobacteriaceae plasmids, including IncA/C plasmids, and in A. baumannii isolates (He et al., 2015; Nigro et al., 2013; Lean et al., 2015). IncA/C plasmids are large conjugative plasmid from Enterobacteriaceae with a broad host range and different hotspot sites for the integration of multidrug resistance (MDR) genes (Fricke et al., 2009). The IncA/C plasmid has been previously reported in A. baumannii only by Zhang et al. (2014) in a survey of Gram-negative bacilli clinical isolates from China; however it is unknown if the plasmid was integrated into the chromosome since they used total DNA extraction to detect the replicase genes by PCR.

The IncA/C plasmid fragment in M3AC14-8 strain is closely related to the KPC-harbouring plasmid pBWH-C7-KPC from a K. pneumoniae isolated in Massachusetts, USA (BioSample accession no. SAMN03657219; Pecora et al., 2015) and the non-KPC-producing pR55 plasmid from a K. pneumoniae isolated in 1969 in France (accession no. JQ010984; Doublet et al., 2012). Similar to plasmid pBWH-C7-KPC, M3AC14-8 strain contained 37 of the 42 proteins encoded by the enterophage P2 (accession no. AF063097) inserted at the same position into a hypothetical protein; however, plasmid pR55 does not contain the P2 phage (plasmid comparison not shown).

Fig. 2 shows a schematic representation of the genetic background surrounding the Tn4401 in the KPC-producing M3AC14-8 strain (Fig. 2a) and its comparison with the KPC-harbouring plasmid pBWH-C7-KPC (Fig. 2b) and the non-KPC-plasmid pR55 (Fig. 2c), obtained from K. pneumoniae isolates. The KPC-producing A. baumannii M3AC14-8 contained a 19.3 kb DNA fragment, which includes a truncated restriction endonuclease subunit M and a truncated DNA replication protein flanking the Tn4401h, followed by a truncated version of a Tn6187-like transposon (Fig. 2a). Tn4401h retained the transposon right inverted repeat (RIR) sequence (blue triangle in Fig. 2a) and 14/15 nucleotides of the ISKpn7 RIR (5′-TGTTAGCAGCAGTGT-3′, mismatched nucleotide is underlined, yellow rectangle in Fig. 2a), as described by Naas et al. (2008). Upstream of the RIR of the Tn4401 in M3AC14-8 strain, a 5 bp DNA sequence (GGGAA) and the 5′ end fragment of a DNA replication protein (accession no. WP_014342221) were identified to be similar to plasmid pBWH-C7-KPC.

The truncated version of Tn6187-like transposon in M3AC14-8 strain contains a copy of an IS5075, a Tn21 mercury resistance module and a novel class 1 integron with the following gene cassette array (5′CS-aadB, aacA42-3′CS) (Fig. 2a). INTEGRALL database assigned the name In1252 to this novel integron. The transposition modules from Tn21 and Tn1696, as well as the mercury resistance module from Tn1696, are missing in M3AC14-8 strain when compared with plasmid pR55, which has a complete and inverted copy of the Tn6187 (Fig. 2c). We speculate that the IS26 element located in the IncA/C fragment (Fig. 1) could have caused the inversion of the truncated version of Tn6187 and the novel Tn4401h by an intramolecular transposition cis event (He et al., 2015) before the plasmid was integrated into the A. baumannii chromosome. The aacA42 gene cassette in the novel integron In1252 has only been described twice in the literature associated with blaGES type enzymes and blaOXA-2 in two integrons, In647 (accession no. GQ337064) and In724 (accession no. JN596280) identified in clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa from Spain (Viedma et al., 2009) and Enterobacteriaceae from Mexico (Barrios et al., 2012), respectively.

As previously mentioned, similar to M3AC14-8 strain, K. pneumoniae plasmid pBWH-C7-KPC has a Tn6187-like transposon followed by Tn4401e but in an inverted orientation (Fig. 2b), inserted into the same DNA replication protein, and this insertion generates the same 5 bp duplication site (GGGAA) observed in M3AC14-8 strain (Fig. 2a). Plasmid pBWH-C7-KPC, in addition, has the same gene cassette array (5′CS-aadB, aacA42-3′CS) in the class 1 integron as M3AC14-8 strain; however, plasmid pBWH-C7-KPC does not have an IS5075 copy upstream to the Tn21 mercury resistance module. DNA sequence analysis of K. pneumoniae pBWH-C7-KPC plasmid demonstrated a 128 bp localized in nt 59530–59657 identical to the 128 bp of ISKpn7 (including the 15 bp of the RIR) localized in nt 172436–172563. Since the DNA fragment between them (which is mostly the tra genes responsible for plasmid conjugation) present in pBWH-C7-KPC plasmid, but not found in M3AC14-8 strain, we speculate that Tn4401h may have resulted from a homologous recombination event between the 128 bp regions after the inversion event of Tn4401 and the truncated version of Tn6187-like transposon. The locations of these features may suggest that these two KPC-carrying IncA/C plasmids have evolved from a common ancestor through multiple genetic events.

blaTEM-1 and its genetic environment

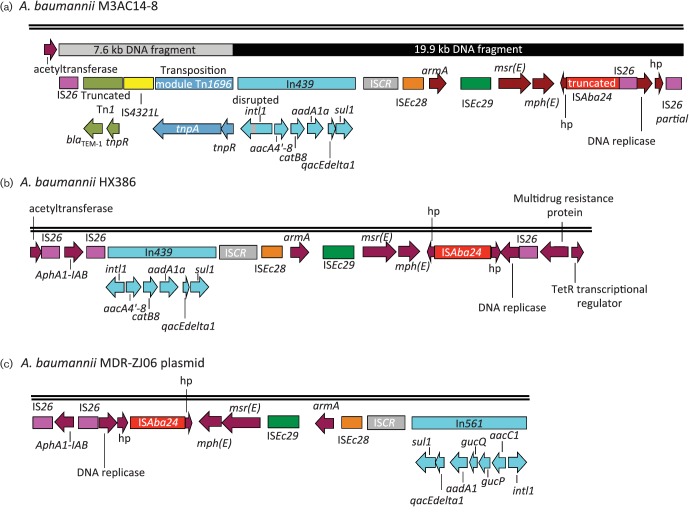

Fig. 3 shows a schematic representation of the immediate environment surrounding the blaTEM-1 in M3AC14-8 strain (Fig. 3a) located upstream of an antimicrobial resistance cluster and its comparison with the genetic structure of A. baumannii HX386 (accession no. CP010779) (Fig. 3b) and from A. baumannii MDR-ZJ06 plasmid (accession no. CP001938) (Fig. 3c). As shown in Fig. 3(a), the chromosomally located blaTEM-1 in M3AC14-8 strain (scaffold 2) was identified in a novel 7.6 kb genetic environment, followed by a 19.9 kb DNA fragment that contains the antimicrobial resistance cluster. The order of the genes in this novel 7.6 kb DNA fragment consists of an IS26, a truncated version of a Tn1 harbouring blaTEM-1 and tnpR, an IS4321L, followed by the tnpA and tnpR genes of a truncated version of Tn1696 transposon (Fig. 3a). The 7.6 kb DNA fragment was inserted upstream of a 19.9 kb antimicrobial resistance cluster that is similar to that found in A. baumannii HX386, sharing 98 % of its DNA sequence (Fig. 3b), and in A. baumannii MDR-ZJ06 plasmid, sharing 91 % of its DNA sequence (Fig. 3c). The M3AC14-8 cluster includes In439 class I integron, five different IS elements (two IS26 copies, one copy of a truncated ISAba24 and one copy each of ISCR, ISEc28 and ISEc29) and the antimicrobial resistance genes for macrolides (msr[E] and mph[E])and the 16S rDNA methyltransferase (armA) that confers resistance to aminoglycosides (Fig. 3a). The gene cassette of the In439 class 1 integron (5′CS-aacA4′-8-catB8-aadA1a-3′CS) in M3AC14-8 strain is highly similar to A. baumannii HX386, except that, in M3AC14-8 strain, the intI1 gene is disrupted by 415 bp which includes a duplication of 219 bp of the intI1 gene and 196 bp that belongs to an IS26 fragment. The In439 confers resistance to aminoglycosides (aacA4′-8 and aadA1a) and to chloramphenicol (catB8). A. baumannii MDR-ZJ06 plasmid contains a different class 1 integron, In561 (5′CS-aacC1-gcuP-gcuQ-aadA1a-3′CS), as shown in Fig. 3(c). A. baumannii HX386 and A. baumannii MDR-ZJ06 plasmid share 93 % of their DNA sequence; the only difference is that the class 1 integron is In439 in HX386 strain and In561 in MDR-ZJ06 plasmid and the presence of a third IS26 copy in A. baumannii HX386 (Fig. 3b, c). Genomic analysis suggests that, in A. baumannii HX386, the chromosomal integration of the A. baumannii MDR-ZJ06 plasmid was mediated by IS26, and this integration generated the third copy of IS26 and an 8 bp duplication (AGGATGAG), flanking the first and third copies of IS26 (Fig. 3b). Data analysis suggests that, in M3AC14-8 strain, the IS26 also had a role in the plasmid integration and remodelling of the DNA, since the same 8 bp duplication (AGGATGAG) was found at the left side of the IS26 upstream of blaTEM-1. An intramolecular transposition in trans of IS26 was responsible for the DNA inversion and the truncated version of the ISAba24 in M3AC14-8 strain when compared with A. baumannii HX386. IS26 may also been involved in the integration of the 7.6 kb DNA fragment that contains the truncated Tn1 harbouring the blaTEM-1 upstream of the 19.9 kb DNA fragment.

Fig. 3.

A schematic representation of the genetic background of TEM-1-harbouring Tn1 in A. baumannii M3AC14-8 located upstream of an antimicrobial resistance cluster and its comparison with the genetic structure of the A. baumannii HX386 and the A. baumannii MDR-ZJ06 plasmid. (a) The TEM-1 β-lactamase gene was identified in a novel 7.6 kb genetic environment that consists of IS26, a truncated version of a Tn1, an IS4321L, followed by a truncated Tn1696. This 7.6 kb DNA fragment was inserted upstream of a 19.9 kb antimicrobial resistance cluster that is similar to that found in A. baumannii HX386 (b) and in a plasmid from A. baumannii MDR-ZJ06 (c). A. baumannii MDR-ZJ06 plasmid contains a different class 1 integron, In561 (c). Genes and their directions of transcription are represented by coloured arrows. Hypothetical proteins are indicated by hp. Snapgene 2.8.3 was used for map construction.

Other resistance mechanisms

Additional mechanisms of antibiotic resistance to non-β-lactam antibiotics could be inferred from the antimicrobial susceptibility results and bioinformatics analysis. The presence of an ISAba1 element adjacent to the ampC cephalosporinase (blaADC-25) gene was identified, which might result in an overexpression of the gene (Héritier et al., 2006). The OXA-51 carbapenemase variant present in M3AC14-8 strain was blaOXA-66, but no IS element was found located upstream of the gene. A partially sequenced resistance island (scaffolds 18 and 23), similar to AbaR22 from A. baumannii MDR-ZJ06, was found interrupting the comM gene in M3AC14-8 strain. The resistance island includes resistance genes for streptomycin (strA and strB) and the gene that codes for the tet(B) efflux pump which confers resistance to tetracyclines. The following additional efflux pump systems were identified outside the resistance island: AdeABC, AdeIJK, AbeM and AbeS. Amino acid variations associated with overexpression of the AdeABC efflux pump in the two-component regulatory system adeSR were identified, adeS and adeR. The amino acid variation N268H was identified in adeS (Hornsey et al., 2011); and the V120I, L136I variation, in adeR (Ardebili et al., 2014). Mutations encoding amino acid substitutions associated with quinolone resistance were identified in DNA gyrase (gyrA) and topoisomerase (parC), the S83L and S80L substitutions, respectively (Sun et al., 2015).

Plasmid characterization

Two complete and circularized plasmids were found in M3AC14-8 strain. Both plasmids, p1M3AC14-8 and p2M3AC14-8, exhibited a replicase gene and two mobilization genes but lacked the genes involved in partition and conjugation. The plasmid p1M3AC14-8 is 5541 bp with a G+C content of 35 % and is very similar to a 5644 bp A. baumannii AYE plasmid, p1ABAYE (accession no. CU459137), sharing 91 % of their DNA sequence (with a 98 % of identity with an expected value of 0). As expected, the replicase gene, repA (316 aa), identified in plasmid p1M3AC14-8, is identical to the replicase gene of p1ABAYE and belongs to the homology group 11 (Gr11) identified by A. baumannii PCR-based replicon typing scheme described by Bertini et al. (2010). The plasmid consists of six ORFs, two hypothetical proteins, a mobilization protein MobL, a putative mobilization protein MobS and a putative toxin–antitoxin system.

The second plasmid, p2M3AC14-8, was determined to be 18 043 bp with an average G+C percentage of 35. Blast against NCBI database shows that p2M3AC14-8 is a novel plasmid sharing only 38 % of the DNA sequence (with 99 % identity and an expected value of 0) with a 10 679 bp A. baumannii plasmid pMMA2 (accession no. GQ377752). Prodigal identified 20 OFRs, nine hypothetical proteins, two conjugal transfer proteins, traA and trbL, an outer membrane protein, a cro-like protein, a putative toxin–antitoxin system, a septicolysin, an addiction module toxin RelE, a Cro/Cl family transcriptional regulator and insertion sequence ISAba11. The replicase gene (189 aaa) is identical to GenBank accession number WP_001096622; however, it was not detected by the available A. baumannii or Enterobacteriaceae PCR-based replicon typing scheme, as described by Bertini et al. (2010) and Carattoli et al. (2005), respectively.

In summary, this is the first report of the identification of blaKPC-2 in an international A. baumannii ST2 clone with Tn4401h, a novel truncated version of the Tn4401e, identified as the genetic element surrounding the KPC gene. The KPC gene was chromosomally encoded within a broad-spectrum IncA/C putative plasmid probably acquired from an Enterobacteriaceae. We hypothesize that the KPC carrying IncA/C plasmid cannot replicate in A. baumannii and, therefore, was inserted into the chromosome. Multiple copies of IS26 were found in the genome of KPC-producing A. baumannii, suggesting high activity of this IS. We hypothesize that IS26 was responsible for the chromosomal insertion of the blaKPC-2 harbouring Tn4401h, as well as the Tn1 harbouring the blaTEM-1. Similar to M3AC14-8 strain, the chromosomal location of the KPC gene was previously identified in another clinical isolate of A. baumannii M3AC9-7 strain from Puerto Rico (Martínez et al., 2015). However, M3AC9-7 strain belongs to a novel clone, ST250, and the ISEcp1 was responsible for the transposition of the 26.5 kb fragment that contains the blaKPC-3 harbouring Tn4401b and a fragment of a narrow host range IncFII plasmid from an unknown Enterobacteriaceae (Martinez et al., 2014). Two class 1 integrons were identified in the M3AC14-8 strain chromosome, In439 (aacA4′-8-cat8-aadA1) and the novel In1252 (aadB-aacA42). Additional resistance mechanisms identified by bioinformatics included efflux pump systems and non-β-lactam antibiotic inactivating enzymes within and outside a resistance island. These genetic elements may play a significant role in the antimicrobial resistance pattern of the strain. The worldwide dissemination of KPC-producing A. baumannii ST2 clone might be expected and should be monitored.

Acknowledgements

This work used the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE), which is supported by the National Science Foundation grant number OCI-1053575. Specifically, it used the Blacklight supercomputer system at the Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center (PSC). Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. This work was also supported by the PSC’s National Institutes of Health Minority Access to Research Careers grant T36-GM-095335 and the University of Puerto Rico Medical Sciences Campus grants MBRS/RISE (R25GM061838-14), RCMI/NIH (8G12-MD007600), Proyecto Adopte un Gen and Associate Deanship for Biomedical Sciences Graduate Program School of Medicine, Medical Sciences Campus, University of Puerto Rico. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation or the decision to submit the work for publication. We thank Drs Lynn Bry and Nicole Pecora, at the Harvard Medical School, for providing the K. pneumoniae pBWH-C7-KPC plasmid assembled contig, and Thomas Jove, INTEGRALL curator, for the detail analysis of the integron. We also thank Dr Wieslaw J. Kozek for reviewing the manuscript.

This research project constitutes a partial fulfilment of the doctoral thesis dissertation of T. M.

Abbreviations:

- CHDL

carbapenem-hydrolysing β-lactamase

- CLSI

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute

- IS

insertion sequence

- KPC

Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase

- MBL

metallo-β-lactamase

- MLST

multilocus sequence typing

- MDR

multidrug resistance

- RIR

right inverted repeat

References

- Ardebili A., Lari A. R., Talebi M.(2014). Correlation of ciprofloxacin resistance with the AdeABC efflux system in Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates. Ann Lab Med 34433–438. 10.3343/alm.2014.34.6.433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakour S., Alsharapy S. A., Touati A., Rolain J. M.(2014). Characterization of Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates carrying bla(OXA-23) carbapenemase and 16S rRNA methylase armA genes in Yemen. Microb Drug Resist 20604–609. 10.1089/mdr.2014.0018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrios H., Garza-Ramos U., Ochoa-Sanchez L. E., Reyna-Flores F., Rojas-Moreno T., Morfin-Otero R., Rodriguez-Noriega E., Garza-Gonzalez E., Gonzalez G., et al. (2012). A plasmid-encoded class 1 integron contains GES-type extended-spectrum β-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae clinical isolates in Mexico. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 564032–4034. 10.1128/AAC.05980-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton B. M., Harding G. P., Zuccarelli A. J.(1995). A general method for detecting and sizing large plasmids. Anal Biochem 226235–240. 10.1006/abio.1995.1220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertini A., Poirel L., Mugnier P. D., Villa L., Nordmann P., Carattoli A.(2010). Characterization and PCR-based replicon typing of resistance plasmids in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 544168–4177. 10.1128/AAC.00542-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carattoli A., Bertini A., Villa L., Falbo V., Hopkins K. L., Threlfall E. J.(2005). Identification of plasmids by PCR-based replicon typing. J Microbiol Methods 63219–228. 10.1016/j.mimet.2005.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Chavda K. D., Fraimow H. S., Mediavilla J. R., Melano R. G., Jacobs M. R., Bonomo R. A., Kreiswirth B. N.(2013). Complete nucleotide sequences of blaKPC-4-and blaKPC-5-harboring IncN and IncX plasmids from Klebsiella pneumoniae strains isolated in New Jersey. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57269–276. 10.1128/AAC.01648-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Chavda K. D., DeLeo F. R., Bryant K. A., Jacobs M. R., Bonomo R. A., Kreiswirth B. N.(2015). Genome sequence of a Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence type 258 isolate with prophage-encoded K. pneumoniae carbapenemase. Genome Announc 3e00659-15. 10.1128/genomeA.00659-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chmelnitsky I., Shklyar M., Leavitt A., Sadovsky E., Navon-Venezia S., Ben Dalak M., Edgar R., Carmeli Y.(2014). Mix and match of KPC-2 encoding plasmids in Enterobacteriaceae-comparative genomics. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 79255–260. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2014.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuzon G., Naas T., Villegas M. V., Correa A., Quinn J. P., Nordmann P.(2011). Wide dissemination of Pseudomonas aeruginosa producing beta-lactamase blaKPC-2 gene in Colombia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 555350–5353. 10.1128/AAC.00297-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling A. C., Mau B., Blattner F. R., Perna N. T.(2004). Mauve: multiple alignment of conserved genomic sequence with rearrangements. Genome Res 141394–1403. 10.1101/gr.2289704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doublet B., Boyd D., Douard G., Praud K., Cloeckaert A., Mulvey M. R.(2012). Complete nucleotide sequence of the multidrug resistance IncA/C plasmid pR55 from Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated in 1969. J Antimicrob Chemother 672354–2360. 10.1093/jac/dks251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durmaz R., Otlu B., Koksal F., Hosoglu S., Ozturk R., Ersoy Y., Aktas E., Gursoy N. C., Caliskan A.(2009). The optimization of a rapid pulsed-field gel electrophoresis protocol for the typing of Acinetobacter baumannii, Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp. Jpn J Infect Dis 62 372–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricke W. F., Welch T. J., McDermott P. F., Mammel M. K., LeClerc J. E., White D. G., Cebula T. A., Ravel J.(2009). Comparative genomics of the IncA/C multidrug resistance plasmid family. J Bacteriol 1914750–4757. 10.1128/JB.00189-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getchell-White S. I., Donowitz L. G., Gröschel D. H.(1989). The inanimate environment of an intensive care unit as a potential source of nosocomial bacteria: evidence for long survival of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 10402–407. 10.2307/30144208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannouli M., Cuccurullo S., Crivaro V., Di Popolo A., Bernardo M., Tomasone F., Amato G., Brisse S., Triassi M., et al. (2010). Molecular epidemiology of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in a tertiary care hospital in Naples, Italy, shows the emergence of a novel epidemic clone. J Clin Microbiol 481223–1230. 10.1128/JCM.02263-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goering R. V.(2010). Pulsed field gel electrophoresis: a review of application and interpretation in the molecular epidemiology of infectious disease. Infect Genet Evol 10866–875. 10.1016/j.meegid.2010.07.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S., Hickman A. B., Varani A. M., Siguier P., Chandler M., Dekker J. P., Dyda F.(2015). Insertion sequence IS 26 reorganizes plasmids in clinically isolated multidrug-resistant bacteria by replicative transposition. MBio 61–14. 10.1128/mBio.00762-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Héritier C., Poirel L., Nordmann P.(2006). Cephalosporinase over-expression resulting from insertion of ISAba1 in Acinetobacter baumannii. Clin Microbiol Infect 12123–130. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2005.01320.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornsey M., Loman N., Wareham D. W., Ellington M. J., Pallen M. J., Turton J. F., Underwood A., Gaulton T., Thomas C. P., et al. (2011). Whole-genome comparison of two Acinetobacter baumannii isolates from a single patient, where resistance developed during tigecycline therapy. J Antimicrob Chemother 661499–1503. 10.1093/jac/dkr168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyatt D., Chen G. L., Locascio P. F., Land M. L., Larimer F. W., Hauser L. J.(2010). Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics 11119. 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Yu D., Wei Z., Shen P., Zhou Z., Yu Y.(2010). Complete nucleotide sequence of Klebsiella pneumoniae multidrug resistance plasmid pKP048, carrying blaKPC-2, blaDHA-1, qnrB4, and armA. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 543967–3969. 10.1128/AAC.00137-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lean S. S., Yeo C. C., Suhaili Z., Thong K. L.(2015). Whole-genome analysis of an extensively drug-resistant clinical isolate of Acinetobacter baumannii AC12: insights into the mechanisms of resistance of an ST195 clone from Malaysia. Int J Antimicrob Agents 45178–182. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S. L., Hessel A., Sanderson K. E.(1993). Genomic mapping with I-Ceu I, an intron-encoded endonuclease specific for genes for ribosomal RNA, in Salmonella spp., Escherichia coli, and other bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 906874–6878. 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockhart S. R., Abramson M. A., Beekmann S. E., Gallagher G., Riedel S., Diekema D. J., Quinn J. P., Doern G. V.(2007). Antimicrobial resistance among gram-negative bacilli causing infections in intensive care unit patients in the United States between 1993 and 2004. J Clin Microbiol 453352–3359. 10.1128/JCM.01284-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mammeri H., Poirel L., Mangeney N., Nordmann P., Central L., Chenevier A.(2003). Chromosomal integration of a cephalosporinase gene from Acinetobacter baumannii into Oligella urethralis as a source of acquired resistance to beta-lactams. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 471536–1542. 10.1128/AAC.47.5.1536-1542.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mammina C., Bonura C., Aleo A., Calà C., Caputo G., Cataldo M. C., Benedetto A. D., Distefano S., Fasciana T., et al. (2011). Characterization of Acinetobacter baumannii from intensive care units and home care patients in Palermo, Italy. Clin Microbiol Infect 17E12–E15. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03654.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manchanda V., Sanchaita S., Singh N.(2010). Multidrug resistant acinetobacter. J Glob Infect Dis 2291. 10.4103/0974-777X.68538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez T., Vazquez G. J., Aquino E. E., Goering R. V., Robledo I. E.(2012). Two novel class I integron arrays containing IMP-18 metallo-β-lactamase gene in Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates from Puerto Rico. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 562119–2121. 10.1128/AAC.05758-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez T., Vázquez G. J., Aquino E. E., Martínez I., Robledo I. E.(2014). ISEcp1-mediated transposition of blaKPC into the chromosome of a clinical isolate of Acinetobacter baumannii from Puerto Rico. J Med Microbiol 631644–1648. 10.1099/jmm.0.080721-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez T., Ropelewski A. J., González-Mendez R., Vázquez G. J., Robledo I. E.(2015). Draft genome sequence of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing Acinetobacter baumannii strain M3AC9-7, isolated from Puerto Rico. Genome Announc 3e00274-15. 10.1128/genomeA.00274-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moland E. S., Hanson N. D., Black J. A., Hossain A., Song W., Thomson K. S.(2006). Prevalence of newer beta-lactamases in gram-negative clinical isolates collected in the United States from 2001 to 2002. J Clin Microbiol 443318–3324. 10.1128/JCM.00756-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moura A., Soares M., Pereira C., Leitão N., Henriques I., Correia A.(2009). INTEGRALL: a database and search engine for integrons, integrases and gene cassettes. Bioinformatics 251096–1098. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naas T., Cuzon G., Villegas M. V., Lartigue M. F., Quinn J. P., Nordmann P.(2008). Genetic structures at the origin of acquisition of the beta-lactamase bla KPC gene. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 521257–1263. 10.1128/AAC.01451-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigro S. J., Farrugia D. N., Paulsen I. T., Hall R. M.(2013). A novel family of genomic resistance islands, AbGRI2, contributing to aminoglycoside resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii isolates belonging to global clone 2. J Antimicrob Chemother 68554–557. 10.1093/jac/dks459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordmann P., Cuzon G., Naas T.(2009). The real threat of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing bacteria. Lancet Infect Dis 9 228–236. 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70054-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecora N. D., Li N., Allard M., Li C., Albano E., Delaney M., Dubois A., Onderdonk A. B., Bry L.(2015). Genomically informed surveillance for carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in a health care system. MBio 6e01030–01015. 10.1128/mBio.01030-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robledo I. E., Aquino E. E., Santé M. I., Santana J. L., Otero D. M., León C. F., Vázquez G. J.(2010). Detection of KPC in Acinetobacter spp. in Puerto Rico. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 541354–1357. 10.1128/AAC.00899-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen P., Wei Z., Jiang Y., Du X., Ji S., Yu Y., Li L., Yu N.(2009). Novel genetic environment of the carbapenem-hydrolyzing beta-lactamase KPC-2 among Enterobacteriaceae in China. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 534333–4338. 10.1128/AAC.00260-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siguier P., Perochon J., Lestrade L., Mahillon J., Chandler M.(2006). ISfinder: the reference centre for bacterial insertion sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 34D32–D36. 10.1093/nar/gkj014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C., Hao J., Dou M., Gong Y.(2015). Mutant prevention concentrations of levofloxacin, pazufloxacin and ciprofloxacin for A. baumannii and mutations in gyrA and parC genes. J Antibiot 68313–317. 10.1038/ja.2014.150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towns J., Cockerill T., Dahan M., Foster I., Gaither K., Grimshaw A., Hazlewood V., Lathrop S., Lifka D., et al. (2014). XSEDE: accelerating scientific discovery. Comput Sci Eng 1662–74. 10.1109/MCSE.2014.80 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turton J. F., Ward M. E., Woodford N., Kaufmann M. E., Pike R., Livermore D. M., Pitt T. L.(2006). The role of ISAba1 in expression of OXA carbapenemase genes in Acinetobacter baumannii. FEMS Microbiol Lett 25872–77. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00195.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viedma E., Juan C., Acosta J., Zamorano L., Otero J. R., Sanz F., Chaves F., Oliver A.(2009). Nosocomial spread of colistin-only-sensitive sequence type 235 Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates producing the extended-spectrum beta-lactamases GES-1 and GES-5 in Spain. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 534930–4933. 10.1128/AAC.00900-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villegas M. V., Lolans K., Correa A., Kattan J. N., Lopez J. A., Quinn J. P., Colombian Nosocomial Resistance Study Group (2007). First identification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates producing a KPC-type carbapenem-hydrolyzing beta-lactamase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 511553–1555. 10.1128/AAC.01405-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolter D. J., Khalaf N., Robledo I. E., Vázquez G. J., Santé M. I., Aquino E. E., Goering R. V., Hanson N. D.(2009). Surveillance of carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from Puerto Rican medical center hospitals: dissemination of KPC and IMP-18 beta-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 531660–1664. 10.1128/AAC.01172-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodford N., Ellington M. J., Coelho J. M., Turton J. F., Ward M. E., Brown S., Amyes S. G., Livermore D. M.(2006). Multiplex PCR for genes encoding prevalent OXA carbapenemases in Acinetobacter spp. Int J Antimicrob Agents 27351–353. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright M. S., Haft D. H., Harkins D. M., Perez F., Hujer K. M., Bajaksouzian S., Benard M. F., Jacobs M. R., Bonomo R. A., Adams M. D.(2014). New insights into dissemination and variation of the health care-associated pathogen Acinetobacter baumannii from genomic analysis. MBio 5e00963–13. 10.1128/mBio.00963-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yigit H., Queenan A. M., Anderson G. J., Domenech-Sanchez A., Biddle J. W., Steward C. D., Alberti S., Bush K., Tenover F. C.(2001). Novel carbapenem-hydrolyzing beta-lactamase, KPC-1, from a carbapenem-resistant strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 451151–1161. 10.1128/AAC.45.4.1151-1161.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zankari E., Hasman H., Cosentino S., Vestergaard M., Rasmussen S., Lund O., Aarestrup F. M., Larsen M. V.(2012). Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J Antimicrob Chemother 672640–2644. 10.1093/jac/dks261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarrilli R., Pournaras S., Giannouli M., Tsakris A.(2013). Global evolution of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii clonal lineages. Int J Antimicrob Agents 4111–19. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G. Q., Yao Y. H., Yu X. L., Niu J. J.(2014). A survey of five broad-host-range plasmids in gram-negative bacilli isolated from patients. Plasmid 749–14. 10.1016/j.plasmid.2014.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y., Liang Y., Lynch K. H., Dennis J. J., Wishart D. S.(2011). PHAST: a fast phage search tool. Nucleic Acids Res 39W347–W352. 10.1093/nar/gkr485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]