Abstract

Objective

Treatment selection for recurrent ovarian cancer is typically based on the duration of time between the completion of adjuvant, platinum-based therapy and the time of recurrence, the platinum free interval (PFI). We examined the use of, and outcomes associated with platinum-based chemotherapy based on the PFI in women with recurrent ovarian cancer.

Methods

The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-Medicare database was used to identify women aged >65 years with epithelial ovarian cancer who underwent surgery and platinum-based chemotherapy and who developed a recurrence >3 months after the completion of adjuvant therapy. Patients were stratified by PFI into 3 groups: PFI <6 months, PFI 7-12 months, and PFI >12 months. Multivariable models were used to examine predictors of use of platinum-based therapy and survival for each group.

Results

A total of 2,369 patients were identified. In women with a PFI of ≤6 months, treatment consisted of platinum-based combination therapy in 28.2%, single agent platinum in 5.2% and non-platinum therapy in 66.6%. Corresponding rates of these treatments among women with a PFI of 7–12 months were 39.7%, 12.4% and 47.9%, respectively; the rates were 57.6%, 13.2% and 29.3% in those with a PFI of >12 months, respectively. Median survival was 13, 18, and 27 months for patients with a PFI of ≤6 months, 7–12 months, and >12 months, respectively (P<0.0001). For all three groups, platinum combination therapy was associated with decreased risk of death compared to non-platinum based therapy.

Conclusion

Platinum free interval is a strong predictor of survival in elderly women with recurrent ovarian cancer. There is widespread variation in treatment selection for women with recurrent ovarian cancer with many women receiving non-guideline based regimens.

Introduction

Despite a high initial response rate to surgery and chemotherapy, women with ovarian cancer are at significant risk for recurrence following primary treatment. Among patients with early-stage ovarian cancer, 25% will have a recurrence, and 80% of patients with advanced disease will recur.1 A wide variety of cytotoxic and biologic agents are now available for the treatment of women with recurrent ovarian cancer.2–4

Treatment selection for recurrent ovarian cancer is typically based on the duration of time between the completion of adjuvant platinum-based therapy and the time of recurrence, the so-called platinum free interval (PFI).5,6 Those women who have a short PFI are less likely to respond to retreatment with platinum-based therapy, while patients with a longer PFI are more likely to respond.7 The PFI is also an important prognostic factor; a longer PFI is associated with improved survival.8

Women with recurrent ovarian cancer and a PFI of ≤6 months are typically classified as platinum resistant and recommendations are for treatment with non-platinum based chemotherapy. Those women with a PFI of >6 months are considered to have platinum sensitive disease and treatment recommendations generally encourage retreatment with platinum-based therapy, usually platinum-based combination therapy. Patients with a long PFI (>12 months) have the highest response rate to platinum retreatment and thus the strongest rationale for receiving such therapy5,9

Despite the availability of treatment recommendations for women with recurrent ovarian cancer based on PFI, little is known about the actual patterns of care for women with ovarian cancer in the general population. We performed a population-based analysis in elderly women with recurrent ovarian cancer to determine the use and outcomes of platinum-based chemotherapy based on clinical characteristics and the length of the platinum free interval.

Methods

Data Source

We used the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare database for the analysis.10–16 The SEER program is a population-based tumor registry maintained by the National Cancer Institute that currently covers approximately 28% of the US population.17 SEER captures data on date of cancer diagnosis, tumor histology, location, stage, treatment, and survival, as well as demographic and selected census tract-level information. Using a matching algorithm, 93–94% of SEER patients diagnosed at age 65 or older are linked to Medicare health care claims.18,19 The Medicare claims database captures information on patients with Medicare part A (inpatient) and part B (outpatient), including billed claims, services, and diagnoses. These two files are linked and provide data on initial services and all follow-up care longitudinally. Exemption from the Columbia University Institutional Review Board was obtained.

Cohort Selection

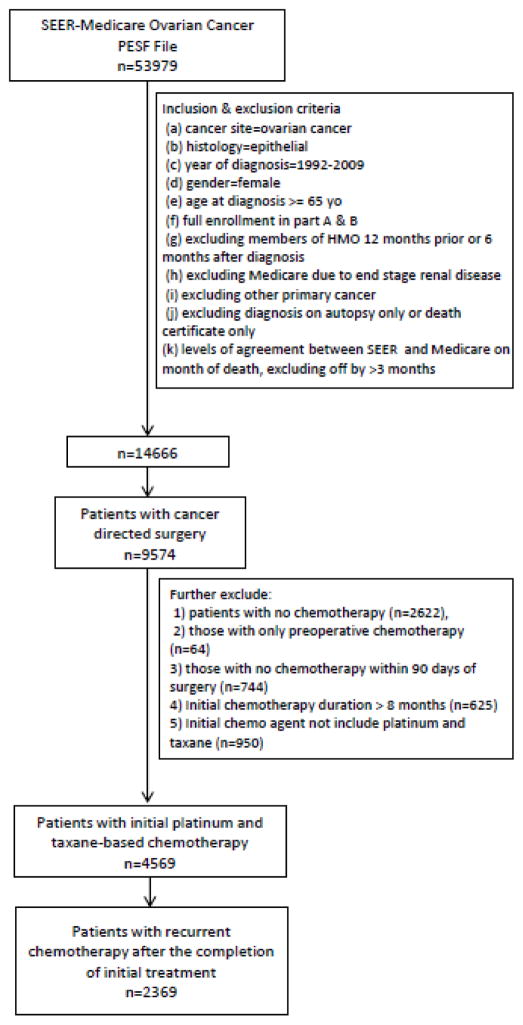

Women aged 65 years or older with epithelial ovarian cancer were selected. Patients who were diagnosed between January 1, 1992 and December 31, 2009, and received cancer directed surgery from one month before to within 6 months of diagnosis were included. The cohort was limited to women who underwent surgery for ovarian cancer and received combination platinum- and taxane-based chemotherapy after surgery. Patients may have received preoperative (neoadjuvant) chemotherapy in addition to postoperative chemotherapy. Patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy for more than 8 months were excluded. The study specifically focused on treatment of women with recurrent ovarian cancer. We therefore selected patients who initiated second line chemotherapy ≥3 months after completion of adjuvant treatment. Patients with incomplete claims, such as those who enrolled in a non-Medicare health maintenance organization, those receiving Medicare for a reason other than age, and patients with other primary cancers were excluded (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart for cohort selection.

Patient Characteristics

Age at diagnosis was stratified into 5-year intervals and race was recorded as white, black, and other. Marital status was recorded as married, not married, and unknown. An aggregate socioeconomic status (SES) score was calculated from education, poverty level, and income information from the 2000 census tract data, as previously reported by Du and co-workers.20 The SES scores were ranked on a scale of 1–5 by use of the formula that incorporated education, poverty, and income weighted equally, with 1 being the lowest value. The prevalence of comorbid medical diseases was assessed using the Klabunde adaptation of the Charlson comorbidity index (ie, the Klabunde–Charlson index).21,22 Medicare claims were examined for diagnostic codes of the International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM). Each condition was weighted, and patients were assigned a score that was based on the Klabunde–Charlson index.22 Area of residence was categorized as metropolitan or nonmetropolitan. The SEER registries were grouped as: Eastern, Western and Midwest. Stage was captured using the American Joint Cancer Commission staging criteria. Tumor histology was classified as serous, mucinous, endometrioid, clear cell or other. Tumor grade was grouped as well (1), moderately (2) or poorly differentiated, (3) or unknown.

Treatment and Outcomes

To identify ovarian cancer directed surgery and chemotherapy use, we extracted claims from the Medicare files by searching the Level II Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes, Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes, and ICD-9-CM diagnostic and procedure codes from Medicare provider and analysis review files, physician claims files, and the hospital outpatient claims files. In addition, revenue center codes were also added when querying chemotherapy data. Cancer directed surgery included any procedure claims for oophorectomy, hysterectomy, oophorectomy and debulking, exenteration, or debulking from 1 month before to 6 months after cancer diagnosis.

If a patient had any chemotherapy claims prior to cancer directed surgery, she was coded as having received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. If a patient had at least one claim for chemotherapy within 90 days of surgery, she was coded as having received postoperative chemotherapy. The duration of initial chemotherapy was calculated from the date of first chemotherapy claim after surgery through the date of last claim without a break of more than 3 months between any two claims. The duration of adjuvant chemotherapy was classified as 1–4, 5–6, and 7–8 months. If a patient had any chemotherapy claims at 3 or more months after the completion of first treatment, she was coded as having received second course of chemotherapy post-surgery. The interval from first to second chemotherapy course (platinum free interval, PFI) was categorized as ≤6, 7–12, and >12 months. The second course of chemotherapy was classified as single agent platinum if cisplatin, carboplatin or oxaliplatin were used alone. If a second agent was given concurrently, the patient was classified as having received platinum combination therapy. Receipt of any non-platinum containing single or multiagent regimen was considered as non-platinum chemotherapy. The primary outcome was survival. Survival was measured as the time from initiation of the second chemotherapy to death from any cause.

Statistical Analysis

Frequency distributions between categorical variables were compared using χ2 tests or Fisher’s exact test. Multivariable log-linear regression models were developed to determine predictors for the single agent and combination platinum-based second line chemotherapy. Separate models were developed for each platinum free interval group. The effect of the PFI on mortality and the effect of the chemotherapy regimens on mortality at each interval were examined using the method of Kaplan-Meier. Log-rank tests were used to compare the difference of survival curves. Cox proportional hazards models were developed to explore the association between second line chemotherapy and mortality while controlling for patients’ demographics and clinical covariates at each time interval. The proportional hazards assumption was tested by examining the scaled Schoenfeld model residuals, as well as by a visual inspection of the mortality curves among groups. All analyses were conducted with SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). All statistical tests were two-sided. A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

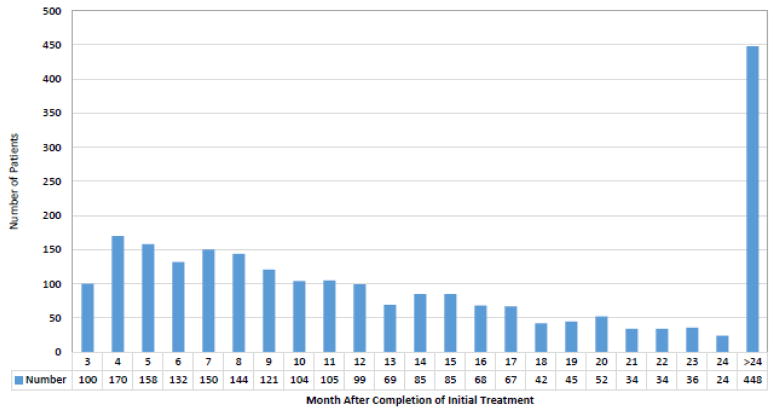

A total of 2,369 patients were identified. The cohort included 560 (23.6%) patients who restarted chemotherapy within 3–6 months, 723 (30.5%) who initiated therapy within 7–12 months, and 1086 (45.8%) who restarted treatment >12 months after their initial chemotherapy (Table 1). The median time from completion of adjuvant chemotherapy until initiation of second line chemotherapy was 12 months (IQR 7–20 months) (Figure 2). The majority of patients had advanced stage tumors (60.9% stage III and 25.6% stage IV) at the time of diagnosis.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the cohort stratified by platinum free interval.

| Total (n=2369) | 3–6 months (n=560) | 7–12 months (n=723) | >12 months (n=1086) | P-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | ||

| Demographics and clinical factors | |||||||||

| Age | 0.492 | ||||||||

| 65–69 | 662 | (27.9) | 164 | (29.3) | 199 | (27.5) | 299 | (27.5) | |

| 70–74 | 830 | (35) | 197 | (35.2) | 236 | (32.6) | 397 | (36.6) | |

| 75–79 | 589 | (24.9) | 137 | (24.5) | 188 | (26) | 264 | (24.3) | |

| >80 | 288 | (12.2) | 62 | (11.1) | 100 | (13.8) | 126 | (11.6) | |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.2573 | ||||||||

| White | 2,172 | (91.7) | 507 | (90.5) | 654 | (90.5) | 1,011 | (93.1) | |

| Black | 101 | (4.3) | 28 | (5) | 35 | (4.8) | 38 | (3.5) | |

| Other/Unknown | 96 | (4.1) | 25 | (4.5) | 34 | (4.7) | 37 | (3.4) | |

| Marital status | 0.0867 | ||||||||

| Married | 1,298 | (54.8) | 313 | (55.9) | 397 | (54.9) | 588 | (54.1) | |

| Unmarried | 1,015 | (42.8) | 235 | (42) | 300 | (41.5) | 480 | (44.2) | |

| Other | 56 | (2.4) | 12 | (2.1) | 26 | (3.6) | 18 | (1.7) | |

| Residence | 0.8456 | ||||||||

| Non-metropolitan | 227 | (9.6) | 56 | (10) | 71 | (9.8) | 100 | (9.2) | |

| Metropolitan | 2,142 | (90.4) | 504 | (90) | 652 | (90.2) | 986 | (90.8) | |

| Socioeconomic status | 0.3784 | ||||||||

| Lowest (first) quintile | 447 | (18.9) | 121 | (21.6) | 139 | (19.2) | 187 | (17.2) | |

| Second quintile | 491 | (20.7) | 106 | (18.9) | 141 | (19.5) | 244 | (22.5) | |

| Third quintile | 377 | (15.8) | 81 | (14.5) | 125 | (17.3) | 171 | (15.8) | |

| Fourth quintile | 565 | (23.8) | 133 | (23.8) | 179 | (24.8) | 253 | (23.3) | |

| Highest (fifth) quintile | 489 | (20.6) | 119 | (21.3) | 139 | (19.2) | 231 | (21.3) | |

| Registry area | 0.2041 | ||||||||

| Eastern | 518 | (21.9) | 111 | (19.8) | 174 | (24.1) | 233 | (21.5) | |

| Midwest | 923 | (39) | 217 | (38.8) | 289 | (40) | 417 | (38.4) | |

| West | 928 | (39.2) | 232 | (41.4) | 260 | (36) | 436 | (40.1) | |

| Diagnosis year | <.0001 | ||||||||

| 1993–1998 | 281 | (11.9) | 56 | (10) | 66 | (9.1) | 159 | (14.6) | |

| 1999–2004 | 1222 | (51.6) | 277 | (49.5) | 357 | (49.4) | 588 | (54.1) | |

| 2005–2009 | 866 | (36.6) | 227 | (40.5) | 300 | (41.5) | 339 | (31.2) | |

| Comorbidity Score | 0.5083 | ||||||||

| 0 | 1,650 | (69.6) | 383 | (68.4) | 497 | (68.7) | 770 | (70.9) | |

| 1 | 492 | (20.8) | 123 | (22) | 147 | (20.3) | 222 | (20.4) | |

| >/=2 | 227 | (9.6) | 54 | (9.6) | 79 | (10.9) | 94 | (8.7) | |

| Histology | 0.2778 | ||||||||

| Serous | 1,793 | (75.7) | 439 | (78.4) | 550 | (76.1) | 804 | (74) | |

| Endometrioid | 161 | (6.8) | 25 | (4.5) | 49 | (6.8) | 87 | (8) | |

| Clear Cell or Mucinous | 86 | (3.6) | 20 | (3.6) | 21 | (2.9) | 45 | (4.1) | |

| Other | 329 | (13.9) | 76 | (13.6) | 103 | (14.2) | 150 | (13.8) | |

| Stage | <.0001 | ||||||||

| I or II | 243 | (10.2) | 29 | (5.2) | 47 | (6.5) | 167 | (15.3) | |

| III | 1,443 | (60.9) | 331 | (59.1) | 456 | (63.1) | 656 | (60.4) | |

| IV | 607 | (25.6) | 185 | (33) | 196 | (27.1) | 226 | (20.8) | |

| Unknown | 76 | (3.2) | 15 | (2.7) | 24 | (3.3) | 37 | (3.4) | |

| Grade | 0.0016 | ||||||||

| 1 or 2 | 422 | (17.8) | 85 | (15.2) | 124 | (17.1) | 213 | (19.6) | |

| 3 | 1,573 | (66.4) | 386 | (68.9) | 454 | (62.8) | 733 | (67.5) | |

| Unknown | 374 | (15.8) | 89 | (15.9) | 145 | (20.1) | 140 | (12.9) | |

| Hospital Control | 0.2758 | ||||||||

| Nonprofit | 1,688 | (71.3) | 407 | (72.7) | 499 | (69) | 782 | (72) | |

| Private | 180 | (7.6) | 43 | (7.7) | 53 | (7.3) | 84 | (7.7) | |

| Government | 317 | (13.4) | 64 | (11.4) | 117 | (16.2) | 136 | (12.5) | |

| Unknown | 184 | (7.8) | 46 | (8.2) | 54 | (7.5) | 84 | (7.7) | |

| Hospital Bed Sizes | 0.1755 | ||||||||

| <400 | 1,194 | (50.4) | 282 | (50.4) | 337 | (46.6) | 575 | (52.9) | |

| 400–600 | 662 | (27.9) | 157 | (28) | 226 | (31.3) | 279 | (25.7) | |

| >600 | 329 | (13.9) | 75 | (13.4) | 106 | (14.7) | 148 | (13.6) | |

| Unknown | 184 | (7.8) | 46 | (8.2) | 54 | (7.5) | 84 | (7.7) | |

| Teaching Hospital | 0.0916 | ||||||||

| No | 558 | (23.6) | 151 | (27) | 159 | (22) | 248 | (22.8) | |

| Yes | 1,502 | (63.4) | 345 | (61.6) | 476 | (65.8) | 681 | (62.7) | |

| Unknown | 309 | (13) | 64 | (11.4) | 88 | (12.2) | 157 | (14.5) | |

| Initial treatment | <.0001 | ||||||||

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 294 | (12.4) | 89 | (15.9) | 116 | (16) | 89 | (8.2) | |

| Initial chemotherapy duration (months) | <.0001 | ||||||||

| 1 to 4 | 985 | (41.6) | 208 | (37.1) | 325 | (45) | 452 | (41.6) | |

| 5 to 6 | 1109 | (46.8) | 262 | (46.8) | 321 | (44.4) | 526 | (48.4) | |

| 7 to 8 | 275 | (11.6) | 90 | (16.1) | 77 | (10.7) | 108 | (9.9) | |

| Recurrent chemotherapy regimen | <.0001 | ||||||||

| Platinum combination | 1070 | (45.2) | 158 | (28.2) | 287 | (39.7) | 625 | (57.6) | |

| Platinum alone | 262 | (11.1) | 29 | (5.2) | 90 | (12.4) | 143 | (13.2) | |

| Non-platinum | 1037 | (43.8) | 373 | (66.6) | 346 | (47.9) | 318 | (29.3) | |

Figure 2.

Duration of platinum free interval between completion of adjuvant therapy and initiation of salvage therapy.

Early recurrences (PFI <6 months) were more frequent in women treated more recently, in women with higher stage tumors at diagnosis, in those treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and in patients with a longer duration of adjuvant chemotherapy (P<0.05 for all). In women with a PFI of ≤6 months, treatment consisted of platinum-based combination therapy in 28.2%, single agent platinum in 5.2% and non-platinum therapy in 66.6%. Corresponding rates of these treatments among women with a PFI of 7–12 months were 39.7%, 12.4% and 47.9% and 57.6%, 13.2% and 29.3% in those with a PFI of >12 months.

There were few consistent clinical and demographic characteristics associated with treatment received across the groups (Table 2). For women with a PFI of 7–12 or >12 months, none of the clinical, demographic or tumor characteristics were associated with platinum-based therapy. Among women with a PFI of ≤6 months, women treated more recently, those who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and patients whose adjuvant treatment lasted 5–6 months were less likely to receive platinum-based therapy (P<0.05 for all).

Table 2.

Predictors of use of platinum-based chemotherapy based on platinum free interval.

| 3–6 months | 7–12 months | >12 months | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Any Platinum | Platinum Combination | Any Platinum | Platinum Combination | Any Platinum | Platinum Combination | |

| RR (95%CI) | RR (95%CI) | RR (95%CI) | RR (95%CI) | RR (95%CI) | RR (95%CI) | |

| Age | ||||||

| 65–69 | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| 70–74 | 1.25 (0.85, 1.83) | 1.13 (0.75, 1.71) | 0.99 (0.76, 1.29) | 1.17 (0.87, 1.58) | 0.98 (0.82, 1.18) | 0.90 (0.74, 1.09) |

| 75–79 | 1.26 (0.83, 1.91) | 1.08 (0.68, 1.70) | 0.92 (0.69, 1.22) | 0.96 (0.69, 1.34) | 0.89 (0.72, 1.09) | 0.82 (0.66, 1.03) |

| ≥80 | 1.49 (0.89, 2.50) | 1.72 (1.01, 2.92)* | 1.01 (0.72, 1.41) | 0.95 (0.64, 1.43) | 1.02 (0.79, 1.31) | 0.80 (0.60, 1.06) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Black | 1.51 (0.80, 2.83) | 1.51 (0.76, 3.00) | 0.94 (0.57, 1.57) | 0.96 (0.55, 1.69) | 0.87 (0.57, 1.33) | 0.90 (0.57, 1.44) |

| Other/Unknown | 1.23 (0.65, 2.32) | 1.17 (0.57, 2.41) | 0.73 (0.42, 1.28) | 0.64 (0.33, 1.23) | 1.10 (0.75, 1.63) | 0.95 (0.60, 1.50) |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Unmarried | 0.93 (0.68, 1.26) | 0.86 (0.61, 1.20) | 1.12 (0.90, 1.39) | 1.21 (0.95, 1.55) | 1.00 (0.86, 1.16) | 1.00 (0.85, 1.18) |

| Other | 0.74 (0.23, 2.39) | 0.91 (0.28, 2.97) | 1.41 (0.84, 2.37) | 1.46 (0.79, 2.70) | 1.19 (0.71, 1.99) | 1.03 (0.56, 1.90) |

| Residence | Referent | Referent | ||||

| Non-metropolitan | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Metropolitan | 1.06 (0.61, 1.84) | 1.05 (0.58, 1.88) | 0.88 (0.62, 1.24) | 0.93 (0.63, 1.37) | 0.95 (0.73, 1.24) | 0.85 (0.64, 1.13) |

| Socioeconomic status | ||||||

| Lowest (first) quintile | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Second quintile | 0.96 (0.61, 1.53) | 0.94 (0.57, 1.55) | 1.29 (0.93, 1.78) | 1.34 (0.94, 1.92) | 0.97 (0.76, 1.23) | 0.98 (0.75, 1.27) |

| Third quintile | 0.75 (0.43, 1.31) | 0.72 (0.39, 1.32) | 1.03 (0.72, 1.48) | 0.99 (0.66, 1.48) | 1.00 (0.77, 1.31) | 0.98 (0.73, 1.31) |

| Fourth quintile | 0.79 (0.49, 1.27) | 0.80 (0.48, 1.32) | 0.98 (0.69, 1.38) | 0.84 (0.57, 1.26) | 1.00 (0.78, 1.29) | 1.01 (0.76, 1.33) |

| Highest (fifth) quintile | 1.02 (0.63, 1.64) | 0.91 (0.53, 1.54) | 1.04 (0.73, 1.50) | 0.90 (0.59, 1.36) | 1.04 (0.80, 1.35) | 0.98 (0.74, 1.31) |

| Registry area | ||||||

| Eastern | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Midwest | 1.37 (0.85, 2.21) | 1.49 (0.87, 2.54) | 1.21 (0.90, 1.63) | 1.21 (0.85, 1.72) | 1.13 (0.91, 1.40) | 1.05 (0.83, 1.33) |

| West | 1.65 (1.05, 2.59)* | 1.84 (1.11, 3.04)* | 1.30 (0.97, 1.75) | 1.38 (0.98, 1.95) | 1.05 (0.85, 1.28) | 1.05 (0.84, 1.32) |

| Diagnosis year | ||||||

| 1993–1998 | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| 1999–2004 | 0.63 (0.41, 0.97)* | 0.83 (0.50, 1.37) | 0.79 (0.56, 1.11) | 1.03 (0.66, 1.60) | 1.04 (0.84, 1.30) | 1.08 (0.84, 1.38) |

| 2005–2009 | 0.52 (0.33, 0.82)* | 0.68 (0.40, 1.14) | 0.78 (0.54, 1.11) | 1.18 (0.75, 1.86) | 1.11 (0.87, 1.40) | 1.20 (0.92, 1.56) |

| Comorbidity Score | ||||||

| 0 | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| 1 | 1.07 (0.74, 1.55) | 1.22 (0.80, 1.85) | 1.09 (0.83, 1.43) | 1.13 (0.83, 1.55) | 1.05 (0.87, 1.26) | 1.05 (0.86, 1.29) |

| ≥2 | 1.24 (0.69, 2.23) | 1.27 (0.67, 2.43) | 0.99 (0.66, 1.48) | 1.09 (0.69, 1.71) | 1.04 (0.78, 1.39) | 0.96 (0.69, 1.33) |

| Histology | ||||||

| Serous | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Mucinous | 1.24 (0.43, 3.60) | 1.50 (0.51, 4.36) | 1.07 (0.42, 2.70) | 1.41 (0.49, 4.00) | 0.79 (0.44, 1.42) | 0.79 (0.41, 1.51) |

| Endometrioid | 1.45 (0.78, 2.70) | 1.38 (0.69, 2.75) | 0.85 (0.54, 1.32) | 0.77 (0.45, 1.31) | 0.92 (0.70, 1.22) | 0.97 (0.71, 1.31) |

| Clear Cell | 1.26 (0.49, 3.23) | 1.63 (0.63, 4.25) | 0.95 (0.42, 2.15) | 1.06 (0.46, 2.45) | 1.18 (0.74, 1.87) | 1.26 (0.76, 2.08) |

| Other | 0.83 (0.53, 1.30) | 0.95 (0.59, 1.53) | 1.09 (0.82, 1.46) | 0.96 (0.68, 1.37) | 0.98 (0.79, 1.22) | 1.08 (0.85, 1.36) |

| Stage | ||||||

| I | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| II | 2.10 (0.41, 10.80) | 1.97 (0.37, 10.53) | 0.92 (0.43, 1.93) | 0.88 (0.38, 2.01) | 1.01 (0.70, 1.47) | 0.89 (0.59, 1.35) |

| III | 1.51 (0.32, 7.02) | 1.34 (0.28, 6.46) | 0.70 (0.37, 1.31) | 0.67 (0.33, 1.34) | 0.95 (0.70, 1.29) | 0.92 (0.66, 1.29) |

| IV | 1.69 (0.36, 7.98) | 1.68 (0.34, 8.17) | 0.72 (0.37, 1.38) | 0.69 (0.34, 1.43) | 0.93 (0.66, 1.30) | 0.95 (0.66, 1.36) |

| Unknown | 1.62 (0.27, 9.76) | 0.95 (0.13, 6.76) | 0.60 (0.25, 1.43) | 0.36 (0.12, 1.12) | 1.07 (0.67, 1.73) | 1.00 (0.59, 1.71) |

| Grade | ||||||

| 1 | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| 2 | 0.89 (0.29, 2.69) | 0.77 (0.25, 2.35) | 1.01 (0.47, 2.17) | 1.18 (0.45, 3.10) | 1.10 (0.66, 1.83) | 0.88 (0.53, 1.49) |

| 3 | 0.79 (0.27, 2.33) | 0.65 (0.22, 1.96) | 1.06 (0.51, 2.20) | 1.23 (0.49, 3.10) | 1.20 (0.74, 1.96) | 0.98 (0.60, 1.60) |

| Unknown | 0.81 (0.26, 2.50) | 0.72 (0.23, 2.26) | 1.03 (0.48, 2.19) | 1.31 (0.51, 3.39) | 1.18 (0.70, 1.99) | 0.99 (0.58, 1.69) |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | ||||||

| No | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Yes | 0.61 (0.38, 0.99)* | 0.62 (0.37, 1.04) | 0.98 (0.73, 1.32) | 0.95 (0.68, 1.34) | 0.97 (0.73, 1.29) | 0.82 (0.59, 1.14) |

| Initial chemotherapy duration (months) | ||||||

| 1 to 4 | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| 5 to 6 | 0.56 (0.40, 0.78)* | 0.53 (0.37, 0.75)* | 0.86 (0.68, 1.07) | 0.89 (0.69, 1.15) | 0.97 (0.83, 1.14) | 0.99 (0.83, 1.18) |

| 7 to 8 | 0.66 (0.42, 1.03) | 0.63 (0.39, 1.02) | 0.69 (0.47, 1.03) | 0.74 (0.47, 1.16) | 1.02 (0.79, 1.33) | 1.01 (0.75, 1.34) |

P<0.05,

P<0.0001

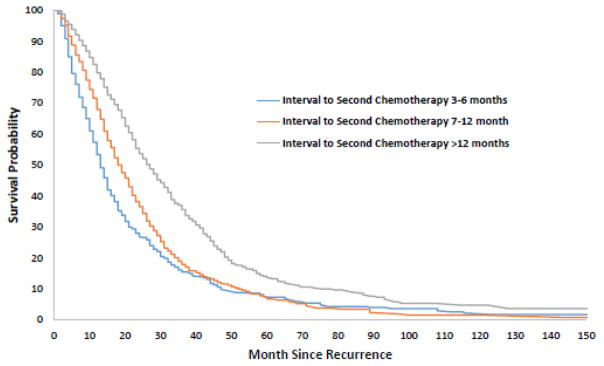

The median survival time for the cohort after initiation of second line chemotherapy was 21 months. Earlier recurrence was associated with decreased survival time. Median survival was 13, 18, and 27 months for patients with a PFI of ≤6 months, 7–12 months, and >12 months, respectively (P<0.0001) (Figure 3). For all three groups, platinum combination therapy was associated with decreased risk of death compared to non-platinum based therapy: HR=0.59 (95% CI, 0.48–0.74) for PFI ≤6 months, HR=0.75 (95% CI, 0.62–0.89) for PFI 7-12 months and HR=0.54 (95% CI, 0.47–0.63) for PFI >12 months (Table 3). For women with a PFI of >12 months, single agent platinum therapy was associated with a reduced risk of death compared to non-platinum based therapy (HR=0.75; 95% CI, 0.60–0.94). There was no statistically significant difference in survival between non-platinum and single agent platinum therapy for those with a PFI of ≤6 months and 7–12 months.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves of survival based on platinum free interval.

Table 3.

Cox proportional hazards models of predictors of survival based on platinum free interval.

| 3–6 months | 7–12 months | >12 months | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95%CI) | HR (95%CI) | HR (95%CI) | |

| Age | |||

| 65–69 | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| 70–74 | 1.03 (0.83, 1.29) | 0.99 (0.80, 1.22) | 1.25 (1.05, 1.50)* |

| 75–79 | 1.29 (1.01, 1.66)* | 1.22 (0.97, 1.52) | 1.56 (1.28, 1.89)** |

| ≥80 | 1.08 (0.78, 1.49) | 1.14 (0.87, 1.49) | 1.75 (1.37, 2.24)** |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Black | 0.93 (0.61, 1.43) | 0.98 (0.67, 1.43) | 0.87 (0.58, 1.32) |

| Other/Unknown | 0.90 (0.57, 1.43) | 0.72 (0.49, 1.06) | 0.89 (0.61, 1.31) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Unmarried | 1.07 (0.88, 1.30) | 0.94 (0.80, 1.11) | 1.11 (0.96, 1.27) |

| Other | 0.99 (0.51, 1.94) | 1.10 (0.72, 1.69) | 0.84 (0.47, 1.49) |

| Residence | |||

| Non-metropolitan | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Metropolitan | 1.15 (0.81, 1.62) | 1.07 (0.80, 1.43) | 0.83 (0.64, 1.07) |

| Socioeconomic status | |||

| Lowest (first) quintile | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Second quintile | 1.19 (0.88, 1.60) | 0.92 (0.71, 1.19) | 0.86 (0.69, 1.08) |

| Third quintile | 1.05 (0.76, 1.46) | 1.04 (0.79, 1.36) | 0.99 (0.77, 1.27) |

| Fourth quintile | 1.11 (0.83, 1.48) | 0.91 (0.70, 1.18) | 0.93 (0.73, 1.19) |

| Highest (fifth) quintile | 0.91 (0.67, 1.23) | 0.90 (0.69, 1.19) | 0.88 (0.68, 1.12) |

| Registry area | |||

| Eastern | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Midwest | 1.22 (0.94, 1.60) | 1.11 (0.90, 1.38) | 1.03 (0.84, 1.27) |

| West | 1.08 (0.83, 1.39) | 0.99 (0.80, 1.24) | 1.03 (0.85, 1.25) |

| Diagnosis year | |||

| 1993–1998 | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| 1999–2004 | 1.35 (0.99, 1.84) | 1.20 (0.91, 1.60) | 0.92 (0.76, 1.11) |

| 2005–2009 | 1.24 (0.90, 1.72) | 1.19 (0.88, 1.60) | 0.83 (0.66, 1.05) |

| Comorbidity Score | |||

| 0 | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| 1 | 1.00 (0.80, 1.25) | 0.96 (0.78, 1.17) | 1.06 (0.89, 1.25) |

| ≥2 | 1.29 (0.94, 1.76) | 1.16 (0.89, 1.51) | 1.33 (1.04, 1.71)* |

| Histology | |||

| Serous | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Mucinous | 5.08 (2.50, 10.32)** | 0.94 (0.46, 1.90) | 1.41 (0.85, 2.34) |

| Endometrioid | 0.71 (0.46, 1.11) | 1.20 (0.86, 1.68) | 0.79 (0.60, 1.04) |

| Clear Cell | 0.78 (0.41, 1.50) | 1.62 (0.87, 3.03) | 1.31 (0.81, 2.11) |

| Other | 1.09 (0.82, 1.43) | 1.08 (0.86, 1.37) | 1.07 (0.88, 1.31) |

| Stage | |||

| I | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| II | 1.86 (0.67, 5.14) | 0.51 (0.26, 0.99)* | 0.82 (0.56, 1.20) |

| III | 1.89 (0.75, 4.73) | 0.89 (0.52, 1.53) | 0.99 (0.73, 1.34) |

| IV | 2.17 (0.86, 5.46) | 1.11 (0.64, 1.92) | 1.07 (0.77, 1.49) |

| Unknown | 3.31 (1.14, 9.56)* | 1.00 (0.50, 1.97) | 1.09 (0.67, 1.75) |

| Grade | |||

| 1 | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| 2 | 1.03 (0.45, 2.33) | 0.86 (0.48, 1.54) | 0.85 (0.54, 1.34) |

| 3 | 0.95 (0.43, 2.09) | 0.86 (0.50, 1.50) | 0.95 (0.62, 1.45) |

| Unknown | 0.93 (0.41, 2.10) | 0.84 (0.47, 1.49) | 0.90 (0.57, 1.44) |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | |||

| No | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Yes | 1.62 (1.26, 2.08)* | 1.20 (0.95, 1.51) | 0.87 (0.66, 1.14) |

| Initial chemotherapy duration (months) | |||

| 1 to 4 | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| 5 to 6 | 1.01 (0.82, 1.24) | 0.99 (0.82, 1.18) | 0.98 (0.84, 1.14) |

| 7 to 8 | 1.34 (1.02, 1.77)* | 1.07 (0.81, 1.40) | 0.93 (0.72, 1.19) |

| Recurrent chemotherapy regimen | |||

| Non-platinum | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Platinum alone | 0.70 (0.47, 1.06) | 0.81 (0.63, 1.04) | 0.75 (0.60, 0.94)* |

| Platinum combination | 0.59 (0.48, 0.74)** | 0.75 (0.62, 0.89)* | 0.54 (0.47, 0.63)** |

P<0.05,

P<0.0001

Discussion

Among elderly women with ovarian cancer, the median survival time after initiation of second line chemotherapy is 21 months. Platinum free interval is a strong predictor of survival in this population. There is widespread variation in treatment selection for women with recurrent ovarian cancer with many women with platinum resistant disease receiving platinum-based therapy and likewise, many women with platinum sensitive disease are treated with non-platinum containing regimens.

Combination platinum and taxane therapy is the standard of care for primary therapy of epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal cancer.5,23,24 Treatment selection for recurrent cancers is partly dependent on whether the cancer is likely to be platinum-sensitive or platinum-resistant. Cancers that recur within 6 months after an initial treatment that included platinum, are considered platinum resistant.9 Recommended chemotherapy for these patients typically relies on non-platinum based therapy including single agent therapy with taxanes,25 topoisomerase inhibitors,26 the antimetabolite gemcitabine,27 or liposomal doxorubicin among other therapies. Conversely, patients with a recurrence after a platinum free interval of 6 months, are considered platinum-sensitive. Appropriate treatment in this circumstance is either a platinum combination regimen, or platinum alone if side effects are a concern.3,5,28,29

Our data supports previous findings of the association between the duration of initial PFI and outcomes after second line chemotherapy.30 In one of the initial studies of PFI, Markman and colleagues reported response rates of <30% in patients with a PFI of 12 months or less compared to a response rate of 59% in those with a PFI of >24 months7. While we are unable to assess response rates, among elderly women with ovarian cancer survival increased with the duration of PFI from 13 months in those with a PFI of <6 months to 27 months in women with a PFI of >12 months.

Like prior studies, we noted widespread variation in treatment for relapsed ovarian cancer.10,31 Nearly one-third of the patients in our cohort with likely platinum-sensitive cancers did not receive platinum, and one-third of patients with likely platinum-resistant cancers were retreated with platinum. Platinum use for patients with platinum-resistant cancers has the potential to increase adverse effects without improving clinical response to treatment.32 In our analysis, there were few predictors of non-guideline based treatment. Further study to identify factors associated with non-guideline based care is clearly needed. Prior studies for ovarian cancer have found that patients treated by high volume surgeons and at high volume centers are more likely to receive guideline-based care.33,34

We noted that treatment with platinum-based therapy was associated with improved survival for women with recurrent ovarian cancer.30 For women with a PFI of >12 months, platinum retreatment was associated with a 25–46% reduction in mortality compared to non-platinum based therapy. These data confirm that in elderly women, platinum-based combination therapy is superior to single agent platinum therapy.28 Interestingly, we also noted that survival in women with platinum resistant ovarian cancer was superior with platinum-based therapy compared to non-platinum based regimens. While these results are likely influenced by some degree of selection bias, this finding warrants further study. There has been some evidence of the utility of re-treating with platinum in platinum resistant patients.35–38

While our study benefits from the inclusion of a large number of women, we recognize a number of important limitations. First, chemotherapy use may have been under captured or the platinum free interval miscalculated in a small number of patients. Our data relies on billing claims and is thus subject to some variability in capture. We relied on the date of initiation of second line chemotherapy as opposed to the date of diagnosis of recurrence to calculate the platinum free interval. This is an intrinsic limitation of the dataset. Second, our analysis is limited to elderly women and as such, these findings may be different in younger women. Third, we only included women with recurrent disease who were treated with salvage chemotherapy thus our sample represents a somewhat selected population. While the goal of our analysis was to examine outcomes in women treated with chemotherapy, we acknowledge that there are likely many women who recurred and did not receive treatment. Fourth, while we adjusted for a number of clinical, demographic, and pathologic characteristics, there are likely a number of unmeasured confounders such as performance status, residual tumor burden, and residual toxicity that we could not account for that likely influenced treatment decision making and outcomes. Finally, our study spanned several years in which available treatment options for ovarian cancer evolved. During this time the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy became more widespread and a number of new therapeutic options were introduced for recurrent ovarian cancer. All of these factors could have influenced our findings.

In conclusion, we noted widespread variation in the patterns of care of women with recurrent ovarian cancer. Our results support an association between platinum free interval and overall survival. We found that non-guideline based treatment was common, but there were few identifiable significant predictors for this. These findings have a number of implications for the care of women with ovarian cancer. First, further study is warranted to identify factors affecting chemotherapy selection choice outside of standard guidelines for recurrent ovarian cancer. More importantly, initiatives are needed to promote adherence to evidence-based recommendations for women with recurrent ovarian cancer.

Research Highlights.

Platinum free interval is a strong predictor of survival in elderly women with recurrent ovarian cancer.

There is widespread variation in treatment selection for women with recurrent ovarian cancer.

Many women receiving non-guideline based regimens.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Wright has served as a consultant for Tesaro and Clovis Oncology. Dr. Neugut has served as a consultant to Pfizer, Teva, Otsuka, and United Biosource Corporation. He is on the medical advisory board of EHE, Intl. No other authors have any conflicts of interest or disclosures.

Dr. Wright (NCI R01CA169121-01A1) and Dr. Hershman (NCI R01 CA166084) are recipients of grants from the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Hershman is the recipient of a grant from the Breast Cancer Research Foundation/Conquer Cancer Foundation. Dr. Tergas is a recipient of an NCI Diversity Supplement (CA197730).

This study used the linked SEER-Medicare database. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibility of the authors. The authors acknowledge the efforts of the National Cancer Institute; the Office of Research, Development and Information, CMS; Information Management Services (IMS), Inc.; and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER-Medicare database.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Salani R, Backes FJ, Fung MF, et al. Posttreatment surveillance and diagnosis of recurrence in women with gynecologic malignancies: Society of Gynecologic Oncologists recommendations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:466–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Modesitt SC, Jazaeri AA. Recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer: pharmacotherapy and novel therapeutics. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2007;8:2293–305. doi: 10.1517/14656566.8.14.2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fung-Kee-Fung M, Oliver T, Elit L, Oza A, Hirte HW, Bryson P. Optimal chemotherapy treatment for women with recurrent ovarian cancer. Curr Oncol. 2007;14:195–208. doi: 10.3747/co.2007.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poveda AM, Selle F, Hilpert F, et al. Bevacizumab Combined With Weekly Paclitaxel, Pegylated Liposomal Doxorubicin, or Topotecan in Platinum-Resistant Recurrent Ovarian Cancer: Analysis by Chemotherapy Cohort of the Randomized Phase III AURELIA Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3836–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.NCCN. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®): Ovarian Cancer Including Fallopian Tube Cancer and Primary Peritoneal Cancer. Version 2.2015. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pujade-Lauraine E. How to approach patients in relapse. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(Suppl 10):x128–31. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Markman M, Rothman R, Hakes T, et al. Second-line platinum therapy in patients with ovarian cancer previously treated with cisplatin. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9:389–93. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.3.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gadducci A, Fuso L, Cosio S, et al. Are surveillance procedures of clinical benefit for patients treated for ovarian cancer?: A retrospective Italian multicentric study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19:367–74. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181a1cc02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedlander M, Trimble E, Tinker A, et al. Clinical trials in recurrent ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21:771–5. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e31821bb8aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dinkelspiel HE, Tergas AI, Zimmerman LA, et al. Use and duration of chemotherapy and its impact on survival in early-stage ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;137:203–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wright J, Doan T, McBride R, Jacobson J, Hershman D. Variability in chemotherapy delivery for elderly women with advanced stage ovarian cancer and its impact on survival. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:1197–203. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wright JD, Burke WM, Tergas AI, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Minimally Invasive Hysterectomy for Endometrial Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1087–96. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.3212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wright JD, Burke WM, Wilde ET, et al. Comparative effectiveness of robotic versus laparoscopic hysterectomy for endometrial cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:783–91. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.7508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wright JD, Herzog TJ, Neugut AI, et al. Effect of radical cytoreductive surgery on omission and delay of chemotherapy for advanced-stage ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:871–81. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31826981de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wright JD, Neugut AI, Wilde ET, et al. Physician characteristics and variability of erythropoiesis-stimulating agent use among Medicare patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3408–18. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.5462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wright JD, Tergas AI, Hou JY, et al. Trends in Periodic Surveillance Testing for Early-Stage Uterine Cancer Survivors. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:449–58. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burger RA, Sill M, Monk BJ, Greer B, Sorosky J. Phase II trial of bevacizumab in persistent or recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) or primary peritoneal cancer (PPC): a Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) study. Proceedings of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2005 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.5345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Potosky AL, Riley GF, Lubitz JD, Mentnech RM, Kessler LG. Potential for cancer related health services research using a linked Medicare-tumor registry database. Med Care. 1993;31:732–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Schrag D, Bach PB, Riley GF. Overview of the SEER-Medicare data: content, research applications, and generalizability to the United States elderly population. Med Care. 2002;40:IV-3–18. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000020942.47004.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Du XL, Fang S, Vernon SW, et al. Racial disparities and socioeconomic status in association with survival in a large population-based cohort of elderly patients with colon cancer. Cancer. 2007;110:660–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charlson ME, Sax FL, MacKenzie CR, Fields SD, Braham RL, Douglas RG., Jr Assessing illness severity: does clinical judgment work? J Chronic Dis. 1986;39:439–52. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(86)90111-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Legler JM, Warren JL. Development of a comorbidity index using physician claims data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:1258–67. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00256-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kyrgiou M, Salanti G, Pavlidis N, Paraskevaidis E, Ioannidis JP. Survival benefits with diverse chemotherapy regimens for ovarian cancer: meta-analysis of multiple treatments. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1655–63. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Webber K, Friedlander M. Chemotherapy for epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube and primary peritoneal cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gynecologic Oncology G. Markman M, Blessing J, et al. Phase II trial of weekly paclitaxel (80 mg/m2) in platinum and paclitaxel-resistant ovarian and primary peritoneal cancers: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;101:436–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rose PG, Blessing JA, Mayer AR, Homesley HD. Prolonged oral etoposide as second-line therapy for platinum-resistant and platinum-sensitive ovarian carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:405–10. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.2.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mutch DG, Orlando M, Goss T, et al. Randomized phase III trial of gemcitabine compared with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2811–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.6735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parmar MK, Ledermann JA, Colombo N, et al. Paclitaxel plus platinum-based chemotherapy versus conventional platinum-based chemotherapy in women with relapsed ovarian cancer: the ICON4/AGO-OVAR-2. 2 trial. Lancet. 2003;361:2099–106. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13718-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pfisterer J, Plante M, Vergote I, et al. Gemcitabine plus carboplatin compared with carboplatin in patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer: an intergroup trial of the AGO-OVAR, the NCIC CTG, and the EORTC GCG. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4699–707. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.0913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Markman M, Markman J, Webster K, et al. Duration of response to second-line, platinum-based chemotherapy for ovarian cancer: implications for patient management and clinical trial design. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3120–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goff BA, Matthews BJ, Wynn M, Muntz HG, Lishner DM, Baldwin LM. Ovarian cancer: patterns of surgical care across the United States. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;103:383–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lortholary A, Largillier R, Weber B, et al. Weekly paclitaxel as a single agent or in combination with carboplatin or weekly topotecan in patients with resistant ovarian cancer: the CARTAXHY randomized phase II trial from Groupe d’Investigateurs Nationaux pour l’Etude des Cancers Ovariens (GINECO) Ann Oncol. 2012;23:346–52. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cliby WA, Powell MA, Al-Hammadi N, et al. Ovarian cancer in the United States: contemporary patterns of care associated with improved survival. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136:11–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bristow RE, Chang J, Ziogas A, Randall LM, Anton-Culver H. High-volume ovarian cancer care: survival impact and disparities in access for advanced-stage disease. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;132:403–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Burg ME, de Wit R, van Putten WL, et al. Weekly cisplatin and daily oral etoposide is highly effective in platinum pretreated ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:19–25. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharma R, Graham J, Mitchell H, Brooks A, Blagden S, Gabra H. Extended weekly dose-dense paclitaxel/carboplatin is feasible and active in heavily pre-treated platinum-resistant recurrent ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:707–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rose PG. Gemcitabine reverses platinum resistance in platinum-resistant ovarian and peritoneal carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2005;15(Suppl 1):18–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2005.15357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Markman M, Kennedy A, Webster K, Kulp B, Peterson G, Belinson J. Evidence that a “treatment-free interval of less than 6 months” does not equate with clinically defined platinum resistance in ovarian cancer or primary peritoneal carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1998;124:326–8. doi: 10.1007/s004320050177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]