Abstract

A precision medicine approach is appealing for use in AML due to ease of access to tumor samples and the significant variability in the patients’ response to treatment. Attempts to establish a precision medicine platform for AML, however, have been unsuccessful, at least in part due to the use of small compound panels and having relatively slow turn over rates, which restricts the scope of treatment and delays its onset. For this pilot study, we evaluated a cohort of 12 patients with refractory AML using an ex vivo drug sensitivity testing (DST) platform. Purified AML blasts were screened with a panel of 215 FDA-approved compounds and treatment response was evaluated after 72h of exposure. Drug sensitivity scoring was reported to the treating physician, and patients were then treated with either DST- or non-DST guided therapy. We observed survival benefit of DST-guided therapy as compared to the survival of patients treated according to physician recommendation. Three out of four DST-treated patients displayed treatment response, while all of the non-DST-guided patients progressed during treatment. DST rapidly and effectively provides personalized treatment recommendations for patients with refractory AML.

Keywords: Acute Myeloid Leukemia, Ex-vivo Sensitivity Screening, Precision Medicine

Introduction

The concept of patient-specific drug sensitivity screening is not a new approach to personalized therapy. Indeed, it has been utilized to assign antibiotic and antifungal treatments for decades (1–3). Nevertheless, phenotypic screens evaluating drug sensitivity have only recently come into vogue in the cancer research community as part of precision medicine initiatives (4–12). Although these screenings can be theoretically performed for all cancers, the ability to do so is often hampered by the large number of cells needed for an ex vivo screen, the high intra-tumoral heterogeneity, and the lack of availability of tumor biopsies at the time of therapeutic need. Efforts have therefore concentrated on liquid cancers such as Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML), where large numbers of cancer blasts can be obtained through bone marrow (BM) biopsies or peripheral blood draws (7, 8). Furthermore, AML incidence has been increasing by 3.4% each year over the last 10 years and the overall 5-year survival of AML patients has remained low at ~26%, despite extensive research efforts (13). This low survival rate is primarily due to the fact that the standard regimen of chemotherapy (3+7 chemotherapy consisting of the nucleoside analog cytarabine combined with a topoisomerase II inhibitor) is not effective in the long term, with patients showing initial treatment response but quickly relapsing and succumbing to the disease. Thus, AML is a target of particular interest due to its liquid nature and ineffectiveness of current treatments.

Large scale sequencing projects have revealed a number of potential AML driver genes, including NPM1, CEBPA, DNMT3A, TET2, RUNX1, ASXL1, IDH2, and MLL, and have identified critical mutations in FLT3, IDH1, KIT, and RAS that result in significant changes in disease progression and drug sensitivity (14–17). These studies also highlighted high levels of heterogeneity with a single patient and showed rapid adaptation to chemotherapy treatments (14–17), suggesting that precision medicine targeting these genetic mutations might well improve outcomes over the currently available treatments. Although a number of these variants are targetable, very few treatments have been translated to the clinical practice.

Ex vivo drug sensitivity testing (DST) of clinically-available FDA-approved compounds that can be repurposed for off-label use provides a means to rapidly identify and clinically apply personalized therapies for AML patients with refractory disease (7, 8). The study presented here evaluates the clinical benefit of DST-guided therapy in patients with refractory AML in a small pilot population as compared to a cohort of patients that were evaluated by DST but treated based on non-DST-guided therapy. Treatment sensitivity towards 215 FDA-approved and investigational anti-cancer compounds was evaluated in a total of 12 AML samples, 4 of which were then treated based on the DST results.

Materials and methods

Patients

Patients with relapsed and/or refractory AML were eligible if no alternative life prolonging therapy was available. Other inclusion criteria included: age of at least 18 years; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0–2 and adequate organ function. Exclusion criteria included: pregnancy or breastfeeding; uncontrolled inter-current illness and known infection with HIV and/or viral hepatitis B or C. The study was approved by the University of Miami institutional review board (protocol number 20060858), and conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Written consent was obtained from all patients. Personalized treatment plans were reviewed by an institutional personalized therapeutics committee, which issued final treatment recommendations.

Workflow

For DST-guided therapy, bone marrow aspirates were obtained and AML blasts isolated by Ficoll density gradient (Ficoll-Paque PREMIUM; GE Healthcare) (18). Cells were washed, counted, and cultured in Mononuclear Cell Medium (MCM, PromoCell) for 24h. Ex vivo drug screening was carried out to identify potentially active agents. Screening results were collected and analyzed within 7–10 days of bone marrow sampling and personalized treatment plans were generated and submitted for review by our institutional personalized therapeutics committee (Supplementary Fig 1). Once DST-guided therapy was assigned, treatment continued until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity occurred.

For non-DST-guided therapy, ex vivo drug sensitivity screening was performed as described for DST-guided therapy. Screening results were collected and analyzed within 7–10 days of bone marrow sampling but results were not transmitted for clinical use. Patients were evaluated by the treating physician and therapy was assigned.

Compound Library

A range of FDA/EMA (Food and Drug Administration/European Medicines Agency) approved anti-cancer compounds (n=203) and investigational compounds (n=12) were represented in the compound library covering a variety of targets and pathways relevant to AML (Supplementary Table 1). The compounds were obtained from the National Cancer Institute Drug Testing Program (NCI DTP) and commercial vendors (Active Biochem, Axon Medchem, Cayman Chemical Company, ChemieTek, Enzo Life Sciences, LC Laboratories, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Selleck Chemicals, Sequoia Research Products, Sigma-Aldrich, Tocris Biosciences).

Ex vivo Sensitivity Profiling

Ex vivo sensitivity profiling was performed on freshly isolated or previously viably frozen primary AML blasts derived from patient bone marrow aspirates and mononuclear cells derived from healthy donors. Bone marrow aspirates or peripheral blood was obtained and AML blasts isolated by Ficoll density gradient (Ficoll-Paque PREMIUM; GE Healthcare) as described previously (18). All compounds were dissolved in 100% DMSO and tested in duplicate using a 10-point 1:3 dilution series starting at a nominal test concentration of 10 μM (20,000-fold concentration range). 1000 patient-derived mononuclear cells were seeded per well in 384-well micro-titer plates and incubated in the presence of compounds in a humidified environment at 37°C and 5% CO2. After 72 hours of treatment, cell viability was assessed by measuring ATP levels via bioluminescence (CellTiter-Glo, Promega) and dose response curves were generated for each compound. Each patient screen was quality controlled prior to scoring. Assays were considered valid only when the Z′-factor was equal to or greater than 0.5 (Z′ ≥ 0.5). The Z′-factor is a dimensionless statistical metric that is used for assessing the suitability of an assay for screening, whereby a Z′-factor ≥ 0.5 is considered to be excellent (7). Additionally, the percent coefficient of variation (% CV) for each plate, using positive and negative controls, had to be less than 20% to identify hits with a high degree of confidence.

Selective Sensitivity Scoring of Screened Drugs

The drug sensitivity scoring (DSS) function, originally developed by Yadav et al. (7), was implemented with several modifications, similar to the approach suggested by Pemovska et al. (8). Briefly, dose response data for each compound in the cell viability screen were fitted to a three-parameter nonlinear regression according to the formula:

where y was % cell death at concentration x, Top was the maximal effect of the drug (allowed to float between 0% and 100%), EC50 was the concentration at half maximal effect, and HillSlope was the slope of the curve. The relevant area under the curve (rAUC) was calculated by integrating the dose response curve starting at the threshold concentration where the response crosses 10% (xt) according to:

where xmax was the maximal concentration in the screen. The drug response area (DRA) was calculated according to the formula DRA = rAUC – tArea, where tArea was the portion of rAUC lying below the 10% threshold. The modified drug sensitivity score (DSSmod) was calculated according to the formula:

where MRA was the maximum possible drug response calculated as MRA = (max effect - threshold effect)(xmax – xmin), and xmin was the lowest screening concentration. The term served as a scaling function that penalized the scores of compounds failing to reach an effect of 100% cell death over the tested dose range. Finally, the selective DSSmod (sDSSmod) for each drug in each patient screen was calculated according to the formula sDSSmod = DSSmod (patient cells) - DSSmod (normal bone marrow mononuclear cells). Given in this way, the sDSSmod incorporated information on each drug’s potency, efficacy, effect range and therapeutic index, making it possible to prioritize compounds over multiple clinically relevant parameters using a single numerical metric. In addition, this methodology allowed us to rank compounds by leukemia-selective efficacy for each individual patient. For example, a large positive sDSSmod meant that a compound was highly selective for leukemic blasts in a given sample (favorable scenario), but a large negative score meant that the effect was preferential for normal cells (unfavorable scenario). All calculations and scoring routines were implemented in MatLab (2013b and 2016b, Curve Fitting and Statistics Toolboxes). Additional curve fitting and statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad prism (5.03).

Molecular/Genetic Profiling and Generation of Patient Specific Avatars

Whole exome sequencing and array CGH were performed on AML blasts derived from bone marrow aspirates. This information, entered into predictive computational biology software (Cellworks Group), generated patient-specific protein network maps using PubMed and other online resources. Digital drug simulations are conducted by measuring drug effect on a composite score of cell proliferation, viability and apoptosis. Each patient-specific network map was digitally screened for compound-reduced progression in a dose-responsive manner. Computer predictions were blindly correlated with ex vivo screening outcomes. The computational biology modeling platform consisted of three layers: the first layer was a proprietary mathematics solver engine constructed to handle millions of differential equations representing the crosstalk interactions needed for modeling AML biology, the middle layer was a comprehensive functional proteomics representation of disease physiology networks and the topmost layer was a semiconductor engineering-based automation engine, allowing high-throughput simulations of a variety of drug combinations.

RESULTS

Patients

A total of 12 patients were recruited to this pilot study (Table 1 & 2). The median age of the patients was 56 (range 21 – 81 years) and the median number of prior therapies was 3. 4/12 patients were selected for DST-directed therapy and 8/12 patients were treated with physician-directed therapy. All patients were analyzed by conventional G-band karyotyping, FISH, array CGH, and targeted sequencing for AML relevant genes as part of the clinical routine (Table 1 & 2). Additionally, two patients with high blast counts were selected for whole exome sequencing in an attempt to contextualize the ex vivo drug sensitivity screening using patient specific protein network map projections. AML blasts derived from patient 8 were tested but failed quality control due to a high variability observed in positive and negative controls within the assay. The patient was excluded from the DST arm.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics: DST-guided therapy.

| Patient | Age | Number of Prior Therapies | Cytogenetics | Driver Mutations | DST-guided therapy | Time to therapy (days) | Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 50 | 5 | 47 XX, +8 | FLT3-ITD | Bortezomib | 10 | Yes* |

| 3 | 40 | 8 | 45 XX, −7, del(5q) | NRAS | Gemcitabine | 7 | No# |

| 4 | 28 | 3 | 46, XX | FLT3-ITD, ASXL1, sCEBPA, WT1 | Azacitidine plus belinostat | 7 | Yes** |

| 5 | 21 | 3 | Complex karyotype | p53 | Vincristine plus dexamethasone | 14 | Yes* |

| 10 | 46 | 3 | t(8;21) | AML1-ETO | Nilotinib | 14 | No## |

Did not meet working group criteria for response,

Complete remission (CR),

Patient progressed prior to therapy start; had decrease in peripheral blasts but persistent AML on gemcitabine,

Patient progressed on DST-therapy.

Table 2.

Patient Demographics: Non-DST-guided therapy.

| Patient | Age | Number of Prior Therapies | Cytogenetics | Driver Mutations | Non-DST-guided therapy | Time to therapy (days) | Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 48 | 7 | 46, XX | FLT3-ITD, RUNX1, SF3B1 | Clinical Trail | 14 days | No |

| 6 | 79 | 1$ | 45 XY, −7 | DNMT3A, EZH2, RUNX1 | Palliative Care | n/a | No |

| 7 | 77 | 2 | 46, XY | sCEBPA, CSF3R, TET2 | Decitabine | 14 days | No |

| 8 | 54 | 4 | Complex karyotype | TP53 | Salvage chemotherapy and DLI | 7 days | No |

| 11 | 68 | 3 | Complex karyotype | TP53 | Clinical Trial | 21 days | No |

| 12 | 66 | 3 | 46, XY | NPM1, DNMT3A, KIT | Clinical Trial | 21 days | No |

Decitabine, not candidate for intensive therapy

Ex-vivo sensitivity testing

Bone marrow or peripheral blood samples from 12 patients with refractory AML were collected, AML blasts isolated (Supplementary Table 4) and cultured for 24 hours. Samples were incubated with FDA-approved compounds (Supplementary Table 1) and cell viability was measured after 72h. Individual drugs were tested over a 20,000-fold concentration range to generate dose response curves. Since interpretation of curve parameters was complex and cumbersome, we used a modified version of the Drug Sensitivity Score (DSSmod) reported by Pemovska et al. (8), to assess overall drug responses. The DSSmod incorporates information on drug potency, efficacy, effect range and therapeutic index, making it possible to rank compounds over multiple clinically relevant parameters. We also measured the AML-specific effect of each compound with a selective Drug Sensitivity Score (sDSSmod), which was calculated by further correcting the DSSmod for primary tumor samples with the DSSmod for control cells for each compound. As such, a large positive sDSSmod score indicates selective activity towards AML blasts compared to normal bone marrow cells.

In order to evaluate the consistency of treatment response between different plates, three compounds, namely gemcitabine, fluradabine and idarubicin, were tested in duplicate on different plates. While the DSSmod values were not identical, sDSSmod values were similar across all three plates (Supplementary Fig. 2).

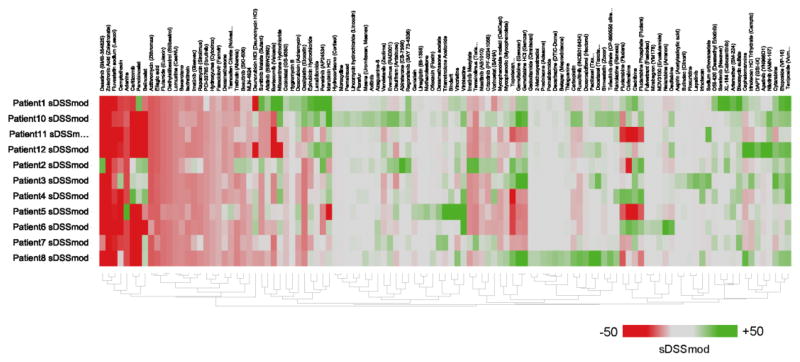

Consistent with previous studies, we observed high variability in drug responses across all samples tested (Fig 1). More than half of the compounds tested were not active in any of the tested cells. Of the compounds that did elicit a response, many induced cell death in heathy cells and consequently were not viable treatments. Also, there were a few compounds that seemed to be effective in targeting primary cells in several patients, such as Teriposide, Etoposide, and Bleomycin Sulfate, suggesting that this sort of analysis done in a larger population might also refine effective treatments for AML in general.

Figure 1. Ex vivo drug sensitivity screen.

The heatmap of sDSSmod profiles reveals large variability in both direction and magnitude of drug responses in the 7 AML patients tested. The sDSSmod profile for each patient is depicted with all drugs that had a score of more than +5 or less than −5 in at least one patient (drugs that had no effect in all patients were excluded). Patients and drugs were clustered using hierarchical clustering with a tanimoto distance metric. Green color indicates a positive sDSSmod score while red color indicates a negative sDSSmod score.

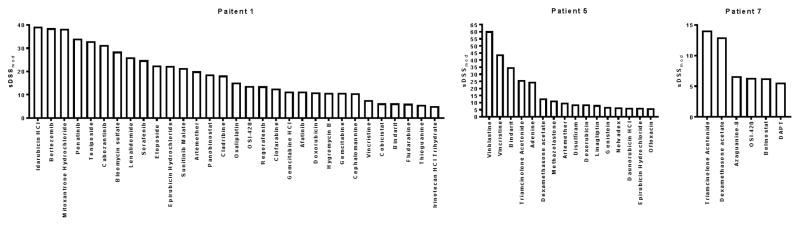

For the most part, however, individual patients displayed quite different drug sensitivity profiles (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 2). The number of viable drug candidates varied from 4 in patient 11 to 47 in patient 10. None of the tested compounds displayed activity in all 12 patients, and some had significantly different patient-specific activity, such as Ponatinib and Gemcitabine. Gemcitabine, for example, was the top candidate in patients 3 and 8 (sDSSmod 38.37 and sDSSmod 50.63, respectively), but showed no activity in patients 4, 5, 6, 7, 11,12.

Figure 2. Individual screening results.

Bar graphs of clinically actionable drug responses for patients 1, 6 and 7.

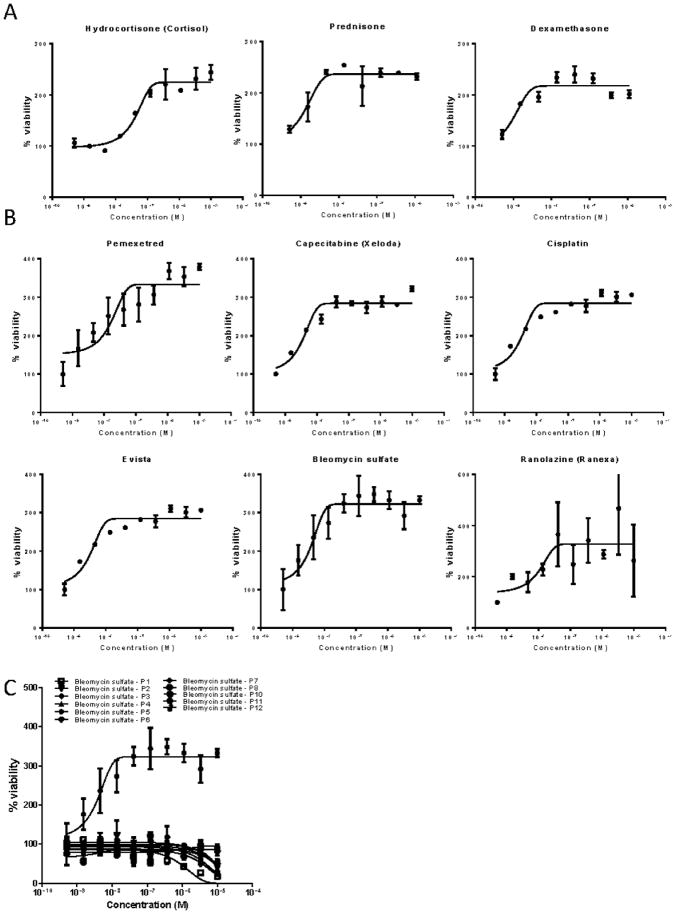

In addition to identifying potentially effective drugs for individual therapy, the assay was also able to identify agents that increased proliferation of AML blasts (Fig 3). Patient 3 demonstrated a marked increase in AML blast proliferation in response to treatment with steroids (dexamethasone, prednisone and hydrocortisone) (Fig 3A). Patient 6 displayed an increase in proliferation in response to 6 different agents (pemetrexed, capecitabine, cisplatin, raloxifene, bleomycin and ranolazine (Fig 3B). This increased proliferation response again varied between individuals, as illustrated in Figure 3C, which displays the response of all tested patients to treatment with bleomycin, showing a differential response in patient 6.

Figure 3. Patient specific induction of AML blast proliferation in response to treatment.

(A) Treatment with steroids (dexamethasone, prednisone and hydrocortisone) increased the proliferation of AML blasts obtained from patient 3. (B) Patient 6 displayed an increase in proliferation in response to treatment with pemetrexed, capecitabine, cisplatin, raloxifene, bleomycin and ranolazine. (C) While bleomycin significantly reduced AML blast survival when compared to normal bone marrow in the majority of patients (6/7); patient 6 displayed a dramatic dose-dependent increase in AML blast proliferation in response to treatment.

Patient Specific Protein Network Map Projections

Whole exome sequencing was used in two of the seven patient samples to validate the results of the ex vivo drug sensitivity screens. Using the genomic data, we generated patient-specific protein network maps of their dominant AML clones (Supplementary Fig 5). Next, the computational models of each patient’s AML blasts were digitally treated with a library of over 80 FDA-approved agents (Supplementary Table 3). The top performing drug combinations were identified based on quantitative reductions in simulated cancer growth score.

In the case of patient 1, cytogenetic and mutational analysis revealed an additional copy of chromosome 8 (47 XX, +8) and a FLT3 internal tandem duplication (internal tandem duplication (ITD) PCR yielded a PCR product of 393 base pairs) (Table 1). The computational model mapped numerous additional gene copy number variations and mutations that predicted overactivation of several signaling pathways, including PI3K, SYC, LYN, WNT, RAS and STAT signaling, all of which converge on increased cell proliferation and viability. Furthermore, the model also predicted impaired epigenetic regulation by DNMTs. Iterative digital drug simulations predicted three potentially active drug combinations: ponatinib and rosuvastatin, ponatinib and trametinib and ponatinib and decitibine (Supplementary Fig 5A). The tyrosine kinase receptor inhibitor ponatinib was identified as a potent compound in both the ex vivo drug sensitivity screen and the pathway analysis. The additional compounds suggested by the pathway analysis, however, were not tested in the drug sensitivity screen.

There was not always agreement between the computational models and ex vivo testing, however. For patient 5, gene mutational analysis revealed mTOR pathway defects in several negative regulators including PTEN, TP53, TSC2 and IRS2. The computational model suggested combined treatment with the mTOR inhibitor everolimus and the kinase inhibitor sorafenib (Supplementary Fig 5B), but neither compound displayed any significant AML specific activity in the ex vivo assay, suggesting that genetic screening should be used in concert with ex vivo drug sensitivity screens.

Clinical implementation

In order to evaluate accuracy of the DST treatment predictions, patients were selected to either receive DST-guided or non-DST-guided therapy. In cases of DST-guided therapy, the screening results forwarded to the treating physician. Treatment outcome and time elapsed until treatment start where evaluated for all patients (Table 1 & 2).

For patients selected for DST-guided therapy, the assay results were communicated to the PTC and compounds chosen based on the PTC recommendation. DST results were considered therapeutically actionable if: (1) proposed agents were available for compassionate or off-label use; (2) the proposed therapy did not significantly delay the patient’s ability to get treated and; (3) no life-prolonging alternative therapy was available.

Patient 1 presented with intermediate cytogenetics (47 XX, +8). Cytogenetic remission was achieved with standard 3+7 chemotherapy. In the absence of an optimal donor, the patient was consolidated with 4 courses of high dose cytarabine. Following a disease-free interval of 8 months, the patient relapsed following presentation with thrombocytopenia. Karyotyping at this time confirmed the same diagnostic abnormalities, and mutational analysis further found a FLT3 mutation (ITD). Despite several attempts to induce a second remission (mitoxantrone/etoposide x 1, clofarabine/cytarabine x 1, decitibine/sorafenib x 2) the patient continued to have refractory disease. At this point the patient was treated with an investigational approach (NCT02273102) but progressed rapidly before completing the first cycle of therapy. DST-guided therapy was then prescribed and the patient was treated with bortezomib 1.5mg/m2 on days 1, 4, 8 and 11. Prior to treatment her WBC was 23.8×109/L with 96% circulating blasts. After just 3 doses of bortezomib her WBC normalized and peripheral blasts were no longer detectable. Unfortunately, infectious complications precluded further therapy and the patient ultimately succumbed to the disease.

Patient 3 presented with monosomy 7 AML and no other detectable mutations at diagnosis. The patient had primary refractory disease to cytarabine/daunorubicin x 1, high dose cytarabine x 1, and clofarabine/cytarabine x 1. The patient eventually received a morphologic leukemia free state with decitabine, which was followed by allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation but relapsed shortly after transplant with persistent monosomy 7 and new del(5q) and NRAS mutations. The patient was then treated with DST-guided therapy with gemcitabine. While a reduction in peripheral blast count was observed, it did not meet criteria for response, and the patient died shortly thereafter from complications of graft-versus-host-disease.

Patient 4 presented with a normal karyotype and pathogenic mutations in FLT3 (ITD), ASXL1, CEBPα (monoallelic) and WT1. In the context of primary refractory disease(cytarabine/daunorubicin x 1, clofarabine/cytarabine x 1, mitoxantrone/etoposide x 1), this patient was treated with azacitidine 75mg/m2 and belinostat 1000mg/m2 daily for 5 days based on a DST-guided approach. Complete remission (CR) was achieved after a single course of therapy and she remains disease free following consolidation with stem cell transplantation.

Patient 5 presented with proliferative AML (WBC > 400×106/L) and complex cytogenetic abnormalities in the setting of mutant TP53. Following primary induction failure with standard therapy, the patient continued to have refractory disease with 70% marrow blasts despite salvage therapy (fludarabine/cytarabine/idarubicin x 1, cyclophosphamide/etoposide x 1, azacitidine 75mg/m2 × 7 days x 1). At this point, ex vivo testing of the patient’s leukemic cells identified a combination of vincristine and dexamethasone as a potentially effective treatment. With combined therapy, stable disease of the patients rapidly progressive AML was confirmed for 6 weeks before he was switched to treatment with decitabine (19).

Patient 10 presented with AML characterized by 8;21 translocation [AML1-ETO]. The patient achieved remission with standard 3+7 induction chemotherapy and received 3 cycles of high dose cytarabine consolidation, but then relapsed after 6 months of remission. The patient was treated with cladribine/cytarabine/filgrastim/mitoxantrone salvage therapy, but had refectory disease. Molecular analysis showed TET2, RAD21, and ETV6 mutations. DST-screening identified nilotinib as an active candidate agent. The patient was treated with nilotinib 400mg PO twice daily, but had rapid disease progression. The patient went on to receive another re-induction attempt with clofarabine/cytarabine, but this treatment also failed.

For patients assigned to the non-DST-guided therapy arm, compounds were chosen based on a combination of molecular genetic studies and the patient’s clinical situation, including prior therapies, performance status, organ function and AML subtype/disease biology.

Patient 2 was diagnosed with FLT3-ITD AML and received standard induction with 3+7, followed by 2 cycles of high dose cytarabine consolidation. The patient relapsed 18 months later and underwent 2 attempts at re-induction, with fludarabine/cytarabine/filgrastim followed by mitoxantrone/etoposide, both of which failed. The patient was then treated with sorafenib and radiation to the neck due to extramedullary disease involving cervical lymph nodes. The patient was then treated with decitabine, but progressed. Instead of DST-guided therapy, the patient was enrolled in a phase I clinical trial with tranylcypromine and all-trans retinoic acid, progressed 10 weeks later and due to poor performance status rapidly succumbed to the disease.

Patient 6 presented with monosomy 7, DNMT3A, EZH2 and RUNX1 mutations and underwent induction decitabine for 10 days, followed by 3 cycles of decitabine. Repeat bone marrow examination showed persistent AML. The patient was considered for a phase I clinical trial but did not receive any further treatment due to rapid disease progression.

Patient 7 presented with a history of prostate cancer treated with radiation therapy and AML with normal cytogenetics and CEBPA (monoallelic), CSF3R and TET2 mutations. The patient was treated with azacitidine for 4 cycles without response and then transitioned to decitabine, at which points cells were collected for DST-guided therapy and was planned to receive 2 more cycles of decitabine therapy. However, the patient progressed after cycle 3 and died shortly after.

Patient 8 presented with refractory AML evolved from myelofibrosis. Cytogenetics revealed a translocation of chromosome 3 and deletion of 5q, 4q, and 12q, plus monosomy 7 and monosomy 8. The patient was treated with 3+7 induction, followed by high dose cytarabine consolidation, but remained refractory. Treatment with fludarabine/cytarabine/mitoxantrone achieved a complete cytogenetic remission. The patient also received a matched unrelated donor peripheral blood stem cell transplant, maintaining complete remission. The patient relapsed 5 months after transplant with a new TP53 mutation, and was treated with fludarabine/cytarabine/filgrastim/mitoxantrone salvage chemotherapy and donor lymphocyte infusion (DLI). Unfortunately, the patient progressed during treatment and was not a candidate for further therapy.

Patient 11 presented with complex cytogenetics including del(5q), trisomy 8, monosomy 7, deletion of chromosome 17 and a TP53 missense mutation. Induction with 3+7 was performed and achieved remission; followed by one cycle of intermediate dose cytarabine and 10 cycles of azacitidine as maintenance therapy. The patient maintained remission for over 1 year, but ultimately relapsed. At this point the patient was screened for DST-guided therapy. Instead of DST-guided therapy, the patient was enrolled and treated on a phase I clinical trial with BET inhibitor, resulting in toxicity and disease progression during the first cycle and died soon thereafter.

Patient 12 presented with normal cytogenetics and NPM1 and DNMT3A mutations. Induction with 3+7 was performed and achieved complete remission. This treatment was followed by 3 cycles of high dose cytarabine consolidation. The patient relapsed 4 months after achieving first remission and was treated with mitoxantrone/etoposide salvage chemotherapy, but the treatment failed. At this point, DST screening identified nilotinib as a potential candidate agent. Repeat molecular studies also identified KIT, SETBP1, and TET2 mutations, and 3 new trisomies including +8, in addition to pre-existing NPM1 and DNMT3A mutations. Given the proliferative nature of the disease, the treating physician elected to treat the patient on a phase I clinical trial with cytarabine and OXi4503 but the patient progressed on the clinical trial, at which point a FLT3-ITD mutation had also emerged. The patient is currently treated with azacitidine/sorafenib.

DISCUSSION

AML treatment largely relies on the use of aggressive chemotherapy aimed to induce cancer remission. While this treatment approach is moderately successful in patients under 60 years of age, older patients rarely qualify for standard therapy due to low overall health or reduced tolerance of chemotherapy-induced side effects. Even patients that qualify for the standard 3+7 chemotherapy (anthracycline and cytarabine) and show initial treatment response often require multiple rounds of consolidation chemotherapy, quickly relapse, and succumb to the disease.

Precision medicine approaches are believed to overcome this issue by providing patient-specific treatment recommendations and thus eliminating the need for multiple rounds of different chemotherapeutics. Previous studies, however, have failed to provide evidence of clinical utility (16, 17, 20–23). This is, at least in part, due to long turn over times, that significantly delay patient treatment, and the sole use of sequencing approaches that fail to recognize the importance of epigenetic, proteomic, and other biochemical processes that provide direct insight into treatment response. In addition, the ex vivo measures of treatment responses were often non-selective, difficult to interpret, and challenging to translate into clinical practice.

Here we report the use of an ex vivo drug sensitivity screening platform that can be used to assign patient-specific treatment options without delaying patient treatment in a pilot cohort of 12 patients with refractory AML. In order to test the utility of this screen, all patients were tested using the drug sensitivity screen and then treated based on either DST-guided or non-DST-guided therapy. Patients showed vastly different responses to the 215 FDA-approved compounds used in the screen. Indeed, no compound showed activity in all of the patients, but more than half of the evaluated compounds were not active in any of the patients. The ex vivo drug sensitivity screen recommended compounds not routinely used in AML patients, such as gemcitabine, suggesting that especially heavily pretreated patients would benefit from this approach. No patient was suggested a treatment that they had clinically failed previously, demonstrating the specificity of the approach.

In addition to identifying useful tailored approaches, this strategy also allowed us to identify compounds that increased the proliferative potential of AML blasts, suggesting that certain agents should be used with caution (or avoided completely) in the clinic.

To allow the clinical implementation of the ex vivo drug sensitivity testing, we implemented a workflow that allows for a treatment start 10days after the bone marrow biopsy. This timeline is comparable to standard treatment planning in the non-DST-guided therapy of AML patients. In this small pilot cohort, patients treated with DST-guided therapy showed significantly higher responses when compared to patients treated with non-DST-guided therapy. However, these results may be influenced by the age difference observed between patients treated with DST-guided (mean age =37) vs non-DST-guided (mean age 65) therapy. Although this small population cannot be used to make conclusions on the clinical utility of this method, these suggestive initial results warrant the implementation of a larger clinical trial that will further evaluate whether DST-guided therapy can be used to increase survival in patients with refractory AML.

While the patient specific protein network map projections provide valuable insight into the dysregulation of signaling pathways that influence treatment response, the projections were not used to make treatment decisions in this study because of long turn over times that would delay the treatment start. Further adaptation and streamlining of the workflow will be necessary to include protein network map projections in the clinical decision making process alongside the drug sensitivity screens.

We believe that the combination of ex vivo drug sensitivity testing and patient specific protein network map projections have the potential to significantly improve the survival of patients with refractory AML. Further clinical studies will be needed to streamline the process for clinical use and to evaluate the clinical benefit of this precision medicine approach.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Personalized drug treatment recommendations for refractory AML

Ex vivo drug sensitivity screens assessed individual treatment responses

Guided treatments resulted in significantly higher response rates

Acknowledgments

RS received support from the Miami Clinical and Translational Science Institute, from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (1KL2TR000461), the Paps Corps Champions for Cancer Research and the National Institutes of Health (R21CA202488). JT received research support from the Broward Community Foundation (Fort Lauderdale, FL) and the Pap Corps Champions for Cancer Research (Deerfield Beach, FL). SB received support from the National Institutes of Health (R01NS092671 and R01MH110441). CW’s laboratory is currently publically funded by NIH grants DA035592, DA035055 and AA023781, and Florida Department of Health grants 6AZ08 and 7AZ26. CRC is a Scholar in Clinical Research, Leukemia & Lymphoma Society.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest:

TA is employed by Cellworks Group, Inc. (San Jose, CA).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Cattaneo D, Alffenaar J-W, Neely M. Drug monitoring and individual dose optimization of antimicrobial drugs: oxazolidinones. Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology. 2016;12(5) doi: 10.1517/17425255.2016.1166204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perez F, El Chakhtoura NG, Papp-Wallace K, Wilson BM, Bonomo RA. Treatment Options for Infections Caused by Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: Can We Apply “Precision Medicine” to Antimicrobial Chemotherapy? Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy. 2016;17(6):761–781. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2016.1145658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanguinetti M, Posteraro B. New approaches for antifungal susceptibility testing. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2017.03.025. S1198-743X(17)30195-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeong E, Moon SU, Song M, Yoon S. Transcriptome modeling and phenotypic assays for cancer precision medicine. Arch Pharm Res. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s12272-017-0940-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muraro MG, Muenst S, Mele V, Quagliata L, Iezzi G, Tzankov A, Weber WP, Spagnoli GC1, Soysal SD13. Ex-vivo assessment of drug response on breast cancer primary tissue with preserved microenvironments. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6(7):e1331798. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1331798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meijer TG, Naipal KA, Jager A, van Gent DC. Ex vivo tumor culture systems for functional drug testing and therapy response prediction. Future Sci OA. 2017;3(2):FSO190. doi: 10.4155/fsoa-2017-0003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yadav B, Pemovska T, Szwajda A, Kulesskiy E, Kontro M, Karjalainen R, Majumder MM, Malani D, Murumägi A, Knowles J, Porkka K, Heckman C, Kallioniemi O, Wennerberg K, Aittokallio T. Quantitative scoring of differential drug sensitivity for individually optimized anticancer therapies. Sci Rep. 2014;4:5193. doi: 10.1038/srep05193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pemovska T, Kontro M, Yadav B, Edgren H, Eldfors S, Szwajda A, Almusa H, Bespalov MM, Ellonen P, Elonen E, Gjertsen BT, Karjalainen R, Kulesskiy E, Lagström S, Lehto A, Lepistö M, Lundán T, Majumder MM, Marti JM, Mattila P, Murumägi A, Mustjoki S, Palva A, Parsons A, Pirttinen T, Rämet ME, Suvela M, Turunen L, Västrik I, Wolf M, Knowles J, Aittokallio T, Heckman CA, Porkka K, Kallioniemi O, Wennerberg K. Individualized systems medicine strategy to tailor treatments for patients with chemorefractory acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Discov. 2013;3(12):1416–29. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bosanquet AG, Bell PB. Ex vivo therapeutic index by drug sensitivity assay using fresh human normal and tumor cells. J Exp Ther Oncol. 2004;4(2):145–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brigulová K, Cervinka M, Tošner J, Sedláková I. Chemoresistance testing of human ovarian cancer cells and its in vitro model. Toxicol In Vitro. 2010;24(8):2108–15. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ehemann V, Kern MA, Breinig M, Schnabel PA, Gunawan B, Schulten HJ, Schlaeger C, Radlwimmer B, Steger CM, Dienemann H, Lichter P, Schirmacher P, Rieker RJ. Establishment, characterization and drug sensitivity testing in primary cultures of human thymoma and thymic carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2008;122(12):2719–25. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurtz SE, Eide CA, Kaempf A, Khanna V, Savage SL, Rofelty A, English I, Ho H, Pandya R, Bolosky WJ, Poon H, Deininger MW, Collins R, Swords RT, Watts J, Pollyea DA, Medeiros BC, Traer E, Tognon CE, Mori M, Druker BJ, Tyner JW. Molecularly targeted drug combinations demonstrate selective effectiveness for myeloid- and lymphoid-derived hematologic malignancies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017:201703094. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1703094114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Cancer Society’s Cancer Statistics Center

- 14.Cancer Genome Atlas Research, N. Genomic and epigenomic landscapes of adult de novo acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(22):2059–74. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Welch JS, Ley TJ, Link DC, Miller CA, Larson DE, Koboldt DC, Wartman LD, Lamprecht TL, Liu F, Xia J, Kandoth C, Fulton RS, McLellan MD, Dooling DJ, Wallis JW, Chen K, Harris CC, Schmidt HK, Kalicki-Veizer JM, Lu C, Zhang Q, Lin L, O’Laughlin MD, McMichael JF, Delehaunty KD, Fulton LA, Magrini VJ, McGrath SD, Demeter RT, Vickery TL, Hundal J, Cook LL, Swift GW, Reed JP, Alldredge PA, Wylie TN, Walker JR, Watson MA, Heath SE, Shannon WD, Varghese N, Nagarajan R, Payton JE, Baty JD, Kulkarni S, Klco JM, Tomasson MH, Westervelt P, Walter MJ, Graubert TA, DiPersio JF, Ding L, Mardis ER, Wilson RK. The origin and evolution of mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. Cell. 2012;150(2):264–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dohner H, Gaidzik VI. Impact of genetic features on treatment decisions in AML. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2011;2011:36–42. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2011.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith FO. Personalized medicine for AML? Blood. 2010;116(15):2622–3. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-296418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kortlepel K, Bendall LJ, Gottlieb DJ. Human acute myeloid leukemia cells express adhesion proteins and bind to bone marrow fibroblast monolayers and extracellular matrix proteins. Leukemia. 1993;7:1174–1179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Welch JS, Petti AA, Miller CA, Fronick CC, O’Laughlin M, Fulton RS, Wilson RK, Baty JD, Duncavage EJ, Tandon B, Lee YS, Wartman LD, Uy GL, Ghobadi A, Tomasson MH, Pusic I, Romee R, Fehniger TA, Stockerl-Goldstein KE, Vij R, Oh ST, Abboud CN, Cashen AF, Schroeder MA, Jacoby MA, Heath SE, Luber K, Janke MR, Hantel A, Khan N, Sukhanova MJ, Knoebel RW, Stock W, Graubert TA, Walter MJ, Westervelt P, Link DC, DiPersio JF, Ley TJ. TP53 and Decitabine in Acute Myeloid Leukemia and Myelodysplastic Syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(21):2023–2036. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1605949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Villman K, Blomqvist C, Larsson R, Nygren P. Predictive value of in vitro assessment of cytotoxic drug activity in advanced breast cancer. Anticancer Drugs. 2005;16(6):609–15. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200507000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamada S, Hongo T, Okada S, Watanabe C, Fujii Y, Ohzeki T. Clinical relevance of in vitro chemoresistance in childhood acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2001;15(12):1892–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.