Abstract

The A3 adenosine receptor (A3AR) subtype is a novel, promising therapeutic target for inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and psoriasis, as well as liver cancer. A3AR is coupled to inhibition of adenylyl cyclase and regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways, leading to modulation of transcription. Furthermore, A3AR affects functions of almost all immune cells and the proliferation of cancer cells. Numerous A3AR agonists, partial agonists, antagonists, and allosteric modulators have been reported, and their structure–activity relationships (SARs) have been studied culminating in the development of potent and selective molecules with drug-like characteristics. The efficacy of nucleoside agonists may be suppressed to produce antagonists, by structural modification of the ribose moiety. Diverse classes of heterocycles have been discovered as selective A3AR blockers, although with large species differences. Thus, as a result of intense basic research efforts, the outlook for development of A3AR modulators for human therapeutics is encouraging. Two prototypical selective agonists, N6-(3-Iodobenzyl)adenosine-5′-N-methyluronamide (IB-MECA; CF101) and 2-chloro-N6-(3-iodobenzyl)-adenosine-5′-N-methyluronamide (Cl-IB-MECA; CF102), have progressed to advanced clinical trials. They were found safe and well tolerated in all preclinical and human clinical studies and showed promising results, particularly in psoriasis and RA, where the A3AR is both a promising therapeutic target and a biologically predictive marker, suggesting a personalized medicine approach. Targeting the A3AR may pave the way for safe and efficacious treatments for patient populations affected by inflammatory diseases, cancer, and other conditions.

Keywords: A3 adenosine receptor, inflammation, cancer, drug development, therapy

1 INTRODUCTION

The relevance of adenosine in the immune system has been established based on mounting scientific evidence showing that the nucleoside represents a paracrine inhibitor of inflammation, regulating the onset, extension, and termination of the inflammatory process and acting through four G protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), designated as A1, A2A, A2B, and A3 adenosine receptors (ARs).1 Following inflammation, metabolic alterations occur leading to an increase of extracellular adenosine that is present in the low nanomolar range under physiological conditions, while in stressful conditions it can rise to micromolar levels.2 Adenosine in the extracellular milieu is largely formed by hydrolysis/dephosphorylation of ATP, ADP, and AMP through specific ectonucleotidases termed ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase (CD39) and ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73).3,4 Intracellular levels of adenosine are derived from hydrolysis of AMP and S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH) through cytosolic 5′-nucleotidase, and SAH hydrolase, respectively. Adenosine activity is extinguished through its phosphorylation to AMP by adenosine kinase (AK) or deamination to inosine by adenosine deaminases (ADA1 and ADA2), with ADA present also extracellularly.2 The existence of concentrative nucleoside transporters (CNTs) and equilibrative nucleoside transporters (ENTs) regulates the extra- and intracellular adenosine concentrations.5

The A3AR, the last of the four subtypes to be discovered, was cloned sequentially in rat, sheep, and human,6–8 but it was not shown to respond as an AR from the outset. One of the first activities of this receptor to be reported was the induction of histamine from rat basophilic cells.9 The discovery and initial characterization of the A3AR, and the exploration of its biological paradoxes, has led to the synthesis and biological characterization of a multitude of receptor probe molecules and clinically relevant candidate molecules, including orthosteric agonists and antagonists as well as allosteric enhancers. This discovery of the A3AR as a fourth AR has spawned current and projected clinical trials of several A3AR agonists and potentially of a selective A3AR allosteric enhancer, as well.10

Using mechanisms triggered by adenosine to inhibit the immune system is a very exciting area of research, and increasing attention is focused on their elucidation in the context of developing new anti-inflammatory strategies. Thus, today the A3ARsubtype is considered a novel, very promising therapeutic target and predictive biological marker, given its overexpression in inflammatory and cancer cells, compared to low levels found in healthy cells.11

The aim of this review is to summarize the state and the progress of the field of A3AR modulators and their clinical development in the context of inflammation and cancer and other conditions, with an emphasis on rheumatoid arthritis (RA), psoriasis, and hepatocellular carcinoma.

2 MOLECULAR BIOLOGY OF A3AR

The A3AR, the only AR subtype cloned before its pharmacological identification, was initially isolated from rat testis and then from a variety of species. The A3AR structure had a sequence homology of only 74% in rat versus sheep and human, versus 85% between sheep and human, suggesting significant interspecies differences in ligand recognition. This is manifested in different pharmacological profiles of the species homologs, especially with respect to antagonist binding, which have made the characterization of this AR subtype difficult.12 There are also species differences in the biological roles of the A3AR, for example, as the main mechanism for adenosine–induced release of inflammatory mediators in rat mast cells, but not in those of human.13

The A3ARis located on human chromosome 1p21-p13 and consists of a single chain of 318 amino acids.14 The A3AR gene presents two exons separated by a single intron of about 2.2 kb.15 Its promoter region has putative binding sites for multiple transcription factors: The upstream sequence has a CCAAT sequence, as well as consensus binding sites for SP1, NF-IL6, GATA1, and GATA3 transcription factors, the latter of which is important for the A3AR-dependent role in immune function. Two species of mRNA code for the hA3AR (sizes 2 and ~5 kb). Variants of the A3AR have been shown to be associated with coronary heart disease, autism spectrum disorder, and aspirin-induced urticaria.16–18 Recently, the A3AR 3′-UTR (untranslated region) of the mRNA was found to be targeted by the proinflammatory microRNA (miR-206) in ulcerative colitis leading to downregulation of A3AR mRNA/protein expression in colon cells.19 The A3AR is expressed in diverse tissues at relatively low levels, compared to A1AR and A2AAR. Genomic analysis of the expression of the A3AR gene in various human tissues (Table 1A) shows highest levels in testes, the spinal cord, and various brain regions, bladder, lung, adipose tissue, and whole blood. The highest expression reached 12.4 RPKM (reads per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads), while comparable data for A1AR and A2AAR and exceeded 20 RPKM at maximal levels in specific tissues. This suggests that potential use of A3AR ligands in pain and other nervous system disorders is supported by the presence of the receptor in these tissues, although the cell type is not determined in this RNA sequencing data. Various cancer tumors also show major alteration in A3AR expression in comparison to normal tissue. As accessed from a public cancer database (Table 1B), in 393 unique genomic analyses of cancerous tumors, 25 showed a significant increase in A3AR (P < 10−4) and 28 showed a significant decrease compared to normal tissue of the same type. The most prominent increases were in brain cancer (particularly glioblastoma and astrocytoma) and kidney cancer (particularly renal clear cell carcinoma). Thus, the approach of using of A3AR ligands in a wide range of cancers coincides with significant changes in the receptor expression level in tumors.

TABLE 1.

Expression of the A3AR RNA in Normal and Cancerous Tissues from Public Databases

| (A) Exon expression for the A3AR gene in various postmortem human tissues, from RNA sequencing dataa,b | |

|---|---|

| Tissue | RPKMb |

| Testes | 12.401 |

| Brain (spinal cord, cervical C-1) | 5.612 |

| Brain (substantia nigra) | 4.268 |

| Adrenal gland | 3.884 |

| Spleen | 3.495 |

| Small intestine (terminal ileum) | 2.778 |

| Brain (amygdala) | 2.405 |

| Brain (hypothalamus) | 2.201 |

| Nerve (tibial) | 2.102 |

| Brain (hippocampus) | 1.99 |

| Bladder | 1.764 |

| Lung | 1.747 |

| Adipose (subcutaneous) | 1.73 |

| Whole blood | 1.709 |

| Colon (transverse) | 1.604 |

| Artery (coronary) | 1.517 |

| (B) Alteration in the level of A3AR in cancerous tumors compared to normal tissuec | |

| Tumor | Percentile (no. of analyses)c |

| Upregulation | |

| Brain and CNS cancerd | 1% (4/29) |

| Kidney cancer | 1% (6/20) |

| Breast cancer | 5% (11/43) |

| Esophageal cancer | 10% (1/9) |

| Downregulation | |

| Bladder cancer | 5% (3/10) |

| Colorectal cancer | 5% (12/33) |

| Sarcoma | 5% (1/31) |

| Brain and CNS cancer | 10% (1/29) |

| Cervical cancer | 10% (1/10) |

| Myeloma | 10% (1/8) |

Data from The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) Project. The data were accessed from the GTEx portal (http://www.gtexportal.org/home/) on February 9, 2017, GTEx Analysis Release V6p (dbGaP Accession phs000424.v6.p1).

RPKM stands for reads per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads for the A3AR gene (ADORA3, gencode ID ENSG00000121933.13). The highest 16 values are shown from a total of 53 tissues assayed.

Percentile refers to the best gene rank percentile for the analyses within the cell. The data were accessed from http://oncomine.org on February 9, 2017, using gene summary visualization for ADORA3. Ratio refers to the number of analyses out of the total number that met the criterion of p < 10−4 for the change in expression in cancer versus normal tissue.

Highly significant upregulation of ADORA3 noted in numerous analyses of glioblastoma and astrocytoma.

As is common to the GPCR superfamily, the A3AR is characterized by seven transmembrane (TM) domains and an intracellular C-terminal region, with Ser and Thr residues serving as potential phosphorylation sites relevant for rapid receptor desensitization. Following agonist stimulation, the A3AR undergoes phosphorylation at the C-terminus by GPCR kinases and subsequent internalization through clathrin-coated pits.20–24 Interestingly, by mutational studies, it has been reported that the highly conserved Trp (W6.48) in TM6 is essential for the active conformation of A3AR necessary to trigger a series of intracellular pathways for signal transmission, to interact with β-arrestin2, and to undergo receptor internalization.25 Furthermore, use of a novel fluorescent A3AR agonist has allowed for the observation of colocalization with internalized receptor–arrestin complexes.26

The energetics of A3AR ligand interactions has been studied using a thermodynamic approach. The thermodynamic parameters of ligand binding at all ARs are similar within either agonist or antagonist classes, which reflects a common ligand receptor interaction mechanism with other ARs This commonality is proposed to explain the difficulty in designing selective adenosine ligands.27–29

3 DISTRIBUTION IN IMMUNE AND CANCER CELLS

The A3AR is highly expressed in several immune cell types, as well as in cancer cells.11 In particular, the native human A3AR was first revealed in human eosinophils and subsequently in neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages, foam cells, dendritic cells, lymphocytes, splenocytes, bone marrow cells, lymphonodes, synoviocytes, chondrocytes, osteoblasts, and mast cells.9,13,30–63 Overall, the presence of the A3ARin almost all the cells involved in inflammatory processes suggests their potential involvement in a number of inflammatory pathologies, spanning from wound healing and remodeling to lung injury, inflammatory bone loss, autoimmune, and eye diseases.2 In addition, high A3AR expression has been observed using biochemical methods in many of types of cancer cells, including astrocytoma, melanoma, lymphoma, sarcoma, glioblastoma, colon, liver, pancreas, prostate, thyroid, lung, breast, and renal carcinomas.64–89 This expression pattern reflects a demonstrated role for this subtype in tumor biology.

4 MEDICINAL CHEMISTRY OF THE A3 ADENOSINE RECEPTOR

4.1 Adenosine derivatives as agonists of the A3 adenosine receptor

The first efforts to develop A3AR selective agonists (Table 2) were performed at the US National Institutes of Health (NIH),90 and culminated in the report of N6-(3-iodobenzyl)adenosine-5′-N-methyluronamide (IB-MECA 1, Fig. 1), which is ~50-fold selective for the A3AR in rat compared to the A1AR and A2AAR.91,92 The first few years of medicinal chemical optimization of the affinity and selectivity of A3AR agonists relied entirely on comparison of binding affinities at the rat ARs,56 because the human homologues were not available initially.7 A successful approach was to combine multiple A3AR enhancing substitutions in adenosine analogues. Thus, IB-MECA contained a substituent that enhanced affinity at the ARs including A3AR, for example, a 5′-N-alkyluronamide, with an N6-benzyl substituent that maintained affinity at this subtype but reduced affinity at the A1AR and A2AAR. Initially, an unsubstituted N6-benzyl group served this purpose, and later a halo atom at the 3-position of the benzyl ring was shown to increase A3AR affinity and selectivity.92 Optimization of the 5′-N-alkyluronamide demonstrated that methyl was more favorable for A3AR binding than larger alkyl groups. A combination with 4-amino-3-iodo substitution of the N6-benzyl group maintained high affinity, but not high selectivity at the A3AR; thus, compound 3 became a widely used high-affinity radioligand in cells and membranes highly expressing this receptor.56 A 3-isothiocyanatobenzyl group was also tolerated at the N6-position, which provided the first selective chemically reactive affinity label of the rat A3AR, termed ICBM(N6-(3-isothiocyanatobenzyl)-5.-N-methylcarboxamidoadenosine) 4.93 In a subsequent study of the structure–activity relationship (SAR), a third position of derivatization was explored: the C2-position.94 It was noted that 2-[p-(2-carboxyethyl)phenyl-ethylamino]-5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (CGS21680 1695), originally introduced as an A2AAR-selective agonist, surprisingly displayed affinities (nanomolar, all human homologues) in the order A2AAR (27) > A3AR (67) > A1AR (289).149 Based on this initial observation, it was apparent that the A3AR binding site was flexible in the ability to accommodate a variety of C2 substituents, including sterically bulky groups. Thus, the order of potency of CGS21680 was A2AAR > A3AR > A1AR ≫ A2BAR. Nevertheless, the 2-chloro analogue 2 of IB-MECA was the focus at that time as an A3AR agonist of increased selectivity, since other C2 modifications were not yet systematically explored. Later, an extended C2-alkynyl group, initially in the form of 6-hexynyl, was shown to be tolerated in adenosine derivatives in binding to the A3AR.96,97 This modification was also compatible with a 5′-N-ethyluronamide group, an observation that led to the identification of HE-NECA 7 as a potent, but nonselective A3AR agonist.98,99

TABLE 2.

Affinity of Selected Nucleoside Derivatives in Binding at Human ARs

| Compound | pKi value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| A1AR | A2AAR | A3AR | ||

| Agonists | ||||

| 1120 | IB-MECA | 7.29 | 5.50 | 8.74 |

| 2120 | Cl-IB-MECA | 6.66 | 5.27 | 8.85 |

| 799,103 | HE-NECA | 7.22 | 8.19 | 8.62 |

| 899,103 | PE-NECA | 6.25 | 6.21 | 8.21 |

| 999,103 | PHP-NECA (R,S) | 8.57 | 8.51 | 9.38 |

| 1099,103 | PEMADO | 4.48 | 4.38 | 8.52 |

| 11104 | 4.27 | 4.98 | 8.60 | |

| 13110 | CP-608,039 | 5.14 | <4.3 | 8.24 |

| 14a126 | <5 | <5 | 7.81 | |

| 14b126 | 6.71 | 5.36 | 9.42 | |

| 15a132 | LC257 | 5.79 | <4 | 8.74 |

| 15b132 | 5.42 | <5.30 | 8.70 | |

| 1695 | CGS21680 | 6.54 | 7.57 | 7.17 |

| 20105 | MRS3558 | 6.59 | 5.64 | 9.54 |

| 21119 | MRS5151 | 4.83 | ~5 | 8.62 |

| 22117 | MRS3630 | 7.74 | 5.49 | 8.43 |

| 25120,121 | MRS5698 | <5 | <5 | 8.52 |

| 26121 | MRS5679 | <5 | <5 | 8.51 |

| 27121 | MRS5980 | <5 | <5 | 9.15 |

| 29122 | MRS5841 | <5 | <5 | 8.72 |

| 32134 | MRS5919 | <5 | <5 | 8.22 |

| Antagonists and partial agonists | ||||

| 33136,142 | <4 | <4 | 6.19 | |

| 35128 | MRS1292 | ND | ND | 7.53a |

| 37109 | 5.80 | 5.32 | 7.91 | |

| 39139 | 5.60 | 6.47 | 8.38 | |

| 41143 | <4 | 8.14 | 7.93 | |

| 42175 | MRS3771 | 5.23 | <5 | 7.54 |

| 45125 | MRS5776 | <5 | <5 | 7.70 |

| 46140 | <5 | 5.13 | 8.31 | |

| 47141 | 9.36 | 7.11 | 8.52 | |

pKi at rat A3AR = 7.31.

ND, not determined.

FIGURE 1.

Structures of adenosine or 1,3-dialkylxanthine riboside derivatives that act as agonists of the A3AR. Compound 16 (CGS21680, not shown) is an A2AAR agonist

Unlike the C2-position, modification of the 2′ and 3′ hydroxyl groups was highly detrimental to A3ARbinding affinity of simple adenosine analogues,96 but a 3′-deoxy analogue of 2 (structure not shown) was later found to be a selective, full agonist at the rat A3AR with a binding Ki value of 33 nM.100 The ribose 5′-position was also amenable to modification beyond 4′-CH2OH and 5′-N-alkyluronamides. For example, 5′-methyl ether analogue NNC53-0055 6 was an agonist at the A3AR,101 and 5′-alkylthioethers were tolerated at the A3AR.102 Acylation of the N6-NH reduced affinity at the A3AR in comparison to the mono-alkylated analogues.97 The flexibility of substitution at the N6-position compatible with A3AR affinity was higher than initially indicated in the report on 1. For example, small alkyl and alkoxy groups, such as N6-methyl in 10 and N6-methyloxy in 6 and 11, could be appended to the nitrogen.99,101–104 However, a small alkyl group at the N6-position often reduced affinity at the rat A3AR compared to the human homologue. The human A3AR tolerated larger N6 substituents, such as the preferred 1S,2R stereoisomer of N6-cyclopropylphenyl in 17.105 The adenine moiety could be replaced with other heterocyclic nucleobases, leading to the retention of A3AR affinity and selectivity, but only in limited cases. For example, xanthine-7-ribosides such as DBXRM 5 were shown to fully activate the A3AR by virtue of an intact 5′-N-methyluronamide.106 Recently, in silico screening using an A2AAR crystal structure identified alternative nucleobases that, when ribosylated, retained receptor affinity and efficacy at the A3AR and other ARs. 107 Various pyridine-3,5-dicarbonitrile derivatives also bind to and activate ARs as atypical agonists, but they are not selective for the A3AR.108

The prototypical A3AR selective agonists 1 (CF101, Piclidenoson) and 2-chloro-N6-(3-iodobenzyl)-adenosine-5′-N-methyluronamide (Cl-IB-MECA 2, CF102, Namodenoson) are both in clinical trials for inflammation and cancer, respectively.10 They have demonstrated safety and clinical efficacy in Phases I and II trials. IB-MECA is now about to enter larger Phase III trials for RA and psoriasis, while Cl-IB-MECA is now about to enter a Phase II trial for primary liver cancer. 1 and 2 have also become widely used pharmacological probes with 2 being more selective for the rat and human A3AR. However, at the mouse A3AR, an exceptionally high affinity with Ki value of 87 pM was noted for 1, leading to 69-fold and >10,000-fold selectivity in comparison to mouse A1AR and A2AAR, respectively.109 Two other agonists of the A3AR, 12 and 13, were considered for clinical application to anti-ischemic cardioprotection.110 Compound 13 was unusually water soluble due to the presence of a 3′-amino group, which is largely protonated in physiological medium. Another highly selective A3AR agonist 15b containing a C2-pyrazolyl group was reported.111

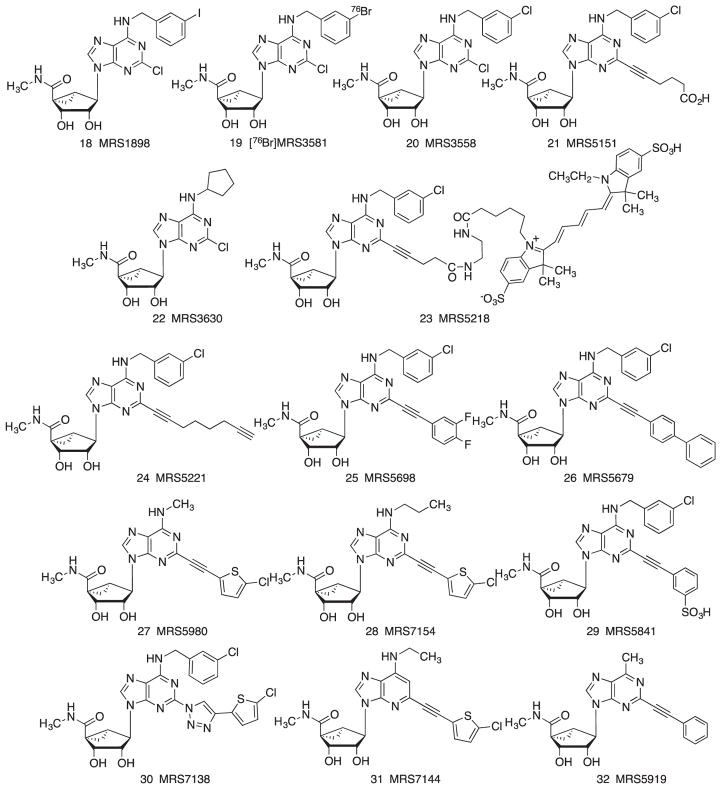

In 2000, Jacobson et al. reported that conformationally constraining a ribose-like moiety in the form of bicyclic ring increased the A3AR selectivity.112 The methanocarba group, that is, a bicyclo[3.1.0]hexane in place of the tetrahydrofuryl group of native ribose, had been applied earlier to antiviral drugs,113 and this was the first report of its incorporation in signaling ligands. Two isomeric forms of the methanocarba ring system, depending on the fusion point of the cyclopropane and cyclopentane rings, enforce either a North (N) (Fig. 2) or South (S) envelope conformation of the pseudoribose. A priori, the conformational preference of the ARs in binding ribose was not known, but the (N) isomer of simple adenosine was found to have >100-times the affinity of the corresponding (S) isomer at the A3AR. Thus, this derivatization approach of using chemically constrained rings can be used to probe the conformational preference of a given receptor. Among the four ARs, the greatest affinity gain with the (N)-methanocarba ring occurred at the A3AR. Numerous A3AR selective agonists were subsequently reported that included this major modification that enhanced affinity and selectivity at the A3AR compared to other ARs. The (N)-methanocarba modification is compatible with many other A3AR affinity-enhancing groups, such as 5′-N-alkyluronamides and N6-benzyl groups.114 Incorporation of the (N)-methanocarba modification in IB-MECA 1 resulted in MRS1898 18, a potent and moderately selective A3AR agonist that was later radiolabeled to provide a selective radioligand for the rodent A3AR.115 Other halogens could be placed at the 3-position, such as bromo 19 and chloro 20; the 3-bromo equivalent 19 provided a selective A3AR agonist as a 76Br-labeled positron emitter for receptor imaging studies.116

FIGURE 2.

Structures of (N)-methanocarba-adenosine derivatives that act as agonists of the A3AR

The A3AR-favoring (N)-methanocarba-5′-N-methyluronamide scaffold could also be combined with an A1AR-favoring substituent (N6-cyclopentyl) to provide a dual acting A1/A3AR agonist 22 that displayed cardioproprotective properties, as both receptors demonstrate anti-ischemic properties in heart.117

The C2-position could also be derivatized with (aryl)alkylthio groups, which resulted in moderate A3AR affinity but not selectivity.118 The C2-position substitution was expanded to include alkynyl and arylalkynyl groups that were compatible with both the riboside and (N)-methanocarba series.97,103,104 C2-ethynyl and arylethynyl groups were shown to further increase A3AR selectivity of adenosine analogues, that is, ribosides 7–11 and (N)-methanocarba derivatives such as 23–29.119–123 A carboxylic acid congener 21 is an A3AR agonist that displayed greater water solubility and the option of conjugation without losing receptor affinity. A lower homologue of 21 was used as a carboxy-bearing pharmacophore to condense with an amine-functionalized Cy5 fluorophore in the fluorescent A3AR-selective agonist MRS5218 23 of high A3AR affinity. 23 is selective for the A3AR in human and mouse and is suitable for characterization of the receptor in live cells using flow cytometry.124 Compound 24 contains a terminal alkyne group, as well as an alkyne at the C2 fusion position, and is suitable for click coupling to carriers such as gold nanoparticles with the retention of A3AR affinity and selectivity. A 3,4-difluorophenyl ethynyl group in 25 was particularly conducive to attaining high A3AR affinity in multiple species. Thus, the Ki value of 25 was approximately 3 nM at both the human and mouse A3ARs. The tolerance of the receptor for extended C2 substituents was surprising—even a biphenyl substituent in 26 preserved high A3AR affinity, which was explained based on conformational plasticity of TM2.120,125 A3AR-selective agonist 29 contains a sulfonate group that renders it unable to diffuse through biological barriers such as the blood–brain barrier. Thus, it is useful in vivo for distinguishing peripheral and central A3AR effects.122 The preferred placement of a sulfonate group on the scaffold of C2-arylethynyl-methanocarba-adenosine-5′-N-methyluronamides was predicted successfully using computational modeling of the receptor interactions at the human and mouse A3ARs.

In 2003, the group of Lak Shin Jeong in South Korea synthesized thionucleoside analogues that were shown to be highly potent and selective as A3AR agonists.126 The SAR upon modification of thionucleosides at the C2, N6 and 5′-positions was explored in detail. The 4′-thio modification of adenosine analogues was found to be compatible with many other A3AR affinity-enhancing groups, such as 5′-N-alkyluronamides and a range of N6 substitutions. Compounds 14a and 14b are analogues of IB-MECA 1 and Cl-IB-MECA 2, respectively, which were found to be highly potent and selective in A3AR binding. Compound 14b has been shown to suppress angiogenesis, a property that might be beneficial in treating cancer, diabetic retinopathy, and inflammatory diseases.127

To summarize the SAR described, A3AR affinity and selectivity of agonists are based on substitution at the C2, N6, and 5′ positions of adenosine,128 and only limited ribose functional group substitution of nucleosides is tolerated at this receptor. Some potent A3AR agonists such as 13 contain a 3′-amino-3′-deoxy modification of adenosine,110 but this modification does not apply universally. Although highly specific A3AR agonists were obtained in SAR studies, their binding Ki values were not directly predictive of the magnitude of an in vivo protective response, for example, in reducing chronic neuropathic pain. Thus, it became necessary to measure parameters other than simple binding affinities (such as half-life, duration of response, and maximal efficacy in vivo) to select for molecules with translational potential. An in vivo phenotypic screen in real time of the action of A3AR agonists to reduce or prevent chronic neuropathic pain was adopted for a comparison of diverse substitutions at these positions on the adenosine scaffold.121 The data obtained in a mouse model of neuropathic pain, that is, chronic constriction injury (CCI) of Bennett and Xie,129 allowed the chemists to steer the SAR in the direction of compounds that displayed high efficacy in reducing hyperalgesia and a long duration of action in vivo upon oral administration. The CCI model was ideally suited for the comparison of antinociceptive activity of A3AR agonists because of their high potency (greater than the molar potency of other pain medications) and because they lacked activity in tests of acute pain, such as the hot plate test and tail flick assay.130 The efficacy and duration of action of novel A3AR agonists after p.o.per os administration indirectly indicated favorable oral bioavailability and pharmacokinetics, at least with respect to chronic neuropathic pain. Thus, this phenotypic screen proved to be an invaluable guide in the extension of the SAR in this compound series.

This in vivo phenotypic screen confirmed that C2-phenylalkynyl analogues were among the preferred A3AR agonists. The terminal cyclic group in the C2-alkyne series was then varied to include diverse 6-membered rings, 5-membered heterocyclic rings, and cycloalkyl rings.121 With respect to A3AR binding and selectivity, many of these groups, including substituted phenyl rings, maintained high A3AR affinity and selectivity. However, the in vivo phenotypic screen identified 5-membered heterocyclic rings, such as thienyl derivatives, as being particularly potent and efficacious in vivo in the chronic neuropathic pain model. A 5-chlorothienylethynyl group in MRS5980 27 and MRS7154 28 was found to prolong the protective action of A3AR agonists in the CCI model. The substitution of the N1 group of the adenine moiety with CH in 31 was well tolerated in A3AR binding and activation and in the CCI model.

Due to the possibility that the C2-arylethynyl group could serve as a Michael reaction acceptor in nucleophilic attacks, alternative bioisosteric extensions at the C2-position were compared. The aryltriazolyl group in MRS7138 30 was found to mimic the geometry of the corresponding arylethynyl group when the (N)-methanocarba nucleoside was receptor bound,131 and this substituent would not have liability as a potential Michael acceptor. This conformational relationship was predicted using molecular docking to a homology model of the A3AR. C2-triazole substitution (two positional isomers) was previously found to be compatible with A3AR binding in the riboside series, as in 15a and 15b.132 As a postscript to that effort to replace the C2-arylethynyl group, this ethynyl group was found to be relatively unreactive toward thiols such as glutathione, and the risk of such compounds depleting liver glutathione was shown to be very small.133

The surprising finding that substitution of the exocylic NH of adenine with H or CH3 in MRS5919 32 allowed full activation of the A3AR emphasized that the loss of otherwise important recognition elements in a ligand can be compensated by other affinity enhancing moieties on the nucleoside.134 Moreover, the ribose moiety is the main effector of receptor activation, while adenine modifications tend to change the subtype selectivity but usually do not have a major effect on the agonist efficacy. However, there are exceptions to the above generalization, including various N6 substituents and C2 substituents that produce partial agonism or antagonism at the A3AR, as has been summarized,135 and nucleoside derivatives with reduced efficacy are discussed below.

4.2 Nucleoside derivatives as partial agonists and antagonists of the A3 adenosine receptor

Selected nucleoside derivatives that act as antagonists or low efficacy agonists at the A3AR are shown in Figure 3. The truncation of hydroxyl groups of adenosine nucleosides, that were demonstrated to be A3AR-selective agonists, was first explored in 1995.96–99 The goal was to reduce the hydrophilicity of the nucleosides to increase bioavailability without loss of receptor affinity. A secondary goal was to probe the effect on intrinsic efficacy of the truncated nucleosides as A3AR agonists, although it was not immediately achieved.100 The conversion of adenosine agonists into antagonists by complete removal of the ribose ring, that is, in adenine derivatives, was previously demonstrated, but the pharmacological characteristics of intermediate structures, that is, those with partially truncated ribose moieties, were unknown. Among the four ARs, the A3AR appears to be the easiest with respect to conversion of nucleoside agonists into antagonists, and numerous examples have been reported.109,128,132,135–141 However, it should be noted that the degree of efficacy can vary, depending on the functional assay and the receptor expression level. Thus, a modified nucleoside that behaves as an A3AR antagonist in one system, such as binding of a radiolabeled guanine nucleotide, might still activate the receptor under different circumstances, such as measurement of inhibition of adenylate cyclase.115

FIGURE 3.

Structures of (N)-methanocarba and riboside derivatives of adenosine or 1,3-dialkylxanthine that act as partial agonists or antagonists of the A3AR

Cristalli and co-workers took another approach to achieve A3AR antagonism. The presence of 8-alkynyl substituents on adenosine (4′-CH2OH) analogues, such as 33, reduced the ability of the A3AR-selective nucleoside to activate the receptor, as is consistent with antagonism.136,142 The theme of reduced efficacy in truncated nucleosides, rigid nucleosides, and otherwise modified ribosides was developed in pharmacological studies of Gao et al.137 The requirement of an H-bond donating group at the 5′-position of nucleoside analogues for A3AR activation was also demonstrated. A spirolactam 35 related structurally to IB-MECA 1 retained selectivity of binding to the rat and human A3ARs, but completely lacked the ability to activate the receptors and was shown to be a functional antagonist. Thus, a degree of flexibility of the 5′-amide, which is capable of forming multiple H bonds with the receptor, was required for full A3AR activation. Xanthine-7-riboside 34 was a partial agonist at the rat A3AR but an antagonist at the A1AR.106 An N6 substituent that converted A3AR agonist activity into antagonism was the N6-(2,2-diphenyl)ethyl group in 36.105 Curiously, the corresponding rigidified N6-fluorenylmethyl analogue (structure not shown), upon addition to an aryl-aryl bind to 36, became a full agonist. The combination of a N6-benzyl-type substituent with 2-chloro in 38 reduced the efficacy at the A3AR to nearly zero, although its residual efficacy could be expanded to full efficacy in the presence of A3AR PAM LUF6000 95 (where PAM is positive allosteric modulator).108 Modification at the 5′-position as an ester 37 produced a low-efficacy partial agonist, while 5′-N,N-dialkyluronamide in 42 resulted in antagonism at the A3AR.109 Thus, conformational factors at various regions surrounding the adenosine core and H-bonding around the 5′-position are determinants of A3AR efficacy.128

The 4′-truncation of the A3AR nucleosides was explored in great detail for the 4′-thionucleosides 138,139 leading to compounds 39 and 40, which were shown to be antagonists using a functional assay of guanine nucleotide binding. However, the 2-hexynyl group of compound 41 added a second activity to this series of A3AR ligands, that is, 41 was a combined potent A3AR antagonist and A2AAR agonist.143 Truncation of the nucleoside ribose-like moiety in the (N)-methanocarba series also led to A3AR-selective antagonists and partial agonists,109 including a radiolabeled 3-bromo analogue 44 for positron emission tomography (PET).116 Compound 45 is a selective antagonist of both the human and mouse A3ARs.120,125 Compound 46 is a selective A3AR antagonist with renal protective properties.139 Compound 47 is a mixed A1/A3AR antagonist that also displays functional agonism at the A2AAR, which displayed greater potency than predicted from its only moderate affinity in A2AAR binding assays.141

4.3 Non-nucleoside derivatives as antagonists of the A3 adenosine receptor

For more than 20 years, the advance of potent and selective A3AR antagonists as promising therapeutic choices for a range of diseases has been a prime subject of medicinal chemistry research. The pharmaceutical industry and academic communities have focused on the synthesis and screening evaluation of numerous heterocyclic compounds to discover potent and highly selective A3AR antagonists due to their potential therapeutic applications.144

A3AR antagonists belong to different structural groups including monocyclic, bicyclic, and tricyclic aromatic compounds (Table 3). Several xanthine or purine analogues were examined first, but none showed significant affinity or selectivity at rat A3AR.96,100,144,145 Consequently, different classes of compounds, that could be classified as nonxanthine derivatives135,144–149 and the lately nucleoside-derived antagonists, have been discovered as highly potent and selective A3AR antagonists.

TABLE 3.

Affinity of Selected A3AR Antagonists

| Compound | pKi value or % inhibition at 10 μM | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| A1AR | A2AAR | A3AR | ||

| Monocyclic systems | ||||

| 48155 | MRS1334 | 5.54 (r) | <10%(r) | 5.41 (r) |

| 8.57 (h) | ||||

| 49158 | MRS1505 | 4.38 (r) | 4.62 (r) | 6.09 (r) |

| 8.10 (h) | ||||

| 50162 | 17% (h) | 43%(h) | 8.46 (h) | |

| 51164 | ISVY130 | 1% (h) | 10% (h) | 8.44 (h) |

| 52165 | SYJA385 | 7% (h) | 10%(h) | 6.41 (h) |

| 53167 | 24% (h) | 28% (h) | 9.10 (h) | |

| 54146 | <5 (h) | <5 (h) | 9.39 (h) | |

| 55146 | <6.18 (h) | <6.08 (h) | 9.44 (h) | |

| 8.80 (r) | ||||

| Bicyclic systems | ||||

| 56169 | VUF5574 | 52% (r) | 43%(r) | 8.39 (h) |

| 57170 | 4% (h) | 1% (h) | 7.71 (h) | |

| 58171 | 0% (h) | 19%(h) | 9.11 (h) | |

| 59135 | 5.10 (h) | 6.08 (h) | 7.59 (h) | |

| 60173 | 6% (h) | 8%(h) | 7.60 (h) | |

| 61174 | 6.37 (h) | 5.09 (h) | 8.22 (h) | |

| 62175 | MRS3777 | 26% (h) | 16%(h) | 7.33 (h) |

| 63176 | 5.98 (h) | 5.50 (h) | 9.74 (h) | |

| 64176 | <5 (h) | <5 (h) | 8.54 (h) | |

| 65177 | 5% (h) | 1% (h) | 8.92 (h) | |

| 66179 | 1% (h) | 1%(h) | 10.57 (h) | |

| Tricyclic systems | ||||

| 67180 | CGS15943 | 8.46 (h) | 9.40 (h) | 7.02 (h) |

| 68182 | MRS1220 | 7.28 (r) | 8.00 (r) | 9.19 (h) |

| 69183 | <5 (h) | <5 (h) | 8.09 (h) | |

| 70184 | <6 (h) | 6.98 (h) | 8.94 (h) | |

| 71184 | <6 (h) | <6 (h) | 8.16 (h) | |

| 72185 | 42% (b) | 3% (b) | 8.68 (h) | |

| 73186 | <6 (h) | <6 (h) | 8.05 (h) | |

| 74188 | 25% (b) | 14% (b) | 8.33 (h) | |

| 0% (h) | ||||

| 75189 | 6.59 (b) | 0% (b) | 9.10 (h) | |

| 7.96 (h) | 2% (h) | |||

| 76190 | 0% (b) | 8.06 (b) | 8.68 (h) | |

| 77192 | 5.57 (h) | <5 (h) | 8.80 (h) | |

| 78193 | MRE3008-F20 | <5 (r) | 5.70 (r) | 9.54 (h) |

| 79203 | MRE3005-F20 | 6.60 (h) | 7.22 (h) | 10.40 (h) |

| 80149 | 5.47 (h) | <5.3 | 8.01 (h) | |

| 81204 | ND | ND | 79% (h) | |

| 82204 | ND | ND | 16% (h) | |

| 83196 | <6 (h) | <6 (h) | 7.74 (h) | |

| 84143 | 32% (h) | 49% (h) | 9.29 (h) | |

| 85143 | OT-7999 | 4% (h) | 31%(h) | 9.02 (h) |

| 86207 | PSB-10 | 5.77 (h) | 5.56 (h) | 9.36 (h) |

| 87209 | KF-26777 | 5.74 (h) | 6.33 (h) | 9.70 (h) |

| 88211 | 24% (h) | 0% (h) | 8.66 (h) | |

| 89200 | <6 (h) | <6 (h) | 9.10 (h) | |

| 90200 | <6 (h) | <6 (h) | 8.46 (h) | |

| 91195 | 5.60 (h) | <5.3 (h) | 8.84 (h) | |

| 92195 | 5.52 (h) | 5.82 (h) | 8.71 (h) | |

h, human; r, rat; and b, bovin.

ND = not determined.

In this section, we summarize the medicinal chemistry of A3AR antagonists updating our previous reviews on this field.150–153

4.3.1 Monocycles

1,4-Dihydropyridines and pyridines

After the first evidence that 1,4-dihydropyridines (DHPs) exerted antagonistic activity at the A3AR in addition to L-type calcium channel inhibition, Jacobson et al. designed a series of substituted DHPs in the attempt to separate the two different activities.154 In this study, the replacement of the methyl ester at the 5-position of nifedipine with a bulkier 4-nitrobenzyl ester, along with the introduction of phenylethynyl and phenyl moieties at positions 4 and 6, respectively, led to 48 (MRS1334, Fig. 4). This compound showed high affinity and selectivity as an A3AR antagonist without inhibiting L-type calcium channels.155 In addition, a 3,5-diacyl-2,4-dialkylpyridine series was delineated by the oxidation of the corresponding DHP derivatives, and the best profile against A3AR was achieved with 49 (MRS1505, Fig. 4) in which the position 4 of the pyridine ring was substituted with small alkyl groups such as ethyl chain.156,157 General SAR of pyridine derivatives revealed that structural requirements responsible for enhancement of A3AR affinity and selectivity did not completely reflect that of the DHP parent compounds.158 Among this series, were also reported fluorinated and hydroxylated pyridine derivatives159 and an extension of this study performed by Jacobson and co-workers described a series of N-alkylpyridinium salts as water soluble A3AR antagonists although with lower potency than the pyridine analogues.160 A pyridine-based A3AR antagonist PET ligand [18F]FE@SUPPY was introduced.161

FIGURE 4.

Monocycle-based A3AR antagonists

Pyrimidines

Within the classes of bi- and tricyclic ARs antagonists, the pyrimidine nucleus present in the endogenous modulator adenosine, is a frequent substructural scaffold. 4-Amino-6-hydroxy-2 mercaptopyrimidines derived from chain opening of a series of triazolopyrimidinones have been synthesized by Cosimelli et al.162 Introduction of the propylsulfanyl and p-chlorobenzyloxy moieties at 2 and 6 positions, respectively, combined with an acetamide group at 4-position of the pyrimidine ring led to compound 50 (Fig. 4), a potent and selective human A3R antagonist (Ki = 3.5 nM). Similar structures characterized by two regioisomeric series of diaryl 2- or 4-amidopyrimidines such as N-[2,6-bis(4-methoxyphenyl)pyrimidin-4-yl]acetamide 51 (ISVY130, Fig. 4) were reported by Sotelo and co-workers. Some of the ligands in this series exhibited good selectivity and affinity with Ki values of < 10 nM at the A3AR.163,164

Pyrazin-2(1H)-ones

Very recently, Sotelo and co-workers published a novel series of compounds, including a simplified pyrazin-2(1H)one scaffold, as A3AR antagonists and with better pharmacokinetic properties.165 These new derivatives obtained by the Ugi-based multicomponent reaction were less potent than many other A3AR antagonists reported in the literature. The entire library of compounds, including the most potent compound of this series with a Ki value of 386 nM (52, SYJA385, Fig. 4), was subjected to a computational study to determine a rational hypothesis for their binding model.165

Thiadiazole and thiazoles

IJzerman co-workers identified thiadiazole and thiazole analogues as A3AR antagonists by chemical structure simplification of corresponding bicyclic quinazoline and isoquinoline nuclei, respectively.166 Among them, compound N-[3-(4-methoxyphenyl)-[1,2,4]thiadiazol-5-yl]acetamide 53 (Fig. 4) was claimed as the best compound of the series exhibiting a Ki value of 0.79 nM and acting as antagonist in a cyclic AMP (cAMP) functional assay.167 SAR optimization by introduction of a 5-(pyridine)-4-yl moiety on the 2-aminothiazole ring revealed a series of potent and selective compounds such as N-[4-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)-5-(pyridin-4-yl)thiazol-2-yl]-acetamide 54, with subnanomolar affinity for human A3AR (Ki = 0.4 nM) and 1000-fold selectivity against the other AR subtypes.168

The QSAR analysis of thiazole and thiadiazole A3AR antagonists indicated that their binding affinity increased with decreasing lipophilicity and in the presence of small alkyl moieties such as amide functions (acetamide or propionamide).168 In addition, the introduction of substituents, such as benzoyl, nicotinoyl (e.g., compound 55, Fig. 4) and isonicotinoyl moieties in position 2 of the thiazole ring, led to potent and selective antagonists at both human and rat A3ARs.

4.3.2 Bicycles

Quinazolines, phthalazines, and quinoxalines

A structure–affinity study reported by IJzerman co-workers indicated that introduction of a phenyl or heteroaryl substituent on the 2-position of the quinazoline scaffold or the equivalent 3-position of the isoquinoline improved the A3AR affinity in comparison to the unsubstituted derivatives. Combinations of the best substituents in the two series led to the potent and selective human A3AR antagonist N-(2-methoxyphenyl)-N-(2-(pyridin-3-yl)quinazolin-4-yl)urea 56 (VUF5574; Fig. 5) with a Ki value of 4 nM. 169

FIGURE 5.

Bicycle-based A3AR antagonists

Subsequently, the 2-amino/2-oxoquinazoline-4-carboxamide compounds, resulting from an in silico molecular simplification approach of the 2-aryl-1,2,4-triazolo[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one skeleton, were published by Morizzo et al. as

A3AR antagonists. One example of this series is compound 57 (Fig. 5) that showed good affinity and selectivity at the A3AR.170 With a similar approach on the triazoloquinazolinone nucleus, a new series of 2-phenylphthalazin-ones was identified as promising A3AR antagonists. Molecular manipulations by introduction of amide and ureide functional groups at the 4-position of the phthalazinone ring led to compound 58 (Fig. 5) with the best activity profile.171 Additionally, the 2-(4-methyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)-quinoxaline 59 (Fig. 5) is noteworthy for the novelty of its design strategy utilizing a 3D database searching approach.172

Imidazo[1,2-a]pyrazines

Very recently, the imidazo[1,2-a]pyrazine nucleus was reported as a suitable core for the design of new AR antagonists. Within this series of compounds, a N-(2,6-diphenylimidazo[1,2-a]pyrazin-8-yl)-4-methoxybenzamide 60 (Fig. 5) showed good A3AR affinity with a Ki value of 25 nM. The molecular docking study of these compounds was also carried out to describe the potential binding mode of the new derivatives to their refined target receptor model.173

Adenines and adenine-like derivatives

The first class of selective A3ARantagonists characterized by a bicyclic structure strictly correlated to the adenine core was identified by Biagi et al.174 The adenine-like structure of these new N6-ureidosubstituted-2-phenyl-9-benzyl-8-azaadenines was responsible for their activity as antagonists, while the phenylcarbamoyl group ensured selectivity at the A3AR. The SAR studies based on the systematic substitutions of 2, 6, and 9 positions of the bicyclic system led to improved A1/A3 selectivity with compound 61 (Fig. 5).

Starting from reversine, 2-(4-morpholinoanilino)-N6-cyclohexyladenine, with a moderate activity as A3AR antagonists (Ki = 0.66 μM), Perreira et al. explored the SAR of related derivatives in order to improve A3AR potency and selectivity.175 A series of reversine analogues was synthesized by substitution of 2- and N6-positions of the adenine core. One of the most remarkable compounds in terms of hA3AR affinity and selectivity resulted when the N6-cyclohexyl moiety of reversine was combined with a 2-phenyloxy group (compound 62, MRS3777, Fig. 5).175 Some analogues from this study were shown to be inactive at 10 μM in the rat, reflecting the typical species dependence of binding of most known nonnucleoside A3AR antagonists.

The pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidine scaffold, a bicyclic system structurally connected to the adenine nucleus that resulted from simplification of tricycles pirazolo-triazolo-pyrimidine, was recently described by Taliani et al.176 The SAR profile of this series indicated that the presence of an amide or ureide functionality at the 4-position (compounds 63 and 64, respectively) along with a phenyl ring at the 6-position was essential for promoting A3AR affinity and selectivity. The N2-position was characterized by substantial steric tolerance; in fact, both small methyl group (63, Fig. 5) and bulkier benzyl moiety (64, Fig. 5) were well tolerated. Compound 63, which showed a subnanomolar A3AR affinity and high selectivity versus the other AR subtypes, has been suggested as a promising lead compound for the development of adjuvant agents in glioma chemotherapy. In a related effort, a series of junction isomers of pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidine derivatives were synthesized by Lenzi et al. applying a molecular simplification approach to the tricyclic pyrazolo[3,4-c]quinolin-4-one skeleton.177 The binding results of the junction isomers were successful and the new derivatives maintained high affinity for the hA3AR increasing also the selectivity versus the other AR subtypes. Aryl/arylalkyl substitution at the 5-position of such derivatives was poorly tolerated for A3AR binding affinity, while small groups at the same position were shown to enhance the ligand–receptor interaction. In addition, the substitution of the 2-phenyl ring with a 4-methoxy group led to 2-(4-methoxyphenyl)-5-methyl-2H-pyrazolo[4,3-d]pyrimidin-7(6H)-one 65 (Fig. 5), the most potent compound of this series. Very recently, a large number of 2-arylpyrazolo[4,3-d]pyrimidin-7-amine or 7-acylamine derivatives were synthesized as potent A3AR antagonists.178,179 The pyrazolopyrimidines bearing a 4-methoxyphenyl or a 2-thienyl group at the 5-position showed high hA3AR affinity and selectivity. 4-Methoxy-N-(2-phenyl-5-(thiophen-2-yl)-2H-pyrazolo[4,3-d]pyrimidin-7-yl)benzamide 66 (Ki = 0.027 nM, Fig. 5) is one of the most potent and selective A3AR antagonists in this structural class.179

4.3.3 Tricycles

Triazoloquinazoline

Jacobson and co-workers first described the N5-acylation of the free amino group of well-known 9-chloro-2-(furan-2-yl)-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-c]quinazoline-5-amine 67 (CGS15943, Fig. 6).180,181 This structural modification yielded 68 (MRS1220, Fig. 6), which was enhanced in both affinity and A3AR selectivity.181,182 The removal of the chlorine atom at 9-position of the triazoloquinazoline 67 along with the replacement of the 5-phenylacetamido and the 2-furyl moieties with a linear alkyl chain and a 4-Br-phenyl group, respectively, led to 69 (Fig. 6). This compound was found to be a potent and selective A3AR antagonist.183

FIGURE 6.

Tricycle-based A3AR antagonists

Very recently, a new series of triazoloquinazolines was reported as A3AR antagonists. Two examples are the 3,5-diphenyl[1,2,4]triazolo[4,3-c]quinazoline 70 (Ki =1.16 nM, Fig. 6) and the 5′-phenyl-1,2-dihydro-3′H-spiro[indole-3,2′-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-c]quinazolin]-2-one 71 (Ki = 6.94 nM, Fig. 6).184

Pyrazolo[3,4-c]/[4,3-c]quinolines

2-Arylpyrazolo[3,4-c]quinolin-4-ones, 4-amines, and 4-amino-substituted derivatives are reported as potent and selective hA3AR antagonists.185 Most of them showed a nanomolar hA3AR affinity and different degrees of selectivity that were strictly dependent on the presence and nature of the substituent on the 4-amino group. The benzoamide derivative 72 (Fig. 6) was the most potent and selective among the three reported series of compounds.

The pyrazole[4,3-c]quinoline-4-one scaffold was adapted to A3AR antagonists as structural isomers of the previous nucleus by Baraldi et al. Among the pyrazole[4,3-c]quinoline-4-ones, compounds that contained a 2-p-substituted phenyl (CH3, OCH3, and Cl) group showed good hA3AR affinity and excellent selectivity in comparison to the other AR subtypes (e.g., compound 73, Fig. 6).186

Triazolo[4,3-a]/[1,5-a]quinoxaline

Colotta et al. identified 1,2,4-triazolo[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one derivatives as promising hA3AR antagonists.187 The SAR study recognized the appropriate substitutions at 2, 4, and 6 positions of the tricyclic template. In particular, the introduction of the 4-oxo or 4-N-amide functions afforded selective and potent A3AR antagonists such as compounds 74188 and 75189, respectively, confirming the importance of both nuclear or extranuclear carbonyl functionality for A3AR affinity (Fig. 6). A series of 2-aryl-8-chloro-1,2,4-triazolo[1,5-a]quinoxalines has also been synthesized and evaluated in radioligand binding assay at both bovine and human ARs190,191 showing a similar SAR profile to that of the 2-arylpyrazolo[3,4/4,3-c]quinolines185, 186 and triazolo[4,3-a]quinoxaline.189 One of the representative derivatives was a 2-(4-methoxyphenyl)-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]quinoxalin-4(5H)-one 76 (Fig. 6).

1,2,3-Triazolo[1,2-a][1,2,4]benzotriazolones

A3AR antagonists based on aminophenyl-triazolobenzotriazinone have been reported by Da Settimo et al. A lead optimization strategy focused on the structural modifications provided that the suitable groups were attached to the 5-amino group and in the 4′-and/or 9-positions. The best result was obtained with compound 77 (Fig. 6), which showed a Ki value of 1.6 nM at the A3AR and no significant affinity at the other ARs.192

Pyrazolo[4,3-e]-1,2,4-triazolo[1,5-c]pyrimidines

The pyrazolo-triazolo-pyrimidine (PTP) scaffold, due to its strong structural correlation with the nonselective antagonists CGS15943 (67, Fig. 6) 180 and to the adenine nucleus present in the endogenous modulator adenosine, has been investigated in depth as a prototypical template for adenosine antagonists.

Rigorous research efforts were made on this scaffold in order to obtain potent A2A- and A3AR antagonists.153 A series of PTP derivatives (MRE series) reported by Baraldi’s group were obtained by the structure–activity optimization based on the introduction of different substituents at the 5, 7, 8, and 9 positions.145,149,193,194,196–200 The N7-substituted derivatives proved to be predominantly hA2AAR antagonists, while the combination of a small alkyl chain at the N8-pyrazole position with a (substituted)phenylcarbamoyl chain at the N5-position led to potent and selective hA3AR antagonists. 198 One of the most active and selective compounds in this series was 78 (MRE3008-F20, Fig. 7) with a Ki value of 0.29 nM.193 The corresponding tritium-labeled analogue as the first potent and selective radiolabeled antagonist for the A3AR was prepared. It bound to the hA3AR expressed in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells with a KD value of 0.82 nM (Bmax = 297 fmol/mg protein).201,202 The isosteric replacement of the phenyl ring with a 4-pyridylmoiety yielded 79 (MRE3005-F20, Fig. 7) that maintained the high affinity at the A3AR with enhanced water solubility.203 Subsequently, replacement of pyridin-4-ylmoiety of MRE3005-F20 with substituted piperidine rings led to the preparation of the hydrochloride salt of 1-(cyclohexylmethyl)piperidin-4-yl (80, Fig. 7).149

FIGURE 7.

Tricycle-based A3AR antagonists

Synthesis of fluorosulfonyl- and bis(β-chloroethyl)amino-phenylamino-pyrazolo[4,3-e]1,2,4-triazolo[1,5-c]pyrimidines as irreversible A3AR antagonists was performed by Baraldi’s group to provide useful tools for structure–activity studies. Electrophilic groups, specifically sulfonyl fluoride and nitrogen mustard (bis-(β-chloroethyl)amino) moieties, have been incorporated at the 4-position of the aryl urea group (compounds 81 and 82, respectively, Fig. 7).204 While compounds containing a fluorosulfonyl moiety proved to be irreversible antagonists at the hA3AR (at 100 nM, 79% of inhibition), the corresponding nitrogen mustard derivatives were unable to covalently bind the target receptor subtype. This difference in the receptor interaction between the 81 and 82 series has been explained on the basis of chemical reactivity of the two different groups.

Very recently a new series of N,N′-disubstituted guanidines of the PTP scaffold, prepared in a one-pot reaction, was described as A3AR antagonists. The best compound of this series was 83 (Fig. 7) bearing a N,N-(4-nitrophenyl)guanidine moiety at 5-position of the tricyclic nuleus.196

Triazolopurines

[1,2,4]Triazolo[5,1-i]purines structurally related to the triazoloquinazolines have been identified as A3AR antagonists.183,205 Within this family, the 5-n-butyl-8-(4-n-propoxyphenyl)-3H-[1,2,4]triazolo[5,1-i]purine 84 (Fig. 7) showed a good potency and selectivity at A3AR. Among the reported structures, compound 85 (OT-7999, Fig. 7) demonstrated a significant reduction of intraocular pressure in cynomolgus monkeys at 2–4 hr following topical application.205

Tricyclic xanthines

Caffeine and theophylline are the classical nonselective xanthine antagonists of ARs that display micromolar affinity at human AR subtypes. At the rat A3AR, caffeine and theophylline are weaker in affinity.

Initial SAR studies at the A3AR were carried out using multiple substituted xanthines, many of which retained selectivity for the A3AR.90 An interesting approach was based on the ring annelation of xanthine derivatives, which permitted several research groups to discover different tricyclic systems that showed dissimilar affinity to AR subtypes.206 A series of imidazo[2,1-i]purinones as tricyclic xanthines (PSB series) was developed by Müller et al. as human A3AR antagonists with improved water solubility.207 For example, 86 (PSB-10, Fig. 7) showed a subnanomolar A3AR affinity and a good selectivity compared to the other AR subtypes, and its tritiated form ([3H]PSB-11) exhibited a KD value of 4.9 nM (Bmax = 3500 fmol/mg of protein).208 Another similar compound is 2-(4-bromophenyl)-4-propyl-7,8-dihydro-1H-imidazo[2,1-i]purin-5(4H)-one 87, also designated KF-26777 (Fig. 7), was endowed with high affinity and selectivity.209

The pyrido[2,1-f]purine-2,4-diones, another series of tricyclic xanthines, have been reported to exert affinity at A3AR in the low nanomolar range. Different substituents at the 1 and 8 positions of the new scaffold were evaluated, and the SAR studies led to 3-(cyclopropylmethyl)-1-(4-methylbenzyl)pyrido[2,1-f]purine-2,4(1H,3H)-dione 88 (Fig. 7) showing the best A3AR binding profile of the series with total selectivity.210,211

Replacement of the pyridine nucleus of the pyrido[2,1-f]purine-2,4-dione scaffold with different 5-membered heterocycles has been extensively examined by Baraldi’s group. The SAR studies led to both series of pyrrolo[2,1-f]purine-2,4-dione and imidazo[2,1-f]purine-2,4-diones as A3AR antagonists.199 Among the examined molecules, the imidazo[2,1-f]purine-ones were 2- to 10-fold more potent than the corresponding pyrrolo[2,1-f]purine-ones (e.g., 89 vs. 90, respectively, Fig. 7) and the most favorable affinity and selectivity at A3AR was obtained by introduction of small alkyl chain at the 7-position of the main scaffold (compound 89).200

More recently, replacement of the trichlorophenyl ring at 2-position of PSB-10 86 and congeners with differently substituted five-membered heterocycles, like 1,3- and 1,5-disubstituted pyrazoles or 3-substituted isoxazoles (R-enantiomer 91 and 92, respectively, Fig. 7) was investigated by Baraldi’s group.195 The 2-heterocyclic substitution induced excellent affinity and selectivity for the hA3AR subtype. Docking of the most potent compound (91) in complex with a hA3ARhomology model furnished a general survey of the hypothetical binding mode of the newly described derivatives.195

4.4 Allosteric modulators of the A3 adenosine receptor

Allosteric modulators of GPCRs bind at a location that is distinct from the binding site for a native ligand, that is, the orthosteric site, and this phenomenon has been reported for the A3AR.212 In theory, the modulation may be positive, that is, with a PAM enhancing the activity of a directly acting (orthosteric) agonist, or negative, in the case of a NAM. A3AR PAMs have been shown to enhance the potency and/or efficacy of agonists. When administered in vivo, they would be expected to be silent, with respect to A3AR activity, unless either an endogenous or exogenous agonist would be present. Therefore, treatment with an A3AR-selective PAM might display greater event- or site-specific action than an exogenous agonist, because it would magnify the effect of locally released adenosine, that is, in response to stress of an organ or tissue.

The SAR of three classes of A3AR PAMs have been explored in detail: 1H-imidazo-[4,5-c]quinolin-4-amines (93 – 97),213–215 2,4-disubstituted quinolines (98), 216 and 3-(2-pyridinyl)isoquinolines (99, 100).217 Representative key members of these structural classes are shown in Figure 8. In addition to these heterocycles, allosteric modulation of this receptor by compounds and ions that are not specific to the A3AR, such as amiloride analogues and sodium, have been studied.212,218

FIGURE 8.

Allosteric modulators of the A3AR

The principal assay used to screen for allosteric modulators of the A3AR has been to examine effects on the dissociation rate of an agonist radioligand, [125I]I-AB-MECA 3.212 Many of the PAMs that have been reported also compete with the radioligand for specific binding. Thus, the objective in early studies was to identify lead molecules that impeded the dissociation rate, with minimal competitive binding potency.213,217 At a concentration of 10 μM, the imidazoquinolinamines and DU124182 93 and DU124183 94 reduced the dissociation rate of the radioligand from the receptor by roughly half, and the phenylamino derivative 94 was more potent as an allosteric enhancer.213 Dichloro substitution and expanding the cycloalkyl group in LUF6000 95, MRS5049 96, and MRS5190 97 were later shown to produce potent allosteric enhancement with less prominent competitive inhibition.214,215 An amide LUF6096 98 was particularly selective for allosteric enhancement of the A3AR compared to 95, but it displayed a short half-life in vivo. The residues of the A3AR that are associated with the allosteric enhancement compared to orthosteric ligand binding were probed using stite-directed mutagenesis.218

When multiple effector mechanisms induced by agonist Cl-IB-MECA were compared, 95 was found to modulate each activity in a different manner, that is, this imidazoquinolinamine appeared to be a functionally biased PAM.108,219 For example, 95 had no effect on phosphorylation of ERK1/2, a small effect on β-arrestin2 translocation, and intense effects on cAMP inhibition and cell hyperpolarization. The agonist-enhancing effect of 95 was probe-dependent, that is, it had different degrees of modulation of different AR agonists, considered receptor “probes.” Notably, 95 greatly increased the efficacy of the naturally occurring nucleoside inosine, which is normally a weak and only partially efficacious agonist at the A3AR. Inosine is a metabolite of adenosine and, like adenosine, is elevated in concentration when stress to an organ is present. Thus, 95 could produce therapeutic benefit in vivo partially from its enhancing action on inosine, as well as endogenous adenosine. 95 also enhanced the efficacy of nucleoside antagonists of the A3AR, such as MRS542 38, to produce full agonism at the A3AR. This indicates that nucleoside antagonists might behave as antagonists in a given functional model, but there is a latent agonism that can be amplified in the presence of a PAM. In contrast, nonnucleoside A3AR antagonists did not display any latent agonism in the presence of an A3AR PAM.

LUF6000 95 has anti-inflammatory effects in rat models of arthritis and a model of liver inflammation in mice,220 suggesting its potential use in the treatment of autoimmune inflammatory diseases. LUF6096 98 was shown to protect the heart in a model of canine cardiac ischemia,218 suggesting the potential use of A3AR PAMs in the treatment of ischemic conditions.

4.5 Structural characterization of the A3 adenosine receptor

Although there is currently no X-ray crystallographic structure of the A3AR available, effective use of modeling techniques has provided a window into its orthosteric binding site (Fig. 9). In particular, docking of agonists in conjunction with data from site-directed mutagenesis has demonstrated the close similarity of the A3AR to the X-ray crystallographic structure of the hA2AAR.221 Complexes of the A2AAR with four different agonists, namely 6-(2,2-diphenylethylamino)-9-((2R,3R,4S,5S)-5-(ethylcarbamoyl)-3,4-dihydroxytetrahydrofuran-2-yl)-N-(2-(3-(1-(pyridin-2-yl)piperidin-4-yl)ureido)ethyl)-9H-purine-2-carboxamide (UK432,097); adenosine; 5′-Nethylcarboxamidoadenosine (NECA); and 2-[p-(2-carboxyethyl)phenylethyl-amino]-5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (CGS21680) (PDB IDs: 3QAK, 2YDO, 2YDV and 4UG2, respectively), have been crystallized and their structures determined.222–224 The complexes revealed a common interaction pattern anchoring the adenosine moiety in the orthosteric binding site of the A2AAR involving several conserved amino acid residues that are predicted to serve the same function in the A3AR binding site. For example, the side chain Asn6.55 (using standard notation for numbering of TMs225) coordinates by H-bonding in a bidentate fashion with the adenine N6H and N7 in both ARs. His7.43 is in contact with the 2′-hydroxyl group of ribose. Also, Phe168 (EL2) is predicted to form π–π stacking with the adenine ring, as in the A2AAR. However, there are some differences in the interaction of nucleoside ligands with A3AR compared to A2AAR that account for pharmacological differences of such ligands, with respect to their affinity, selectivity, and efficacy. For example, His6.52, which forms an H-bond to the 5′-carbonyl group of potent A2AAR agonists occurs as Ser6.52 in the A3AR and is not predicted to closely associate with typical nucleoside ligands. This might explain why binding of 4′-truncated nucleosides is maintained at the A3AR relative to other ARs.

FIGURE 9.

(A) Docking pose of 3,4-difluorophenyl agonist analogue MRS5980 (27) at the hA3AR homology model, in which TM2 is based on its position in the active β2 adrenergic receptor. Residues interacting with the ligand (magenta carbon atoms) are labeled. H-bond and π–π interactions are represented as green solid and cyan dashed lines, respectively. Nonconserved ARs residues are in italics. (B) Docking pose of biphenyl agonist analogue MRS5679 (26) at the hA3AR homology model. Residues interacting with the ligand (violet carbon atoms) are labeled and H-bond interactions are represented as green solid lines. The degree of displacement of TM2 with respect to the TM bundle in hA3AR homology models based on the hA2AAR (red ribbon), hybrid hA2AAR-β2 adrenergic receptor (purple ribbon), and hybrid hA2AAR-opsin (violet ribbon) templates is highlighted with an arrow. TM1 is omitted to aid visualization

Conformational plasticity of the A3AR has been proposed to account for the high-affinity binding of rigid C2-arylalkynyl agonists such as MRS5980 27.120 When docking this class of compounds in a homology model of the A3AR derived exclusively from the agonist-bound “active-like” A2AAR structure, there was a steric clash with the extracellular tip of TM2. An outward movement of TM2, as observed in several other active GPCR structures such as the β2-adrenergic receptor and opsin, was therefore hypothesized to occur also for the A3AR. Thus, a hybrid homology model in which TM2 assumed its highly displaced position in opsin was required to dock biphenyl derivative MRS5679 26, and the other TMs followed their orientation in the agonist-bound A2AAR.226 This proposed outward movement of TM2 was also associated with the degree of activational bias of C2-extended A3AR agonists for cell survival, in a comparison of five different functional readouts.131

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation of the A3AR in complex with agonists have been reported.227 The analysis of the conformational changes of conserved Trp243 (6.48) as a result of agonist (Cl-IB-MECA) binding suggested that the ligand was able to promote and stabilize an expected conformational switch involved in receptor activation.

A supervised MD (SuMD) study simulated the approach of PAM LUF6000 95 toward a putative allosteric binding site on the A3AR that contained an adenosine molecule in the orthosteric site.228 In the modeled ternary complex, 95 occupied the upper region of the orthosteric binding site by directly interacting with the agonist. The study suggested that 95 might exert its PAM activity by acting as “pocket cap.”

GPCRs may form characteristic dimers, either homo- or heterodimers, and the pharmacological implications of such dimerization remain to be fully characterized. Homodimers of the A3AR have been detected using fluorescent methods.229 Indications are that in the future, the discovery of A3AR ligands will rely heavily on computational methods to define the dynamic interaction of the receptor with its ligands and with other proteins, including other GPCR protomers.

5 INTRACELLULAR PATHWAYS IN IMMUNE AND CANCER CELLS

A schematic diagram showing the main signaling pathways triggered by adenosine through A3AR activation in different cellular types is reported in Figure 10. The A3AR preferentially couples to Gi protein to inhibit cAMP accumulation, and it may also couple to Gq protein to mediate stimulation of phospholipase C (PLC), which then increases calcium concentrations.230 The activation of PLC, and even the Ca2+ effects observed at high concentrations of A3AR agonists, could conceivably be triggered by mechanisms other than Gq, such as Gβγ subunits. In addition, a Gq protein kinase C (PKC) dependent mechanism has been related to the apoptosis-inducing factor upregulation mediated by high doses of adenosine and of an A3AR agonist in a human bladder cancer cell line.78 However, PKC was recruited by A3AR stimulation in order to increase tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) release in activated macrophages.231

FIGURE 10.

Intracellular pathways of A3AR in immune and cancer cells. Schematic diagram showing the main signaling pathways triggered by adenosine through A3AR activation in different cellular types. A3AR preferentially couples to Gi. PLC activation, and even the Ca2+ effects observed at high concentrations of A3AR agonists, could conceivably be triggered by mechanisms other than Gq, such as Gβγ subunits

A huge amount of data supports a link between A3AR and MAPKs in several cellular models.232 A3AR-mediated activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK1/2) and mitogenesis modulation was found in human fetal astrocytes, CHO cells expressing the human A3AR (CHO-hA3), microglia, colon carcinoma, glioblastoma, melanoma and in foam cells.43,74,233–240 However, an inhibition of ERK activation has been revealed in A375 melanoma, prostate cancer, and glioma cells, leading to a reduction of cell proliferation as well as a decrease of TNF-α release in RAW 264.7 cells.22,73,241,242 The A3AR also activates p38 MAPKs in different cellular models including CHO-hA3, hypoxic melanoma, glioblastoma, and colon carcinoma cells,235,237,243 while reducing p38 MAPKs in human synoviocytes.53 Concerning c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), its activation by A3AR has been retrieved in microglia and glioblastoma cells, leading to cell migration and matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) stimulation, respectively.74,244 MEK/ERK1/2 and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways downstream of the A3AR control multiple resistance-associated protein 1 (MRP1) transporter substrate in glioblastoma cells, demonstrating a chemosensitizing effect by pharmacological blockade of A3AR and consequent reduction in tumor size.245

A pathway involving Akt phosphorylation protects RBL-2H3 and glioblastoma cells from apoptosis, while the same pathway produced an antiproliferative effect and increase in MMP-9 in A375 and glioblastoma cells, respectively.74,236,246,247 On the other hand, A3AR-mediated activation of the phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt signaling pathway enhances pigmentation in B16melanoma cells and in human skin explants.85

The PI3K/Akt and nuclear factor (NF) κB signaling pathways are the mediators of the anti-inflammatory A3AR-mediated effects, as observed in activated BV2 microglial cells, monocytes, adjuvant-induced arthritis, and in mesothelioma.75,248–253 Akt inhibition is involved in the reduction of A3AR-mediated of hypoxia inducible factor 1 (HIF-1α) accumulation in murine astrocytes.254 In addition, the block of PI3K/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling through A3AR suppresses angiogenesis in endothelial cells.127

Furthermore, an A3AR-mediated decrease in the protein kinase A (PKA) level was responsible for: (i) an increase in glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK-3β), leading to a downregulation of beta-catenin and its transcriptional gene products cyclin D1 and c-Myc, and (ii) a decrease in the level of NF-κB DNA-binding capacity. This effect through A3AR activation has been reported in melanoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, synoviocytes from RA patients, and in adjuvant-induced arthritis rats.89,255–257 Interestingly, a downregulation of A3AR mRNA/protein expression in colon cells after ulcerative colitis by miR-206 led to an increase of NF-κB and the downstream cytokine (TNF-α/IL-8/IL-1β) expression in the mouse colon, producing a proinflammatory effect.19

6. BIOLOGICAL ROLE AND THERAPEUTIC APPLICATIONS IN MODELS OF IMMUNE DISORDERS AND CANCER

6.1 Preclinical studies in immune cells

The A3AR is expressed in almost all cells of the immune system acting as essential mediators of adenosine’s role in inflammation.258–260

A growing body of evidence suggests a key role of the A3AR in neutrophil behavior. In recent years, it has been reported that the A3AR is distributed in a highly polarized fashion on the neutrophils cell membrane and contribute to their chemotaxis and migration. Specifically, A3AR is translocated to the neutrophil leading edge, and adenosine generated by ecto-ATPases/nucleotidases results in autocrine stimulation of A3AR-enhanced polarized migration, following its initiation by ATP activating the P2Y2 receptor.34,261–263 This was confirmed also in a sepsis model of A3ARknockout (KO) mice where a reduction in the recruitment of neutrophils to the lung and peritoneum was observed.264 In contrast, in human breast cancer cells, the A3AR is expressed in multiple leading edges where it promotes cell migration with numerous directional changes. Indeed, exogenous adenosine may simultaneously stimulate A3AR on all leading edges of the cell, inducing it to spread out in opposing directions resulting in arrest of cell motility.263 Furthermore, it has been found that the endogenous A3AR aggregates into plaque-like microdomains that affect cytoskeletal remodeling. In addition, they promote the formation of membrane protrusions, also named cytonemes, which enable neutrophils to capture pathogens.36 In contrast, data in early literature reported that chemotaxis and, in addition, oxidative burst were inhibited by A3AR activation with anti-inflammatory effects.32,33,35

Adenosine modulates monocyte-macrophage functions, being responsible for both inflammatory mediator production and resolution induction. For example, A3AR stimulation inhibits the respiratory burst, interleukin (IL) 1β, TNF-α, chemokine macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP) 1α, interferon regulatory factor 1, iNOS (inducible nitric oxide synthase), and CD36 gene expression.38,40,41,249,265–267 However, adenosine reduced the expression of adhesion molecules on monocytes and decreased cytokine production, effects that were potentiated by an A3AR antagonist.268 In addition, A3AR stimulation increased TNF-α production in activated macrophages.231

A functional A3AR is expressed in dendritic cells, antigen-presenting entities activating naive T lymphocytes and starting primary immune responses.269,270 In particular, the A3AR in the human immature elements has been found to induce elevated Ca2+ levels, actin polymerization, and chemotaxis, while in mature dendritic cells, the A3AR is down-regulated and decreases TNF-α release.44,46

T cells represent the major actors in adaptive immunity and play a crucial role in the battle against infections and tumors. Both cytotoxic (CD8+) and helper (CD4+) T cells express A3AR.48,271 Initial studies attributed to the A3AR an immunosuppressive role toward T cell mediated immune responses, but the mechanisms involved have not been investigated.272,273 Interestingly, oral administration of an A3AR agonist increased the cytotoxic activity of mouse NK cells and serum IL-12, thus reducing in vivo growth of melanoma cells.274 Indeed, ex vivo activation of CD8+ T cells with an A3AR agonist improves adoptive immunotherapy for melanoma.275 A3AR has been found to be upregulated in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) obtained from patients affected by different autoimmune disorders such as RA, Crohn’s disease, and psoriasis. This effect has been ascribed to the increase of TNF-α resulting in an upregulation of NF-κB and the cAMP response element binding protein (CREB), acting as A3AR transcription factors.276 Therefore, A3AR could be indicated as a biological predictive marker in autoimmune inflammatory pathologies. Furthermore, an immunosuppressive effect has been confirmed in lymphocytes derived from patients affected by RA, where the A3AR, upregulated with respect to healthy subjects, inhibited the NF-κB signaling, inflammatory cytokines, and MMPs production. Their density inversely correlated with indexes used to assess RA disease activity, supporting the importance of A3AR in the control of RA joint inflammation.277 Furthermore, A3AR activation in rat models hampered damage of cartilage, formation of osteoclast/osteophyte, bone destruction, and generation of pannus and of lymphocyte formation.278,279 Similarly, an A3AR anti-inflammatory effect, that is, NF-κB-TNF-α-dependent has also been found in synoviocytes of RA patients.257 Interestingly, this mechanism has been suggested also in A3AR-induced hepatoprotection against ischemia/reperfusion (IR) injury.280

The A3ARhas long been recognized as a major contributor of rodent mast cell activation by increasing their degranulation and, more recently, this factor has been observed also in both primary human and LAD2 mast cells.9,13,63,82–84,281 A3AR activation with an agonist significantly increased IL6, IL8, VEGF, amphiregulin, and osteopontin genes in human mast cells, affecting severe asthma.285,286 Indeed, prolonged treatment with an agonist produced A3AR downregulation responsible for the suppression of its basal inhibitory effect on cytokine production. This response was obtained only at a transcriptional level, suggesting that, at variance with rodents, in humans the primary role of the A3AR is to act as a modulator rather than a stimulator of mast cell responses.287

Activation of the A3AR induced hypothermia through the induction of mast cell degranulation, consequent histamine release, and activation of central histamine H1 receptors.288

6.2 Preclinical studies in cancer cells