Abstract

Appalachia has a higher incidence of and mortality from colon cancer (CC) than other regions of the United States; thus, it is important to know the potential impact of elevated risk on cancer worry. Guided by the Self-regulation model, we investigated the association of demographic, cultural (e.g., fatalism, religious commitment), and psychological factors (e.g., perceived risk, general mood) with CC worry among a sample of Appalachian women. A mixed method design was utilized. Appalachian women completed surveys in the quantitative section (n = 134) and semi-structured interviews in the qualitative section (n = 24). Logistic regression was employed to calculate odds ratios (OR) for quantitative data, and immersion/crystallization was utilized to analyze qualitative data. In the quantitative section, 45% of the participants expressed some degree of CC worry. CC worry was associated with higher than high school education (OR 3.63), absolute perceived risk for CC (OR 5.82), high anxiety (OR 4.68), and awareness of easy access (OR 3.98) or difficult access (OR 3.18) to health care specialists as compared to not being aware of the access there was no association between CC worry and adherence to CC screening guidelines. The qualitative section revealed fear, disengagement, depression, shock, and worry. Additionally, embarrassment, discomfort, and worry were reported with regard to CC screening. Fears included having to wear a colostomy bag and being a burden on family. CC worry was common in Appalachians and associated with higher perceptions of risk for CC and general anxiety, but not with adherence to screening guidelines. The mixed method design allowed for enhanced understanding of CC-related feelings, especially CC worry, including social/contextual fears.

Keywords: Colon cancer, Appalachian region, Worry, Rural health, Perceived risk

Introduction

Although colon cancer (CC) is preventable through routine screening [1], it is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer and the third leading cause of cancer mortality in the United States (US) [2]. Residents of Appalachia experience higher CC incidence [3] and mortality rates [4] as compared with the rates from the US general population. Appalachia is a geo-politically defined region that extends over 13 states and includes approximately 25 million people or 8.2% of the US population [5]. Approximately 10% of Appalachians reside in rural areas, and Appalachia is disproportionately rural [5]. As a group, Appalachians have lower educational attainment and limited access to health care, in comparison to the US population [6]. As socio-economic status and insufficiency of health care services are key components of overall health and well-being [7] and Appalachia has elevated CC incidence, the rural Appalachian population is worthy of study to understand the impact of being medically-underserved on CC.

Unfamiliarity with CC screening guidelines [8], poor adherence to the guidelines [9], elevated cervical cancer worry [10], and poor overall well-being and mental health [11] are factors associated with being from a medically-underserved region in rural Appalachia. Although the effect of CC worry on adherence to CC screening guidelines is sometimes conflicting [9], growing evidence shows that greater worry may impede screening behavior, especially in the absence of a clear and effective action plan to avoid threats [10, 12]. Examining CC worry is particularly important where screening barriers are common, such as in rural Appalachia.

Given elevated incidence of advanced CC and CC mortality in Appalachia, CC worry may negatively influence overall health as well as engagement in CC screening. Therefore, there is a need to understand the factors associated with CC worry. This may be especially salient in women as they are more likely to report cancer worry than men [13]. Thus, Study 1 was a quantitative study to investigate the association between a range of cultural, demographic, and psychological variables and CC worry in rural Appalachia women, and Study 2 was a qualitative study to understand a broader range of emotions about CC and CC screening.

Conceptual Framework

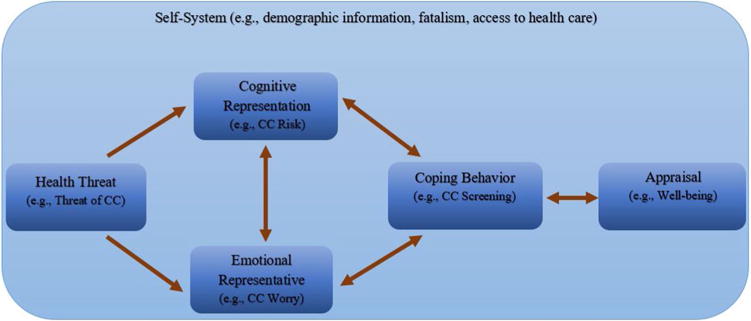

We utilized the Self-Regulation Model (SRM) as a theoretical framework in this study. The SRM is a widely used conceptual model for explaining how people respond to health threats (Fig. 1) [14]. According to the SRM, when individuals are confronted with a potential health threat like CC, they form a cognitive representation of the disease (e.g., perceived risk) and an emotional representation (e.g., CC worry) that may interact to motivate engaging in coping strategies (e.g., praying or using religious coping; engagement in preventive screening). The outcome of such coping is an appraisal of health, often measured as well-being or self-reported health. This process occurs in the context of self and social environment, which includes demographic, cultural, and dispositional factors (e.g., education, health access) [15]. As the model is self-regulatory, these processes operate in a feedback loop that is responsive to each of the elements of the model. The SRM is widely used to examine worry and health behavior and was informative when applied to studies on residents of Appalachia [10].

Fig. 1.

The self-regulation model

Because the focus of this paper was about CC worry as a form of emotional representation, we were interested in the relations between CC worry and other components of the SRM. In terms of self-system factors, many researchers have speculated that fatalism, a belief that death is an unavoidable consequence to cancer, is a key player in poorer adherence to cancer screening in Appalachia (e.g., [16]). Further, people living in isolated or rural localities, such as Appalachians, may express more cancer worry due to limited access to health care [17].

In terms of cognitive representation, research has demonstrated that CC worry is positively associated with higher perceived risk of cancer [18], just as cervical cancer worry was associated with higher perceived risk of cervical cancer in Appalachian women [10]. In terms of coping behavior, religiosity plays a significant role in the Appalachian culture [19], especially in behaviors pertaining to cancer care [20]. In our quantitative study, we expected limited health care access, higher perceived risk, lower general well-being, and less religious commitment to be associated with greater CC worry. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to understand the role of SRM factors in cancer worry and the larger representation of emotion. For a more comprehensive understanding of CC worry in Appalachia, our research was based on a mixed method design [21], particularly to learn more about CC worry. This mixed method design helped in augmenting the richness of the data to better understand CC in the Appalachian region.

Study 1 Methods

Design

Our quantitative study aimed to investigate the association between a range of cultural, demographic, and psychological variables and CC worry, based on the SRM. Collecting qualitative and quantitative data allowed for more in-depth knowledge of CC and CC screening in Appalachia, especially regarding CC worry.

Participants

Participants were women who were 18 years of age or older (n = 134) from rural, Appalachian Ohio. This study was part of a larger study that investigated cervical and CC screening [14]. We excluded pregnant women, women with a personal history of cancer, and women who did not complete survey items related to the primary variable of interest (CC worry).

Procedures

We obtained an Institutional Review Board approval from our institution. Medical records in a local health department were reviewed by study personnel to determine eligibility. Participants were randomly selected from eligible records and mailed a letter allowing them to ‘opt out’ of the study by return mailing a postcard. A survey packet including a letter from the health department clinic, consent form, structured questionnaire, HIPAA form, and reimbursement form was mailed to those who did not opt out. To improve the response rate, participants were also recruited from a federally qualified health clinic.

Measures

To better understand self-system factors, we collected demographic information including age, education, race, ethnicity, income, and health insurance in order to better understand the self-system factors. Perceived Appalachian identity and specialty health care access was assessed with single-item, binary response measures (Yes, No). Fatalism was evaluated using the Powe Fatalism Index [22].

For the cognitive representation of CC, we measured absolute perceived risk with one item to assess participant’s perceived chances of getting CC in the future using a 4-point Likert-type response format (not at all-definitely) consistent with previous research [10]. We assessed comparative perceived risk using one item, which asked the participants about their lifetime perceived likelihood of getting CC in comparison with women of the same age, using a 5-point Likert-type response consistent with previous research [23]. Regarding the emotional representation of CC, we assessed cancer worry with a modified version of the Cancer Worry Scale adapted to CC [24], using a 4-point Likert-type response format (not at all-a lot). We dichotomized responses to cancer worry; participants were divided into two groups: the ‘No Worry’ group (for those who reported ‘not at all’ on all four items of this scale) and the ‘Worry’ group (for those who reported some worry on at least one item). This “all or none” way of grouping was based on prior research findings regarding the detrimental influence of any episodes of worry on physiological function of individuals [25]. To assess coping, we assessed religiosity using the Religious Commitment Inventory short-form [26]. We also assessed self-reported CC screening behavior [1].

Two measures assessed overall well-being. The short-form of the Profile of Mood States [27] encompasses six attributes of general mood: tension, anger, depression, confusion, vigor, and fatigue with a 5-point Likert response format (not at all-very much). Further, self-assessed health over the past 4 weeks (poor-very good) served as a measure of general well-being, consistent with previous research [28].

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were conducted to examine the basic characteristics of the sample. Among the age-eligible participants (50–75 years old), we examined screening history to identify adherence to the screening guidelines [1]. Chi square analysis was conducted between CC worry and adherence to CC screening guidelines. Furthermore, we examined the bivariate analyses (Chi-Square and independent sample t Test) to check the association of any independent variables with CC worry. Bivariate analyses identified factors likely to show significant associations to include in the subsequent logistic regression model analysis. Variables that showed a p-value of equal or less than 0.1 in bivariate analyses were subsequently added in the final binary logistic regression model. We conducted the analysis using backward stepwise selection. SPSS v.22 was used to conduct analyses.

Study 1 Results

Sample

Of 281 women contacted from a local health department, 73 participants completed and return mailed the surveys, reflecting an initial response rate of 26%. An additional sample of 64 participants were recruited from a federally-qualified health clinic with a participation rate of 93%. The sample (n = 137) reflected an overall response rate of 39%, with 3 removed due to ineligibility (final sample n = 134). Table 1 includes the demographic information about the sample. Among these screening-aged participants, approximately half were adherent to screening guidelines, relatively low compared to 62.8% adherence rate in Ohio [29].

Table 1.

Quantitative section. Sample characteristics of Appalachian women (N = 134)

| Number | Percentage (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 19–29 | 34 | 25 | |

| 30–39 | 28 | 21 | |

| 40–49 | 29 | 22 | |

| ≥50 | 33 | 25 | |

| Missing | 10 | 7 | |

| Education level | |||

| GED, 12th grade, or less (Preschool—11th grade) | 77 | 57 | |

| Technical, trade degree, associate, bachelor’s, master’s, professional, doctorate degrees, or some years of that | 57 | 43 | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 1 | 1 | |

| Non-Hispanic | 133 | 99 | |

| Race | |||

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 2 | 1 | |

| Black or African American | 9 | 7 | |

| white | 118 | 88 | |

| Other | 5 | 4 | |

| Poverty | |||

| Below the poverty line | 88 | 66 | |

| Above the poverty line | 46 | 34 | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 38 | 28 | |

| Divorced, widowed, separated | 54 | 40 | |

| Single, never been married, or a member of unmarried couple | 41 | 31 | |

| Missing | 1 | 1 | |

| Health insurance | |||

| No | 31 | 23 | |

| Yes | 103 | 77 | |

| Belong to a religious organization | |||

| No | 80 | 60 | |

| Yes | 51 | 38 | |

| Missing | 3 | 2 | |

| Annual income in dollars ($) | |||

| ≤10,000 | 64 | 48 | |

| 10,001–20,000 | 40 | 30 | |

| ≥20,001 | 30 | 22 | |

| Occupational status | |||

| Employed | 56 | 42 | |

| Unemployed, retired, or disabled | 61 | 46 | |

| Housewife or student | 16 | 12 | |

| Missing | 1 | 1 | |

| Access to gastroenterologist | |||

| Easy | 22 | 16 | |

| Neither easy nor difficult/do not know | 76 | 57 | |

| Difficult | 34 | 25 | |

| Missing | 2 | 1 | |

| Self-assessed health | |||

| Excellent, very good, or good | 72 | 54 | |

| Fair, poor, or very poor | 61 | 46 | |

| Missing | 1 | 1 | |

| CC worry | |||

| No worry | 74 | 55 | |

| Some worry | 60 | 45 |

Associations with Worry

Nearly half of our participants expressed some CC worry (45%). Even though participants who were adherent to the guidelines were more likely to express CC related worry, the results of the Chi square analysis showed no significant association [x2(1, 33) = 1.56, p = .21]. The bivariate analyses indicated that eight variables were significantly associated at values of p ≤ .1 with CC worry (Table 2). Next, we added those eight variables into the final binary logistic model. Variables that were significantly associated (at values of p ≤ .05) with higher CC worry were: higher education, having easy or difficult access to gastroenterologist, higher absolute perceived likelihood of having CC, and higher general anxiety. Beta values, confidence intervals, and other details about the binary logistic regression model results are shown below (Table 3).

Table 2.

Quantitative section. Categorical and continuous variables significantly related to CC worry: bivariate analysis

| Variable | No worry (row%) | Some worry (row%) | Test statistics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Education level | |||

| GED or 12th grade, or less (preschool, Kindergarten—11th grade) | 48 (62%) | 29 (38%) | x2 (1, N = 134) = 3.71, p = .05 |

| Technical, trade degree, associate, bachelor’s, master’s, professional, doctorate degrees, or some years of that | 26 (46%) | 31 (54%) | |

| Occupational status | |||

| Employed | 37 (66%) | 19 (34%) | x2 (2, N = 133) = 4.96, p = .08 |

| Unemployed, retired, or disabled | 29 (48%) | 32 (52%) | |

| Housewife or student | 7 (44%) | 9 (56%) | |

| Access to gastroenterologist | |||

| Easy | 9 (41%) | 13 (59%) | x2 (2, N = 132) = 9.17, p = .01 |

| Neither easy nor difficult/do not know | 50 (66%) | 26 (34%) | |

| Difficult | 13 (38%) | 21 (62%) | |

| Comparative likelihood of getting CC in lifetime | |||

| Below average or much below average | 28 (78%) | 8 (22%) | x2 (2, N = 130) = 14.54, p < .001 |

| Same | 38 (53%) | 34 (47%) | |

| Above average or much above average | 6 (27%) | 16 (73%) | |

| Absolute likelihood of having CC | |||

| No, not at all | 32 (82%) | 7 (18%) | x2 (1, N = 129) = 16.48, p < .001 |

| Yes, there is likelihood | 39 (43%) | 51 (57%) | |

| Profile of mood states (POMS) | |||

| Anxiety sub-scale | M = 1.48 (SD = 0.34) | M = 1.61 (SD = 0.34) | t (132) = −2.17, p = .03 |

| Confusion sub-scale | M = 1.41 (SD = 0.25) | M = 1.49 (SD = 0.29) | t (132) = −1.74, p = .08 |

| Fatigue sub-scale | M = 2.62 (SD = 1.12) | M = 2.96 (SD = 1.17) | t (132) = −1.68, p = .09 |

x2 chi square, N number of subjects included in the analysis, p significance level or p-value, M mean, SD standard deviation, t t test

Table 3.

Quantitative section. Significant variables in the final logistic regression equation model

| Variable | B | SE | p | OR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education | ||||||

| Lower | 1 | – | ||||

| Higher | 1.289 | 0.464 | 0.005 | 3.630 (1.46–9.01) | ||

| Access to gastroenterologist | ||||||

| Neither easy nor difficult/do not know | 1 | – | ||||

| Easy | 1.380 | 0.577 | 0.017 | 3.975 (1.28–12.31) | ||

| Difficult | 1.155 | 0.501 | 0.021 | 3.175 (1.19–8.48) | ||

| Absolute perceived risk of having CC | ||||||

| No, not at all | 1 | – | – | – | ||

| Yes, there is at least some likelihood | 1.761 | 0.533 | <0.001 | 5.818 (2.05–16.52) | ||

| Profile of mood states (POMS) anxiety sub-scale | 1.544 | 0.677 | 0.023 | 4.684 (1.24–17.65) |

B regression coefficient, SE standard error, p significance level or p-value, OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval

Study 2 Methods

Design

Our qualitative study aimed to better understand feelings about CC and CC screening in a sample of women recruited from rural Appalachian counties. During semi-structured interviews, patients expressed their emotional representation (i.e., personal feelings) about CC and CC screening. Interviews were held individually with every participant. We began interviewing participants for the qualitative potion of the study before we began the quantitative portion and continued to interview participants for the qualitative portion after we concluded the quantitative portion. The SRM model guided constructing the semi-structured survey open-ended questions. We utilized Methodological Triangulation to integrate the findings from both portions and yield more meaningful interpretations of the study findings [21].

Participants

Participants were women (n = 24) who were at least 18 years old and recruited from rural Appalachian counties in Ohio.

Procedures

We obtained an Institutional Review Board approval from our institution and started each interview with signing an informed consent agreement. Advertisements at senior centers invited participants to call a 1-800 telephone number. Additionally, we mailed solicitations and re-contacted participants after participating in a previous research study. We started each interview with signing an informed consent form, followed by a brief questionnaire and semi-structured interview. Men were given a $20 gift card for participating.

Measures

We collected demographic information including age, education, race, ethnicity, income, and health insurance in order to better understand self-system factors with single-item measures. Appalachian identity was assessed using one item with a binary response (Yes, No). Self-assessed health over the past 4 weeks served as a measure of general well-being (poor–very good) [28]. Feelings about CC and CC screening were assessed through prompting participants with two semi-structured questions.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were conducted to examine the basic characteristics of the sample. We utilized immersion/crystallization, in which researchers immerse themselves in the data by examining details thoroughly, then temporarily suspending the immersion process to have an overall preview (i.e., crystallization) in order to understand the data [30]. Immersion/crystallization can be used with pre-existing theory, such as the SRM [31]. The SRM guided open-ended questions and helped in revealing the psychological states behind the participants’ feelings. Semi-structured interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed. Transcripts were reviewed and relevant ideas were extracted to develop a coding scheme. Using line-by-line coding, codes were attached to relevant text. Codes were grouped into themes depending on the context and as they related to the SRM.

Study 2 Results

Sample

Ages ranged from 22 to 64 years, with a mean age of 43.5 years. One individual identified as African American. Even though all participants were from an Appalachian county, only eight identified as Appalachians. The majority (58.3%) had a high school degree or less, 66.7% had household incomes below $25,000, and 30% did not have health insurance. The mean rating for self-assess health was 2.7, which corresponds to between ‘fair’ and ‘good’ on the scale.

Emotional Representation of CC

The feelings regarding CC included fear, depression, disengagement, shock, and worry. Many participants believed they experience significant pain if they were diagnosed with CC and that they would be embarrassed to wear a colostomy bag. Some were worried about causing stress and extra burden to family members. One woman summarized the downhill trajectory with colon cancer and family and spiritual implications:

Well, I think there is depression just like they lost life. Hibernate. Grow recluse. Behave bitterly with family members. Refuse to eat. Lose weight, just go downhill. Those things can happen. And life will become shorter with those things. Or they can try to work to become better, work with their doctor, and work with the Lord and have some quality of life until the cancer would take over completely… If it were me? I think I wouldn’t live long. I don’t worry because I wouldn’t want to be a burden on my family. I think that they would have a hard time to live financially and take care of problems at home.

A few participants were disengaged about CC as they were more focused on their day-to-day life, only worrying if they had symptoms or were diagnosed with CC. Knowing about other people dying from CC made some participants worry. Additionally, having a family history and related symptoms (e.g., rectal bleeding) was a factor associated with CC worry.

Emotional Representation of CC Screening

Feelings associated with CC screening included embarrassment, discomfort at being “poked” or “prodded”, powerlessness, avoidance, worry and even disgust: “Ick! If they could just find another way to do it! It’s just nasty.” In terms of social factors, some specifically noted that they were not shy about exposure during exams; one participant even observed a male family member having a colonoscopy. Many participants thought that CC screening is a socially awkward procedure, and others reported negative feelings about screening from friends, “my boss told me you don’t want to get it done ‘cause it hurts, the way they have to stick something up your rectum and check it out.” Some noted that they would only get a colonoscopy of they had symptoms suggestive of CC, at which point it would be diagnostic. Part of the avoidance was not liking to go to the doctor in general. Some even thought that when screening results show some concerns, there would not be much to do for cancer patients; another indicated that she would not want to know if anything was wrong. Further, expense to screen and access was discussed as a barrier.

Discussion

The primary purpose of this mixed methods study was to investigate the association among a range of cultural, demographic, and psychological factors associated with colorectal cancer worry in rural Appalachian women. To begin, approximately half indicated that they experienced colon cancer worry. Other emotional factors were identified in both quantitative and qualitative samples, which played a role in overall negative affect. In our quantitative study, we utilized the Profile of Mood States, and ultimately, although fatigue, anxiety, and confusion were associated with worry, only anxiety remained in our larger model. Thus, colon cancer worry appears to be associated with a more general measure of well-being. Our qualitative data expanded these results and indicated that fear and worry about getting cancer were present, and that participants expected to experience depression and shock if diagnosed with cancer. The downward trajectory described by one participant was consistent with the belief that cancer meant death, identified in other minority populations (e.g., [32]).

One common source of worry was having to wear a colostomy bag if diagnosed with cancer and the potential social embarrassment associated with it. Along with the negative associations some made with colon cancer and its treatment, cancer screening was considered an unpleasant procedure. Some participants identified colon cancer screening as a socially inconvenient procedure and believed that embarrassment was a barrier to adhering to screening guidelines. This ‘yuck’ factor has been identified in other populations, as well [33]. Several participants described discomfort with having areas of their body exposed, but several participants noted that they were not at all uncomfortable with the exposure associated with colon cancer screening and had first-hand experience. Along with worry about discomfort and pain associated with colon cancer, some noted concerns about pain from the procedure. Our previous studies noted concern about pain as a key barrier for screening among Appalachian physicians in their patient population [34].

Access to care and financial resources for screening were identified as important factors in cancer worry. Interestingly, those reporting easy or difficult access to care had greater worry than those who indicated that they did not know or that it was neither easy nor difficult. This may be a proxy for whether someone had tried to have colon cancer screening (a measure which did not appear to be significantly related to cancer worry in our quantitative data, perhaps due to small sample size) or had witnessed another person who attempted to have screening. It may also reflect the range of cancer screening options, with Hemocult or Fecal Occult Blood Test being easily performed in a physician’s office and a colonoscopy being more difficult to arrange. In addition, this may reflect the medically-under-served, economically-challenged Appalachian population, which has considerable barriers to accessing health care [6]. As an addendum, one participant noted that she would be worried about the social and financial well-being of her family if she were diagnosed with cancer, and she would choose a more rapid demise to ease their burden. This not only reflects the importance of the family in Appalachian culture [35], but also the caregiving burden of women in the larger American society [36]. Although our qualitative data appears consistent with other findings of fatalism in the Appalachian culture (e.g., [37]), our larger quantitative data did not indicate that the validated fatalism scale was associated with worry. Rather, such decision-making may reflect a rational choice in response to financial and social barriers to cancer care [38].

Consistent with previous studies, women who thought they were more susceptible (absolute perceived risk) to colon cancer were more likely to exhibit colon cancer worry [39]. The SRM supports a close relationship between worry and perceived risk, as well as their potential role in predicting health behavior like colon screening [40]. This finding is further supported by the relationship of more education to worry, perhaps indicating that knowledge is a critical factor. Some in our qualitative analysis indicated that they never thought about colon cancer, did not have any feelings about it, or would not want to know if they had colon cancer. This, in turn, appeared to be reflected in their lack of desire to have colon cancer screening. Rather than colon cancer, they had many other concerns that took precedence over worry about colon cancer or screening. Many women did not want to screen for cancer but preferred to wait until symptoms appeared, at which point the testing would be diagnostic, rather than screening. This would mean that individuals would present with later stage disease, consistent with the elevated rate of mortality seen in Appalachia [3, 4]. Using symptoms as a prompt to take health action is consistent with the “common sense” understanding of illness in the SRM [15], and interventions should focus on the need for screening before symptoms present.

Strengths and limitations should be noted. Because the quantitative data was collected as part of a larger study investigating cervical cancer and colon cancer in women, the results are likely not generalizable to men, and additional studies are needed exploring cancer worry in men from Appalachian communities. Additionally, participants were recruited from Appalachian Ohio, so the results may not be representative of all Appalachia. Furthermore, the cross-sectional nature of this study may limit inferring any causality between the predictor variables and colon cancer worry. In spite of these limitations, the quantitative and qualitative components of this paper filled a gap in research pertaining to the feelings associated with colon cancer and screening, and methodological triangulation helped to further interpret findings.

Conclusion

Our qualitative analysis revealed a variety of emotions surrounding colon cancer and screening, and how the social context, particularly the family, is critical in understanding this worry. Additionally, we learned from the quantitative portion that colon cancer worry was associated with key variables defined by the SRM but less with cultural factors often cited as being important in Appalachia (e.g., religiosity; fatalism). The findings provided important clues to understanding the factors that predict colon cancer worry in a rural Appalachian population, as well as those that might be relevant to other populations, and shed light on how worry may contribute to cancer screening and overall well-being. Future research is needed to evaluate the health, humanistic, and financial burden of colon cancer worry among this population, and to identify the needs for improving colon cancer screening rates among those who are eligible to screen. We expect that the results will aid in designing more effective and targeted health interventions in the future that aim to eliminate health disparities related to colon cancer incidence and mortality in the Appalachian region.

Acknowledgments

We thank West Virginia Clinical and Translational Science Institute for statistical assistance it provided in preparing this manuscript.

Funding This research study was funded by the National Cancer Institute [Principal Investigator of Supplement to Promote Diversity in Health Research: Dr. Kimberly Kelly, Supplement PI. (5P50-CA105632-02) (Paskett, Center PI)].

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent Informed consent was obtained from all participants in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration, as revised in 2000.

References

- 1.Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. Jama. 2016;315(23):2564–2575. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.5989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures. 2017 Accessed May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson RJ, Ryerson AB, Singh SD, King JB. Cancer incidence in Appalachia, 2004–2011. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention: A Publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, Cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2016;25(2):250–258. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2017;67(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pollard K, Jacobsen LA. American community survey. Population Reference Bureau—Prepared for the Appalachian Regional Commission; 2014. The Appalachian region: A data overview from the 2008–2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Appalachian Regional Commission. The Appalachian Region. 2017 Retrieved May 1, 2017, from http://www.arc.gov.

- 7.Corrigan JM, Greiner AC, Adams K. 1st annual crossing the quality chasm summit: A focus on communities. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bardach SH, Schoenberg NE, Fleming ST, Hatcher J. Relationship between colorectal cancer screening adherence and knowledge among vulnerable rural residents of Appalachian Kentucky. Cancer Nursing. 2012;35(4):288–294. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31822e7859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Llanos AA, Pennell ML, Young GS, Tatum CM, Katz ML, Paskett ED. No association between colorectal cancer worry and screening uptake in Appalachian Ohio. Journal of Public Health. 2014;37(2):322–327. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdu031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelly KM, Schoenberg N, Wilson TD, Atkins E, Dickinson S, Paskett E. Cervical cancer worry and screening among Appalachian women. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2014;36(2):79–92. doi: 10.1007/s10935-014-0379-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baugh CS, Myers MF, Hendryx MS, et al. Appalachian health and well-being. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hay J, Buckley TR, Ostroff JS. The role of cancer worry in cancer screening: A theoretical and empirical review of the literature. Psycho-Oncology. 2005;14(7):517–534. doi: 10.1002/pon.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vrinten C, Marlow L, Waller J. What is it about cancer that worries people? A population-based survey of adults in England. European Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2016;42(11):S239. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cameron LD, Leventhal H. The self-regulation of health and illness behaviour. New York: Routledge; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leventhal H, Benyamini Y, Brownlee S, et al. Illness representations: Theoretical foundations. Perceptions of health and illness. 1997;2:19–46. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drew EM, Schoenberg NE. Deconstructing fatalism: Ethnographic perspectives on women’s decision making about cancer prevention and treatment. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2011;25(2):164–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1387.2010.01136.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keeler EB, Sloss EM, Brook RH, Operskalski BH, Goldberg GA, Newhouse JP. Effects of cost sharing on physiological health, health practices, and worry. Health Services Research. 1987;22(3):279–306. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hay J, Coups E, Ford J. Predictors of perceived risk for colon cancer in a national probability sample in the United States. Journal of Health Communication. 2006;11(Suppl 1):71–92. doi: 10.1080/10810730600637376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Photiadis JD. Religion: A persistent institution in a changing Appalachia. Review of Religious Research. 1977;19(1):32–42. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Behringer B, Krishnan K. Understanding the role of religion in cancer care in Appalachia. Southern Medical Journal. 2011;104(4):295–296. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3182084108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hesse-Biber SN. Mixed methods research: Merging theory with practice. New York: Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Powe BD. Fatalism among elderly African Americans. Effects on colorectal cancer screening. Cancer Nursing. 1995;18(5):385–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brenes GA, Paskett ED. Predictors of stage of adoption for colorectal cancer screening. Preventive Medicine. 2000;31(4):410–416. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lerman C, Kash K, Stefanek M. Younger women at increased risk for breast cancer: perceived risk, psychological well-being, and surveillance behavior. Journal of the National Cancer Institute Monographs. 1993;16:171–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tully PJ, Cosh SM, Baune BT. A review of the affects of worry and generalized anxiety disorder upon cardiovascular health and coronary heart disease. Psychology, Health and Medicine. 2013;18(6):627–644. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2012.749355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Worthington EL, Wade NG, Hight TL, et al. The religious commitment inventory–10: Development, refinement, and validation of a brief scale for research and counseling. American Psychological Association. 2003;50(1):84–96. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shacham S. A shortened version of the profile of mood states. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1983;47(3):305–306. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4703_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care. 1992;30(6):473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joseph DA, King JB, Miller JW, Richardson LC, Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC) Prevalence of colorectal cancer screening among adults-behavioral risk factor surveillance system, United States, 2010. MMWR Supplements. 2012;61(2):51–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borkan J. Immersion/crystallization. In: Crabtree B, Miller W, editors. Doing qualitative research. 2nd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1999. pp. 179–194. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller WL, Crabtree BF. Clinical research. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2000. pp. 366–378. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flórez KR, Aguirre AN, Viladrich A, et al. Fatalism or destiny? A qualitative study and interpretative framework for Dominican women’s breast cancer beliefs. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2009;11:291. doi: 10.1007/s10903-008-9118-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reynolds LM, Consedine NS, Pizarro DA, Bissett IP. Disgust and behavioral avoidance in colorectal cancer screening and treatment: A systematic review and research agenda. Cancer Nursing. 2013;36(2):122–130. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31826a4b1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kelly KM, Phillips CM, Jenkins C, Norling G, White C, Jenkins T, Armstrong D, Petrik J, Steinkuhl A, Washington R, Dignan M. Physician and staff perceptions of barriers to colorectal cancer screening in Appalachian Kentucky. Cancer Control: Journal of the Moffitt Cancer Center. 2007;14(2):167–175. doi: 10.1177/107327480701400210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manoogian MM, Jurich J, Sano Y, Ko J. “My kids are more important than money” Parenting expectations and commitment among Appalachian low-income mothers. Journal of Family Issues. 2015;36(3):326–350. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adelman RD, Tmanova LL, Delgado D, Dion S, Lachs MS. Caregiver burden: A clinical review. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2014;311(10):1052–1060. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vanderpool RC, Dressler EVM, Stradtman LR, Crosby RA. Fatalistic beliefs and completion of the HPV vaccination series among a sample of young Appalachian Kentucky women. The Journal of Rural Health. 2015;31(2):199–205. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harris G. Sowing seeds in the mountains: community-based coalitions for cancer prevention and control. Appalachia Leadership Initiative on Cancer, Cancer Control Sciences Program; 1994. (No. 94). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zajac LE, Klein WM, McCaul KD. Absolute and comparative risk perceptions as predictors of cancer worry: Moderating effects of gender and psychological distress. Journal of Health Communication. 2006;11(Suppl 1):37–49. doi: 10.1080/10810730600637301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leventhal H, Kelly K, Leventhal EA. Population risk, actual risk, perceived risk, and cancer control: A discussion. Journal of the National Cancer Institute Monographs. 1999;25:81–85. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a024214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]