Abstract

Background/Aim: Physical activities are an essential part of patients’ rehabilitation in oncology. For cancer patients special sport groups for rehabilitation exist and are reimbursed by the statutory health system. The aim of our study was to evaluate patients’ knowledge and acceptance of these offers and their actual sportive engagement. Patients and Methods: We used a standardized questionnaire which was distributed in medical oncology and ENT oncology practice. Results: From 200 questionnaires, we got 155 (76%) answers (83 females, 71 males, mean age was 64.8±12.0 years. A total of 80 patients had current cancer therapy. Sportive activity was decreasing from 71% before cancer, to 50% during therapy, to 40% after anticancer treatment. Only 24% of participants were informed about local offers for cancer patients. The 38% of our patients would like to become more active. Gender, former sportive experience, favourite disciplines, and the type of cancer are factors with a high impact on patient’s affinity to physical exercise. Conclusion: The presented screening tool offers first and fast information about the patient’s affinity to sports and helps the oncologist to offer patients individualized training concepts.

Keywords: Sports, physical activity, screening, cancer

Co-morbidities have a high impact on the progression of cancer disease. Recently, Göllnitz et al. have published data about the independent risk factor co-diagnosis. Poorer prognosis was observed when more co-morbidity was registered (1). On the other side, co-morbidity is influenced by its own risk factors. Alcohol and nicotine consumption are well known as well as low physical activity of patients.

The concept of physical exercises is well established as one of the basic components of early rehabilitation for cancer patients (2). This includes the recovering in daily life activities as walking, self-care and integration in the familiar system as well as special training programs for improving physical limitations due to disease or its therapy (3-7).

In spite of these highly positive results, adherence of patients to exercise programs is rather low. Patients are well motivated in clinical and out-clinical setting during the anti-cancer treatment, yet, only few offers exist for this group. In Germany, patients are offered a three-week phase of rehabilitation in specialized clinics. In these clinics, all patients take part in some training. During acute therapy and stationary rehabilitation, they are in close and continuous contact with the therapists, doctors and the medical staff, who may recommend physical activities and motivate the patients. One reason for low adherence after these well-organized programs might be that patients have to look for and organize training by themselves later on. Moreover, with lack of continuous recall, they have to motivate themselves. Last but not least, survived patients want to return to normal life and may return to former lifestyle patterns.

The aim of our pilot study was to develop a short standardized questionnaire that may be used as screening tool in the aftercare setting to learn about the physical activities of cancer patients. The questionnaire should be self-explanatory for the reporting patient, short and informative for the physician in charge.

Patients and Methods

Questionnaire. Experts of the working group PRIO (Prevention and Integrative Oncology within the German Cancer Society) collected and defined the relevant items of the questionnaire. A first version was drafted and was tested in 10 patients. As the questionnaire was easy to understand and could be filled in without help of a nurse, this pilot version was used.

In order to assess understandability, all answers that were not consistent with other answers form the same patients were marked with “99” in the MS Excel table to get information about the difficulty of the patients with the screening tool at all and the different questions in detail.

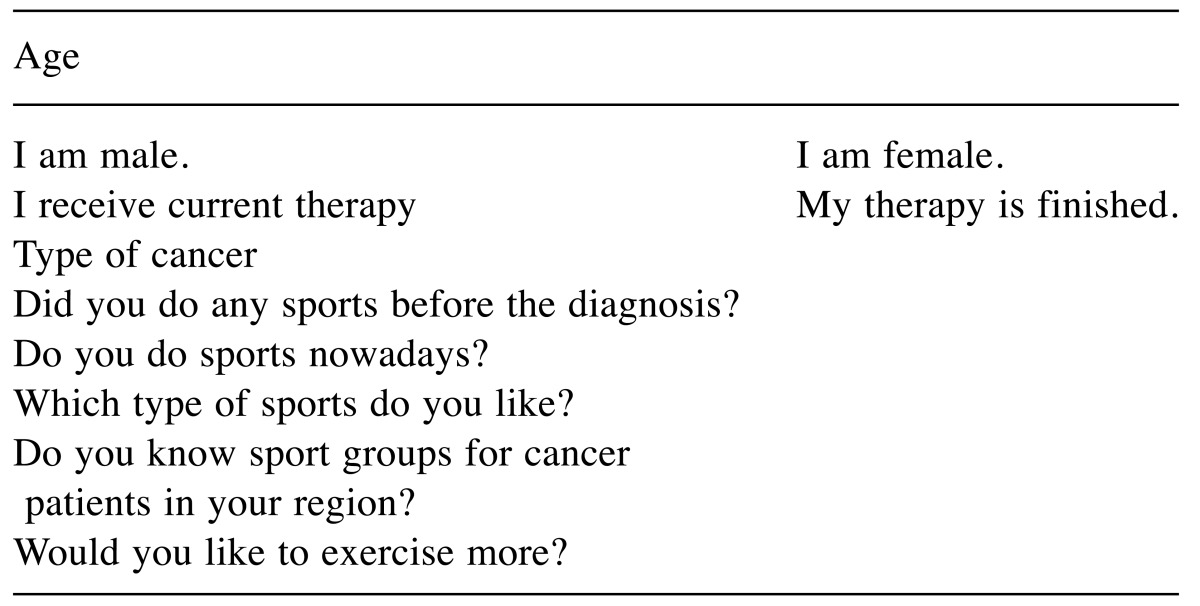

The original version is available as online supplement (Table I). It consists of three main parts. The first comprises demographic data (age, gender, type of cancer, actual therapy or aftercare). Secondly, we asked for physical activity/sports in the past and in the current situation and the favorite discipline). The third part includes two questions about knowledge of regional offers and the desire for (any or more) physical activities. All questions were open questions. Time needed for the questionnaire was less than 5 minutes.

Table I. Questionnaire on sport for patients with cancer.

Patients. Afterwards the pilot test, the questionnaire was given to a first cohort of 100 consecutive patients in spring 2016. We chose two institutions (a medical oncology department and an ENT oncology department) in order to include patients with very different entities. Inclusion criteria were histologically proven malignancy, patients during and after therapy, ability to understand the questions and to write the answers and willingness to participate. After analysis of the interim data (8) another cohort of 100 patients was included from the same institutions. The patients were asked to fill in the questionnaire during their waiting time before a planned contact to the physician.

Ethical vote. As the screening questionnaire was anonymous, due to the regulations of the ethics review committee responsible no vote was necessary. All research was done in concordance with the actual version of declaration of Helsinki.

Statistics. Data from the questionnaire were transferred into a MS Excel table. Frequencies were computed and correlation was tested by Chi-square test with a p-value of 0.05.

Results

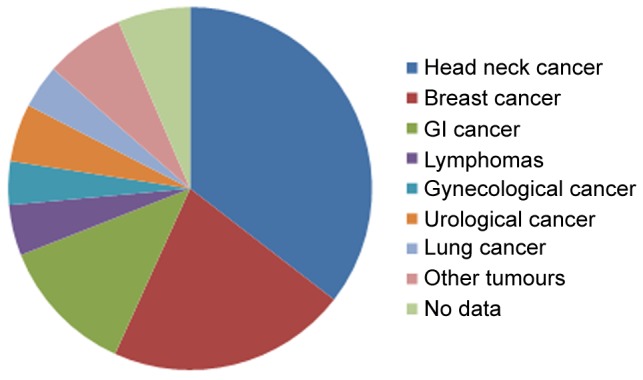

Demographic data and practicability of the questionnaire. Two hundred questionnaires were distributed, and 155 were returned. In total, we received 155/200 questionnaires (77.5%; 81% in 1st phase, 74% in 2nd phase). Accordingly, 155 patients (71 males, 83 females, 1 unknown) were included in the analysis. A total of 80 patients were still under ongoing anti-cancer treatment. 50 participants were interviewed during follow-up visit. 25 were not able to categorize themselves. The cancer diagnoses are demonstrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Tumor localisation.

In total, all questions were answered by more than 80% of the participants. two questions seem to be difficult for some patients. Twenty-five (12.5%) did not answer the question on current treatment versus follow-up. Nine participants did not answer the question on their knowledge regarding local sports offers. This answer might be interpreted as a "no". Thirteen patients did not answer whether they would like to become more active.

Physical activity. Seventy-one percent of our participants reported having been physically active before their cancer diagnosis. At the time of the study 45% reported active exercising behavior. Regional offers were known to 24% of our patients only. Thirty-eight percent of all participants would like to become more active.

Disciplines and types of physical activities. Seventy participants (45.2%) favored endurance disciplines as swimming, jogging, walking or cycling. Twenty patients (12.9%) preferred gymnastics, mind-body-exercises including yoga or thai chi sessions. Thirty-one patients (20.0%) took part in ball sports within a team (soccer, handball, volleyball). Other activities were resistance training, tennis and sport shooting, dancing and riding.

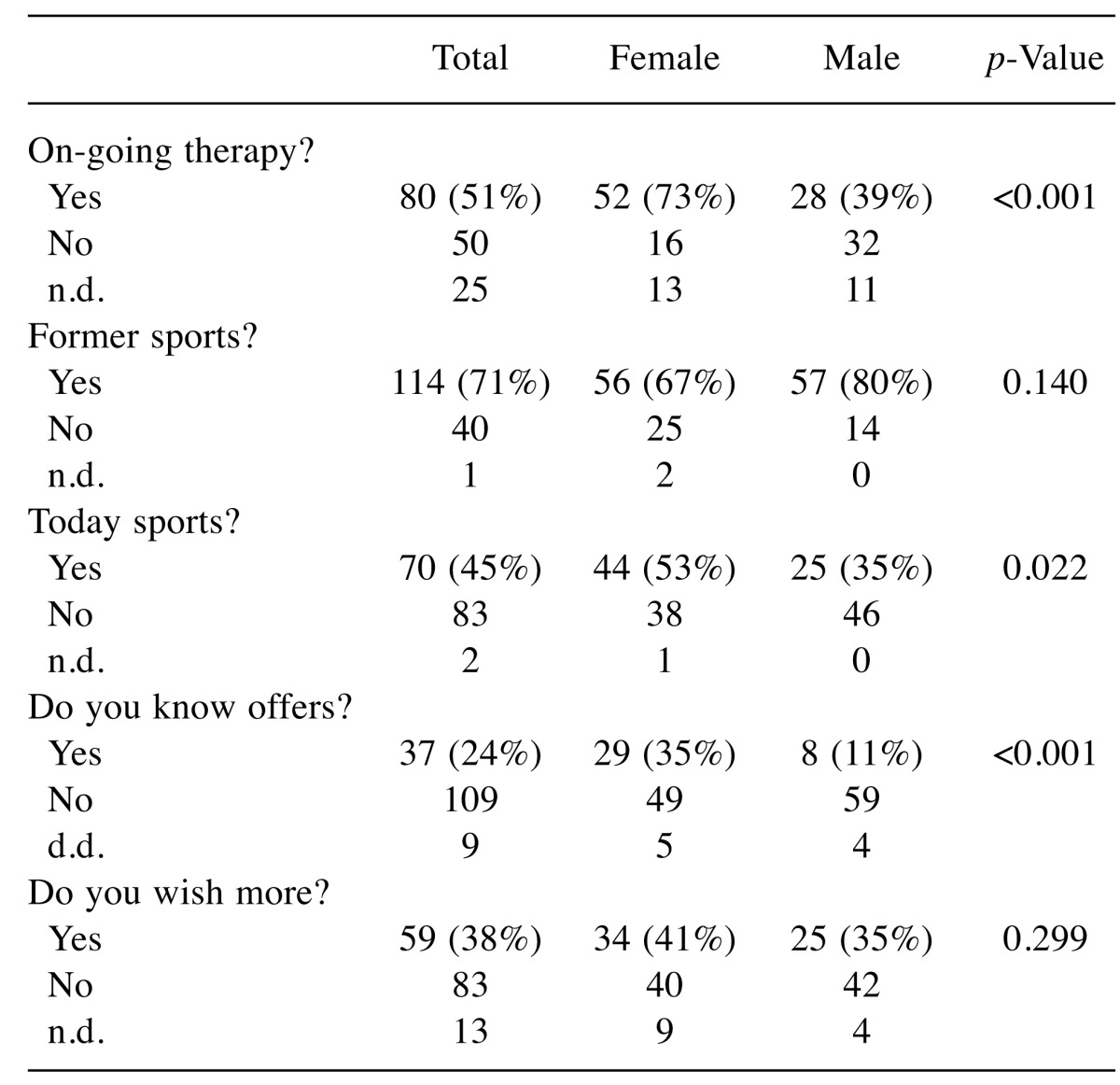

Influencing factors for physical activities. Gender (Table II): While male participants more often reported having been active in the past (p=0.140), women were more often taking part in sports and other physical activity during and after therapy (p=0.022). Male patients had less knowledge about local possibilities (p<0.001). With respect to the wish to become more active, there was no difference between male and female participants.

Table II. Affinity to sports depending to gender.

n.d.: No data

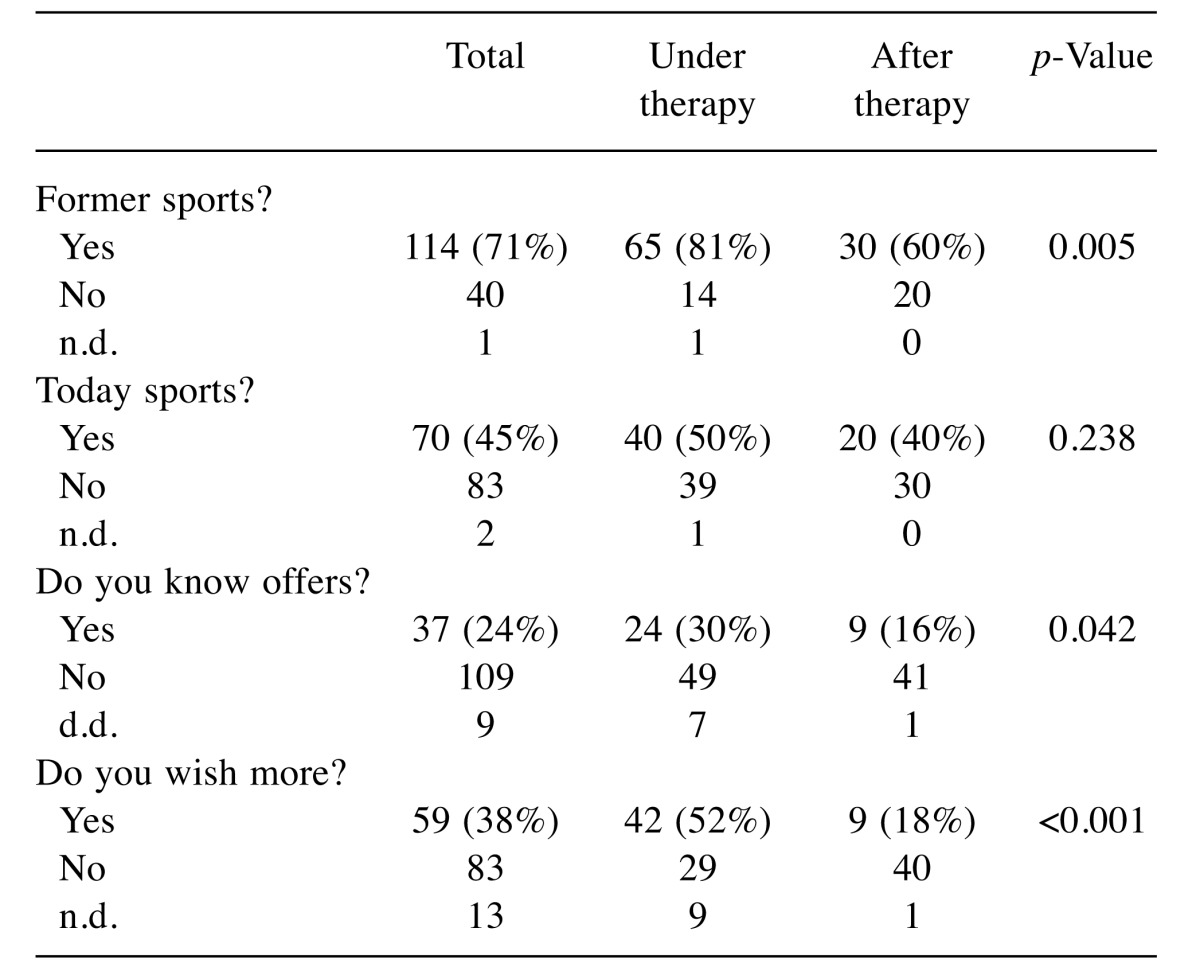

Status of therapy (Table III): While 50% of the participants reported being active during therapy, this number dropped to 40% during aftercare (not significant). Yet, knowledge on regional offers significantly differed. While 30% reported being familiar with offers during therapy, only 16% did so later on (p=0.042). Moreover, the actual wish to become more active dropped from 52% to 18% (p<0.001).

Table III. Time of interview and sporting exercises.

n.d.: No data

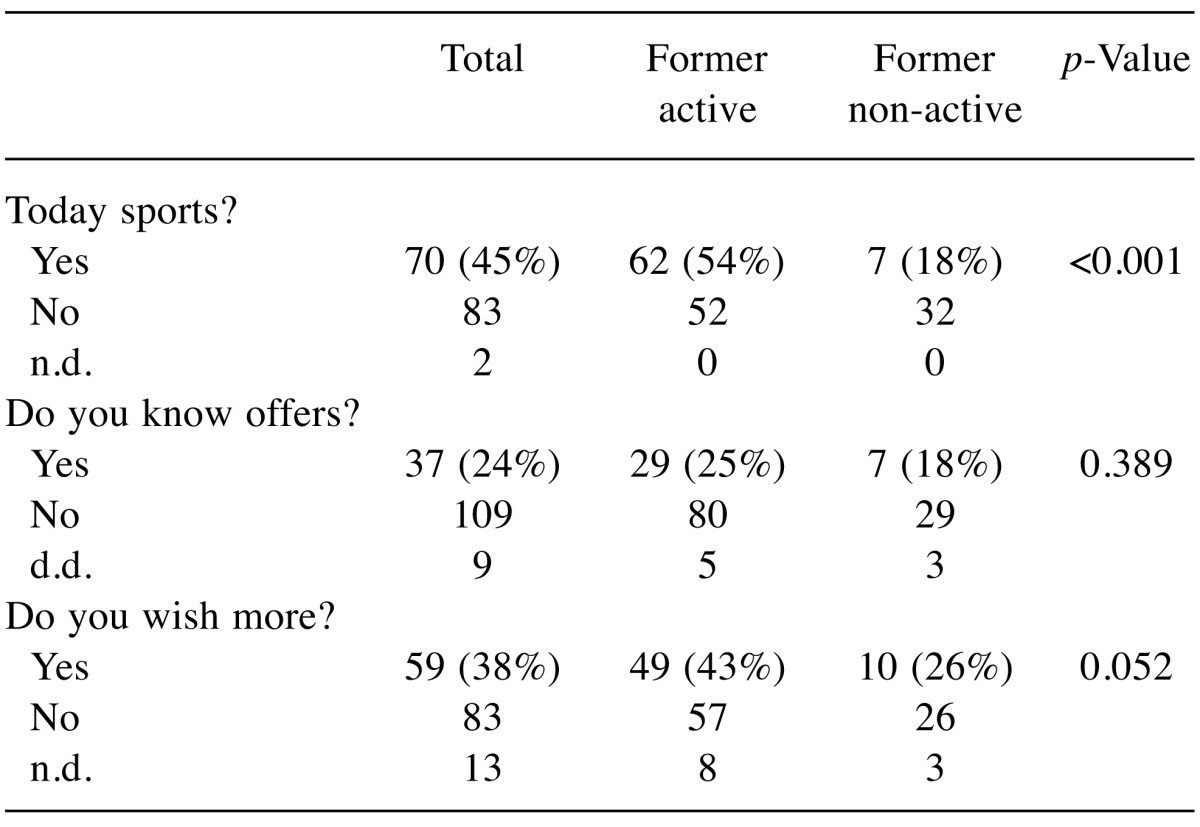

Sport experience (Table IV): Earlier sportsmen were more active during and after therapy (p<0.001). Yet, they have no advantage regarding their knowledge of local offers. There is a trend to a higher desire for future sports in contrast to former non-sportive persons (p=0.052).

Table IV. Former sportive experience and actual physical activity.

n.d.: No data

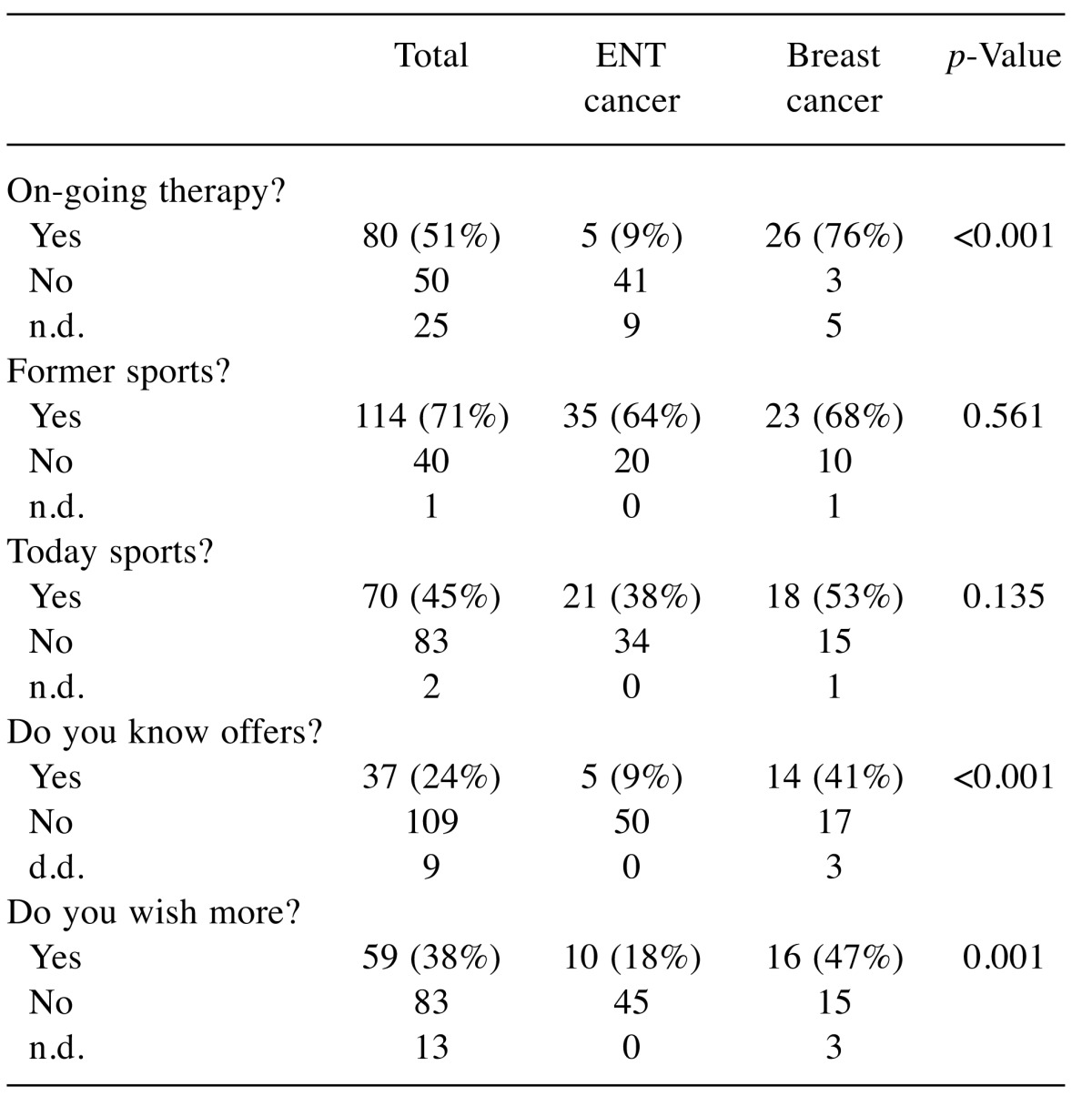

Tumor localization (Table V): With respect to the two largest entities included in our study, we have analyzed the data of head neck cancer patients and breast cancer patients. There was no significant difference with respect to affinity to sports in former times and physical activity at the time of study.ENT cancer patients have significant less information about local offers (p<0.001) and are less interested in increasing physical activity (p=0.001).

Table V. Tumor localization and sportive behavior (examples: head neck cancer, breast cancer).

n.d.: No data

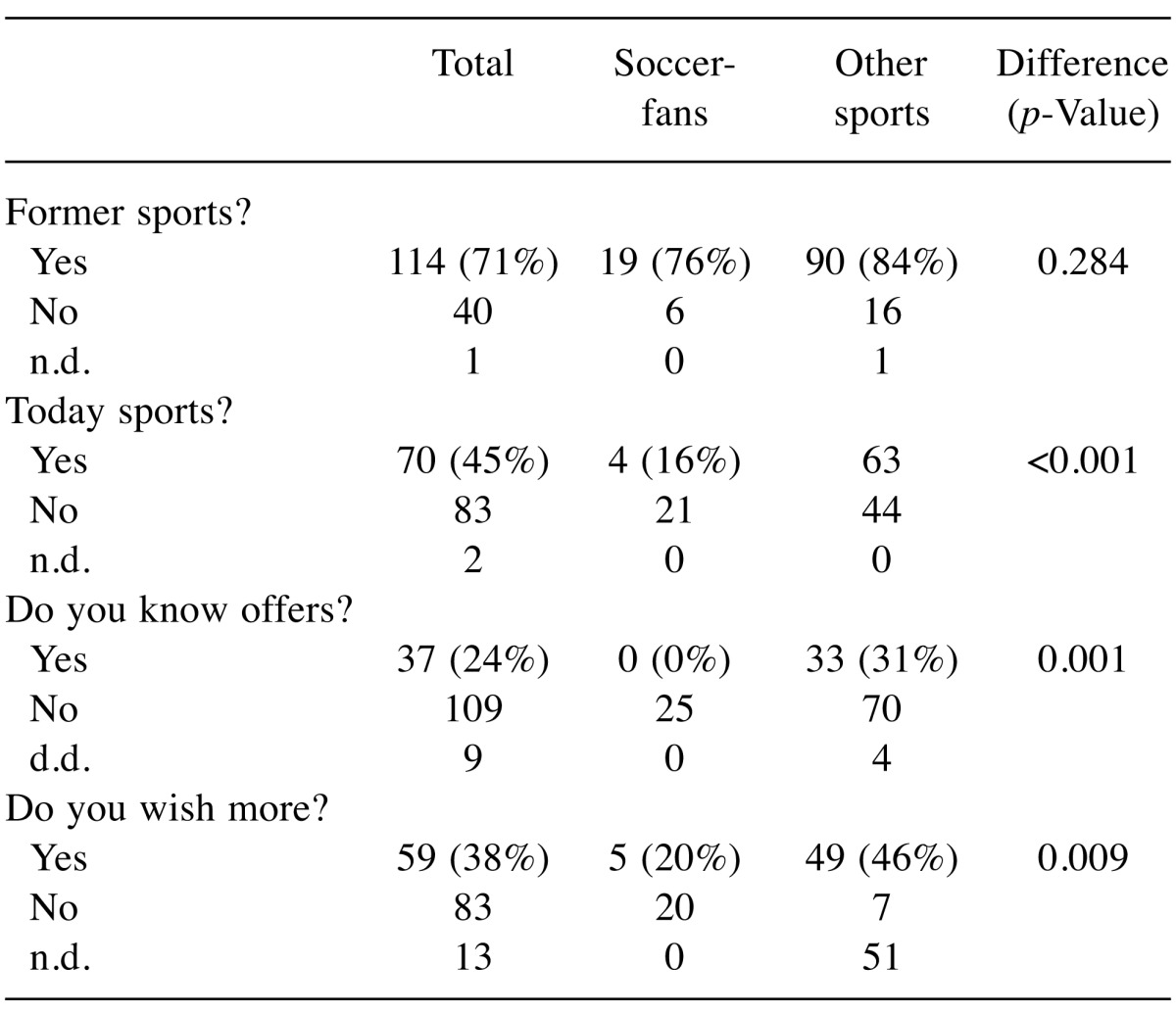

Favorite discipline (Table VI): As soccer is the most known type of sport in Germany, we looked for associations of former active soccer playing and current activities and interest. No-soccer fans are more active. The favorite “soccer” is associated with less own physical activity in our study population (p<0.001), less information on offers (p=0.001) and lower wishes to become more active (p=0.009).

Table VI. Soccer fans and their own activity.

n.d.: No data

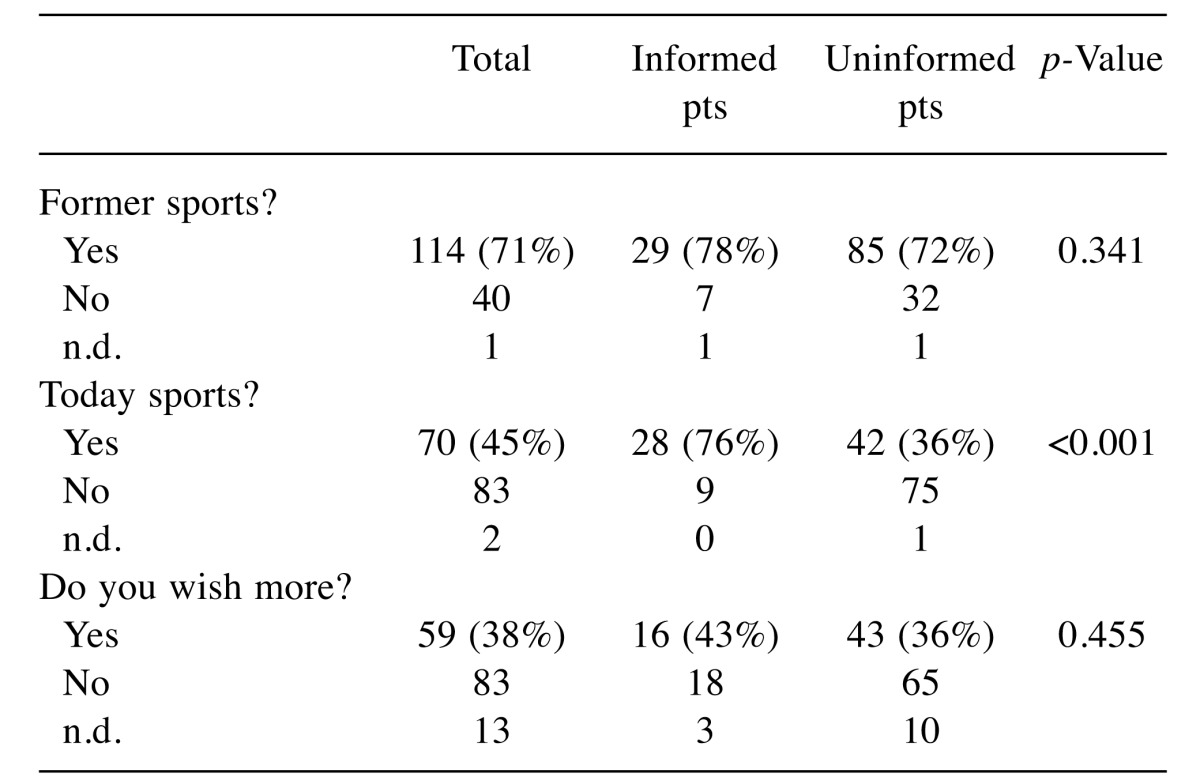

Information status (Table VII): Patients who are better informed on offers significantly more often are active (p<0.001). Yet, both groups are interested in future sport activities (p=0.455).

Table VII. Information status and active behavior.

n.d.: No data

Discussion

For cancer patients, lifestyle in general and especially physical activities are important with respect to reduction of side effects and improvement of quality of life during and after therapy. Moreover, physical activity has a strong positive impact on prognosis (9-11).

The questionnaire we developed is suitable for a quick screening of cancer patients during and after therapy with respect to their actual current activity, their motivation and knowledge of special offers for cancer patients. The questionnaire can be filled in few minutes by the patient while waiting for the appointment with the physician. The screening tool is well accepted by the patients. Its usage gives a standardized orientation about the physical activities already in the waiting-zone before the consultation room. Due to its shortness and clarity, the physician can easily assess the situation and include recommendations with respect to physical activities which fit the individual patient’s needs.

Only 45 % of our cancer patients reported taking part in physical exercises. Less than a quarter knows the possibilities offered in their region. The physical activity is decreasing during the anti-cancer therapy. 71% of our participants were active in former times. During the therapy, this rate decreases to nearly 50% and after the end of treatment 40% remained active. Former sportive persons are easier to motivate for sport as rehabilitation. Earlier sportsmen have a higher interest in the topic and wish to improve their physical abilities.

This trajectory may be due to the increasing exhaustion of patients during treatment. Special offers from physiotherapy and more individualized group activities may be suitable to help these patients to adhere during treatment. In fact, this might also reduce an emerging problem of longer and more successful cancer therapies: fatigue, which is reported by many patients and for which no medical treatment offers consistent benefit.

Hilfiker and colleagues (12) have published a meta-analysis about physical activity and chronic fatigue in cancer patients. Individualized training during and after therapy with an optimized succession of training and relaxation are mandatory. Traditional endurance disciplines are easy to integrate into daily life and show effects after a few weeks of training. Interval and resistance exercises have been positively assessed in the last decades (13,14). Moreover, broad acceptance has developed for mind body concepts with elements of Thai Chi or Yoga. Positive results with respect to fatigue and other symptoms have been described (15,16). Yet, it has to be noticed that these Asian Movement concepts differ widely in their execution form more meditative to more power-oriented exercises. In comparison to physiotherapy, both concepts are equally effective. Moreover, Yoga only is effective during active therapy not in the aftercare (15).

Early integration of physical activities should be included in the supportive care in cancer patients. Successful early exercise programs should also raise patients’ motivation to start and continue exercising. Yet, some of the effects will be limited. Schmidt et al. have described a decreasing motivation in a randomized study with breast cancer patients (17) which is in accordance with our data. Decreasing willingness to exercise in aftercare may have diverse reasons. Ongoing fatigue may be one, ongoing side effects as fatigue but also neuropathy may turn exercising to an exhausting experience. Lack of adequate training groups with peers with the same diagnosis is another problem. Moreover, with successful rehabilitation, many patients nowadays return to work and may miss time for exercising especially if they also are engaged in family and social activities. More distance to the diagnosis and a less frightful perspective may also lower motivation at least in those who have no intrinsic inclination to physical activities.

While offering different groups for a broad range of cancer and treatment types will not be possible in most regions a diversification of regional sportive rehabilitation programs for patients with different diseases (for example cardiovascular, endocrine, etc.) seems more realistic. These programs might also include activities like dancing (18) or riding. Also, the combination of cognitive behavior training and physical exercises will offer new fields of rehabilitation. One access to the patients could be their high interest in complementary treatments. All 90% of breast cancer patients and 40 % of head neck cancer patients are interested in doing something additionally (19). In fact, physical activity in most cases is the best answer to the questions of these patients with best results and highest evidence as compared to many other types of complementary and alterantive medicine.

The type of diagnosis is not associated with the motivation to exercise and also head neck cancer patients which often are less privileged with respect to their socio-cultural setting may be sportive (20).

We have reported about the activities after laryngectomy. The patients have high limitations due to disease and therapy. Motivated patients were able to take part in specialized programs despite tracheostomy and larynx resection including aqua-therapy exercises (21,22). The development of this program has taken two decades and could be a prototype for other programs to improve the individual training possibilities for every cancer patient in specialized cancer care.

Physical exercises have to be integrated in comprehensive lifestyle programs including healthy nutrition, reduction of alcohol or nicotine consumption as well as drug abuse. These topics may well be addressed in the public starting at kindergardens, moving to schools and to education programs for adults. Increasing health literacy is mandatory to enable patients to better understand recommendations. Media, including mass media and social networks may help to reach the patients. Higher educated patients will take part in prevention or rehabilitation programs of sport and healthy nutrition. Patient’s advocacy groups could be a good bridge between the patient and the professional caregivers. Physicians as well as institutions as the German Cancer Society should enhance the competence of these groups and support their work in order to improve their acceptance among the professionals.

Furthermore, it is necessary to improve our own medical and nursing education. Sports and physical activity play a central role in recovery of our patients. Further research is necessary to develop concepts for different cancer settings. As the patient has his experiences, preferences and perspectives we as professionals may add well-defined concepts based on external evidence. The presented screening tool may be suitable to initiate the first talk between the physician and the patient on this important topic.

References

- 1.Göllnitz I, J Inhestern, TG Wendt, J Buentzel, D Esser, D Boeger, AH Mueller, JU Piesold, Schultze-Mosgau S, Eigendorff E, Schlattmann P, Guntinas-Lichius O. Role of comorbidity on outcome of head and neck cancer: A population-based study in Thuringia, Germany. Cancer Med. 2016;5:3260–3271. doi: 10.1002/cam4.882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leensen MCJ, Groeneveld IF, Rejda T, Groenenboom P, van Berkel S, Brandon T, de Boer AGEM, Frings-Dresen MHW. Feasibility of a multidisciplinary intervention to help cancer patients return to work. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2017 doi: 10.1111/ecc.12690. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12690. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baumann FT, Bloch W, Weissen A, Brockhaus M, Beulertz J, Zimmer P, Streckmann F, Zopf EM. Physical activity in breast cancer patients during medical treatment and in the aftercare – a review. Breast Care. 2013;8:330–334. doi: 10.1159/000356172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayes SC1, Rye S, Disipio T, Yates P, Bashford J, Pyke C, Saunders C, Battistutta D, Eakin E. Exercise for health: a randomized, controlled trial evaluating the impact of a pragmatic, translational exercise intervention on the quality of life, function and treatment-related side-effects following breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;137:175–186. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2331-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Markes M, Brockow T, Resch KL. Exercise for women receiving adjuvant therapy for breast cancer. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006;4:1–39. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005001.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmidt T, Weisser B, Jonat W, Baumann FT, Mundhenke C. Gentle strength training in rehabilitation of breast cancer patients compared to conventional therapy. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:3229–3233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmitz KH, Courneya K, Matthews C, Demark-Wahnefried W, Galvão DA, Pinto B, Irwin M, Wolin K, Segal R, Lucia A, Schneider C, Gruenigen von V, Schwartz A. American College of Sports Medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;7:1409–1426. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181e0c112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Büntzel J, Kubin T, Rudolph Y, Derlien S, Kusterer L, Hübner J, Schmidt T. Sport als Rehabilitationsmaßnahme. Was denken unsere Tumorpatienten. Forum. 2016;31:130–132. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lahart IM, Metsios GS, Nevill AM, Carmichael AR. Physical activity, risk of death and recurrence in breast cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Acta Oncologica. 2015;54:635–654. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2014.998275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hvid T, Lindegaard B, Winding K, Iversen P, Brasso K, Solomon TPJ, Pedersen BK, Hojman P. Effect of a 2-year home-based endurance training intervention on physiological function and PSA doubling time in prostate cancer patients. Cancer Causes and Control. 2016;27:165–174. doi: 10.1007/s10552-015-0694-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Courneya KS, Friedenreich CM, Franco-Villalobos C, Crawford JJ, Chua N, Basi S, Norris MK, Reiman T. Effects of supervised exercise on progression-free survival in lymphoma patients: an exploratory follow-up of the HELP Trial. Cancer Causes Control. 2015;26:269–276. doi: 10.1007/s10552-014-0508-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hilfiker R, Meichtry A, Eicher M, Nilsson BL, RH Verra, Taeymans J. Exercise and other non-pharmaceutical interventions for cancer-related fatigue in patients during or after cancer treatment: a systematic review incorporating an indirectcomparisons meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2017 doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096422. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096422. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schulz SV, Laszlo R, Otto S, Prokopchuk D, Schumann U, Ebner F, Huober J, Steinacker JM. Feasibility and effects of a combined adjuvant high-intensity interval/strength training in breast cancer patients: a single-center pilot study. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;21:1–8. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2017.1300688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheema B, Gaul CA, Lane K, Fiatarine Singh MA. Progressive resistance training in breast cancer: a systematic review of clinical trails. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;109:9–12. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9638-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cramer H, Lange S, Klose P, Paul A, Dobos G. Yoga for breast cancer patients and survivors: a systematic review andmeta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:412. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pan Y, Yang K, Wang Y, Zhang L, Liang H. Could yoga practice improve treatment-related side effects and quality of life for women with breast cancer? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2015;13(2):e79–e95. doi: 10.1111/ajco.12329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmidt ME, Wiskemann J, Ulrich CM, Schneeweiss A, Steindorf K. Self-reported physical activity behavior of breast cancer survivors during and after adjuvant therapy: 12 months follow-up of two randomized exercise intervention trials. Acta Oncol. 2017;56:618–627. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2016.1275776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pisu M, Demark-Wahnefried W, Kenzik KM, Oster RA, Lin CP, Manne S, Alvarez R, Martin MY. A dance intervention for cancer survivors and their partners (RHYTHM) J Cancer Surviv. 2017;11:350–359. doi: 10.1007/s11764-016-0593-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Micke O, Bruns F, Glatzel M, Schönekaes K, Micke P, Mücke R, Büntzel J. Predictive factors for the use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in radiation oncology. Eur J Integr Med. 2009;1:19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Büntzel J, Büntzel H, Mücke R, Besser A, Micke O. Sport in the rehabilitation of patients after total laryngectomy. Anticancer Res. 2016;36:3191–3194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karamzadeh AM, Armstrong WB. Aquatic activities after total laryngectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;125:528–632. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2001.119323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crevenna R, Schneider B, Mittermaier C, Kellani M, Zöch C, Nuhr M, Wolzt M, Quittan M, Biegenzahn W, Fialka-Moser V. Implementation of the Vienna hydrotherapy group for laryngectomees – a pilot study. Supp Care Cancer. 2003;11:735–738. doi: 10.1007/s00520-003-0516-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]