Abstract

Purpose

To extend the pH detection range of iopamidol-based ratiometric chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) MRI at sub-high magnetic field and establish quantitative renal pH MRI.

Methods

CEST imaging was performed on iopamidol phantoms with pH of 5.5–8.0 and in vivo on rat kidneys (N = 5) during iopamidol administration at a 4.7 Tesla. Iopamidol CEST effects were described using a multi-pool Lorentzian model. A generalized ratiometric analysis was conducted by ratioing resolved iopamidol CEST effects at 4.3 and 5.5 ppm obtained under 1.0 and 2.0 μT, respectively. The pH detection range was established for both the standard ratiometric analysis and the proposed resolved approach. Renal pH was mapped in vivo with regional pH assessed by one-way ANOVA.

Results

Good fitting performance was observed in multi-pool Lorentzian resolving of CEST effects (R2s > 0.99). The proposed approach extends the in vitro pH detection range to 5.5–7.5 at 4.7 Tesla. In vivo renal pH was measured to be 7.0±0.1, 6.8±0.1 and 6.5±0.2 for cortex, medulla and calyx, respectively (P<0.05).

Conclusion

The proposed ratiometric approach extended the iopamidol pH detection range, enabled renal pH mapping in vivo, promising for pH imaging studies at sub-high or low fields with potential clinical applicability.

Keywords: Chemical exchange saturation transfer, ratiometric imaging, kidney, pH, iopamidol

INTRODUCTION

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) serves as a versatile technique to assess kidney functionality. As kidney plays a vital role in balancing body acid/base homeostasis, pH MRI is promising to identify renal dysfunction, diagnose regional kidney injury before symptom onset and ultimately, guide treatment prior to irreversible damage (1–3). However, standard pH measurement techniques, including lactate, phosphorous and hyperpolarized 13C magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) are limited for routine renal imaging due to their relatively coarse spatiotemporal resolution or requirement of polarization devices (4–8). Gadolinium-based pH imaging provides novel insight of renal physiology and its disruption, yet it requires independent determination of local contrast agent concentration (9, 10). Although this can be achieved by administering a second pH-insensitive agent with identical tissue pharmacokinetics, the repeated injection of contrast agents makes it somewhat cumbersome (1, 11). The development of pH-sensitive PET/MRI hybrid contrast agent elegantly harnesses the pH sensitivity, MRI resolution and PET quantification of contrast agent concentration for pH mapping. However, this approach requires simultaneous PET and MRI acquisition, which is not widely available yet (12).

Iopamidol, an FDA-approved computed tomography contrast agent, has two distinct MR visible chemical exchangeable groups of different pH-dependent exchange rate. The development of ratiometric chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) MRI enables concentration-independent pH imaging (13–15). Its pH detection range has been shown to be 5.5–7.4 at 7 Tesla (T) and 6.0–7.6 at 14 T (16, 17). Additional CEST agents have been investigated for pH imaging, including iopromide (18), imidazoles (19), and paramagnetic CEST (paraCEST) agents (20). Recently, radio-frequency (RF) power-based ratiometric pH MRI has been proposed that enables ratiometric MRI using iobitridol, a CEST agent with a single exchangeable group, for renal pH imaging (21). It is worthwhile to point out that most renal pH MRI studies thus far have been demonstrated at high fields (≥ 7 Tesla). When translated to low/sub-high field, the dynamic pH range has been substantially reduced due to overlapped CEST effects and more prominent concomitant saturation transfer effects (16, 22). As renal pH spans a relatively broad range, (1, 2, 16, 21), our study aimed to devise a new means of ratiometric CEST MRI to enable renal pH imaging at 4.7 T as a pertinent step forward toward clinical application.

METHODS

MRI studies

The prospective study was conducted on a 4.7 T small-bore MRI scanner (Bruker Biospec, Billerica, MA). We used iopamidol phosphate buffered solution (PBS) phantom for pH calibration (16). Briefly, pH of 40 mM iopamidol PBS solution was titrated to 5.5, 6.0, 6.5, 7.0, 7.5 and 8.0, and imaged under 37°C. We used single-shot spin-echo (SE) echo planar imaging (EPI) with a field of view (FOV) of 52×52 mm2, image matrix = 96×96 and slice thickness = 5 mm. We collected two Z-spectra for RF power (B1) levels of 1.0 and 2.0 μT (frequency offsets between ±7 ppm with intervals of 0.25 ppm, repetition time (TR)/saturation time (TS)/echo time (TE)=10,000/5,000/48 ms). Water saturation shift referencing (WASSR) map was collected with B1=0.3 μT (frequency offsets between ±0.125 ppm with intervals of 0.025 ppm, TR/TS=2,000/1,000 ms).

In vivo experiments have been approved by the local Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Briefly, adult male Wistar rats (N = 5, 292± 28g) were initially anesthetized with 5% isoflurane. Endotracheal intubation was performed after the animal was sufficiently anesthetized. The animals were mechanically ventilated at a rate of 60±2 bpm with 1.5–2% isoflurane in room-temperature air using a ventilator (Kent Scientific, Torrington, CT). Their body temperature was maintained at 37°C by a circulating warm water jacket positioned around the torso. A single slice image along the long axis of the left kidney was imaged with CEST MRI during iopamidol administration (FOV= 20×20 mm2, image matrix = 48×48, slice thickness = 4 mm). Briefly, iopamidol (Isovue200, 1.5 mg I/g b.w.) was infused at a typical clinical dose via the tail vein using a syringe pump, with bolus injection of half of the dose at a rate of 18 ml/hr and continuous infusion of the rest of the contrast agent at a rate of 2 ml/hr during the CEST image acquisition to reduce the washin/washout effect for pH measurement (21). Respiratory gating was added before RF saturation and data acquisition to synchronize CEST preparation and single-shot SE EPI readout for acquisition of Z-spectra. WASSR map (frequency offsets between ±0.5 ppm with intervals of 0.05 ppm, B1=0.3 μT) and two Z-spectra (frequency offsets between ±7 ppm with intervals of 0.125 ppm, TR/TS/TE = 6,000/3,000/18 ms, averages=2) with B1 levels of 1.0 and 2.0 μT were collected (15). The total scan time for two Z-spectra was approximately 45 min.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed in MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA). Z-spectra (MZ) were centered using the WASSR map and normalized by the signal without RF irradiation (M0) (23, 24). The Z-spectra were inverted as (1–Mz/M0) and resolved using a multi-pool Lorentzian model,

| Eq. (1) |

where Li is the Lorentzian spectrum of the ith pool. Saturation transfer effects, including nuclear overhauser effect (NOE), magnetization transfer (MT), direct water saturation, iopamidol CEST effects of two hydroxyl groups (-OH) and two amide groups were solved using multi-pool Lorentzian model, with their chemical shifts at −3.2, −1.5, 0, 0.8, 1.8, 4.3 and 5.5 ppm, respectively (25–27),

| Eq. (2) |

where w is the frequency offset, A, w0and lw are the amplitude, center frequency and linewidth of the ith saturation transfer effects, respectively. Note that although the hydroxyl group at 0.8 ppm is close to the bulk water resonance and its CEST peak may appear indistinct to direct saturation, we assigned a Lorentzian function for every pool of exchangeable protons.

To minimize the bias of initial guesses, a recently developed Image Downsampling Expedited Adaptive Least-squares (IDEAL) fitting method was used (28). Briefly, CEST images were down-sampled to a single pixel to achieve a high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) for the initial fitting. Relaxed constraints were chosen, with peak and linewidth bounds between 1% and 100 times of the initial guesses, and the peak frequency shift within ±0.2 ppm of each chemical shift. CEST images were then resampled to 2×2, 4×4, 8×8, 12×12, 24×24 till the original resolution of 48×48, with the initial guesses of each voxel determined from the fitting results of the nearest voxel from the last down-sampled images. The constraints were reduced to between 10% and 10 times of the iterative initial values. Nonlinear constrained fitting algorithm was used with two-fold overweighting applied for Z-spectra between 4.0 and 5.8 ppm to increase the fitting accuracy of iopamidol CEST effects at 4.3 and 5.5 ppm. Goodness of fitting (R2) was calculated for each pixel. For the proposed resolved method, the ST effects were measured as the numerically determined amplitudes of the exchangeable chemical pools. Ratiometric measurement was obtained by ratioing multi-Lorentzian model resolved ST effects at 5.5 ppm obtained under B1 of 2.0 μT to that at 4.3 ppm obtained under B1 of 1.0 μT,

| Eq. (3) |

For the standard ratiometric methods, the ST effects at chemical shifts of 4.3 and 5.5 ppm were measured with asymmetric analysis of , where ω is the chemical shift of iopamidol amide proton with respective to the water resonance. In vitro pH calibration was obtained using a polynomial fitting of RST as a function of titrated pH (16), based on which absolute pH was calculated from ratiometric CEST effect per-pixel. The standard deviation of precision (SDP) was calculated (18). Renal pH from ratiometric analysis of the same RF power level (e.g. ST(5.5 ppm)/ST(4.3 ppm) under 1.0 and 2.0 μT) and mixed RF power levels (e.g. ST(5.5 ppm, 2.0 μT)/ST(4.3 ppm, 1.0 μT)) was investigated for both of the proposed resolved and standard ratiometric methods (Supplementary Information). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni correction was conducted and P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

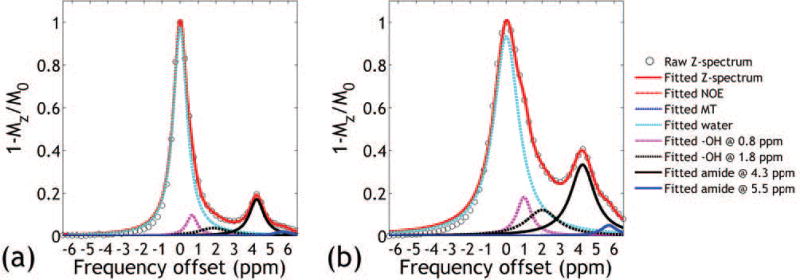

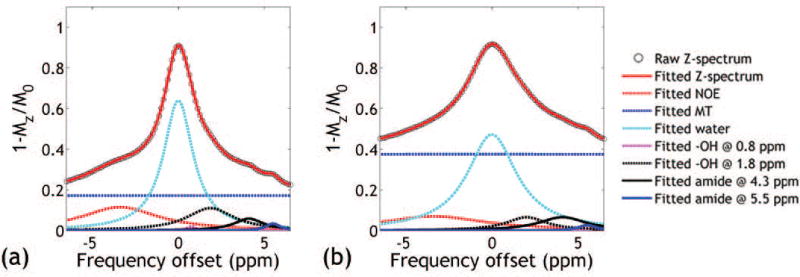

Figure 1 (pH = 7.0) and Supporting Figure S1 (pH = 6.0, 6.5 and 7.5) shows representative CEST Z-spectra from the iopamidol PBS phantoms obtained under B1 of 1.0 and 2.0 μT. There is substantial overlap between iopamidol CEST effects at 4.3 and 5.5 ppm especially at higher pH or under greater B1with 4.3 ppm signal much stronger than that of 5.5 ppm. Multi-pool Lorentzian line fitting (Eq. 1) resolves multiple overlapping CEST effects from the Z-spectrum, allowing improved calculation of the ratiometric analysis. Note that high R2s >0.99 were achieved for all vials and power levels, indicating good fitting performance.

Figure 1.

Multi-pool Lorentzian resolving of representative CEST Z-spectra obtained under B1 of (a) 1.0 μT and (b) 2.0 μT from the pH vial of 7.0.

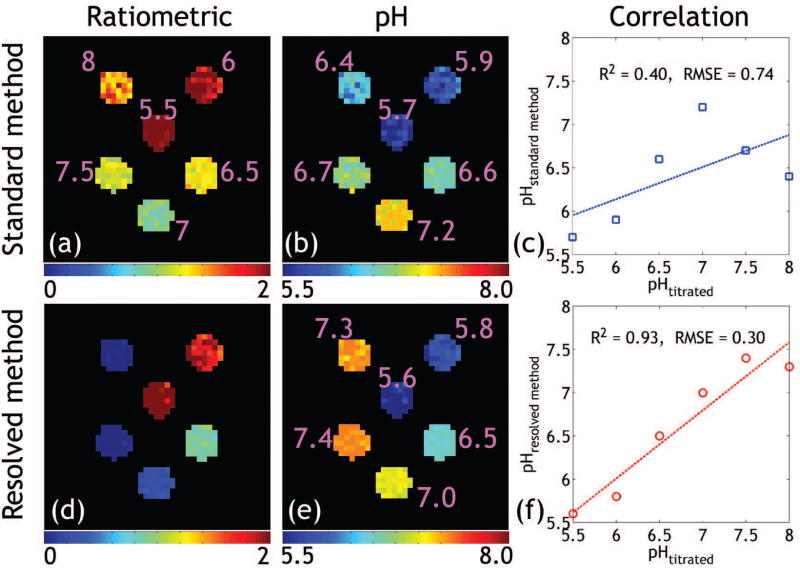

ST effects of iopamidol PBS phantom at 4.3 and 5.5 ppm under the saturation powers of 1.0 and 2.0 μT were measured with the standard and the proposed resolved methods, respectively (Supporting Figure S2). The standard ratiometric image (Fig. 2a) ratioing ST(5.5 ppm, 2.0 μT)/ST(4.3 ppm, 1.0 μT) can map pH up to 7.0 (Fig. 2b). Poor correlation was found between the titrated and measured pH using the standard method (Fig. 2c). In comparison, Figs. 2d shows the modified ratiometric image, which is sensitive to pH as high as 7.5 (Fig. 2e), extending from the relatively narrow pH range obtainable using the standard ratiometric analysis. Moreover, the proposed resolved method yielded much stronger correlation and smaller root-mean-square-error (RMSE) between the measured and titrated pH values (Fig. 2f) compared to that determined using the standard method.

Figure 2.

(a) Standard ratiometric images show good pH sensitivity until pH of 7.0 (b). The measured pH was poorly correlated with the titrated values (c). In comparison, the modified ratiometric image (d) obtained from the line-resolving can capture pH as high as 7.5 (e). (f) Strong correlation was found between the measured and the titrated pH values.

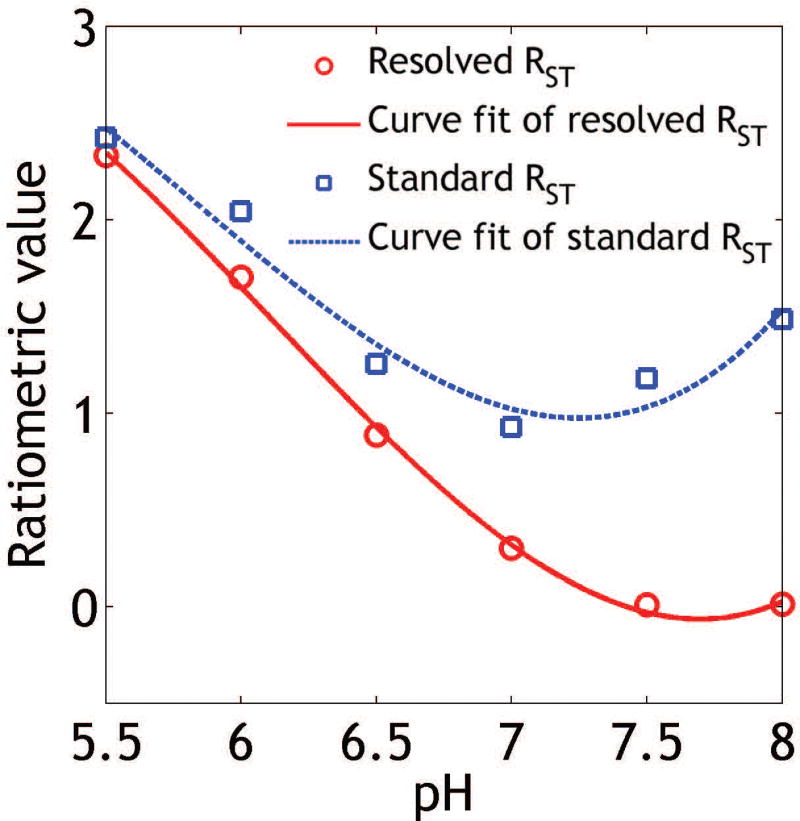

Figure 3 shows that the ratiometric analysis of resolved CEST effects extended the range of pH detection from that using the standard ratiometric analysis. Specifically, the routine ratiometric analysis (blue squares) has a narrow pH range of 5.5–7.0. This is because for pH above 7.0, the chemical exchange rate at 5.5 ppm becomes relatively fast with respect to that of 4.3 ppm, making it inefficient to detect using moderate RF saturation power levels. Note that the pH detection range established in vitro will likely be reduced in vivo due to more pronounced concomitant magnetization transfer and direct saturation effects in tissue. Fortunately, the modified ratiometric analysis of resolved CEST effects extended the pH detection range to 5.5–7.5 (SDP = 0.12 pH unit), aiding in vivo renal pH imaging.

Figure 3.

Extension of pH detection range using the modified ratiometric analysis (red circles) vs. that using the standard ratiometric approach (blue squares).

Figure 4 (cortex) and Supporting Figure S3 (calyx and medulla) show inverted Z-spectra (i.e., 1-Mz/M0) of a representative rat kidney following iopamidol injection, obtained under B1 of 1.0 μT and 2.0 μT, fitted with a multi-pool Lorentzian model. The amplitude of CEST effect at 5.5 ppm decreases from calyx to cortex under B1 of 2.0 μT, whereas the ST effect at 4.3 ppm shows relatively small change under B1 of 1.0 μT, suggesting consecutive renal pH decrease from the outermost to the innermost layers. Good fitting was observed for all layers with R2>0.99. We further confirmed that the modified ratiometric pH imaging provides improved renal pH mapping in vivo.

Figure 4.

Inverted Z-spectra measured at cortex from B1 of 1.0 μT (a) and 2.0 μT (b) were fitted using a multi-pool Lorentzian model.

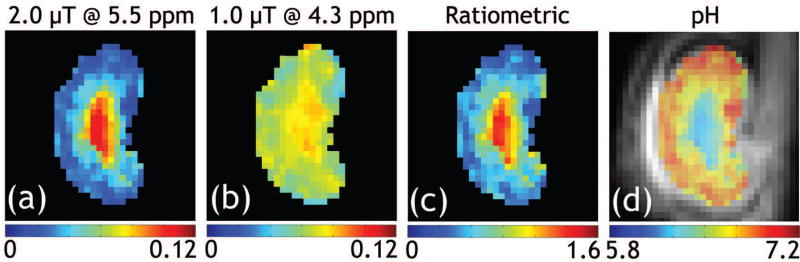

ST effects of a representative kidney at 4.3 and 5.5 ppm under the saturation powers of 1.0 and 2.0 μT were measured with the standard and the proposed resolved methods, respectively (Supporting Figure S4). Figures 5 a–c show resolved CEST effects at 5.5 ppm (2.0 μT), 4.3 ppm (1.0 μT) and the generalized ratiometric images, respectively. Good fitting was observed for the majority of voxels with R2>0.99 (not shown). Figure 5d shows renal pH map overlaid on a T2-weighted image. pH was found to be 7.0 ± 0.1, 6.8 ± 0.1 and 6.5 ± 0.2 for cortex, medulla and calyx, respectively, significantly different from each other (P<0.05). To demonstrate the advantage of the proposed resolved pH mapping, we investigated renal pH from ratiometric analysis of the same RF power level at 4.7 T (e.g. ST(5.5 ppm)/ST(4.3 ppm) under 1.0 μT (Supporting Figure S5) and 2.0 μT (Supporting Figure S6)) and ST(5.5 ppm, 2.0 μT)/ST(4.3 ppm, 1.0 μT) (Supporting Figure S7), all showing unsatisfactory results (Supporting Table S1) compared to previous findings (1, 16). For example, ratiometric analysis of ST(5.5 ppm)/ST(4.3 ppm) under 1.0 μT yielded underestimated renal pH of 6.4±0.2, 6.2±0.3 and 5.8±0.3 for cortex, medulla and calyx, respectively. This suggests that the presence of pronounced concomitant MT and direct saturation effects substantially confound in vivo pH determination using standard ratiometric analysis at sub-high/low field.

Figure 5.

Demonstration of renal pH map from a representative rat. The resolved maps of ST effects at (a) 5.5 and (b) 4.3 ppm were obtained with the proposed method, from which (c) the modified ratiometric map was obtained. (d) pH map overlaid on corresponding T2-weighted image shows renal pH gradually decreases from the cortex, medulla to calyx.

DISCUSSION

Our study generalized the routine ratiometric CEST analysis by mixing both RF power level and chemical shift for the ratiometric analysis, further applied multi-pool Lorentzian model to resolve overlapped CEST effects, and extended the range of pH detection at sub-high magnetic field. The approach was applied to measure renal pH in vivo, providing pH quantification in good agreement with prior findings at high field (2, 19).

It has been shown that chemical exchange rate of iopamidol amide groups at 4.3 and 5.5 ppm are both dominantly base-catalyzed, and the exchange rate at 5.5 ppm increases much more rapidly with pH than that at 4.3 ppm (26). In addition, it has been well recognized that it takes higher RF irradiation level to effectively saturate exchangeable groups undergoing faster chemical exchange. Therefore, we extended the ratiometric pH imaging by ratioing CEST effects at mixed RF power levels and offsets so that CEST effect at 5.5 ppm obtained under a higher RF power was normalized by CEST effect at 4.3 ppm using a slightly lower RF power level. This is in contrast to prior ratiometric analysis that ratios CEST effects at different chemical shifts obtained under the same saturation power or compares CEST effects at the same chemical shift obtained under different saturation levels. The proposed approach resolved confounding concomitant saturation effects, therefore, provides robust pH mapping. It helps to briefly discuss the selection of RF power levels for the modified ratiometric analysis. Previous study shows that the contrast-to–noise ratio of in vitro iopamidol pH imaging using the standard ratiometric pH analysis peaks for B1 of 2.5 μT at 4.7 T (26). To account for more pronounced concomitant MT and spillover effects in vivo, we reduced the B1 level to 2.0 μT. A second RF power level is needed for the generalized ratiometric pH analysis. We chose an intermediate RF power level of 1 μT to balance between sufficient CEST effects without excessive broadening.

To our knowledge, our study provides an initial attempt of imaging renal pH using iopamidol at 4.7 T that provided comparable pH measurements to those obtained at high field or using Gd-based contrast agents. Although we did not obtain independent measurements to directly calibrate the in vivo kidney pH measurements in this work, our results were similar to published and literature values. Briefly, we found that renal pH gradually decreases from cortex, medulla to calyx, similar to those obtained using Iopamidol pH MRI in a normal mouse model at 7 T (7.0 ± 0.11, 6.85 ± 0.15 and 6.6 ± 0.20 for cortex, medulla and calyx, respectively) (16) and pH-sensitive Gd-based contrast agent (7.3 ± 0.1, 7.0 ± 0.3 and 6.3 ± 0.5 for cortex, medulla and calyx, respectively) (1). The mean pH for the entire kidney was 6.9±0.1, also in good agreement with that reported previously (2, 19, 29). By referencing the corresponding pH and resolved saturation transfer effects at 4.3 and 5.5 ppm from the phantom, averaged iopamidol concentration estimated from the two saturation effects was 14.1±5.0, 16.9±3.5, and 20.9±7.1 mM in cortex, medulla and calyx, respectively. The normalized iopamidol concentration in cortex and medulla with respect to that in the calyx was 67±7% and 84±10%, respectively. The trend of normalized iopamidol concentration significantly increased from cortex, medulla to calyx, consistent with the known renal physiology. Note that the minimal iopamidol concentration was 8.8 mM in cortex from our study, suggesting the sensitivity to be at least 8.8 mM at 4.7 T. The minimum detectable concentration can be further improved with highly sensitive detection approach and/or application at higher field strength.

As the overlapping of CEST effects at 4.3 and 5.5 ppm is relatively small at high fields (e.g., 7 and 9.4 T), pH can be derived with the standard method as reported previously (2, 16, 19, 20, 29). Our study represents an initial effort toward clinical translation of iodinated-agents based pH MRI, and the methodology is promising to be translated to applications at common clinical field strength. In addition, our study acquired the complete Z-spectra from −7 to 7 ppm under the condition of constant infusion. With the development of more efficient field inhomogeneity correction techniques and post-processing algorithms, segments of Z-spectra could be used instead of the complete Z-spectra so that the total scan time may be substantially reduced.

It has been recognized that proper selection of initial guesses is critical for quantitative CEST fitting, particularly for cases with suboptimal SNR, relatively large range of pH, and heterogeneous contrast agent distribution. Our study here first increased SNR by down-sampling CEST-weighted images, and the enhanced SNR and relaxed constraints warrant good estimation of fitting coefficients. The fitting results determined under good SNR were used as initial guesses for the quantitative CEST analysis, enabling semiautomatic and adaptive fitting per pixel. Notably, this approach allows using a single set of initial guesses for the multi-pool Lorentzian model and fits all pixels in the kidney. Indeed, good fitting performance was achieved for both phantom and in vivo kidney studies.

CONCLUSION

Our study generalized the standard ratiometric CEST analysis, extended the iopamidol pH MRI detection range, and further demonstrated renal pH in vivo at sub-high magnetic field.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Figure S1. Multi-pool Lorentzian resolving of representative CEST Z-spectra obtained under B1 of (a–c) 1.0 μT and (d–f) 2.0 μT from pH vials of (a, d) 6.0, (b, e) 6.5, (c, f) 7.5.

Supporting Figure S2. ST effects of iopamidol PBS phantom at 4.3 and 5.5 ppm under the saturation powers of 1.0 and 2.0 μT were measured with the standard and the proposed resolved methods, respectively.

Supporting Figure S3. Inverted Z-spectra measured at calyx (a, b) and medulla (c, d) from B1 of 1.0 μT (left column) and 2.0 μT (right column) were fitted using a multi-pool Lorentzian model.

Supporting Figure S4. ST effects of a representative kidney at 4.3 and 5.5 ppm under the saturation powers of 1.0 and 2.0 μT were measured with the standard and the proposed resolved methods, respectively.

Supporting Figure S5. ST effects at (a) 5.5 ppm and (b) 4.3 ppm under the same saturation power of 1.0 μT were measured with the standard method, from which (c) the ratiometric map was obtained. (d) pH map overlaid on a T2-weighted image shows that pH values of most of the voxels in inner layers were less than 5.8, deviating from reported values.

Supporting Figure S6. ST effects at (a) 5.5 ppm and (b) 4.3 ppm under the same saturation power of 2.0 μT were measured with the standard method, from which (c) the ratiometric map was obtained. (d) pH map overlaid on a T2-weighted image shows that the renal pH values are apparently underestimated compared to reported values.

Supporting Figure S7. ST effects at (a) 5.5 ppm (B1=2.0 μT) and (b) 4.3 ppm (B1=1.0 μT) were measured with the standard method, from which (c) the ratiometric map was obtained. (d) pH map overlaid on a T2-weighted image shows that renal pH values at middle layers (<5.8) are smaller than those at calyx, inconsistent with reported values and renal pH pattern.

Supporting Table S1. Renal pH values measured by ratioing CEST effects at different chemical shifts of 5.5 and 4.3 ppm obtained under saturation powers of 1.0 and 2.0 μT with the standard and the proposed resolved methods. Mean ± standard deviation are presented.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81571668), National Basic Research Program of China (2015CB755500), Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (GJHZ20160229200622417) and National Institute of Health (R01NS083654).

References

- 1.Raghunand N, Howison C, Sherry AD, Zhang S, Gillies RJ. Renal and systemic pH imaging by contrast-enhanced MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49(2):249–257. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Longo DL, Busato A, Lanzardo S, Antico F, Aime S. Imaging the pH evolution of an acute kidney injury model by means of iopamidol, a MRI-CEST pH-responsive contrast agent. Magn Reson Med. 2013;70(3):859–864. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang F, Kopylov D, Zu Z, Takahashi K, Wang S, Quarles CC, Gore JC, Harris RC, Takahashi T. Mapping murine diabetic kidney disease using chemical exchange saturation transfer MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2016;76(5):1531–1541. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stubbs M, Bhujwalla ZM, Tozer GM, Rodrigues LM, Maxwell RJ, Morgan R, Howe FA, Griffiths JR. An assessment of 31P MRS as a method of measuring pH in rat tumours. NMR Biomed. 1992;5(6):351–359. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1940050606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Sluis R, Bhujwalla ZM, Raghunand N, Ballesteros P, Alvarez J, Cerdan S, Galons JP, Gillies RJ. In vivo imaging of extracellular pH using 1H MRSI. Magn Reson Med. 1999;41(4):743–750. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199904)41:4<743::aid-mrm13>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garcia-Martin ML, Herigault G, Remy C, Farion R, Ballesteros P, Coles JA, Cerdan S, Ziegler A. Mapping extracellular pH in rat brain gliomas in vivo by 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging: comparison with maps of metabolites. Cancer Res. 2001;61(17):6524–6531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gallagher FA, Kettunen MI, Day SE, Hu DE, Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH, Zandt R, Jensen PR, Karlsson M, Golman K, Lerche MH, Brindle KM. Magnetic resonance imaging of pH in vivo using hyperpolarized 13C-labelled bicarbonate. Nature. 2008;453(7197):940–943. doi: 10.1038/nature07017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alvarez-Perez J, Ballesteros P, Cerdan S. Microscopic images of intraspheroidal pH by 1H magnetic resonance chemical shift imaging of pH sensitive indicators. MAGMA. 2005;18(6):293–301. doi: 10.1007/s10334-005-0013-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang S, Wu K, Sherry AD. A Novel pH-Sensitive MRI Contrast Agent. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1999;38(21):3192–3194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garcia-Martin ML, Martinez GV, Raghunand N, Sherry AD, Zhang S, Gillies RJ. High resolution pH(e) imaging of rat glioma using pH-dependent relaxivity. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55(2):309–315. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beauregard DA, Parker D, Brindle KM. Proceedings of the 6th Annual Meeting of ISMRM. Sydney, Australia: 1998. Relaxation-based mapping of tumor pH; p. 53. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frullano L, Catana C, Benner T, Sherry AD, Caravan P. Bimodal MR-PET agent for quantitative pH imaging. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2010;49(13):2382–2384. doi: 10.1002/anie.201000075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aime S, Calabi L, Biondi L, De Miranda M, Ghelli S, Paleari L, Rebaudengo C, Terreno E. Iopamidol: Exploring the potential use of a well-established x-ray contrast agent for MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2005;53(4):830–834. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ward KM, Balaban RS. Determination of pH using water protons and chemical exchange dependent saturation transfer (CEST) Magn Reson Med. 2000;44(5):799–802. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200011)44:5<799::aid-mrm18>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu R, Longo DL, Aime S, Sun PZ. Quantitative description of radiofrequency (RF) power-based ratiometric chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) pH imaging. NMR Biomed. 2015;28(5):555–565. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Longo DL, Dastru W, Digilio G, Keupp J, Langereis S, Lanzardo S, Prestigio S, Steinbach O, Terreno E, Uggeri F, Aime S. Iopamidol as a responsive MRI-chemical exchange saturation transfer contrast agent for pH mapping of kidneys: In vivo studies in mice at 7 T. Magn Reson Med. 2011;65(1):202–211. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheth VR, Liu G, Li Y, Pagel MD. Improved pH measurements with a single PARACEST MRI contrast agent. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2012;7(1):26–34. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moon BF, Jones KM, Chen LQ, Liu P, Randtke EA, Howison CM, Pagel MD. A comparison of iopromide and iopamidol, two acidoCEST MRI contrast media that measure tumor extracellular pH. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2015;10(6):446–455. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang X, Song X, Ray Banerjee S, Li Y, Byun Y, Liu G, Bhujwalla ZM, Pomper MG, McMahon MT. Developing imidazoles as CEST MRI pH sensors. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2016;11(4):304–312. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu Y, Zhang S, Soesbe TC, Yu J, Vinogradov E, Lenkinski RE, Sherry AD. pH imaging of mouse kidneys in vivo using a frequency-dependent paraCEST agent. Magn Reson Med. 2016;75(6):2432–2441. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Longo DL, Sun PZ, Consolino L, Michelotti FC, Uggeri F, Aime S. A general MRI-CEST ratiometric approach for pH imaging: demonstration of in vivo pH mapping with iobitridol. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136(41):14333–14336. doi: 10.1021/ja5059313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muller-Lutz A, Khalil N, Schmitt B, Jellus V, Pentang G, Oeltzschner G, Antoch G, Lanzman RS, Wittsack HJ. Pilot study of Iopamidol-based quantitative pH imaging on a clinical 3T MR scanner. MAGMA. 2014;27(6):477–485. doi: 10.1007/s10334-014-0433-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stancanello J, Terreno E, Castelli DD, Cabella C, Uggeri F, Aime S. Development and validation of a smoothing-splines-based correction method for improving the analysis of CEST-MR images. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2008;3(4):136–149. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim M, Gillen J, Landman BA, Zhou J, van Zijl PC. Water saturation shift referencing (WASSR) for chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) experiments. Magn Reson Med. 2009;61(6):1441–1450. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cai K, Singh A, Poptani H, Li W, Yang S, Lu Y, Hariharan H, Zhou XJ, Reddy R. CEST signal at 2ppm (CEST@2ppm) from Z-spectral fitting correlates with creatine distribution in brain tumor. NMR Biomed. 2015;28(1):1–8. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun PZ, Longo DL, Hu W, Xiao G, Wu R. Quantification of iopamidol multi-site chemical exchange properties for ratiometric chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) imaging of pH. Phys Med Biol. 2014;59(16):4493–4504. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/59/16/4493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zaiss M, Schmitt B, Bachert P. Quantitative separation of CEST effect from magnetization transfer and spillover effects by Lorentzian-line-fit analysis of z-spectra. J Magn Reson. 2011;211(2):149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou IY, Wang E, Cheung JS, Zhang X, Fulci G, Sun PZ. Quantitative chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) MRI of glioma using Image Downsampling Expedited Adaptive Least-squares (IDEAL) fitting. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):84. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00167-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Longo DL, Cutrin JC, Michelotti F, Irrera P, Aime S. Noninvasive evaluation of renal pH homeostasis after ischemia reperfusion injury by CEST-MRI. NMR Biomed. 2017 doi: 10.1002/nbm.3720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Figure S1. Multi-pool Lorentzian resolving of representative CEST Z-spectra obtained under B1 of (a–c) 1.0 μT and (d–f) 2.0 μT from pH vials of (a, d) 6.0, (b, e) 6.5, (c, f) 7.5.

Supporting Figure S2. ST effects of iopamidol PBS phantom at 4.3 and 5.5 ppm under the saturation powers of 1.0 and 2.0 μT were measured with the standard and the proposed resolved methods, respectively.

Supporting Figure S3. Inverted Z-spectra measured at calyx (a, b) and medulla (c, d) from B1 of 1.0 μT (left column) and 2.0 μT (right column) were fitted using a multi-pool Lorentzian model.

Supporting Figure S4. ST effects of a representative kidney at 4.3 and 5.5 ppm under the saturation powers of 1.0 and 2.0 μT were measured with the standard and the proposed resolved methods, respectively.

Supporting Figure S5. ST effects at (a) 5.5 ppm and (b) 4.3 ppm under the same saturation power of 1.0 μT were measured with the standard method, from which (c) the ratiometric map was obtained. (d) pH map overlaid on a T2-weighted image shows that pH values of most of the voxels in inner layers were less than 5.8, deviating from reported values.

Supporting Figure S6. ST effects at (a) 5.5 ppm and (b) 4.3 ppm under the same saturation power of 2.0 μT were measured with the standard method, from which (c) the ratiometric map was obtained. (d) pH map overlaid on a T2-weighted image shows that the renal pH values are apparently underestimated compared to reported values.

Supporting Figure S7. ST effects at (a) 5.5 ppm (B1=2.0 μT) and (b) 4.3 ppm (B1=1.0 μT) were measured with the standard method, from which (c) the ratiometric map was obtained. (d) pH map overlaid on a T2-weighted image shows that renal pH values at middle layers (<5.8) are smaller than those at calyx, inconsistent with reported values and renal pH pattern.

Supporting Table S1. Renal pH values measured by ratioing CEST effects at different chemical shifts of 5.5 and 4.3 ppm obtained under saturation powers of 1.0 and 2.0 μT with the standard and the proposed resolved methods. Mean ± standard deviation are presented.