Abstract

AIM

To examine temporal changes in the indications for liver transplantation (LT) and characteristics of patients transplanted for alcoholic liver disease (ALD).

METHODS

We performed a retrospective cohort analysis of trends in the indication for LT using the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) database between 2002 and 2015. Patients were grouped by etiology of the liver disease and characteristics were compared using χ2 and t-tests. Time series analysis was used identifying any year with a significant change in the number of transplants per year for ALD, and before and after eras were modeled using a general linear model. Subgroup analysis of recipients with ALD was performed by age group, gender, UNOS region and etiology (alcoholic cirrhosis, alcoholic hepatitis and hepatitis C - alcoholic cirrhosis dual listing).

RESULTS

Of 74216 liver transplant recipients, ALD (n = 9400, 12.7%) was the third leading indication for transplant after hepatitis C and hepatocellular carcinoma. Transplants for ALD, increased from 12.8% (553) in 2002 to 16.5% (1020) in 2015. Time series analysis indicated a significant increase in the number of transplants per year for ALD in 2013 (P = 0.03). There were a stable number of transplants per year between 2002 and 2012 (linear coefficient 3, 95%CI: -4.6, 11.2) an increase of 177 per year between 2013 and 2015 (95%CI: 119, 234). This increase was significant for all age groups except those 71-83 years old, was observed for both genders, and was incompletely explained by a decrease in transplants for hepatitis C and ALD dual listing. All UNOS regions except region 9 saw an increase in the mean number of transplants per year when comparing eras, and this increase was significant in regions 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10 and 11.

CONCLUSION

There has been a dramatic increase in the number of transplants for ALD starting in 2013.

Keywords: Alcoholic liver disease, Liver transplantation, Cirrhosis, Epidemiology, Hepatitis C

Core tip: Although the number of liver transplants done for alcoholic liver disease (ALD) has been stable been 2002 and 2012, since 2013 there has been a significant increase. This increase is seen across all age groups, although the proportional increases are higher for younger patients than older ones. The increase corresponds, but is incompletely explained, by a decrease in transplants for hepatitis C - ALD dual listing. The increase was also seen in most, but not all UNOS regions.

INTRODUCTION

Liver transplantation (LT) has become a life-saving procedure for patients with irreversible liver diseases. A total of 7841 liver transplants were performed in 2016 in the United States with 14389 potential recipients on the waiting list[1]. One of the common causes of chronic liver disease for which LT is potentially life saving is alcoholic liver disease (ALD). Progression of ALD is dependent on patient characteristics (sex, race, ethnicity, malnutrition), genetic factors, coexisting liver pathology [e.g., hepatitis C virus (HCV) or non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)] as well as drinking patterns (volume consumed, drinking outside meal times, binge drinking, and duration of consumption). The risk of developing cirrhosis is increased with consumption of > 60-80 g/d of alcohol for ≥ 10 years for men and > 20-40 g/d in women[2,3]. However, despite drinking at these levels, only 6%-41% of people develop cirrhosis[2,4].

Population-based studies have shown that although the proportion of the population who drink any alcohol is not increasing, there has been an increase in the prevalence of both heavy drinking (defined as more than 1 drink per day for women or 2 drinks per day for men, on average) and binge drinking (defined as at least 4 drinks for women or 5 for men in the last thirty days)[5]. Heavy drinking has been shown to increase the risk of ALD and all-cause mortality[6]. Because we have noticed a recent increase in the number of referrals to our transplant center for ALD, we decided to critically review the temporal and geographic trends in the LT for ALD and examine characteristics of patients transplanted for ALD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data source

We conducted a retrospective cohort analysis of transplant recipients in the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) Standard Transplant Analysis and Research file. United States donor data for this analysis is Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network data released 2016-06-17 based on data collected through 2016-03-31. UNOS as the contractor for the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network supplied this data. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as an official policy of or interpretation by the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network or the United States Government. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Dr. James Perkins from the University of Washington. This study met expedited review criteria as approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board.

Study population and temporal trends

We identified all liver transplant recipients in the UNOS database from 2002 to 2015 and characterized them according to the etiology of their liver disease. The category ALD was defined as recipients with a diagnosis of alcoholic cirrhosis or acute alcoholic hepatitis. However, in order to minimize the effect of concomitant liver disease, we categorized those with a listing diagnosis of both HCV and alcoholic cirrhosis (HCV/ALD) as HCV.

Recipient characteristics were compared among the leading four etiologies of cirrhosis using χ2 test for categorical values and student’s t-test used for continuous variables. The number of transplants per year by liver disease was graphed to illustrate changes over time.

ALD subgroup analysis

We performed a subgroup analysis of recipients transplanted for ALD. Temporal trends in recipient characteristics were studied and compared using χ2 test for categorical values and student’s t-test used for continuous variables. We then used time series analysis to identify any year with a significant change in the number of transplants per year, and then compared transplant rates in the “before” and “after” eras. To model transplant growth in each era, we used a spline linear regression model with the cut point at the year predicted by the time series analysis.

To determine if age or gender had any affect on change in transplant rates, we also compared mean transplants per year in the before and after eras for categorical age groups (18-30, 31-40, 41-50, 51-60, 61-70 and 71-83 years old) and gender using student’s t-test. We also used this method to evaluate the contribution of transplants for acute alcoholic hepatitis, separating the ALD population into acute alcoholic hepatitis from alcoholic cirrhosis subgroups. We hypothesized that the increasing use of curative treatment for HCV cirrhosis could lead to a change in the classification of cirrhosis etiology, such that patients previously listed as HCV/ALD were subsequently listed as alcoholic cirrhosis alone. Hence, we analyzed the change in time for the HCV/ALD population using the same approach as above.

Analysis of transplant changes by region

UNOS is an organization involved in many aspects of the organ transplant and donation process and operates by grouping states into several different regions throughout the country. To facilitate transplantation, the US is divided into 11 geographic regions. Liver transplant recipients were grouped by UNOS region and the mean number of transplants per region per year for the before and after eras was calculated.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were conducted using JMP Pro 13.0.0 (SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC) statistical software, graphics were made in Stata 12.1 (College Station, TX, United States).

RESULTS

Study population

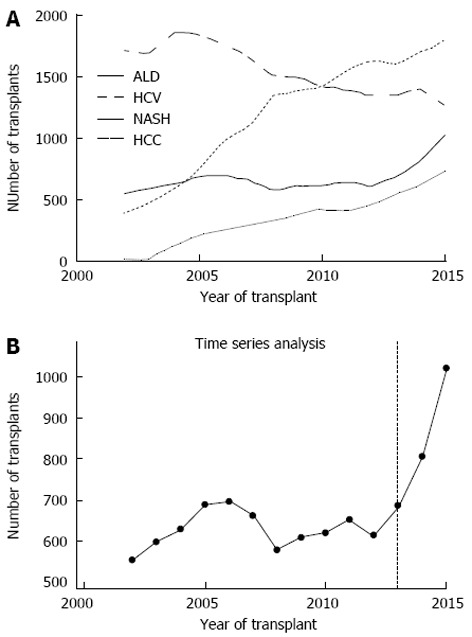

Of 74216 liver transplant recipients, ALD (n = 9400, 12.7%) was the third leading indication for transplant after HCV (n = 21707, 29.2%) and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (n = 16627, 22.4%) (Figure 1A). Recipients with ALD were younger, more likely to be non-black and have a higher model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) at transplant than recipients with HCV, HCC or NASH cirrhosis (Table 1). Time series analysis demonstrated a significant increase in the number of transplants for ALD starting in 2013 (P = 0.03) (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Time series analysis demonstrated a significant increase in the number of transplants for alcoholic liver disease starting in 2013. A: Number of transplants per year by etiology of liver disease; B: Time series analysis of alcoholic liver disease liver transplant recipients demonstrating a significant change in the number of transplants starting in 2013 (P = 0.03). ALD: Alcoholic liver disease; HCV: Hepatitis C virus; NASH: Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma.

Table 1.

Recipient characteristics by etiology of liver disease

| HCV 21707 (29.2%) | HCC 16627 (22.4%) | ALD 9400 (12.7%) | NASH 4745 (6.4%) | P value | |

| Age | 54.1 ± 7.19 | 57.9 ± 7.8 | 53.5 ± 9.02 | 56.7 ± 10.2 | < 0.001 |

| Female | 5799 (26.7%) | 3928 (23.6%) | 2210 (23.5%) | 2237 (47.1%) | < 0.001 |

| Race | < 0.001 | ||||

| White | 15408 (71.0%) | 11133 (67.0%) | 7533 (80.1%) | 4006 (84.4%) | |

| Hispanic | 3071 (14.2%) | 2496 (15.0%) | 1285 (13.7%) | 524 (11%) | |

| Black | 2504 (11.5%) | 1542 (9.3%) | 371 (4.0%) | 95 (2%) | |

| Other | 724 (3.3%) | 1456 (8.8%) | 211 (2.2%) | 120 (2.5%) | |

| BMI | 28.4 ± 5.3 | 28.3 ± 5.3 | 27.9 ± 5.41 | 32 ± 6.1 | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes | < 0.001 | ||||

| None | 16912 (77.9%) | 11741 (70.6%) | 7440 (79.2%) | 2139 (45.1%) | |

| Any | 4430 (20.4%) | 4733 (28.5%) | 1828 (19.5%) | 2545 (53.6%) | |

| Unknown | 365 (1.7%) | 153 (0.9%) | 132 (1.4%) | 61 (1.3%) | |

| MELD at transplant | 22 ± 10 | 15 ± 8.3 | 25.1 ± 9.6 | 23.8 ± 9.2 | < 0.001 |

| HCC in explant | 3919 (18.1%) | 11034 (66.4%) | 482 (5.1%) | 260 (5.5%) | < 0.001 |

HCV: Hepatitis C virus; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; ALD: Alcoholic liver disease; NASH: Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; BMI: Body mass index.

ALD subgroup analysis

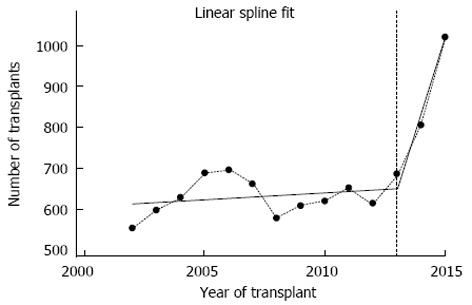

The total number of transplants performed for ALD increased from 553 (12.8% of the annual total) in 2002 to 1020 (16.5%) in 2015 (Table 2). Age and BMI remained unchanged over the study period, but there was a significant increase in the proportion of female recipients (from 22.4% in 2002 to 27.5% in 2015, P = 0.001) and an increase in MELD (20.6 ± 8.4 in 2002 to 28.9 ± 10.4 in 2015, P < 0.001). In the before era, the number of transplants per year was stable as predicted by the linear spline model (coefficient 3.3, 95%CI: -4.6, 11.2). In the after era, there were approximately 177 more transplants per year for ALD (coefficient 176.7, 95%CI: 119.4, 234.0) (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Temporal trends in characteristics of alcoholic liver disease liver transplant recipients

| 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | P value | |

| n (% annual) | 553 (12.8%) | 597 (12.8%) | 628 (12.4%) | 688 (13.0%) | 695 (12.7%) | 660 (12.3%) | 578 (11.1%) | 608 (11.6%) | 619 (11.7%) | 651 (12.1%) | 613 (11.4%) | 685 (12.4%) | 805 (13.9%) | 1020 (16.5%) | |

| Age | 53.0 ± 8.2 | 52.9 ± 8.5 | 54.0 ± 8.8 | 53.4 ± 8.6 | 53.7 ± 8.6 | 54.5 ± 8.7 | 53.6 ± 8.9 | 54.3 ± 8.5 | 54.1 ± 8.9 | 54.0 ± 8.9 | 53.6 ± 8.9 | 52.8 ± 9.4 | 53.7 ± 9.7 | 52.5 ± 10.2 | 0.1 |

| Female | 124 (22.4%) | 126 (21.1%) | 125 (19.9%) | 134 (19.5%) | 156 (22.4%) | 133 (20.2%) | 127 (22.0%) | 146 (24.0%) | 164 (26.5%) | 170 (26.1%) | 153 (25.0%) | 172 (25.1%) | 200 (24.8%) | 280 (27.5%) | 0.001 |

| Race | 0.03 | ||||||||||||||

| Black | 15 (2.7%) | 16 (2.7%) | 23 (3.7%) | 24 (3.5%) | 32 (4.6%) | 19 (2.9%) | 21 (3.6%) | 22 (3.6%) | 18 (2.9%) | 37 (5.7%) | 23 (3.8%) | 35 (5.1%) | 38 (4.7%) | 48 (4.7%) | |

| Hispanic | 71 (12.8%) | 76 (12.7%) | 76 (12.1%) | 77 (11.2%) | 98 (14.1%) | 98 (14.8%) | 95 (16.4%) | 79 (13.0%) | 85 (13.7%) | 88 (13.5%) | 93 (15.2%) | 96 (14.0%) | 103 (12.8%) | 150 (14.7%) | |

| Other | 6 (1.1%) | 12 (2.0%) | 13 (2.1%) | 12 (1.7%) | 9 (1.3%) | 12 (1.8%) | 16 (2.8%) | 9 (1.5%) | 20 (3.2%) | 16 (2.5%) | 13 (2.1%) | 18 (2.6%) | 17 (2.1%) | 38 (3.7%) | |

| White | 461 (83.4%) | 493 (82.6%) | 516 (82.2%) | 575 (83.6%) | 556 (80.0%) | 531 (80.5%) | 446 (77.2%) | 498 (81.9%) | 496 (80.1%) | 510 (78.3%) | 484 (79.0%) | 536 (78.2%) | 647 (80.4%) | 784 (76.9%) | |

| BMI | 27.7 ± 5.3 | 27.8 ± 5.2 | 27.7 ± 5.5 | 27.9 ± 5.4 | 27.7 ± 5.4 | 28.4 ± 5.5 | 27.9 ± 5.4 | 27.9 ± 5.4 | 28.0 ± 5.6 | 27.9 ± 5.5 | 28.1 ± 5.4 | 28.0 ± 5.3 | 27.8 ± 5.4 | 28.0 ± 5.5 | 0.3 |

| Diabetes | < 0.001 | ||||||||||||||

| None | 433 (78.3%) | 458 (76.7%) | 493 (78.5%) | 538 (78.2%) | 548 (78.8%) | 484 (73.3%) | 440 (76.1%) | 485 (79.8%) | 487 (78.7%) | 518 (79.6%) | 509 (83.0%) | 560 (81.8%) | 659 (81.9%) | 828 (81.2%) | |

| Any | 103 (18.6%) | 122 (20.4%) | 116 (18.5%) | 138 (20.1%) | 134 (19.3%) | 167 (25.3%) | 131 (22.7%) | 109 (17.9%) | 127 (20.5%) | 128 (19.7%) | 100 (16.3%) | 122 (17.8%) | 144 (17.9%) | 187 (18.3%) | |

| Unknown | 17 (3.1%) | 17 (2.8%) | 19 (3.0%) | 12 (1.7%) | 13 (1.9%) | 9 (1.4%) | 7 (1.2%) | 14 (2.3%) | 5 (0.8%) | 5 (0.8%) | 4 (0.7%) | 3 (0.4%) | 2 (0.2%) | 5 (0.5%) | |

| MELD | 20.6 ± 8.4 | 21.6 ± 9.2 | 22.6 ± 9.5 | 22.6 ± 8.7 | 22.8 ± 8.5 | 23.9 ± 8.9 | 24.8 ± 9.0 | 25.1 ± 8.7 | 25.8 ± 9.4 | 26.1 ± 9.5 | 27.0 ± 9.3 | 27.5 ± 9.7 | 28.1 ± 9.6 | 28.9 ± 10.4 | < 0.001 |

| HCC in explant | 58 (10.5%) | 41 (6.9%) | 51 (8.1%) | 37 (5.4%) | 44 (6.3%) | 39 (5.9%) | 30 (5.2%) | 23 (3.8%) | 18 (2.9%) | 27 (4.1%) | 24 (3.9%) | 28 (4.1%) | 23 (2.9%) | 39 (3.8%) | < 0.001 |

BMI: Body mass index; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma.

Figure 2.

Linear spline fit for number of transplants for year for alcoholic liver disease in the before and after eras.

All age groups except those 71-83 years old showed a significant increase in the mean number of transplants per year for ALD when comparing before and after eras, but the greatest proportional increase was seen in the youngest recipients (Table 3). The proportional increase in mean transplants per year was greater in females than males, and was significant for both genders (P = 0.001, 0.005, respectively). Although there was a 1.4 fold increase in transplants for alcoholic hepatitis, this was not statistically significant (P = 0.58), only represented an increase of approximately 3 transplants per year, and did not explain the overall increase in transplants for ALD. As expected, there was a decrease in transplants for HCV/ALD, however this decrease (90.7 transplants per year) was much less than the per year increase for ALD (210.3 transplants per year).

Table 3.

Changes in number of transplants per year for alcoholic liver disease by age group, gender and etiology

| Mean per year 2002-2012 | Mean per year 2013-2015 | Difference | Change | P value | |

| Total | 626.4 | 836.7 | 210.3 | 1.34 | 0.002 |

| Age group (yr) | |||||

| 18-30 | 4.3 | 14.3 | 10.1 | 3.35 | 0.003 |

| 31-40 | 40.7 | 84.0 | 43.3 | 2.06 | 0.001 |

| 41-50 | 170.5 | 219.7 | 49.1 | 1.29 | 0.005 |

| 51-60 | 264.5 | 314.3 | 49.8 | 1.19 | 0.040 |

| 61-70 | 138.4 | 195.0 | 56.6 | 1.41 | 0.010 |

| 71-83 | 7.9 | 9.3 | 1.4 | 1.18 | 0.500 |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 141.6 | 217.3 | 75.7 | 1.53 | 0.001 |

| Male | 484.7 | 619.3 | 134.6 | 1.28 | 0.005 |

| Etiology | |||||

| Alcoholic cirrhosis | 619.5 | 827.0 | 207.5 | 1.33 | 0.002 |

| Alcoholic hepatitis | 6.8 | 9.7 | 2.8 | 1.42 | 0.580 |

| HCV/ALD | 274.4 | 183.7 | -90.7 | 0.67 | 0.050 |

HCV: Hepatitis C virus; ALD: Alcoholic liver disease.

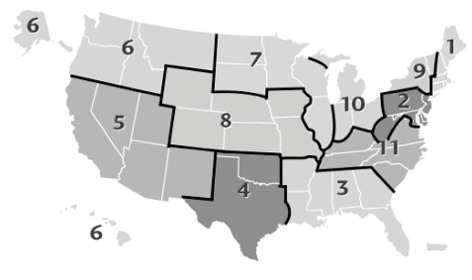

Analysis of transplant and alcohol use by region

All regions except region 9 saw an increase in the mean number of transplants per year when comparing eras, and this increase was significant in regions 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10 and 11 (Table 4, Figure 3).

Table 4.

Changes in number of transplants per year for alcoholic liver disease by UNOS region

| UNOS region | Mean per year 2002-2012 | Mean per year 2013-2015 | Difference | Change | P value |

| 1 | 28.5 | 37.3 | 8.8 | 1.31 | 0.09 |

| 2 | 86.0 | 120.3 | 34.3 | 1.40 | 0.01 |

| 3 | 103.4 | 142.7 | 39.3 | 1.38 | 0.02 |

| 4 | 54.1 | 75.7 | 21.6 | 1.40 | 0.05 |

| 5 | 75.5 | 117.3 | 41.8 | 1.55 | 0.003 |

| 6 | 13.0 | 24.7 | 11.7 | 1.90 | 0.001 |

| 7 | 83.1 | 89.0 | 5.9 | 1.07 | 0.32 |

| 8 | 33.6 | 52.3 | 18.7 | 1.56 | 0.002 |

| 9 | 43.4 | 28.3 | -15.0 | 0.65 | 0.23 |

| 10 | 52.3 | 71.0 | 18.7 | 1.36 | 0.03 |

| 11 | 53.5 | 78.0 | 24.5 | 1.46 | 0.005 |

Figure 3.

UNOS regions in the United States[29].

DISCUSSION

In a nationwide cohort of liver recipients, we found that the number of transplants for ALD was stable between 2002 and 2012, but rose by approximately 177 transplants per year between 2013 and 2015. This increase was observed more in young recipients and in females and was incompletely explained by a decrease in transplants for HCV/ALD. There was a significant increase in 8 out 11 UNOS regions, and a decrease only in region 9. This increase in transplants for ALD has not been previously described.

Prior epidemiologic studies on the indication for liver transplant have shown stable to decreasing rates of transplants for ALD, but these studies were based on data collected before 2013[7,8]. However, a more recent study noted an increase in transplants for ALD in recent years, which is more rapid than that for NASH[9]. Population-based studies have shown an increase in heavy alcohol use[5], binge drinking[5] and per capita alcohol use[10] since the early 2000s. During the same time period, there was an increase in hospitalization for alcohol-related diagnosis and an increase in age-adjusted death rates from ALD[11,12]. Furthermore, the proportion of cirrhosis-related deaths attributable to alcohol have increased in young patients (25-54 years old)[12]. However, other data suggest decreasing overall prevalence of ALD in the population[9].

The reason for this increase in transplants for ALD starting in 2013 is uncertain. Our data suggest that the surge is not due to an increasing BMI in this population or an increase in transplants for acute alcoholic hepatitis, and it is not solely due to reclassification of HCV/ALD transplants as ALD. There has been a steady increase in the number of new waitlistings for ALD, but the rate of rise of transplants since 2013 seems to exceed the rate of rise of listings[9]. Perhaps there has been a recent improvement in both the referral for transplant and wait-listing for patients with ALD, who have historically have lower rates of both referral[13,14] and waitlist[15]. The American Association for the Study of Liver disease revised the “Evaluation for Liver Transplantation in Adults Practice Guidelines” in 2005[16] and again 2013[17]. The 2005 Guidelines recommended “it is prudent to delay transplantation for a minimum of 3-6 mo of abstinence from alcohol.” However, in the 2013 guidelines it was acknowledged that 6 mo of sobriety before referral “may result in deterioration of the patient’s medical condition so that psychosocial or addiction requirements determined from the initial evaluation may not be achievable.” While there is not a temporal relationship between this publication (March 2014) and our observed increased in transplants for ALD (start of 2013), the 2013 Guidelines may reflect a developing leniency of the abstinence requirement amongst transplant programs.

ALD is historically the second most common etiology for LT in the European Liver Transplant Registry at 33.6%, trailing only virus related cirrhosis. However, in the setting of treatment for HCV, ALD has become the leading indication for LT[18]. There has been a sustained increase in the proportion of transplants performed for ALD since the late-1980s, including 2013-2015. In a Nordic paper, the proportion of transplants for ALD remained relatively constant between 1994 and 2013[19].

Early identification of problematic alcohol use and reduction in drinking has the potential to change the pattern we have described. Only 10% of patients with drinking problems are identified by primary care providers, and under-diagnosis is common in teenagers[20]. Brief interventions in the primary care setting can result in reduced consumption and may subsequently reduce alcohol-related harm and mortality[21,22]. After a single course of treatment by a qualified alcohol counselor, abstinent rates are 17 to 33% and an additional 7% to 12% reduce their intake[23].

There are several simple screening tools for alcohol use that are designed to be highly sensitive and easy to use in the primary care setting. The CAGE questionnaire is a 4-question test with binary answers; two “yes” responses are considered a positive test and should prompt additional testing[24,25]. Alternatively, the more extensive alcohol use disorders identification test was developed by the World Health Organization and consists of ten questions with five possible answers and a focus on identification of heavy drinkers[26,27]. Another option is a single screening question “How many times in the past year have you had 5 (males) or 4 (females) or more drinks in a day?” with a cutoff of 8 times, and can also be used to accurately identify patients with unhealthy alcohol use with good discrimination[28]. The widespread use of electronic medical records make systematic implementation of well validated tools inexpensive and quite practical. This would follow the approach for identification of smoking using the electronic medical record. The potential for this approach on the prognosis of patients with ALD could be profound.

There were several limitations to our study. We examined only patients transplanted for ALD, not those listed for transplantation, so we are unable to determine whether the increase observed is due to an increasing listing for ALD or an increase in the proportion of waitlisted patients with ALD undergoing transplant. However, Goldberg et al[29] recently showed a steeper rate of rise for LTs for ALD than absolute number of new waitlistings, although both are increasing. Additionally, we were unable to further explore why all but three UNOS regions demonstrated an increase in transplants for ALD.

In conclusion, in this study we demonstrate a nationwide increase in the number of transplants per year for ALD beginning in 2013, particularly in young and female patients. The reason for this increase is unknown, but comes in the setting of widespread and increasing alcohol use and hospital admissions for ALD. Consideration should be given to the use of screening tools aimed at detecting alcohol use in the primary care setting to identify patients with problematic alcohol use and promote reduction in consumption in order to avoid harm.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Liver transplantation (LT) has become a life-saving procedure for patients with irreversible liver diseases. One of the common causes of chronic liver disease for which LT is potentially life-saving is alcoholic liver disease (ALD).

Research motivation

Population-based studies have shown that there has been an increase in the prevalence of both heavy drinking and binge drinking.

Research methods

Authors conducted a retrospective cohort analysis of transplant recipients in the United Network for Organ Sharing Standard Transplant Analysis and Research file.

Research results

Between 2002 and 2015, ALD was the third leading indication for transplant after HCV and hepatocellular carcinoma. The total number of transplants performed for ALD increased from 553 (12.8% of the annual total) in 2002 to 1020 (16.5%) in 2015.

Research conclusions

A nationwide increase was noted in the number of transplants per year for ALD beginning in 2013, particularly in young and female patients. This comes in the setting of widespread and increasing alcohol use and hospital admissions for ALD.

Research perspectives

Consideration should be given to the use of screening tools aimed at detecting alcohol use in the primary care setting to identify patients with problematic alcohol use and promote reduction in consumption in order to avoid harm.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: This study met expedited review criteria as approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Data sharing statement: Statistical code and dataset available from the corresponding author at lensasi@uw.edu.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

Peer-review started: August 25, 2017

First decision: November 1, 2017

Article in press: December 5, 2017

P- Reviewer: Gad EH, Panduro A, Therapondos G S- Editor: Kong JX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

Contributor Information

Catherine E Kling, Division of Transplant Surgery, Department of Surgery, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, United States.

James D Perkins, Division of Transplant Surgery, Department of Surgery, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, United States.

Robert L Carithers, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, United States.

Dennis M Donovan, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, United States.

Lena Sibulesky, Division of Transplant Surgery, Department of Surgery, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, United States. lensasi@uw.edu.

References

- 1. Available from: https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/view-data-reports/national-data/#.

- 2.Mandayam S, Jamal MM, Morgan TR. Epidemiology of alcoholic liver disease. Semin Liver Dis. 2004;24:217–232. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-832936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruha R, Dvorak K, Petrtyl J. Alcoholic liver disease. World J Hepatol. 2012;4:81–90. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v4.i3.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stickel F, Datz C, Hampe J, Bataller R. Pathophysiology and Management of Alcoholic Liver Disease: Update 2016. Gut Liver. 2017;11:173–188. doi: 10.5009/gnl16477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dwyer-Lindgren L, Flaxman AD, Ng M, Hansen GM, Murray CJ, Mokdad AH. Drinking Patterns in US Counties From 2002 to 2012. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:1120–1127. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rehm J, Taylor B, Mohapatra S, Irving H, Baliunas D, Patra J, Roerecke M. Alcohol as a risk factor for liver cirrhosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010;29:437–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singal AK, Guturu P, Hmoud B, Kuo YF, Salameh H, Wiesner RH. Evolving frequency and outcomes of liver transplantation based on etiology of liver disease. Transplantation. 2013;95:755–760. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31827afb3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quillin RC 3rd, Wilson GC, Sutton JM, Hanseman DJ, Paterno F, Cuffy MC, Paquette IM, Diwan TS, Woodle ES, Abbott DE, Shah SA. Increasing prevalence of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis as an indication for liver transplantation. Surgery. 2014;156:1049–1056. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2014.06.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldberg D, Ditah IC, Saeian K, Lalehzari M, Aronsohn A, Gorospe EC, Charlton M. Changes in the Prevalence of Hepatitis C Virus Infection, Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis, and Alcoholic Liver Disease Among Patients With Cirrhosis or Liver Failure on the Waitlist for Liver Transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1090–1099.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Apparent per capita alcohol consumption: national, state, and regional trends, 1977-2014. Arlington, VA. [accessed 2017 Jun 28] Available from: https://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/surveillance104/CONS14.pdf.

- 11.Guirguis J, Chhatwal J, Dasarathy J, Rivas J, McMichael D, Nagy LE, McCullough AJ, Dasarathy S. Clinical impact of alcohol-related cirrhosis in the next decade: estimates based on current epidemiological trends in the United States. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39:2085–2094. doi: 10.1111/acer.12887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Liver cirrhosis mortality in the United States: national, state and regional trends, 2000-2013. Arlington, VA. [accessed 2017 Jun 28] Available from: https://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/surveillance105/Cirr13.pdf.

- 13.O’Grady JG. Liver transplantation alcohol related liver disease: (deliberately) stirring a hornet’s nest! Gut. 2006;55:1529–1531. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.090506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Julapalli VR, Kramer JR, El-Serag HB; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Evaluation for liver transplantation: adherence to AASLD referral guidelines in a large Veterans Affairs center. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:1370–1378. doi: 10.1002/lt.20434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldberg D, French B, Newcomb C, Liu Q, Sahota G, Wallace AE, Forde KA, Lewis JD, Halpern SD. Patients With Hepatocellular Carcinoma Have Highest Rates of Wait-listing for Liver Transplantation Among Patients With End-Stage Liver Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1638–1646.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murray KF, Carithers RL Jr; AASLD. AASLD practice guidelines: Evaluation of the patient for liver transplantation. Hepatology. 2005;41:1407–1432. doi: 10.1002/hep.20704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin P, DiMartini A, Feng S, Brown R Jr, Fallon M. Evaluation for liver transplantation in adults: 2013 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the American Society of Transplantation. Hepatology. 2014;59:1144–1165. doi: 10.1002/hep.26972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.European Liver Transplant Registry. Specific results by disease. [accessed 2017 Nov 6] Available from: http://www.eltr.org/Specific-results-by-disease.html.

- 19.Fosby B, Melum E, Bjøro K, Bennet W, Rasmussen A, Andersen IM, Castedal M, Olausson M, Wibeck C, Gotlieb M, et al. Liver transplantation in the Nordic countries - An intention to treat and post-transplant analysis from The Nordic Liver Transplant Registry 1982-2013. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:797–808. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2015.1036359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, Keesey J, Hicks J, DeCristofaro A, Kerr EA. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2635–2645. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa022615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.European Association for the Study of Liver. EASL clinical practical guidelines: management of alcoholic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2012;57:399–420. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jonas DE, Garbutt JC, Amick HR, Brown JM, Brownley KA, Council CL, Viera AJ, Wilkins TM, Schwartz CJ, Richmond EM, et al. Behavioral counseling after screening for alcohol misuse in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:645–654. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-9-201211060-00544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friedmann PD. Clinical practice. Alcohol use in adults. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:365–373. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1204714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ewing JA. Detecting alcoholism. The CAGE questionnaire. JAMA. 1984;252:1905–1907. doi: 10.1001/jama.252.14.1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aertgeerts B, Buntinx F, Kester A. The value of the CAGE in screening for alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence in general clinical populations: a diagnostic meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:30–39. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00254-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization. AUDIT. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Care. Geneva, Switzerland. [accessed; 2017. p. Jul 3]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/67205/1/WHO_MSD_MSB_01.6a.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Shea RS, Dasarathy S, McCullough AJ; Practice Guideline Committee of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;51:307–328. doi: 10.1002/hep.23258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saitz R, Cheng DM, Allensworth-Davies D, Winter MR, Smith PC. The ability of single screening questions for unhealthy alcohol and other drug use to identify substance dependence in primary care. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2014;75:153–157. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. Regions. [accessed 2017 Nov 6] Available from: https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/members/regions/