Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to determine whether a modified enhanced recovery after surgery (mERAS) protocol has a positive effect on the recovery of aged patients with esophageal cancer undergoing esophagectomy.

Methods

Consecutive patients were selected between January 2015 and June 2016 and were randomly assigned to a control group (traditional nursing care) or an observation group (mERAS protocol). We analyzed the outcomes of the patients, including surgical outcomes, postoperative complications, mental health status, and quality of life (QOL).

Results

Altogether, 110 patients who were >60 years of age were included in the study. They were evenly divided into two groups, with 55 patients in each. For the observation group, the thoracic drainage time was 1.07±0.26 days, first jejunal feeding time was at 11.71±1.81 h, time of first postoperative flatus was at 12.00±1.75 h, and length of postoperative stay was 8.31±1.25 days. There was no anastomotic leakage in the observation group, and the incidence of postoperative pulmonary infection was 5.45%. All the above indexes in the observation group were better than those for the patients receiving traditional nursing care. In addition, patients in the observation group had a lower level of mental suffering (P<0.05) and higher QOL (P<0.05).

Conclusions

mERAS protocols could result in better postoperative recovery and reduce postoperative complications in aged patients undergoing esophagectomy. Hence, mERAS protocols could be useful in reducing patients’ mental suffering and improving their QOL.

Keywords: Esophageal cancer, modified enhanced recovery after surgery (mERAS), aged patient, mental status, quality of life (QOL)

Introduction

The enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol is an effective method that aims to relieve surgical stress, reduce surgery-related complications, and enhance postoperative recovery during the perioperative period. The ERAS protocol has been successfully implemented in patients with various surgically treated diseases, especially following colorectal surgery (1-3).

Esophageal cancer is a common malignancy in China, and esophagectomy is associated with a high incidence of postoperative complications. Few studies, however, reported the use of this protocol in patients undergoing esophagectomy. In recent years, based on previous reports and our own experience, we have modified the ERAS protocol in many aspects for aged patients who are physically weaker and at more risk than younger patients when undergoing surgery. Also, their postoperative quality of life (QOL) is expected to be poor.

This prospective randomized controlled study aimed to analyze the short-term outcomes, QOL after survival, and the mental status of aged patients with esophageal cancer who underwent esophagectomy and postoperative care with our modified enhanced recovery after surgery (mERAS) protocol. The goal was to study the feasibility and application of the mERAS protocol for nursing management of aged patients who undergo esophagectomy.

Methods

Patient recruitment

A total of 110 aged patients (defined as >60 years of age according to the Asia-Pacific classification) who underwent esophagectomy in the Thoracic Department of Fujian Medical University Union Hospital from January 2015 to June 2016 were randomly divided into two groups of 55 patients each: an observation group (treated with the mERAS protocol) and a control group (with conventional nursing care). Inclusion criteria included (I) age >60 years; (II) esophageal squamous cell carcinoma diagnosed pathologically on preoperative biopsy; (III) preoperative medical examinations—e.g., thoracic and upper abdominal enhanced computed tomography—that showed no evidence of apparent tumor invasion or distant metastasis; (IV) pulmonary and cardiac function examinations indicating that the patient was able to tolerate the surgery; (V) minimally invasive esophagectomy was performed. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (I) an illiterate patient or one who was unable to communicate; (II) adjuvant therapy was applied; (III) presence of a malignant tumor within the previous 5 years; (IV) presence of serious preoperative complications; (V) conventional thoracotomy was performed. All operations were performed by experienced surgeons in our department. The institutional review board of Fujian Medical University Union Hospital, China, approved the study.

Nursing methods

The mERAS protocol in our study was based on protocols described for patients who had undergone colonic surgery or esophagectomy in reported studies and in our own previous experience.

Control group

The general nursing routine for esophageal surgery was used for the postoperative care of the control patients. It focuses on the following points.

Preoperative nursing: (I) respiratory tract preparation: no smoking for at least 2 weeks prior to surgery; atomization twice a day during the preoperative period; correct instructions about back-slapping and effective cough and sputum production. (II) Bowel preparation: perform a clean enema 1 day preoperatively; food-fast for 12 h; liquid-fast for 8 h.

Postoperative nursing: (I) monitor vital signs: heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation. At 6 h after vital signs remain stable, elevate the head of bed 30°. (II) Maintain airway patency. (III) Maintain pipeline patency: avoid curling and slipping; pay extra attention while caring for chest closed drainage, monitoring the amount, character, and color of the shunt fluid. (IV) Intestinal nutrition: initially commence constant injection of 5% glucose and sodium chloride (GNS) until 500 mL through a jejunal stoma after postoperative flatus. Then, replace GNS with total parenteral nutrition (TPN), such as Peptison and Nutrison (both: Nutricia, Dublin, Ireland). In both groups, postoperative nutrition supply (including calorie and protein supply) was comparable. Calorie intake requirements are 20–25 kcal/kg/d during stress including 1.2 to 1.5 g/kg/d of protein enterally or 0.25 to 0.30 g of nitrogen/kg/d parenterally. An average intake of 1,500 kcal/d is recommended.

Observation group

For the observational group, in addition to the postoperative general nursing routine after esophageal surgery, we conducted an ERAS ideas-guided nursing plan.

Preoperative nursing: this protocol included the following activities. (I) Mental nursing: educate the patient about the hospitalization and offer preoperative direction. Inform the patients and their family members of the content of ERAS; make sure they fully understood the relevant information and the entire therapeutic process. We played videos related to the surgery, providing direct perception of the entire process, from the ward to operation room, surgical operation, postanesthesia care unit, and finally back to the ward, with the purpose of relieving their stress and fear. (II) Central catheter, peripherally inserted: the catheter was routinely applied preoperatively in preparation for venous nutrition both before and after the operation. (III) Preoperative nutrition evaluation: we evaluated the patient’s nutritional status using the abridged Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment. For malnourished patients, TPN (Kabiven™; Fresenius Kabi AG, Homburg, Germany) was dripped in through the peripherally inserted central catheter to reverse the malnutrition. (IV) Preoperative intestinal preparation: the patient was given an intestinal cleansing agent, which was ingested orally on the afternoon of the day before surgery as a clean enema (a cleansing enema is forbidden). The patient food fasts for 6 h before surgery and liquid-fasts for 4 h.

Intraoperative nursing: in the observation group, the Bair Hugger Normothermia System (3M Bair Hugger, www.bairhugger.com) and warmed intravenous fluid were used to prevent hypothermia during the operation. Pneumatic compression stockings were also used in the observation group, which was not standard protocol in the control group.

Postoperative nursing: in addition to the general postoperative nursing routine, the following must be given extra attention. (I) Keep the patient warm after surgery by maintaining the temperature of the ward room at 24–26 °C; (II) apply the pneumatic pump to knead the lower limbs 6 h postoperatively while the vital signs are stable. Active limb exercises on the bed are encouraged as they could prevent the formation of deep venous thrombosis; (III) provide effective analgesia after surgery; (IV) encourage early ambulation. Therefore, on postoperative day (POD) 1, the patient is helped to sit on the bedside, with the lower limbs hanging down. On POD 2 the patient is helped to stand near the bed and on POD 3 to walk beside bed, step by step. We encourage POD1 or POD2 ambulation, if the patient recovered well; (V) provide early enteral nutrition. We started enteral nutrition through a jejunal tube 6–12 h postoperatively to promote intestinal peristalsis. It is begun with 5% GNS 500 mL and, when the patient shows no abdominal distention or diarrhea, switched to TPN (e.g., Peptison, Nutrison). We calculated the postoperative calorie and protein supply for every patient in observation group with the same guideline with the control group; (VI) on POD 1, remove the earlier inserted tubes, urethral catheter, and drainage tube; (VII) after POD 3, instruct the patients to practice chewing and swallowing to prevent a deglutition disorder and choking when swallowing Urografin for the gastrointestinal imaging examination; (VIII) for the control group, on POD 7, after esophageal radiography shows no leakage, routinely encourage the patients to start oral feeding. If the intake is good, the nasogastric tubes are removed, and the patient is discharged from the hospital.

In the observation group, after cervicothoracic computed tomography showed no leakage on POD 7, the nasogastric tubes were removed, and the patients were discharged from the hospital. We prolonged oral fasting time, until esophageal radiography (performed on PODs 10–14) confirmed that there were no signs of leakage. With that confirmation, the patients were encouraged to start oral feeding.

Surgical procedures and techniques

All of the patients received thoracoscopic and laparoscopic minimally invasive esophagectomy. We did the skeletonization of recurrent laryngeal nerves (RLN) and en bloc resection of the para-nerve lymph nodes and soft tissues, using esophageal suspension method, of which we had reported the feasibility and safety in extensive thoracoscopic lymphadenectomy along the RLN in the semi-prone position (4). We commonly used the gastric tube to do the reconstruction. We commonly did the 2-field lymph node dissection. If the preoperative examinations showed possible metastatic supraclavicular lymph nodes, the tumor located in the upper segment of esophagus or intraoperative frozen pathological results showed positive right RLN lymph node, we would do the 3-field lymph node dissection. Patients were extubated immediately after the operation or on arrival in the ward of intensive care unit.

Discharge criteria

Discharge criteria in both groups included adequate pain control with or without oral analgesics, absence of nausea, adequate calorie intake (orally or via enteral catheter), passage of flatus and/or stool, self-mobilization, self-support and patient’s consent.

Clinical outcomes

We analyzed the patients’ characteristics: including age, sex, preoperative complications, tumor location, and pathological staging. We analyzed surgery-related indicators, such as drainage duration, time of first postoperative flatus, frequency of sputum suction with a fiberbronchoscope, length of hospital stay, pulmonary infection, and anastomotic leakage. And the criteria for removing thoracic drain included re-expand of the lung, drainage volume less than 150 mL/day, no bloody or chylous-like drainage, adequate control of pneumonia, absence of massive pleural effusion. The presence of pneumonia is defined by new lung infiltrate plus clinical evidence that the infiltrate is of an infectious origin (5,6). The criteria for sputum suction included lack of effective cough, thick and heavy sputum, atelectasis showed by X-rays or CT images.

We analyzed the patients’ postoperative QOL using the scale established by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC QLQ-C30 V3.0, Chinese Version) (7). Their mental status was assessed using the National Comprehensive Cancer Network-recommended Distress Thermometer (8). A self-evaluation of mental distress, this tool includes 11 items that are scored on a scale ranging from 0 to 10, where 0= no stress and 10= extreme stress.

Statistical analyses

SPSS 20.0 statistics software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for the analyses. Normally distributed quantitative data with equal variance were analyzed using an independent t-test. The Mann-Whitney test was used for data that were not normally distributed or did not have equal variance. The t-test was used to compare the means of two samples. The χ2 test was used to make comparisons between qualitative data. Comparisons among groups of repeatedly measured data required multivariate analysis of variance. A value of P<0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

Patient characteristics and clinical features

A prospective cohort design was used to observe 110 aged patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. There were 55 patients in the observation group (38 men, 17 women; mean ± SD age 67.73±6.69 years; range, 60–86 years) and 55 patients in control group (41 men, 14 women; mean ± SD age 67.00±5.58 years; range 60–85 years). We used Onodera’s prognostic nutritional index (PNI) to evaluate the preoperative nutrition status, which is calculated from baseline clinical parameters, namely, peripheral lymphocyte count and serum albumin (9,10). There was no significant difference in age, sex, preoperative complications, tumor location, PNI value or pathological staging between the two groups (P>0.05). The patients’ characteristics and clinical features are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Comparison of the patient characteristics and clinical features between observation group and control group.

| Items | Observation group (n=55) | Control group (n=55) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years old) | 67.73±6.69 | 67.00±5.58 | 0.537 |

| Gender | 0.525 | ||

| Male | 38 | 41 | |

| Female | 17 | 14 | |

| Complications | 0.409 | ||

| Positive | 19 | 15 | |

| Negative | 36 | 40 | |

| Tumor location | 0.561 | ||

| Upper | 9 | 7 | |

| Middle | 32 | 29 | |

| Lower | 14 | 19 | |

| PNI value | 0.569 | ||

| ≤45 | 28 | 25 | |

| >45 | 27 | 30 | |

| Pathological staging | 0.130 | ||

| I–II | 44 | 37 | |

| III | 11 | 18 | |

PNI, prognostic nutritional index.

Postoperative clinical outcomes

An independent sample t-test, nonparametric test, or χ2 test was used to define whether there were statistical significances in the postoperative clinical outcomes between the two groups. The results showed significant differences in the duration of thoracic drainage, length of hospital stay, frequency of sputum suction, incidence of pulmonary infection, and incidence of anastomotic leakage (all P<0.05). The times of first flatus and jejunal feeding were earlier in the observation group than the control group. Surgical clinical outcomes are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Comparison of surgical features and main complications between observation group and control group.

| Surgical outcomes | Observation group (n=55) | Control group (n=55) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time of thoracic drainage (hours) | 48.07±0.26 | 76.27±4.75 | 0.011 |

| Time of postoperative hospital stay (days) | 8.31±1.25 | 13.72±1.63 | 0.042 |

| Mean frequency of sputum suction (times) | 1.09±0.35 | 4.16±0.66 | 0.027 |

| Pulmonary infection | 0.013 | ||

| Positive | 3 | 12 | |

| Negative | 52 | 43 | |

| Misinhalation | 0.052 | ||

| Positive | 1 | 6 | |

| Negative | 54 | 49 | |

| Anastomotic leakage | 0.012 | ||

| Positive | 0 | 6 | |

| Negative | 55 | 49 | |

| Time of jejunum feeding (hours) | 11.73±1.81 | 21.16±2.51 | 0.023 |

| Time of first postoperative flatus (hours) | 11.80±1.77 | 19.16±2.51 | 0.031 |

Preoperative and postoperative QOL

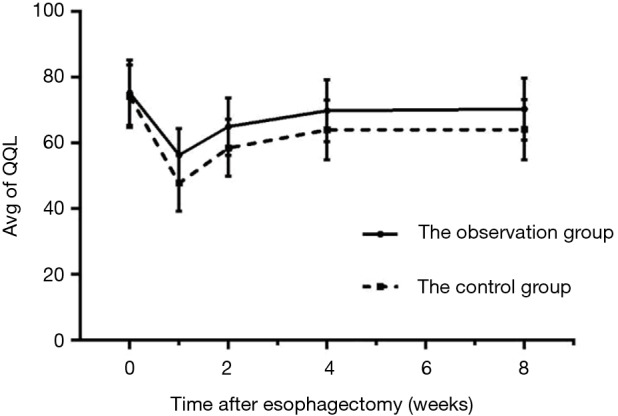

As shown in Table 3 and Figure 1, the QOL scores of both groups fell during postoperative week (POW) 1 and then increased during POW 2, reaching a relatively stable condition during POWs 4–8, although they were still lower than the preoperative QOL score. Because the QOLs of different periods comprised qualitative data measured repeatedly, a multivariate analysis of variance was used to conduct the analyses, which indicated no statistical difference in the preoperative QOL between the two groups (P>0.05). In contrast, the QOL was statistically significantly higher in the observation group than in the controls at POWs 1, 2, 4, and 8 (P<0.05).

Table 3. Comparison of pre- and post-operative QOL between observation group and control group.

| QOL | Observation group (n=55) | Control group (n=55) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-operativeD1 | 75.33±9.97 | 74.24±9.55 | 0.559 |

| POW 1 | 56.40±7.99 | 47.78±8.54 | 0.028 |

| POW 2 | 65.07±8.82 | 58.56±8.69 | 0.033 |

| POW 4 | 69.89±9.41 | 64.05±9.08 | 0.014 |

| POW 8 | 70.36±9.44 | 64.09±9.19 | 0.011 |

QOL, quality of life; POW, postoperative week.

Figure 1.

Trends of pre- and post- operative QOL of observation group and control group. QOL, quality of life.

Preoperative and postoperative mental distress

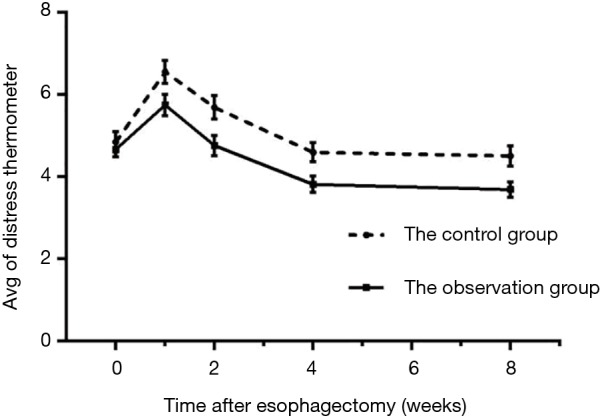

The mental stress of both groups increased during POW 1 and then decreased at POW 2, finally reaching a relatively stable condition during POWs 4–8, although it was still lower than that preoperatively (Table 4, Figure 2). Because mental stress was measured as qualitative data and was determined repeatedly, multivariate analysis of variance was used to conduct the analysis. It indicated no statistical difference in preoperative mental stress between the two groups (P>0.05), whereas the mental stress of the observation group was significantly lower than that of the controls at POWs 1, 2, 4, and 8 (P<0.05).

Table 4. Comparison of pre- and post-operative mental stress between observation group and control group.

| Mental stress | mERAS (n=55) | Traditional recovery (n=55) | F value | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-operative D1 | 4.85±1.86 | 4.67±1.31 | 0.593 | 0.554 |

| POW 1 | 6.56±2.05 | 5.75±1.90 | 2.171 | 0.032 |

| POW 2 | 5.69±2.12 | 4.76±1.89 | 2.421 | 0.017 |

| POW 4 | 4.60±1.81 | 3.82±1.50 | 2.462 | 0.015 |

| POW 8 | 4.51±1.83 | 3.69±1.41 | 2.621 | 0.010 |

POW, postoperative week.

Figure 2.

Trends of pre- and post-operative mental stress of observation group and control group.

Discussion

With the increasing development of the economy, science, and technology in China, the average life expectancy of the Chinese population is also increasing—as is the incidence of esophageal cancer (11). Although the prognosis of esophageal cancer treatment is relatively poor, most aged patients still choose surgery. Esophagectomy is associated with a high rate of postoperative complications, especially in aged patients. In recent years, the idea of fast-track surgery, which reduces surgical stress and enhances recovery of organ function, is gradually being applied to perioperative care of esophageal cancer patients. Adoption of fast-track protocols can reduce the surgical trauma and lighten the postoperative stress response to some extent (12,13). Aged patients, with their weaker bodies, usually experience more complications. They may also have poor postoperative recovery. We have modified our ERAS protocols in many aspects. We conducted this study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of mERAS protocols in aged patients who underwent esophagectomy by observing the postoperative clinical outcomes, QOL, and psychological status of the two groups during POWs 1–8.

The results of this study showed that the postoperative thoracic drainage time and hospital stay of the observation group were significantly shorter than those of the control group, similar to the results of Preston et al. and Munitiz et al. (13,14). In addition, the incidence of pulmonary infections and anastomotic leakage, and the frequency of sputum suctioning, were lower than in the control group. We believe that the main reason for these differences between the two groups was application of the mERAS protocol.

Our reasoning is as follows: (I) shortening the preoperative food and drink fasting times greatly relieves patient discomfort (e.g., thirst, irritability, anxiety). It also reduces the adverse effects caused by prolonged fasting and reduces the stress response of patients to the operation; (II) we did not perform a cleansing enema for preoperative bowel preparation in the traditional way. The new bowel preparation could reduce the changes in the patients’ physiological environment, which can reduce intestinal damage, increase patient comfort, and reduce the stress response; (III) early postoperative extubation can promote early ambulation, thereby allowing early removal of drainage tubes and avoiding a variety of uncomfortable stimuli caused by the tubes; (IV) the use of a pneumatic pump and early ambulation postoperatively promotes lung function and tissue oxidation capacity and reduces venous stasis and thrombosis (15); (V) adequate early enteral nutrition after operation is a prerequisite for rapid rehabilitation. It is beneficial to the patient’s physiological state and could reduce the occurrence of anastomotic leakage and other complications (16). It also reduces the need for intravenous fluids, the volume of which may be associated with pulmonary and cardiac complications.

Our results showed significantly decreased incidence of anastomotic leakage in the mERAS intervention group, which was an outstanding result. We believed that the low incidence was the result of systematic project. It may associated with the preoperative mental nursing, evaluation of nutritional status, prevention of hyperthermia, protocols to prevent formation of thrombosis, early postoperative ambulation, early enteral nutrition support, prolonged fasting time, our modified surgical techniques and so on.

QOL has become an important concern regarding treatment options and long-term efficacy (17). This study shows that the QOL of the two groups had decreased significantly at POW 1 and gradually increased during POW 2, remaining relative steady during POWs 4–8, although it was still lower than that preoperatively. In addition, the QOL scores at POWs 1, 2, 4, and 8 were higher in the observation group than in the control group (P<0.05), which was largely related to the recovery status of the patient’s postoperative physical, psychological, and social conditions.

Psychological distress is a result of the patient's emotional experiences brought on by a variety of factors. These emotional experiences could have an adverse effect on the cancer, physical symptoms, and the treatment (18). The psychological distress of the patients in the two groups in this study increased significantly at POW 1, then gradually decreased during POW 2, attaining a relatively steady state at POWs 4–8, although it was still higher than that preoperatively. The psychological distress of patients in the observation group was much lower than that of the controls at POWs 1, 2, 4, and 8 (P<0.05). The reason for this difference may be that, under normal circumstances, although patients often experience psychological distress because of the tumor itself and the side effects of the treatment (19), elderly patients with esophageal cancer who undergo surgery are more prone to fear and uneasiness because they do not have the relevant knowledge about the operation. In addition, the patient's physical distress and discomfort at POW 1 are more serious because of their age and a more difficult physical recovery although their psychological fear and distress have gradually declined. In contrast, the patients in the observation group had a less severe postoperative stress reaction because of their preoperative education. In addition, the degree of their psychological distress was lower than that of those in the control group.

Application of mERAS protocols to perioperative nursing care in aged patients who undergo esophagectomy could reduce the incidence of postoperative complications. It could also relieve patients’ psychological distress and improve their QOL.

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to express our sincere appreciation to Dr. Yong Zhu for his valuable comments on our study. We thank Nancy Schatken, BS, MT (ASCP), from Liwen Bianji, Edanz Group China, for editing the English text of a draft of this manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Science and Technology Key Project of Fujian Province, China (grant number: 2014Y0024) and Fujian Province Health Education Joint Plan Project (grant number: WKJ2016-2-09).

Ethical Statement: Our study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Fujian Medical University Union Hospital (No. 2015KY025), and all the participants agreed to participate in this study.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Kehlet H, Wilmore DW. Multimodal strategies to improve surgical outcome. Am J Surg 2002;183:630-41. 10.1016/S0002-9610(02)00866-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nanavati AJ, Prabhakar S. Fast-track surgery: toward comprehensive peri-operative care. Anesth Essays Res 2014;8:127-33. 10.4103/0259-1162.134474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lau CS, Chamberlain RS. Enhanced recovery after surgery programs improve patient outcomes and recovery: a meta-analysis. World J Surg 2017;41:899-913. 10.1007/s00268-016-3807-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zheng W, Zhu Y, Guo CH, et al. Esophageal suspension method in scavenging peripheral lymph nodes of the left recurrent laryngeal nerve in thoracic esophageal carcinoma through semi-prone-position thoracoscopy. J Cancer Res Ther 2014;10:985-90. 10.4103/0973-1482.144354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Low DE, Alderson D, Cecconello I, et al. International consensus on standardization of data collection for complications associated with esophagectomy: esophagectomy complications consensus group (ECCG). Ann Surg 2015;262:286-94. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Thoracic Society, Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, wentilator-associated, and helathcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:388-416. 10.1164/rccm.200405-644ST [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Snyder CF, Blackford AL, Sussman J, et al. Identifying changes in scores on the EORTC-QLQ-C30 representing a change in patients’ supportive care needs. Qual Life Res 2015;24:1207-16. 10.1007/s11136-014-0853-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tavernier SS. Translating research on the distress thermometer into practice. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2014;18 Suppl:26-30. 10.1188/14.CJON.S1.26-30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanda M, Fujii T, Kodera Y, et al. Nutritional predictors of postoperative outcome in pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg 2011;98:268-74. 10.1002/bjs.7305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sakurai K, Ohira M, Tamura T, et al. Predictive protential of preoperative nutritional status in long-term outcome projections for patients with gastic cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2016;23:525-33. 10.1245/s10434-015-4814-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Torre LA, Sieqel RL, Ward EM, et al. Global cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends – an update. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2016;25:16-27. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blom RL, van Heijl M, Bemelman WA, et al. Initial experiences of an enhanced recovery protocol in esophageal surgery. World J surg 2013;37:2372-8. 10.1007/s00268-013-2135-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Preston SR, Markar SR, Baker CR, et al. Impact of a multidisciplinary standardized clinical pathway on perioperative outcomes in patients with oesophageal cacner. Br J Surg 2013;100:105-12. 10.1002/bjs.8974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Munitiz V, Martinez-de-Haro LF, Ortiz A, et al. Effectiveness of a written clinical pathway for enhanced recovery after transthoracic (Ivor Lewis) oesophagectomy. Br J Surg 2010;97:714-8. 10.1002/bjs.6942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Z, Tao X, Chen Y, et al. Bed rest versus early ambulation with standard anticoagulation in the management of deep vein thrombosis: a meta-analysis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0121388. 10.1371/journal.pone.0121388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang S, Wu X, Yu W, et al. Early enteral nutrition in critically ill patients with hemodynamic instablity: an evidence-based review and practical advice. Nutr Clin Pract 2014;29:90-6. 10.1177/0884533613516167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamel JF, Saulnier P, Pe M, et al. A systematic review of the quality of statistical methods employed for analysing quality of life data in cancer randomized controlled trials. Eur J Cancer 2017;83:166-76. 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.06.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uqalde A, Haynes K, Boltong A, et al. Self-guided interventions for managing psychological distress in people with cancer – a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 2017;100:846-57. 10.1016/j.pec.2016.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Belcher SM, Hausmann EA, Cohen SM, et al. Examining the relationship between multiple primary cancers and psychological distress: a review of current literature. Psychooncology 2017;26:2030-9. 10.1002/pon.4299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]