Abstract

Malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) is an aggressive tumor and the prognosis is still dismal despite the various proposed multimodal treatment plans. Currently, new palliative treatments, such as talc pleurodesis, are being explored besides traditional surgery. This review reports survival rates after talc pleurodesis in comparison to surgery in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma. A systematic literature search yielded 49 articles eligible for this review. The mean survival in the talc pleurodesis group was 14 months compared to 17 and 24 months for the pleurectomy decortication (P/D) group and extrapleural pneumonectomy (EPP) group, respectively. Few studies reported on the 1-, 2-year overall survival for the talc pleurodesis group and the results were very heterogeneous. The pooled 1-year overall survival for the P/D and EPP groups were 55% [credibility limits (CL): 21–87%] and 67% (CL: 3–89%), the pooled 2-year overall survival were 32% (CL: 8–63%) and 36% (CL: 8–54%), respectively. The pooled 1- and 2-year survival for surgery independently from the type of surgery were 62% (CL: 38–84%) and 34% (CL: 16–54%). There was significant heterogeneity in all the analyses. This review shows that there is limited research on the survival rate after talc pleurodesis compared to surgery in the treatment of malignant pleural mesothelioma. A comparison study is necessary to accurately assess the best way to treat MPM patients, including assessment of the quality of life after treatment as an outcome measure.

Keywords: Pleural cancer, extrapleural pneumonectomy (EPP), pleurectomy decortication (P/D), comparative effectiveness

Introduction

Malignant mesothelioma is a rare disease with an average of 2,000 to 3,000 new cases per year in the United States. Although malignant mesothelioma has been known as a clinical entity since 1947, the link with asbestos exposure was only established in 1960 when an epidemic was reported among asbestos miners. In the past century, asbestos has been widely used in construction and insulation because of its fire-resistant properties. Although western countries have banned its use for several decades, asbestos exposure is still a present threat because of its presence in old building and constructions, and because of the long mesothelioma latency period (1). The most common form is malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) accounting for 70% of all mesothelioma cases. The prognosis of MPM is still dismal despite the various proposed multimodal treatment plans (1). Because MPM is an aggressive tumor with a poor prognosis, finding the best treatment option is critical. Therapeutic approaches include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation and a combination of the above. Surgery still is the cornerstone in the treatment of MPM. The most important surgical strategies are extrapleural pneumonectomy (EPP) and radical pleurectomy decortication (P/D) (2). Both surgeries have a beneficial role in alleviating symptoms (2). A recent meta-analysis concluded that the short-term mortality was significantly higher in the EPP group compared to the P/D group (3).

Currently, new palliative treatments, such as talc pleurodesis, are being explored. Talc pleurodesis has been used in the treatment of malignant pleural effusion (MPE), a common complication of advanced malignancies especially breast and lung cancer (4). Talc is distributed over the entire pleural surface by administering it as a dry powder, usually during thoracoscopy, or as slurry via a chest tube (5). Thoracoscopic talc poudrage showed to be an effective and safe procedure in patients with MPE with a high rate of successful pleurodesis and a positive effect on decreasing dyspnea (4).

To date, there has been limited research on the use of talc pleurodesis and only one randomized clinical trial directly compared talc pleurodesis with video-assisted thoracoscopic partial pleurectomy (VAT-PP) (6). Therefore, we performed a comprehensive review to compare survival rates between surgery and talc pleurodesis in patients with MPM.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

Original research studies that evaluated survival after surgical interventions or talc pleurodesis in the treatment of MPM were identified by searching the National Library of Medicine and National Institutes of Health PubMed database through June 2016. The search strategy included the following keywords: “mesothelioma”, “malignant pleural mesothelioma”, “talc pleurodesis”, “pleurectomy” and “pneumonectomy”. Reference lists from all retrieved articles, including the reference lists of previously published reviews on the treatment of MPM, were also reviewed in search of additional eligible articles. Original research published between 1990 and 2016 was included.

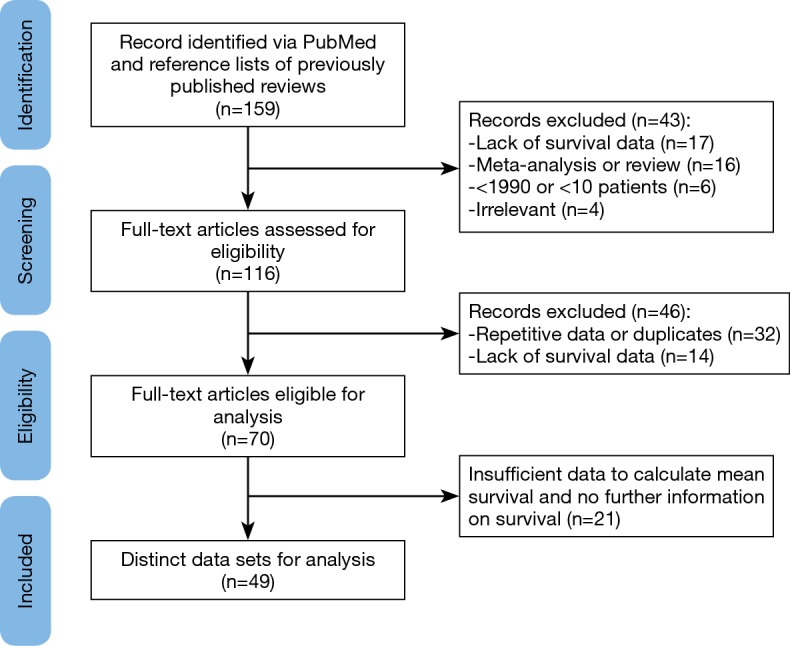

Studies were considered eligible if they met the following inclusion criteria (Figure 1) (1): MPM patients who underwent either talc pleurodesis-including video-assisted thoracoscopic (VAT), pleurodesis with talc poudrage, thoracoscopic talc poudrage, talc slurry via chest tube, and tube thoracostomy with talc pleurodesis- or surgical resection-including EPP, pleuro-pericardium-pneumonectomy, P/D, and pleurectomy (2); data on survival were provided or could be extrapolated from published results (3); studies included at least ten patients (4); studies were written in English. Studies were excluded based on the following reasons: (I) meta-analyses or reviews; (II) lack of key information for calculation of survival; (III) repetitive data or duplicates. When multiple studies were published using the same group of patients, only the study with the largest number of patients and the most complete data was included.

Figure 1.

Article selection process-PRISMA graph.

Data extraction

All relevant characteristics were extracted from the studies including author, publication year, number of patients, mean age, gender, histology, treatment, survival. Several studies reported survival for multiple types of surgery. The results from each surgical group were imputed separately and the type of surgery was specified if possible. The primary outcome of the study was survival including mean survival, 1-, and 2-year percent survival.

Data analysis and statistical analysis

Median and mean survival in months were extracted from each study. When the median survival was reported in days, the value was divided by 30.5 to convert it to months. Median survival times were converted to mean survival times with an estimation of the standard deviation from the ranges provided (7).

R 3.3.1 and R Studio version 0.99.902 were used to statistically combine the results of individual studies and to produce a summary estimate that takes into account the weight (size) of each study. The combined percent survival was calculated using random effect models. Heterogeneity was tested using the Q statistics and the I2 statistics. The I2 statistic was used as a confirmatory test for heterogeneity with I2 <25%, 25 to 50% and >50% representing a low, moderate and high degree of heterogeneity, respectively (8,9).

Results

Search results

The PubMed search yielded 159 articles which were screened by title and abstract (MM). This resulted in the exclusion of reviews and meta-analyses (n=16), articles lacking survival data (n=17) or specific MPM treatment (n=4) and articles older than 1990 or with less than 10 study participants (n=6). The remaining 116 articles were fully reviewed by two independent reviewers (MM; MvG), resulting in the exclusion of another 46 articles; 14 articles lacked percent survival or survival time and 32 articles had repetitive data or were duplicates of already included articles. When the two researchers did not come to an agreement on whether or not to include or exclude an article, a third researcher was consulted (ET). Of the 70 articles eligible for analysis, 21 articles had insufficient data to calculate survival and were therefore excluded (Figure 1). The remaining 49 articles were included in the analysis and provided 70 different patient treatment groups (Table 1). These datasets were assigned to the “talc”, “EPP”, “P/D” or “surgery unspecified” group independently from any additional treatment. Because mesothelioma has a low survival rate, most patients undergo additional treatments such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy. We therefore assumed that most patients received other treatments besides surgery of talc pleurodesis which justifies grouping these different datasets together independently from the additional treatment status.

Table 1. Description of included studies.

| Author year | n | Male (%) | Mean age (years) | Histology | Treatment | Mean survival (months) | 1-year OS (%) | 2-year OS (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Talc pleurodesis | ||||||||

| Phillips 2003 (10) | 40 | 70 | 68.4 | Epithelioid 68%; sarcomatous 7%; biphasic 25% | VAT talc pleurodesis | – | 17.5 | 10 |

| Aelony 2005 (11) | 26 | 88 | 68 | Epithelial 88%; sarcomatoid 12% | TTP | 27.4 | – | – |

| Ak 2009 (12) | 26 | N/A | 63 | Epithelial 73%; sarcomatous 12%; unidentified 15% | TTP | 12 | – | – |

| Rintoul 2014 (6) | 88/73# | 86 | 69.4 | Epithelioid 83%; sarcomatoid 8%; biphasic 9% | Talc pleurodesis | 13.85 | 57 | – |

| Rena 2015 (13) | 172 | 73 | 68.5 | Epithelioid 72%; biphasic 17%; other 11% | VAT talc pleurodesis | – | – | 13@ |

| Mean age/survival | – | – | 67.46 | – | – | 14 | – | – |

| P/D | ||||||||

| Sauter 1995 (14) | 20 | 85 | 66.3 | Epithelial 50%; sarcomatoid 30%; mixed 20% | P/D | – | – | 25 |

| Sauter 1995 (14) | 20/13# | 85 | 66.3 | Epithelial 50%; sarcomatoid 30%; mixed 20% | P/D + CT* | – | – | 15 |

| Soysal 1997 (15) | 100 | 83 | 41 | Epithelial 60%; sarcomatous 11%; mixed 29% | P/D | 25 | – | – |

| Martin-Ucar 2001 (16) | 51 | 92 | 62.5 | Epithelial 67%; mixed 17%; sarcomatous 16% | Palliative pleurectomy | – | 31 | – |

| Ceresoli 2001 (17) | 121/38# | 79 | 59.8 | Epithelial 73%; sarcomatous 17%; mixed 10% | P/D | – | 50 | – |

| Ceresoli 2001 (17) | 121/16# | 79 | 59.8 | Epithelial 73%; sarcomatous 17%; mixed 10% | P/D + CT* | – | 62.5 | – |

| Takagi 2001 (18) | 189/69# | 81 | 55 | Epithelial 55%; sarcomatous 15%; mixed 24%; unknown 6% | P/D | – | – | 26.1 |

| Lee 2002 (19) | 26 | 81 | 68 | Epithelial 73%; mixed 19%; sarcomatous 4%; undetermined 4% | P/D | – | 64.4 | 32.2 |

| Phillips 2003 (10) | 15 | 87 | 62.2 | Epithelioid 80%; biphasic 13%; sarcomatous 7% | P/D | – | 53.5 | 40 |

| Halstead 2005 (20) | 51 | 86 | 64 | Epithelial 59%; other 41% | P/D | 14 | – | – |

| Martin-Ucar 2007 (21) | 12 | 100 | 61.8 | Epithelial 83%; biphasic 17% | P/D | – | 55 | – |

| Nakas, Trousse 2008 (22) | 51 | 90 | 62 | Epithelioid 78%; biphasic 14%; sarcomatoid 8% | Radical P/D | 15.3 | 53 | 41 |

| Nakas, Trousse 2008 (22) | 51 | 92 | 63 | Epithelioid 55%; biphasic 23%; sarcomatoid 22% | Tumor decortication | 15.3 | 32 | 9.6 |

| Schipper 2008 (23) | 285/34# | 83 | 62.3 | Epithelial 47%; sarcomatous 14%; biphasic 14%; desmoplastic 10%; undetermined 8% | P/D (total) | – | 80 | 35 |

| Schipper 2008 (23) | 285/10# | 83 | 62.3 | Epithelial 47%; sarcomatous 14%; biphasic 14%; desmoplastic 10%; undetermined 8% | P/D (subtotal) | – | 30 | 15 |

| Luckraz 2010 (24) | 34 | 88 | 63.5 | Epithelial 38% | P/D | – | – | 9 |

| Luckraz 2010 (24) | 13 | 100 | 59.4 | Epithelial 62% | P/D + CT | – | – | 29 |

| Luckraz 2010 (24) | 19 | 89 | 60.2 | Epithelial 53% | P/D + RT | – | – | 24 |

| Luckraz 2010 (24) | 24 | 67 | 58.2 | Epithelial 64% | P/D + CT + RT | – | – | 55 |

| Bölükbas 2011 (25) | 35 | 83 | 65 | Epithelial 77%; sarcomatoid 9%; biphasic 14% | P/D | – | 69 | 50 |

| Nakas 2012 (26) | 165/67# | 84 | 60.7 | Epithelial 78%; biphasic 22% | Total pleurectomy | – | 52 | 28 |

| Friedberg 2012 (27) | 38 | 74 | 63.3 | Epithelial 53%; non-epithelial 11%; undetermined 36% | P/D | – | – | 52 |

| Rintoul 2014 (6) | 87 | 86 | 69.5 | Epithelioid 84%; sarcomatoid 11%; biphasic 5% | VAT–PP | 13.65 | 52 | – |

| Nakas 2014 (28) | 140 | 87 | 59 | Epithelioid 76%; biphasic 24% | P/D | – | 60 | 31 |

| Bovolato 2014 (29) | 202 | 74 | 60.5 | Epithelial 77%; biphasic 20.9%; sarcomatoid 2.1%; unknown 5.4% | P/D | – | – | 40 |

| Lang-Lazdunski 2015 (30) | 102 | 79 | 60.6 | Epithelioid 71%; biphasic 25%; sarcomatoid 4% | P/D | – | 87.2 | 62.9 |

| Mean age/survival | – | – | 60.92 | – | – | 17 | 52 | 32 |

| EPP | ||||||||

| DaValle 1994 (31) | 40 | N/A | N/A | Epithelial 65%; mixed 25%; sarcomatous 10% | EPP | 27.53 | 53 | 23 |

| Baldini 1997 (32) | 49 | 76 | 51.5 | Epithelial 71%; sarcomatoid 6%; mixed 22% | EPP | 27 | – | – |

| Takagi 2001 (18) | 189/108# | 81 | 55 | Epithelial 55%; sarcomatous 15%; mixed 24%; unknown 6% | EPP | – | – | 29.7 |

| Aziz 2002 (33) | 302/13# | 71 | 56.3 | Epithelial 54%; fibrosarcomatous 35% Mixed 11% | EPP–CT | 12.25 | 49 | – |

| Aziz 2002 (33) | 302/51# | 71 | 56.3 | Epithelial 54%; fibrosarcomatous 35%; mixed 11% | EPP + CT | 35.25 | 84 | – |

| Ahamad 2003 (34) | 28 | 93 | 58.6 | Epithelioid 79%; biphasic 14%; sarcomatoid 7% | EPP | – | 65 | 49 |

| Edwards 2006 (35) | 92 | 89 | 55.5 | Epithelioid 77%; non-epithelioid 23% | EPP | – | 59 | 34 |

| Pagan 2006 (36) | 42 | 88 | 62 | N/A | EPP | – | – | 38 |

| Martin-Ucar 2007 (21) | 45 | 82 | 50 | Epithelial 71%; biphasic 29% | EPP | – | 53 | – |

| Rea 2007 (37) | 21/17# | 67 | 55.8 | Epithelial 95%; mixed 5% | EPP | – | 82 | 59 |

| Rice 2007 (38) | 100 | 86 | 60 | Epithelioid 67%; biphasic 24%; sarcomatoid 9% | EPP | – | – | 26 |

| van Sandick 2008 (39) | 15 | 87 | 57.8 | Epithelial 93%; mixed 7% | EPP | 30.5 | – | – |

| Aigner 2008 (40) | 49 | 80 | 56.8 | Epithelial 61%; mixed 31%; sarcomatous 8% | EPP | 33.98 | 53 | – |

| Arrossi 2008 (41) | 56 | 89 | 61 | Epithelioid 66%; sarcomatoid 16%; biphasic 11%; undetermined 7% | EPP | 13.88 | – | – |

| Schipper 2008 (24) | 285/73# | 83 | 62.3 | Epithelial 47%; sarcomatous 14%; biphasic 14%; desmoplastic 10%; undetermined 8% | EPP | – | 61 | 25 |

| Yan 2009 (42) | 456/70# | 86 | 66 | Epithelial 41%; sarcomatoid; biphasic 40%; undetermined 19% | EPP | 36 | 62 | 41 |

| Hasani 2009 (43) | 18 | 83 | 55.8 | NA | EPP | 19.8 | 76 | 22 |

| Krug 2009 (44) | 77/40# | 73 | 63 | Epithelial 80%; mixed 3%; sarcomatoid 1%; undetermined 16% | EPP + RT | 90 | 61.2 | |

| Zellos 2009 (45) | 29 | 76 | N/A | Epithelial 83%; non–epithelial 17% | EPP | – | 83 | 48 |

| Trousse 2009 (46) | 83 | 78 | 58 | Epithelial 82%; biphasic 16%; sarcomatoid 2% | EPP | – | 62.4 | 32.2 |

| Okubo 2009 (47) | 16 | 94 | 63.6 | Epithelioid 63%; sarcomatoid 25%; biphasic 12% | EPP | – | – | 53.3 |

| Luckraz 2010 (24) | 12 | 100 | 57.8 | Epithelioid 67% | EPP | – | – | 8 |

| Luckraz 2010 (24) | 14 | 100 | 56.3 | Epithelioid 57% | EPP + CT | – | – | 14 |

| Luckraz 2010 (24) | 15 | 80 | 51.5 | Epithelioid 33% | EPP + CT + RT | – | – | 24 |

| Treasure 2011 (48) | 24 | 96 | 61.5 | Epithelioid 83%; mixed 13%; unknown 4% | EPP | 13.2 | 52.2 | – |

| Tonoli 2011 (49) | 56 | 82 | 57.8 | Epithelioid 97%; biphasic 3% | EPP | – | 79 | 64 |

| Nakas 2012 (26) | 165/98# | 84 | 55.4 | Epithelial 78%; biphasic 22% | EPP | – | 58 | 30 |

| Lang-Lazdunski 2012 (50) | 22 | 91 | 61 | Epithelioid 63.6%; non–epithelioid 36.4% | EPP | – | 54.5 | 18.2 |

| Nakas 2014 (28) | 112 | 86 | 59 | Epithelioid 77%; biphasic 23% | EPP | – | 73 | 40 |

| Sugarbaker 2014 (51) | 529 | 75 | 53.5 | Epithelial 92%; biphasic 3%; undetermined 5% | EPP | – | 67 | 39 |

| Bovolato 2014 (29) | 301 | 75 | 57.1 | Epithelial 86.6%; biphasic 13.4%; unknown 1% | EPP | – | – | 37 |

| Mean age/survival | – | – | 57.58 | – | – | 24 | 67 | 36 |

| Surgery unspecified | ||||||||

| Moskal (52) 1998 | 37 | 78 | 54.0 | Epithelial 62.5%; biphasic 25%; sarcomatous 12.5% | – | – | – | 23 |

| Rea 2007 (37) | 21 | 67 | 55.8 | Epithelial 95%; mixed 5% | – | – | – | 52 |

| Borasio 2008 (53) | 394/26# | 69 | 62.3 | Epithelial 67.2%; biphasic 23%; sarcomatous 9.8% | – | – | – | 18.8 |

| Iyoda 2008 (54) | 32 | 97 | 55.0 | Epithelial 53.1%; sarcomatous and biphasic 43.8%; unknown 3.1% | – | – | 67.9 | 35 |

| Nakas 2014 (28) | 252 | 86 | 59 | Epithelioid 77%; biphasic 23% | – | – | – | 30 |

| Yang 2016 (55) | 284 | 76 | 67^ | Epithelioid 81%; biphasic 19% | – | – | 63 | – |

| Batirel 2016 (56) | 130 | 58 | 55.7 | Epithelioid 74.6%; mixed 20%; sarcomatoid or desmoplastic 5.4% | – | – | – | 32 |

| Mean age/survival | – | – | 58.4 | – | – | – | 64 | 30 |

#, n who received treatment; @, disease specific survival; ^, median. N/A, not available; CT, chemotherapy; RT, radiotherapy; TTP, thoracoscopic talc poudrage; VAT, video-assisted thoracoscopic; P/D, pleurectomy decortication; VAT-PP, video-assisted thoracoscopic partial pleurectomy.

Studies characteristics

There were 5 articles reporting on survival after talc pleurodesis; the size of the studies ranged from 26 to 172 patients (Table 1). There were 19 articles, including 26 different patient treatment groups, reporting on P/D, with sample sizes varying from 10 to 202 patients (Table 1). Twenty-eight articles, including 31 different patient treatment groups, reported on EPP with sample sizes varying from 12 to 529 patients (Table 1). Seven articles reported on unspecified surgery with sample sizes varying from 21 to 284 (Table 1). Most of the patients were male (≥58%) across all study groups. The overall mean age for the talc pleurodesis, P/D, EPP, unspecified surgery group were 67.5, 60.9, 57.6 and 58.4 years, respectively. Epithelial/epithelioid mesothelioma was the most frequent histology which was also consistent for all study groups.

Mean survival

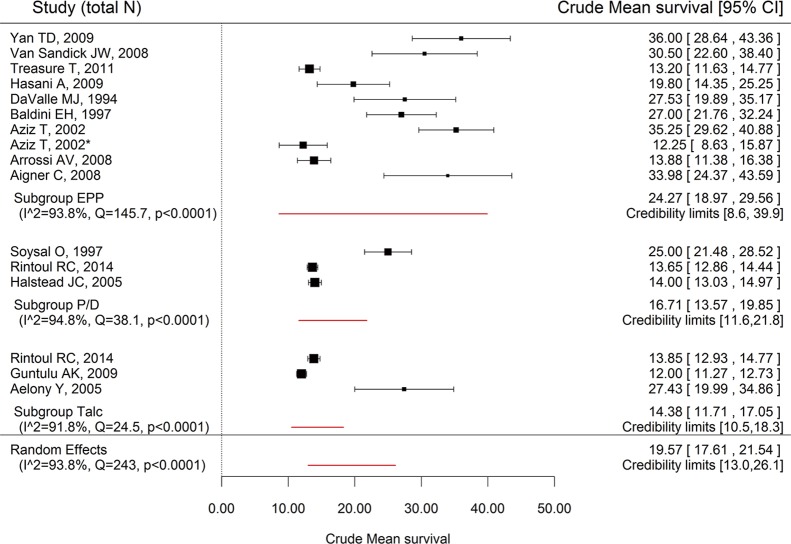

There were 3 datasets (6,11,12) that reported information to calculate the mean survival for the talc pleurodesis group; 3 (6,15,20) and 10 (31-33,39-43,48) datasets reported mean survival for the P/D and EPP groups, respectively. The mean survival in the talc pleurodesis group was 14 months [credibility limits (CL): 8.6–39.9] compared to 17 (CL: 11.6–21.8) and 24 months (CL: 10.5–18.3) for the P/D group and EPP group, respectively. There was high heterogeneity across studies for the EPP group (I2=93.8%; Q =145.7, P<0.0001) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mean overall survival. *, EPP without chemotherapy. CI, confidence interval; I2, statistic for heterogeneity; Q, statistic for heterogeneity; EPP, extrapleural pneumonectomy.

Overall survival

Two datasets reported the 1-year overall survival for the talc pleurodesis group (6,10): the values were 17% and 57%. Thirty seven datasets reported 1-year overall survival for P/D, EPP or unspecified surgery (Table 1). The pooled 1-year overall survivals in the P/D and EPP group were 55% (CL: 21–87%) and 67% (CL: 3–89%), respectively, with significant heterogeneity [I2=85.0%; Q=93.6 (P<0.001) and I2=94.8%; Q=759.2 (P<0.0001), respectively]. The pooled 1-year survival for surgery independently from the type of surgery was 62% (CL: 38–84%), with significant heterogeneity (I2=78.6%; Q=167.6, P<0.0001). Two datasets reported the 2-year overall survival for the talc pleurodesis group (10,13); this ranged from 10% to 13%. Forty eight datasets reported 2-year overall survival for P/D, EPP or unspecified surgery (Table 1). The pooled 2-year overall survival in the P/D and EPP group were 32% (CL: 8–63%) and 36% (CL: 8–54%), respectively, with significant heterogeneity [I2=81.2%; Q=95.5 (P<0.001) and I2=83.1%; Q=260.4 (P<0.0001), respectively]. The pooled 2-year survival for surgery independently from the type of surgery was 34% (CL: 16–54%), with significant heterogeneity (I2 =73.6%; Q=178.2 P<0.0001).

Discussion

This study assesses survival in patients with MPM comparing surgery to talc pleurodesis. When talc and surgery are compared, the mean survival for patients treated with surgery was higher compared to talc pleurodesis. This is consistent with identifying pleurodesis as a palliative therapy in MPM patients (2). Dyspnea, caused by the accumulation of fluids in the pleural space, is an important symptom among MPM patients which negatively impacts quality of life (5). Talc pleurodesis is shown to be effective, safe and successful in the prevention of fluid accumulation achieving a long-term control with a marked improvement of dyspnea (4).

The studies reporting on 1-year survival are scarce for talc and prevent any firm conclusion; such studies however suggest that surgery is still the nest option, and that EPP patients fare better than P/D patients. There are notable differences in patients treated with one surgical procedure versus the other. Mean age of patients treated with P/D is higher than patients treated with EPP, 60.9 and 57.6 years, respectively. Other patient characteristics such as overall performance status and cardiopulmonary function probably also differ between the patients treated with the two procedures (2). Older patients with decreased mobility and cardiopulmonary function are more likely to be treated with P/D instead of EPP (2); this selection bias has probably affected the overall survival. The high heterogeneity observed when pooling studies likely reflects differences in study design, inclusion criteria, and other selection criteria operated by each investigator when deciding to perform EPP or P/D.

The only randomized controlled trial directly compared the efficacy of VAT-PP and talc pleurodesis in MPM patients (6), reported that overall survival was similar for the two treatment groups; VAT-PP was associated with a longer hospital stay and higher costs than talc pleurodesis. On the other hand, VAT-PP had a significantly better quality of life score at 6 and 12 months than the talc pleurodesis group. The equipoise reported in the clinical trial is probably due to the fact that patients had to be fit enough to undergo VAT-PP to be eligible to be included into this trial. Patients included in this trial were therefore probably in better physical condition than patients receiving talc pleurodesis in the observational studies summarized in this review, which included unselected groups of patients, many of which were probably treated with palliative intent.

This review has some limitations. Only one study directly compared surgery with talc pleurodesis; in general, the number of studies conducted on talc pleurodesis is very small, and makes it difficult to draw any conclusion. Furthermore, the choice for surgery or talc pleurodesis may have been based on clinical reasons, such as the stage of the disease, histology, age of the patient or presence of comorbidities, all factors which are not reported in the publication but may have introduced selection bias and influenced survival. Another limitation is the large amount of heterogeneity between the data sets. This indicates that other factors, such as variations in the procedural approach and execution, the varying ability of surgeons, the degree of specialization of the center performing the procedure, or the inconsistency of data definitions across institutions, may have impacted survival in each study. Finally, we were unable to account for effects of other treatments in addition to surgery or talc pleurodesis because of the retrospective nature of the review.

Conclusions

This review shows that there is limited data on the effect of talc pleurodesis compared to surgery in MPM patients with regards to survival rates. A comparison study is necessary to accurately assess the best way to treat MPM patients. Because MPM is an aggressive disease with a poor prognosis, assessment of the quality of life after treatment should be included as an outcome measure.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Yang H, Testa JR, Carbone M. Mesothelioma epidemiology, carcinogenesis, and pathogenesis. Curr Treat Options Oncol 2008;9:147-57. 10.1007/s11864-008-0067-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paul S, Neragi-Miandoab S, Jaklitsch MT. Preoperative assessment and therapeutic options for patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma. Thorac Surg Clin 2004;14:505-16. 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2004.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taioli E, Wolf AS, Flores RM. Meta-analysis of survival after pleurectomy decortication versus extrapleural pneumonectomy in mesothelioma. Ann Thorac Surg 2015;99:472-80. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.09.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barbetakis N, Asteriou C, Papadopoulou F, et al. Early and late morbidity and mortality and life expectancy following thoracoscopic talc insufflation for control of malignant pleural effusions: a review of 400 cases. J Cardiothorac Surg 2010;5:27. 10.1186/1749-8090-5-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas R, Francis R, Davies HE, et al. Interventional therapies for malignant pleural effusions: the present and the future. Respirology 2014;19:809-22. 10.1111/resp.12328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rintoul RC, Ritchie AJ, Edwards JG, et al. Efficacy and cost of video-assisted thoracoscopic partial pleurectomy versus talc pleurodesis in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma (MesoVATS): an open-label, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet 2014;384:1118-27. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60418-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol 2005;5:13. 10.1186/1471-2288-5-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002;21:1539-58. 10.1002/sim.1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ioannidis JP, Patsopoulos NA, Evangelou E. Uncertainty in heterogeneity estimates in meta-analyses. BMJ 2007;335:914. 10.1136/bmj.39343.408449.80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phillips PG, Asimakopoulos G, Maiwand MO. Malignant pleural mesothelioma: outcome of limited surgical management. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2003;2:30-4. 10.1016/S1569-9293(02)00093-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aelony Y, Yao JF. Prolonged survival after talc poudrage for malignant pleural mesothelioma: case series. Respirology 2005;10:649-55. 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2005.00763.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ak G, Metintaş M, Yildirim H, et al. Pleurodesis in follow-up and treatment of malignant pleural mesothelioma patients. Tuberk Toraks 2009;57:22-31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rena O, Boldorini R, Papalia E, et al. Persistent lung expansion after pleural talc poudrage in non-surgically resected malignant pleural mesothelioma. Ann Thorac Surg 2015;99:1177-83. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.11.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sauter ER, Langer C, Coia LR, et al. Optimal management of malignant mesothelioma after subtotal pleurectomy: revisiting the role of intrapleural chemotherapy and postoperative radiation. J Surg Oncol 1995;60:100-5. 10.1002/jso.2930600207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soysal O, Karaoglanoglu N, Demircan S, et al. Pleurectomy/decortication for palliation in malignant pleural mesothelioma: results of surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1997;11:210-3. 10.1016/S1010-7940(96)01008-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin-Ucar A, Edwards J, Rengajaran A, et al. Palliative surgical debulking in malignant mesothelioma Predictors of survival and symptom control. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2001;20:1117-21. 10.1016/S1010-7940(01)00995-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ceresoli GL, Locati LD, Ferreri AJ, et al. Therapeutic outcome according to histologic subtype in 121 patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma. Lung Cancer 2001;34:279-87. 10.1016/S0169-5002(01)00257-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takagi K, Tsuchiya R, Watanabe Y. Surgical approach to pleural diffuse mesothelioma in Japan. Lung Cancer 2001;31:57-65. 10.1016/S0169-5002(00)00152-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee TT, Everett DL, Shu HK, et al. Radical pleurectomy/decortication and intraoperative radiotherapy followed by conformal radiation with or without chemotherapy for malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2002;124:1183-9. 10.1067/mtc.2002.125817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halstead JC, Lim E, Venkateswaran R, et al. Improved survival with VATS pleurectomy-decortication in advanced malignant mesothelioma. Eur J Surg Oncol (EJSO) 2005;31:314-20. 10.1016/j.ejso.2004.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin-Ucar AE, Nakas A, Edwards JG, et al. Case-control study between extrapleural pneumonectomy and radical pleurectomy/decortication for pathological N2 malignant pleural mesothelioma. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2007;31:765-70. 10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.01.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakas A, Trousse DS, Martin-Ucar AE, et al. Open lung-sparing surgery for malignant pleural mesothelioma: the benefits of a radical approach within multimodality therapy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2008;34:886-91. 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schipper PH, Nichols FC, Thomse KM, et al. Malignant pleural mesothelioma: surgical management in 285 patients. Ann Thorac Surg 2008;85:257-64. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.06.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luckraz H, Rahman M, Patel N, et al. Three decades of experience in the surgical multi-modality management of pleural mesothelioma. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2010;37:552-6. 10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.07.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bölükbas S, Manegold C, Eberlein M, et al. Survival after trimodality therapy for malignant pleural mesothelioma: radical pleurectomy, chemotherapy with cisplatin/pemetrexed and radiotherapy. Lung Cancer 2011;71:75-81. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakas A, Meyenfeldt E, Lau K, et al. Long-term survival after lung-sparing total pleurectomy for locally advanced (International Mesothelioma Interest Group Stage T3–T4) non-sarcomatoid malignant pleural mesothelioma. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2012;41:1031-6. 10.1093/ejcts/ezr192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friedberg JS, Culligan MJ, Mick R, et al. Radical pleurectomy and intraoperative photodynamic therapy for malignant pleural mesothelioma. Ann Thorac Surg 2012;93:1658-65. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakas A, Waller D. Predictors of long-term survival following radical surgery for malignant pleural mesothelioma. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2014;46:380-5. 10.1093/ejcts/ezt664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bovolato P, Casadio C, Billè A, et al. Does surgery improve survival of patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma: a multicenter retrospective analysis of 1365 consecutive patients. J Thorac Oncol 2014;9:390-6. 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lang-Lazdunski L, Bille A, Papa S, et al. Pleurectomy/decortication, hyperthermic pleural lavage with povidone-iodine, prophylactic radiotherapy, and systemic chemotherapy in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma: a 10-year experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2015;149:558-65. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.10.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DaValle MJ, Faber LP, Kittle CF, et al. Extrapleural pneumonectomy for diffuse, malignant mesothelioma. Ann Thorac Surg 1986;42:612-8. 10.1016/S0003-4975(10)64593-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baldini EHM, Recht A, Strauss GM, et al. Patterns of failure after trimodality therapy for malignant pleural mesothelioma. Ann Thorac Surg 1997;63:334-8. 10.1016/S0003-4975(96)01228-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aziz T, Jilaihawi A, Prakash D. The management of malignant pleural mesothelioma; single centre experience in 10 years. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2002;22:298-305. 10.1016/S1010-7940(02)00273-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ahamad A, Stevens CW, Smythe WR, et al. Promising early local control of malignant pleural mesothelioma following postoperative intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) to the chest. Cancer J 2003;9:476-84. 10.1097/00130404-200311000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Edwards JG, Stewart D, Martin-Ucar A, et al. The pattern of lymph node involvement influences outcome after extrapleural pneumonectomy for malignant mesothelioma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2006;131:981-7. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.11.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pagan V, Ceron L, Paccagnella A, et al. 5-year prospective results of trimodality treatment for malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2006;47:595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rea F, Marulli G, Bortolotti L, et al. Induction chemotherapy, extrapleural pneumonectomy (EPP) and adjuvant hemi-thoracic radiation in malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM): Feasibility and results. Lung Cancer 2007;57:89-95. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rice DC, Stevens CW, Correa AM, et al. Outcomes after extrapleural pneumonectomy and intensity-modulated radiation therapy for malignant pleural mesothelioma. Ann Thorac Surg 2007;84:1685-92. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.04.076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Sandick JW, Kappers I, Baas P, et al. Surgical treatment in the management of malignant pleural mesothelioma: a single institution’s experience. Ann Surg Oncol 2008;15:1757. 10.1245/s10434-008-9899-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aigner C, Hoda MA, Lang G, et al. Outcome after extrapleural pneumonectomy for malignant pleural mesothelioma. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2008;34:204-7. 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arrossi AV, Lin E, Rice D, et al. Histologic assessment and prognostic factors of malignant pleural mesothelioma treated with extrapleural pneumonectomy. Am J Clin Pathol 2008;130:754-64. 10.1309/AJCPHV33LJTVDGJJ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yan TD, Boyer M, Tin MM, et al. Extrapleural pneumonectomy for malignant pleural mesothelioma: outcomes of treatment and prognostic factors. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2009;138:619-24. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.12.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hasani A, Alvarez JM, Wyatt JM, et al. Outcome for patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma referred for Trimodality therapy in Western Australia. J Thorac Oncol 2009;4:1010-6. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181ae25bf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krug LM, Pass HI, Rusch VW, et al. Multicenter phase II trial of neoadjuvant pemetrexed plus cisplatin followed by extrapleural pneumonectomy and radiation for malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:3007-13. 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.3943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zellos L, Richards WG, Capalbo L, et al. A phase I study of extrapleural pneumonectomy and intracavitary intraoperative hyperthermic cisplatin with amifostine cytoprotection for malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2009;137:453-8. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.07.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trousse DS, Avaro JP, D’journo XB, et al. Is malignant pleural mesothelioma a surgical disease? A review of 83 consecutive extra-pleural pneumonectomies. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2009;36:759-63. 10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.04.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Okubo K, Sonobe M, Fujinaga T, et al. Survival and relapse pattern after trimodality therapy for malignant pleural mesothelioma. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2009;57:585. 10.1007/s11748-009-0440-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Treasure T, Lang-Lazdunski L, Waller D, et al. Extra-pleural pneumonectomy versus no extra-pleural pneumonectomy for patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma: clinical outcomes of the Mesothelioma and Radical Surgery (MARS) randomised feasibility study. Lancet Oncol 2011;12:763-72. 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70149-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tonoli S, Vitali P, Scotti V, et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy after extrapleural pneumonectomy for mesothelioma. Prospective analysis of a multi-institutional series. Radiother Oncol 2011;101:311-5. 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.09.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lang-Lazdunski L, Bille A, Lal R, et al. Pleurectomy/decortication is superior to extrapleural pneumonectomy in the multimodality management of patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Thorac Oncol 2012;7:737-43. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31824ab6c5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sugarbaker DJ, Richards WG, Bueno R. Extrapleural pneumonectomy in the treatment of epithelioid malignant pleural mesothelioma: novel prognostic implications of combined N1 and N2 nodal involvement based on experience in 529 patients. Ann Surg 2014;260:577. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moskal TL, Dougherty TJ, Urschel JD, et al. Operation and photodynamic therapy for pleural mesothelioma: 6-year follow-up. Ann Thorac Surg 1998;66:1128-33. 10.1016/S0003-4975(98)00799-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Borasio P, Berruti A, Billé A, et al. Malignant pleural mesothelioma: clinicopathologic and survival characteristics in a consecutive series of 394 patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2008;33:307-13. 10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.09.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Iyoda A, Yusa T, Kadoyama C, et al. Diffuse malignant pleural mesothelioma: A multi-institutional clinicopathological study. Surg Today 2008;38:993-8. 10.1007/s00595-008-3776-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang CJ, Yan BW, Meyerhoff RR, et al. Impact of Age on Long-Term Outcomes of Surgery for Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Clin Lung Cancer 2016;17:419-26. 10.1016/j.cllc.2016.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Batirel HF, Metintas M, Caglar HB, et al. Adoption of pleurectomy and decortication for malignant mesothelioma leads to similar survival as extrapleural pneumonectomy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2016;151:478-84. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.09.121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]