Abstract

Background: Patients with advanced pancreatic cancer suffer from high morbidity and mortality. Specialty palliative care may improve quality of life.

Objective: Assess the feasibility, acceptability, and perceived effectiveness of early specialty physician-led palliative care for patients with advanced pancreatic cancer and their caregivers.

Design: A mixed-methods pilot randomized controlled trial in which patient-caregiver pairs were randomized (2:1) to receive specialty palliative care, in addition to standard oncology care versus standard oncology care alone.

Setting/Subjects: At a National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive cancer center in Western Pennsylvania, 30 patients with advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma and their caregivers (N = 30), oncologists (N = 4), and palliative care physicians (N = 3) participated.

Measurements: Feasibility (enrollment, three-month outcome-assessment, and intervention completion rates), acceptability, and perceived effectiveness (process interviews with patients, caregivers, and physicians).

Results: Consent:approach rate was 49%, randomized:consent rate 55%, and three-month outcome assessment rate 75%. Two patients and three caregivers withdrew early. The three-month mortality rate was 13%. Patients attended a mean of 1.3 (standard deviation 1.1) palliative care visits during the three-month period. Positive experiences with palliative care included receiving emotional support and symptom management. Negative experiences included inconvenience, long travel times, spending too much time at the cancer center, and no perceived palliative care needs. Physicians suggested embedding palliative care within oncology clinics, tailoring services to patient needs, and facilitating face-to-face communication between oncologists and palliative physicians.

Conclusions: A randomized trial of early palliative care for advanced pancreatic cancer did not achieve feasibility goals. Integrating palliative care within oncology clinics may increase acceptability and perceived effectiveness.

Keywords: : palliative care, pancreatic cancer, pilot trial

Introduction

Specialty palliative care decreases morbidity for patients with advanced cancer.1 A randomized trial conducted among patients with metastatic nonsmall cell lung cancer demonstrated improvements in quality of life and mood, less aggressive care near end of life, and longer survival with addition of early specialty palliative care to standard oncology care.2 Another study conducted among patients with advanced-stage solid tumor or hematologic malignancy demonstrated improved one-year survival rates and improved caregiver outcomes with early versus delayed initiation of specialty palliative care, although there was no difference in patient-reported outcomes or resource use.3,4 A trial of systematic versus on-demand early palliative care conducted among patients with advanced pancreatic cancer in Italy demonstrated improved physical, functional, and disease-specific quality of life in the group receiving systematic early palliative care.5

In response to accumulating research, professional guidelines put forth by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) now recommend early comanagement by palliative care specialists for all patients with advanced cancer.6

However, barriers to early specialty palliative care use persist. A prior in-depth interview study with oncologists practicing at three academic cancer centers across the United States with well-established palliative care services identified misperceptions about palliative care as an alternative to cancer-directed therapy, oncologists' preferences in maintaining control of palliative aspects of care, concerns that specialty referrals may create confusion or send “mixed messages about life-prolonging therapy,” and a lack of knowledge about palliative services.7 Oncologists suggested clarifying the role of palliative care clinicians, improving communication between oncologists and palliative care clinicians, and designing disease-specific palliative care interventions to meet the unique needs of different patient populations.

In response to these findings, we convened a series of working groups with oncologists and palliative care physicians to develop a collaborative model of specialist palliative care comanagement. We chose to focus on advanced pancreatic cancer because it is a disease with high morbidity and mortality for which oncologists felt that patients and families would benefit from earlier palliative care visits. With input from working group members, we created an intervention manual with guidelines for palliative care visits, as well as communication between oncologists and palliative care physicians. We then designed a pilot trial to test the feasibility, acceptability, and perceived effectiveness of our approach among patients with recently diagnosed pancreatic cancer, their family caregivers, oncologists, and palliative care physicians.

In this article, we describe the findings of our pilot study, while highlighting significant challenges and lessons learned. We hope that these insights will aid clinicians, other healthcare professionals, and researchers seeking to integrate and evaluate early specialty palliative care interventions in advanced cancer populations.

Methods

Study rationale and design

We conducted a pilot randomized controlled trial designed to assess feasibility, acceptability, and perceived effectiveness of a physician-led specialty palliative care intervention for patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. We enrolled 30 patients with recently diagnosed advanced pancreatic cancer, as well as their caregivers, primary oncologists, and palliative care physicians.

Patient-caregiver pairs were randomized (2:1) to receive early specialty palliative care, in addition to standard oncology care or standard oncology care alone. We chose a 2:1 randomization scheme to allow us to assess the feasibility of randomizing participants in this pilot study, while maximizing exposure to the palliative care intervention.

Patient and caregiver outcomes were assessed at baseline and three months. Monthly check-in calls were employed to remind participants of upcoming palliative care visits (intervention group only) and assess healthcare utilization. When appropriate, caregivers also completed bereavement interviews one to three months after the patient's death. We interviewed oncologists and palliative care physicians at three and nine months after initiating trial participation to elicit experiences with early specialty palliative care and recommendations for improvement.

The study protocol was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board and registered on Clinical Trials.gov (Identifier NCT01885884).

Setting

The trial was conducted at the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute (UPCI), an academic, National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive cancer center in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. This cancer center serves as a tertiary referral center for Western Pennsylvania and includes a weekly, multidisciplinary pancreatic cancer specialty clinic. In 2013, this specialty clinic saw 374 patients with newly diagnosed pancreatic cancer.

Intervention

The intervention consisted of in-person palliative care visits with a specialty-trained palliative care physician. Visits were held in the same building as oncology appointments, and every effort was made to schedule oncology and palliative care visits on the same day. Follow-up intervention visits were scheduled monthly for the first three months, and as needed thereafter. More frequent palliative care visits were allowed in the event that additional needs were identified. Participants did not incur a copay or bill for palliative care visits; they received $40 upon completion of the first visit and $25 to cover travel costs for all subsequent palliative care visits that could not be scheduled on the same day as a regularly scheduled oncology appointment.

Immediately before each visit, patients completed a survey that asked “what would you most like to discuss with your supportive care doctor today?” and assessed symptom burden (Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale [ESAS]8) and distress (Distress thermometer).9 Caregivers completed a 4-item measure of caregiver burden (Zarit Screening Interview10) and the Distress Thermometer.9

Visit content, as guided by patient- and caregiver-reported outcomes and National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care Clinical Practice Guidelines,11 included the following: (1) relationships and rapport building; (2) illness understanding, preferences, and concerns; (3) patient and caregiver needs, including physical symptoms, psychological/emotional distress, and social/financial/caregiver burden; and (4) resources, review, and next steps. An intervention manual describing key visit domains, suggested language, and study processes was distributed to all participating oncologists and palliative care physicians (Supplementary Data; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/jpm).

In addition, an e-mail was sent to the patient's oncologist and palliative care physician before and after each palliative care visit. This e-mail was intended to (1) remind clinicians about study participation and (2) encourage oncologist-palliative care communication about key changes in patient symptoms, functioning, distress, or goals of care. All participating oncologists and palliative care physicians were familiar to each other as professional colleagues at the same institution.

Usual care

Usual care included standard oncology care. Usual care participants had access to any palliative care service that was deemed appropriate.

Participants

We included adults (≥18 years old) with pathologically confirmed, locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma, diagnosed within the past eight weeks. Eligible participants had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 (asymptomatic), 1 (symptomatic but fully ambulatory), or 2 (symptomatic and in bed <50% of the day); were planning to receive ongoing care from an oncologist at the cancer center; and had an identifiable caregiver (family member or friend) who could accompany them to visits. We excluded patients who were unable to read and respond to questions in English.

Given slower-than-expected enrollment, we expanded our eligibility criteria to include patients with borderline-resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma 20 weeks into the recruitment period.

Caregivers were enrolled if they were the adult (≥18 years old) family member or friend of an eligible patient, identified as the person most likely to accompany the patient to visits or help with their care should they need it, and able to read and respond to questions in English.

All medical oncology and palliative care physicians caring for participating patients at UPCI were eligible for enrollment.

All participants provided written informed consent.

Recruitment, enrollment, and randomization

Patients were recruited from a weekly multidisciplinary clinic for patients with recently diagnosed pancreatic cancer. The clinic coordinator identified potentially eligible patients during the week before each clinic as part of her routine review of medical records. On the clinic day, patients were approached first by a clinical staff member to ask if they would be willing to hear more about the study. This approach avoided the potential for any cold calling by researchers. In the event a patient was willing to hear more, a research staff member described the study further and conducted the consent process. Patients were asked to identify a caregiver. Patient-caregiver pairs who subsequently met eligibility criteria were enrolled and randomized using a computer-generated randomization table to receive either the specialty palliative care intervention or usual care in a 2:1 ratio.

Measurements

Feasibility

Feasibility was assessed through (1) enrollment rates, (2) intervention completion rates, and (3) three-month outcome assessment rates. Our targets for achieving adequate feasibility were a consent:approach rate of ≥60%, a randomized: consent rate of ≥60%, an intervention completion rate of ≥70%, and three-month outcome assessment rates of ≥80%.12

Acceptability and perceived effectiveness

Acceptability was assessed by tracking participant withdrawal rates. Process interviews conducted with patients and caregivers (three months) assessed acceptability and perceived effectiveness of the early specialty palliative care intervention and included open-ended questions to assess experiences with early specialty palliative care. Process interviews conducted with oncologists and palliative care physicians (three and nine months) included open-ended questions to assess experiences with the early specialty palliative care intervention, as well as recommendations for improvement.

Patient and family caregiver outcomes

Patient and family caregiver outcomes assessed through baseline and three-month surveys included demographics; patient quality of life (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—Hepatobiliary Questionnaire [FACT-Hep],13 Quality of Life at the End of Life [QUAL-E],14 and Peace, Equanimity, and Acceptance in the Cancer Experience [PEACE]15 Scales); patient and caregiver mood symptoms (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [HADS],16 Distress Thermometer,9 and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 [PHQ-917—patient only]); and caregiver burden (Zarit Burden Interview—Short).10 Caregiver bereavement surveys additionally assessed preparedness for death18 and complicated grief (Inventory of Complicated Grief).19

Analyses

Quantitative data were summarized using descriptive statistics. We did not conduct comparisons between groups because this was a pilot trial that was not designed to assess efficacy. Open-ended process interviews with patients, caregivers, oncologists, and palliative care physicians were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and reviewed by two study investigators to identify and categorize positive and negative experiences with palliative care, as well as recommendations for improvement.

Results

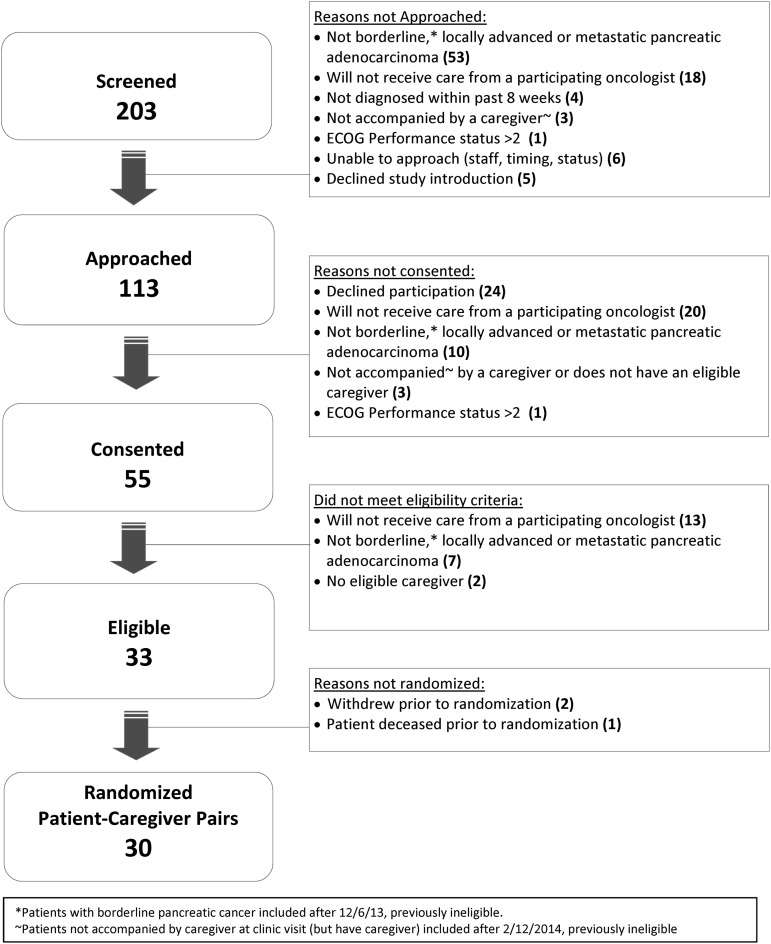

A total of 203 patients were screened, of whom 113 were approached for study participation. Our consent:approach rate was 49% and our randomized: consent rate was 55% (both below target). Of the 113 approached patients, 33 (29%) were not eligible because they were not planning to continue to receive care from a participating oncologist at the cancer center; most often these patients were planning to receive care with a local community oncologist. We reached our goal of 30 patient-caregiver pairs after 50 weeks of recruitment. The CONSORT diagram is shown in Figure 1.

FIG. 1.

CONSORT diagram.

The mean patient age was 63 (standard deviation [SD] 11) years; 50% were male. Patient and caregiver participants were predominantly Caucasian and married. Caregivers were most frequently the patient's spouse or partner. Additional demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline Participant Characteristicsa

| Patients (N = 30) | Caregivers (N = 30) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 63 (11) | 62 (12) |

| Male | 15 (50) | 14 (47) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 29 (100) | 29 (97) |

| Decline to answer | 1 (3) | 1 (3) |

| Religion | ||

| Roman Catholic | 12 (40) | 13 (43) |

| Protestant and other Christian | 12 (40) | 14 (47) |

| Jewish | 1 (3) | 1 (3) |

| Agnostic/atheist/no religion | 2 (7) | 1 (3) |

| Decline to answer | 3 (10) | 1 (3) |

| Importance of religion | ||

| Very important | 14 (47) | 14 (47) |

| Fairly important | 9 (30) | 10 (33) |

| Not too important | 3 (10) | 5 (17) |

| Not at all important | 4 (13) | 1 (3) |

| Highest education completed | ||

| Less than high school | 1 (3) | 1 (3) |

| High school or GED | 5 (17) | 11 (37) |

| Some college | 6 (20) | 8 (27) |

| Completed college | 4 (13) | 4 (13) |

| One or more years post-graduate | 14 (47) | 6 (20) |

| Marital status | ||

| Never married | 2 (7) | 1 (3) |

| Married | 24 (80) | 27 (90) |

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 3 (10) | 1 (3) |

| Decline to answer | 1 (3) | 1 (3) |

| Employment status | ||

| Working full time | 8 (27) | 11 (37) |

| Working part time | 0 (0) | 3 (10) |

| Unemployed | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Retired | 17 (57) | 14 (47) |

| Homemaker (never worked for pay) | 0 | 1 (3) |

| Other/decline to answer | 5 (17) | 1 (3) |

| Manage on current income | ||

| Cannot make ends meet | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Just manage to get by | 7 (23) | 6 (20) |

| Have enough money with a little extra | 12 (40) | 15 (50) |

| Money is not a problem | 8 (27) | 4 (13) |

| Decline to answer/no response | 3 (10) | 5 (17) |

| Disease stage | ||

| Metastatic | 12 (40) | — |

| Borderline or locally advanced | 18 (60) | — |

| ECOG performance status | ||

| 0 | 13 (43) | — |

| 1 | 15 (50) | — |

| 2 | 2 (7) | — |

| Relationship to patient | ||

| Spouse/partner | — | 24 (80) |

| Child | — | 2 (7) |

| Parent | — | 2 (7) |

| Sibling | — | 1 (3) |

| Other relative | — | 1 (3) |

| Lives with patient | — | 26 (87) |

All data N (%) except where indicated otherwise.

ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; SD, standard deviation; GED, General Education Development.

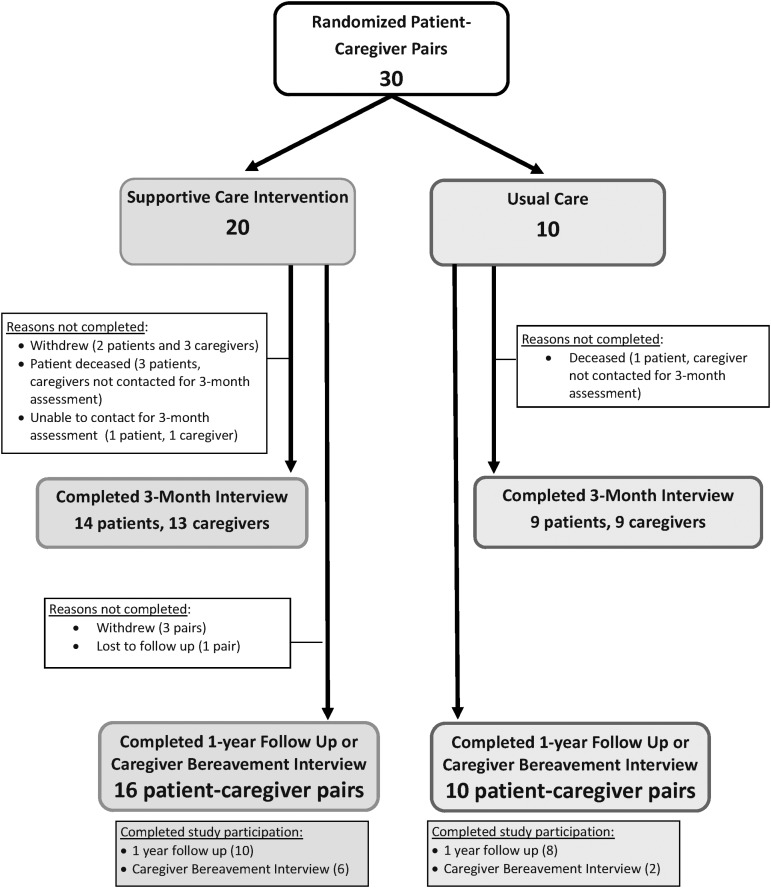

Three patients and two caregivers withdrew from the study; an additional four patients died before three months (Fig. 2). The three-month outcome assessment rate was 75% (target 80%). Baseline and three-month outcome assessments are shown in Table 2.

FIG. 2.

Participation of randomized patient-caregiver pairs.

Table 2.

Baseline and Three-Month Outcome Assessments

| Patients | Caregivers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention (N = 20) | Usual care (N = 10) | Intervention (N = 20) | Usual care (N = 10) | |

| Quality-of-life measures | ||||

| FACT-Hep | ||||

| Baseline | 122.3 (24.5) | 121.7 (23.1) | — | — |

| Three-month | 134.7 (22.0) | 122.6 (16.8) | — | — |

| QUAL-E | ||||

| Three-month | 65.1 (14.8) | 63.8 (8.1) | — | — |

| PEACE scale | ||||

| Three-month | ||||

| Peaceful acceptance subscale | 17.6 (2.4) | 18.4 (1.8) | — | — |

| Struggle with illness subscale | 11.9 (3.9) | 14.6 (3.3) | — | — |

| Mood symptoms | ||||

| HADS | ||||

| Anxiety subscale | ||||

| Baseline | 6.7 (4.4) | 6.0 (3.4) | 10.5 (4.8) | 9.3 (3.1) |

| Three-month | 4.6 (2.3) | 6.3 (2.9) | 8.4 (3.6) | 7 (2.1) |

| Depression subscale | ||||

| Baseline | 5.9 (5.3) | 6.8 (3.6) | 6.7 (3.5) | 5.5 (3.8) |

| Three-month | 5.1 (4.3) | 5.9 (3.6) | 5.2 (4.1) | 4.2 (2.6) |

| PHQ-9 | ||||

| Baseline | 6.9 (4.6) | 8.6 (6.1) | — | — |

| Three-month | 4.6 (3.7) | 7.1 (3.4) | — | — |

| Distress | ||||

| Baseline | 4.3 (3.2) | 4.2 (2.4) | 5.9 (2.7) | 5.0 (3.0) |

| Three-month | 2.9 (2.4) | 4.0 (2.3) | 5.0 (2.5) | 3.4 (1.5) |

| Caregiver burden | ||||

| Zarit Burden Interview—Short | ||||

| Baseline | — | — | 11.6 (7.1) | 11.0 (7.0) |

| Three-month | — | — | 14.6 (9.9) | 10.7 (7.1) |

All data presented as mean (SD). FACT-Hep: scores range 0–180; higher scores indicate better health-related quality of life. QUAL-E: used questions 6–26 of original measure; total scores range 17–85; questions 11, 17, 25, and 26 scored separately; higher scores indicate better quality of life. Peaceful Acceptance of Illness Subscale: scores range 5–20, with higher scores indicating greater acceptance. Struggle with Illness Subscale: scores range 7–27, with higher scores indicating greater struggle. HADS: scores range 0–21 on each subscale; 0–7 Normal, 8–10 borderline abnormal, and 11–21 abnormal. PHQ-9: scores range 0–28; 0–4 no depression, 5–9 mild, 10–14 moderate, 15–19 moderately severe, and 20+ severe depression. Distress measured using Distress Thermometer. Scores range 0–10 with higher scores indicating more distress.

Zarit Burden Interview—Short: scores range 0–48 with higher scores indicating more burden.

FACT-Hep, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy for patients with Hepatobiliary cancer; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; PEACE, Peace, Equanimity, and Acceptance in the Cancer Experience; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; QUAL-E, Quality of Life at the End of Life.

In the intervention group, the mean number of specialty palliative care visits attended by patients within the three-month intervention period was 1.3 (SD 1.1), and the mean number attended by caregivers was 1.1 (SD 1.1). Six patients (30%) and eight caregivers (40%) did not attend any specialty palliative care visits within the first three months. Overall, 67% of specialty palliative care visits took place on the same day as a patient's regularly scheduled oncology appointment.

Participating oncologists responded to 49% (22 of 45) e-mail reminders to communicate about key changes in patient symptoms, functioning, distress, or goals of care. Among all oncologist responses, 68% (15 of 22) included detailed patient information and 32% (7 of 22) included an acknowledgment or thank you without patient information. Participating palliative care physicians responded to 89% (40 of 45) e-mail reminders and all responses included detailed patient information.

Patient- and caregiver-reported acceptability and perceived effectiveness of early specialty palliative care are reported in Table 3. In three-month process interviews, patient and caregiver reasons for not attending monthly specialty palliative care visits included practical challenges with additional medical appointments and not perceiving palliative care needs. Additional patient and caregiver experiences with early specialty palliative care are listed in Table 4.

Table 3.

Acceptability and Perceived Effectiveness of Early Specialty Palliative Care

| Patients (N = 14) | Caregivers (N = 13) | |

|---|---|---|

| Receiving SPC has improved my pain or other symptoms. | ||

| Strongly agree/agree | 5 (36) | — |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 3 (21) | — |

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 3 (21) | — |

| No responsea | 3 (21) | — |

| Receiving SPC has helped me to better understand my/my loved one's illness. | ||

| Strongly agree/agree | 8 (57) | 9 (69) |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 1 (7) | 1 (8) |

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 2 (14) | 1 (8) |

| No responsea | 3 (21) | 2 (15) |

| Receiving SPC has helped me to cope with my/my loved one's illness. | ||

| Strongly agree/agree | 6 (43) | 8 (62) |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 3 (21) | 2 (15) |

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 2 (14) | 1 (8) |

| No responsea | 3 (21) | 2 (15) |

| Receiving SPC has helped me to plan for the future. | ||

| Strongly agree/agree | 6 (43) | 6 (46) |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 2 (14) | 3 (23) |

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 3 (21) | 2 (15) |

| No responsea | 3 (21) | 2 (15) |

| I would recommend SPC to other patients with pancreatic cancer and their family members. | ||

| Strongly agree/agree | 10 (71) | 11 (85) |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 2 (14) | 0 (0) |

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| No responsea | 2 (14) | 2 (15) |

| I found the SPC care visits acceptable. | ||

| Yes | 10 (71) | 9 (69) |

| No | 1 (7) | 0 (0) |

| No responsea | 3 (21) | 4 (31) |

All values presented as N (%). Percentages do not always sum to 100% due to rounding. Early specialty palliative care was referred to as “supportive care” to all patient and caregiver participants.

Participants randomized to the intervention who did not take part in any SPC visits before three months were unable to answer questions about participating in them.

SPC, specialty palliative care.

Table 4.

Patient and Caregiver Experiences with Early Specialty Palliative Care

| Positive experiences | Extra layer of support, someone to listen. (N = 10) |

| Providing information about cancer and treatments, answering questions. (N = 8) | |

| Treating pain and other symptoms. (N = 5) | |

| Talking about the future, what to expect. (N = 4) | |

| More awareness of emotions related to illness. (N = 2) | |

| Ability to see both oncologist and palliative care on the same day. (N = 2) | |

| Knowing about palliative care service in case of future need. (N = 2) | |

| Help patients and caregiver talk with each other. (N = 1) | |

| Alleviating caregiver burden. (N = 1) | |

| Looking at the big picture. (N = 1) | |

| Helping to get information from other doctors. (N = 1) | |

| Coordinating care. (N = 1) | |

| Negative experiences | Too many medical appointments, spending too long at the cancer center, long travel times, having to come to the cancer center on ‘good days’ instead of spending time with family. (N = 7) |

| Hard to schedule at a convenient time. (N = 6) | |

| Having to think about things you do not want to think about (like living wills, severity of illness). (N = 4) | |

| Visits not helpful/no palliative care needs. (N = 2) | |

| Confronting emotions related to illness (both positive and negative). (N = 2) | |

| Palliative care doctors not always available to answer questions. (N = 1) |

Interviews conducted with N = 14 patients and N = 13 caregivers in the Intervention Group. Some participants expressed more than one experience.

In three- and nine-month process interviews, participating oncologists and palliative care physicians recommended tailoring the frequency and content of palliative care visits to patient/caregiver needs. As one oncologist participant said, “basically all those [palliative care] programs you need to tailor in the patient. Some people need more, some people need less.” A participating palliative care physician noted, “I think for patients who have less active needs, the role [of palliative care] is less clear.” Oncologists and palliative care physicians held mixed opinions on e-mails sent to encourage communication between specialists. Some participants found such e-mails to be helpful, while others noted that in-person communication was preferred. One oncologist said, “you know, … maybe I'm being old-fashioned, but maybe a verbal communication periodically. … sometimes it's hard when you're dealing with soft issues like anxiety and pain and things, to communicate those with an e-mail.” Other oncologists recommended embedding palliative care clinicians within disease-specific oncology clinics and reviewing patients' palliative care needs in multidisciplinary team meetings. Palliative care physicians recommended incorporating nurse-led palliative care visits to increase availability of palliative care services.

Discussion

This pilot randomized trial of early specialty palliative care for patients with advanced pancreatic cancer did not achieve feasibility targets. Acceptability and perceived effectiveness were moderate, with patient and caregiver participants describing both positive and negative experiences with early specialty palliative care.

These findings must be interpreted in the context of recent trials demonstrating feasibility and efficacy of early specialty palliative care.3,5,20,21 First, it is notable that several larger trials encountered similar enrollment challenges. For example, the consent:approach rate in the ENABLE III trial of early versus delayed initiation of concurrent palliative care was 44%, with a variety of reasons given by approached patients for declining participation.3 Enrolling seriously ill patients in palliative care research is a common challenge and warrants careful consideration of the methods used.

Second, our study included only patients with pancreatic cancer, while other notable trials of outpatient specialty palliative care have included a range of cancer types,3,20,22 included only patients with lung cancer,2 or included patients with lung and gastrointestinal cancers.21 In a trial including patients with lung and gastrointestinal cancer, early integrated palliative care showed differential effects by cancer type: improvements in quality of life were found for patients with lung cancer, but there was no effect for patients with gastrointestinal cancers.21 Additional work is needed to identify the palliative care needs and optimal palliative care delivery models for patients with diverse cancer types, including pancreatic cancer.

Third, higher feasibility in other trials may be related to a difference in clinic structures and/or palliative care integration. For example, a recent trial conducted among advanced pancreatic cancer patients in Italy included only centers that were members of the “Italian Association of Medical Oncology-Palliative Care Working Group” and accredited as “Designated Centres of Integrative Oncology and Palliative Care.”5 This trial demonstrated improved quality of life on physical, functional, and disease-specific subscales with systematic referral to early specialty palliative care, but no significant improvement in overall quality of life (measured using the FACT-Hep) or mood symptoms (measured using the HADS).5

Finally, a recently published systematic review of randomized clinical trials of palliative care interventions found evidence of publication bias.1 It is possible that previous palliative care trials with negative results were not published.

Several insights from this work may inform future palliative care intervention research. First, while enrollment goals were met, our consent:approach and randomized:consent rates were lower than anticipated, and recruitment proceeded more slowly than planned. We encountered several unforeseen enrollment challenges. Over 20% of approached patients declined participation, most often because they were simply too tired or overwhelmed at the time of diagnosis to contemplate participation. Finding a time to discuss the study with patients during a busy clinic visit in which they were also receiving bad news and meeting with multiple new physicians proved difficult. Approaching potential palliative care research participants at a subsequent oncology treatment visit, rather than at the time of initial diagnosis, may decrease patient and caregiver burden, minimize disruptions to clinic flow, and increase participation rates.

In addition, even at an academic cancer center where outpatient palliative care services were available, nearly 30% of approached patients lacked ongoing access to these specialists (and were therefore ineligible) because they planned to return to their local oncology practices without outpatient specialty palliative care. Broadening participation in palliative care trials and clinical access to palliative care services will require interventions that can be more widely and easily disseminated to the majority of patients with cancer who do not receive ongoing oncology care at academic cancer centers. Telephone- and video teleconferencing-based palliative care interventions hold promise for increasing access to specialty palliative care.3,4,23

Second, participant attendance at palliative care visits was fairly low. In process interviews, patients and caregivers cited scheduling difficulties, living far away with long travel times to the cancer center, and spending too long at the cancer center and in the sick role as negative aspects of participation that interfered with specialty palliative care visit attendance. Despite every effort to accommodate patient and caregiver scheduling requests, conflicting physician schedules did not always permit oncology and palliative care visits to be scheduled on the same day. Of note, study participants were not charged co-pays for palliative care visits and were reimbursed to cover travel expenses; it is possible that visit participation would have been even lower without these accommodations.

In addition, patient and caregiver participants, as well as palliative care physicians, commented that visits were sometimes conducted despite an absence of clear palliative care needs. This finding correlates with data from a large cluster-randomized trial of early palliative care conducted in Canada, in which lack of symptoms was a barrier to participation in the group assigned to receive monthly palliative care visits.20 Tailoring the frequency and content of palliative care visits to match identified needs may improve patient and caregiver experiences with palliative care and increase participation in palliative care research.

Finally, despite efforts to facilitate e-mail communication between oncologists and palliative care physicians, many clinician participants noted that in-person communication would improve patient care. Oncologists suggested embedding palliative care providers in disease-specific oncology clinics and palliative care clinician participation in oncology preclinic conferences. Structured communication between oncologists and palliative care specialists can be achieved through care management strategies (e.g., interdisciplinary team meetings).24 These arrangements may increase acceptance of palliative care as part of a team-based approach to advanced cancer, promote trust between oncologists and palliative care clinicians, ensure that patients are not receiving mixed messages about prognosis or treatment goals, and promote knowledge and skills dissemination between oncologists and palliative care clinicians. However, such a multidisciplinary approach requires flexible staffing and reimbursement models for clinicians who are not directly delivering patient care.

This study involved several limitations. First, the trial was conducted at a single academic cancer center among predominantly Caucasian patients with high educational and socioeconomic status. Findings may not generalize to more diverse patients receiving care in other settings. Second, we did not administer a palliative care needs assessment and are therefore unable to comment on the extent to which absence of perceived palliative care needs was a barrier to palliative care visit participation. Third, the palliative care intervention was delivered by a specialty palliative physician alone. Recent guidelines recommend interdisciplinary palliative care teams as the most effective way to care for patients with advanced cancer.6 Fourth, our outcome assessments did not allow us to assess potential associations between symptom burden or anticancer treatment regimens and quality of life. Finally, distributing the intervention manual to all participating oncologists may have introduced contamination in the control arm.

In summary, we describe feasibility, acceptability, and perceived effectiveness findings from a pilot trial of early specialty palliative care for pancreatic cancer. Our experience illustrates the challenges of developing and evaluating palliative care interventions that meet the needs of patients with advanced cancer, their caregivers, oncologists, and palliative care clinicians. Attention to accessibility and potential for dissemination of palliative care services, minimizing participant burden, flexible intervention designs that match patient and caregiver needs, and promoting and supporting interdisciplinary, team-based care is needed in future intervention trials.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Charity Moore Patterson, PhD, MSPH; Seo Young Park, PhD; and Douglas B. White, MD, MAS, for their contributions to this article. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number KL2TR000146. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This project used the UPCI that is supported, in part, by award P30CA047904.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Kavalieratos D, Corbelli J, Zhang D, et al. : Association between palliative care and patient and caregiver outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2016;316:2104–2114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. : Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:733–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bakitas MA, Tosteson TD, Li Z, et al. : Early versus delayed initiation of concurrent palliative oncology care: Patient outcomes in the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:1438–1445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dionne-Odom JN, Azuero A, Lyons KD, et al. : Benefits of early versus delayed palliative care to informal family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer: Outcomes from the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:1446–1452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maltoni M, Scarpi E, Dall'Agata M, et al. : Systematic versus on-demand early palliative care: Results from a multicentre, randomised clinical trial. Eur J Cancer 2016;65:61–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, et al. : Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:96–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schenker Y, Crowley-Matoka M, Dohan D, et al. : Oncologist factors that influence referrals to subspecialty palliative care clinics. J Oncol Pract 2014;10:e37–e44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang VT, Hwang SS, Feuerman M: Validation of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale. Cancer 2000;88:2164–2171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vitek L, Rosenzweig MQ, Stollings S: Distress in patients with cancer: Definition, assessment, and suggested interventions. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2007;11:413–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bedard M, Molloy DW, Squire L, et al. : The Zarit Burden Interview: A new short version and screening version. Gerontologist 2001;41:652–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrell B, Connor SR, Cordes A, et al. : The national agenda for quality palliative care: The National Consensus Project and the National Quality Forum. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007;33:737–744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barnato AE, Schenker Y, Tiver G, et al. : Storytelling in the early bereavement period to reduce emotional distress among surrogates involved in a decision to limit life support in the ICU: A pilot feasibility trial. Crit Care Med 2017;45:35–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heffernan N, Cella D, Webster K, et al. : Measuring health-related quality of life in patients with hepatobiliary cancers: The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Hepatobiliary questionnaire. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:2229–2239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steinhauser KE, Clipp EC, Bosworth HB, et al. : Measuring quality of life at the end of life: Validation of the QUAL-E. Palliat Support Care 2004;2:3–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mack JW, Nilsson M, Balboni T, et al. : Peace, Equanimity, and Acceptance in the Cancer Experience (PEACE): Validation of a scale to assess acceptance and struggle with terminal illness. Cancer 2008;112:2509–2517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP: The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lowe B, Unutzer J, Callahan CM, et al. : Monitoring depression treatment outcomes with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9. Med Care 2004;42:1194–1201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barry LC, Kasl SV, Prigerson HG: Psychiatric disorders among bereaved persons: The role of perceived circumstances of death and preparedness for death. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2002;10:447–457 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK, Reynolds CF, 3rd, et al. : Inventory of Complicated Grief: A scale to measure maladaptive symptoms of loss. Psychiatry Res 1995;59:65–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. : Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014;383:1721–1730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Temel JS, Greer JA, El-Jawahri A, et al. : Effects of early integrated palliative care in patients with lung and GI cancer: A randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol 2016;35:834–841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. : Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: The Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009;302:741–749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.White C, McIlfatrick S, Dunwoody L, Watson M: Supporting and improving community health services-a prospective evaluation of ECHO technology in community palliative care nursing teams. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2015. [Epub ahead of print.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abernethy AP, Currow DC, Shelby-James T, et al. : Delivery strategies to optimize resource utilization and performance status for patients with advanced life-limiting illness: Results from the “palliative care trial” [ISRCTN 81117481]. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013;45:488–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]