Abstract

Background: Care at the end of life is increasingly fragmented and is characterized by multiple hospitalizations, even among patients enrolled with hospice.

Objective: To determine whether hospice spending on direct patient care (including the cost of home visits, drugs, equipment, and counseling) is associated with hospital utilization and Medicare expenditures of hospice enrollees.

Design: Longitudinal, observational cohort study (2008–2010).

Setting/Subjects: Medicare beneficiaries (N = 101,261) enrolled in a national random sample of freestanding hospices (N = 355).

Measurements: We used Medicare Hospice Cost reports to estimate hospice spending on direct patient care and Medicare claim data to estimate rates of hospitalization and Medicare expenditures.

Results: Hospice mean direct patient care costs were $86 per patient day, the largest component being patient visits by hospice staff (e.g., nurse, physician, and counselor visits). After case-mix adjustment, hospices spending the most on direct patient care had patients with 5.2% fewer hospital admissions, 6.3% fewer emergency department visits, 1.6% fewer intensive care unit stays, and $1,700 less in nonhospice Medicare expenditures per patient compared with hospices spending the least on direct patient care (p < 0.01 for each comparison). Ninety percent of hospices with the lowest spending on direct patient care and highest rates of hospital use were for-profit hospices.

Conclusions: Patients cared for by hospices with lower direct patient care costs had higher hospitalization rates and were overrepresented by for-profit hospices. Greater investment by hospices in direct patient care may help Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services avoid high-cost hospital care for patients at the end of life.

Keywords: : costs, end-of-life transitions, for-profit hospice, hospice, Medicare expenditures

Introduction

Care at the end of life is increasingly fragmented. As described in the Institute of Medicine's recent report,1 individuals at the end of life often experience preventable hospitalizations, high-intensity burdensome treatments, and problematic healthcare transitions.2–5 Numerous studies indicate that the majority of individuals in the United States prefer not to have intensive hospital-based care when they die6,7 and would prefer to die at home.8–10 Yet, during the past decade, the proportion of patients who use intensive care units (ICU) in the last month of life has increased from 24% to 29%; the mean number of healthcare transitions in the last 90 days of life increased from 2.1 to 3.1 per decedent; and the percentage of patients experiencing transitions in the last three days of life increased from 10% to 14%.11 Transitions to the hospital at the end of life can lead to nonbeneficial interventions, medical errors, injuries, and adverse reactions for patients.12–14 Even for individuals who enroll with hospice, healthcare transitions are common.15–17 An estimated 18% of hospice enrollees have emergency department (ED) visits, and 13% of patients are admitted to a hospital.15 These transitions, including those that result in the patient's death in the hospital setting, are both expensive and widely recognized as indicators of poor quality end-of-life care.

Our previous work identified considerable variation across hospice providers in the hospitalization rates of their patients, even after accounting for differences in case mix.15 Understanding the source of this variation is important as it may indicate differential responses to financial incentives inherent in how Medicare reimburses hospices. Under the Medicare Hospice Benefit, hospices provide all care related to a hospice enrollee's terminal illness and are then reimbursed by Medicare by a fixed per diem payment regardless of the intensity of patient care or number of patient visits. When hospice enrollees are hospitalized or visit the ED, however, Medicare (rather than the hospice) generally pays for the patient's care. We hypothesized that patients cared for by hospices that provide less (vs. more) intensive direct patient care (e.g., fewer and/or less comprehensive home visits) have higher hospitalization rates, more ED visits, more ICU stays, higher hospice disenrollment rates, and are more likely to die in the hospital. In this way, hospices that provide less intensive direct patient care during the hospice stay may be “shifting” costs of care from their own budgets to Medicare.

We sought to examine the association between hospice spending on direct patient care and rates of hospital admission, ED visits, ICU stays, hospice disenrollment, hospital death, and total average per patient Medicare expenditures. Direct patient care costs consist of the cost of patient visits (including hospice staffing costs) and the cost of drugs, equipment, and counseling (including spiritual and dietary counseling). We used data from a longitudinal cohort study (2009–2011) of Medicare beneficiaries (N = 101,261) enrolled with a national random sample of freestanding hospices (N = 355) and linked to data from Medicare hospice cost reports. Findings from this study may inform the development of hospice-led interventions to reduce hospitalizations following hospice enrollment, which may also help cost shifting by hospices to Medicare and may have implications for patient quality.

Methods

Study design and sample

We used data for all freestanding hospices that responded to our previously completed National Hospice Survey (84% response rate, as described elsewhere)15,18–20 linked to data from Medicare claims and Medicare hospice cost reports. We defined our patient sample to include Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries aged 66 or older who were newly enrolled in National Hospice Survey respondent hospices between September 2008 and November 2009 and were followed until death. We included only freestanding hospices because hospices affiliated with hospitals and other healthcare organizations do not submit Medicare hospice cost reports.

Data sources and variable construction

We obtained data regarding hospice costs from the Healthcare Cost Report Information System (HCRIS), which maintains the Medicare hospice cost reports submitted annually by all freestanding hospices that participate in the Medicare Hospice Benefit. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Provider Reimbursement Manual Part I (HCFA Pub. 15-I), Chapter 38 provides a detailed description of the cost data that freestanding hospices are required to complete. We used the 2009 Hospice Cost Report for each hospice in our sample. We defined hospice-level direct patient care costs as the sum of costs for visiting services (defined as the cost of providing patient visits across thirteen labor disciplines, including physician services, nursing care, physical therapy, spiritual counseling, dietary counseling, and in both home and inpatient hospice settings) and other hospice services (including costs for drugs, durable medical equipment and supplies, imaging services, and laboratory services in both home and inpatient hospice settings). Indirect hospice costs include costs for buildings, fixtures, equipment, administration, volunteer program costs, and bereavement program costs. We calculated each hospice's average direct patient care costs per patient day (PPD; and total costs ppd) by dividing the direct patient care costs (or total costs) by the hospice's number of patient-days reported on worksheet S1 of the cost report.

We used Medicare claim data to estimate each hospice's average total Medicare expenditures per patient from hospice enrollment to death and the proportion of patients with one or more hospital admissions, ED visits, and ICU stays, the proportion of patients who disenrolled from hospice, and the proportion of patients who die in the hospital.

We used several data sources to risk-adjust hospice-level outcomes for differences in patient populations. We used patient-level Medicare claim data linked to our National Hospice Survey data to characterize hospice patient population by age, gender, race, number of chronic conditions, and the following primary diagnoses based on International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes: cancer, diseases of the circulatory system, mental disorders, diseases of the respiratory system, symptoms, signs, and ill-defined conditions. We used hospice cost reports (described above) to obtain each hospice's total annual number of patient-days, which reflects both patient volume and enrollment duration. We used data from the National Hospice Survey regarding the hospice's geographic location (e.g., region), proportion of patients served in the nursing home setting, ownership, size, and chain affiliation.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted at the hospice level. We described the distribution of mean direct patient care costs ppd, mean total costs ppd, and the proportion of direct to total costs ppd across all sampled hospices and by hospice characteristics. We categorized hospices into quartiles based on the distribution of direct patient care costs.

We estimated the unadjusted and adjusted associations between quartile of direct patient care costs ppd and the proportion of patients with hospital admission, ED visits, ICU stays, hospice disenrollment, and hospital death using fractional logit models,21,22 which account for the bounded nature of proportional outcomes. We also estimated the adjusted proportions of hospital admission and ED visits by quartile of direct patient care costs ppd separately for for-profit and nonprofit hospices using fractional logit models.21,22

We estimated the unadjusted and adjusted associations between quartile of direct patient care costs ppd and average total Medicare expenditures per patient and average Medicare expenditures per patient excluding hospice care using generalized linear models with a gamma distribution and log link consistent with recommended methods for modeling healthcare cost data.23

All multivariable models included the following patient population characteristics identified in prior research15 to be associated with study outcomes: average age of the population, percent female, percent white race, average number of chronic conditions, percent served in the nursing home, region, annual number of patient-days, and percent of patients with each of the following primary diagnoses: cancer, diseases of the circulatory system, mental disorders, diseases of the respiratory system, and symptoms, signs, and ill-defined conditions.

We performed analyses using Stata software, version 14. All reported p values are two-sided with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant. This study was exempt from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai's Institutional Review Board.

Results

Our sample comprised 101,261 patients who were cared for by 355 freestanding hospices during the period 2008–2010. Approximately two-thirds of hospices were for-profit, one-third of hospices were part of a chain of hospices, three-quarters were located in an urban area, and approximately half of hospices had fewer than 50 patients per day on average (Table 1). The hospice-level patient population characteristics include a mean age of 82.9 years (standard deviation [SD] 1.9 years), 60.4% female, 28.1% with a primary diagnosis of cancer, and 29.0% cared for in the nursing home setting (Table 1). The patients in sampled hospices had average and median enrollment duration of 83.0 days (SD 143.9) and 18.0 days, respectively. Across sampled hospices, the average hospitalization rate after hospice enrollment was 15.8% (SD 12.7%, interquartile range [IQR] 7.2%–20.1%), the proportion of patients with at least one ED visit was 22.0% (SD 14.0%, IQR 12.5%–27.8%), the proportion with an ICU stay was 5.1% (SD 6.0%, IQR 1.4%–6.3%), the proportion who disenrolled from hospice was 22.0% (SD 15.3%, IQR 11.9%–27.7%), and 2.8%, on average, died in the hospital (SD 3.9%, IQR 0.8%–3.4%). Hospice-level patient population characteristics by direct patient care costs are shown in the Appendix Table A1.

Table 1.

Hospice and Patient Population Characteristics

| Hospice characteristics (N = 355) | N (%) |

| Hospice ownership | |

| For-profit | 242 (68) |

| Nonprofit | 110 (31) |

| Size (patients per day) | |

| <20 | 73 (21) |

| 20–49 | 87 (25) |

| 50–99 | 102 (29) |

| ≥100 | 93 (26) |

| Chain affiliation | |

| Chain | 113 (32) |

| Location | |

| Urban | 270 (76) |

| Suburban/rural | 85 (24) |

| Region | |

| New England/Middle Atlantic | 33 (10) |

| North Central | 68 (20) |

| South Atlantic | 65 (18) |

| South Central | 131 (37) |

| Mountain/Pacific | 58 (16) |

| Patient population characteristics (N = 101,261) | Mean (SD) |

| Age | 82.9 (1.9) |

| Percent female | 60.4 (7.9) |

| Percent white | 85.2 (16.4) |

| Primary diagnosis | |

| Cancer | 28.1 (11.6) |

| Diseases of the circulatory system | 20.8 (8.4) |

| Symptoms, signs, and ill-defined conditions | 17.3 (10.6) |

| Mental disorders | 9.6 (7.7) |

| Diseases of the respiratory system | 9.0 (4.5) |

| Percent cared for in a nursing home | 29.0 (21.7) |

| Number of chronic conditions | 5.3 (0.7) |

SD, standard deviation.

Hospice costs ppd

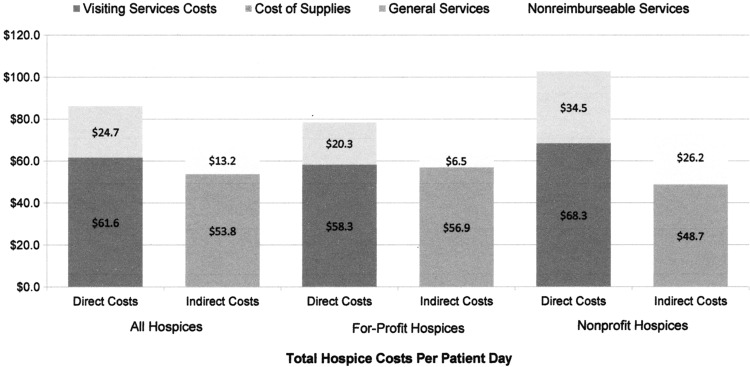

Mean direct patient care costs ppd were $86 (SD 38), median $78, and IQR $62–$102. Hospices in the highest quartile of spending on direct patient care costs ppd spent 2.6 times more than hospices in the lowest quartile of spending ($135 vs. $51). The largest component of direct patient care costs ppd was the cost of patient visits (Fig. 1). The mean cost of visits ppd was $61.6 (SD 31.5), median $55.1, and IQR $45.2–$70.5. On average, direct costs ppd comprised 57.8% (SD 13.0%) of total costs ppd for hospices. The median for this proportion was 57.9% (IQR: 49.4%–67.2%). For for-profit hospices, the mean cost of visits ppd was $58.3 (SD 34.0), median $51.4, and IQR $43.0–$63.7, and for nonprofit hospices, the mean cost of visits ppd was $68.3 (SD 23.8), median $66.8, and IQR $51.9–$79.1 (Fig. 1)

FIG. 1.

Components of total hospice costs per patient day (N = 355 hospices).

Direct patient care costs ppd, total costs ppd, and the proportion of direct patient care costs to total costs significantly differed by hospice characteristics (Table 2). Direct patient care costs ppd were significantly higher for nonprofit hospices, larger hospices, hospices in urban areas, and hospices in the New England/Middle Atlantic region. Similarly, the proportion of direct to total costs ppd was higher for nonprofit hospices, larger hospices, and hospices in New England/Middle Atlantic.

Table 2.

Hospice Direct Patient Care Costs and Total Costs per Patient Day

| Mean direct costs ppd, $ (SD) | Mean total costs ppd, $ (SD) | Direct to total costs ppd, % (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All hospices | 86.3 (38.2) | 153.3 (76.5) | 0.58 (0.13) |

| Hospice ownership | |||

| For-profit | 78.6 (38.1) | 142.0 (58.8) | 0.56 (0.12) |

| Nonprofit | 102.8 (32.7)* | 177.7 (102.3)* | 0.62 (0.14)* |

| Size (patients per day) | |||

| <20 (Reference) | 74.9 (30.8) | 155.1 (118.5) | 0.54 (0.17) |

| 20–49 | 84.6 (45.3) | 156.5 (76.5) | 0.55 (0.13) |

| 50–99 | 87.8 (41.0)** | 148.6 (63.3) | 0.59 (0.11)* |

| ≥100 | 95.3 (30.0)* | 153.9 (40.6) | 0.62 (0.10)* |

| Chain affiliation | |||

| Chain | 81.5 (43.8) | 144.8 (56.3) | 0.56 (0.10) |

| Not chain | 88.6 (35.1) | 157.2 (84.1) | 0.59 (0.14)** |

| Location | |||

| Urban | 90.0 (40.0) | 159.9 (83.8) | 0.58 (0.13) |

| Suburban/rural | 74.7 (28.7)* | 132.3 (40.2)* | 0.57 (0.14) |

| Region | |||

| New England/Middle Atlantic | 109.4 (71.7)* | 194.6 (175.1)* | 0.64 (0.16)** |

| North Central | 87.7 (34.4) | 155.8 (60.9) | 0.57 (0.12) |

| South Atlantic (reference) | 81.6 (31.1) | 144.2 (47.8) | 0.57 (0.13) |

| South Central | 80.6 (33.1) | 144.6 (61.0) | 0.57 (0.13) |

| Mountain/Pacific | 89.9 (27.7) | 156.5 (49.6) | 0.59 (0.12) |

p < 0.01; **p < 0.05 for comparison using unadjusted generalized linear model with a gamma distribution and log link for comparisons of mean costs ppd and fractional logit models for comparisons of proportions.

ppd, Per patient day.

Direct patient care costs and hospitalization rates and Medicare expenditures

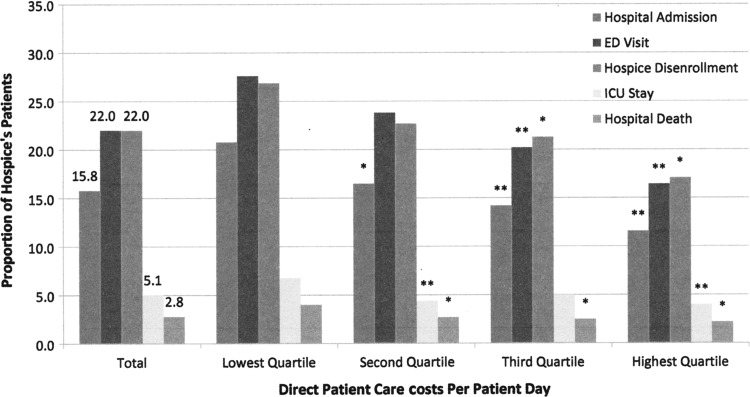

The proportions of patients who were hospitalized, had an ED visit, ICU stay, disenrolled from hospice, and experienced a hospital death, by quartile of hospice direct patient care costs, are shown in Figure 2. Unadjusted total average Medicare expenditures ranged from $26,400 per person for hospices in the lowest quartile of direct patient care costs to $16,500 per person for hospices in the highest quartile; total average nonhospice Medicare expenditures ranged from $8,000 per person for hospices in the highest quartile of direct patient care costs to $4,800 per person in the lowest quartile. In both unadjusted analyses and analyses adjusted for patient mix, hospices with the lowest spending on direct patient care had significantly higher rates of hospital admission and ED visits and higher total Medicare expenditures and nonhospice Medicare expenditures (Table 3). In adjusted analyses, hospices with the lowest spending on direct patient care had patients with total Medicare expenditures that were $6,200 higher (and nonhospice Medicare expenditures that were $1,700 higher) than patients at hospices with the highest spending on direct patient care. Ninety percent of hospices in the lowest quartile of spending on direct patient care were for-profit owned, and only 14% of for-profit hospices are in the highest quartile of spending on direct patient care.

FIG. 2.

Proportion of patients with hospital utilization and hospice disenrollment by quartile of hospice direct patient care costs (N = 355 hospices). Fractional logit model across direct patient care cost quartiles. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 compared with the lowest quartile.

Table 3.

Healthcare Use by Hospice Enrollees Cared for by Hospices with Lower and Higher Direct Patient Care Costs (N = 355 Hospices)

| Direct costs ppd quartile 1 (lowest), N = 88 | Direct costs ppd quartile 2, N = 90 | Direct costs ppd quartile 3, N = 89 | Direct costs ppd quartile 4 (highest), N = 88 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted measure of usea | ||||

| Total Medicare expenditures | 24,219 | 21,970 | 20,252* | 18,013* |

| Total nonhospice Medicare expenditures | 7,215 | 6,681 | 5,716 | 5,535** |

| Proportion with hospital admission | 0.18 | 0.16** | 0.14* | 0.13* |

| Proportion with ED visit | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.20* | 0.19* |

| Proportion with ICU stay | 0.06 | 0.04* | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| Proportion who disenroll from hospice | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 |

| Proportion dying in the hospital | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

Reference group for each comparison is direct costs ppd quartile 1.

p < 0.01; **p < 0.05.

Adjusted for patient population characteristics: average age, percent female, percent white race, average number of chronic conditions, percent served in a nursing home, region, annual number of patient-days, and percent with each of the following primary diagnoses: cancer, diseases of the circulatory system, mental disorders, diseases of the respiratory system, and symptoms, signs, and ill-defined conditions.

ED, emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit.

Discussion

We found that hospices that spent more on direct patient care costs (e.g., patient visits, drugs, and supplies) had lower rates of hospitalization of their patients and lower Medicare expenditures per patient. After adjusting for case-mix differences, hospices spending the most on direct patient care had patients with 5.2% fewer hospital admissions, 6.3% fewer ED visits, and 1.6% fewer ICU stays. With greater investment by hospices in direct patient care, CMS could yield potential savings through lower hospital use. Specifically, CMS pays $1,700 more per patient for care outside of the Medicare Hospice Benefit for patients of hospices who spend the least on direct patient care.

From a quality perspective, these results suggest that greater investment by hospices in direct patient care may improve the quality of care at the end of life by reducing transitions to the hospital. Our prior work15 found that greater use of hospice preferred practices—namely assessing patient preferences for site of death at hospice admission and more frequently monitoring symptoms of home hospice patients—was associated with lower rates of hospitalization; however, the present study is the only study of which we know that establishes higher investment in direct patient care during hospice which may confer financial savings in hospital care. Some of the reasons for hospitalization after hospice enrollment (e.g., difficulty managing symptoms, reluctance to administer opioids, and caregiver burden) would appear to be amenable to hospice intervention. The National Quality Forum's Framework and Preferred Practices for Palliative and Hospice Care Quality24 emphasizes the importance of educating families on what to expect and how to manage symptoms during the last hours of life. Taken together, these results suggest that the substantial variation across hospices in the rates at which patients are hospitalized may be at least partially explained by the type and intensity of the services provided to patients and families.

From a financial perspective, these results also suggest that some hospices may be “shifting” the cost of patient care from their own budget to the Medicare program. Hospices that spent less on direct patient care for services such as home visits and medications had higher proportions of patients hospitalized and entering the ED, which is generally reimbursed by Medicare (not the hospice). The combination of per diem hospice reimbursement and hospitalizations that are paid by Medicare creates a financial disincentive for high-quality hospice care. As long as patients with complex needs can be easily shifted back to Medicare Part A, hospice providers have little economic incentive to reduce hospital use. We found that for-profit hospices are disproportionately represented in the quartile of hospices with the lowest spending on direct patient care and the highest rates of hospital use and Medicare expenditures. These findings underscore the need to monitor potential cost shifting among for-profit hospices, particularly given their increasing market share.25,26 Policy changes related to how acute care for individuals enrolled with hospice is paid may mitigate this underlying incentive for hospital use and help curb spending by CMS for hospice enrollees.

Initiatives by CMS to track hospice quality metrics provide greater insight into the link between direct patient care and hospitalizations of hospice enrollees. In 2010, CMS required that hospices report the frequency and duration of patient visits by professional staff, as well as the type of hospice staff who conduct these visits. The first analyses of these data estimate that 12.3% of hospice enrollees received no professional staff visits in the last two days of life.11 The next step in CMS regulatory oversight of hospices should be to consider as quality metrics for hospices the proportion of patients who visit the ED and who are admitted to the hospital with the goal of providing an incentive to reduce avoidable hospitalizations. Such quality metrics, coupled with clinical quality metrics, including the comfortable dying measure recently endorsed by the National Quality Forum and the perspective of bereaved family members regarding their hospice experience, would together yield a more comprehensive picture of the quality of hospice care and its variation across providers in the United States.

There are several limitations to our study. One is that we lack patient-level data on hospice care, including the frequency with which visits and clinical care processes were received by patients. We also do not know the content of patient and family preferences for care and thus the congruence of hospitalization outcomes with care preferences; however, we would expect preferences regarding hospital use to be fairly evenly distributed across hospices. Similarly, we do not have data on other important patient and family outcomes, such as satisfaction with care, pain and other symptoms, and quality of life. Given that our study is observational, there may be unmeasured confounders such as socioeconomic status and extent of informal caregiving; however, we have included a fairly comprehensive set of patient demographic and clinical characteristics to risk-adjust the hospice-level outcomes in the multivariable models. Our dataset lacks separate variables for patient volume and enrollment duration for the entire hospice patient population; however, we include the covariate patient-days, which capture both patient volume and enrollment duration in a single measure. Finally, our results are not generalizable to the ∼7% of hospices in the United States that do not participate in the Medicare program,26 the 40% of hospices that are not freestanding,26 and the 15% of hospice users whose payment source is not the Medicare Hospice Benefit.26

Greater spending by hospices on direct patient care is associated with higher quality of care for patients and families as measured by hospitalization rates for patients at the end of life, including hospital admission, ED visits, and ICU stays. Considerable variation across hospices in Medicare spending and hospitalization rates, even after adjusting for case mix, may signal that patient and family needs are not being met equally across hospice providers. Our study also sheds light on the possible extent to which hospices shift the cost of services from their own budget to Medicare's with implications for patient quality of care. Efforts to improve hospice quality through payment reform or regulatory initiatives that incorporate incentives for greater spending by hospices on direct patient care may improve these outcomes, particularly if greater investment is targeted to evidence-based interventions to enable hospice enrollees to remain at home.

Appendix Table A1.

Hospice and Patient Population Characteristics by Direct Patient Care Costs

| Direct costs ppd quartile 1 (lowest) | Direct costs ppd quartile 2 | Direct costs ppd quartile 3 | Direct costs ppd quartile 4 (highest) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospice characteristics (N = 355), N (%) | |||||

| Hospice ownership | |||||

| For-profit | 242 (68) | 79 (90) | 75 (83) | 54 (62) | 34 (39) |

| Nonprofit | 110 (31) | 9 (10) | 15 (17) | 33 (38) | 53 (61) |

| Size (patients per day) | |||||

| <20 | 73 (21) | 24 (27) | 24 (27) | 12 (13) | 13 (15) |

| 20–49 | 87 (25) | 29 (33) | 19 (21) | 22 (25) | 17 (19) |

| 50–99 | 102 (29) | 21 (24) | 33 (37) | 22 (25) | 26 (30) |

| ≥100 | 93 (26) | 14 (16) | 14 (16) | 33 (37) | 32 (36) |

| Chain affiliation | |||||

| Chain | 113 (32) | 36 (41) | 34 (38) | 27 (30) | 16 (18) |

| Location | |||||

| Urban | 270 (76) | 60 (68) | 62 (69) | 73 (82) | 75 (85) |

| Suburban/rural | 85 (24) | 28 (32) | 28 (31) | 16 (18) | 13 (15) |

| Region | |||||

| New England/Middle Atlantic | 33 (10) | 4 (5) | 7 (8) | 7 (8) | 15 (17) |

| North Central | 68 (20) | 19 (22) | 13 (14) | 18 (20) | 18 (20) |

| South Atlantic | 65 (18) | 20 (23) | 14 (16) | 14 (16) | 17 (19) |

| South Central | 131 (37) | 37 (42) | 42 (47) | 29 (33) | 23 (26) |

| Mountain/Pacific | 58 (16) | 8 (9) | 14 (16) | 21 (24) | 15 (17) |

| Patient population characteristics (N = 101,261), mean (SD) | |||||

| Age | 82.9 (1.9) | 82.8 (2.2) | 82.9 (1.8) | 82.9 (1.9) | 83.2 (1.6) |

| Percent female | 60.4 (7.9) | 61.9 (10.6) | 59.6 (6.4) | 59.6 (6.4) | 60.5 (7.5) |

| Percent white | 85.2 (16.4) | 82.4 (19.2) | 87.2 (14.3) | 86.0 (14.6) | 85.0 (16.9) |

| Primary diagnosis | |||||

| Cancer | 28.1 (11.6) | 23.6 (12.1) | 27.5 (10.2) | 28.3 (11.1) | 33.0 (11.1) |

| Diseases of the circulatory system | 20.8 (8.4) | 22.4 (10.5) | 21.1 (6.8) | 20.4 (8.6) | 19.4 (7.1) |

| Symptoms, signs, and ill-defined conditions | 17.3 (10.6) | 18.1 (11.0) | 17.4 (11.3) | 19.2 (10.6) | 14.7 (9.2) |

| Mental disorders | 9.6 (7.7) | 10.0 (9.5) | 9.6 (7.2) | 9.3 (7.0) | 9.4 (7.2) |

| Diseases of the respiratory system | 9.0 (4.5) | 9.4 (5.1) | 9.3 (4.5) | 8.5 (4.1) | 8.9 (4.4) |

| Percent cared for in a nursing home | 29.0 (21.7) | 33.8 (24.1) | 26.6 (21.2) | 26.2 (19.3) | 29.6 (21.6) |

| Number of chronic conditions | 5.3 (0.7) | 5.3 (0.9) | 5.3 (0.6) | 5.2 (0.7) | 5.4 (0.5) |

ppd, Per patient day; SD, standard deviation.

Acknowledgment

This study was funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research 5R0INR013499 (MDA); the National Cancer Institute 1R0ICAH6398-01A (EHB); and the John D. Thompson Foundation (EHB).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.IOM (Institute of Medicine): Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences near the End of Life. National Academies Press, Washington, DC, 2014 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ: The care transitions intervention: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1822–1828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA: Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med 2009;360:1418–1428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teno JM, Gozalo PL, Bynum JP, et al. : Change in end-of-life care for Medicare beneficiaries: Site of death, place of care, and health care transitions in 2000, 2005, and 2009. JAMA 2013;309:470–477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naylor MD, Bowles KH, McCauley KM, et al. : High-value transitional care: Translation of research into practice. J Eval Clin Pract 2013;19:727–733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Field MJ, Cassel CK, eds.: Approaching Death: Improving Care at the End of Life. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnato AE, Herndon MB, Anthony DL, et al. : Are regional variations in end-of-life care intensity explained by patient preferences?: A study of the US Medicare population. Med Care 2007;45:386–393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gallup GH, Jr: Spiritual beliefs and the dying process: A report on a national survey. Conducted for the Nathan Cummings Foundation and the Fetzer Institute. George H. Gallop International Institute, Princeton, NJ, 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higginson IJ, Sen-Gupta GJ: Place of care in advanced cancer: A qualitative systematic literature review of patient preferences. J Palliat Med 2000;3:287–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruera E, Russell N, Sweeney C, et al. : Place of death and its predictors for local patients registered at a comprehensive cancer center. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:2127–2133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teno JM, Plotzke M, Christian T, Gozalo P: Examining variation in hospice visits by professional staff in the last 2 days of life. JAMA Intern Med 2016;170:364–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, et al. : The clinical course of advanced dementia. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1529–1538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gozalo P, Teno JM, Mitchell SL, et al. : End-of-life transitions among nursing home residents with cognitive issues. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1212–1221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Vries EN, Ramrattan MA, Smorenburg SM, et al. : The incidence and nature of in-hospital adverse events: A systematic review. Qual Saf Health Care 2008;17:216–223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aldridge MD, Epstein AJ, Brody AA, et al. : The impact of reported hospice preferred practices on hospital utilization at the end of life. Med Care 2016;54:657–663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang SY, Aldridge MD, Gross CP, et al. : Transitions between healthcare settings of hospice enrollees at the end of life. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016;64:314–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aldridge Carlson MD, Herrin J, Du Q, et al. : Impact of hospice disenrollment on health care use and Medicare expenditures for patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:4371–4375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aldridge Carlson MD, Barry C, Schlesinger M, et al. : Quality of palliative care at US hospices: Results of a national survey. Med Care 2011;49:803–809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aldridge Carlson MD, Barry CL, Cherlin EJ, et al. : Hospices' enrollment policies may contribute to underuse of hospice care in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:2690–2698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barry CL, Aldridge Carlson MD, Thompson JW, et al. : Caring for grieving family members: Results from a national hospice survey. Med Care 2012;50:578–584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Papke LE, Woodldridge JM: Econometric methods for fractional response variables with an application to 401(K) plan participation rates. J Appl Econometr 1996;11:619–632 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baum CF: Stata tip 63: Modeling proportions. Stata J 2008;8:299–303 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buntin MB, Zaslavsky AM: Too much ado about two-part models and transformation? Comparing methods of modeling Medicare expenditures. J Health Econ 2004;23:525–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Quality Forum: A National Framework and Preferred Practices for Palliative and Hospice Care Quality. National Quality Forum, Washington, DC, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thompson JW, Carlson MD, Bradley EH: US hospice industry experienced considerable turbulence from changes in ownership, growth, and shift to for-profit status. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:1286–1293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization: NHPCO Facts and Figures: Hospice Care in America. www.nhpco.org/sites/default/files/public/Statistics_Research/2015_Facts_Figures.pdf 2015. (Last accessed May19, 2017)