Abstract

Purpose

There is only one prior report associating mutations in BEST1 with a diagnosis of retinitis pigmentosa (RP). The imaging studies presented in that report were more atypical of RP and shared features of autosomal recessive bestrophinopathy and autosomal dominant vitreoretinochoroidopathy. Here, we present a patient with a clinical phenotype consistent with classic features of RP.

Observations

The patient in this report was diagnosed with simplex RP based on clinically-evident bone spicules with characteristic ERG and EOG findings. The patient had associated massive cystoid macular edema which resolved following a short course of oral acetazolamide. Genetic testing revealed that the patient carries a novel heterozygous deletion mutation in BEST1 which is not carried by either parent. While this suggests BEST1 is causative, the patient also inherited heterozygous copies of several mutations in other genes known to cause recessive retinal degenerative disease.

Conclusions and Importance

How some mutations in BEST1 associate with peripheral retinal degeneration phenotypes, while others manifest as macular degeneration phenotypes is currently unknown. We speculate that RP due to BEST1 mutation requires mutations in other modifier genes.

Keywords: Retinitis pigmentosa, BEST1, Genetics, Bestrophinopathy

1. Introduction

Mutations in the gene BEST1 (MIM 607854), which encodes the protein Bestrophin-1 (Best1), are responsible for 5 clinically distinct inherited retinopathies: Best vitelliform macular dystrophy (BVMD), adult-onset vitelliform macular dystrophy (AVMD), autosomal recessive bestrophinopathy (ARB), autosomal dominant vitreoretinochoroidopathy (ADVIRC), and retinitis pigmentosa (RP) [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7]. While mutations in BEST1 are widely accepted to cause BVMD, AVMD, ARB, and ADVIRC, there has been only one prior report of mutations in BEST1 causing RP [7]. The clinical images in that paper shared phenotypic features of ARB and ADVIRC, causing some to question whether the subjects in the study have classic RP, and thus, whether BEST1 can cause RP [8].

BEST1 encodes bestrophin 1 (Best1) a homo-oligomeric anion channel that, within the eye, is exclusively expressed in retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells, where it normally localizes to the basolateral plasma membrane and plays a critical role in regulating Ca2+ signaling [9], [10], [11]. BEST1 mutations are typically thought to be disease-causing when they result in loss of anion-channel activity [12], [13]. Previous studies have shown that the first ∼174 amino acids of Best1 are sufficient to permit oligomerization and that the first ∼366 amino acids are sufficient for both homo-oligomerization and channel activity [14], [15]. It has also been demonstrated that mislocalization alone is not pathogenic [14].

Here, we present a patient with RP due to a deletion mutation in BEST1, H422fsX431.

2. Case report

All patients discussed in this report provided written consent for publication of personal information, including details from their medical records and photographs. A 16-year-old male with longstanding history of nyctalopia and constricted peripheral vision was evaluated by the retina service at Mayo Clinic after referral from a facility in Denmark. His best-corrected distance visual acuity with the prescription −1.00 + 1.25 × 93 in the right eye and +0.25 + 1.00 × 100 in the left eye was 0.2 logMAR (20/32) in both eyes. Intraocular pressures were 10 and 11 in the right and left eyes, respectively. On slit lamp biomicroscopic exam he was found to have prominent corneal nerves, trace posterior subcapsular cataract, trace to 1+ vitreous cell, massive cystoid macular edema (CME), retinal vascular attenuation (more prominent in the periphery) and extensive bone spicules in both eyes (Fig. 1). CME was further demonstrated on optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging. While OCT revealed mild CME prior to referral (Fig. 2A and B), there was clear progression by the time of examination at Mayo Clinic (Fig. 2C and D). The patient was advised to try treatment with oral acetazolamide for CME, and after 2–3 weeks of treatment with sustained release acetazolamide 250 mg BID (Diamox SR), his CME had nearly resolved (Fig. 2E and F), resulting in visual acuities of 0.3 logMAR (20/40) in the right eye and 0.15 logMAR (20/28) in the left eye. OCT angiography performed at Mayo Clinic was notable for inner retinal microvascular capillary loss and remodeling (Fig. 3).

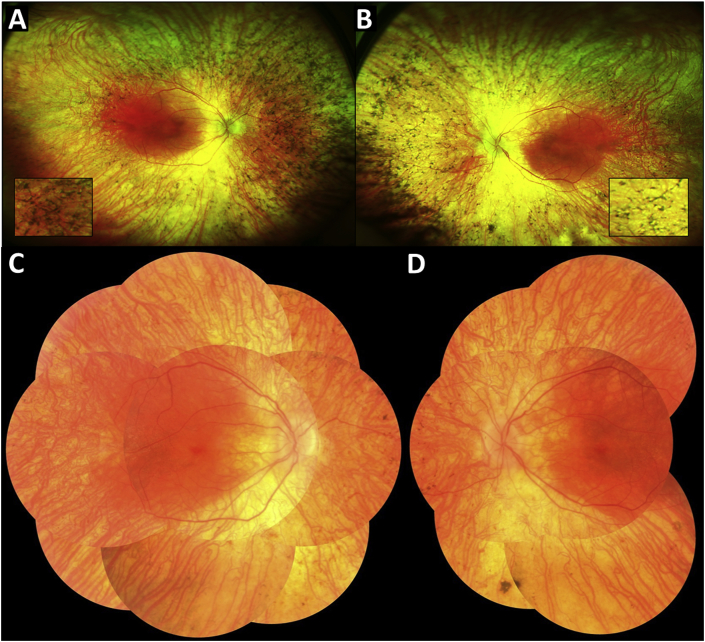

Fig. 1.

Optos ultra-widefield fundus photos of the right (A) and left (B) eyes demonstrate extensive bone spicules and retinal vascular attenuation in the peripheral retina of both eyes. More magnified views of the bone spicules are shown in the insets. Montage color fundus photos of the right (C) and left (D) eyes further support the presence of extensive bone spicules in both eyes.

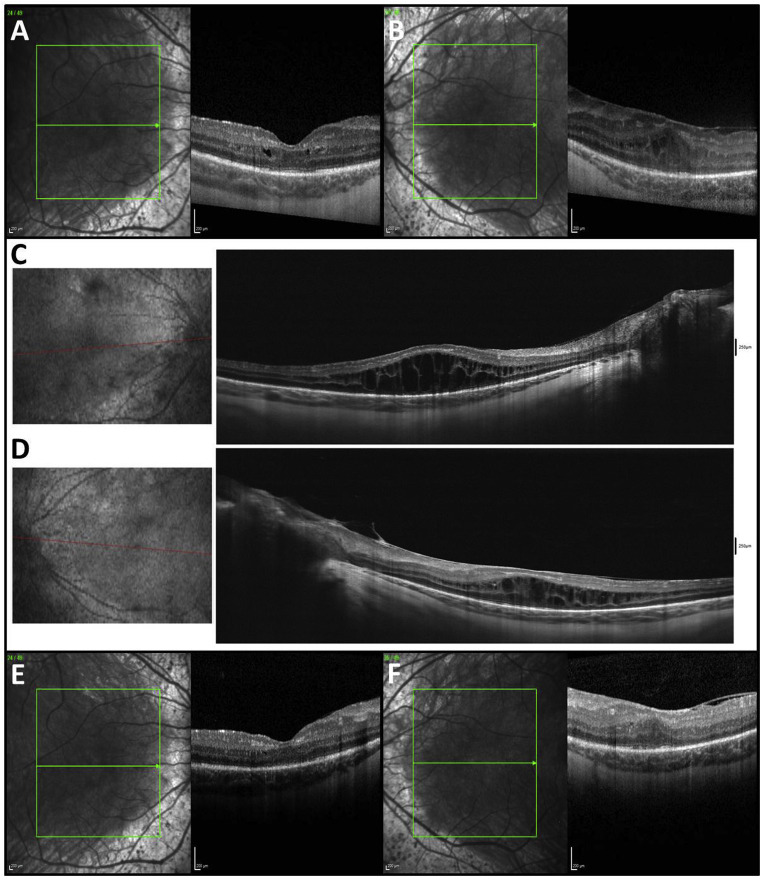

Fig. 2.

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) of the right (A) and left (B) eyes taken in Denmark demonstrates mild cystoid macular edema (CME) in both eyes and epiretinal membrane with mild tractional retinoschisis in the left eye prior to the time of referral. OCT of the right (C) and left (D) eyes taken at Mayo Clinic demonstrates massive CME in both eyes that has progressed since the patient was examined in Denmark. OCT of the right (E) and left (F) eyes taken back in Denmark demonstrates resolution of CME in both eyes after 2–3 weeks of treatment with sustained-release oral acetazolamide 250 mg BID.

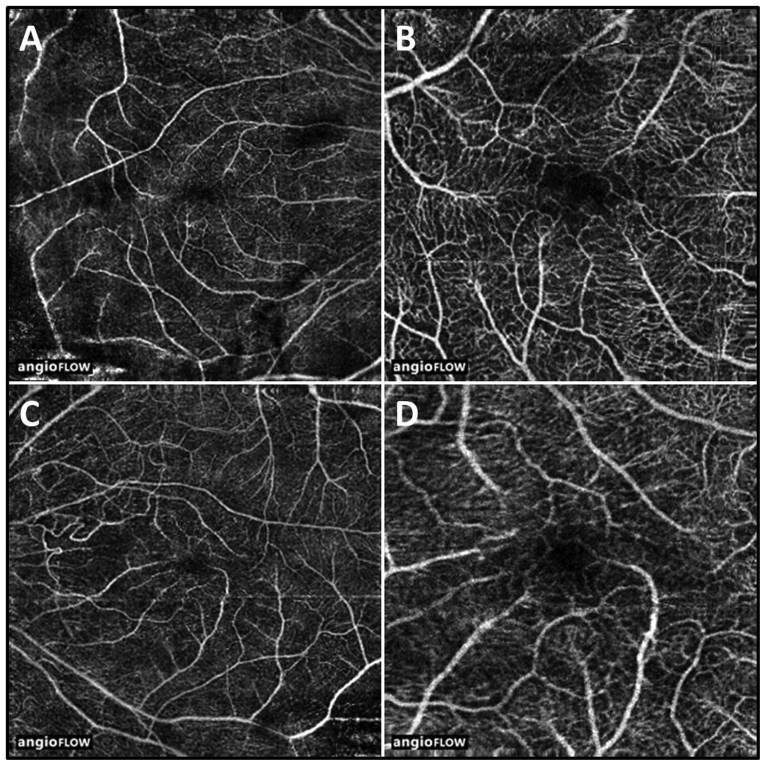

Fig. 3.

Optical coherence tomography angiography of the right (A and B) and left (C and D) eyes reveals inner retinal microvascular capillary loss and remodeling in both eyes.

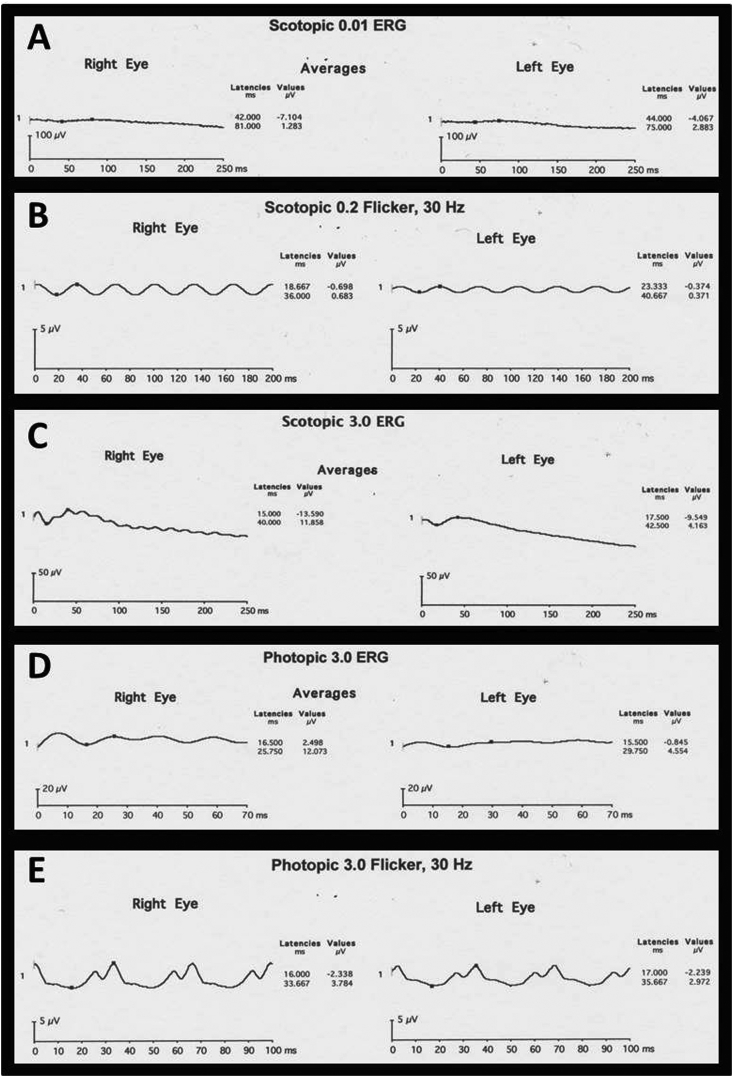

Visual field testing showed generalized constriction to within 20° in both eyes (Fig. 4). Full-field scotopic Ganzfeld ERG testing revealed attenuation of rod and cone responses with trace residual photopic cone responses at 3.0 cd-Sec/M2 and less attenuation of photopic flicker responses. Scotopic 0.2 cd-Sec/M2 flicker showed amplitudes of 1.4 and 0.74 μV with computed attenuation to 0.05 μV equal to 29.9 and 23.9 years, OD and OS, respectively, based upon Berson's observation of exponential decay in this response (Fig. 5). Normative data with ERG testing performed according to International Society for Clinical Electrophysiology of Vision (ISCEV) standards indicate that normal values range as follows: b-wave amplitude 348.96–362.60 μV, b-wave implicit time 49.48–50.49 milliseconds, and a-wave amplitude −234.50 to −231.29 μV for a dark-adapted combined standard flash; b-wave amplitude 261.06–310.41 μV for a dark-adapted dim white light; b-wave amplitude 138.82–141.94 μV for a light-adapted single flash; and implicit time 26.38–26.77 milliseconds for 30-Hz flicker [16], [17]. EOG Arden ratios in both eyes were <1.5. For reference, according to ISCEV standards, Arden ratios >2.0 are considered to be normal; those <1.5 are abnormally low [18]. Based on the sum of these data the diagnosis of simplex retinitis pigmentosa was confirmed.

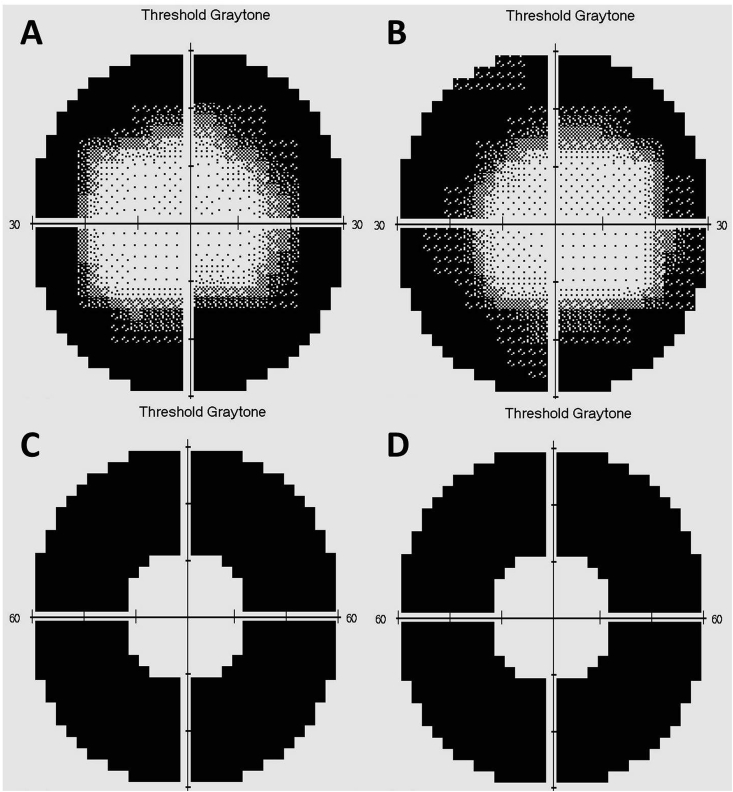

Fig. 4.

Visual field testing (30-2, size V, FASTPAC) in the right (A) and left (B) eyes demonstrates constriction of the visual field within 20° in both eyes. Testing was highly reliable with no fixation losses, false positives, or false negatives in either eye. 60-4 testing using a size V target with FASTPAC algorithm revealed no viable peripheral vision between 30 and 60° in the right (C) or left (D) eyes.

Fig. 5.

Full-field scotopic Ganzfeld electroretinogram (ERG) testing of both eyes (A–C) revealed attenuation of rod responses with depressed amplitudes throughout. Photopic full-field ERG (D–E) showed trace residual cone responses. Scotopic 0.2 cd-Sec/M2 showed diminished responses with time to 0.05 μV predicted at 29.9 years OD and 23.9 years OS.

Of note, the father was also examined and had central serous chorioretinopathy, which is likely unrelated. The parents otherwise had no clinically-evident ocular abnormalities.

Genetic testing was carried out by the University of Oregon, Casey Eye Institute, Molecular Diagnostic Laboratory using a panel of 131 retinal dystrophy genes. A heterozygous deletion of 9348 bases (61729891–61733239) from the BEST1 gene resulting in the mutation H422fsX431 in the proband was identified. The mutation was unique to the proband and absent from both parents who were also tested using the same retinal dystrophy panel. The deletion begins within exon 10 of the BEST1 gene and extends beyond exon 11 resulting in a frame shift causing deletion of 146aa from Best1, and extending into the adjacent ferritin heavy chain (FTH) gene on the opposite strand of DNA. The proband also carried heterozygous mutations in the genes GUCA1A, GPR179, IQCB1, and TRIM32, four genes implicated in other retinal degenerative diseases. These mutations were not considered causative as they were carried by the unaffected parents of the proband as well. It is likely that the deletion from the FTH gene results in a single null allele for FTH. However, at this point the proband has not exhibited any symptoms of ferritin deficiency. Of note, both the father and the proband underwent repeat genetic screening at Mayo Clinic using whole exome sequencing, which confirmed the findings from the Oregon testing.

3. Discussion and conclusions

Here we present a patient with a classic RP phenotype associated with a mutation in BEST1. The prior report on RP due to BEST1 mutation identified missense mutations, some of which were also associated with BVMD, and the clinical phenotype of the patients in that study is somewhat atypical for RP [7]. The patients in the prior study have some clinical features consistent with ARB or ADVIRC [7]. In the present report this subject has a classic clinical phenotype consistent with a diagnosis of dominant RP. The clinical and imaging findings in this report differ significantly from those previously reported for ARB [2], [5], [15], [19], [20]. ARB is a recessive disease in which mutations are present in both BEST1 alleles. While it is possible that we did not detect an intergenic mutation in BEST1, we are unaware of any report of mutations in non-coding regions of BEST1. The proband carries a single wild type allele. From a clinical perspective, ARB affects primarily the macula. Our patient exhibits what is primarily a peripheral retinal dystrophy. All ARB patients exhibit a serous detachment of the macula often with central yellow subretinal deposits, and small yellow deposits ringing the central detachment. These were notably absent in the case presented here [20]. Patients with ARB report central vision loss as an initial symptom with a relatively normal peripheral visual field; in this case peripheral vision was severely affected with central vision remaining intact [20]. Patients with ARB were also reported to be mildly to highly hyperopic; this patient was mildly myopic in the right eye with very slight hyperopia in the left eye [20] While some patients with ARB are reported to have multifocal atrophic lesions or RPE atrophy, none were reported to have bone spicules, a defining characteristic of RP and a prominent feature of this case [20]. Similar to patients with ARB, the patient in this case had an abnormal EOG. However, the ERG was abnormal as well, which can also be seen in ARB [20].

Another possible diagnosis could be ADVIRC. Like RP, ADVIRC is a peripheral retinopathy and is due to dominant mutations in BEST1. However, the fundus in ADVIRC is characterized by well-defined circumferential zones of peripheral hyperpigmentation. Like our proband, however, the ERG can be quite low, and the EOG <1.5 in ADVIRC. Central vision in ADVIRC, when compromised, is often compromised due to CME. The progression of ADVIRC, however, is typically very slow and visual fields are usually not as constricted as in our subject.

The patient in this report also had near complete resolution of his CME after a short course of oral acetazolamide. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors have a well-established role in managing CME, specifically in RP patients [21]. The underlying mechanism of action is thought to be related to carbonic anhydrase inhibitor-driven acidification of the subretinal space that directly results in fluid transport by RPE cells [22]. The excellent response of this patient to acetazolamide further supports his classic RP presentation. However, response to acetazolamide is not specific to RP. In fact, resolution of CME with acetazolamide has previously been reported in a patient with ARB [20].

Mutations in BEST1 like that observed in our subject have been previously reported. Notably, our laboratory identified the mutation I366fsX384 in a subject with ARB and her asymptomatic mother, and larger deletions have also been reported in subjects with ARB and their asymptomatic parents [15], [20], [23], [24]. For the Best1I366fsX384 mutation, Best1 anion channel activity is unimpaired, and recent studies reporting on the structure of Best1 found that the entire anion channel domain of Best1 is contained within the region that is present in Best1 H422fsX431 [25], [26]. For this reason it is unclear how the H422fsX431 mutation could be solely responsible for RP in the proband despite the fact that it is a large de novo mutation that does not occur in either parent.

Interestingly, both parents carry heterozygous mutations in retinal degeneration genes other than BEST1, and some of these mutations have been passed along to the proband. Analysis of the family carrying BEST1I366fsX384 did not reveal similar mutations in any of these genes suggesting the possibility that they may serve as modifiers in our proband. Alternatively, there may be intergenic mutations that went undetected by our sequencing methods, and it is of course possible that other genes we have not examined result in RP when combined with the Best1H422fsX431 mutation. Since there is only a single proband, this is difficult to determine. However, the overlap of reported mutations in BEST1 that segregate with both RP and BVMD in other families suggests the possibility of a digenic or complex genetic cause for RP in these subjects [7]. Future studies should address identification of other genes that may contribute to this phenotype.

Financial support

Supported by an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness Inc, New York, NY., and the Mayo Foundation for Medical Research.

Contributor Information

Lauren A. Dalvin, Email: Dalvin.lauren@mayo.edu.

Jackson E. Abou Chehade, Email: AbouChehade.Jackson@mayo.edu.

John Chiang, Email: chiangj@ohsu.edu.

Josefine Fuchs, Email: helle.josefine.fuchs@regionh.dk.

Raymond Iezzi, Email: Iezzi.Raymond@mayo.edu.

Alan D. Marmorstein, Email: Marmorstein.Alan@mayo.edu.

References

- 1.Marquardt A., Stohr H., Passmore L.A., Kramer F., Rivera A., Weber B.H. Mutations in a novel gene, VMD2, encoding a protein of unknown properties cause juvenile-onset vitelliform macular dystrophy (Best's disease) Hum. Mol. Genet. 1998;7:1517–1525. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.9.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marmorstein A.D., Cross H.E., Peachey N.S. Functional roles of bestrophins in ocular epithelia. Prog. Retin Eye Res. 2009;28:206–226. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petrukhin K., Koisti M.J., Bakall B. Identification of the gene responsible for best macular dystrophy. Nat. Genet. 1998;19:241–247. doi: 10.1038/915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kramer F., White K., Pauleikhoff D. Mutations in the VMD2 gene are associated with juvenile-onset vitelliform macular dystrophy (Best disease) and adult vitelliform macular dystrophy but not age-related macular degeneration. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2000;8:286–292. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burgess R., Millar I.D., Leroy B.P. Biallelic mutation of BEST1 causes a distinct retinopathy in humans. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2008;82:19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yardley J., Leroy B.P., Hart-Holden N. Mutations of VMD2 splicing regulators cause nanophthalmos and autosomal dominant vitreoretinochoroidopathy (ADVIRC) Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2004;45:3683–3689. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davidson A.E., Millar I.D., Urquhart J.E. Missense mutations in a retinal pigment epithelium protein, bestrophin-1, cause retinitis pigmentosa. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2009;85:581–592. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leroy B.P. Bestrophinopathies. In: Traboulsi E.I., editor. Genetic Diseases of the Eye. second ed. Oxford Univ. Press; New York: 2012. p. 434. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marmorstein A.D., Marmorstein L.Y., Rayborn M., Wang X., Hollyfield J.G., Petrukhin K. Bestrophin, the product of the best vitelliform macular dystrophy gene (VMD2), localizes to the basolateral plasma membrane of the retinal pigment epithelium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:12758–12763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.220402097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marmorstein L.Y., Wu J., McLaughlin P. The light peak of the electroretinogram is dependent on voltage-gated calcium channels and antagonized by bestrophin (best-1) J. Gen. Physiol. 2006;127:577–589. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Y., Stanton J.B., Wu J. Suppression of Ca2+ signaling in a mouse model of best disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010;19:1108–1118. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hartzell H.C., Qu Z., Yu K., Xiao Q., Chien L.T. Molecular physiology of bestrophins: multifunctional membrane proteins linked to best disease and other retinopathies. Physiol. Rev. 2008;88:639–672. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00022.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xiao Q., Hartzell H.C., Yu K. Bestrophins and retinopathies. Pflugers Arch. 2010;460:559–569. doi: 10.1007/s00424-010-0821-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson A.A., Lee Y.S., Chadburn A.J. Disease-causing mutations associated with four bestrophinopathies exhibit disparate effects on the localization, but not the oligomerization, of Bestrophin-1. Exp. Eye Res. 2014;121:74–85. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson A.A., Bachman L.A., Gilles B.J. Autosomal recessive bestrophinopathy is not associated with the loss of bestrophin-1 anion channel function in a patient with a novel BEST1 mutation. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2015;56:4619–4630. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-16910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cordell W.H., Maturi R.K., Costigan T.M. Retinal effects of 6 months of daily use of tadalafil or sildenafil. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2009;127:367–373. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCulloch D.L., Marmor M.F., Brigell M.G. ISCEV standard for full-field clinical electroretinography (2015 update) Doc. Ophthalmol. 2015;130:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s10633-014-9473-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marmor M.F., Brigell M.G., McCulloch D.L., Westall C.A., Bach M. ISCEV standard for clinical electro-oculography (2010 update) Doc. Ophthalmol. 2011;122:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s10633-011-9259-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boon C.J., Klevering B.J., Leroy B.P., Hoyng C.B., Keunen J.E., den Hollander A.I. The spectrum of ocular phenotypes caused by mutations in the BEST1 gene. Prog. Retin Eye Res. 2009;28:187–205. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boon C.J., van den Born L.I., Visser L. Autosomal recessive bestrophinopathy: differential diagnosis and treatment options. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:809–820. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fishman G.A., Gilbert L.D., Fiscella R.G., Kimura A.E., Jampol L.M. Acetazolamide for treatment of chronic macular edema in retinitis pigmentosa. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1989;107:1445–1452. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1989.01070020519031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolfensberger T.J. The role of carbonic anhydrase inhibitors in the management of macular edema. Doc. Ophthalmol. 1999;97:387–397. doi: 10.1023/a:1002143802926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Preising M.N., Pasquay C., Friedburg C. Autosomal recessive bestrophinopathy (ARB): a clinical and molecular description of two patients at childhood. Klin. Monbl Augenheilkd. 2012;229:1009–1017. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1327782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borman A.D., Davidson A.E., O'Sullivan J. Childhood-onset autosomal recessive bestrophinopathy. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2011;129:1088–1093. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kane Dickson V., Pedi L., Long S.B. Structure and insights into the function of a Ca(2+)-activated Cl(-) channel. Nature. 2014;516:213–218. doi: 10.1038/nature13913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang T., Liu Q., Kloss B. Structure and selectivity in bestrophin ion channels. Science. 2014;346:355–359. doi: 10.1126/science.1259723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]