Abstract

Background

Croatia implemented individual donation (ID)-NAT testing of blood donors in 2013 for three viruses HBV, HCV, and HIV-1 as a mandatory test for all blood donors. This study assessed the impact of NAT screening 3 years after its implementation.

Methods

A total of 545,463 donations were collected and screened for HBV, HCV, and HIV-1 using the Procleix Ultrio Plus Assay. All initially reactive (IR) NAT samples were retested in triplicate and, if repeatedly reactive (RR), NAT discriminatory assay (dNAT) was performed. ID-NAT positive donations were confirmed by RT-PCR on the COBAS AmpliPrep/TaqMan platform.

Results

Out of 545,463 samples tested, 108 (0.02%) were RR in NAT. There were 82 (75,9%) HBV reactive, 16 (14.8%) HCV reactive, and 10 (9.3%) HIV-1 reactive samples. 51 (47.2%) samples were ID-NAT positive only. Out of these 51 NAT yield cases, 1 window period HIV-1 and 50 occult HBV infections (OBI) were determined. There were only two potential HBV DNA transmissions from OBI donors.

Conclusion

The implementation of NAT screening for three viruses has improved blood safety in Croatia. During the 3-year period, 1 window period HIV-1 and a number of occult HBV donations were identified.

Keywords: Blood donor's screening, NAT testing, Transfusion-transmissible infections

Introduction

The safety of blood and blood components continues to raise debate all over the world. In the past few decades, many measures have been introduced in order to reduce the risk of transmission of blood-borne viruses [1]. In the early 1990s, nucleic acid amplification testing (NAT) expanded rapidly, and blood centers started testing blood units using molecular assays. Before becoming mandatory, it was used on a voluntary basis. Germany was the first country to introduce NAT screening in 1997 on a routine basis, with negative NAT results required prior to the release of blood components. Initially, the methodology included ‘!’ developed semi-automated testing for HBV, HCV, and HIV-1, but NAT screening for HCV and HIV-1 became mandatory in 1999 and 2004, respectively [2, 3]. Several other countries followed Germany and introduced NAT screening primarily for HCV and then for HIV-1 genomes (Austria, Canada, Ireland, Japan, The Netherlands, Spain, Switzerland, the UK, and the USA). Japan and Austria were the first countries that implemented mandatory HBV NAT testing in 1999, followed by global implementation of HBV NAT screening after 2004. The low expected yield and clinical value of interdiction of seronegative HBV infections were the main reason for delayed implementation of HBV NAT [2, 4]. Over years, NAT testing became mandatory in western countries and began to be performed with commercial CE-marked NAT systems in multiplex format, detecting all three viral genomes on automated testing platforms. At the beginning, the majority of countries started NAT testing in minipools (MP-NAT) of 96–16 pooled samples, however, there was progression towards smaller pools of 6 to individual donations (ID) in order to enhance testing sensitivity [5]. Compared to the existing HBsAg assays, MP-NAT reduced the window period (WP) of HBV infection by 9–11 days, and ID-NAT reduced the WP by 25–36 days, which indicates that ID-NAT would have a higher yield than MP-NAT in case of HBV infection. The difference was due to the pooling dilution effect that diminishes assay sensitivity [6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11]. However, MP-NAT strategies are still preferred due to the cost-benefit analysis in some western countries where the prevalence of the tested virus is low. Even though the risk of transfusion-transmitted infections (TTIs) had been reduced significantly by sensitive serologic blood screening and introduction of stringent donor selection criteria in Croatia, the risk of TTIs still persisted. The greatest challenge for transfusion medicine is the risk of HBV transmission due to persistent occult HBV infection (OBI) with very low HBV DNA viremia in which HBsAg is not detectable. For this reason, and based on the Croatian epidemiological situation and analytical/clinical performance data of manufacturers for NAT testing of blood donors, the national blood transfusion committee of Croatia decided to implement mandatory ID-NAT testing in March 2013 as a routine blood screening program, in concordance with serologic screening. The project was implemented as a part of restructuring and centralization of the Croatian blood service. The aim of this study was to evaluate the results of ID-NAT testing during a 3-year period and to analyze the NAT yield rate of HBV, HCV, and HIV-1 screening in Croatia.

Material and Methods

Collection of Blood Donor Samples and Delivering to the Croatian Institute of Transfusion Medicine

All blood donations collected at the blood centers and mobile units across Croatia in the period from March 1, 2013 until March 1, 2016 were donated by voluntary non-remunerated blood donors. Serology and ID-NAT tests were performed concurrently using two different samples. Testing was performed at the Croatian Institute of Transfusion Medicine (CITM), Department of Molecular Diagnosis in Zagreb, the only NAT testing site in Croatia using the Procleix Ultrio Plus Assay on three Procleix Tigris System instruments (Grifols, Spain). Test results were then distributed through the e-Delphyn, national transfusion IT system that interconnects all 8 blood centers (Split, Dubrovnik, Osijek, Rijeka, Pula, Varaždin, Zadar, and Zagreb) in Croatia.

ID-NAT Testing Methodology, Algorithm at the Croatian Institute of Transfusion Medicine and Residual Risk Calculation

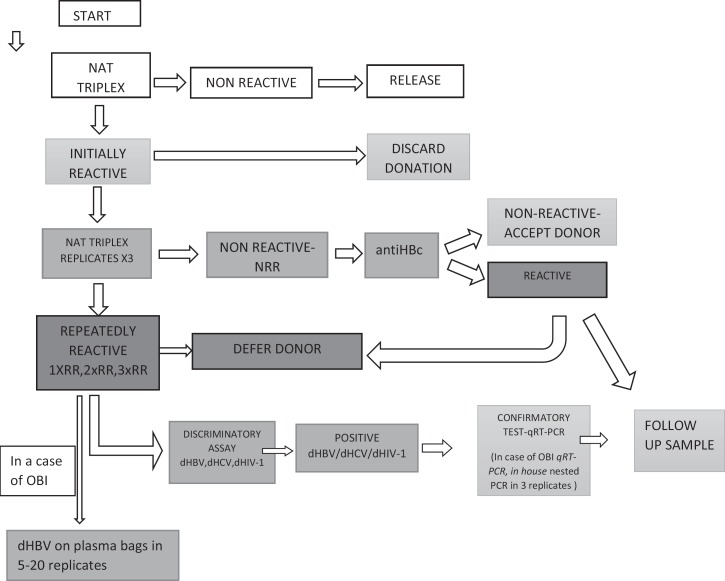

The Procleix Ultrio Plus Assay is a multiplex NAT test for simultaneous detection of HBV DNA, HCV RNA, and HIV-1 RNA. The 95% probability of detecting each of the three viruses was similar between the Procleix Ultrio Plus assay and the discriminatory assay, i.e. 21.2 versus 18.9 IU/ml, 5.4 versus 4.4 IU/ml and 3.4 versus 4.1 IU/ml for HIV-1, HCV and HBV, respectively. The algorithm of ID-NAT testing at the CITM is presented in figure 1. We decided to implement anti-HBc testing (Architect; Abbott Diagnostics, Abbott Park, IL, USA) for each initially reactive (IR) repeatedly non-reactive (NRR) donation to improve the sensitivity of OBI detection in blood donors.

Fig. 1.

NAT testing algorithm at the CITM.

The follow-up testing included routine and confirmatory NAT and serologic testing – for HBV HBsAg tests (ELISA/CMIA and, if necessary ELFA), the quantitative HBsAg and neutralization test, all HBV markers; for HCV a combination of anti-HCV and HCV Ag/Ab (ELISA/ELFA), optionally HCV Ag, imunoblot test (if needed 2); for HIV-1 a combination of 3 HIV Ag/Ab assays (ELFA/ELISA/CMIA) and anti-HIV, HIV-Ag and imunoblot test (if needed 2). Confirmatory testing and detection of viral load with an alternative NAT method was performed in the incriminating donation and in the follow-up sample with COBAS Ampliprep/COBAS TaqMan RT-PCR tests, v 2.0, for HBV, HCV, and HIV-1, with detection limits of 20 IU/ml for HBV, 15 IU/ml for HCV, and 20 cp/ml for HIV1 RNA (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA). In a case of OBI, discriminatory HBV assay was performed on plasma bags in 5–20 replicates, and ‘!’ nested PCR amplification of HBV pre-S and S gene was performed in 3 replicates. ID-NAT archive is stored at −25 °C for at least 2 years.

Residual risk for TTI based on ID-NAT was calculated according to proposed WHO guidelines [12].

Trace-Back and Look-Back Procedures

Donor-directed look-back (LB) procedures were initiated when confirmed viral infection in repeat donor was established. From our IT database we retrieved all data on the incriminating donations. In case of HBV, HCV and HIV-1 NAT and/or serology-positive units, we tested all recipients of the last negative donation. If the blood recipients deceased or were unreachable, then donors' archived samples were thawed and tested by ID-NAT for the presence of viral markers. In a case of confirmed OBI, we tested all available archived samples and then all reachable recipients of HBV-positive donations determined during LB procedure.

Results

A total of 545,463 donations were collected and tested for HBV, HCV, and HIV-1 during the 3-year period. The overall specificity was 99.95%, and the rate of invalid runs was around 2%. The results of NAT testing were delayed 31 times from optimal validation time (9.30 a.m. day 1) by not more than 10 h. Hardware failure on Tigris instruments or other problems in testing (28/31, 90%) was one of the main reasons for delay of the results. We found 322 (0.06%) ID-NAT IR samples: 214 (0.04%) were found to be false-positive, and 108 (0.02%) were ID-NAT repeatedly positive blood donations. All IR donations were discarded in order to avoid potentially low-level viremic units missed by repeat testing. There were 51 ID-NAT only positive donations (50 HBV NAT and 1 HIV-1 NAT positive blood donors). NAT yield cases were predominantly HBV NAT reactive; they were later found to be anti-HBc positive, and determined as OBI infections. WP was determined for 1 HIV-1 NAT positive donation. The highest prevalence of reactive blood donor samples was recorded in the CITM (56/108), as it the most important blood center that collects and distributes approximately 56% of total blood supply in the country. Table 1 shows the number of interdicted infectious blood units according to serology and ID-NAT testing. Among 108 RR ID-NAT donations, 16 (14.8%) blood donations were HCV-NAT and anti-HCV reactive, 9 (8.3%) donations were HIV-1 NAT and HIV Ag/At reactive, 1 donation was HIV-1 NAT only reactive (0,9%), and 82 (76%) blood donations were HBV-NAT reactive. All ID-NAT yield cases for HBV were OBIs (50/82), defined by the presence of HBV DNA in the absence of HBsAg. Viral loads in individual donations ranged from <2.00 × 101 to >1.7 × 108 IU/ml for HBV, from 3.64 × 103 to 7.89 × 106 IU/ml for HCV, and from 1.82 × 102 to 9.93 × 104 C/ml for HIV-1. In all cases of NAT positive / serology positive samples as well as in the WP HIV 1 infection, follow-up samples were also positive when tested with an alternative NAT method.

Table 1.

Number of repeatedly reactive blood units interdicted during 3 years in Croatian blood supply according to ID-NAT and serology

| Testing | Number of repeated reactive blood units |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| HBV | HCV | HIV-1 | |

| NAT and serology | 32 | 16 | 9 |

| Serology | 1 | 6 | 0 |

| ID-NAT only | 50 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 83 | 22 | 10 |

We estimated the risk of viral TTI in blood donations collected in Croatia from 2013 to 2016. Calculation of TTI residual risks included 481,389 blood donations from repeat donors along with 45 HBV-DNA, 1 HCV-RNA and 6 HIV-1 RNA positive donations from repeat donors. The established interdonation interval was 156 days. The residual risk of HBV TTI was 1: 36,900 (with adjustment for transient HBsAg), that of HIV-1 TTI 1:1,567,398, and that of HCV TTI 1:15,015,015.

OBI among Tested Donations

The prevalence of OBI was much higher among repeat donors 45/50 (90%). The majority of OBI carriers were males (43/50, 86%), which is in accordance with sex distribution of the general blood donor population, and they were generally older than the total donor population (median age 58 years). ID-NAT testing for OBI cases showed reproducibility of 59% when repeat testing in triplicate was performed. Overall, 29 donor samples had 2–3 positive replicates and 21 samples only 1 replicate positive, when tested in triplicate. This was explained by determining blood donor samples with a very low HBV-DNA titer. Only 38/50 blood donors with OBI had positive ID-NAT test in follow-up sample, and 9/50 had negative ID-NAT result, while 3 samples are still in process. There were considerable fluctuations in donor viral load over time. Only 3 donors had a measurable HBV-DNA titer (ca. 10 × 102 IU/ml) in their follow-up sample. In 20 follow-up confirmatory samples, the titer was reactive at <20 IU/ml HBV DNA, whereas in another 20 blood donors we were not able to detect HBV DNA in follow-up samples, which could be explained by extremely low (1–5 IU/ml) and fluctuating HBV DNA titers close to the method detection level. Four follow-up samples did not have enough material for HBV DNA confirmation, and 3 are still in process. Almost all blood donors with OBI were anti-HBc positive (98%) and in some cases (50%) anti-HBs and/or anti-HBe positive. The levels of anti-HBs ranged between 9 and 784 IU/l. Finally, during the 2013–2016 period, 50 HBV positive donations were discarded according to NAT only, yielding an incidence of OBI infection of 1 per 10,900 donations.

Prevention of HIV-1 Infection Transmission in the WP

One ID-NAT only positive donation given by a 54-year-old repeat donor was determined by routine ID-NAT testing and identified as a WP HIV-1 infection. HIV-1 RNA quantitative assay confirmed the presence of the virus in a load of less than 2.00 × 101 C/ml. Routine serologic screening test for HIV Ag/Ab (Abbott Prism HIV Ag/Ab Combo, Abbott Diagnostics) was negative as well as all confirmatory tests including alternative HIV Ag/Ab, anti-HIV-1/2, HIV-1 p24 Ag and anti-HIV-1/2 immunoblot assay. The follow-up blood sample obtained 6 days after the incriminating donation showed an increasing titer of HIV-1 (3.52 × 104 C/ml), but serologic screening HIV Ag/Ab test was still negative. However, the confirmatory tests, the alternative HIV Ag/Ab assay and HIV-1 p24 were weakly positive, but anti-HIV-1/2 and anti-HIV-1/2 immunoblot test were still negative. The HIV-1 NAT yield demonstrated the first case of HIV-1 RNA in the WP and thus successfully prevented possible TTI with HIV-1 to one or more recipients.

LB Procedures after Confirmed Blood Donor Infection in CITM

In a 3-year period, the CITM conducted 47 LB procedures, most of which affected HBV OBI cases (76,6%). For the OBI LB procedures, 101 samples of the serologic archive and 30 samples of the NAT archive were tested of which 34 (33.7%) and 6 (20%), respectively, were found to be HBV DNA positive. There were only 2 probable transmissions of HBV from 2 OBI donors. One recipient was tested positive for HBV DNA directly after blood transfusion; 8 months after the incriminating blood transfusion he showed serologic markers of resolved HBV infection and negative HBV DNA. The other recipient had anti-HBc and anti-HBe positive markers without HBV DNA. It is not known whether or not the recipients had these markers before the incriminating transfusion. Interpreting the LB data over 3 years, we noticed the decreasing trend in OBI cases among repeat donors, and we are expecting a further decrease due to the very sensitive tests and strict algorithm. There were no confirmed HCV or HIV-1 TTI cases in our recipients.

Discussion

In recent years, transfusion safety has undergone significant improvement, and blood transfusion therapy has never been as safe as it is nowadays. This enormous gain towards blood safety has been achieved through many factors including more stringent donor selection criteria, improved sensitivity of the screening tests, improvements in preparation and quality control of blood components, and inclusion of NAT testing in the routine screening program [13]. Recent studies performed in other countries have shown that the estimated risk of TTI via blood products is very low [14, 15, 16]. The main advantages of NAT screening are interdiction of WP infections and identification of OBI carrier status, offering blood centers a much higher sensitivity for detecting blood-borne infections [17]. Reports from developed countries showed a limited value of NAT screening in improving blood safety [17, 18]. In contrast to this, the prevalence of TTIs in resource-limited countries is always high, and these countries are likely to yield a significant number of WP donations; thus NAT testing is expected to be more cost-effective in these countries. These resource-limited settings mainly include countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America with a high prevalence of blood-borne virus infections.

NAT yields have been determined for several countries in the last decade. Italy has reported a NAT yield rate for HBV, HCV and HIV-1 of 57.8 per million, 2.5 per million and 1.8 per million, respectively [14]. Slovenia has reported similar data, with 63.3 per million for HBV, 4.27 per million for HCV and 0.0 per million for HIV-1 [19]. Compared to the neighboring countries, Croatia has reported higher NAT yields of 91.7 per million donations for HBV and 1.8 per million donations for HIV-1, whereas the HCV NAT yield was lower (0.00 per million). Yield rates observed for HIV-1 NAT are similar to those in France and Germany (0.3 per million donations). Higher rates have been reported from Greece and Spain (2–4 per million donations). For HCV, the rates of NAT are lower in northern countries (Switzerland 0.45 per million donations and Ireland 0.00 per million donations) than in Mediterranean countries (Spain 2.15 per million and Greece 5.97 per million. Countries with low HBV endemism, such as Germany, Switzerland, New Zealand, the US and Canada, reported HBV NAT yields of up to 1:730,000 [20, 21, 22, 23, 24], whereas countries with moderate endemism such as Poland and some Mediterranean countries reported figures up to 1:51,987 [25, 26, 27]. The HBV NAT incidence rate of 1 per 10,900 donations in Croatia is comparable to the HBV incidence rate of 1:15,600 HBV positive donations in Slovenia. Other neighboring countries have not yet implemented NAT screening testing of blood donors. In countries with high endemism, such as Ghana, Hong Kong, India and South Africa, the reported NAT HBV yield ranged from 1:186 to 1:5,200 [28, 29, 30, 31, 32].

Croatia has a population of 4.3 million and collects about 195,000 blood donations per year. It belongs to countries with low prevalence of HBV, HCV, and HIV-1 infections in the general population, as well as in blood donors. The introduction of mandatory hepatitis B vaccination of schoolchildren in 1999 and later of newborns in 2007 resulted in a decrease in the incidence of hepatitis B, and a further decline is expected. The incidence of hepatitis C in Croatia is decreasing as well; less than 2% of the population are anti-HCV positive. In spite of a relatively favorable epidemiological status, hepatitis B and C still pose a significant public health burden. The annual incidence of HIV-1 infections ranges from 12 per million to 19 per million in the general population. Thus, Croatia is among the countries with a low HIV-1 prevalence (the average prevalence in the EU/EEA in 2012 is 58 per million), with the two most-at-risk groups of men having sex with men and commercial sex workers [33]. However, over the last years an albeit very modest increase in the HIV-1 incidence has been detected, mostly among men in the general population as well as in the population of blood donors. Implementation of centralized NAT testing in 2013 and standardized quality of testing and production of blood components have improved blood safety by reducing the risk of transfusing infectious units to blood recipients to entering 2 per million in case of HIV-1 and to 91.67 per million in case of HBV. During the study period, we did not find any WP donation for HCV infection (0.0 per million donations). Considering all HBV DNA positive donors found in Croatia, the risk of a potentially infectious donation was much higher for HBV than for HCV or HIV. OBIs were considerably more frequently detected among older repeat blood donors. Almost all (98%) Croatian OBI donors were anti-HBc positive, and approximately half of them also carry anti-HBe and anti-HBs, with 40% of them having titers of more than 10 IU/l, potentially able to neutralize viral infectivity. Similar data are described in other publications [26, 34] suggesting that OBIs occur largely in individuals that have recovered from the infection but were unable to develop a totally effective immune control against HBV [4, 11]. The infectivity of HBV depends on many factors, e.g. viral dose (number of HBV genome copies/ml), blood component which was transfused (fresh frozen plasma and platelet concentrates suspended in plasma are considered more infectious than red cell concentrates), the presence of anti-HBs, and the recipient immune status [35]. The neutralizing capacity of low anti-HBs may be inefficient when overcome by high viral load. Satake et al. [36] reported that blood components collected from OBI donors with low levels of anti-HBc were more than 10 times less infectious than units collected from donors in the WP of infection. Although the OBI infectivity potential seems to be low, especially if anti-HBs is present, rare transmissions causing acute liver failure have been reported in immunosuppressed patients [37]. The OBIs are also characterized by very low HBV DNA plasma load, mostly below 1,000 IU/ml and often below 100–10 IU/ml. At low HBV viral load, pool testing is likely to be ineffective, and most of our OBI cases would be missed on MP-NAT testing. Even the ID-NAT testing is sometimes ineffective to detect titers below 95% limit of detection of HBV-DNA in OBIs. Only testing in replicates enables higher sensitivity as demonstrated by our archived sample analysis. According to our LB data, we found no evidence of any case of TTI confirmed from OBI donors. Only two blood recipients had markers of the resolved HBV infection but it is hard to conclude on the causal relationship since we did not have any data on their status before the transfusion and the genome sequencing was not completed. The high residual risk for HBV TTI is predominantly influenced by higher number of OBIs detected in the repeat donor population after introduction of ID-NAT. On the other hand, the extremely low residual risk for HCV TTI could be explained by the very short WP of HCV ID-NAT. During the first year of NAT implementation, the finding of OBI blood donors was relatively frequent, but with time their number decreased with deferral of occult carriers, and we are expecting a further decreasing trend. The prevalence of the other two viral markers was stable and oscillated around 0.0004 and 0.0002 for HCV and HIV-1, respectively.

Conclusion

The choice of centralized ID-NAT screening, the implementation of IT transfusion network for the whole country, and the cooperation among 8 blood centers has proved to be effective for improving blood transfusion safety without compromising optimal blood product supply and release on time. Completion of testing on time is of utmost importance for the transfusion service when considering the short shelf life of the some of the blood products. The number of HBV-infected donors interdicted during the study, along with the HIV-1 WP infection, justifies the implementation of ID-NAT testing for donor screening. There is no possibility to produce blood components with a zero risk of TTI due to the WP of infections and new emerging/reemerging threats, but NAT testing of blood donors and other measures such as vaccination against HBV are crucial for further reducing the risk of TTI towards zero. Additional improvements could be achieved by the implementation of NAT screening for HIV-2 virus in Croatia and by a more sensitive test for confirmatory testing for HBV DNA with an alternative NAT method in the follow-up samples.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all transfusion centers in Croatia for good cooperation in preparing the data for manuscript. Also we thank all technicians doing the NAT testing at the CITM for their excellent working skills.

References

- 1.World Health Assembly, 63: Viral Hepatitis – Report by the Secretariat 2010. http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/2383. (last accessed April 19, 2017).

- 2.Roth WK, Busch MP, Schuller A, et al. International survey on NAT testing of blood donations: expanding implementation and yield from 1999 to 2009. Vox Sang. 2012;102:82–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2011.01506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coste J, Reesink HW, Engelfriet CP, et al. Implementation of donor screening for infectious agents transmitted by blood by nucleic acid technology: update to 2003. Vox Sang. 2005;88:289–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2005.00636_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biswas R, Tabor E, Hsia CC, Wright DJ, Laycock ME, Fiebig EW, Peddada L, Smith R, Schreiber GB, Epstein JS, Nemo GJ, Busch MP. Comparative sensitivity of HBV NATs and HBsAg assays for detection of acute HBV infection. Transfusion. 2003;43:788–798. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2003.00424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Candotti D, Allain JP. Transfusion transmitted hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2009;51:798–809. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar R, Gupta S, Kaur A, Gupta M. Individual donor nucleic acid testing for human imunodefficiency virus-1, hepatitis C virus and hepatitis B virus and its role in blood safety. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2015;9:199–202. doi: 10.4103/0973-6247.154250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allain JP. Occult hepatitis B virus infection: implications in transfusion. Vox Sang. 2004;86:83–91. doi: 10.1111/j.0042-9007.2004.00406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chatterjee K, Coshic P, Borgohain M, Thapliyal RM, Chakroborty S, Sunder S. Individual donor nucleic acid testing for blood safety against HIV-1 and hepatitis B and C viruses in a tertiary care hospital. Natl Med J India. 2012;25:207–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seo DH, Whang DH, Song EY, Han KS. Occult hepatitis B virus infection and blood transfusion. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:600–606. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i3.600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Makroo RN, Chowdhry M, Bhatia A, Antony M. Evaluation of the Procleix Ultrio Plus ID NAT assay for detection of HIV1, HBV and HCV in blood donors. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2015;9:29–30. doi: 10.4103/0973-6247.150944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stramer SL, Wend U, Foster GA, Hollinger FB, Dodd RY, Allain JP, Gerlich W. Nucleic acid testing to detect HBV infection in blood donors. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:236–247. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization WHO Guidelines on Estimation of Residual Risk of HIV, HBV or HCV Infections via Cellular Blood Components and Plasma. October 2016. Expert Committee on Biological Standardization, Geneva, 17 to 21 October 2016. www.who.int/biologicals/expert_committee/Residual_Risk_Guidelines_final.pdf (last accessed April 19, 2017).

- 13.Laperche S. Blood safety and nucleic acid testing in Europe. Euro Surveill. 2005;10:3–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Velati C, Romano L, Formiatti L, Baruffi L, Zanetti AR, SIMTI Research Group Impact of nucleic acid testing for hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and human immunodeficiency virus on the safety of blood supply in Italy: a 6-year survey. Transfusion. 2008;48:2205–2213. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niederhauser C, Schneider P, Fopp M, Ruefer A, Levy G. Incidence of viral markers and evaluation of the estimated risk in the Swiss blood donor population from 1996 to 2003. Euro Surveil. 2005;10:518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pillonel J, Laperche S, Saura C, Desenclos JC, Couroucé AM, Transfusion-Transmissible Agents Working Group of the French Society of Blood Transfusion Trends in residual risk of transfusion-transmitted viral infections in France between 1992 and 2000. Transfusion. 2002;42:980–988. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2002.00155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El Ekiaby M, Lelie N, Allain JP. Nucleic acid testing (NAT) in high prevalence-low resource settings. Biologicals. 2010;38:59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chigurupati P, Murthy KS. Automated nucleic acid amplification testing in blood banks: an additional layer of blood safety. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2015;9:9–11. doi: 10.4103/0973-6247.150938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levicnik Stezinar S, Nograsek P. Yield of NAT screening in Slovenia. Zdrav Vestn. 2012;81:257–264. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Niederhauser C. Reducing the risk of hepatitis B virus transfusion-transmitted infection. J Blood Med. 2011;2:91–102. doi: 10.2147/JBM.S12899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roth WK, Seifried E. The German experience with NAT. Transfus Med. 2002;12:255–258. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3148.2002.00383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flanagan P, Charlewood G, Horder S, Drawitsky M, Hollis H. Reducing the risk of transfusion transmitted hepatitis B in New Zealand. Vox Sang. 2005;89:23–24. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stolz M, Tinguely C, Graziani M, Fontana S, Gowland P, Buser A, Michel M, Canellini G, Züger M, Schumacher P, Lelie N, Niederhauser C. Efficacy of individual nucleic acid amplification testing in reducing the risk of transfusion-transmitted hepatitis B virus infection in Switzerland, a low endemic region. Transfusion. 2010;50:2695–2706. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.02732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kleinman SH, Strong DM, Tegtmeier GG, Holland PV, Gorlin JB, Cousins C, Chiacchierini RP, Pietrelli LA. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA screening of blood donations in minipools with the COBAS AmpliScreen HBV test. Transfusion. 2005;45:1247–1257. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2005.00198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brojer E, Grabarczyk P, Liszewski G, Mikulska M, Allain JP, Letowska M, Polish Blood Transfusion Service Viral Study Group Characterization of HBV DNA+/HBsAg- blood donors in Poland identified by triplex NAT. Hepatology. 2006;44:1666–1674. doi: 10.1002/hep.21413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manzini P, Girotto M, Borsotti R, Giachino O, Guaschino R, Lanteri M, Testa D, Ghiazza P, Vacchini M, Danielle F, Pizzi A, Valpreda C, Castagno F, Curti F, Magistroni P, Abate ML, Smedile A, Rizzetto M. Italian blood donors with anti-HBc and occult hepatitis B virus infection. Haematologica. 2007;92:1664–1670. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katsoulidou A, Moschidis Z, Sypsa V, Chini M, Papatheodoridis GV, Tassopoulos NC, Mimidis K, Karafoulidou A, Hatzakis A. Analytical and clinical sensitivity of the Procleix Ultrio HIV-1/HCV/HBV assay in samples with a low viral load. Vox Sang. 2007;92:8–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2006.00857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nantachit N, Thaikruea L, Thongsawat S, Leetrakool N, Fongsatikul L, Sompan P, Fong YL, Nichols D, Ziermann R, Ness P, Nelson KE. Evaluation of a multiplex human immunodeficiency virus-1, hepatitis C virus, and hepatitis B virus nucleic acid testing assay to detect viremic blood donors in northern Thailand. Transfusion. 2007;47:1803–1808. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vermeulen M, Lelie N, Sykes W, Crokkes R, Swanevelder J, Gaggia L, Le Roux M, Kuun E, Gulube S, Reddy R. Impact of individual-donation nucleic acid testing on risk of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus transmission by blood transfusion in South Africa. Transfusion. 2009;49:1115–1125. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Owusu-Ofori S, Temple J, Sakrodie F, Anokwa M, Candotti D, Allain JP. Predonation screening of blood donors with rapid tests: implementation and efficacy of a novel approach to blood safety in resource-poor settings. Transfusion. 2005;45:133–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2004.04279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wong I, Lam S, Teo D. Overview of nucleic acid testing (NAT) on blood donations in Singapore. Vox Sang. 2005;89:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Makroo RN, Choudhury N, Jagannathan L, Parihar-Malhotra M, Raina V, Chaudhary RK, Marwaha N, Bhatia NK, Ganguly AK. Multicenter evaluation of individual donor nucleic acid testing (NAT) for simultaneous detection of human immunodeficiency virus-1 and hepatitis B and C viruses in Indian blood donors. Indian J Med Res. 2008;17:140–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaic T, Vilibic-Cavlek S, Kurecic Filipovic S, Nemeth-Blazic T, Pem-Novosel I, Vucina VV, Simunovic A, Zajec M, Radic I, Pavlic J, Glamocanin M, Gjenero-Margan I. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis (in Croatian) Acta Med Croatica. 2013;67:273–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katsoulidou A, Paraskevis D, Magiorkinis E, Moschidis Z, Haida C, Hatzitheodorou E, Varaklioti A, Karafoulidou A, Hatzitaki M, Kavallierou L, Mouzaki A, Andrioti E, Veneti C, Kaperoni A, Zervou E, Politis C, Hatzakis A. Molecular characterization of occult hepatitis B cases in Greek blood donors. J Med Virol. 2009;81:815–825. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Allain JP, Mihaljevic I, Gonzalez-Fraile MI, Gubbe K, Holm-Harritshoj L, Garcia JM, Brojer E, Erikstrup C, Saniewski M, Wernish L, Bianco L, Ullum H, Candotti D, Lelie N, Gerlich WH, Chudy M. Infectivity of blood products from donors with occult hepatitis B virus infection. Transfusion. 2013;53:1405–1415. doi: 10.1111/trf.12096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Satake M, Taira R, Yugi H, Hino S, Kanemitsu K, Ikeda H, Tadokoro K. Infectivity of blood components with low hepatitis B virus DNA levels identified in a lookback program. Transfusion. 2007;47:1197–1205. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gerlich WH, Wagner FF, Chudy M, Harrishoj LH, Lattermenn A, Wienzek S, Glebe D, Saniewski M, Schüttler CG, Wend UC, Willems WR, Bauerfeind U, Jork C, Bein G, Platz P, Ullum H, Dickmeiss E. HBsAg non-reactive HBV infection in blood donors: transmission and pathogenicity. J Med Virol. 2007;79:32–36. [Google Scholar]