Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this study was to determine the clinical outcomes and predictors of satisfaction in patients with lithium disilicate (LD) ceramic crowns.

Subjects and Methods

Clinical outcomes were assessed in 47 patients with 88 LD crowns using modified United States Public Health Service (USPHS) evaluation criteria and survival rates. The questionnaire for predictors included 3 aspects: (a) sociodemographic characteristics, (b) oral health habits (tooth brushing frequency, flossing frequency, and dental visits), and (c) satisfaction of the restorations (aesthetics, function, fit, cleansability, and chewing ability of the crowns, and overall satisfaction). Frequency distributions were computed using univariate and multivariate analysis. The Student t test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to compare means across variables. Correlation analysis was done to assess the association between continuous variables.

Results

The age of crowns was 34.7 ± 9.7 months. The survival rate was 96.6% at 35.9 ± 9.2 months. There was a significant association between successful crown function and oral hygiene measures: tooth brushing (p˂ 0.001), dental visits (p = 0.006), and flossing (p = 0.009). A strong negative correlation was observed between aesthetic satisfaction (r = −0.717, p˂ 0.001) and chewing ability (r = −0.639, p˂ 0.001) with crown age. The linear regression model was significant for all predictors (p < 0.05) except overall satisfaction (p > 0.05).

Conclusion

The LD crowns had long survival rates of 96.6% up to 35.9 ± 9.2 months and provided satisfactory clinical performance (low risk of failure). Oral hygiene habits such as brushing, flossing, and regular dental visits influenced patient satisfaction with LD crowns.

Keywords: Clinical outcome, Crowns, Failure, Lithium disilicate, Predictors, Survival

Significance of the Study

• In this study, lithium disilicate (LD) crowns had a long survival rate at 3 years and provided good aesthetic replacement for the lost tooth structure. Clinical oral hygiene habits including brushing, flossing, and regular dental visits were predictors of the clinical survival of LD crowns.

Introduction

Lithium disilicate (LD) ceramics have revolutionized all-ceramic restorations by enhancing the mechanical and aesthetic properties of glass-based ceramics in dentistry [1]. LD ceramics consist of a glassy matrix of silica through which lithium oxide crystals are dispersed. The crystals are oriented in an interlocking manner that inhibits the propagation of cracks and provides flexural strengths of up to 440 MPa [2]. In addition, LD ceramics can be bonded adhesively to the tooth structure through surface treatments (hydrofluoric acid) and chemical interactions (silanes), thereby allowing them to be used as conservative aesthetic restorations with improved mechanical strength [3]. The LD restorations are chemically stable and show excellent compatibility with surrounding periodontal tissues [4]. In addition, due to their excellent optical properties, LD-based aesthetic rehabilitations also enhance [5] the patient's self-esteem.

LD crowns are widely used to restore anterior teeth due to their excellent aesthetic properties [6]. Nevertheless, the survival rate depends on a number of factors such as marginal adaptation, anatomic form, and retention [7]. In a study by Yu et al. [8], the cumulative failure rate of LD crowns was 3.3% involving ceramic chipping and fracture. Fracture of the core ceramic has also been reported [9] as an important reason of failure.

The clinical success of management with LD restorations is related to the quality of the prosthodontic work, aesthetic colour matching, restorative fit, functional ability of restorations, cleansability of the crowns, and maintenance of oral hygiene [10, 11]. The most common oral diseases such as dental caries and periodontal disease are considered to be behavioural diseases, as healthy oral habits are critical for controlling oral infections [11]. Traditionally, good oral health practice consists of self-care habits such as dental hygiene, restriction of sugar intake, use of fluoride products, and utilization of dental services like oral health education and professionally applied preventive measures [12]. Maintenance of optimum oral hygiene ensures good health of soft and hard tissues associated with restorations, in turn improving their clinical success and prognosis [9].

An important aspect of clinical success in patients receiving LD restorations is patient satisfaction. Assessment of satisfaction outcomes allows for a direct appraisal of patients' opinions and feelings towards different aspects of the prosthodontic rehabilitation. Patient satisfaction with LD ceramic treatments is effected by the improvement in their oral health and aspects of their quality of life (such as function, comfort, and aesthetics) [13]. Previous studies [13, 14] have assessed and reported patient satisfaction for all-ceramic restorations with respect to oral hygiene and satisfaction of treatment. However, there are no studies reporting predictors of patient satisfaction with LD ceramic restorations and their clinical outcomes in a Malaysian population. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the clinical performance of LD single crowns and to determine the predictors of satisfaction in patients restored with LD all-ceramic crowns among a Malaysian population.

Subjects and Methods

Ethical Guideline

The study protocol was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Dentistry, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. This cross-sectional survey was conducted from January to June 2016, among patients who had been provided with LD-based core, IPS e.max Press crowns at the Postgraduate Clinic, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Malaya.

Sample Size and Inclusion Criteria

The sample size was calculated through calibration data obtained from 6 patients with 11 crowns before the commencement of the study. The sample size calculation showed that 26, 31, 41, and 94 pairs of subjects were needed to reject the null hypothesis of dental plaque, pocket depth, gingival recession, and bleeding, respectively, with 80% power. The alpha level was set at 0.05.

The inclusion criterion was LD ceramic (IPS e.max Press) crowns from graduate students in medically fit patients. Exclusion criteria were crowns made from other material, severe periodontal disease, parafunctional habits, and temporomandibular joint disorders.

Interview Questionnaire

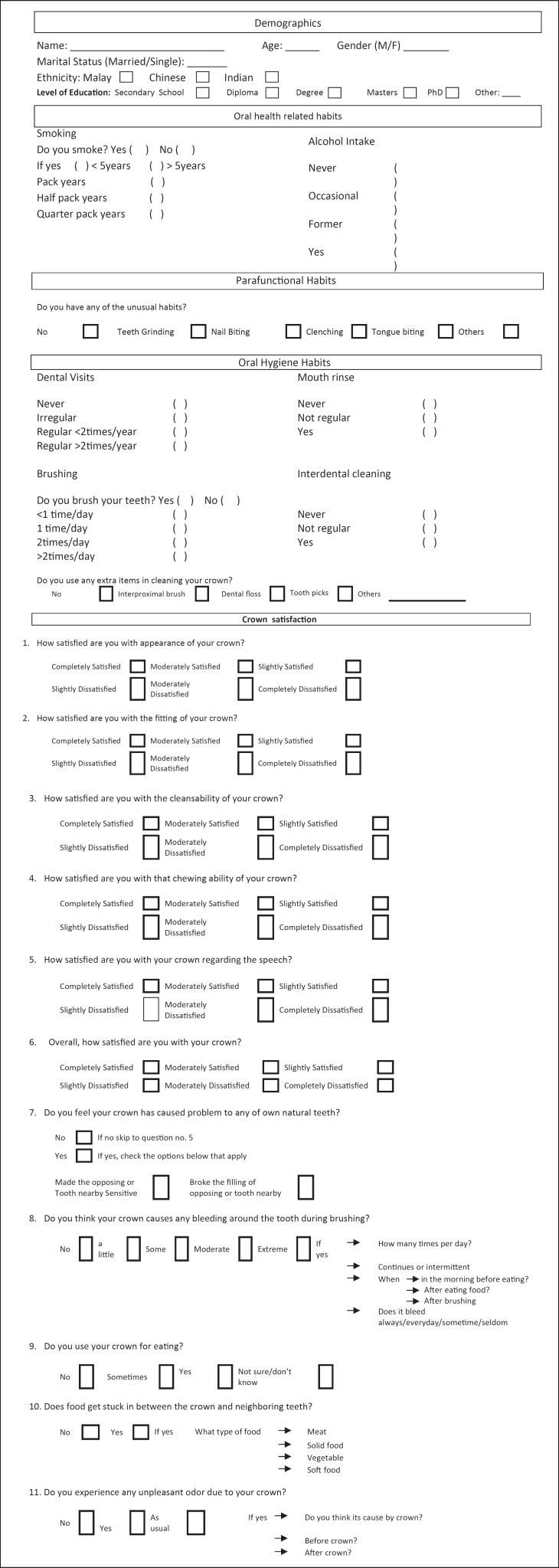

Forty-seven patients completed the questionnaire (Appendix A) [15]. The questionnaire assessed sociodemographic characteristics, oral health habits, characteristics of the restorations, and overall satisfaction. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

Prosthodontic Parameters

A single calibrated examiner (M.S.S.) examined the crowns. Intra-examiner calibration was done using the modified United States Public Health Service (USPHS) evaluation criteria (Table 1) [16]. The kappa value of all the parameters that had been examined on the participants was greater than 0.8 (0.89). All the crowns were evaluated for biological and technical complications. Pulpal and periapical conditions were clinically examined and investigated using digital periapical radiographs. Retention and fit of the crowns were detected by the rating criteria (fit: 0, unfit/mobile: 1). Crown colour match was determined using the VITAPAN classical shade guide.

Table 1.

Modified USPHS criteria used for evaluation of LD crowns

| Parameters | Rating | Restoration condition |

|---|---|---|

| Anatomic form | Alpha | The restoration is continuous with the anatomy of the teeth |

| Bravo | Slightly over- or undercontoured restoration; slightly undercontoured; contact slightly open (maybe self-correcting); locally reduced occlusal height | |

| Charlie | * Restoration is grossly over- or undercontoured, with an exposed base or dentin; faulty contact, i.e., not self-correcting; reduced occlusal height; occlusion affected | |

| Delta | * Marginal overhang present; traumatic occlusion; damaged tooth, supporting bone or soft tissues | |

| Marginal adaptation | Alpha | The restoration is continuous with current anatomic form, and the sharp explorer will not catch |

| Bravo | The sharp explorer does catch, but there are no observable crevices that the explorer will penetrate | |

| Charlie | There is a crevice at the margin, and there is an exposed enamel margin | |

| Delta | * The crevice at the margin is very apparent, and there is exposed dentine or lute | |

| Integrity of restoration | Alpha | Intact |

| Bravo | * Crack apparent on transillumination | |

| Charlie | * Fracture observable | |

| Delta | * Crown lost (state at which interface debond occurred) | |

| Colour match | Alpha | Excellent colour match and shade between restoration and adjacent tooth, restoration almost invisible |

| Bravo | Slightly mismatching between the restoration and the adjacent tooth, which is in the normal range of tooth colour, translucence, and/or shade | |

| Charlie | * Obvious mismatch, beyond the normal range | |

| Delta | * Gross mismatch/aesthetically displeasing colour, shade, and/or translucence | |

| Secondary caries | Alpha | No apparent caries contiguous with the restoration margin |

| Bravo | * Caries are observable contiguous with the restoration margin | |

| Postoperative sensitivity | Alpha | No sensitivity |

| Bravo | * Sensitivity | |

| Retention | Alpha | Complete retention of the restoration |

| Bravo | * Mobility present | |

Alpha, Bravo, Charlie and Delta implied increased severity of each nominal scale. USPHS, United States Public Health Service; LD, lithium disilicate.

Unsatisfactory.

Participants

Forty-seven patients (31 females and 16 males) with 88 LD crowns (79 anterior and 9 posterior) were included in the study. The age of the participants ranged from 18 to 64 years.

A total of 88 teeth were crowned due to the following clinical indications: aesthetic inadequacy (n = 24), tooth crown fracture (n = 19), secondary caries (n = 17), defective restoration (n = 9), primary caries/pain (n = 9), crown replacement (n = 6), and diastema (n = 4). These crowns had been cemented with self-adhesive resin cement (RelyX™ U200). In addition, among all (n = 88) crowned teeth, 19 were vital and 69 were non-vital. Sixty-eight non-vital teeth were restored with prefabricated fibre posts (RelyX™, 3M ESPE) and composite cores (Filtek™ Z350 XT, 3M ESPE), and 1 tooth was restored with glass ionomer cement core (Fuji IX, GC, Tokyo Japan). Overall patient characteristics are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Sample characteristics

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 16 (34) |

| Female | 31 (66) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Malay | 22 (46.8) |

| Chinese | 20 (42.6) |

| Indian | 5 (10.6) |

| Level of education | |

| Secondary school | 14 (29.8) |

| Diploma | 18 (38.3) |

| Degree | 13 (27.7) |

| Masters | 2 (4.3) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 20 (42.6) |

| Married | 27 (57.4) |

| Age of patients | |

| <36 years | 24 (51.1) |

| >36 years | 23 (48.9) |

| Smoking | |

| Smoker | 2 (4.3) |

| Non-smoker | 44 (93.6) |

| Occasionally | 1 (2.1) |

| Alcohol intake | |

| Yes | 1 (2.1) |

| Not regular | 5 (10.6) |

| Former | 1 (2.1) |

| Never | 40 (85.1) |

| Tooth brushing frequency | |

| Once daily | 13 (27.7) |

| >Once daily | 34 (72.3) |

| Dental visit | |

| Regular | 31 (66) |

| Irregular | 16 (34) |

| Flossing | |

| Yes | 39 (83) |

| No | 8 (17) |

Statistical Analysis

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was performed. Differences between crowns and controls were estimated using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The Student t test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to compare means across variables. Correlation analysis was used to assess the association between continuous variables. A multiple linear regression model was used for multivariate analysis.

Results

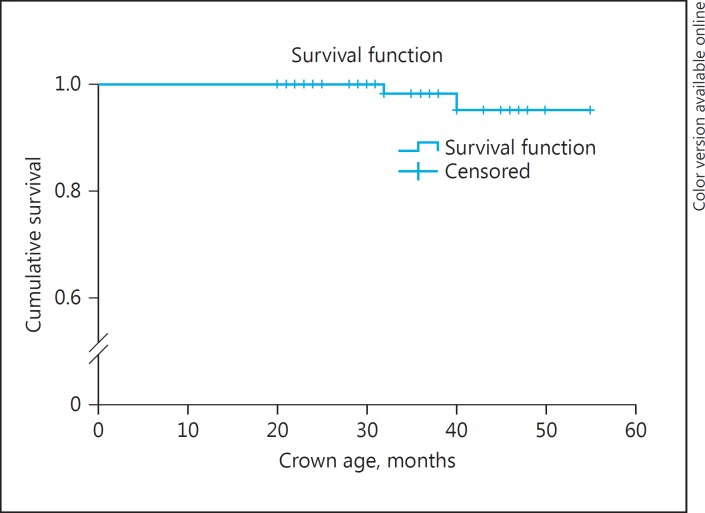

Of the 88 LD crowns assessed, the survival rate was 96.6% (n = 85) after a mean evaluation period of 35.9 ± 9.2 months. Fractures (failures) were recorded in 2 (2.2%) crowns (major chipping) on the palatal surface of a non-vital maxillary incisor 32 months after insertion and on the occlusal surface of a non-vital maxillary second premolar, which occurred 40 months after insertion. One crown (1.13%) exhibited minor chipping on the incisal edge of a root-treated maxillary central incisor. Of the 88 crowns, 20 (22.7%) and 13 (14.8%) exhibited explorer catches with no caries on the labial and palatal margins, respectively; 16 (18.2%), 12 (13.6%), and 3 (3.4%) crowns exhibited minor colour mismatch, slight over-contour and minor fractures, respectively. One (1.1%) of the fractured crowns exhibited a delta rating: “obvious crevice at margin, dentine exposed.” Postoperative sensitivity, retention, and secondary caries exhibited a 100% alpha rating in this group of subjects (Table 3). The clinical survival rate was 100% at 24 months (Fig. 1). The location of the crown had no significant effect on the crown survival rates (p = 0.17) (log-rank test).

Table 3.

Modified USPHS rating of LD crowns

| Rating |

n (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha | Bravo | Charlie | Delta | |

| Anatomic form | 76 (86.4) | 12 (13.6) | − | − |

| Marginal adaptation (labial/palatal) | 68 (77.3)/74 (84.1) | 20 (22.7)/13 (14.8) | −/− | −/1 (1.1) |

| Colour match | 72 (81.8) | 16 (18.2) | − | |

| Integrity of restoration | 85 (96.6) | − | 3 (3.4) | |

| Secondary caries | 88 (100) | − | − | |

| Postoperative sensitivity | 88 (100) | − | − | |

| Retention | 88 (100) | − | − | |

USPHS, United States Public Health Service; LD, lithium disilicate.

Fig. 1.

Survival rate of IPS e.max Press crowns (n = 88) at 3 years.

The mean age of crowns was 34.7 ± 9.7 months. Significant associations between success variables and sample characteristics are shown in Table 4. There was a significant association between chewing ability satisfaction and tooth brushing frequency (p˂ 0.001), dental visit regularity (p = 0.006) and flossing (p = 0.009). A strong negative correlation was observed between aesthetic satisfaction and age of crowns (r = −0.717, p˂ 0.001).

Table 4.

Association between crown aesthetics, chewing ability, fit, and cleansability and sample characteristics

| Variable | Aesthetics |

Chewing ability |

Fit |

Cleansability |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean ± SD | p value | mean ± SD | p value | mean ± SD | p value | mean ± SD | p value | |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 4.50 ± 2.09 | 0.697 | 4.87 ± 1.85 | 0.582 | 6.00 ± 0.00 | 0.083 | 5.93 ± 0.25 | 0.681 |

| Female | 4.74 ± 1.78 | 4.54 ± 1.99 | 5.90 ± 0.30 | 5.90 ± 0.30 | ||||

| Ethnicity | ||||||||

| Malay | 4.95 ± 1.58 | 0.611 | 5.00 ± 1.66 | 0.299 | 6.00 ± 0.00 | 5.00 ± 1.66 | ||

| Chinese | 4.40 ± 2.21 | 4.15 ± 2.20 | 5.90 ± 0.30 | 0.183 | 4.15 ± 2.20 | 0.299 | ||

| Indian | 4.40 ± 1.81 | 5.20 ± 1.78 | 5.80 ± 0.44 | 5.20 ± 1.78 | ||||

| Level of education | 0.061 | 0.015 | ||||||

| Secondary school | 4.78 ± 1.88 | 4.78 ± 2.04 | 5.85 ± 0.36 | 5.92 ± 0.07 | 0.419 | |||

| Diploma | 4.27 ± 1.96 | 4.38 ± 1.88 | 5.94 ± 0.23 | 0.497 | 5.83 ± 0.38 | |||

| Degree | 5.46 ± 1.39 | 5.46 ± 1.33 | 6.00 ± 0.00 | 6.00 ± 0.00 | ||||

| Masters | 2.00 ± 1.41 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 6.00 ± 0.00 | 6.00 ± 0.00 | ||||

| Marital status | 0.901 | |||||||

| Single | 4.70 ± 1.92 | 4.60 ± 2.01 | 0.859 | 6.00 ± 0.00 | 0.083 | 6.00 ± 0.00 | 0.043 | |

| Married | 4.62 ± 1.88 | 4.70 ± 1.91 | 5.88 ± 0.32 | 5.85 ± 0.36 | ||||

| Age of patients | 0.429 | |||||||

| <36 years | 4.87 ± 1.80 | 4.83 ± 1.90 | 0.536 | 6.00 ± 0.00 | 0.083 | 6.00 ± 0.00 | 0.043 | |

| >36 years | 4.43 ± 1.97 | 4.47 ± 1.99 | 5.86 ± 0.34 | 5.82 ± 0.38 | ||||

| Smoking | ||||||||

| Smoker | 6.00 ± 0.00 | 0.452 | 6.00 ± 0.00 | 0.474 | 6.00 ± 0.00 | 6.00 ± 0.00 | ||

| Non-smoker | 4.56 ± 1.90 | 4.56 ± 1.96 | 5.93 ± 0.25 | 0.903 | 5.90 ± 0.29 | 0.869 | ||

| Occasionally | 6.00 ± 0.00 | 6.00 ± 0.00 | 6.00 ± 0.00 | 6.00 ± 0.00 | ||||

| Alcohol intake | 0.665 | 0.488 | ||||||

| Yes | 6.00 ± 0.00 | 6.00 ± 0.00 | 6.00 ± 0.00 | 5.00 ± 0.00 | ||||

| Not regular | 3.80 ± 2.58 | 4.40 ± 2.30 | 6.00 ± 0.00 | 0.914 | 6.00 ± 0.00 | 0.007 | ||

| Former | 5.00 ± 0.00 | 2.00 ± 0.00 | 6.00 ± 0.00 | 6.00 ± 0.00 | ||||

| Never | 4.72 ± 1.82 | 4.72 ± 1.90 | 5.92 ± 0.26 | 5.92 ± 0.26 | ||||

| Tooth brushing frequency | ||||||||

| 1 time/day | 2.61 ± 1.98 | <0.001 | 2.15 ± 0.89 | 6.00 ± 0.00 | 0.083 | 5.92 ± 0.27 | 0.903 | |

| >1 time/day | 5.44 ± 1.10 | 5.61 ± 1.23 | <0.001 | 5.91 ± 0.28 | 5.91 ± 0.28 | |||

| Dental visit regularity | ||||||||

| Regular | 5.45 ± 1.36 | <0.001 | 5.25 ± 1.59 | 0.006 | 6.00 ± 0.00 | 0.083 | 5.93 ± 0.24 | 0.537 |

| Irregular | 3.12 ± 1.82 | 3.50 ± 2.06 | 5.81 ± 0.40 | 5.87 ± 0.34 | ||||

| Flossing frequency | ||||||||

| Use | 5.02 ± 1.73 | 0.005 | 5.02 ± 1.78 | 5.97 ± 0.16 | 0.216 | 5.97 ± 0.16 | 0.099 | |

| Don't use | 2.87 ± 1.55 | 2.87 ± 1.72 | 0.009 | 5.75 ± 0.46 | 5.62 ± 0.51 | |||

| Age of crown | r = −0.717 | <0.001 | r = −0.639 | <0.001 | r = 1.139 | 0.194 | r = 1.645 | 0.314 |

In multivariate analysis, for cleansability satisfaction, the significant predictor was flossing frequency (p = 0.006). For all 6 satisfaction domains, the significant predictors were tooth brushing frequency (p < 0.001), dental visit regularity (p = 0.021), and age of crowns (p = 0.006). There was no multi-collinearity between the variables (Table 5). In multivariate analysis, there were no significant predictors for overall satisfaction, and the total model was also not significant (p = 0.403).

Table 5.

Predictors of appearance, chewing ability, fit, cleansability, overall satisfaction, and 6 domains of satisfaction with the crowns in multivariate analysis

| Variables | B | SE | β | p value | 95% CI for B |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| range | ||||||

| Appearance | ||||||

| Tooth brushing frequency | 1.803 | 0.397 | 0.434 | 0.000 | 1.001 | 2.604 |

| Dental visit regularity | 1.154 | 0.388 | 0.294 | 0.005 | 0.370 | 1.937 |

| Flossing frequency | 0.088 | 0.495 | 0.018 | 0.860 | −0.910 | 1.086 |

| Age of crowns | −0.72 | 0.027 | −0.331 | 0.010 | −0.126 | −0.018 |

| Chewing ability | ||||||

| Tooth brushing frequency | 2.791 | 0.389 | 0.652 | 0.000 | 2.007 | 3.576 |

| Dental visit regularity | 0.543 | 0.380 | 0.134 | 0.161 | −0.224 | 1.309 |

| Flossing frequency | 0.153 | 0.484 | 0.030 | 0.753 | −0.823 | 1.130 |

| Age of crowns | −0.051 | 0.026 | −0.026 | 0.040 | −0.002 | −0.103 |

| Fitting | ||||||

| Tooth brushing frequency | −0.247 | 0.079 | −0.452 | 0.003 | −0.406 | −0.088 |

| Dental visit regularity | 0.140 | 0.077 | 0.272 | 0.075 | −0.015 | 0.296 |

| Flossing frequency | 0.197 | 0.098 | 0.303 | 0.051 | 0.000 | 0.395 |

| Age of crowns | −0.007 | 0.005 | −0.229 | 0.220 | −0.017 | 0.004 |

| Cleansability | ||||||

| Toothbrushing frequency | −0.173 | 0.094 | −0.277 | 0.074 | −0.363 | 0.017 |

| Dental visit regularity | −0.048 | 0.092 | −0.082 | 0.603 | −0.234 | 0.137 |

| Flossing frequency | 0.339 | 0.117 | 0.457 | 0.006 | 0.103 | 0.576 |

| Age of crowns | −0.008 | 0.006 | −0.240 | 0.220 | −0.021 | 0.005 |

| Overall | ||||||

| Tooth brushing frequency | −0.200 | 0.207 | −0.165 | 0.339 | −0.618 | 0.218 |

| Dental visit regularity | −0.100 | 0.202 | −0.087 | 0.623 | −0.509 | 0.308 |

| Flossing frequency | 0.446 | 0.258 | 0.309 | 0.091 | −0.074 | 0.966 |

| Age of crowns | −0.001 | 0.014 | −0.023 | 0.916 | −0.029 | 0.027 |

| Six domains | ||||||

| Toothbrushing frequency | 3.974 | 0.721 | 0.477 | 0.000 | 2.518 | 5.430 |

| Dental visit regularity | 1.688 | 0.705 | 0.214 | 0.021 | 0.265 | 3.111 |

| Flossing frequency | 1.224 | 0.898 | 0.123 | 0.180 | −0.589 | 3.037 |

| Age of crowns | −0.139 | 0.048 | −0.317 | 0.006 | −0.236 | −0.041 |

B, regression estimate; SE, standard error; β, regression coefficient.

Discussion

In this study the LD crowns showed overall satisfactory clinical performance (low risk of failure). In addition, oral hygiene habits showed significant influence on patient satisfaction with LD crowns.

The survival rate of 96.6% at 35.9 ± 9.2 months in the present study was similar to those reported in previous studies (95.4 and 97.8%) [17, 18]. A possible explanation for the high survival rates in the present study was the location of crowns, as 89.7% of all LD crowns were on anterior teeth. A high failure rate of up to 8.2% for posterior LD single crowns, in comparison to 3.2% for anterior teeth, has been reported [19]. In the present study, 2 crowns showed major chipping and 1 crown showed minor chipping. The major chipping observed in non-vital teeth at 32 and 40 months, respectively, could be due to lack of proprioception [20]. Only 1 crown exhibited minor chipping on the incisal edge of a root-treated maxillary central incisor. Major and minor chipping is the most common form of failure in layered LD restorations. In a study by Yang et al. [19], 41.2% of failures among LD restorations was due to veneer ceramic chipping. In the present study all crowns were layered, therefore the fabrication technique of LD ceramics (layered) could possibly have caused the failures observed in the study. As a consequence, monolithic LD ceramic restorations are increasingly investigated for their mechanical properties and are introduced clinically to avoid veneer fracture, hence improving clinical outcomes [21].

In the present study, patients were satisfied with the aesthetics and functional performance of the LD restorations provided. In addition, a self-adhesive resin luting cement designed to be light-cured was employed, making the cement more colour stable. It has been reported that although all-ceramic restorations reproduce highly aesthetic outcomes [22, 23], it depends on an adequate application of techniques and selection of cement type [24, 25]. Moreover, patient satisfaction with LD crown treatment was also found to be associated with level of education and age of crowns along with oral hygiene predictors. The aesthetic and functional satisfaction findings of the present research are in agreement with previous findings [26, 27].

This was a retrospective study, and therefore it limited the ability of the investigators in controlling clinical techniques, which vary among different operators. In addition, postgraduate students, and not experts, operated on all the included patients, possibly influencing the clinical outcomes of the LD crowns. In addition, the subject numbers at recall visits were low. However, low response rates do not necessarily compromise the results of population surveys unless systematic differences between participants and non-participants are observed [28]. An important finding was the excellent aesthetics outcome with the use of light-cured resin cement and layered LD restorations. In addition, oral health habits were significantly associated with aesthetic satisfaction. In a general perspective, the tradition of regular self-care practices in the Malaysian community was high; around two-thirds of the respondents brushed their teeth more than once a day and another one-third claimed tooth brushing less than once a day. In contrast with studies carried out in Scandinavia [29] and Latvia [30], oral hygiene habits of Malaysian people were not influenced by gender and level of education. It is worth noting that self-care practices in relation to aesthetic appearance and functional satisfaction in oral health tend to be more frequent in dental attenders than non-attenders. This study recommends that dentists should educate patients on oral hygiene habits associated with treatment success with LD crowns. Furthermore, clinical outcomes of monolithic LD restorations should be assessed by undergoing randomized controlled trials.

Conclusion

The LD crowns provided satisfactory clinical performance (low risk of fracture) and had a survival rate of 96.6% for a follow-up period of up to 55 months. Moreover, oral health habits such as brushing, flossing, and regular dental visits influenced patient satisfaction with LD crowns.

Acknowledgement

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University for funding this work through the research group (RGP-1438-024). The authors also appreciate the work of the technical laboratory staff at the Faculty of Dentistry, University of Malaya.

Appendix A

Patient satisfaction questionnaire sheet.

References

- 1.Ritter RG. Multifunctional uses of a novel ceramic-lithium disilicate. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2010;22:332–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8240.2010.00362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rizkalla AS, Jones DW. Mechanical properties of commercial high strength ceramic core materials. Dent Mater. 2004;20:207–212. doi: 10.1016/s0109-5641(03)00093-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zogheib LV, Bona AD, Kimpara ET, et al. Effect of hydrofluoric acid etching duration on the roughness and flexural strength of a lithium disilicate-based glass ceramic. Braz Dent J. 2011;22:45–50. doi: 10.1590/s0103-64402011000100008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kimmich M, Stappert CF. Intraoral treatment of veneering porcelain chipping of fixed dental restorations: a review and clinical application. J Am Dent Assoc. 2013;144:31–44. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2013.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis L, Ashworth P, Spriggs L. Psychological effects of aesthetic dental treatment. J Dent. 1998;26:547–554. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(97)00031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Culp L, McLaren EA. Lithium disilicate: the restorative material of multiple options. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2010;31:716–725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Etman MK, Woolford MJ. Three-year clinical evaluation of two ceramic crown systems: a preliminary study. J Prosthet Dent. 2010;103:80–90. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(10)60010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu J, Yang Y, Gao J, et al. Clinical outcomes of different types of tooth-supported bilayer lithium disilicate all-ceramic restorations after functioning up to 5 years: a retrospective study. J Dent. 2016;51:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2016.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valenti M, Valenti A. Retrospective survival analysis of 261 lithium disilicate crowns in a private general practice. Quintessence Int. 2009;40:573–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bos A, Hoogstraten J, Prahl-Andersen B. Expectations of treatment and satisfaction with dentofacial appearance in orthodontic patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2003;123:127–132. doi: 10.1067/mod.2003.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donovan TE. Factors essential for successful all-ceramic restorations. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139:S14–S18. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Addy M, Dummer PM, Hunter ML, et al. The effect of toothbrushing frequency, toothbrushing hand, sex and social class on the incidence of plaque, gingivitis and pocketing in adolescents: a longitudinal cohort study. Community Dent Health. 1990;7:237–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fabbri G, Zarone F, Dellificorelli G, et al. Clinical evaluation of 860 anterior and posterior lithium disilicate restorations: retrospective study with a mean follow-up of 3 years and a maximum observational period of 6 years. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2014;34:164–177. doi: 10.11607/prd.1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haselton DR, Diaz-Arnold AM, Hillis SL. Clinical assessment of high-strength all-ceramic crowns. J Prosthet Dent. 2000;83:396–401. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3913(00)70033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frank RP, Milgrom P, Leroux BG, et al. Treatment outcomes with mandibular removable partial dentures: a population-based study of patient satisfaction. J Prosthet Dent. 1998;80:36–45. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3913(98)70089-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bayne SC, Schmalz G. Reprinting the classic article on USPHS evaluation methods for measuring the clinical research performance of restorative materials. Clin Oral Investig. 2005;9:209–214. doi: 10.1007/s00784-005-0017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pjetursson BE, Sailer I, Zwahlen M, et al. A systematic review of the survival and complication rates of all-ceramic and metal-ceramic reconstructions after an observation period of at least 3 years. Part I. Single crowns. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2007;3:73–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2007.01467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pieger S, Salman A, Bidra AS. Clinical outcomes of lithium disilicate single crowns and partial fixed dental prostheses: a systematic review. J Prosthet Dent. 2014;112:22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang Y, Yu J, Gao J, et al. Clinical outcomes of different types of tooth-supported bilayer lithium disilicate all-ceramic restorations after functioning up to 5 years: a retrospective study. J Dent. 2016;51:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2016.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McLean A. Criteria for the predictably restorable endodontically treated tooth. J Can Dent Assoc. 1998;64:652–656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guess PC, Zavanelli RA, Silva NR, et al. Monolithic CAD/CAM lithium disilicate versus veneered Y-TZP crowns: comparison of failure modes and reliability after fatigue. Int J Prosthodont. 2010;23:434–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rotoli BT, Lima DA, Pini NP, et al. Porcelain veneers as an alternative for aesthetics treatment: clinical report. Oper Dent. 2013;38:459–466. doi: 10.2341/12-382-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taskonak B, Sertgöz A. Two-year clinical evaluation of lithia-disilicate-based all-ceramic crowns and fixed partial dentures. Dent Mater. 2006;22:1008–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2005.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reshad M, Cascione D, Magne P. Diagnostic mock-ups as an objective tool for predictable outcomes with porcelain laminate veneers in aesthetically demanding patients: a clinical report. J Prosthet Dent. 2008;99:333–339. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(08)00056-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okida RC. The use of fragments of thin veneers as a restorative therapy for anterior teeth disharmony: a case report with 3 years of follow-up. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2012;13:416–420. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmitter M, Mussotter K, Rammelsberg P, et al. Clinical performance of extended zirconia frameworks for fixed dental prostheses: two-year results. J Oral Rehabil. 2009;36:610–615. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2009.01969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Näpänkangas R, Raustia A. Twenty-year follow-up of metal-ceramic single crowns: a retrospective study. Int J Prosthodont. 2007;21:307–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abramson J, Abramson Z. Research methods in community medicine: surveys, epidemiological research, programme evaluation, clinical trials. Hoboken: Wiley; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petersen PE. Dental health behaviour among 25–44-year-old Danes. Scand J Prim Health Care. 1986;4:51–57. doi: 10.3109/02813438609013971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dragheim E, Petersen PE, Kalo I, et al. Dental caries in schoolchildren of an Estonian and a Danish municipality. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2000;10:271–277. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-263x.2000.00209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]