Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Our goal is to test the efficacy of a family-based, multi-component intervention focused on infants of African-American (AA) mothers and families, a minority population at elevated risk for pediatric obesity, versus a child safety attention-control group to promote healthy weight gain patterns during the first two years of life.

DESIGN, PARTICIPANTS, AND METHODS

The design is a two-group randomized controlled trial among 468 AA pregnant women in central North Carolina. Mothers and study partners in the intervention group receive anticipatory guidance on breastfeeding, responsive feeding, use of non-food soothing techniques for infant crying, appropriate timing and quality of complementary feeding, age-appropriate infant sleep, and minimization of TV/media. The primary delivery channel is 6 home visits by a peer educator, 4 interim newsletters and twice-weekly text messaging. Intervention families also receive 2 home visits from an International Board Certified Lactation Consultant. Assessments occur at 28 and 37 weeks gestation and when infants are 1, 3, 6, 9, 12, and 15 months of age.

RESULTS

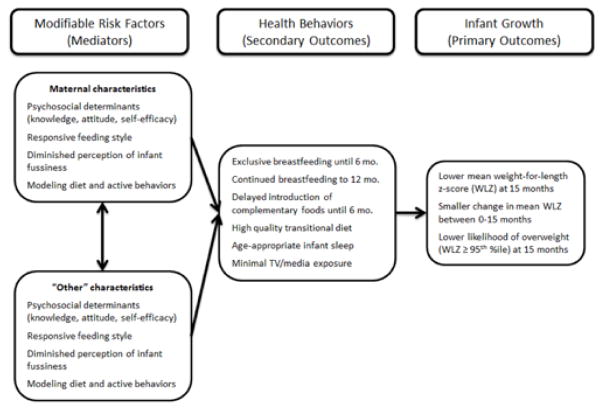

The primary outcome is infant/toddler growth and likelihood of overweight at 15 months. Differences between groups are expected to be achieved through uptake of the targeted infant feeding and care behaviors (secondary outcomes) and change in caregivers’ modifiable risk factors (mediators) underpinning the intervention.

CONCLUSIONS

If successful in promoting healthy infant growth and enhancing caregiver behaviors, “Mothers and Others” will have high public health relevance for future obesity-prevention efforts aimed at children younger than 2 years, including interventional research and federal, state, and community health programs.

Keywords: infancy, obesity, breastfeeding, complementary feeding, television, social support

BACKGROUND

There has been an approximate 60% increase in overweight among infants and toddlers in the past few decades.1,2 This is concerning given research suggesting obesity is intractable; both large infant size and rapid postnatal growth are associated with subsequent child and adult overweight3,4 and future co-morbidities, including hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and Type 2 diabetes.5,6

Research into the causes of large infant size and rapid growth has steadily increased.3,7,8 Promising behavioral determinants include short durations of exclusive or any breastfeeding,9 introduction of complementary foods (CF) before 4 months,10 shorter sleep duration among older infants and young children,11,12 early emergence of obesogenic diets (i.e., low fruit and vegetable intake; high intake of fatty/sugary snack foods, fast foods, juice, and sugar-sweetened beverages [SSBs]),13–18 and higher levels of television (TV)/media time.19–21 Importantly, there is growing evidence on the modifiable factors associated with these early life feeding and care behaviors, providing insight into potential avenues for intervention.

Modifiable factors include psychosocial constructs from health behavior theories (attitude, intention, and self-efficacy),22–25 parental feeding styles (responsive feeding),26–33 and interpretation of infant fussiness.34–39 Specific to breastfeeding, substantial evidence shows that more positive attitudes, greater levels of social support, and greater breastfeeding self-efficacy are each associated with higher rates of breastfeeding initiation and/or longer durations of exclusive or partial breastfeeding.22–25

Similarly, feeding styles are latent constructs characterizing caregivers based on their beliefs and behaviors.26 Research over the last three decades has culminated in a comprehensive set of caregiver feeding styles,27 including those our team has adapted and validated for use with caregivers of infants and toddlers (Table 1).28 Notably, each of the less responsive feeding styles (i.e., controlling, pressuring, indulgent, and laissez-faire) has been associated with one or more outcomes among preschoolers as well as infants and toddlers, including dysregulation of appetite and higher energy intakes,29–31 lower intake of fruits and vegetables,32 higher intake of junk-type foods,33 and greater adiposity.33

Table 1.

Caregiver feeding styles and definitions from the Infant Feeding Styles Questionnaire (IFSQ)28

| Feeding Style | Definition |

|---|---|

| Responsive | Caregiver is attentive to child’s hunger and satiety cues and monitors the quality of the child’s diet. |

| Restrictive (Controlling) | Caregiver limits the infant to healthful foods and limits the quantity of food consumed. |

| Restrictive (Pressuring) | Caregiver is concerned with increasing the amount of food the infant consumes and uses food to soothe the infant. |

| Indulgent | Caregiver does not set limits on the quantity or quality of food consumed. |

| Laissez-Faire | Caregiver does not limit the infant’s diet quality or quantity and shows little interaction with the infant during feeding. |

The importance of parental perception of infant temperament on early feeding behaviors has become increasingly clear. Multiple studies show caregivers use infant fussing and crying as a cue an infant is hungry and/or it is time to introduce CF,34–37 and the use of food to soothe infant/toddler distress has been associated with higher child weight status.38,39 Among toddlers, internalized negative emotionality, being sad/fearful/anxious, and externalized negative emotionality, being defiant/aggressive, have each been associated with feeding of sweet foods, sweet drinks, and night-time caloric drinks.40

While interventions targeting the first two years of life have increased dramatically over the last decade,41,42 critical gaps remain. First, most interventions begin after three or more months of infant age, missing an important opportunity to promote breastfeeding, responsive feeding, and healthy infant sleep behaviors in the early postpartum period. Pregnancy is also a teachable moment, a “naturally occurring life transition or health event thought to motivate individuals to spontaneously adopt risk-reducing health behaviors” (p.156).43 Second, there is limited engagement of non-maternal caregivers in interventions. Nearly half of all infants and toddlers are in regular non-maternal care, most frequently by relatives,44 who are actively involved in feeding.45 The influence of fathers and grandmothers on infant feeding and care decisions has been well-documented,34,46–49 making it essential to involve other caregivers in early life obesity prevention efforts. Third, few interventions have directly targeted infant behavior, an important limitation given research on caregivers’ use of suboptimal feeding practices, including early cessation of breastfeeding and adding infant cereal in the bottle.34–37,40

One priority population for intervention is African-American (AA) families, as AA infants, compared to white infants, have a higher prevalence of obesity2 and are twice as likely to experience rapid weight gain in the first six months of life.50 AA mothers have lower rates of breastfeeding across all nationally reported indicators,51 and our preliminary work with AA mothers has documented a normative pattern of feeding CF as early as 7–10 days postpartum,52 a common practice of feeding cereal in the bottle,37,52 and a predominant feeding pattern of formula, solids, and juice by 3 months of age.8,37 AA infants are also significantly more likely than white infants to have a daily sleep duration of < 12 hours, to have a TV in the bedroom, and to consume SSBs and fast food.50,53

Conceptual framework

The conceptual framework underpinning the design of this study (Figure 1) is informed by the aforementioned literature, preliminary data from an observational, longitudinal study,8,21,28,31,37,45 and a transdisciplinary set of theoretical frameworks. From developmental psychology, we include parental feeding styles, which are feeding domain-specific parenting styles similar to those developed by Birch and Johnson (1995)26 for older children and based on the seminal work of Baumrind (1971) and Maccoby and Martin (1983) that defined general parenting styles and their relationships to child development outcomes.54,55 From biomedicine, we incorporate anticipatory guidance (AG), information given to families about what to expect in their child’s development and how to promote it;56 which has been associated with improved parental knowledge of child development,57,58 higher quality parent-child interactions,59–61 and better infant sleep patterns.62–64 Additionally, two recently completed randomized controlled trials (RCTs) aimed at early life obesity prevention utilized AG,65,66 each documenting improvements in parental responsive feeding practices,67–69 infant preference for fruit,68 and decreased intake of SSBs and snacks.68,70 From health behavior and health education, we build on behavioral constructs from Social Cognitive Theory71 and the theory of Social Networks and Social Support72 that are associated with better infant care and feeding outcomes, including outcome expectations/attitudes,22,73,74 self-efficacy,22,46,75,76 and social support.46,47,77

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework underpinning the “Mothers & Others” intervention.

Aims and hypotheses

The aim of this study is to compare the effect of a home-based, multi-component intervention for AA pregnant women and families, versus an attention-control, on: infant size and growth (primary outcomes); infant diet, sleep and TV/media (secondary outcomes); and, caregiver behavioral and psychosocial constructs (mediators). Pregnant AA women are randomized to one of two study groups:

Early life obesity prevention consisting of home visits delivered by a trained peer educator (PE), newsletters, reinforcing text messages, and identification of a study partner, who receives study materials and is encouraged to actively participate in the study alongside the mother;

Attention-control group on child safety also consisting of PE-delivered home visits, newsletters, reinforcing text messages, and identification of a study partner, who only completes study assessments.

We hypothesize that, relative to the attention control:

Infants of families in the intervention group will display significantly healthier growth outcomes, including: 1) lower mean weight-for-length z-score (WLZ) at 15 months; 2) smaller change in WLZ between 0–15 months; and, 3) lower likelihood of overweight (WLZ ≥ 95th percentile) at 15 months.

Intervention caregivers will report significantly greater achievement of the targeted health behaviors: breastfeeding, appropriate timing and quality of CF, fewer reports of infant sleep problems, and lower levels of infant TV/media.

Intervention caregivers will have improved diet, physical activity, and TV/media behaviors, more positive breastfeeding attitudes and higher maternal breastfeeding self-efficacy, greater knowledge of intervention messages, more responsive feeding styles, and diminished perceptions of infant fussiness.

Intervention mothers will report higher levels of perceived social support from family.

DESIGN AND METHODS

Overall study design

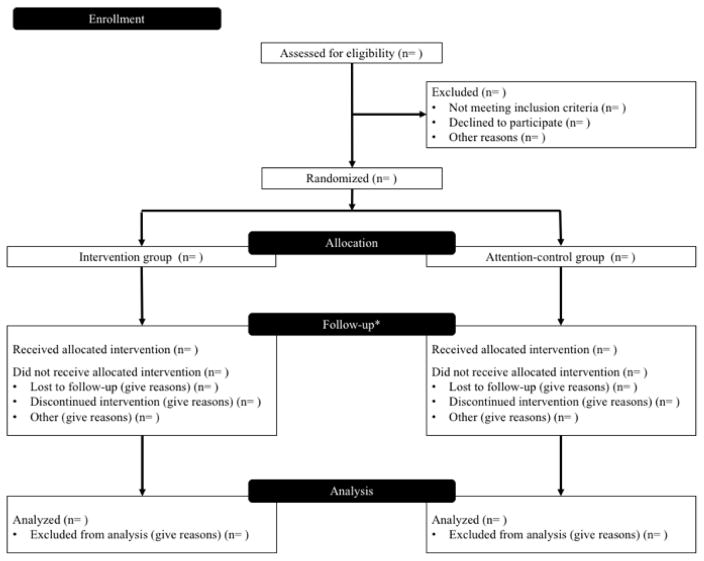

The study design is a two-group RCT with an attention-control child safety group and a targeted sample of 468 AA pregnant women and families living in central North Carolina. Figure 2 illustrates the intervention and assessment activities by study arm. The study begins when women are 28 weeks gestation (baseline) and has a final assessment when infants are 15-months-old, with interim assessments at 37 weeks gestation and when infants are 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months of age. The primary delivery channel is home visits, supplemented by newsletters and twice-weekly text messaging. Funding for this 5-year project comes from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD073237). Institutional review board approval has been granted by the University of North Carolina, Office of Human Research Ethics.

Figure 2.

CONSORT flow diagram of intervention and assessment activities by study arm

Participants and recruitment

Pregnant AA women planning to deliver at three local hospitals are primarily recruited by trained recruitment specialists in prenatal clinics. These efforst are supplemented with flyers posted in community-based locations (e.g. churches, libraries) and announcements to parenting listservices. Eligible women are ages 18–39 years, have a singleton pregnancy, speak English, are <28 weeks gestation, are planning to stay in the area, and can identify a study partner. Exclusion-criteria include premature birth (<36 weeks), the mother or infant having a hospital stay after delivery >7 days, birthweight <2500 grams, or diagnosis of a congenital anomaly or condition significantly affecting feeding or growth (e.g., Down’s syndrome, cleft lip or palate).

Sample size

The sample size of 468 families is based on power analyses showing a minimum of 354 mother-infant pairs (177 per group) allows detecttion of an effect size of ≥0.30 in infant WLZ at 15 months. This is based on an estimated mean WLZ of 0.34 and a standard deviation of 1.04 from our preliminary observational cohort study in a similar population.8,21,28,31,37,45 To achieve the minimum sample size of 354 infants at study end, we have incorporated a 12% loss of mothers, who may become ineligible to participate after enrollment due to meeting one or more birth-related exclusion criteria, as well as a sample attrition rate of 20%.

Randomization

Due to the influence of hospital practices on breastfeeding outcomes,78 randomization is stratified by hospital using a computer generated sequence and block size of 50. Allocation concealment is ued to prevent the PEs and participants from knowing which group families will be assigned. The project director, who has no direct contact with study participants, is responsible for generating the random number table and uploading it to REDCap,79 a secure, online database maintained by the Center for Translational and Clinical Sciences Institute at UNC (1UL1TR001111 from the Clinical and Translational Science Award program of the Division of Research Resources, National Institutes of Health [NIH]). All baseline assessments are conducted in the home by one of the trained PEs, after informed consent is given. At the completion of the baseline assessment, the PE randomizes the participant using the randomization functionality in REDCap. Blinding is not maintained for PEs and participants after allocation as participants are made aware of the intervention groups during the consent process and PEs deliver the differing intervention content. Afer randomization, participants complete all surveys online or via mail-based paper surveys prior to each educational home visit. PEs only collect objective, anthropometric data. Dietary recall data collectors are blinded to intervention group. All study data is maintained in REDCap.79

Intervention group

Intervention participants receive 8 home visits, an information toolkit, 4 newsletters and twice-weekly text messages designed to provide AG and support for enactment of the 6 targeted infant feeding and care behaviors: breastfeeding; adoption of a responsive feeding style; use of non-food soothing techniques for infant crying; appropriate timing and quality of CF; minimization of TV/media; and, promotion of normal infant sleep. To increase social support for the targeted behaviors, study partners are encouraged to attend all home visits, are provided their own informational toolkit and series of newsletters, and are encouraged to sign up for reinforcing text messages. Mothers are given the opportunity to change their study partner at three time points over the course of the intervention: 3, 6, and 9 months postpartum.

Delivery channels

The primary delivery channel is home visitation. Six home visits are delivered by a PE at 30 and 34 weeks gestation and 3, 6, 9, and 12 months postpartum. The PE is an AA mother, who breastfed her own children and received over 100 hours of training in breastfeeding, CF, and infant behavior during the first 6 months of study preparation. Participants are offered enhanced lactation support services, consisting of up to 2 additional home visits by an International Board Certified Lactation Consultant after hospital discharge.

Home visits are reinforced through an informational toolkit provided to mothers and study partners at the first prenatal home visit. The toolkit is titled “My Guide to Growing [NAME OF INDEX CHILD] Healthy” and is organized according to the home visitation schedule. Each section contains a bullet-pointed summary of key messages covered during the home visit and a combination of supplementary resources carefully selected or developed by our team of experts. Prior to each postpartum home visit, mothers and study partners also receive a newsletter focused on CF. The series of 4 newsletters, titled “My Great Eating Adventure,” is organized around key developmental stages: head up (less than 6 months), learning to sit (6–8 months), learning to crawl (8–10 months), and learning to walk (10–12 months). One-way text messages reinforce content delivered through home visits and newsletters.

Curriculum content

The AG curriculum and text messages for the current study were informed by several expert resources, including the Baby Behavior program,80 Ages & Stages Learning Activities,81 the Start Healthy Feeding Guidelines82 and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Nutrition Handbook.83 Baby Behavior is a curriculum and programmatic approach developed to address the growing evidence that caregivers implement suboptimal feeding practices in response to infant behavioral traits (crying/fussing) or to achieve a desired outcome (extending infant nocturnal sleep).35 Organized around three topic areas (cues, crying, and sleep), Baby Behavior teaches caregivers: how to recognize and respond appropriately to infant hunger and fullness cues and signs of engagement (when an infant wants to play) and disengagement (when an infant needs a break); typical patterns of infant sleep and how to recognize and respond appropriately to different phases of infant sleep (active and dreaming versus light and easy-to-waken); and the variety of reasons for which an infant might cry and how to recognize and respond appropriately to infant crying that is not related to hunger.

The importance of minimizing TV/media is embedded within the Baby Behavior program. Caregivers are encouraged to keep TV/media out of the infant’s bedroom and to reduce infant exposure to screen time as a tool for promoting normal, healthy sleep. Caregivers are encouraged to turn off TV/media during meals and snacks to minimize distractions for both the caregiver and infant, providing an environment in which modeling, mealtime learning, and recognition of hunger and fullness cues is more likely to occur. Caregivers are shown vignettes of parents interacting with infants and promoting activity in easy ways, including eye contact, conversation, and mat play. The Ages & Stages Learning Activities, created by developmental experts to promote parent-child interactions across five developmental domains (communication, gross motor, fine motor, problem solving, and personal-social) provide additional ideas for engaging with infants to promote development. The activities utilize safe and age-appropriate materials that are common in most households.

The Start Healthy Feeding Guidelines and the AAP Nutrition Handbook informed the curriculum on CF, particularly the new types of foods and textures that are appropriate and safe at each developmental stage. Caregivers are encouraged to begin with small amounts (teaspoons) of CF and to use their infant’s cues to decide to feed a smaller or greater amount. Iron-rich foods are encouraged first, followed by a gradual introduction, in no particular order, of healthy foods, such as modified whole fruits and vegetables. Caregivers are encouraged early in the postpartum period to make healthful changes to their own diet, as infants are likely to be exposed to and fed the types of foods commonly consumed by the family. Areas of focus include: increasing fruits and vegetables, decreasing sugar-sweetened beverages, choosing lean protein foods, making healthier choices when eating out, and choosing healthy snacks. Participants set small goals and are provided a goal setting and tracking calendar. Goal progress is assessed at each subsequent postpartum home visit and new goals are set accordingly. A similar process is followed for family physical activity, TV/media, and family meals. An overview of the curriculum for all home visits, by study arm, is presented in Table 2, with more detailed examples of the curriculum in the supplementary file.

Table 2.

Intervention content for home visits, by timing of delivery and study arm

| Home Visit (Timing) | Obesity Prevention Group (Intervention Arm) | Injury Prevention Group (Attention Control Arm) |

|---|---|---|

| PRENATAL | ||

| Home Visit 1 (30 weeks) | Baby behavior (cues, crying, and sleep) 0–6 months

|

Preventing SIDS and accidental suffocation Tips for selecting a crib Introducing you to your toolkit: finding more information |

| Home Visit 2 (34 weeks) | Baby behavior: the first 72 hours

|

Choosing and using a safe car seat Safety in and around the car Keeping baby safe in a stroller |

| POSTNATAL | ||

| Home Visit 3 (3 months) | Let’s catch up!

|

Let’s catch up! safe sleep and safety-on-the-go Top safety tips for 1–6 months: the “head up” stage Getting ahead on safety: childproofing your home for the “independent sitter” stage |

| Home Visit 4 (6 months) | Let’s review: your 5-month newsletter (learning to sit)

|

Let’s review: top safety tips for the “independent sitter” stage Getting ahead on safety: childproofing your home for the “crawler” stage Home fire safety: prepare, practice, prevent the unthinkable |

| Home Visit 5 (9 months) | Healthy eating and being active: it’s all in the family (checking in)

|

Let’s review: top safety tips for the “crawler” stage Getting ahead on safety: childproofing your home for the “learning to walk” stage Preventing TV tip-overs: what every parent should know |

| Home Visit 6 (12 months) | Healthy eating and being active: it’s all in the family (checking in)

|

Let’s review: childproofing your home Splish-splash: Staying safe around water Bye-bye boo-boos: staying safe on the playground |

Control group

Content for the attention-control group is based on the child safety and injury prevention AG published in AAP Bright Futures.84 The PE for the control group is AA, has previous experience in the supervision of young children, and received over 100 hours of training during the study preparation phase in the prevention of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, proper installation of infant car safety seats, and household injury prevention measures. Mothers in the attention-control group receive the same number of home visits, newsletters and text messages. While mothers in the control group also identify a study partner, they only complete study assessments: they are not encouraged to attend home visits or given the opportunity to sign up for text messages.

Measures

Study measures are outlined in Table 3. Primary outcomes include lower WLZ at 15 months, smaller change in WLZ between 0–15 months, and lower likelihood of overweight (WLZ ≥ 95th percentile) at 15 months. WLZ scores are calculated using the World Health Organization 2006 international growth standards.85 Infant birth weight and length are self-reported by mothers, with a subset abstracted from hospital records to verify accuracy. Anthropometrics at subsequent time points are directly measured by the PEs, who are trained according to guidelines used in the existing National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.86

Table 3.

Study measures and assessment timetable

| Measure | Source/Instrument (where applicable) | Assessment Time Point

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prenatal (weeks)

|

Postnatal (months)

|

||||||||||

| 28 | 30 | 34 | 37 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 12 | 15 | ||

| Background informationa | X | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Primary outcome | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Infant weight-for-length | Direct measurement of anthropometrics85,86 | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Secondary outcomes | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Infant dietary intake | Infant Feeding Practices Study-II87 | X | X | X | X | X | Xb | ||||

| Infant TV and electronic media exposure | Questions from previous studies90–95 | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Infant sleep | Brief Infant Sleep Questionnaire96–98 | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Mediators | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Maternal infant feeding intentions | Infant Feeding Intentions Scale101 | X | X | ||||||||

| Caregiver breastfeeding attitudec | Iowa Infant Feeding Attitudes Scale102 | X | X | ||||||||

| Maternal breastfeeding self-efficacy | Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy-Short Form103 | X | |||||||||

| Maternal parenting self-efficacy | Parenting Self-Efficacy Scale104,105 | ||||||||||

| Caregiver feeding responsivenessc | Infant Feeding Styles Questionnaire8 | ||||||||||

| Responsiveness to Child Feeding Cues Scale106 | Xd | Xd | Xe | X | Xe | X | Xe | ||||

| Caregiver perception of infant temperamentc | Infant Behavior Questionnaire-Revised107 | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Maternal perceived social support | Perceived Social Support from Family108 | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Caregiver KAB of intervention messagesc,f | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Caregiver dietary intakec | Starting the Conversation109 | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Caregiver physical activityc | International Physical Activity Questionnaire110 | X | X | X | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Additional measures: | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Caregiver body mass index c | Direct measurement of anthropometrics85 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Caregiver depressionc | Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression111 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

|

| |||||||||||

| Process measures: | |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Treatment fidelity (adherence, exposure)h | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Participant satisfactionh | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

Demographics, household composition, food security, employment history, available maternal leave, health history, current health status and paternal self-reported height and weight

The assessment for the study partner, in both intervention arms, also contains this measure, except for anthropometrics; study partners self-report height and weight

During pregnancy, the assessment only includes items on infant feeding beliefs

Includes video observation of a feeding episode and analysis using the Responsiveness to Child Feeding Cues Scale106

KAB = knowledge, attitudes, beliefs

Includes an assessment by the home visitor as to whether or not the study partner was in attendance

Study partners in the intervention arm, but not the attention-control arm, also complete a satisfaction survey

Secondary outcomes include infant diet, TV/media exposure, and sleep. All measures are self-reported by mothers and study partners via online surveys taken prior to each postpartum home visit and at study end. Mothers also complete a survey at 1 month postpartum to assess hospital experiences and early feeding and care practices. Infant diet outcomes include exclusive breastfeeding until 3 and 6 months, duration of any breastfeeding, timing of introduction of CF, and intake of select CF at 15 months (fruits and vegetables, desserts and sweets, chips and salty snacks). Infant dietary intake is measured in two ways: an infant diet history adapted after the Infant Feeding Practices II Study87 and, at 15 months, a series of two 24-hour dietary recalls88,89 administered by the UNC Diet, Physical Activity and Body Composition Core (NIH grant DK56350). Infant TV/media exposure is measured using questions from previous studies associating TV/media with infant diet and size,90–95 and infant sleep is assessed by the Brief Infant Sleep Questionnaire.96–98

Mediating variables related to caregiver psychosocial and behavioral determinants are collected via online surveys occurring at each data collection time point. Process measures capturing intervention fidelity and participant satisfaction are completed by home visitors and mothers at the end of each home visit. Study partners in the intervention arm also complete process measures.

Statistical analysis plan

A detailed analysis plan has been developed. While randomization should equalize important baseline characteristics across groups, we will begin analyses by testing for differences between groups and adjust for these variables in subsequent analyses as appropriate. The primary efficacy analysis will be a linear mixed model (LMM) on an intention-to-treat dataset with WLZ score at birth, 3, 6, 9, 12, and 18 months as the dependent variable and treatment group, age and their interaction term as the independent variables. LMM will be used to assess the effect of treatment group on change in WLZ and a generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) for likelihood of overweight. Secondary analyses will use LMM and GLMM to determine the effect of treatment group on continuous and categorical targeted health behaviors, respectively. For health behaviors found significantly different between groups, an additional set of mixed models will determine their impact on WLZ. Mediational analyses as described by Baron and Kenny (1986) and MacKinnon, Krull and Lockwood (2000) will determine the extent to which underlying psychosocial and behavioral determinants mediate the relationship between treatment group and targeted health behaviors.

Conclusion

“Mothers and Others” is an efficacy trial of a multi-component, home-based intervention focused on infants of AA mothers and families, a minority population at elevated risk for pediatric obesity. “Mothers and Others” advances the field by addressing critical gaps in family-based interventions aimed at early life obesity prevention, namely beginning during pregnancy, a “teachable moment,” increasing maternal social support for the enactment of healthy infant feeding and care behaviors through the engagement of a study partner, and incorporating a unique curriculum on infant behavior and responsive feeding that is grounded in developmental science. If successful in promoting healthy infant growth and enhancing caregiver health behaviors, “Mothers and Others” will have high public health relevance for future obesity-prevention efforts aimed at children less than two years, including interventional research and federal, state, and community health programs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, grant number R01HD073237, 2012–2017

Abbreviations

- AA

African-American

- CF

complementary feeding/foods

- SSB

sugar-sweetened beverage

- TV

television

- AG

anticipatory guidance

- PE

peer educator

- WLZ

weight-for-length z-score

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- NIH

National Institutes of Health

- AAP

American Academy of Pediatrics

Footnotes

Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT01938118, August 9, 2013

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in overweight among US children and adolescents, 1999–2000. JAMA. 2002;288(14):1728–1732. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of Childhood and Adult Obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA. 2014;311(8):806–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woo Baidal JA, Locks LM, Cheng ER, Blake-Lamb TL, Perkins ME, Taveras EM. Risk Factors for Childhood Obesity in the First 1,000 Days: A Systematic Review. Am J Prev Med. 2016 Jun;50(6):761–779. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simmonds M, Llewellyn A, Owen CG, Woolacott N. Predicting adult obesity from childhood obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2016 Feb;17(2):95–107. doi: 10.1111/obr.12334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Llewellyn A, Simmonds M, Owen CG, Woolacott N. Childhood obesity as a predictor of morbidity in adulthood: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2016 Jan;17(1):56–67. doi: 10.1111/obr.12316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prospective Studies Collaboration. Whitlock G, Lewington S, et al. Body-mass index and cause-specific mortality in 900,000 adults: collaborative analyses of 57 prospective studies. Lancet. 2009 Mar 28;373(9669):1083–1096. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60318-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weng SF, Redsell SA, Swift JA, Yang M, Glazebrook CP. Systematic review and meta-analyses of risk factors for childhood overweight identifiable during infancy. Arch Dis Child. 2012 Dec;97(12):1019–1026. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2012-302263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thompson AL, Bentley ME. The critical period of infant feeding for the development of early disparities in obesity. Soc Sci Med (1982) 2013;97:288–296. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJD, et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet. 2016;387(10017):475–490. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agostoni C, Przyrembel H. The timing of introduction of complementary foods and later health. World Rev Nutr Diet. 2013;108:63–70. doi: 10.1159/000351486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taveras EM, Rifas-Shiman SL, Oken E, Gunderson EP, Gillman MW. Short sleep duration in infancy and risk of childhood overweight. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(4):305–311. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.4.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taveras EM, Gillman MW, Peña M-M, Redline S, Rifas-Shiman SL. Chronic Sleep Curtailment and Adiposity. Pediatrics. 2014;133(6):1013–1022. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fletcher S, Wright C, Jones A, Parkinson K, Adamson A. Tracking of toddler fruit and vegetable preferences to intake and adiposity later in childhood. Matern Child Nutr. 2016 Apr 4; doi: 10.1111/mcn.12290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grimm KA, Kim SA, Yaroch AL, Scanlon KS. Fruit and vegetable intake during infancy and early childhood. Pediatrics. 2014 Sep;134(Suppl 1):S63–69. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0646K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sonneville KR, Long MW, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kleinman K, Gillman MW, Taveras EM. Juice and water intake in infancy and later beverage intake and adiposity: Could juice be a gateway drink? Obesity. 2015;23(1):170–176. doi: 10.1002/oby.20927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park S, Pan L, Sherry B, Li R. The Association of Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Intake During Infancy With Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Intake at 6 Years of Age. Pediatrics. 2014;134(Suppl 1):S56–S62. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0646J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pan L, Li R, Park S, Galuska DA, Sherry B, Freedman DS. A Longitudinal Analysis of Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Intake in Infancy and Obesity at 6 Years. Pediatrics. 2014;134(Suppl 1):S29–S35. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0646F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saavedra JM, Deming D, Dattilo A, Reidy K. Lessons from the feeding infants and toddlers study in North America: what children eat, and implications for obesity prevention. Ann Nutr Metab. 2013;62(Suppl 3):27–36. doi: 10.1159/000351538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dennison BA, Erb TA, Jenkins PL. Television viewing and television in bedroom associated with overweight risk among low-income preschool children. Pediatrics. 2002;109(6):1028–1035. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.6.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Certain LK, Kahn RS. Prevalence, correlates, and trajectory of television viewing among infants and toddlers. Pediatrics. 2002 Apr;109(4):634–642. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.4.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thompson AL, Adair LS, Bentley ME. Maternal Characteristics and Perception of Temperament Associated with Infant TV Exposure. Pediatrics. 2013;131(2):e390–e397. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Jager E, Broadbent J, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M, Skouteris H. The role of psychosocial factors in exclusive breastfeeding to six months postpartum. Midwifery. 2014 Jun;30(6):657–666. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2013.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nnebe-Agumadu UH, Racine EF, Laditka SB, Coffman MJ. Associations between perceived value of exclusive breastfeeding among pregnant women in the United States and exclusive breastfeeding to three and six months postpartum: a prospective study. Int Breastfeed J. 2016;11:8. doi: 10.1186/s13006-016-0065-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roll CL, Cheater F. Expectant parents’ views of factors influencing infant feeding decisions in the antenatal period: A systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016 Aug;60:145–155. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Emmott EH, Mace R. Practical Support from Fathers and Grandmothers Is Associated with Lower Levels of Breastfeeding in the UK Millennium Cohort Study. In: Raju T, editor. PLoS ONE. 7. Vol. 10. 2015. p. e0133547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Birch LL, Fisher JA. Appetite and eating behavior in children. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1995;42(4):931–953. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)40023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hughes SO, Cross MB, Hennessy E, Tovar A, Economos CD, Power TG. Caregiver’s Feeding Styles Questionnaire: Establishing Cutoff Points. Appetite. 2012;58(1):393–395. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thompson AL, Mendez MA, Borja JB, Adair LS, Zimmer CR, Bentley ME. Development and validation of the infant feeding style questionnaire. Appetite. 2009;53(2):210–221. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DiSantis KI, Hodges EA, Johnson SL, Fisher JO. The role of responsive feeding in overweight during infancy and toddlerhood: A systematic review. Int J Obes. 2011;35(4):480–492. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hurley KM, Cross MB, Hughes SO. A Systematic Review of Responsive Feeding and Child Obesity in High-Income Countries. J Nutr. 2011;141(3):495–501. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.130047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thompson AL, Adair LS, Bentley ME. Pressuring and restrictive feeding styles influence infant feeding and size among a low-income African-American sample. Obesity. 2013;21(3):562–571. doi: 10.1002/oby.20091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blissett J. Relationships between parenting style, feeding style and feeding practices and fruit and vegetable consumption in early childhood. Appetite. 2011 Dec;57(3):826–831. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.05.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kroller K, Warschburger P. Associations between maternal feeding style and food intake of children with a higher risk for overweight. Appetite. 2008;51(1):166–172. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bentley M, Gavin L, Black MM, Teti L. Infant feeding practices of low-income, African-American, adolescent mothers: An ecological, multigenerational perspective. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49(8):1085–1100. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00198-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heinig MJ, Follett JR, Ishii KD, Kavanagh-Prochaska K, Cohen R, Panchula J. Barriers to compliance with infant-feeding recommendations among low-income women. J Hum Lact. 2006;22(1):27–38. doi: 10.1177/0890334405284333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hodges EA, Hughes SO, Hopkinson J, Fisher JO. Maternal decisions about the initiation and termination of infant feeding. Appetite. 2008;50(2–3):333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wasser H, Bentley M, Borja J, et al. Infants perceived as “fussy” are more likely to receive complementary foods before 4 months. Pediatrics. 2011;127(2):229–237. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stifter CA, Anzman-Frasca S, Birch LL, Voegtline K. Parent use of food to soothe infant/toddler distress and child weight status. an exploratory study. Appetite. 2011;57(3):693–699. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anzman-Frasca S, Liu S, Gates KM, Paul IM, Rovine MJ, Birch LL. Infants’ Transitions out of a Fussing/Crying State Are Modifiable and Are Related to Weight Status. Infancy. 2013;18(5):662–686. doi: 10.1111/infa.12002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vollrath ME, Tonstad S, Rothbart MK, Hampson SE. Infant Temperament is Associated with Potentially Obesogenic Diet at 18 Months. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011;6(2–2):e408–e414. doi: 10.3109/17477166.2010.518240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ciampa PJ, Kumar D, Barkin SL, et al. Interventions aimed at decreasing obesity in children younger than 2 years: A systematic review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(12):1098–1104. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Redsell SA, Edmonds B, Swift JA, et al. Systematic review of randomised controlled trials of interventions that aim to reduce the risk, either directly or indirectly, of overweight and obesity in infancy and early childhood. Matern Child Nutr. 2016;12:24–38. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pollak KI, Denman S, Gordon KC, et al. Is pregnancy a teachable moment for smoking cessation among US latino expectant fathers? A pilot study. Ethn Health. 2010;15(1):47–59. doi: 10.1080/13557850903398293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laughlin L. Who’s minding the kids? child care arrangements: Spring 2005/Summer 2006. Current Population Reports. 2010;(August) [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wasser HM, Thompson AL, Siega-Riz AM, Adair LS, Hodges EA, Bentley ME. Who’s feeding baby? Non-maternal involvement in feeding and its association with dietary intakes among infants and toddlers. Appetite. 2013;71:7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.06.096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meedya S, Fahy K, Kable A. Factors that positively influence breastfeeding duration to 6 months: a literature review. Women Birth. 2010;23(4):135–145. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Britton C, McCormick FM, Renfrew MJ, Wade A, King SE. Support for breastfeeding mothers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1):CD001141. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001141.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khandpur N, Blaine RE, Fisher JO, Davison KK. Fathers’ child feeding practices: a review of the evidence. Appetite. 2014 Jul;78:110–121. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mitchell-Box KM, Braun KL. Impact of male-partner-focused interventions on breastfeeding initiation, exclusivity, and continuation. J Hum Lact. 2013 Nov;29(4):473–479. doi: 10.1177/0890334413491833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Taveras EM, Gillman MW, Kleinman K, Rich-Edwards JW, Rifas-Shiman SL. Racial/ethnic differences in early-life risk factors for childhood obesity. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):686–695. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Racial and ethnic differences in breastfeeding initiation and duration, by state -- national immunization survey, united states, 2004–2008. MMWR. 2010;59(11):327–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bronner YL, Gross SM, Caulfield L, et al. Early introduction of solid foods among urban African-American participants in WIC. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;99(4):457–461. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(99)00112-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Taveras EM, Gillman MW, Kleinman KP, Rich-Edwards JW, Rifas-Shiman SL. Reducing Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Childhood Obesity: The Role of Early Life Risk Factors. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(8):731–8. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baumrind D. Current patterns of parental authority. Devel Psychol. 1971;4(1):100–103. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maccoby E, Martin J. Socialization in the context of the family: Parent-child interaction. In: Mussen P, editor. Handbook of Child Psychology. New York, NY: Wiley; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nelson CS, Wissow LS, Cheng TL. Effectiveness of anticipatory guidance: Recent developments. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2003;15(6):630–635. doi: 10.1097/00008480-200312000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chamberlin RW, Szumowski EK, Zastowny TR. An evaluation of efforts to educate mothers about child development in pediatric office practices. Am J Public Health. 1979;69(9):875–886. doi: 10.2105/ajph.69.9.875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chamberlin RW, Szumowski EK. A follow-up study of parent education in pediatric office practices: Impact at age two and a half. Am J Public Health. 1980;70(11):1180–1188. doi: 10.2105/ajph.70.11.1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Casey PH, Whitt JK. Effect of the pediatrician on the mother-infant relationship. Pediatrics. 1980;65(4):815–820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bristor MW, Helfer RE, Coy KB. Effects of perinatal coaching on mother-infant interaction. Am J Dis Child. 1984;138(3):254–257. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1984.02140410034012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Black MM, Teti LO. Promoting mealtime communication between adolescent mothers and their infants through videotape. Pediatrics. 1997;99(3):432–437. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.3.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pinilla T, Birch LL. Help me make it through the night: Behavioral entrainment of breast-fed infants’ sleep patterns. Pediatrics. 1993;91(2):436–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wolfson A, Lacks P, Futterman A. Effects of parent training on infant sleeping patterns, parents’ stress, and perceived parental competence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992;60(1):41–48. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Adair R, Zuckerman B, Bauchner H, Philipp B, Levenson S. Reducing night waking in infancy: A primary care intervention. Pediatrics. 1992;89(4 Pt 1):585–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Daniels LA, Magarey A, Battistutta D, et al. The NOURISH randomised control trial: Positive feeding practices and food preferences in early childhood - a primary prevention program for childhood obesity. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:387. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Campbell K, Hesketh K, Crawford D, Salmon J, Ball K, McCallum Z. The Infant Feeding Activity and Nutrition Trial (INFANT) an early intervention to prevent childhood obesity: Cluster-randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:103. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Daniels LA, Mallan KM, Nicholson JM, et al. An Early Feeding Practices Intervention for Obesity Prevention. Pediatrics. 2015 Jul;136(1):e40–49. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-4108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Daniels LA, Mallan KM, Battistutta D, et al. Child eating behavior outcomes of an early feeding intervention to reduce risk indicators for child obesity: the NOURISH RCT. Obesity. 2014 May;22(5):E104–111. doi: 10.1002/oby.20693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Daniels LA, Mallan KM, Nicholson JM, Battistutta D, Magarey A. Outcomes of an early feeding practices intervention to prevent childhood obesity. Pediatrics. 2013 Jul;132(1):e109–118. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Campbell KJ, Lioret S, McNaughton SA, et al. A parent-focused intervention to reduce infant obesity risk behaviors: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2013 Apr;131(4):652–660. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hall A, Wellman B. Social networks and social support. In: Cohen S, Syme L, editors. Social Support and Health. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mitchell-Box K, Braun KL, Hurwitz EL, Hayes DK. Breastfeeding Attitudes: Association Between Maternal and Male Partner Attitudes and Breastfeeding Intent. Breastfeed Med. 2013;8(4):368–373. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2012.0135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Scott JA, Shaker I, Reid M. Parental attitudes toward breastfeeding: their association with feeding outcome at hospital discharge. Birth. 2004 Jun;31(2):125–131. doi: 10.1111/j.0730-7659.2004.00290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Xu H, Wen LM, Rissel C. Associations of Parental Influences with Physical Activity and Screen Time among Young Children: A Systematic Review. J Obes. 2015;2015:546925. doi: 10.1155/2015/546925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hnatiuk JA, Salmon J, Campbell KJ, Ridgers ND, Hesketh KD. Tracking of maternal self-efficacy for limiting young children’s television viewing and associations with children’s television viewing time: a longitudinal analysis over 15-months. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:517. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1858-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li K, Jurkowski JM, Davison KK. Social Support May Buffer the Effect of Intrafamilial Stressors on Preschool Children’s Television Viewing Time in Low-Income Families. Childhood Obesity. 2013;9(6):484–491. doi: 10.1089/chi.2013.0071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pérez-Escamilla R, Martinez JL, Segura-Pérez S. Impact of the Baby-friendly Hospital Initiative on breastfeeding and child health outcomes: a systematic review. Matern Child Nutr. 2016 Jul;12(3):402–417. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap): A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009 Apr;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Heinig MJ, Bañuelos J, Goldbronn J, Kampp J. Fit WIC Baby Behavior Study: “Helping you understand your baby”. [Accessed July 4, 2016];United States Department of Agriculture WIC Works Resource System website. https://wicworks.fns.usda.gov/wicworks/Sharing_Center/gallery/FitWICBaby.htm. Published 2009.

- 81.Learning Activities. [Accessed July 4, 2016];Ages & Stages Questionnaires website. http://agesandstages.com/products-services/learning-activities/

- 82.Butte N, Cobb K, Dwyer J, et al. The start healthy feeding guidelines for infants and toddlers. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104(3):442–454. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition. Pediatric Nutrition Handbook. 6. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hagan JF, Shaw JS, Duncan PM, editors. Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents. 3. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Centers for Disease. Use of world health organization and CDC growth charts for children aged 0–59 months in the united states: Recommendations and reports. MMWR. 2010;59(rr09):1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics. National health and nutrition examination survey anthropometry protocol. Hyattsville, MD: United States Department of Health and Human Services, Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 2016. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_15_16/2016_Anthropometry_Procedures_Manual.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fein SB, Labiner-Wolfe J, Shealy KR, Li R, Chen J, Grummer-Strawn LM. Infant feeding practices study II: Study methods. Pediatrics. 2008;122(Suppl 2):S28–35. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1315c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Thompson FE, Subar AE. Dietary assessment methodology. In: Coulston AM, Boushey CJ, editors. Nutrition in the Prevention and Treatment of Disease. 2. San Diego, CA: Elsevier Academic Press; 2008. pp. 3–38. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ziegler P, Briefel R, Clusen N, Devaney B. Feeding infants and toddlers study (FITS): Development of the FITS survey in comparison to other dietary survey methods. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106(1 Suppl 1):S12–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Miller SA, Taveras EM, Rifas-Shiman SL, Gillman MW. Association between television viewing and poor diet quality in young children. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2008;3(3):168–176. doi: 10.1080/17477160801915935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gortmaker SL, Must A, Sobol AM, Peterson K, Colditz GA, Dietz WH. Television viewing as a cause of increasing obesity among children in the united states, 1986–1990. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1996;150(4):356–362. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170290022003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Robinson TN. Reducing children’s television viewing to prevent obesity: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1999;282(16):1561–1567. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Armstrong CA, Sallis JF, Alcaraz JE, Kolody B, McKenzie TL, Hovell MF. Children’s television viewing, body fat, and physical fitness. Am J Health Promot. 1998;12(6):363–368. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-12.6.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Adachi-Meija AM, Longacre MR, Gibson JJ, Beach ML, Titus-Ernstoff LT, Dalton MA. Children with a TV in their bedroom at higher risk for being overweight. Int J Obes. 2007;31(4):644–647. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gable S, Chang Y, Krull JL. Television watching and frequency of family meals are predictive of overweight onset and persistence in a national sample of school-aged children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107(1):53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sadeh A. A brief screening questionnaire for infant sleep problems: Validation and findings for an internet sample. Pediatrics. 2004;113(6):e570–577. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.6.e570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sadeh A, Mindell JA, Luedtke K, Wiegand B. Sleep and sleep ecology in the first 3 years: A web-based study. J Sleep Res. 2009;18(1):60–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mindell JA, Sadeh A, Kohyama J, How TH. Parental behaviors and sleep outcomes in infants and toddlers: A cross-cultural comparison. Sleep Med. 2010;11(4):393–399. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.MacKinnon DP, Krull JL, Lockwood CM. Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prev Sci. 2000;1(4):173–181. doi: 10.1023/a:1026595011371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Nommsen-Rivers LA, Cohen RJ, Chantry CJ, Dewey KG. The Infant Feeding Intentions scale demonstrates construct validity and comparability in quantifying maternal breastfeeding intentions across multiple ethnic groups. Matern Child Nutr. 2010 Jul 1;6(3):220–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2009.00213.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.De La Mora A, Russell DW. The Iowa infant feeding attitude scale: Analysis of reliability and validity. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1999;29(11):2362–2380. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Dennis CL. The breastfeeding self-efficacy scale: Psychometric assessment of the short form. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2003;32(6):734–744. doi: 10.1177/0884217503258459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Dennis CL. The breastfeeding self-efficacy scale: Psychometric assessment of the short form. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2003;32(6):734–744. doi: 10.1177/0884217503258459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Gibaud-Wallston JA. Doctoral dissertation. George Peabody College for Teachers; 1977. Self-esteem and situational stress: Factors related to sense of competence in new parents. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Johnston C, Mash EJ. A measure of parenting satisfaction and efficacy. J Clin Child Psychol. 1989;18:167–175. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hodges EA, Johnson SL, Hughes SO, Hopkinson JM, Butte NF, Fisher JO. Development of the Responsiveness to Child Feeding Cues Scale. Appetite. 2013;65:210–219. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Gartstein MA, Rothbart MK. Studying infant temperament via the revised infant behavior questionnaire. Infant Behav Devel. 2003;26(1):64–86. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Procidano ME, Heller K. Measures of perceived social support from friends and from family: Three validation studies. Am J Community Psychol. 1983;11(1):1–24. doi: 10.1007/BF00898416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Paxton AE, Strycker LA, Toobert DJ, Ammerman AS, Glasgow RE. Starting the conversation performance of a brief dietary assessment and intervention tool for health professionals. Am J Prev Med. 2011 Jan;40(1):67–71. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, et al. International Physical Activity Questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sport Exer. 2003;35:1381–1395. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psych Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.