Abstract

Objective

Laryngeal dystonia (LD) is a functionally specific disorder of the afferent-efferent motor coordination system producing action induced muscle contraction with a varied phenomenology. This report of long term studies aims to review and better define the phenomenology and CNS abnormalities of this disorder and improve diagnosis and treatment.

Methods

Our studies categorized over 1400 patients diagnosed with LD over the past 33 years, including demographic and medical history records and their phenomenological presentations.

Patients were grouped on clinical phenotype (adductor or abductor) and genotype (sporadic and familial) and with DNA analysis and fMRI to investigate brain organization differences and to characterize neural markers for genotype/phenotype categorization. A number of patients with alcohol sensitive dystonia were also studied.

Results

A spectrum of LD phenomena evolved- adductor, abductor, mixed, singer’s, dystonic tremor, and adductor respiratory dystonia. Patients were genetically screened for DYT1, DYT4, DYT6 and a DYT25 (GNAL) and several were positive. The functional MRI studies showed distinct alterations within the sensorimotor network and the LD patients with a family history had distinct cortical and cerebellar abnormalities. A linear discriminant analysis of fMRI findings showed a 71% accuracy in characterizing LD from normal and in characterizing adductor from abductor forms.

Conclusion

Continuous studies of LD patients over 30 years have led to an improved understanding of the phenomenological characteristics of this neurological disorder. Genetic and fMRI studies have better characterized the disorder and raises the possibility of making objective, rather than subjective diagnoses and potentially leading to new therapeutic approaches.

Keywords: Laryngeal Dystonia, Botulinum toxin, Dysphonia

Introduction

The purpose of this manuscript is to review many of our 30+ years of experience and concurrent studies of patients with laryngeal dystonia. It will review the evolution of the understanding of the phenomenology including altering the symptoms with Botulinum toxin. We also review the genetic studies and brain evaluations which ultimately will lead to a more objective diagnosis of this syndrome and provide targeted treatments of the functional brain abnormalities.

Historical Background

Laryngeal dystonia (LD) (known as Spasmodic Dysphonia) is a functionally specific movement disorder. The disorder has been long recognized but was not categorized as a focal dystonia until the late 1980’s.

The nomenclature of the disorder has undergone many iterations over time. Historically, dystonic voice alterations were first described as “Spastic dysphonia” by Traube in 1871 (1) when describing a patient with nervous hoarseness. Schnitzler (2) used the term “spastic aphonia” (now called abductor LD) and “phonic laryngeal spasms” (now called adductor LD). Nothnagel later called the condition “coordinated laryngeal spasms” while Fraenkel (3, 4) used the term “mogiphonia” for a slowly developing disorder of the voice characterized by increasing vocal fatigue, spasmodic constriction of the muscles of the throat, and pain around the larynx. He compared this disorder of the larynx to “mogigraphia” which we now know is a focal dystonia of the hand and arm called “writer’s cramp. In 1899, Gowers (5) described functional laryngeal spasms whereby the vocal cords were brought together too forcibly while speaking. He contrasted this to phonic paralysis, where the vocal cords could not be brought together while speaking (again describing what we now call the adductor and abductor forms). Gowers went on to report that the vocal symptoms can be compared to writer’s cramp. He described a case reported by Gerhardt, in which the patient had actually suffered from writer’s cramp, and at the age of 50, learned to play the flute. The act of blowing the flute brought on laryngeal spasms and an unintended voice sound, accompanied by muscular contractions in the arm and angle of the mouth. Here again, the focal dystonia of the larynx is being compared to dystonia involving other segments of the body (mouth and arm). In his textbook, Critchley (6) described the voice pattern as a condition in which the patient sounds as though he was trying to “speak wilst being choked”, Bellussi (7) described the condition as “stuttering with the vocal cords”. This disorder was originally termed “spastic dysphonia” and then, since it was not a disorder with spasticity, was re-named “spasmodic dysphonia” by Aronson (8). In the late 1980s, Jacome and Yanez, at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Med Center, David Marsden’s group at Queen’s Square Hospital in London, and our group at Columbia first categorized this disorder as a focal dystonia (9,10,11,12).

In an early work, Aronson, performed Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) screening and reviewed psychiatric interviews of spasmodic dysphonia patients and found no difference from the normal population, thereby helping to establish that spasmodic dysphonia is not a psychiatric disorder. Aronson also formally characterized 2 types: an adductor form due to irregular hyperadduction of the vocal folds, and abductor due to intermittent abduction of the vocal folds. He described the adductor type as a choked, strain-strangled voice quality with abrupt initiation and termination of sound, producing voice breaks. The voice had decreased loudness and a monotonality. A vocal tremor was often heard with a slowed speech rate. Aronson later compared this tremor to that seen in essential tremor. On the other hand, he characterized the voice of patients with abductor LD as breathy with effortful vocalization and abrupt termination of voicing producing aphonic, whispered segments of speech. (8,13).

Dystonia is a disorder of the afferent sensory-efferent motor coordination system producing action induced sustained muscle contraction causing abnormal postures or repetitive movements that may be intermittent, affecting any voluntary group of muscles. Some forms of focal dystonia, like LD and writer’s cramp, are action induced and task specific movement disorders. In the case of LD, the task, or action, is phonation, or active functional use of the vocal musculature. Isolated dystonia may occur at any age, but generalized dystonia tends to onset in childhood whereas focal dystonias tend to occur in the 3rd to 4th decade. There are a number of suspected etiologies in secondary or acquired dystonia including hereditary forms and environmental (trauma, infections, vascular, tumors, toxins and drugs). Greater than 60% are termed idiopathic (14, 15) (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Classification of Dystonia

| I- Focal Dystonias: |

| 1. Blepharospasm |

| 2. Oromandibulolingual Dystonia |

| 3. Cervical Dystonia (torticollis) |

| 4. Hand Dystonia (writer’s cramp) |

| 5. Laryngeal Dystonia (Spasmodic Dysphonia) |

| a. adductor type |

| b. abductor type |

| c. mixed type |

| d. singer’s dystonia |

| e. adductor respiratory dystonia |

| II- Segmental Dystonia (Multi-cranial–Meige syndrome) |

| III- Generalized Dystonia |

Our group, studying SD (Spasmodic Dysphonia) patients clinically and with electromyography (EMG), confirmed that SD was a focal laryngeal dystonia, paralleling the work of Marsden et al (10). In later reports, Schaefer (16) and Ludlow (17) also showed with EMG evidence that this disorder, like other dystonias, is a disorder of motor control. Recently, structural alterations in brain organization were demonstrated in patients with LD, including focal reduction of axonal density and myelin along the corticobulbar/corticospinal tract that sends motocortical output to the brainstem phonatory motoneurons. (18). We therefore believe that the more appropriate nomenclature for these disorders should be laryngeal dystonia, with multiple phenomenological presentations. We will use this term in the remainder of this paper.

Review of our studies

Over the last 33 years, we have clinically diagnosed over 1400 patients with laryngeal dystonia (LD) over the past 33 years. These patients had all of their demographic and medical history recorded as well as clinical and endoscopic evaluation of their phenomenological presentations reviewed. In the review that follows, subsets of this broader cohort are discussed in the context of the individual studies.

Phenomenology

Among the 1400 patients, 63% were female, 82% had adductor symptoms and 17% had abductor symptoms. Typically, abductor patients are reported to make up about 10% of LD cases, however our higher numbers are most likely due to referral bias (19).

Our review of these patients also revealed other variants including mixed adductor and abductor types during speech (n=6), singer’s dystonia (n=7), adductor respiratory dystonia (n=14) and patients with dystonic tremor (25%). In general, dystonic tremors can be rapid and irregular and repetitive, with a directional preponderance. The LD tremor may be a posturing of the adductor and abductor muscles with a agonist-antagonist co-contraction tremor (20,21,22,23).

Many dystonic patients display a “geste antagoniste” or a sensory trick, which can ameliorate the dystonic movements. In LD it can be touching the nares, pressing the hand to the back of head or abdomen, pulling on the ear, pressing above the sternal notch or humming or laughing before speaking. Some use a false accent. Over 55% of patients also improve with alcohol intake (24), or muscle relaxants (e.g., benzodiazepines, baclofen) and may worsen under stress or speaking on the telephone. Emotional phonation for laughing or crying was normal. About 25% had an irregular “dystonic” vocal tremor on phonation (perhaps a tremor related to isometric agonist/antagonist contraction). There was no laryngeal tremor visualized for any other active laryngeal activity.

Our series showed a positive family history for dystonia in 12% of the group. Most of the group with laryngeal dystonia remained focal (82.4%), while 12.3% later developed other cranial manifestations, and 5.3% developed extracranial manifestations (20, 25).

Adductor LD

When the Adductor group was evaluated, a cross-sectional sample of 60 consecutive subjects with ADLD was assessed with voice-related questionnaires, vocal tasks and blinded clinician evaluation. Voice samples were recorded as the subjects read the Rainbow Passage aloud, described the Cookie Theft picture, sang “Happy Birthday,” and counted from 80 to 89. Two laryngologists and two speech-language-pathologists reviewed the recordings to identify and rate the severity of the voice symptoms on the Unified Spasmodic Dysphonia Rating Scale (USDRS).13 During the review of the reading Rainbow Passage, all clinicians identified and timed the duration of voice arrests as momentary (< 1 second), short (1–2 seconds), or long (>2 seconds in duration). (26) The average age in this series was 61.3 years with a mean duration of the disorder of 16.1 years. The average age of onset was 48 years. The mean Voice Handicap Index-10 (VHI-10) score as 21.3 and the mean Unified Spasmodic Dysphonia Rating Scale (USDRS) overall symptom severity score was 4.0 (+/−1.0). The VHI-10 ratings were recent scores. The most frequent and severe symptoms identified by both subjects and clinicians were roughness (82%), strain/strangle (80%), and increased expiratory effort (64%). Abrupt voice initiation (5%), voice arrest (4%) and aphonia (0%) were rare. Patients rated vocal symptoms as significantly more severe at initial diagnosis than at the time of the evaluation due to their treatment with Botulinum toxin (p<0.0001). Of the patients who had voice arrests (N=21- 38.2%) 71.4% had 2 or fewer arrests and 5 (23.8%) had 3 or more arrests. There was uniform agreement amongst all four clinicians regarding the presence or absence of voicing arrests for only 10 subjects (18.2%). Therefore we concluded, in contrast to other groups, that counting only the number of breaks in LD patients was a poor tool for diagnosis (26).

All of the 1400 patients had flexible laryngoscopic examination with video recording so that the results could later be evaluated. The adductor variety was categorized on a 4 point scale of hyperadduction: Type 1 with vocal fold hyperadduction on connected speech segments at the glottal level; Type 2 with the same findings at the glottal level and also included hyperadduction of the false vocal folds; Type 3 included additional anterior pull of arytenoids toward the epiglottis; and Type 4 had sphincteric closure of the glottis. The abductor patients had clear abduction while attempting to phonate during connected speech segments such as on counting from 60 to 70 or sentences like “Harry’s Happy Hat” or “The Pretty Puppy bit the Tape”. All other laryngeal functions were normal.

In another study, we reviewed 350 patient charts, which revealed 169 charts showed patient who recalled the circumstances surrounding the onset of their symptoms. Forty-five percent were described as sudden onset. The most common factors associated with the sudden onset were stress (42%), upper respiratory infection (33%), and pregnancy and parturition (10%) (27).

Abductor LD

Abductor LD is characterized by breathy breaks or aphonia during speech. This is due to intermittent abduction of the vocal folds during phonation resulting in reduction of loudness or aphonic whispered segments of speech. The vocal folds during unvoiced segments become fixed in opening or delay in closure for voiced segments of speech. Fiberoptic laryngoscopy in these patietns reveal synchronous and untimely abduction of the true vocal folds allowing air escape and minimizing sound production. These spasms are triggered by consonant sounds, particularly when they are in the initial position in words. These patients are usually worse under stress or on the telephone and may have a normal laugh, normal yawn, normal humming and occasionally normal singing. In our center, there are about 230 patients or 17% of the total series who present with Abductor phenomena. This is higher than the roughly 10% in most series due to a referral bias.

Singer’s LD

We also found a small number (seven) of patients who had symptoms only during singing. These were all professional singers and 4 of the 5 were of the adductor type. In two of these patients the symptoms ultimately progressed to also include their speaking activity (28).

Adductor Breathing LD

We identified and described another task specific laryngeal dystonia which involved adductor spasms during inspiration. This caused stridor, but never hypoxia. It didn’t involve speaking, and often disappeared if the breath was preceded with humming or laughing. It never occurred while the patient was asleep. (29)

Mixed Adductor/Abductor LD

Seven of our 1400 patient group switched over time from Adductor to Abductor or vice versa and 6 who were truly mixed Adductor/Abductor. This observation may be consistent with Cannito’s 1981 notion (30) that all patients are mixed with and Adductor or Abductor predominance.

The abnormal phenomena in functionally specific dystonic processes, seem not only to be related to muscular response to an abnormal efferent signal, but also abnormal processing of afferent or sensory signals. The muscle spindle fibers are most commonly seen in the interarytenoid muscle, but are sparse in the other laryngeal muscle. (31) Most of the sensory feedback seems, from recent studies, to be from mucosal deflection mechanoreceptors. Phonation causes repeated mechanical pertubation to the vocal folds and central suppression likely plays a role in facilitating fluidity of sound production during vocalization and speech by controlling the adductor reflex responses (20, 32).

Modification of phenomena with local injections of botulinum toxin

To manage the symptoms of LD, in April of 1984, we treated the first LD patient with Botulinum toxin injection of laryngeal muscles with success. (33,34) The start and establishment of this treatment in LD was a natural progression in the field, utilizing techniques and botulinum toxin type A (Oculinum) developed by Dr. Allen Scott for the management of strabismus and blepharospasm (a dystonia affecting eyelid closure) (35,36). Since that first injection, we have treated over 1400 patients (near 25,000 injections) and have developed dosing patterns that in our clinic maximize the therapeutic benefit for symptom control (37,38).

Biological effect of Botulinum toxin

After injection the toxin is internalized into nerve endings. The neurotoxin light chain is translocated across the vesicular membrane into the cytosol via a process involving the heavy chain (39). The light chain functions as a zinc-dependent endopeptidase that cleaves one or more proteins necessary for vesicular neurotransmitter release (40). Each botulinum toxin serotype cleaves at least one peptide bond on a SNARE protein (soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor) (41), which make up the vesicle docking and fusion apparatus required for neurotransmitter exocytosis. Botulinum toxin types A, C1, and E cleave SNAP-25 (synaptosomal membrane-associated protein 25 kD), whereas types B, D, F, and G cleave the vesicle associated membrane proteins (VAMPs; synaptobrevins) (39). Serotype C1 also cleaves syntaxin (42, 43).

Clinical effect of Botulinum toxin

The clinical effects of botulinum neurotoxins last approximately 3–4 months on average and re-injection is typically required to maintain clinical benefits. Botulinum neurotoxins not only inhibit acetylcholine release from alpha motor neuron terminals, but also from gamma motor neurons (44, 45). This action has been found to reduce the muscle spindle inflow to alpha motoneurons, which may alter reflex muscular tone (44). The well-known action-induced, task-specific nature of LD suggests that indeed, afferent feedback may play a role in it’s pathophysiology. Further, the phenomenon of the sensory trick suggests that the alteration of afferent signals may be therapeutically useful. Over time, the sensory trick generally loses its effectiveness. The reason for this is not known, but it appears that the central nervous system eventually overcome this change in input by returning to the uncompensated state of sending inappropriate signals to involved muscles. This may explain why interventions have been largely unable to control symptoms permanently in various dystonias. In the case of LD, although recurrent nerve section, anterior commissure release and other surgical measures have all produced encouraging short term-results, long-term benefit has proved difficult to achieve in many patients, as the abnormal central programming seems to “defeat” the surgical treatment (31).

The broad success of botulinum toxin as a treatment for focal dystonias, laryngeal dystonia among them, may be due to the specificity, repeatability and reversibility of the chemodenervation. Nerve terminal recovery from chemodenervation is a continuous, multi-phase process, beginning shortly after acetylcholine release is blocked in preclinical models (46). The cycle of recovery and reinjection with botulinum toxin may make it impossible for the central nervous system to “defeat” the denervation, such as may occur in a permanent treatment, because it never reaches a stable plateau. That voice benefit from injection sometimes extends beyond that expected from the observed in vitro activity of botulinum toxin and suggests that its clinical effect may be due to more than simple acetylcholine blockade at the neuromuscular junction. Some authors have hypothesized that botulinum toxin may affect neurotransmission in the afferent system as well. In fact, there is evidence that in dystonia, botulinum toxin has a transiently functional effect on the mapping of muscle representation areas in the motor cortex, with reorganization of inhibitory and excitatory intracortical pathways, probably through peripheral mechanisms (47, 48). In LD, changes in muscle activation are observed in both injected and non-injected muscles, however functional MRI provided contradictory results showing both alleviation and the lack of any effects on abnormal brain activation (49, 50, 51).

Dosing Regime

The use of botulinum toxin has been reviewed by professional societies since 1990 and we have continued to treat patients off-label in our clinics (52, 53, 54, 55). Our injections are based on a standard dilution of 4.0mL of preservative-free saline/100U vial of onabotulinumtoxin A (Botox®) for the larynx, diluting the solution further in the syringe as needed for each patient. The effective dose is not proportional to body mass or dysphonia severity, and varies considerably. Because injecting a large quantity of fluid into the vocal folds may cause dyspnea, we try to limit the volume of each injection to 0.1mL. The injections are given under EMG control for accurate placement near motor endplates.

Botulinum toxin in Adductor LD

The symptoms for this disorder tend to wax and wane, and have modifiers such as stress. Therefore the doses and specific treatment paradigm are often adjusted at each visit based on current symptoms.

For adductor LD, our initial dose is approximately 1unit per side, which represents a low average dose for our patient population. All dosing reported in this paper are dosing units related to onabotulinumtoxinA units. In a recent publication, we did find a gender difference. In a study of 201 patients we found that females had an average dose per vocal fold of 1.3 units +/− 1.1 and males 0.6 units +/− 0.42. (56) Some patients do not tolerate bilateral injections due to experiencing excessive breathiness or aspiration of fluids, and we empirically found unilateral injections of an average of 1.5 units or less and alternating sides have more consistent voicing, but usually a shorter duration of symptom control. Some patients need bilateral injection but can not tolerate the initial weak voice and we stagger the injection sides two or more weeks apart. We also have a small number of patients who receive more frequent mini dose injections as low as 0.01 units per side. For patients who displayed severe supraglottic squeeze with connected speech segments, we reported a technique of injecting the supraglottic musculature with EMG guidance and fiberoptic visualization (57). A very few of our patients needed additional treatment of the interarytenoid muscle, especially those with significant dystonic tremor (58.) Since we are treating symptom, not disease, with botulinum toxin injections, we found the best results with individualizing the treatment for each patient. With these patient and visit-specific considerations in a prospective study of 100 patients, we found 2 response curves. One had a few days of breathy voice followed by an increased percentage function which maintains for 3–4 months. The second group had no voice loss, but a consistent improvement over several days until the peak at >90% was reached and maintained for 3–4 months (59) We may add a small dose a few weeks after the initial one if the voice does not become fluent. In the great majority of patients, dysphonia is well-controlled for 3 months or more with injections of 0.625U to 2.5U to each side (1.25 to 5 units total dose). Using these techniques we found the average onset of action of 2.4 days and a peak effect usual at 9 days which maintains for 15.1 weeks average. The average benefit as judge by patients with a validated percent function scale was 91.2% of their normal function. The side effects seen in the adductor LD population were 23% with mild breathiness on speaking, 10% with mild difficulty drinking fluids and <1% with local pain, itching or rash. (60, 61, 62, 63)

We also found that toxin injections could benefit patients who had received a unilateral recurrent nerve section as treatment, however the vocal quality for speech was never as good as those who did not have previous surgery. (64,65). An additional study was done comparing the dose and effects of rimabotulinumtoxinA (Myobloc (R)) to onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox) and found about a 53.1:1 relative dosing comparator, with a faster onset (2.09 days vs. 3.2 days) but a shorter duration with Myobloc (10.8 weeks vs. 17 weeks) (66).

Botulinum toxin in Abductor LD

For abductor spasmodic dysphonia, we initially inject one posterior cricoarytenoid muscle with 3.75U of botulinum toxin, and estimate the contralateral dose after evaluating vocal fold mobility two weeks later. A vocal fold that is completely unable to abduct requires that the other side be treated with a small dose to avoid the inability to abduct on inspiration, whereas a more mobile one permits a larger dose to be used. Asymmetric dosing is the rule in abductor LD. Fluctuations in disease severity in spasmodic dysphonia occasionally may require small adjustments in dose. These injections are given with EMG control either with rotation of the larynx and injecting behind the posterior thyroid lamina, through the pyriform sinus and into the PCA overlying the cricoid or injection through the cricothyroid membrane, traversing the airway and then going through the rostrum of the cricoid to reach the PCA. The former approach is harder in older patients (particularly males) due to increased calcification in the cricoid.

Nearly 20% of the abductors only require unilateral injection for control of symptoms. Due to the potential airway issues, limiting the ability to administer simultaneous bilateral injections, greater than 30% of the abductors are also on low dose oral agents for dystonia. The results in a 225 patient cohort show an average onset of toxin effect at 4.1 days, a peak effect at 10 days, and an average best percent function of 70.3% of normal function. Two percent of our patients had mild wheezing and 6% had transient difficulty swallowing solids (67, 68, 69, 70, 71).

Secondary non-response

Secondary non-response is rare in laryngeal dystonia treatment probably due to the small doses used and therefore a reduced antigenic challenge. We have 6 of 1400 primary laryngeal dystonia patients who have become secondary non-responders. They were then switched to rimabotulinumtoxinB (Myobloc ®) for a year and then were challenged again with onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox ®) and all but one responded. One failed, but was challenged with incobotulinumtoxinA (Xeomin ®) and she is still responding for greater than 1 year (72). She may have antibody to accessory proteins rather than the toxin itself.

Genetic Studies

During the last 20 years several genes for various forms of dystonia have been discovered (73,74). (see Table 2) Although only 12% of our laryngeal dystonia population had a positive family history of dystonia, we undertook genetic studies to assess the role of these genes in our patient population. Indeed, in one of our early studies, the proband presented with laryngeal dystonia (75).

Table 2.

Dystonia Associated Genes

| Symbol | Gene | Locus | Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| +*DYT1 | TOR1A | 9q34 | early-onset torsion dystonia |

| *DYT2 | HPCA | 1p35 | autosomal recessive primary isolated dystonia |

| DYT3 | TAF1 | Xq13 | X-linked dystonia- parkinsonism |

| +*DYT4 | TUBB4 | 19p13 | autosomal dominant Whispering dysphonia |

| DYT5a | GCH1 | 14q22 | autosomal dominant dopamine-responsive dystonia |

| DYT5b | TH | 11p15 | autosomal recessive dopamine-responsive dystonia |

| +*DYT6 | THAP1 | 8p11 | autosomal dominant dystonia with cranial-cervical predilection |

| *DYT7 | ??? | 18p | autosomal dominant primary focal cervical dystonia |

| DYT8 | MR1 | 2q35 | paroxysmal nonkinesiogenic dyskinesia |

| DYT9 | SLC2A1 | 1p35 | episodic choreoathetosis/spasticity (same as DYT18) |

| DYT10 | PRRT2 | 18p11 | paroxysmal kinesiogenic dyskinsia |

| DYT11 | SGCE | 7q21 | myoclonic dystonia |

| DYT12 | ATP1A3 | 19q12q13 | rapid onset dystonia and parkinsonism and alternating hemiplegia of childhood |

| *DYT13 | ???? | 1P36 | autosomal dominant cranio-cervical/upper limb dystonia- in one Italian family |

| DYT15 | ??? | 18p11 | myoclonic dystonia |

| DYT16 | PRKRA | 2q31 | autosomal recessive young onset dystonia/parkinsonism |

| *DYT17 | ??? | 20p11 | autosomal recessive dystonia in one family |

| DYT18 | SLC2A1 | 1p35 | paaroxysmal exercise induced dyskinesia |

| DYT19 | PRRT2 | 16q13 | episodic kinesiogenic dyskinesia 2 |

| DYT20 | ??? | 2q31 | paroxysmal Non-kinesiogenic dyskinesia |

| DYT21 | ??? | 2q14 | late-onset torsion dystonia |

| *DYT23 | CIZ1 | 9q34 | adult onset cervical dystonia |

| *DYT24 | ANO3 | 11p14 | autosomal dominant |

| cranio-cervical dystonia with prominent tremor | |||

| +*DYT25 | GNAL | 18p11 | adult onset focal dystonia |

Isolated Dystonia Genes

genes associated with Laryngeal Dystonia

Some of our patients were included in collaborative studies with Dr. Mark LeDoux (University of Tennessee). Using various subsets of our patient samples, he found no mutations in the TOR1A gene (76) or the TUBB4A gene (77) but did identify novel THAP1 mutations in LD patients (78) as well as an association with a rare intronic variant in THAP1 across various focal dystonias including LD (3 cervical dystonia; 3 laryngeal dystonia; 1 oromandibular dystonia; 2 blepharospasm; and 3 unclassified).

Our group also looked for mutations in TOR1A, TUBB4A, THAP1, and GNAL in 57 LD patients undergoing imaging studies. A single patient with adductor LD was identified with a GNAL mutation showing for the first time that mutations in GNAL may represent a causative genetic factor in isolated LD (79). Exploratory evidence of distinct neural abnormalities in the GNAL carrier compared to sporadic and familial LD cases without known genetic mutations may suggest a divergent pathophysiological cascade underlying this disorder. Specifically, the GNAL carrier had increased activity in the fronto-parietal cortex and decreased activity in the cerebellum when compared to 26 patients without the mutation (79) The GNAL mutation mapped in some patients with LD seems to be associated with dysregulation of dopamine metabolism in the striatum producing dystonic symptoms (80).

Ultrasound and Functional Brain Imaging Studies

In collaboration the Dr. Uwe Walter and colleagues at the University of Rostock, Germany we studied 14 patients with adductor LD (10 female; 4 male) with age and gender matched controls using sonography of the brain. We found lenticular nuclear and caudate nuclear hyperechogeneity in 12 of the patients and only 1 control. This hyperechogeneity is also found in other forms of dystonia. Based on a few autopsy specimens, the hyperechogeneity might be related to small amounts of mineral deposition (81, 82, 83, 84).

With the advent of functional brain imaging, much has been learned about normal and abnormal brain function during speaking. Over the past several years, we have studied the variations in laryngeal dystonic phenomenology, their genetic profiles and functional brain patterns to try to better understand the abnormalities producing the poor vocal function (85).

The topology, as well as global and local features of large-scale brain networks, were studied across different focal task-specific and non-task-specific dystonias and findings were compared to healthy normal controls. The dystonic patients showed altered network architecture with abnormal expansion or shrinkage of neural communities, such as breakdown of basal ganglia-cerebellar community, loss of pivotal region of the information transfer hub in the premotor cortex, and pronounced connectivity reduction within the sensorimotor and frontoparietal regions. This suggests that isolated focal dystonias represent a disorder of large-scale functional networks. Distinct symptoms may be linked to disorder-specific network aberrations (85,86,87,88).

A study of patients with a clinical diagnosis of ADLD and ABLD was performed evaluating the neural correlates of abnormal sensory discrimination in these individuals. Based on the clinical phenotype, the adductor form-specific correlations were observed in the frontal cortex, whereas the abductor form-specific correlations were in the cerebellum and putamen. These studies suggest the presence of potentially divergent pathophysiological pathways underlying the different manifestations of this disorder (89).

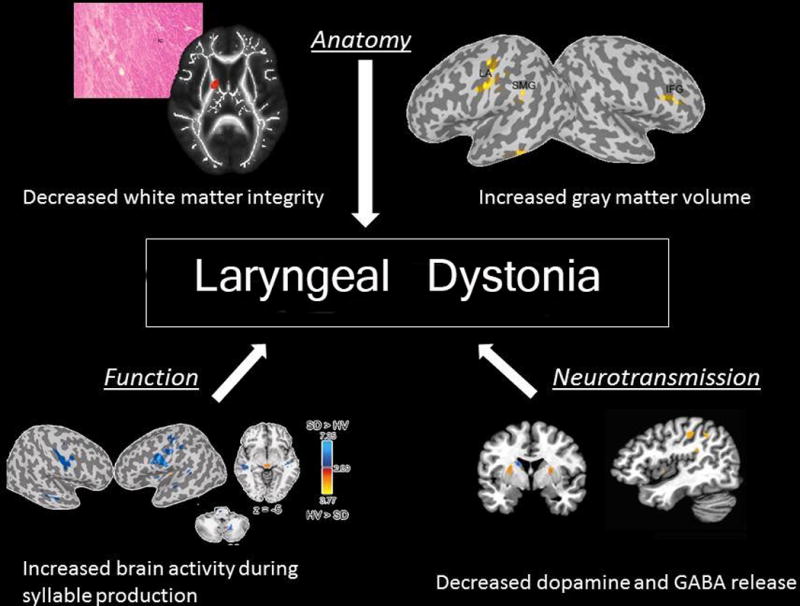

A study of LD with and without tremor was performed to define dystonic tremor pathophysiology. This was done with fMRI, voxel-based morphometry and diffusion-weighted imaging. When compared to controls, LD patients with and without tremor showed increased activation in the sensorimotor cortex, inferior frontal and superior temporal gyri, putamen and ventral thalamus, as well as deficient activation in the inferior parietal cortex and middle frontal gyrus (MFG). Direct patient group comparisons showed that LD with tremor had additional abnormalities in MFG and cerebellar function and white matter integrity in the posterior limb of the internal capsule. Onset in LD patients with and without tremor was associated with right putaminal volumetric change. These are heterogenous disorders with the same pathophysiological spectrum each carrying a characteristic neural signature which may help to establish differential markers (90). (see Fig.1)

Fig 1.

Diagram showing CNS and network changes associated with Laryngeal Dystonia

From our study group, during the past several years, we recruited 98 patients who were grouped based on clinical phenotype (adductor or abductor) and underlying putative genotype (sporadic and familial). Their data on brain activity were submitted to independent component analysis and linear discriminant analysis to investigate brain organization differences and to characterize neural markers for genotype/phenotype categorization. (89) We showed abnormal functional connectivity within the sensorimotor and frontoparietal networks of LD patients compared to normals, which provide a 71% accuracy in characterizing LD from normal subjects, an 81% accuracy in separating sporadic and familial LD, and 71% accuracy in discriminating adductor from abductor LD forms, based on their neural abnormalities (90). This study laid the first foundation for the development of objective neural biomarkers of LD, which can potentially be translated into clinical practice for accurate and unbiased diagnosis of this disorder as well as its several subtypes.

Alcohol Responsiveness and Sodium Oxabate

A number of patients with alcohol responsive LD have been described.. A total of 406 LD patient records from the National Spasmodic Dysphonia Association patient registry were studied. Among these, 76.5% had pure laryngeal dystonia and 23.5 had LD+voice tremor. Based on patient reports, a total of 55.9% of LD were alcohol responsive whereas 58.4% of the LD+ voice tremor were alcohol responsive. This group was segregated since tremor patients alone can be alcohol responsive. The effects of alcohol on the patient reported symptoms in both groups lasted 1–3 hours. It is thought that alcohol may modulate the pathophysiologic mechanisms underlying abnormal neurotransmission of GABA (γ-aminobutyric acid)in dystonia. This may open new pathways for novel therapeutic options (24, 91).

Based on the above study, we conducted an open-label study using (sodium oxabate (Xyrem ®) which has the therapeutic effects on LD symptoms similar to those of ethanol. A total of 53 patients were recruited. Thirty had LD and 23 had LD with voice tremor. In the combined group, the drug had a significant effect on the vocal symptoms observed 30–45 minutes after taking 1.5 gms of drug and lasted an average of 3.5 hours gradually wearing off by 5 hours. All patients tolerated the drug without major side effects. In contrast to botulinum toxin, sodium oxabate had similar effects in the adductor and abductor groups (92). The drug is known to convert into GABA within the brain and increases the dopamine level mediated by GABA receptors (92, 93).

Conclusions

Continuous studies of Laryngeal Dystonia patients over 33 years have led to an improved understanding of the phenomenological characteristics of the neurological disorder. Genetic, therapeutic and fMRI studies have provided new insights into the disorder and new clues to a possibility of objective, rather than subjective diagnoses which may lead to new therapeutic approaches. The data acquired may also lead to future clinical trials to better understand the pathophysiologic differences in the subgroups of LD which may be relevant to more specific diagnosis, treatment options, and information for genetic counseling.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by Grants:

NIH-RO1DC01805

NIH-RO1DC012545

Dystonia Research Foundation

Financial Disclosure: Research Grants from Allergan, Inc and Merz Pharmaceuticals

Footnotes

No Conflicts of Interest

This paper was presented at the American Laryngological Association Meeting, San Diego, CA, April 26, 2017

References

- 1.Traube L. Gesammelte Beitrage zur Pathologie und Physiologie. 2. Verlag von August Hirschwald; Berlin: 1871. pp. 674–678. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schnitzler J, Hajek M, Schnitzler A. Nebst Anleitung zur Diagnose und Therapie der Krankheiten des Kehlkopfes und der Luftrohre. Wilhelm Braumuller; Wien und Leipzig: 1895. Klinischer Atlas der Laryngologie; pp. 215–224. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fraenkel B. Ueber Beschaeftigungsneurosen der Stimme. G Thieme; Leipzig: 1887a. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fraenkel B. Ueber die Beschaeftigungsschwaeche der Stimme: mogiphonie. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1887b;13:121–123. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gowers WR. Manual of Diseases of the Nervous System. 3. Churchill; London: 1899. p. 200. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Critchley M. Spastic dysphonia (“inspiratory speech”) Brain. 1939;62:96–103. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bellussi G. Le Disfonie Impercinetiche. Atti Labor Fonet Univ Padova. 1952;3:1. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aronson AE, Brown JR, Litin EM, Pearson JS. Spastic dysphonia. II. Comparison with essential (voice) tremor and other neurologic and psychogenic dysphonias. J Speech Hear Disord. 1968;33:219–231. doi: 10.1044/jshd.3303.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacome DE, Yanez GE. Spastic dysphonia and Meige disease [letter] Neurology. 1980;30:340. doi: 10.1212/wnl.30.4.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marsden CD, Sheehy MP. Spastic dysphonia, Meige disease, and tortion dystonia [letter] Neurology. 1982;32:1202–03. doi: 10.1212/wnl.32.10.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blitzer A, Lovelace RE, Brin MF, Fahn S, Fink ME. Electromyographic findings in focal laryngeal dystonia (spastic dysphonia) Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1985;94(6 pt1):591–94. doi: 10.1177/000348948509400614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.BLITZER A. Electromyographic Findings in Spasmodic Dysphonia. In: Gates GA, editor. Symposium on Spastic Dysphonia: State of the Art 1984. New York: Voice Foundation; 1985. pp. 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aronson AE. Clinical Voice Disorders. Thieme; New York: 1985. pp. 52–58. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brin MF, Blitzer A, Velicovic M. Movement Disorders of the Larynx. In: BLITZER A, Brin MF, Ramig LO, editors. Neurological Disorders of the Larynx. 2. NY: Thieme Med. Publ.; p. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Albanese A, Bhatia K, Bressman SB, Delong MR, Fahn S, Fung VS, Hallett M, Jankovic J, Jinnah HA, Klein C, Lang AE, Mink JW, Teller JK. Phenomenology and classification of dystonia: a consensus update. Mov Disord. 2013 Jun;28(7):15. 863–73. doi: 10.1002/mds.25475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schaefer S, Watson B, Freeman F, Kondraske G, Pool K, Close L, Finitzo T. Vocal tract electromyographic abnormalities in spasmodic dysphonia preliminary report. Trans Am Laryngol Assoc. 1987;108:187–196. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ludlow CL, Hallett M, Sedory SE, Fujita M, Naunton RF. The pathophysiology of spasmodic dysphonia and its modification by botulinum toxin. In: Berardelli A, Benecke R, Manfredi M, Marsden CM, editors. Motor Disturbances II. Academic Press; New York: 1990. pp. 273–288. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simonyan K, Berman BD, Herscovitch P, Hallett M. Abnormal Striatal Dopinergic Neurotransmission during rest and task production in spasmodic dysphonia. The J of Neuroscience. 2013;33(37):14705–14714. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0407-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel AB, Bansberg SF, Adler CH, Lott DG, Crujido L. The Mayo Clinic Arizona Spasmodic Dysphonia Experience: A Demographic Analysis of 718 Patients. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2015;124(11):859–865. doi: 10.1177/0003489415588557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blitzer A, Brin MF, Stewart CF. Botulinum toxin management of spasmodic dysphonia (laryngeal dystonia): a 12-year experience in more than 900 patients. Laryngoscope. 1998;108(10):1435–41. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199810000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blitzer A. Spasmodic Dysphonia and botulinum toxin: experience from the largest treatment series. European J Neurology. 2010;17(suppl 1):28–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.BLITZER A, Brin MF, Fahn S, Lovelace RE. Clinical and Laboratory Characteristics of Laryngeal Dystonia: A study of 110 cases. Laryngoscope. 1988;98:636–40. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198806000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brin MF, BLITZER A, Fahn S, Lovelace RE. Laryngea Dystonia (LD) at the Dystonia Clinical Research Center (DCRC): Clinical and Electromyographic Features in 110 cases. Neurology (Suppl.1) 1988;129 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kirke DN, Frucht SJ, Simonyan K. Alcohol responsiveness in laryngeal dystonia: a survey study. J Neurol. 2015;262(6):1548–1556. doi: 10.1007/s00415-015-7751-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Leon D, Brin MF, BLITZER A, Heiman G, Fahn S. Genetic factors in spastic dysphonia. Neurology. 1990;40(suppl. 1):142. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stewart CF, Allen EL, Tureen P, Diamond BE, BLITZER A, Brin MF. Adductor Spasmodic Dysphonia: Standard Evaluation of Symptoms and Severity. J Voice. 1997;11:95–103. doi: 10.1016/s0892-1997(97)80029-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Childs L, Rickert S, Murry T, BLITZER A, Sulica L. Patient Perceptions of Factors Leading to Spasmodic Dysphonia: A Combined Clinical Experience of 350 Patients. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:2195–2198. doi: 10.1002/lary.22168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chitkara A, Meyer TK, Keidar A, Blitzer A. Singer’s Dystonia: First Report of a Variant of Spasmodic Dysphonia. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2006 Feb;115(2):89–92. doi: 10.1177/000348940611500201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brin MF, BLITZER A, Heiman G, Fahn S. Treatment of Adductor Breathing Dystonia with Botulinum toxin. Laryngoscope. 1994;104:30–33. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199401000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cannito MP, Johnson P. Spastic Dysphonia: a continuum disorder. J Comm Disord. 1981;14:215–223. doi: 10.1016/0021-9924(81)90037-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mor N, Simonyan K, Blitzer A. Central Voice Production and Pathophysiology of Spasmodic Dysphonia. Laryngoscope. doi: 10.1002/lary.26655. (In Press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhabu P, Poletto C, Mann E, Bielamowicz S, Ludlow CL. Thyroayrtenoid muscle responses to air pressure stimulation of the laryngeal mucosa in human. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2003;112:834–840. doi: 10.1177/000348940311201002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.BLITZER A, Brin MF, Fahn S, Lange D, Lovelace RE. Botulinum toxin (BOTOX) for the treatment of “spastic dysphonia” as part of a trial of toxin injections for the treatment of other cranial dystonias. Laryngoscope. 1986;96(11):1300–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.BLITZER A, Brin M, Fahn S, Lovelace RE. The Use of Botulinum Toxin in the Treatment of Focal Laryngeal Dystonia (Spastic Dysphonia) Laryngoscope. 1988;98:193–97. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198802000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scott AG. Botulinum toxin injection of eye muscles to correct strabismus. Trans Am Ophthal Soc. 1981;79:734–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brin MF, Blitzer A. History of onabotulinumtoxinA therapeutic. In: Carruther A, Carruthers J, Dover JS, Alam M, editors. Botulinum Toxin. 3rd. London: Saunders Elsevier; 2013. pp. 6–12. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sulica L, Blitzer A. Botulinum toxin Treatment of Spasmodic Dysphonia and Other Laryngeal Disorders. In: BLITZER A, Brin MF, Ramig LO, editors. Neurological Disorders of the Larynx. 2nd. NY: Thieme Med. Publ.; p. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brin MF, BLITZER A, Stewart C, Fahn S. Treatment of Spasmodic Dysphonia (laryngeal dystonia) with injections of Botulinum toxin: review and technical aspects. In: Blitzer A, Brin MF, Sasaki CT, Fahn S, Harris K, editors. Neurological Disorders of the Larynx. NY: Thieme Medical Pub. Inc.; 1992. pp. 214–229. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoch DH, Romero-Mira M, Ehrlich BE, Finkelstein A, DasGupta BR, Simpson LL. Channels formed by botulinum, tetanus, and diphtheria toxins in planar lipid bilayers: relevance to translocation of proteins across membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82(6):1692–1696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.6.1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schiavo G, Rossetto O, Benfenati F, Poulain B, Montecucco C. Tetanus and botulinum neurotoxins are zinc proteases specific for components of the neuroexocytosis apparatus. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;710:65–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb26614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pellizzari R, Rossetto O, Schiavo G, et al. Tetanus and botulinum neurotoxins: mechanism of action and therapeutic uses. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1999;354(1381):259–268. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1999.0377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lalli G, Herreros J, Osborne SL, Montecucco C, Rossetto O, Schiavo G. Functional characterisation of tetanus and botulinum neurotoxins binding domains. J Cell Sci. 1999;112(Pt 16):2715–2724. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.16.2715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blasi J, Chapman ER, Yamasaki S, Binz T, Niemann H, Jahn R. Botulinum neurotoxin C1 blocks neurotransmitter release by means of cleaving HPC-1/syntaxin. EMBO J. 1993;12(12):4821–4828. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06171.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Filippi GM, Errico P, Santarelli R, Bagolini B, Manni E. Botulinum A toxin effects on rat jaw muscle spindles. Acta Otolaryngol. 1993;113(3):400–404. doi: 10.3109/00016489309135834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosales RL, Arimura K, Takenaga S, et al. Extrafusal and intrafusal muscle effects in experimental botulinum toxin -A injection. Muscle Nerve. 1996;19:488–496. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4598(199604)19:4<488::AID-MUS9>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.de Paiva A, Meunier FA, Molgo J, Aoki KR, Dolly JO. Functional repair of motor endplates after botulinum neurotoxin type A poisoning: biphasic switch of synaptic activity between nerve sprouts and their parent terminals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(6):3200–3205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Byrnes ML, Thickbroom GW, Wilson SA, et al. The corticomotor representation of upper limb muscles in writer’s cramp and changes following botulinum toxin injection. Brain. 1998;121:977–988. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.5.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gilio F, Curra A, Lorenzano C, Modugno N, Manfredi M, Berardelli A. Effects of botulinum toxin type A on intracortical inhibition in patients with dystonia. Ann Neurol. 2000;48:20–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bielamowicz S, Ludlow CL. Effects of botulinum toxin on pathophysiology in spasmodic dysphonia. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2000;109:194–203. doi: 10.1177/000348940010900215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ali SO, Thomassen M, Schulz GM, et al. Alterations in CNS activity induced by botulinum toxin treatment in spasmodic dysphonia: an H215O PET study. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2006;49(5):1127–1146. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2006/081). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haslinger B, Erhard P, Dresel C, Castrop F, Roettinger M, Ceballos-Baumann AO. Silent event-relatedfMRI reveals reduced sensorimotor activation in laryngeal dystonia. Neurology. 2005;65(10):1562–1569. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000184478.59063.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.American Academy of Neurology. Assessment: The clinical usefulness of botulinum toxin‐A in treating neurological disorders; Report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee Committee of the American Academy of Neurology. (MF Brin, Facilitator of report) Neurology. 1990;40:1332–1336. doi: 10.1212/wnl.40.9.1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.American Academy of Otolaryngology‐Head and Neck Surgery. Academy policy statement: Botox for spasmodic dysphonia. AAO‐HNS Bulletin. 1990;9:8. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Clinical use of botulinum toxin. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement, November 12–14, 1990. Arch Neurol. 1991 Dec;48(12):1294–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Simpson DM, Blitzer A, Brashear A, Comella C, Dubinsky R, Hallett M, Jankovic J, Karp B, Ludlow CL, Miyasaki JM, Naumann M, So Y. Assessment: Botulinun neurotoxin for the treatment of movement disorders (an evidence-based review): Report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2008;70:1699–1706. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000311389.26145.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lerner MZ, Lerner BA, Patel AA, BLITZER A. Gender Differences in Onabotulinum Toxin A dosing for Adductor Spasmodic Dysphonia. Laryngoscope. 2017 May;127(5):1131–1134. doi: 10.1002/lary.26265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Young N, BLITZER A. Management of supraglottic squeeze in adductor spasmodic dysphoniua: a new technique. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:2082–4. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e318124a97b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Klotz DA, Maronian NC, Waugh DF, Shahinfar A, Robinson L, Hillel AD. Findings of multiple muscle involvement in a study of 214 patients with laryngeal dystonia using fine-wire electromyography. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2004;113(8):602–12. doi: 10.1177/000348940411300802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Novakovic D, Waters HH, D’Elia JB, BLITZER A. Botulinum toxin treatment of adductor spasmodic dysphonia: longitudinal functional outcomes. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:606–12. doi: 10.1002/lary.21395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.BLITZER A, Brin MF. Laryngeal Dystonia: A series with Botulinum Toxin Therapy. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1991;100:85–90. doi: 10.1177/000348949110000201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brin MF, BLITZER A, Fahn S, Lovelace RE. Adductor Laryngeal Dystonia: treatment with local injections of botulinum toxin (BOTOX) Neurology (Suppl.1) 1988;244 doi: 10.1002/mds.870040401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brin MF, BLITZER A, Fahn S, Gould W, Lovelace RE. Adductor Laryngeal Dystonia (Spastic Dysphonia): Treatment with Local Injections of Botulinum Toxin (BOTOX) Movement Disorders. 1989;4:287–296. doi: 10.1002/mds.870040401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tang CG, Novakovic D, Mor N, BLITZER A. Onabotulinum toxin A dosage trends over time for adductor spasmodic dysphonia: A 15-year Experience. Laryngoscope. 2016;126:678–681. doi: 10.1002/lary.25551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sulica L, BLITZER A, Brin MF, Stewart CF. Botulinum Toxin Management of Adductor Spasmodic Dysphonia after Failed Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve Section. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2003;112:499–505. doi: 10.1177/000348940311200603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.BLITZER A, Brin MF, Fahn S. Botulinum Toxin Therapy for Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve Section failure for Adductor Laryngeal Dystonia. Trans Am Laryngol Assoc. 1989;110:206. (abstr.) [Google Scholar]

- 66.BLITZER A. Botulinum toxin A and B: A Comparative Dosing Study for Spasmodic Dysphonia. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;133:836–838. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.BLITZER A, Brin MF, Stewart C, Fahn S. Abductor Laryngeal Dystonia: A series treated with Botulinum toxin. Laryngoscope. 1992;102:163–167. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199202000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brin MF, BLITZER A, Stewart C, Fahn S. Botulinum toxin: Now for abductor laryngeal dystonia. Neurology. 40381(suppl. 1):1990. [Google Scholar]

- 69.BLITZER A, Stewart C. Voice Disorders. St. Louis: C.V. Mosby; 1992. Evaluation and Management of Abductor Spasmodic Dysphonia with Botulinum Toxin; pp. 147–155. Stemple ed. [Google Scholar]

- 70.BLITZER A, Brin MF. Botulinum toxin in the Management of Adductor and Abductor Spasmodic Dysphonia. Operative Techniques in Otolaryngology/Head and Neck Surgery. 1993;4:199–206. [Google Scholar]

- 71.BLITZER A, Brin MF. Botulinum toxin for Abductor Spasmodic Dysphonia. In: Jankovic J, Hallet M, editors. Therapy with Botulinum Toxin. N.Y.: Marcel Dekker, Inc; 1994. pp. 451–459. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mor N, Tang C, BLITZER A. Botulinum Toxin in Secondarily Non- responsive Patients with Spasmodic Dysphonia. Otolaryn Head Neck Surg. doi: 10.1177/0194599816644708. (In Press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Balint B, Bhatia KP. Isolated and combined dystonia syndromes – an update on new genes and their phenotypes. Eur J Neurol. 2015 Apr;22(4):610–7. doi: 10.1111/ene.12650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ozelius LJ, Hewett SW, Page CE, Bressman SB, Kramer PL, Shalish C, deLeon D, Brin MF, Raymond D, Corey DP, Fahn S, Risch NJ, Buckler AJ, Gusella JF, Breakefield XO. The early-onset torsion dystonia gene (DYT1) encodes an ATP-binding protein. Nat Genet. 1997;17:40–48. doi: 10.1038/ng0997-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Almasy L, Bressman SB, Raymond D, Kramer PL, Greene PE, Heiman GA, Ford B, Yount J, de Leon D, Chouinard S, Saunders-Pullman R, Brin MF, Kapoor RP, Jones AC, Shen H, Fahn S, Risch NJ, Nygaard TG. Idiopathic torsion dystonia linked to chromosome 8 in two Mennonite families. Ann Neurol. 1997;42(4):670–673. doi: 10.1002/ana.410420421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Xiao J, Bastian RW, Perlmutter JS, Racette BA, Tabbal SD, Karmi M, Paniello R, BLITZER A, Batish SD, Wszolek ZK, Uitti RJ, Hedera P, Simon DK, Tarsey D, Troung DD, Frei KP, Pfeiffer RF, Gong S, Zhao Y. LeDoux, MS- “High-throughput Mutational Analysis of TOR1A in Primary Dystonia. BMC Medical Genetics. 2009;11:10–24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-10-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vemula SR, Xiao J, Bastien RE, Momcilivic D, BLITZER A, LeDoux M. PathogenicVariants in TUBB4A are not found in Spasmodic Dysphonia or other Primary Dystonias. Neurology. (pending) [Google Scholar]

- 78.Xiao J, Bastian RW, Perlmutter JS, Racette BA, Tabbal SD, Karimi M, Paniello R, BLITZER A, Batish SD, Wszolek ZK, Uitti RJ, Van Gerpen JA, Hedera P, Simon DK, Tarsey D, Troung DD, Frei KP, Pfeiffer RF, Gong S, LeDoux M. Novel humanpathological mutations. Gene symbol: THAP1. Disease: dystonia 6. Hum Genet. 2010;127:469–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Putzel GG, Fuchs T, Battistella G, Rubien-Thomas E, Frucht SJ, Blitzer A, Ozelius LJ, Simonyan K. GNAL Mutation in Isolated Laryngeal Dystonia. Mov Disord. 2016;31(5):750–5. doi: 10.1002/mds.26502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Simonyan K, Berman BD, Herscovitch P, Hallett M. Abnormal striatal dopaminergic neurotransmission during rest and task production in spasmodic dysphonia. J Neurosci. 2013;33:14705–14714. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0407-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Walter U, Blitzer A, Benecke R, Grossmann A, Dressler D. Sonographic detection of basal ganglia abnormalities in spasmodic dysphonia. European Journal of Neurology. 2014;21:349–52. doi: 10.1111/ene.12151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Walter U, Krolikowski K, Tarnacka B, Benecke R, Czlonkowska A, Dressler D. Sonographic detection of basal ganglia lesions in asymptomatic and symptomatic Wilson’s disease. Neurology. 2005;64:1726–1732. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000161847.46465.B9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Becker G, Berg D, Francis M, Naumann M. Evidence for disturbances of copper metabolism in dystonia. From the image towards a new concept. Neurology. 2001;57:2290–2294. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.12.2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Simonyan K, Tovar-Moll F, Ostuni J, et al. Focal white matter changes in spasmodic dysphonia: combined diffusion tensor imaging and neuropathological study. Brain. 2008;131(Pt 2):447–459. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Defazio G, Berardelli A, Hallett M. Do primary adult-onset focal dystonias share aetiological factors? Brain. 2007;130:1183–1193. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Battistella G, Fuertinger S, Fleysher L, Ozelius LJ, Simonyan K. Cortical sensorimotor alterations classify clinical phenotype and putative genotype of spasmodic dysphonia. European J Neurol. 2016 doi: 10.1111/ene.13067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Simonyan K, Ludlow CL. Abnormal activation of the primary somatosensory cortex in spasmodic dysphonia: an fMRI study. Cereb Cortex. 2010;20:2749–2759. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Delmaire C, Vidailhet M, Elbaz A, Bourdain F, Bleton JP, Sangla S, Meunier S, Terrier A, Lehericy S. Structural abnormalities in the cerebellum and sensorimotor circuit in writer’s cramp. Neurology. 2007;69:376–380. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000266591.49624.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Termsarasab P, Ramdhani RA, Battistella G, Rubien-Thomas E, Choy M, Farwell IM, Velickovic M, Blitzer A, Frucht SJ, Reilly RB, Hutchinson M, Ozelius LJ, Simonyan K. Neural Correlates of abnormal sensory discrimination in laryngeal dystonia. NeuroImage: Clinical. 2016;19:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2015.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kirke DN, Battistella G, Kumr V, Rubien-Thomas E, Choy M, Rumbach A, Simonyan K. Neural correlates of dystonic tremor: a multimodal study of voice tremor in spasmodic dysphonia. Brain Imaging Behav. 2016 Feb 3; doi: 10.1007/s11682-016-9513-x. [e publ ahead of printing] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Simonyan K, Frucht SJ. Long-term Effect of Sodium Oxybate (XyremH) in Spasmodic Dysphonia with Vocal Tremor. In: Louis ED, editor. Tremor Other Hyerkinet Mov. Vol. 3. 2013. p. tre-03-206-4731-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rumbach AF, Blitzer A, Frucht SJ, Simonyan K. An open-label study of sodium oxybate (Xyrem) in spasmodic dysphonia. Laryngoscope. 2017 Jun;127(6):1402–1407. doi: 10.1002/lary.26381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Keating GM. Sodium oxybate: a review of its use in alcohol withdrawal syndrome and in the maintenance of abstinence in alcohol dependence. Clin Drug Investig. 2014;34:63–80. doi: 10.1007/s40261-013-0158-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]