Version Changes

Revised. Amendments from Version 1

Version 2 includes formulae used for calculation of CFU in volume of air and CFU in volume of bioaerosol. There is also a clarification about the use of Tween80 and the use of selective antibiotics (PANTA (BD) antibiotic mixture) for the direct agar impaction on the Andersen. The abstract has been amended to clarify the association between cough frequency and production of culturable bioaerosol. Errors in the references has been corrected and appropriate additions have been made.

Abstract

Background: Tuberculosis (TB) is predominantly an airborne disease. However, quantitative and qualitative analysis of bio-aerosols containing the aetiological agent, Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), has proven very challenging. Our objective is to sample bio-aerosols from newly diagnosed TB patients for detection and enumeration of Mtb bacilli.

Methods: We monitored each of 35 newly diagnosed, GeneXpert sputum-positive, TB patients during 1 hour confinement in a custom-built Respiratory Aerosol Sampling Chamber (RASC). The RASC (a small clean-room of 1.4m ) incorporates aerodynamic particle size detection, viable and non-viable sampling devices, real-time CO 2 monitoring, and cough sound-recording. Microbiological culture and droplet digital polymerase chain reaction (ddPCR) were used to detect Mtb in each of the bio-aerosol collection devices.

Results: Mtb was detected in 27/35 (77.1%) of aerosol samples; 15/35 (42.8%) samples were positive by mycobacterial culture and 25/27 (92.96%) were positive by ddPCR. Culturability of collected bacilli was not predicted by radiographic evidence of pulmonary cavitation, sputum smear positivity. A correlation was found between cough rate and culturable bioaerosol. Mtb was detected on all viable cascade impactor stages with a peak at aerosol sizes 2.0-3.5μm. This suggests a median of 0.09 CFU/litre of exhaled air (IQR: 0.07 to 0.3 CFU/l) for the aerosol culture positives and an estimated median concentration of 4.5x10 CFU/ml (IQR: 2.9x10 -5.6x10 ) of exhaled particulate bio-aerosol.

Conclusions: Mtb was identified in bio-aerosols exhaled by the majority of untreated TB patients using the RASC. Molecular detection was more sensitive than mycobacterial culture on solid media, suggesting that further studies are required to determine whether this reflects a significant proportion of differentially detectable bacilli in these samples.

Keywords: respiratory aerosol sampling chamber, bio-aerosol, viable impaction, ddPCR assay, RD9

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) has surpassed HIV/AIDS as a global killer with more than 4000 daily deaths 1. The rate of decline in incidence remains inadequate at a reported 1.5% per annum 1 and it is unlikely that treatment alone will significantly reduce the burden of disease 2. In communities with highly prevalent HIV, Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) genotyping studies have found that recent transmission, rather than reactivation, accounts for the majority (54%) of incident TB cases 3. Therefore, interruption of transmission would likely have a rapid, measurable impact on TB incidence. The physical process of TB transmission remains poorly understood and the application of new technologies to elucidate key events in infectious aerosol production, release, and inhalation, has been slow.

The capacity for airborne transmission of Mtb bacilli was first demonstrated in an elegant series of experiments by Richard Riley and colleagues nearly seventy years ago 4. Venting exhaled air from pulmonary TB patients over a guinea pig facility resulted in infection of the animals leading to the concept of infectious ‘quanta’ (the dose of infectious air required to cause an infection). Notably, these pioneering studies indicated that quanta production was extremely infrequent and definitively attributable to only a small minority of patients. Furthermore, the quantitative relationship between airborne infectious particles and quanta remains unclear.

Empirical studies to characterise airborne infectious particles have been sparse. Two major difficulties plaguing investigation are the purportedly low concentrations of naturally produced Mtb particles, and the complication of environmental and patient-derived bacterial and fungal contamination of airborne samples 5. There have nonetheless been a number of attempts at airborne detection. 6,13.

Of particular interest, a proof of concept study 12 and subsequent feasibility study in Uganda 14 sampled cough-generated aerosols from pulmonary TB patients. Coughing directly into a sampling chamber equipped with two viable cascade impactors resulted in positive cultures from more than a quarter of participants despite their having received 1–6 days of chemotherapy. A follow-up work employing the same apparatus found that participants with higher aerosol bacillary loads could be linked to greater household transmission rates 14 and development of disease 15 findings which suggest that quantitative airborne sampling may serve as a clinical relevant measure of infectivity.

In this study, we aimed to gain further insight into the airborne phase of TB and establish the bacillary concentration in exhaled bio-aerosols. We used the respiratory aerosol sampling chamber (RASC) 16, a novel apparatus designed to optimise patient-derived aerosol sampling, to isolate and accumulate respirable aerosol from a single patient. Environmental sampling detects the Mtb present after a period of ageing in the chamber air. The resulting ‘dried residua’ 17, formed from larger respiratory droplets, are predicted to mimic more closely the putative infectious particle.

Methods

Ethical statement

Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Cape Town Faculty of Health Sciences Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/REF: 680/2013). Written informed consent for publication of the participants details was obtained from the participants. Sampling took place on the same day as treatment initiation with a typical delay of 1–2 hours to complete the study protocol.

Subject recruitment

Participants who had tested positive for drug-sensitive pulmonary TB by GeneXpert were recruited prior to initiation of chemotherapy from a peri-urban township 40km south of Cape Town

Baseline patient data were collected from the clinical records and a chest X-ray was taken approximately seven days after the start of treatment. The presence of lung cavitation was scored by one of the authors (BP) based on the chest X-ray and this score was compared to a radiologist report for agreement.

Respiratory Aerosol Sampling Chamber protocol

The Respiratory Aerosol Sampling Chamber (RASC) has previously been described in detail 16. The RASC consists of a small personal clean space (1.4 m ) in which a participant is seated and engages passively in an exhaled air sampling protocol. Approximately an hour is spent in the chamber following the phases outlined in Wood et al. 16 Briefly, the chamber is sealed and an air purge phase is performed entraining ambient air through high-efficiency particulate arrestance (HEPA) filters for a period of 10 minutes. This is followed by a participant-driven contamination phase in which the chamber is isolated from the external environment and the proportion of exhaled air allowed to rise to a 10% threshold defined by a chamber CO 2 concentration of 4,000 ppm above the ambient level (based on an assumed exhaled air CO 2 concentration of 40,000 ppm). If the target is not reached after 30 minutes have elapsed, the sampling phase is started at a lower exhaled air proportion. After sampling, the chamber is again purged to remove residual Mtb from the air.

Contamination of the sampling chamber was driven primarily by tidal breathing in addition to spontaneous coughing or sneezing. Particles and organisms derived from sources other than breath were minimised by the participant wearing a full-body DuPont Tyvek suit during sampling and an initial purge phase to minimise ambient contamination. Drawing the chamber air over a range of devices allowed mycobacterial detection by microbiological culture or molecular quantitation of genome equivalents.

Particle size measurement

Aerosolized particles were monitored from the final minute of the purge phase and throughout the remainder of the experimental protocol via an aerodynamic particle sizer (APS Model 3321, TSI, Shoreview, MN USA).

Sound recording. Sounds from the inside of the sampling chamber were recorded by microphone and stored as 44.1 KHz 16-bit WAV files using a custom-built recorder application. The files were securely transmitted to a server where automated cough sound analysis can occur. The cough sound analysis divides the input recording into multiple segments of time, and a machine learning algorithm classifies each segment of time as either a cough or not a cough, using characteristics of the signal at that moment in time such as the overall energy within the signal, the distribution of energy across frequencies and the amount of change in energy within the signal within that segment. These classifications are then merged together in order to identify longer segments in time that are continuously cough or non-cough segments, which are then used to identify periods of coughing. This analysis was used to determine cough frequency and cough length for each participant.

Particle capture for microbiological analysis

The sampling phase utilised a six-stage viable Andersen Impactor (Model 10830-EPD, Thermo Scientific, USA) which allowed physical separation of aerosolized particles by size, based on the principle of inertial impaction. These captured particles are incubated to ascertain the number of Mtb bacilli released. The impactor sampled chamber air at a rate of 28 l/min for 10 minutes. Each impactor stage contained a glass Petri dish containing solid Middlebrook 7H10 medium further described below. For participants 14 to 35, a 0.2 µm polycarbonate filter (Sterlitech Corporation, WA USA) of 47 mm diameter was placed on the agar plate abutting the edge, and subsequently removed and analysed using droplet digital PCR (ddPCR).

Direct capture took place using a 0.4 µm microporous polycarbonate filter (Sterlitech Corporation, WA USA) positioned above the participant in an open-faced mount with a 20 l/min flow rate run for 10 minutes. The filter was cut with one half analysed by the microbiological culture method and the other half by ddPCR. A gel filter (Model 12602-37-ALK, Sartorius, Goettingen, Germany) was similarly positioned and run at a flow rate of 20 l/min for 10 minutes. A 0.4 µm polycarbonate filter was placed in-line and downstream of the gel filter. An open-faced, polyester felt filter of 47mm diameter and 1.0μm pore size (American Felt and Filter Company, New Windsor, New York; Lockheed Martin, Alexandria, VA, USA) was used to sample at a high flow rate (approx. 300 l/min) for 10 mins at the end of the experiment and was analysed by ddPCR (see below).

Particle capture for imaging

A Dekati three-stage impactor (PM10, Dekati, Kangasala, Finland) sampling at 30 l/min for ten minutes was used to separate respired particles according to size onto uncoated aluminium foil discs. Assuming a particle density of 1 g/cm3, the three stages collect particles in the size ranges: >14.1 μm, 14.1 μm - 3.5 μm and 3.5 μm - 1.4 μm respectively. A 0.4 µm polycarbonate filter was placed at the outflow of this impactor to capture aerosols of less than 1.4 µm.

The foil discs were air-dried and sterilised by UV-irradiation before imaging, uncoated, by scanning electron microscopy (Zeiss/Leo 1450, ZEISS, Oberkochen, Germany) in secondary electron mode at 10 kv.

Quantification of microbiological specimens

For an individual inside the RASC, the ratio of exhaled air volume to chamber volume is equal to the ratio of excess CO 2 (measured CO 2 less ambient CO 2) to the CO 2 in exhaled breath (approx. 40,000 ppm). Continuous CO 2 monitoring therefore allowed a close approximation of the proportion of exhaled air volume for each participant in the RASC at any given time. The sampled exhaled air volume was the product of this proportion and the air volume sampled by each detection device. Concentrations of colony forming units (CFU) by unit volume of exhaled air could then be established for any of the sampling devices.

Simultaneous measurement of the particle content of the chamber air at the point of microbiological sampling allowed calculation of an aerosol volume per unit volume of air sampled. From these two measures, an approximate Mtb CFU concentration by volume of bio-aerosol was determined (aerosol geometry assumed to be spherical).

Sv = Volume Sampled

*APS sampled at rate of 5L/min; Andersen sampling over 10 minutes

Microbiological detection methods

Culture

Andersen Impactor plates were unloaded in a biosafety cabinet. Filters analysed by culture were placed face-up on solid Middlebrook 7H10 agar supplemented with Glycerol, OADC, and 0.05% Tween80, PANTA (BD) antibiotic mixture and incubated at 37°C for 4–6 weeks. The number of CFU consistent with expected Mtb colony morphology and rate of formation in vitro was recorded, and genomic DNA extracted for PCR confirmation using primers RD9F (5’-gtgtaggtcagccccatcc-3’), RD9R (5’-gctaccctcgaccaagtgtt-3’) and RD9Int (5’gctaccctcgaccaagtgtt-3’) using a protocol developed elsewhere. 18.

Protocol for RD9 confirmation of Mtb Colonies

20 μl reactions containing 2 µl of template DNA are set up with 1x reaction buffer, 200 μM of each dNTP, 0.5–1.0 μM of each primer, 1.5 mM MgCl 2, 1x GC-rich solution, and 2U/50 μl of DNA polymerase. Thermal cycler parameters used for DNA amplification are as follows: denature at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation (94°c for 30s), annealing (65°C for 1min), and extension (72°C for 10min), and a final extension at 72°C for 7 min.

Droplet digital PCR (ddPCR)

Filters were removed from the RASC and transported in 50 ml Falcon tubes. The specimen was processed by vortexing in sterile PBS + 0.05% Tween 80 and centrifuged (3750 rpm for 15 minutes) to harvest the pellet which was lysed for DNA extraction and purification. Quantitative analysis of the RD9 region used a modified protocol and the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen). Primers (RD9/qRTF 5’-tgagtggcgatggtcaacac-3’ and RD9/qRTR 5’-gatggcgttcggaaagaaac-3’) and TaqMan minor groove binder (MGB) probe (RD9/probe 5’-actacgcggcttagtg-3’) were designed using Primer Express software (version 3.0.1). TaqMan MGB probe homologous to the RD9 gene was labelled with 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM). The ddPCR reaction set-up and the run were performed as described previously 19.

An evaluable result for TB DNA was assigned when the following conditions were satisfied: (i) the total number of droplets read in the well was greater than 10,000; (ii) positive droplets possessed a fluorescence intensity above a threshold of 3500; (iii) minimal numbers of intermediate droplets (“rain”) were observed between positive and negative values; and (iv) the observed droplet distribution was consistent with a subpopulation of the positive control which comprised known concentrations of genomic DNA extracted from Mtb H37Rv.

Statistical analysis

Participants were divided into groups according to positive or negative airborne culture. Groups were then compared with unadjusted analyses using Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous variables. Airborne particles and cough data were investigated using Pearson’s correlation. Statistical analyses were performed using R Core Team (2015) 20.

Results

Baseline characteristics and microbiological results

A total of 35 participants were recruited for this study ( Table 1), all of whom had drug-sensitive pulmonary TB defined by a positive GeneXpert sputum. The mean age of the participants was 33 years, of which 57.1% were men and 48.6 % were HIV positive.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of RASC participants.

| Participant | Age | Sex | HIV status

(CD4) |

Previous

TB |

Aerosol

Culture (CFU) |

Aerosol

ddPCR |

Chest XR

Cavitation |

Coughs

per hour |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 30 | M | Negative | N | Positive (11) | Positive | N | N/A |

| 2 | 36 | F | Positive (61) | Y | Positive (2) | Positive | N | 20 |

| 3 | 45 | M | Negative | N | Positive (3) | Positive | N | 22 |

| 4 | 24 | F | Positive (553) | Y | Positive (1) | Negative | N | 63 |

| 5 | 42 | F | Positive (602) | Y | Negative | N/A | Y | 59 |

| 6 | 39 | M | Positive (621) | N | Positive (2) | N/A | N | 11 |

| 7 | 33 | M | Negative | N | Positive (3) | Positive | Y | 25 |

| 8 | 40 | F | Positive (39) | Y | Positive (3) | Positive | N | 27 |

| 9 | 24 | M | Negative | Y | Negative | Positive | N | 2 |

| 10 | 24 | F | Positive (115) | N | Negative | Positive | N | 51 |

| 11 | 29 | M | Positive (128) | N | Negative | Positive | N | 16 |

| 12 | 32 | M | Negative | N | Positive (8) | Positive | Y | 52 |

| 13 | 22 | F | Positive (371) | N | Negative | Positive | N | 71 |

| 14 | 53 | M | Negative | Y | Negative | Positive | N | 36 |

| 15 | 37 | M | Positive (1) | N | Negative | Positive | Y | 7 |

| 16 | 46 | M | Positive (228) | Y | Positive (1) | Positive | N/A | 12 |

| 17 | 28 | F | Positive (211) | N | Negative | Positive | Y | 14 |

| 18 | 38 | M | Positive (66) | Y | Positive (2) | Positive | N | 64 |

| 19 | 46 | M | Negative | N | Negative | Positive | N | 6 |

| 20 | 18 | F | Negative | N | Negative | Positive | Y | 7 |

| 21 | 33 | M | Positive (99) | N | Negative | Positive | Y | 30 |

| 22 | 26 | F | Negative | N | Negative | Unevaluable | N | 8 |

| 23 | 22 | F | Negative | N | Negative | Unevaluable | N | 5 |

| 24 | 33 | F | Positive (43) | N | Negative | Unevaluable | N | 12 |

| 25 | 28 | M | Positive (63) | N | Negative | N/A | N | N/A |

| 26 | 31 | M | Negative | N | Positive (2) | Positive | Y | 9 |

| 27 | 25 | M | Negative | N | Positive (14) | Positive | Y | 33 |

| 28 | 22 | F | Negative | N | Positive (1) | Positive | Y | 49 |

| 29 | 22 | F | Positive (630) | Y | Negative | N/A | Y | 0 |

| 30 | 62 | M | Negative | N | Negative | Negative | N | 3 |

| 31 | 22 | M | Negative | Y | Negative | N/A | Y | 15 |

| 32 | 36 | M | Negative | N | Positive (2) | Positive | Y | 13 |

| 33 | 38 | F | Positive (N/A) | Y | Positive (4) | Positive | N/A | 136 |

| 34 | 26 | F | Negative | N | Negative | Positive | N | 20 |

| 35 | 52 | M | Negative | N | Negative | Positive | N | 0 |

N/A = not tested

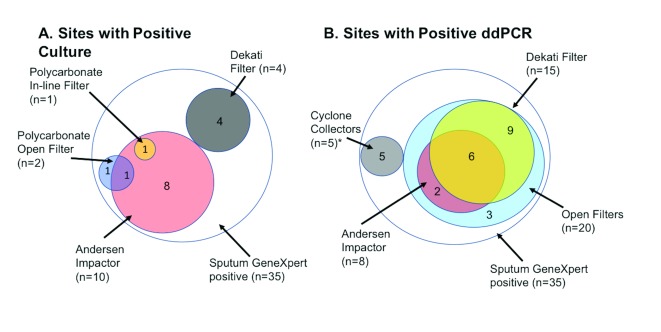

15 participants (42.9%) had a positive bio-aerosol mycobacterial culture, which was defined as one or more CFU detected on any of the sampling devices ( Figure 1A). 59 CFU exhibited the morphologies and growth rates characteristic of Mtb grown in vitro on solid media, and this was confirmed by RD9 genotype in 37 cases. For the other putative Mtb CFU, RD9 confirmation was not possible owing to fungal contamination. The median amongst the positives was 2.5 CFU with a range of 1–14. The greatest yield was with the viable Andersen cascade impactor which gave a median concentration of 0.09 CFU per litre of air sampled (IQR: 0.07 to 0.3 CFU/L). For the same device, the calculated median concentration of CFU in exhaled bio-aerosol was 4.5×10 CFU/ml (IQR: 2.9×10 –5.6×10 ).

Figure 1.

Euler Diagrams demonstrating successful detection sampling modalities for A. mycobacterial culture and B. ddPCR (25 positive out of 27 successfully tested). *Cyclone Collectors were added for the later participants. These included a NIOSH two-stage cyclone aerosol sampler (2 positive out of 4 participants sampled) and Coriolis µ biological air sampler (3 positive out of 3 participants sampled).

Mean CFU per litre was 0.006 for the polycarbonate filters in the open-faced filter. The gel filter produced no positive results, whereas the downstream in-line polycarbonate filter produced a concentration of 0.003 CFU per litre of exhaled air. The concentration inferred from the Dekati outflow polycarbonate filter was 0.008 CFU per litre of exhaled air.

Samples from five of the participants were not tested by ddPCR, and a further three participants’ specimens were unevaluable. 25 participants (92.6%) out of 27 successfully tested had a positive ddPCR result from one or more of the sampling devices ( Figure 1B). Of all filters tested for all participants, 118/137 (86.1%) were positive for Mtb. By either method, Mtb was detected in 27 out of 35 participants (77.1%).

Production of a culturable bio-aerosol was not statistically associated with any of the recorded baseline characteristics, including cavitary disease on chest imaging and presence of a positive sputum smear whether treated as a binary (positive/negative) or continuous outcome. However, an association was observed between culturable bio-aerosol production and greater spontaneous cough frequency during the experimental protocol (see Table 2).

Table 2. Traditional predictors of infectiousness stratified by Aerosol Culture.

Categorical variables were compared using Fisher exact tests and continuous variables using a Wilcoxon rank sum test.

| Aerosol

Negative |

Aerosol

Positive |

p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 20 | 15 | ||

| Sputum smear (%) | Positive | 10 (50.0) | 9 (60.0) | 0.807 |

| Cavitary disease (%) | Positive | 7 (35.0) | 6 (46.2) | 0.782 |

| Cough count (median [IQR]) | 12 [5.5, 25] | 26 [15, 51] | 0.022 |

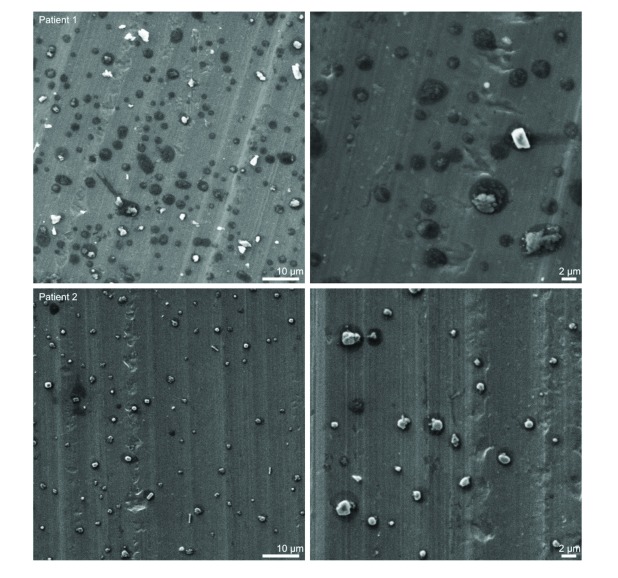

Imaging of respired particulate matter. Representative images from two participants captured from SEM of the foil discs from the Dekati impactor are show in Figure 2. Numerous particles of variable morphology are shown which appear to comprise organic matter derived from patient lung or respiratory tract. Note the “halo” structures (dark shadows) surrounding each particle which may be indicative of droplet nuclei impaction.

Figure 2. Respired particulate matter from two TB infected individuals captured on the lower plate (3.5 μm – 1.4 μm) of a Dekati three-stage impactor (PM10, Dekati, Kangasala, Finland) sampling at 30 l/m onto uncoated aluminium foil discs.

Particle analysis

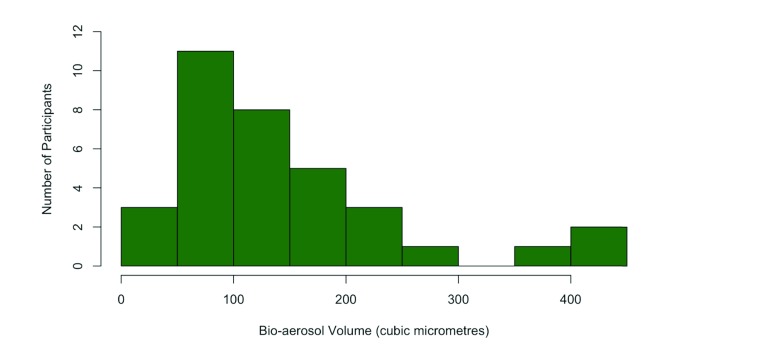

Particle counts measured by the aerodynamic particle sizer (APS) were widely variable between participants. In general, counts gradually increased throughout the time spent in the chamber during the contamination phase. Comparison of particles among participants was performed by summing all the particles in the 1–5 µm range over a 5 minute period after 20 minutes of the contamination phase had elapsed. This result was divided by the number of litres sampled by the APS (25 L; 5 mins at flow rate of 5 l/min) yielding a 1–5 µm particle count per litre at the point of maximal contamination. Participant-derived particle counts were taken to be the difference between the figure at maximal contamination and the 1–5 µm particle count per litre concentration at the end of the purge phase. The median for the 35 pulmonary TB participants was 23.9 counts/l (IQR 14.8–47.7). A single outlier was excluded from this and the subsequent analysis owing to a markedly elevated particle count (>4 standard deviations from the mean), possibly due to environmental contamination of the chamber. Figure 3 shows a histogram of the 35 participants’ bio-aerosol production calculated as volume.

Figure 3. Histogram of bio-aerosol volume per litre of exhaled air for RASC participants.

A strong correlation was observed between CO 2 production rate and particle production with a Pearson’s correlation coefficient of 0.54 (95% CI 0.24 to 0.75; p<0.001) for the active TB participants. No relationship was elucidated between particle production and airborne culture when treated as a binary variable or quantitatively. No other significant correlations were inferred when comparing particle production with age, sex, HIV status, body mass index, severity of chest X-ray, presence of radiologically apparent cavitation or sputum smear status.

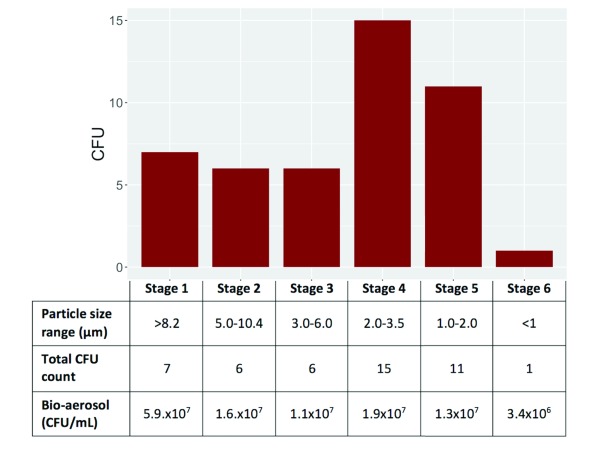

Concentration and size distribution of bio-aerosol culture

Of the 15 participants with positive bio-aerosol cultures, 10 had one or more CFU on the viable Andersen impactor. CFU were found on all stages of the impactor ( Figure 4). In addition, for one of the participants, one CFU was found on the polycarbonate filter located at the Andersen impactor outflow. Particle counts, measured by the APS, and matched by size with the impactor stages were used to establish the aerosol volume as a denominator. The calculated CFU count per millilitre of bio-aerosol is displayed in Figure 4. Notably, the concentration of CFU per ml of bio-aerosol was 100 to 1000-fold higher than that found in the sputum (up to 10 CFU per ml).

Figure 4. Histogram of total number of M. tuberculosis colony forming units in each of the 6 stages of Andersen impactors.

The size range of collected particles and the calculated mean concentrations of CFUs per millilitre of captured bio-aerosol are shown in table.

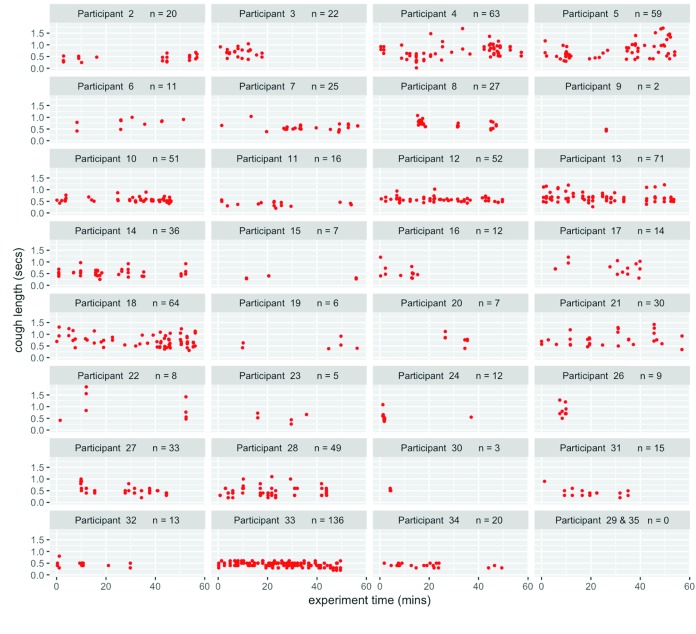

Cough analysis

To ascertain whether a unique cough signature was associated with each participant, sound recordings for the full period spent in the chamber were analysed, and the number and duration of coughs determined ( Figure 5). Sound recording was not performed for the first and 25th participants. No statistically significant correlation was detected between cough frequency and particle production (Spearmans’ rank correlation coefficient of 0.11; p=0.55) but, as mentioned before, there is an association between culturable bio-aerosol production and cough frequency (Wilcoxon rank sum test p=0.022).

Figure 5. Plot of recorded coughs for each participant throughout the experiment.

Fungal contamination

A significant percentage of fungal and bacterial (non- Mtb) contamination was found on both the solid 7H10 medium used in the impactor and from the filters. Likely fungal contamination was recorded on one or more of the impactor plates for 26% of participants, 6% of the gel filters, and 37% of polycarbonate filters. Bacterial contamination was identified on one or more impactor plate for 20% of participants, 3% of gel filters and 11% of polycarbonate filters. In combination, these data highlight the technical challenges stemming from the requirement for long-term incubation of environmentally exposed plates in order to enable Mtb CFU formation.

Discussion

This study utilised a novel collection system to identify and quantify the Mtb content of environmental bio-aerosols produced by newly diagnosed but untreated TB patients. Viable impaction onto solid media and capture onto filters allowed culture of Mtb organisms in nearly 40% of subjects and Mtb DNA amplification of filtered bio-aerosol material in more than 90% of subjects in whom the assay was successfully performed. The RASC system minimized expired bio-aerosol dilution by using a small chamber volume and minimal fresh air ventilation while available bio-aerosol was maximized by the length of time spent in a confined space and by limiting the study to untreated TB patients 21. The sensitivity of the RASC therefore extends the earlier work of Wells and Riley 4 and Fennelly 12 by increasing the proportion of patients in which airborne Mtb could be isolated and sampling bio-aerosols likely to remain in the environment for a period of time. Further sensitivity improvements may be possible with an increase in the volume of exhaled air sampled.

The intriguing observation that Mtb-specific RD9 DNA sequences could be detected in almost all patients with the ddPCR assay raises fundamental questions as to what these DNA sequences represent. Future work is aimed at resolving whether the Mtb DNA signal was from DNA incorporated in viable or non-viable Mtb cells or, possibly, cell-free DNA. Recent studies have identified differentially culturable Mtb in sputum samples 22,23. Further studies exploring the increased magnitude of PCR signal compared with CFU could explore whether differentially culturable organisms such as those reported to occur in sputum 20, or produced in vitro by rifampicin treatment of starved cultures of Mtb, occur in patient-generated bio-aerosols.

The finding of organisms throughout the impactor stages supports the premise that Mtb is indeed incorporated within respirable bio-aerosols. Analysis of the CFU distribution in conjunction with the size distribution of the measured bio-aerosols demonstrates a similar order of magnitude for the Mtb concentration in 1–10 μm particles across all 6 stages of the Andersen impactor. This may imply that incorporation of the bacillus into the bio-aerosol is simply proportional to aerosol volume and not specific to aerosol size.

The concentration of CFU in bio-aerosol material was approximately 1–2 orders of magnitude higher than the concentration of CFU in sputum and represented a median production rate of approximately 1 CFU per minute in exhaled breath (1 CFU per 9 litres). Culturable Mtb isolated in cough-derived aerosols has been shown to be associated with transmission risk 15. The presence of culturable Mtb organisms in such high concentrations in respirable bio-aerosols does suggest probable host physical or immunologic control to limit Mtb infection becoming widespread throughout the respiratory system.

Caveats for our study include the relatively small number of participants, all with drug-sensitive TB; these findings will need to be confirmed in larger numbers and in drug-resistant TB cases. The ddPCR assay is a very sensitive and quantitative assay but we applied extremely stringent criteria to ensure a high specificity at a cost of loss of sensitivity. The culturability of Mtb may have been underestimated as we relied on solid media culture and occasionally lost cultures due to fungal overgrowth. We plan to augment solid media culture with more sensitive liquid capture and culture methodologies in future studies.

Conclusions

The use of a sensitive sampling system demonstrated a high number of Mtb organisms in respiratory bio-aerosols. This finding highlights the great potential for breath sampling, as both a research and a clinical tool. Generating specimens by this method selects a subpopulation of Mtb organisms that is very likely to be phenotypically distinct. Since this subpopulation is necessarily involved in disease transmission between hosts, further investigation would be of great interest.

In the clinical setting, a refined sampling system could be used as non-invasive diagnostic test of particular benefit in sputum-scarce or sputum smear-negative patients, a group known to be responsible for a proportion of transmission 24. Combining breath sampling with a molecular detection test could produce a rapid point-of-care system with high sensitivity, although this may be at the expense of false positives from non-viable organisms in previously treated individuals as has been observed with GeneXpert RIF assay 25. Such a test may have a clinical role as a measure of infectivity in the hospital setting or, conceivably, for mass screening to identify sub-clinical cases in high burden communities.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings reported in this study have been uploaded to OSF: https://osf.io/3kfgy/. DOI, 10.17605/OSF.IO/3KFGY 26.

Data are available under the terms of the Creative Commons Zero "No rights reserved" data waiver (CC0 1.0 Public domain dedication)

Dataset 1. Particle Data.

Particle data collected throughout the experiment. Recorded as a raw count of particles separated into size bins for aerodynamic diameter. The headers represent the lower limit of the size bin (in microns).

Dataset 2. Mtb Aerosol Culture.

Results for Mtb culture testing for multiple sampling modalities. The number corresponds to colony forming units (CFU).

Dataset 3. Mtb Aerosol ddPCR.

Results for Mtb ddPCR test for multiple sampling modalities. A score of 1 corresponds to a positive result, -1 a negative result and 0 is an indeterminate result.

Dataset 4. Cough Data.

Results of sound analysis to identify spontaneous coughs during the experiment.

Funding Statement

Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation [OPP1116641] and the South African Medical Research Council (MRC), with funds from National Treasury under the Economic Competitiveness and Support Package [MRC-RFA-UFSP-01-2013/CCAMP].

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

[version 2; referees: 3 approved]

References

- 1. WHO: Global Tuberculosis Report.2016. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dowdy DW, Chaisson RE: The persistence of tuberculosis in the age of DOTS: reassessing the effect of case detection. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87(4):296–304. 10.2471/BLT.08.054510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Middelkoop K, Mathema B, Myer L, et al. : Transmission of Tuberculosis in a South African Community With a High Prevalence of HIV Infection. J Infect Dis. 2015;211(1):53–61. 10.1093/infdis/jiu403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Riley RL, Mills CC, Nyka W, et al. : Aerial dissemination of pulmonary tuberculosis. A two-year study of contagion in a tuberculosis ward. Am J Hygiene. 1959;70(2):185–196. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nardell EA: Catching droplet nuclei: toward a better understanding of tuberculosis transmission. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169(5):553–554. 10.1164/rccm.2401003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schafer MP: Detection and Characterization of Airborne Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Ra Particles, A Surrogate for Airborne Pathogenic M. tuberculosis. Aerosol Sci Tech. 1999;30(2):161–173. 10.1080/027868299304750 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mastorides SM, Oehler RL, Greene JN, et al. : The detection of airborne Mycobacterium tuberculosis using micropore membrane air sampling and polymerase chain reaction. Chest. 1999;115(1):19–25. 10.1378/chest.115.1.19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen PS, Li CS: Quantification of airborne Mycobacterium tuberculosis in health care setting using real-time qPCR coupled to an air-sampling filter method. Aerosol Sci Tech. 2005;39(4):371–376. 10.1080/027868290945767 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vadrot C, Bex V, Mouilleseaux A, et al. : Detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex by PCR in hospital air samples. J Hosp Infect. 2004;58(4):262–267. 10.1016/j.jhin.2004.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wan GH, Lu SC, Tsai YH: Polymerase chain reaction used for the detection of airborne Mycobacterium tuberculosis in health care settings. Am J Infect Control. 2004;32(1):17–22. 10.1016/S0196-6553(03)00090-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Matuka O, Singh TS, Bryce E, et al. : Pilot study to detect airborne Mycobacterium tuberculosis exposure in a South African public healthcare facility outpatient clinic. J Hosp Infect. 2015;89(3):192–196. 10.1016/j.jhin.2014.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fennelly KP, Martyny JW, Fulton KE, et al. : Cough-generated aerosols of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a new method to study infectiousness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169(5):604–9. 10.1164/rccm.200308-1101OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Williams CM, Cheah ES, Malkin J, et al. : Face mask sampling for the detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in expelled aerosols. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e104921. 10.1371/journal.pone.0104921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jones-Lopez EC, Namugga O, Mumbowa F, et al. : Cough Aerosols of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Predict New Infection: A Household Contact Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(9):1007–1015. 10.1164/rccm.201208-1422OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jones-López EC, Acuña-Villaorduña C, Ssebidandi M, et al. : Cough Aerosols of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the Prediction of Incident Tuberculosis Disease in Household Contacts. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(1):10–20. 10.1093/cid/ciw199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wood R, Morrow C, Barry CE, 3rd, et al. : Real-Time Investigation of Tuberculosis Transmission: Developing the Respiratory Aerosol Sampling Chamber (RASC). Cardona P-J, ed. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0146658. 10.1371/journal.pone.0146658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wells W: Airborne Contagion and Air Hygiene.Harvard University Press, Cambridge.1955;423 Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 18. Parsons LM, Brosch R, Cole ST, et al. : Rapid and simple approach for identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex isolates by PCR-based genomic deletion analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40(7):2339–45. 10.1128/JCM.40.7.2339-2345.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Singh V, Brecik M, Mukherjee R, et al. : The complex mechanism of antimycobacterial action of 5-fluorouracil. Chem Biol. 2015;22(1):63–75. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2014.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. R Core Team: R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria.2016. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 21. Issarow CM, Mulder N, Wood R: Modelling the risk of airborne infectious disease using exhaled air. J Theor Biol. 2015;372:100–6. 10.1016/j.jtbi.2015.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chengalroyen MD, Beukes GM, Gordhan BG, et al. : Detection and Quantification of Differentially Culturable Tubercle Bacteria in Sputum from Patients with Tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194(12):1532–1540. 10.1164/rccm.201604-0769OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mukamolova GV, Turapov O, Malkin J, et al. : Resuscitation-promoting factors reveal an occult population of tubercle Bacilli in Sputum. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(2):174–80. 10.1164/rccm.200905-0661OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tostmann A, Kik SV, Kalisvaart NA, et al. : Tuberculosis transmission by patients with smear-negative pulmonary tuberculosis in a large cohort in the Netherlands. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(9):1135–1142. 10.1086/591974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Boyles TH, Hughes J, Cox V, et al. : False-positive Xpert® MTB/RIF assays in previously treated patients: need for caution in interpreting results. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2014;18(7):876–8. 10.5588/ijtld.13.0853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Patterson B, Morrow CD, Singh V, et al. : Paper: Mtb in Bioaerosols (October 2017).2017. 10.17605/OSF.IO/3KFGY [DOI] [Google Scholar]