Abstract

The glucocorticoid receptor-dependent activation of plant transcription factors has proven to be a powerful tool for the identification of their direct target genes. In the absence of the synthetic steroid hormone dexamethasone (dex), transcription factors fused to the hormone-binding domain of the glucocorticoid receptor (TF-GR) are held in an inactive state, due to their cytoplasmic localization. This requires physical interaction with the heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) complex. Hormone binding leads to disruption of the interaction between GR and HSP90 and allows TF-GR fusion proteins to enter the nucleus. Once inside the nucleus, they bind to specific DNA sequences and immediately activate or repress expression of their targets. This system is well suited for the identification of direct target genes of transcription factors in plants, as (A) there is little basal protein activity in the absence of dex, (B) steroid application leads to rapid transcription factor activation, (C) no side effects of dex treatment are observed on the physiology of the plant, and (D) secondary effects of transcription factor activity can be eliminated by simultaneous application of an inhibitor of protein biosynthesis, cycloheximide (cyc). In this chapter, we describe detailed protocols for the preparation of plant material, for dex and cyc treatment, for RNA extraction, and for the PCR-based or genome-wide identification of direct targets of transcription factors fused to GR.

Keywords: Dexamethasone, Direct target, Glucocorticoid receptor, Heat shock protein 90, Inducible system, Transcription factor

1 Introduction

Transcription factors (TFs) control many processes in multicellular eukaryotes, from development and growth to response to stress and disease [1]. To understand how transcription factors execute their roles, it is critical to identify their immediate early (direct) targets at a given stage and in a given tissue.

Overexpression of transcription factors is often used to see enhanced effects on downstream target gene expression. However, the resulting transgenic plants frequently show early developmental effects. As development proceeds, secondary morphological and gene expression effects accumulate. Likewise, constitutive TF loss-of-function mutants accumulate molecular changes over time that are indirect consequences of the initial transcriptional defect. Conditional and inducible transgene expression allows us to elucidate primary roles or rapid effects of transcription factors of interest in a specific region. Three different inducible gene expression systems are commonly used that rely on posttranslational activation of TFs. All are based on mammalian nuclear receptors, the glucocorticoid receptor (GR; discussed in detail below), the β-estradiol receptor [2–4], or the androgen receptor [5] systems. Another versatile system for transcriptional activation is the ethanol inducible system [6, 7].

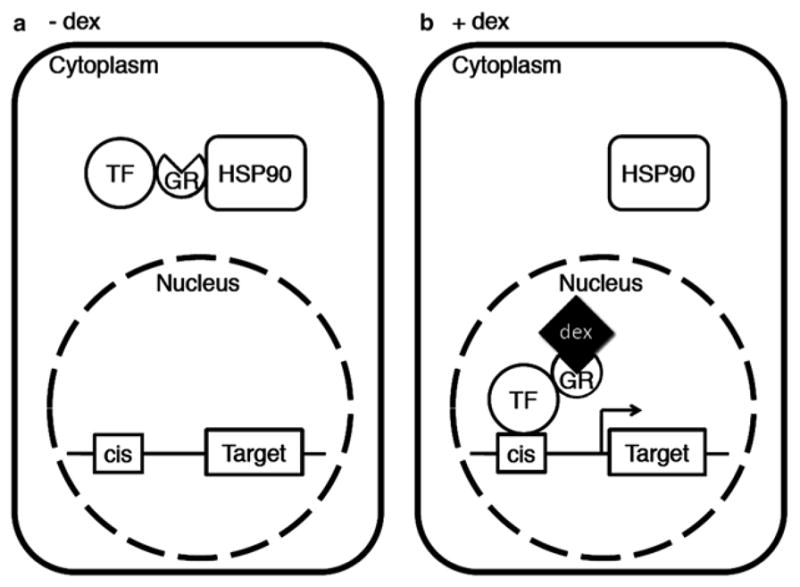

Among the systems for posttranslational activation, the GR system has been most widely used to identify direct downstream target genes of transcription factors. In the absence of a steroid hormone such as dexamethasone (dex), the TF-GR fusion protein forms a cytoplasmic complex with heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) and cannot enter the nucleus where it exerts its effect (see Fig. 1a). Activation of TF-GR fusion protein function occurs upon application of exogenous steroid hormone, which releases the transcription factor from its cytoplasmic retention [8] (see Fig. 1b). Because nuclear translocation does not require subsequent protein synthesis, activation of the fusion protein is very rapid. In addition, indirect effects of transcription factor activation, which can occur rapidly, can be blocked by simultaneous application of a protein synthesis inhibitor [9]. Finally, no major side effects caused by dex have been reported in plants [10–13]. Thus, this system is suitable for analyzing the direct effects of transcriptional regulators on gene expression.

Fig. 1.

Target gene expression by activating transcription factor-GR fusion protein. (a) In the absence of dex, TF-GR fusion protein is retained in the cytoplasm by virtue of its interaction with the HSP90 complex. (b) Nuclear entry of the fusion protein by dex application triggers rapid induction of target gene expression

In the mid-1990s [14, 15], it was shown that although plants do not encode steroid hormones of the type sensed by mammalian GR, plant HSP90 does bind mammalian GR and retains transcription factor-GR fusions in the cytoplasm [16]. Thus, plant cells have a highly conserved set of cellular components required to mediate mammalian glucocorticoid hormone action [17]. Nanomolar concentrations of dex are sufficient to activate GR fusion proteins [15]. After a single dex treatment, gene expression changes were seen within less than 1 h [18, 19]. Dependent on the dose and duration of the dex treatment, GR fusion proteins can stay localized in nuclei for up to 2 days [20]. A 2-h treatment with 5 μM dex led to activation of the LEAFY (LFY) TF-GR fusion protein for about 12 h [16]. The GR fusion technique, combined with micro-array or RNA-seq studies, has allowed for identification of direct targets of many plant transcription factors on a genome-wide scale [18–32]. After identification of immediate early target genes, it is possible to directly test TF-GR binding to the regulatory regions of such genes by chromatin immunoprecipitation by using commercial anti-GR antibodies [33].

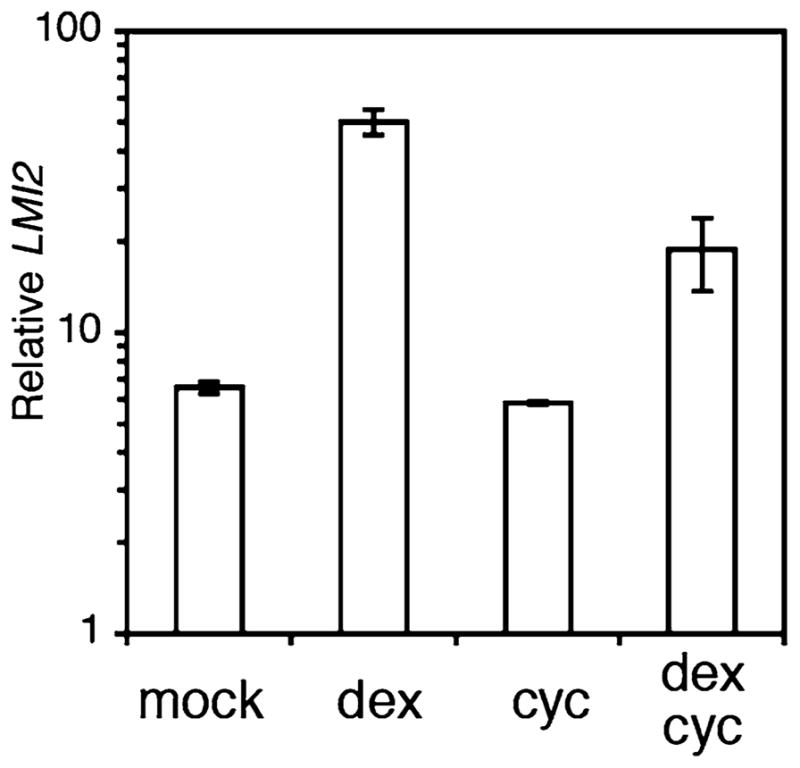

In this chapter, we describe protocols that can be used to identify direct targets of transcription factors of interest through the GR fusion technique. An example of gene expression changes observed after dex activation using the GR inducible system is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

LMI2 is a direct target of the meristem identity regulator LFY. LMI2 mRNA levels in 35S::LFY-GR seedlings treated with mock or dexamethasone (dex) solution in the absence or presence of the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (cyc). Data are from transcription profiling experiments conducted by William et al. [19]

2 Materials

2.1 Generation of TF-GR Transgenic Lines

Hormone binding domain (amino acid 508–795) of the rat glucocorticoid receptor.

GR antibody (Santa Cruz; P-20, sc-1002) [33].

2.2 Dex Treatment of Plant Material

Transgenic plants expressing the TF of interest fused to GR.

Dexamethasone (Sigma) (20 mM) in DMSO or 100 % ethanol. Stocks can be stored at −20 °C for a week.

Cycloheximide (Sigma) (100 mM) in 100 % ethanol. Stocks can be stored at −20 °C for a few months.

Silwet L-77 (GE Silicones).

Sterile water.

1/2 MS plates (0.5 g/L MES, ½ MS salt 0.8 % agar, pH 5.7).

Dexamethasone/cycloheximide-containing 1/2 MS plates (see Note 1).

Nylon mesh to facilitate seedling transfer (Nitex Cat 03-100/44, Sefar).

Spray nozzle.

Paintbrush.

Watering can.

Liquid nitrogen.

2.3 RNA Extraction

Liquid nitrogen.

Mortar and pestle.

TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies; Cat. no. 15596-026).

Chloroform.

Isopropanol.

High salt solution (Takara; Cat. no. 9193).

75 % ethanol.

RNase-free water.

RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen; Cat. no. 74104 or 74106).

RNase-free DNase set (Qiagen; Cat. no. 79254).

1.5 ml tubes.

2.4 PCR Identification of Direct Targets by RT-PCR

SuperScript III first-strand synthesis system for RT-PCR (Invitrogen; Cat. no. 18080-051).

Power SYBR green master mix (ABI; Cat. no. 4367659).

Gene-specific primer sets.

Control gene primer sets.

2.5 Genome-Wide Identification of Direct Targets by Microarray

Nugen Ovation® RNA Amplification System V2.

Affymetrix GeneChip® Arabidopsis ATH1 Genome Arrays.

NanoDrop ND-1000 UV–VIS Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.).

3 Methods

3.1 Generation of TF-GR Transgenic Lines

The GR inducible system can be used to induce gain-of-function effects at a given stage of development. The TF-GR protein can be driven by a constitutively active or a tissue-specific promoter. A constitutively active promoter may provide stronger induction, whereas tissue-specific promoters allow one to address the function of the TF in a tissue of interest. Several considerations are important for generating transgenic lines. One way to employ TF-GR fusion proteins is by driving their expression from a strong constitutive or tissue-specific promoter (e.g., the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter or the CLAVATA3 (CLV3) promoter, which is expressed in the stem cells of shoot apices) [34, 35] and transform wild-type plants with 35S::TF-GR or pCLV3::TF-GR. One would then induce the TF by dex treatment just prior to the time when it becomes upregulated in planta. Since the experiment is performed in wild-type plants at the right developmental stage, this approach ensures presence of potential TF cofactors that may be required for full transcriptional activity. However, this method is based on over-expression, which may cause some changes in expression of genes that are not bona fide TF targets. Alternatively, the TF-GR fusion protein can be expressed from the endogenous promoter at wild-type levels and transformed into the null mutant background. Dex-dependent activation of a transcription factor important for root patterning, called SHORTROOT (SHR), expressed from its own promoter (pSHR::SHR-GR) in shr mutants [23, 29] allowed identification of direct SHR target genes. This approach minimizes potential “off-target” effects. However, it may fail to identify TF targets for which a cofactor is required whose expression is directly or indirectly controlled by the TF of interest. Many TFs induce their own cofactors [29].

Some GR fusion proteins are constitutively active and constitutively nuclear localized. For example, fusion of a SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling ATPase to GR led to constitutive activity, presumably because these proteins are components of large complexes, many components of which have nuclear localization signals that are not all masked by the HSP90 interaction (Wagner lab, unpublished data). Other TF-GR fusion proteins are slightly leaky, one example is pUBQ10::MP-GR [36]. A slight leakiness can be overcome if one reduces the copy number the fusion protein of interest by working with hemizygous plants.

Fuse the transcription factor of interest to GR and the promoter of choice in a binary vector (see Notes 2 and 3).

Transform plants with the TF-GR construct by floral dip and select resistant plants according to standard protocols [37].

Select several T1 transgenic lines that [based on Western blotting analysis with a GR-specific antibody] produce full-length fusion proteins. In some cases, we saw constitutively active truncated versions of the fusion protein in transgenic plants.

Select T2 transgenic lines with a single copy insertion site by determining the segregation ratio of the transgene. If no leakiness of the GR fusion is observed, use of homozygous insertion lines is advisable for all downstream applications.

Test for an inducible gain-of-function phenotype or for the dex-dependent rescue of the null mutant phenotype (see Note 4). For phenotypic analysis, multiple dex treatments or prolonged exposure to dex is often required.

3.2 Dexamethasone Treatment Conditions

In most studies, a synthetic steroid hormone, dexamethasone, is used. Less stable steroids like triamcinolone acetonide may be useful for transient induction [15], although transient activation was also possible with dex [38]. The system can be used to induce TF activity in a concentration-dependent manner. It has been reported that a good correlation between dex concentration and induction of gene expression is observed in the concentration range from 0.1 to 50 μM. A good starting concentration is 5 μM.

Five different types of treatments have been performed successfully. (a) Submersion of plants in dex solution, (b) growing plants on MS plates containing dex, (c) spraying plants with dex solution, (d) painting of plants with dex solution, and (e) watering soil-grown plants with dex solution. For gene expression analysis to identify direct targets and/or multiple treatments, we recommend short dex treatments (methods a, b and c).

Treatment duration and dex concentration needed for the activation of gene expression depend mostly on the tissue sampled, but also on the transcription factor tested. Lower dex concentration and treatment durations are needed for tissues that take up solutions readily such as roots and young seedlings. Tissues with a cuticular layer need to be treated with higher dex doses and for longer durations and dex solutions frequently include a surfactant, such as Silwet L-77 (see below). Optimal duration time and concentration for gene expression is best established by performing a time course series in same age plants treated with dex-containing or a mock solution and monitoring by qRT-PCR expression of a known or candidate target of the TF of interest. The shortest treatment conditions that give a reproducible alteration in target gene expression should be chosen for further studies.

3.2.1 Submersion

This approach has been used for seedlings grown on MS plates (tissues from 3 to 21 day after germination) [30]. Transient induction was also possible [38]. Induction by this treatment is rapid and uniform. It is advisable to use sterile conditions.

Grow transgenic plants on MS medium.

Flood the seedlings in plates with water containing dex and/or cyc (10 μM) for up to 8 h (see Note 5).

For RNA analyses: harvest, gently dry (using a paper towel), and freeze seedlings immediately in liquid nitrogen (see Notes 6 and 7).

For phenotypic analyses: rinse the seedlings in sterile water and transplant them onto soil (see Note 8).

3.2.2 Growth on MS Dex Plates

This approach has been used on seedlings up to 21 days of age. Quantitative response increases with higher dex doses or treatment duration. Although dex treatment on plates is uniform and consistent, this method mainly works for tissues in direct contact with the media, such as roots [23]. Sterile conditions are needed.

Grow transgenic plants on MS plates with mesh on top of the agar.

Transfer all the seedlings to MS plates with dex and/or cyc by lifting and moving the mesh with seedlings.

Grow the seedlings on MS plates with dex and/or cyc from several hours (for RNA analysis) or on plates with dex for several days (for phenotypic analysis). Seedlings can also be transplanted either onto MS plates or soil for further phenotypic analyses.

For RNA analyses: harvest, gently dry (using a paper towel), and freeze seedlings immediately in liquid nitrogen (see Notes 6 and 7).

3.2.3 Spraying

This treatment can be used to test plants of all developmental stages. Sterile conditions are not required; this can reduce setup time. Quantitative response increases with higher doses or duration of treatment.

Grow transgenic plants either on MS plates or soil.

Spray plants with dex and/or cyc-containing solution supplemented with freshly diluted Silwet L-77 at 0.015 % (v/v) (see Notes 9 and 10).

Harvest and freeze plants after the intended incubation period in liquid nitrogen.

For phenotypic analyses, observe growth after additional treatment and/or growth.

3.2.4 Painting

This treatment is convenient for leaves and inflorescence stems. The primary disadvantage is that uniform and consistent dex treatments are difficult. Thus, care must be taken that the treatment is uniform between tissues and plants. If a tissue specific promoter of interest is available, it is better to drive expression of TF-GR from such a promoter and use methods 1, 2, or 3.

Grow transgenic plants either on MS plates or soil.

Paint plants using a paintbrush (any small paintbrush will work) with dex solution containing freshly diluted Silwet L-77 to a concentration of 0.015 % (v/v).

Harvest and freeze plants after the intended incubation period in liquid nitrogen.

3.2.5 Watering

This treatment can be used on plants of all developmental stages. The primary disadvantage is that dex remains active in a soil for some time. Also, it takes time for dex to reach the tissue of interest. Thus, this treatment is not suitable for transient induction.

Grow plants on soil.

Water plants with dex-containing water. 10 μM dex is a good starting concentration.

Observe phenotype.

3.3 Simultaneous Treatment with Dex and Cyc or Other Compounds

Submersion, growth on plates and spraying also lend themselves to multiple simultaneous treatments [16, 23, 40]. Simultaneous dex and protein synthesis inhibitor (cyc) treatments have been performed to identify direct downstream targets of transcription factors of interest [9, 16, 19, 28, 39, 40]. Inhibition of protein synthesis prevents accumulation of primary target transcription factors that subsequently exert their effect on gene expression (indirect effect). The protein synthesis inhibitor cyc is active for ca. 6 h after application (see Note 11). Thus, if the induction requires more than 4 h, we recommend that the old solution needs be replaced with fresh solution (submersion), or by placement of seedlings on a fresh plate, or by an additional spray application.

Simultaneous dex induction of a GR-inducible transcription factor and of an EtOH-inducible factor [6] has been used successfully to modulate abundance of two genes at the same time [39]. In that case, dex needs to be solubilized in a solvent such as methanol or DMSO that does not trigger the EtOH-inducible AlcA/AlcR system. Also, plant hormones (auxin, gibberellin) or hormone biosynthesis inhibitors (paclobutrazol) have been applied together with dex [39]. Mock solutions containing the solvent at the relevant concentration need to be added to each single control treatment. One could also activate two transcription factors sequentially by fusing TF1 to GR and TF2 to the androgen receptor [5].

3.4 RNA Extraction and Purification

The purity of RNA is important for consistent RT-PCR results. Thus, we strongly recommend RNA purification after normal extraction. To avoid false positives and background, elimination of genomic DNA is necessary.

Grind tissues to a fine powder using a mortar and pestle, keeping the tissue frozen throughout (see Notes 12 and 13).

Add powdered tissue to 1.5 ml tube containing 1 ml TRIzol reagent.

Vortex for 20 s and leave at room temperature while processing the other samples. Repeat for all samples.

Add 200 μl of chloroform to each tube and vortex for 30 s.

Leave at room temperature for 10 min.

Centrifuge at 15,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C.

Transfer aqueous layer to fresh 1.5 ml tube.

Add 250 μl of isopropanol and 250 μl of high salt solution to precipitate nucleic acids enriched in RNA and vortex samples for 15 s.

Incubate samples at room temperature for 10 min.

Centrifuge at 15,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C (see Note 14).

Discard supernatant, leaving only the RNA pellet.

Add 1 ml of 75 % ethanol to wash the pellet.

Centrifuge at 15,000 × g for 5 min at room temperature.

Discard supernatant and air-dry the pellets for 5 min.

Dissolve RNA pellets in 100 μl of RNase-free water by incubating at 60 °C for 10 min.

Purify RNA using RNeasy Mini RNA purification Kit and DNase digestion according to manufacturer’s protocol.

3.5 RT-PCR and Real-Time PCR

To obtain high yield of full-length cDNA, it is important to use reverse transcriptase with higher thermostability and reduced RNase H activity. SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) is one of the most widely used cDNA synthesis enzymes.

To reduce assay setup and running costs, we often use SYBR green for real-time PCR rather than TaqMan probes. Power SYBR dye amplifies and fluorescently labels any double-stranded DNA sequence. To avoid generating false positive signals, it is important to have well designed primers that amplify specific target sequences. To design primer sets, we recommend using Primer3 (bioinfo. ut.ee/primer3-0.4.0/). Primer sets should be tested for efficient amplification by performing qPCR with genomic DNA or (if exon/intron junction primers are used cDNA derived from tissues where the gene of interest is highly expressed) (see Note 15). The amplification efficiency can be improved considerably if the length of the amplified fragment is between 60 and 150 bp. The qPCR should be in the linear range of amplification.

Synthesize cDNA using Superscript III kit according to manufacturer’s protocol.

Proceed to quantitative PCR using gene-specific primers. PCR is carried out in a final volume of 25 μl containing: 12.5 μl Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (2×); 2 μl cDNA template; 0.5 μl primers (forward and reverse, 10 μM each); and 9.5 μl sterile ddH2O. The PCR products are amplified using the following conditions: 95 °C for 10 min; 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min (Cycling stage); 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 1 min, and 95 °C for 15 s (Melting Curve Stage) (see Note 16).

3.6 Microarray

Genome-wide identification of direct targets of the transcription factor of interest can be accomplished using the GR-inducible system in combination with microarrays or RNA-seq. Valid comparisons for microarray or RNA-seq analysis include dex versus mock, and dex/cyc versus cyc treatments of seedlings containing the transcription factor-GR fusion. The dex versus mock comparison will identify both direct and indirect transcriptional responses to induction of the transcription factor of interest, while the dex/cyc versus cyc comparison will identify direct targets. Note that it is essential to compare a dex/cyc-treated sample to cyc alone, since cyc is known to cause changes in transcription in plants [19]. To increase the level of confidence in identified targets, it is possible to perform both comparisons (dex/cyc vs. cyc, and dex vs. mock) and take the intersection of differentially expressed genes as the high-confidence direct targets [19]. Direct targets can also be identified by combining microarray or RNAseq analysis of dex vs. mock samples with ChIP-chip or ChIP-seq datasets [28–30]. We find that a minimum of three biological replicates for each treatment is required for robust statistical analysis of the dataset. Biological replicates can be grown on separate plates or in separate trays and treated, harvested, and processed simultaneously. This strategy eliminates subtle differences in growth conditions that may impact gene expression. The example presented below is a microarray analysis of three biological replicates of pooled dex/cyc- and cyc-treated seedlings containing a transcription factor GR-fusion.

Amplify 50 ng of RNA extracted from pooled treated (dex/cyc and cyc) seedlings using Nugen’s Ovation RNA Amplification System V2, following the protocol exactly (see Notes 17–19).

Send 3.75 μg of amplified RNA to a microarray core facility for hybridization to Affymetrix ATH1 microarrays according to the Affymetrix GeneChip Expression Analysis Technical Manual.

Process the .CEL files obtained from the core facility using R as described below.

Open R version 2.14.1.

Click File -> Change Dir. Select the directory containing your .CEL files.

-

Download the required Bioconductor [41] packages using the following R commands:

>source(“http://www.bioconductor.org/biocLite.R”)

>biocLite(“simpleaffy”)

>biocLite(“affy”)

>biocLite(“simpleaffy”)

>biocLite(“limma”)

>biocLite(“ath1121501.db”)

>biocLite(“annotate”)

-

Load the packages into R for use.

>library(simpleaffy)

>library(affy)

>library(limma)

>library(ath1121501.db)

>library(annotate)

-

Read in the .CEL files.

>cel.files=list.files(pattern=“.CEL”) (see Note 20)

>data=ReadAffy(filenames=cel.files)

-

Perform quality control using the following commands. Ensure that no red symbols are present in the plot (see Note 21).

>qc.data=qc(data)

>plot(qc.data)

-

Normalize the data using gcrma.

>data.gcrma=gcrma(data, fast=F)

>data.gcrma.exprs=exprs(data.gcrma)

-

Generate MAS5.0 expression values and Present (P)/Marginal(M)/Absent(A) calls to be used for nonspecific filtering.

>data.mas5=mas5(data)

>data.pma=mas5calls(data)

-

Combine GCRMA intensities, P/M/A calls and MAS5.0 expression values in one data frame.

>my_frame = data.frame(exprs(data.gcrma),exprs(data.pma), exprs(data.mas5))

-

Perform nonspecific filtering to remove probesets that are called “Absent” in all six arrays.

>data.pma.exprs=exprs(data.pma)

>index.6arrays=grep(“CW”,colnames(data.pma.exprs)) (see Note 22)

>numP=apply(data.pma.exprs[,index.6arrays]==“P”,1,sum)

>gene.select=which(numP !=0)

>data.wk=data.gcrma.exprs[gene.select,]

-

Identify differentially expressed genes using LIMMA [42].

>limdes=model.matrix(~c(1,1,1,0,0,0))

>f1=lmFit(data.wk,limdes)

>ef1=eBayes(f1)

-

Adjust for multiple testing using the Benjamini–Hochberg method [43] and report the results. The file “MyResultsDexCyc_Cyc.txt” is saved in the current folder and contains the AGI gene identifier, probeset id, log fold change, p-value, and adjusted p-value. This file can be explored using Excel or any text editor.

>myt=topTable(ef1,2,n=nrow(data.wk), adjust=“BH”)

>alln=myt[,1]

>allacc=lookUp(alln, “ath1121501”, “ACCNUM”)

>allaccv=unlist(allacc)

>all(alln==names(allaccv))

>myt2=myt

>rownames(myt2)=as.character(allaccv)

>myt2=cbind(accnum=as.character(allaccv), myt)

>write.table(myt2, file=“MyResultsDexCyc_Cyc.txt”, sep=“\t”, col.names=NA)

A random subset of the significantly differentially expressed genes should be validated using RNA samples derived from an independent set of dex treatments to assess reproducibility.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by IOS grant 1257111 to D.W, JSPS postdoctoral fellowships for research abroad to N.Y., NIH Developmental Biology Training Grant T32-HD007516 and NIH Ruth L. Kirschstein NRSA F32 Fellowship GM106690-01 to C.M.W., and Science Foundation Ireland to F.W.

Footnotes

Add dexamethasone and/or cycloheximide to medium after autoclaving, when temperature is lower than 65 °C.

The rat GR coding sequence can be obtained from vector pBI-GR [14] or a subclone in pBS (pBS-GR; OHIO stock center number CD3-444).

Most chimeric proteins were created by a translational C-terminal fusion of the hormone binding domain (aa 508–795) of GR to the protein of interest [9, 14, 16], but N-terminal fusion has also been used [26].

If the mutant is sterile, transform the heterozygous mutant line.

Dex and cyc dilution needs to be freshly prepared just before treatment.

Wipe or wash tweezers and change gloves when you harvest different treatment tissues to avoid contamination.

Tissues can be stored at −80 °C for more than 3 months.

To transplant, pluck plants out of the agar with tweezers without losing the roots. Move the plants to agar with dex and/or cyc, close the lids, and grow the plants until harvesting. If contamination of plates is a persistent problem, the sucrose concentration can be reduced or removed. All processes need to be done in a sterile hood to avoid contamination.

When applying dex by spraying, it is important to achieve consistent and uniform coverage. Failure to apply dex properly can lead to inconsistent results.

Prolonged use of Silwet L-77 negatively affects plant growth. For treatment durations of more than 10 days, use a Silwet L-77 concentration of less than 0.015 % or omit the surfactant from the dex solution.

The protein synthesis block by cyc lasts only ca. 6 h based on our results using the hsp18.2 promoter driving beta-glucuronidase [44]. Successful cyc treatment will abolish GUS activity, but not GUS mRNA induction. A GFP fusion protein has also been used to test the effect of cyc [23]. Since prolonged exposure to cyc adversely affects cell viability, treatments for longer than 8 h are not advised.

Clumped tissue will not lyse properly and will therefore result in a lower yield of DNA.

The yield of total RNA from flowers, leaves, stems, and roots was approximately 1,000, 500, 500, and 300 μg/g tissue, respectively. 50–100 mg of tissues usually suffices to obtain enough RNA for analysis by RT-PCR.

Expect white pellets.

To confirm that the primer sets amplify a single fragment of the correct size it is recommended to run the qPCR product on an agarose gel.

Ensure expression of your control (housekeeping) gene does not change with treatment. The eukaryotic initiation factor EIF4A (At3g13920), ACTIN2 (At3g18780), UBIQUITIN10 (At4g05320), and the TA3 retrotransposon (At1g37110) are often used as negative control genes.

Do an extra elution in case yields are marginal. 3.75 μg is needed as input for array hybridization. Use a new 100 % EtOH bottle to make wash buffers, and keep samples very cold using a chilled heat block.

Mock treatment is water plus an amount of solvent (DMSO or EtOH) equivalent to the amount added for the dexamethasone treatment.

Dex or dex/cyc treatments of 1–4 h are recommended for identification of direct targets.

R is case-sensitive. Check that the filename extension on your CEL files is “.CEL” and not “.cel.”

We recommend reading the documentation for the simpleaffy Bioconductor package (http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/vignettes/simpleaffy/inst/doc/simple-Affy.pdf) for full interpretation of the plot. There are also many other Bioconductor packages available for exploring data quality. These are reviewed in Bolstad et al. [45].

For the grep command to work, CEL files should be named with a common identifier (e.g., “CW_dexcyc1.CEL”, “CW_dexcyc2.CEL”).

References

- 1.Locker J. Transcription factors. Academic; San Diego: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zuo J, Niu Q, Chua NH. Technical advance: an estrogen receptor-based transactivator XVE mediates highly inducible gene expression in transgenic plant. Plant J. 2000;24:265–273. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim YS, Kim SG, Lee M, Lee I, Park HY, Seo PJ, Jung JH, Kwon EJ, Suh SW, Paek KH, Park CM. HD-ZIPIII activity is modulated by competitive inhibitors via a feedback loop in Arabidopsis shoot apical meristem development. Plant Cell. 2008;20:920–933. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.057448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu C, Chen H, Er HL, Soo HM, Kumar PP, Han JH, Liou YC, Yu H. Direct interaction of AGL24 and SOC1 integrates flowering signals in Arabidopsis. Development. 2008;135:1481–1491. doi: 10.1242/dev.020255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun B, Xu Y, Ng KH, Ito T. A timing mechanism for stem cell maintenance and differentiation in Arabidopsis floral meristem. Gene Dev. 2009;23:1791–1804. doi: 10.1101/gad.1800409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roslan HA, Salter MG, Wood CD, White MR, Croft KP, Robson F, Coupland G, Doonan J, Laufs P, Tomsett AB, Caddick MX. Characterization of the ethanol-inducible alc gene-expression system in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2001;28:225–235. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.01146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muller B, Sheen J. Cytokinin and auxin interaction in root stem-cell specification during early embryogenesis. Nature. 2008;453:1094–1097. doi: 10.1038/nature06943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dalman FC, Scherrer LC, Taylor LP, Akil H, Pratt WB. Localization of the 90 kDa heat shock protein-binding site within the hormone-binding domain of the glucocorticoid receptor by peptide competition. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:3482–3490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sablowski RWM, Meyerowitz EM. A homolog of NO APICAL MERISTEM is an immediate target of the floral homeotic genes APETALA3/PISTILLATA. Cell. 1998;92:93–103. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80902-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Craft J, Samalova M, Baroux C, Townley H, Martinez A, Jepson I, Tsiantis M, Moore I. New pOP/LhG4 vectors for stringent glucocorticoid-dependent transgene expression in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2005;41:899–918. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reddy GV, Meyerowitz EM. Stem-cell homeostasis and growth dynamics can be uncoupled in the Arabidopsis shoot apex. Science. 2005;310:663–667. doi: 10.1126/science.1116261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wielopolska A, Townley H, Moore I, Waterhouse P, Helliwell C. A high-thoroughput inducible RNAi vector for plants. Plant Biotechnol J. 2005;3:583–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2005.00149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Samalova M, Brzobohaty B, Moore I. pOP6/LhGR: a stringently regulated and highly responsive dexamethasone-inducible gene expression system for tobacco. Plant J. 2005;41:919–935. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lloyd AM, Schena M, Walbot V, Davis R. Epidermal cell fate determination in Arabidopsis: patterns defined by a steroid-inducible regulator. Science. 1994;266:436–439. doi: 10.1126/science.7939683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aoyama T, Chua NH. A glucocorticoid-mediated transcriptional induction system in transgenic plants. Plant J. 1997;11:605–612. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1997.11030605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wagner D, Sablowski RWM, Meyerowitz EM. Transcriptional activation of APETALA1 by LEAFY. Science. 1999;285:582–583. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5427.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schena M, Lloyd AM, Davis RW. A steroid-inducible gene expression system for plant cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;101:1775–1780. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.23.10421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schlereth A, Moller B, Liu W, Kientz M, Flipse J, Rademacher EH, Schmid M, Jurgens G, Weijers D. MONOPTEROS controls embryonic root initiation by regulating a mobile transcription factor. Nature. 2010;464:913–916. doi: 10.1038/nature08836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.William DA, Su Y, Smith MR, Lu M, Baldwin DA, Wagner D. Genomic identification of direct target genes of LEAFY. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:1775–1780. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307842100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ito T, Ng KH, Lim TS, Yu H, Meyerowitz EM. The homeotic protein AGAMOUS controls late stamen development by regulating a jasmonate biosynthetic gene in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19:3516–3529. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.055467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ito T, Wellmer F, Yu H, Das P, Ito N, Alves-Ferreira M, Riechmann JL, Meyerowitz EM. The homeotic protein AGAMOUS controls microsporogenesis by regulation of SPOROCYTELESS. Nature. 2004;430:356–360. doi: 10.1038/nature02733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leibfried A, To JPC, Busch W, Stehling S, Kehle A, Demar M, Kieber JJ, Lohmann JU. WUSCHEL controls meristem function by direct regulation of cytokinin-inducible response regulators. Nature. 2005;438:1172–1175. doi: 10.1038/nature04270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levesque MP, Vernoux T, Busch W, Cui H, Wang JY, Blilou I, Hassan H, Nakajima K, Matsumoto N, Lohmann JU, Scheres B, Benfey PN. Whole-genome analysis of the SHOOT-ROOT developmental pathway in Arabidopsis. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e249. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang D, Amornsiripanitch N, Dong X. A genomic approach to identify regulatory nodes in the transcriptional network required resistance in plants. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e123. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okushima Y, Fukaki H, Onoda M, Theologis A, Tasaka M. ARF7 and ARF19 regulate lateral root formation via direct activation of LBD/ASL genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19:118–130. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.047761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wenkel S, Emery J, Hou B-H, Evans MMS, Barton MK. A feedback regulatory module formed by LITTLE ZIPPER and HD-ZIPIII genes. Plant Cell. 2007;19:3379–3390. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.055772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zentella R, Zhang ZL, Park M, Thomas SG, Endo A, Murase K, Fleet CM, Jikumaru Y, Nambara E, Kamiya Y, Sun TP. Global analysis of della direct targets in early gibberellin signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19:3037–3057. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.054999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaufmann K, Wellmer F, Muino JM, Ferrier T, Wuest SE, Kumar V, Serrano-Mislata A, Madueno F, Krajewski P, Meyerowitz EM, et al. Orchestration of floral initiation by APETALA1. Science. 2010;328:85–89. doi: 10.1126/science.1185244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sozzani R, Cui H, Moreno-Risueno MA, Busch W, Van Norman JM, Vernoux T, Brady SM, Dewitte W, Murray JA, Benfey PN. Spatiotemporal regulation of cell-cycle genes by SHORTROOT links patterning and growth. Nature. 2010;466:128–132. doi: 10.1038/nature09143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Winter CM, Austin RS, Blanvillain-Baufume S, Reback MA, Monniaux M, Wu MF, Sang Y, Yamaguchi A, Yamaguchi N, Parker JE, et al. LEAFY target genes reveal floral regulatory logic, cis motifs, and a link to biotic stimulus response. Dev Cell. 2011;20:430–443. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang W, Perez-Garcia P, Pokhilko A, Millar AJ, Antoshechkin I, Riechmann JL, Mas P. Mapping the core of the Arabidopsis circadian clock defines the network structure of the oscillator. Science. 2012;336:75–79. doi: 10.1126/science.1219075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reinhart BJ, Liu T, Newell NR, Magnani E, Huang T, Kerstetter R, Michaels S, Barton MK. Establishing a framework for the Ad/abaxial regulatory network of Arabidopsis: ascertaining targets of class III homeodomain leucine zipper and KANADI regulation. Plant Cell. 2013;25:3228–3249. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.111518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eklund M, Staldal V, Valsecchi I, Clerlik I, Eriksson C, Hiratsu K, Ohme-Takagi M, Sunstrom JF, Thelander M, Ezcurra I, Sundberg E. The Arabidopsis thaliana STYLISH1 protein acts as a transcriptional activator regulating auxin biosynthesis. Plant Cell. 2010;22:349–363. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.064816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Franck A, Guilley H, Jonard G, Richards K, Hirth L. Nucleotide sequence of cauliflower mosaic virus DNA. Cell. 1980;21:285–294. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90136-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brand U, Grunewald M, Hobe M, Simon R. Regulation of CLV3 expression by two homeobox genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2002;129:565–575. doi: 10.1104/pp.001867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cole M, Chandler J, Weijers D, Jacobs B, Comelli P, Werr W. DORNROSCHEN is a direct target of the auxin response factor MONOPTEROS in the Arabidopsis embryo. Development. 2009;136:1643–1651. doi: 10.1242/dev.032177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clough SJ, Bent AF. Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998;16:735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wagner D, Meyerowitz EM. Switching on flowers: transient LEAFY induction reveals novel aspects of the regulation of reproductive development in Arabidopsis. Front Plant Sci. 2011;2:60. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2011.00060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamaguchi N, Winter C, Wu M-F, Kanno Y, Yamaguchi A, Seo M, Wagner D. Gibberellin acts positively then negatively to control onset of flower formation in Arabidopsis. Science. 2014;344:638–664. doi: 10.1126/science.1250498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamaguchi N, Wu M-F, Winter C, Berns M, Nole-Wilson S, Yamaguchi A, Coupland G, Krizek B, Wagner D. A molecular framework for auxin-mediated initiation of floral primordia. Dev Cell. 2013;24:271–282. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reimers M, Carey VJ. Bioconductor: an open source framework for bioinformatics and computational biology. Methods Enzymol. 2006;411:119–134. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)11008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smyth G. Linear models and empirical Bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2004;3 doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1027. Article 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wagner D, Sablowski RW. Glucocorticoid fusions for transcription factor. In: Weigel D, Glazebrook J, editors. Arabidopsis—a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bolstad BM, Collin F, Brettschneider J, Simpson K, Cope L, Irizarry RA, Speed TP. Quality assessment of Affymetrix GeneChip data. In: Gentleman R, Carey V, Huber W, Irizarry R, Dudoit S, editors. Bioinformatics and computational biology solutions using R and bioconductor, statistics for biology and health. Springer; New York: 2005. pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]