SUMMARY

Cerebral cavernous malformations (CCMs) are a cause of stroke and seizure for which no medical therapies exist. CCMs arise from loss of an adaptor complex that negatively regulates MEKK3-KLF2/4 signaling in brain endothelial cells, but upstream activators of this disease pathway remain unknown. Here, we identify endothelial TLR4 and the gut microbiome as critical stimulants of CCM formation. Activation of TLR4 by gram negative bacteria or lipopolysaccharide accelerates CCM formation, while genetic or pharmacologic blockade of TLR4 signaling prevents CCM formation in mice. Polymorphisms that increase expression of TLR4 or its co-receptor CD14 are associated with higher CCM lesion burden in humans. Germ-free mice are protected from CCM formation, and a single course of antibiotics permanently alters CCM susceptibility in mice. These studies identify unexpected roles for the microbiome and innate immune signaling in the pathogenesis of a cerebrovascular disease, as well as novel strategies for its treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Cerebral cavernous malformations (CCMs) are relatively common vascular malformations that arise predominantly in the central nervous system, causing hemorrhagic stroke and seizure1. CCMs arise from loss of function mutations in three genes, KRIT1, CCM2, and PDCD10, that encode components of a heterotrimeric, intracellular adaptor protein complex (the “CCM complex”)2,3. The clinical course of familial CCM disease is highly variable, even among individuals who share identical germline mutations4–6, suggesting the existence of powerful genetic and/or environmental disease modifiers. Present treatment for CCMs consists solely of palliative therapies or neurosurgical resection.

Recent studies of vertebrate genetic models and human CCM lesions have demonstrated that loss of the CCM complex results in vascular lesion formation due to increased MEKK3-KLF2/4 signaling in brain endothelial cells7–10, and that the CCM complex suppresses MEKK3-KLF2/4 signaling through a direct interaction between CCM2 and MEKK311,12. Since effective drugs targeting the MEKK3-KLF2/4 pathway do not exist, these molecular insights have not had an immediate translational impact. However, they raise a key mechanistic question: if the role of the CCM complex is to negatively regulate MEKK3-KLF2/4 signaling, what activates this pathway in brain endothelial cells? Identification of upstream activators of this pathway is needed to understand the pathogenesis of CCM disease and reveal viable therapeutic strategies.

RESULTS

CCM formation is driven by gram negative bacteria and lipopolysaccharide

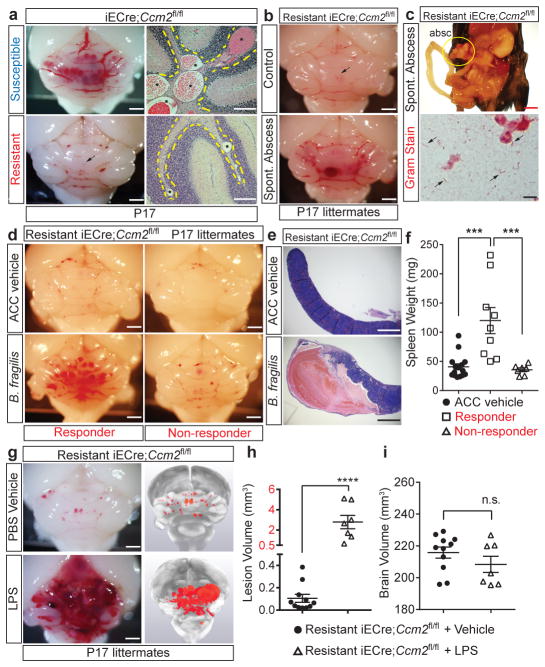

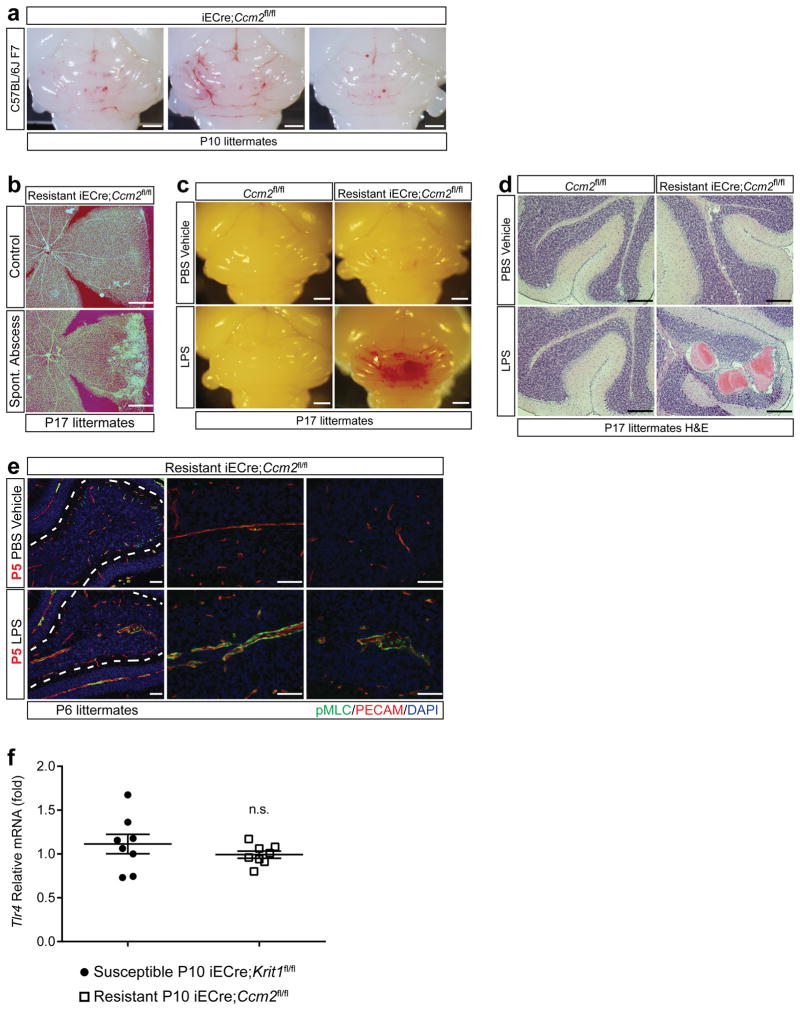

To investigate CCM formation in mice, we generated animals in which endothelial specific deletion of Krit1 or Ccm2 was induced one day after birth (P1, iECre;Krit1fl/fl & iECre;Ccm2fl/fl). In this model, vascular malformations first appear in the cerebellar white matter at P6, with numerous mature lesions present by P109,13. These mice were maintained as inbred breeding colonies and initially demonstrated a highly penetrant lesion phenotype (termed “susceptible”, Fig. 1a top). However, following a change in vivarium at the University of Pennsylvania, we noted the spontaneous emergence of iECre;Krit1fl/fl & iECre;Ccm2fl/fl sub-colonies that developed barely visible hindbrain lesions at P17 (termed “resistant”, Fig. 1a bottom). Previous studies have demonstrated high CCM penetrance on a C57BL/6J background13, but iECre;Ccm2fl/fl animals back-crossed seven generations to C57BL/6J remained resistant to CCM formation (Extended Data Fig. 1a). Significantly, among a large population of CCM-resistant animals, we detected a small number of individual pups that exhibited robust CCM formation in association with the presence of intra-abdominal, gram negative bacterial (GNB) abscesses that likely developed following tamoxifen injection (Fig. 1b, c and Extended Data Fig. 1b). This observation suggested that gram negative infection accelerates CCM pathogenesis.

Figure 1. CCM formation is stimulated by gram negative bacterial infection and intravenous LPS injection.

a, Lesion formation in susceptible and resistant iECre;Ccm2fl/fl mice at P17. Dotted lines trace cerebellar white matter. Asterisks; CCM lesions Scale bars, 1 mm (left) and 100 μm (right). b, Hindbrains of resistant iECre;Ccm2fl/fl littermates without (top) and with (bottom) spontaneous abdominal gram negative abscess. Scale bars, 1 mm. Arrows; CCM lesions. c, The bacterial abscess (“absc”) identified in (b) contains gram negative bacteria (arrows). Scale bars, 4 mm (top) and 10μm (bottom). d, CCM formation in resistant iECre;Ccm2fl/fl littermates following injection with a live B. fragilis/autoclaved cecal contents mixture (B. fragilis) or ACC alone (ACC vehicle). Scale bars, 1 mm. e–f, Resistant iECre;Ccm2fl/fl responders exhibit splenic abscesses and increased spleen weight compared with non-responders. g, CCM formation in resistant iECre;Ccm2fl/fl mice following vehicle or LPS treatment. Scale bars, 1 mm. h–i, Quantitation of lesion and total brain volumes. Error bars shown as s.e.m. and significance determined by one way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak correction for multiple comparisons or unpaired, two-tailed t-test. **** indicates p<0.0001; ***indicates p<0.001; n.s. indicates p>0.05.

To directly test the role of gram negative infection, gram negative abscesses were induced in resistant iECre;Ccm2fl/fl mice at P5 by intra-peritoneal injection of live Bacteroides fragilis (B. frag). Following B. frag injection, 9/16 resistant iECre;Ccm2fl/fl animals developed large CCM lesions (termed “Responders”, Fig. 1d, left), but 7/16 animals did not (termed “Non-responders”, Fig. 1d, right). Responders to B. frag injection exhibited splenic abscesses and higher spleen weights compared with non-responders (Fig. 1e, f), suggesting that hematogenous spread of GNB from the site of abscess was required to stimulate CCM formation in resistant iECre;Ccm2fl/fl animals. Since GNB stimulate mammalian cellular responses in large part through cell membrane-derived lipopolysaccharide (LPS), we tested the sufficiency of LPS to drive CCM formation. Injection of LPS resulted in the formation of massive lesions in resistant iECre;Ccm2fl/fl animals (Fig. 1g–i), but had no effect on Ccm2fl/fl littermates (Extended Data Fig. 1c, d). These findings reveal that blood-borne GNB and LPS are strong drivers of CCM formation in mice.

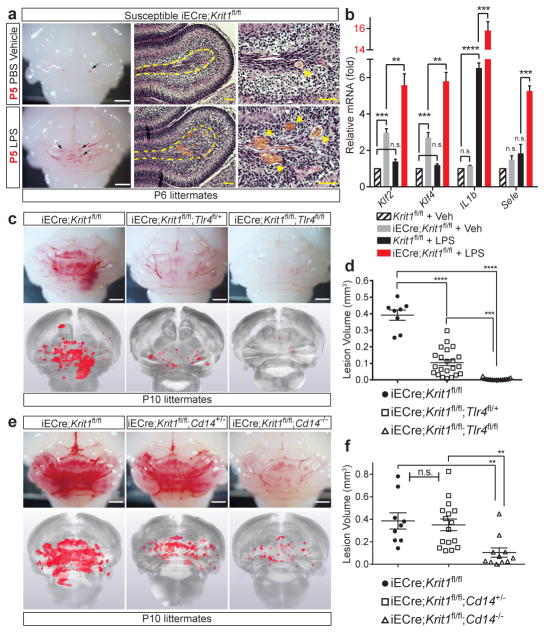

Endothelial TLR4 function and brain endothelial CCM complex deficiency underlie lesion formation

We recently demonstrated that loss of the CCM proteins KRIT1 or CCM2 results in vascular malformation due to increased MEKK3 signaling in endothelial cells9. LPS activates intracellular signals through the innate immune receptor TLR414, and MEKK3-deficient fibroblasts are unable to activate downstream signaling responses to LPS in vitro15. We therefore hypothesized that GNB and LPS accelerate CCM formation by activating TLR4-MEKK3-KLF2/4 signaling in CCM complex-deficient brain endothelial cells. Analysis of susceptible iECre;Krit1fl/fl mice revealed that CCM lesions arise in the absence of an immune cell infiltrate at P6 (Extended Data Fig. 2), and that a single dose of LPS at P5 accelerated CCM formation by P6 (Fig. 2a). Consistent with a brain endothelial cell intrinsic mechanism, we observed synergistic effects of CCM complex-deficiency and LPS injection on the expression of CCM-causing genes Klf2 and Klf4, known endothelial TLR4 signaling targets IL-1β (Il1b) and E-selectin (Sele), as well as on the level of phospho-myosin light chain (Fig. 2b and Extended Data Fig. 1e).

Figure 2. CCM lesion formation requires endothelial TLR4/CD14 signaling.

a, Injection of LPS at P5 drives CCM formation by P6 in susceptible iECre;Krit1fl/fl littermates. Scale bars, 1mm (white) and 50 μm (yellow). Arrows and arrowheads; CCM lesions. Dotted lines; cerebellar white matter. b, Gene expression in cerebellar endothelial cells isolated from the indicated littermates at P6. N≥3 per group. c–f, Genetic rescue of CCM formation with endothelial loss of TLR4 or global loss of CD14. Visual appearance of CCM lesions (above), corresponding microCT images (below), and lesion volume quantitation. Scale bars, 1mm. Error bars shown as s.e.m and significance determined by one-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak correction for multiple comparisons. ****indicates p<0.0001; ***indicates p<0.001; **indicates p<0.01; n.s. indicates p>0.05.

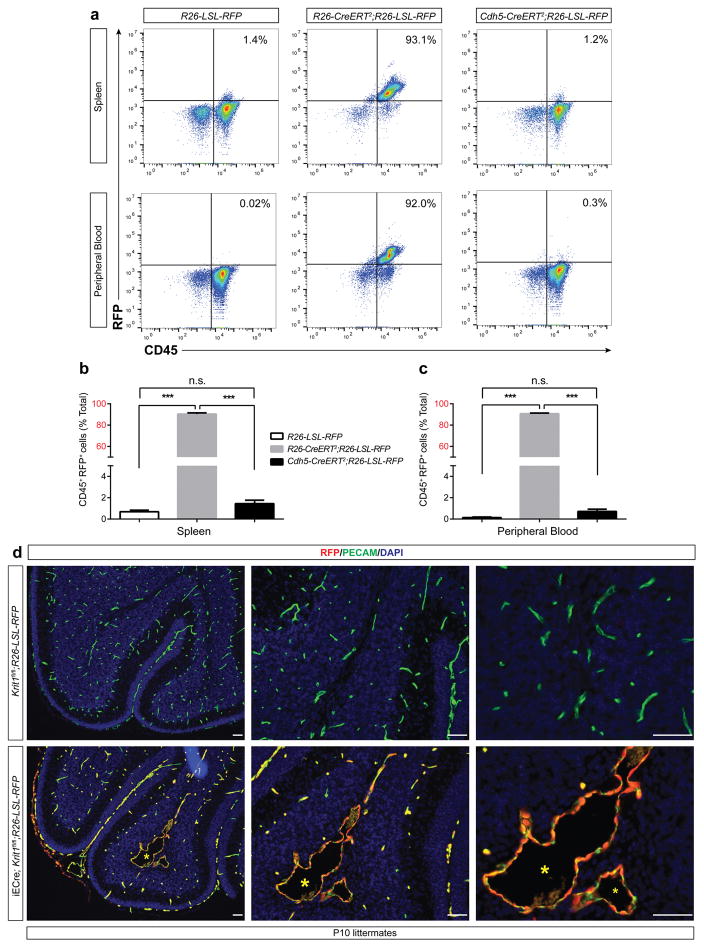

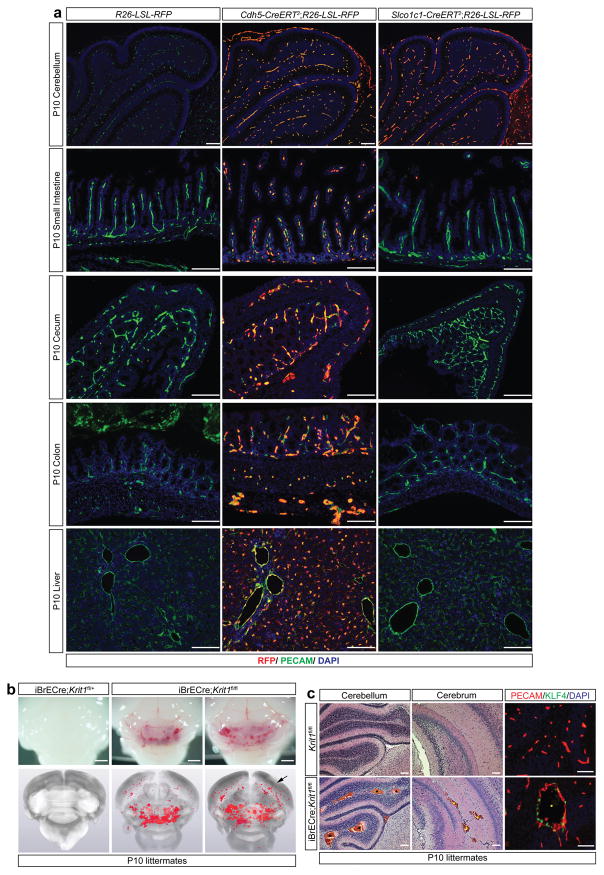

To directly test the requirement for endothelial TLR4 in spontaneous CCM formation, we bred iECre;Krit1fl/fl;Tlr4fl/+ and iECre;Krit1fl/fl;Tlr4fl/fl mice using animals from the susceptible iECre;Krit1fl/fl colony. Loss of a single endothelial Tlr4 allele resulted in an approximately 75% reduction in CCM lesion burden at P10, while loss of both resulted in virtually complete prevention of CCM lesion formation (Fig. 2c, d and Extended Data Fig. 3a). Cd14 encodes a soluble TLR4 co-receptor that binds LPS and facilitates TLR4 signaling16,17. Although less complete, global loss of CD14 also prevented CCM formation in susceptible iECre;Krit1fl/fl mice (Fig. 2e, f and Extended Data Fig. 3b). Lineage tracing studies confirmed that iECre (Cdh5(PAC)-CreERT2) transgene activity was restricted to endothelial cells (Extended Data Fig. 4), excluding a requirement for hematopoietic cell TLR4 signaling during CCM formation. Finally, to exclude a role for the CCM complex in endothelial cells outside the brain, we used a recently generated Slco1c1(BAC)-CreERT2 transgene18 to further restrict deletion of Krit1 to brain endothelial cells. Slco1c1(BAC)-CreERT2;R26-LSL-RFP animals exhibited RFP+ endothelial cells in the brain but not in the gut or liver (Extended Data Fig. 5a), and Slco1c1(BAC)-CreERT2;Krit1fl/fl (“iBrECre Krit1fl/fl”) animals developed CCM lesions like those in iECre;Krit1fl/fl animals (Extended Data Fig. 5b, c). These genetic findings identify endothelial TLR4 signaling as a critical driver of CCM formation in mice.

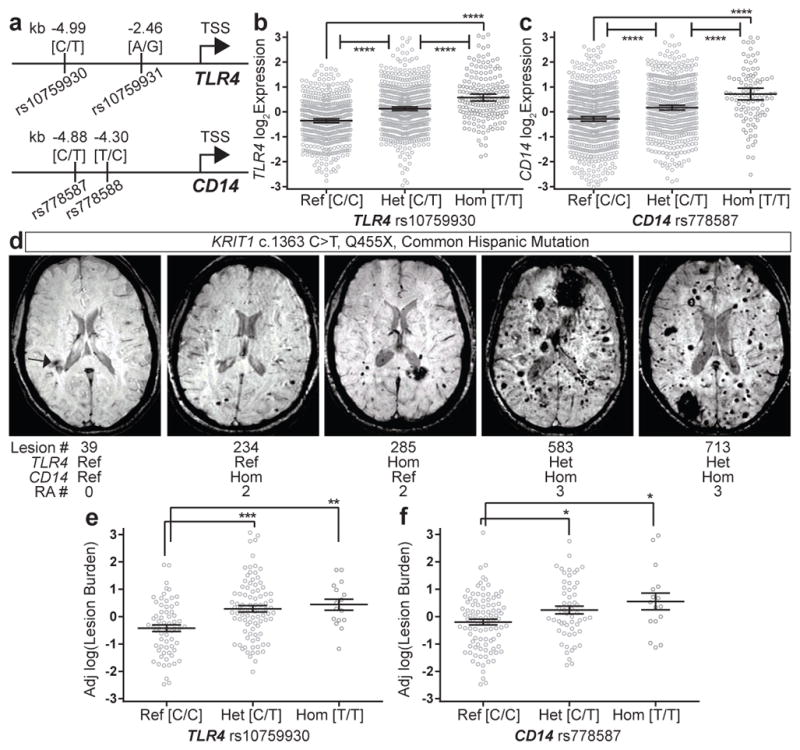

Polymorphisms that increase TLR4 and CD14 expression are associated with increased CCM lesion formation in humans

Human and mouse studies have demonstrated that TLR4 signaling positively correlates with receptor expression levels19,20, suggesting that polymorphisms associated with changes in TLR4 expression might influence the natural history of human CCM disease. We recently analyzed 830 genetic variants of 56 inflammatory and immune related genes in 188 human patients with an identical nonsense mutation in the KRIT1 gene (Q455X) in whom CCM lesion burden was measured using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)6. Following statistical analysis, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in only two genes, TLR4 (rs10759930, chromosome 9, Fig. 3a) and CD14 (rs778587, chromosome 5, Fig. 3a), were found to be significantly associated with increased CCM lesion number. Further analysis of genes in TLR4-MEKK3-KLF2/4 signaling pathways identified additional SNPs for TLR4 (rs10759931) and CD14 (rs778588) in linkage disequilibrium with those previously identified (Fig. 3a), but none in other pathway genes (Materials and Methods) that associated with altered lesion burden. Significantly, the TLR4 and CD14 SNPs associated with increased CCM lesion number are in the 5′ genomic region of each gene (Fig. 3a), and constitute cis expression quantitative trait loci (cis-eQTLs) that positively regulate whole-blood cell expression of TLR4 and CD14 in a dose-dependent manner corresponding with risk allele number (Fig. 3b–c and21,22). These results were independently corroborated by a similar GTEx Consortium study (Materials and Methods). MRI analysis revealed additive CCM lesion numbers in KRIT1 Q455X patients who carried one, two or three TLR4 or CD14 risk alleles (Fig. 3d–f). Carriers of TLR4 or CD14 risk alleles were associated with 72% or 49% more lesions compared to wildtype individuals, respectively (Fig. 3e and f). These findings demonstrate that genetic changes associated with altered TLR4 and CD14 expression result in coordinate changes in CCM lesion formation in both humans and mice (Fig. 2c–f), supporting the hypothesis that TLR4/CD14 signaling plays a central and conserved role in CCM pathogenesis.

Figure 3. Increased TLR4 or CD14 expression is associated with higher lesion number in familial CCM patients.

a, SNPs in the 5′ genomic regions of TLR4 and CD14 associated with increased lesion numbers in familial CCM patients are shown relative to the transcriptional start site (TSS). b–c, Normalized microarray measurement of TLR4 and CD14 expression in whole blood cells from individuals in the general population with the indicated TLR4 rs10759930 and CD14 rs778587 genotypes. d, Representative MRI images of KRIT1 Q455X patients with raw lesion count and TLR4/CD14 SNP genotypes (RA; risk allele). e–f, Sex and age adjusted log(lesion burden) in KRIT1 Q455X patients with indicated genotypes. Error bars shown as 95% confidence intervals and significance determined by one-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak correction for multiple comparisons. ****indicates p<0.0001; ***indicates p<0.001; **indicates p<0.01; *indicates p<0.05.

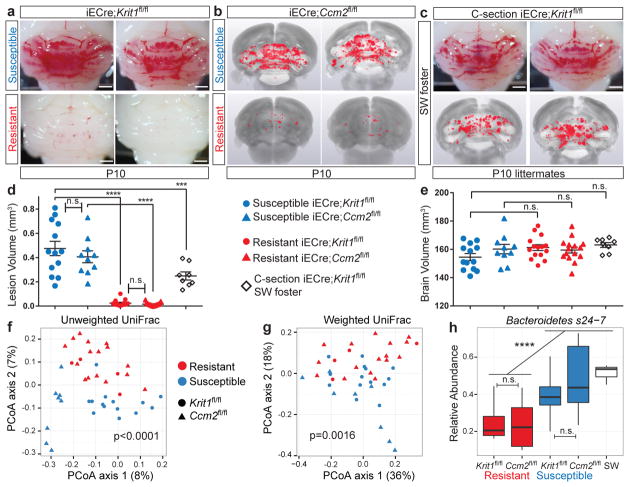

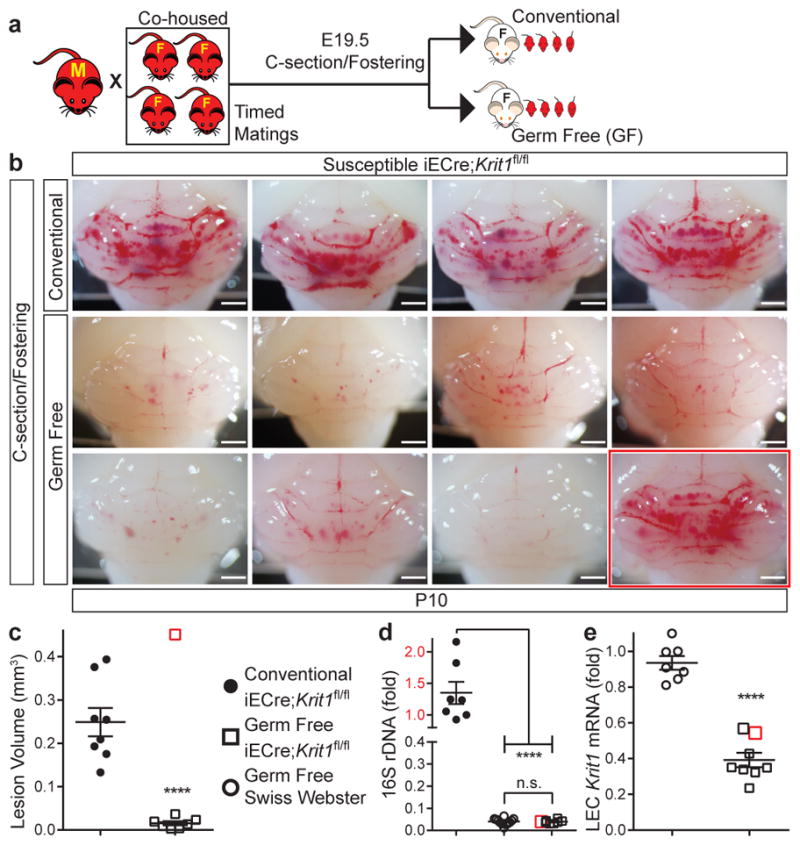

The bacterial microbiome is a primary driver of CCM formation in mice

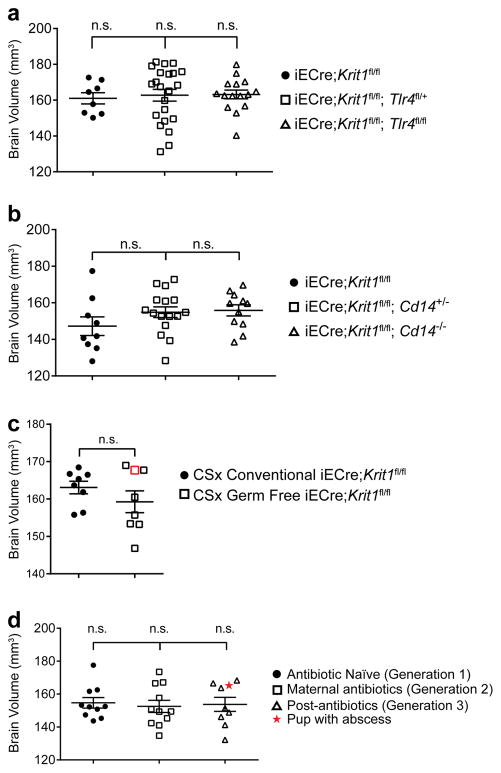

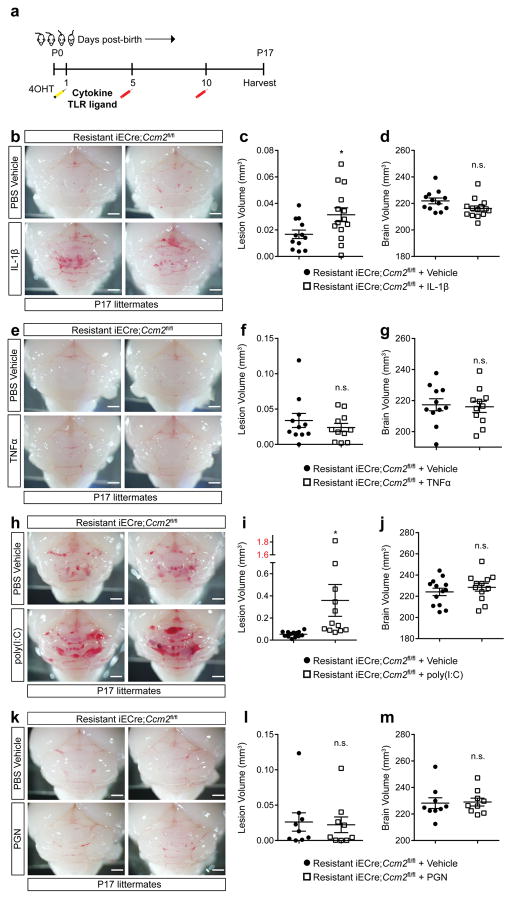

Although endogenous TLR4 ligands have been identified23, the primary known TLR4 ligand is GNB-derived LPS14,24. The findings that CCM pathogenesis requires endothelial TLR4 and CD14 (Fig. 2c–f) and that CCM susceptibility shifted dramatically with a change in vivarium (Fig. 1a) suggested that GNB in the microbiome may be a primary source of TLR4 ligand and an important regulator of CCM disease. To directly test the role of the bacterial microbiome during CCM formation, we delivered susceptible E19.5 iECre;Krit1fl/fl neonates using sterile C-section and fostered them to imported conventional or germ-free Swiss Webster mothers (Fig. 4a). All fostered iECre;Krit1fl/fl neonates exhibited robust CCM formation at P10 when raised by conventional Swiss Webster mothers (Fig. 4b, c and Extended Data Fig. 3c). In contrast, 7/8 fostered iECre;Krit1fl/fl neonates raised in germ-free conditions failed to develop CCM lesions, indicating that bacteria are required for CCM pathogenesis in most animals (Fig. 4b–c and Extended Data Fig. 3c). A single fostered iECre;Krit1fl/fl neonate developed CCM lesions despite reductions in gut bacteria and Krit1 mRNA similar to fostered iECre;Krit1fl/fl littermates that failed to develop CCMs (red boxes, Fig. 4b–e and Extended Data Fig. 3c). Prior studies have demonstrated that MEKK3 is required for signaling downstream of cytokines IL-1β15 and TNFα25, and other pattern-recognition receptors can signal in endothelial cells through the same effectors utilized by TLR426,27. Thus, the generation of lesions in a germ-free iECre;Krit1fl/fl neonate suggested that cytokines or immune receptors other than TLR4 may also drive CCM formation in vivo. To directly test the ability of non-TLR4 ligands to stimulate CCM formation, we administered IL-1β, TNFα, TLR3 ligand poly(I:C), and TLR2 ligand peptidoglycan (PGN) to resistant iECre;Ccm2fl/fl neonates and assessed effects on CCM formation. IL-1β and poly(I:C) treatment significantly increased CCM lesion volume although no difference was observed with TNFα or PGN (Extended Data Fig. 6). These findings identify the bacterial biome as a critical driver of CCM formation in vivo, but also demonstrate that cytokines and innate immune ligands other than LPS can support CCM formation in vivo.

Figure 4. CCMs fail to form in most germ-free mice.

a, Experimental design in which offspring of susceptible Krit1fl/fl females were fostered to conventional or germ-free Swiss-Webster mothers. b, Hindbrains from P10 offspring fostered in conventional (4/8 shown, top) or germ-free conditions (8/8 shown, bottom). c, Lesion volume quantitation of iECre;Krit1fl/fl hindbrains following C-section/fostering in conventional or germ-free conditions. d, Relative quantitation of neonatal gut bacterial load measured by qPCR of bacterial 16S rRNA gene copies. e, Relative quantitation of Krit1 mRNA in lung endothelial cells (LEC) measured by qPCR. Red boxes indicate values for the single germ-free animal with significant lesions. Scale bars, 1 mm. Error bars shown as s.e.m. and significance determined by unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test. ****indicates p<0.0001; n.s. indicates p>0.05.

CCM susceptibility is associated with specific gram negative bacteria in the gut microbiome

Assessment of CCM formation in iECre;Krit1fl/fl and iECre;Ccm2fl/fl mice at P10 revealed a remarkably binary phenotype in which susceptible mice developed numerous lesions while resistant mice developed virtually none (Fig. 5a–b and d–e). Lesion volumes were indistinguishable among susceptible iECre;Krit1fl/fl and iECre;Ccm2fl/fl animals and no difference in brain endothelial Tlr4 expression was detected between susceptible and resistant animals (Extended Data Fig. 1f), supporting a dominant role of non-genetic factors such as the gut microbiome in determining CCM susceptibility.

Figure 5. CCM susceptibility is associated with increased levels of gram negative Bacteroidetes s24-7.

a–c, Visual and microCT images of hindbrains from susceptible (top) and resistant (bottom) iECre;Krit1fl/fl and iECre;Ccm2fl/fl animals and susceptible iECre;Krit1fl/fl animals fostered to conventional Swiss-Webster (SW) mothers. Scale bars, 1 mm. d–e, Quantitation of lesion and brain volumes. Error bars shown as s.e.m. and significance determined by one-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak correction for multiple comparisons. f–g, Principle Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) of unweighted and weighted UniFrac bacterial composition distances from the feces of susceptible and resistant Krit1fl/fl and Ccm2fl/fl mothers. P-values compare bacterial compositions in all resistant to all susceptible animals using PERMANOVA. h, Relative abundance boxplot of Bacteroidetes s24-7 in susceptible or resistant Krit1fl/fl or Ccm2fl/fl mothers and conventional SW foster mothers. Significance determined by linear mixed effects model with Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiple comparisons. ****indicates p<0.0001; ***indicates p<0.001; n.s. indicates p>0.05. Note: Conventional SW data from Figs. 4 and 5 are the same experiment.

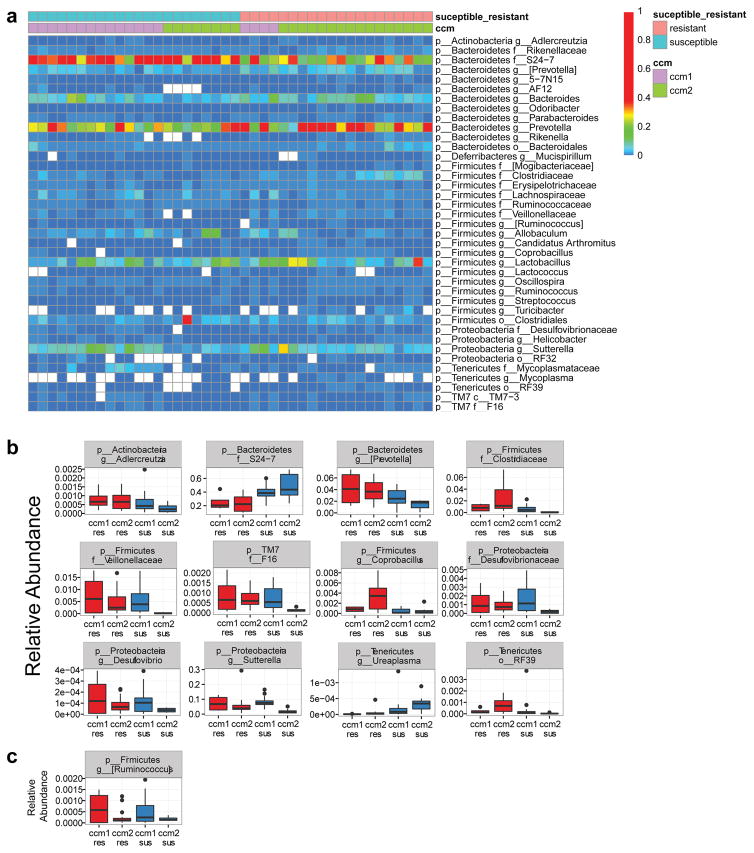

To identify specific bacteria that associate with CCM susceptibility or resistance, we performed 16S rRNA gene sequencing of bacterial DNA extracted from the feces of female mice that raised susceptible or resistant iECre;Krit1fl/fl and iECre;Ccm2fl/fl animals (Ext. Data Fig. 7a). A PERMANOVA test of unweighted UniFrac distances revealed clear separation of susceptible and resistant bacterial microbiome communities, regardless of whether they were derived from iECre;Krit1fl/fl or iECre;Ccm2fl/fl colonies (p<0.0001, R2=0.051 Fig. 5f). Further accounting for relative abundances of bacterial species, significant separation between susceptible and resistant animals was also observed using weighted UniFrac analysis (p=0.0016, R2=0.091, Fig. 5g). Fitting generalized, linear mixed effects models for commonly present bacterial taxa identified one major group that differed significantly between the gut biomes of susceptible and resistant animals: gram negative Bacteroidetes s24-7 (s24-7) was significantly more abundant in susceptible animals irrespective of genotype (Fig. 5h, Extended Data Fig. 7b–c). Significantly, 16S sequencing of gut bacteria from conventional Swiss-Webster foster mothers revealed high levels of s24-7, explaining susceptibility to CCM formation by C-section/fostered iECre;Krit1fl/fl neonates (Fig. 4 and Fig. 5c–e and h). These findings support a key role for the gut microbiome in CCM disease pathogenesis, and suggest that CCM susceptibility can be significantly affected by levels of specific GNB in the gut microbiome.

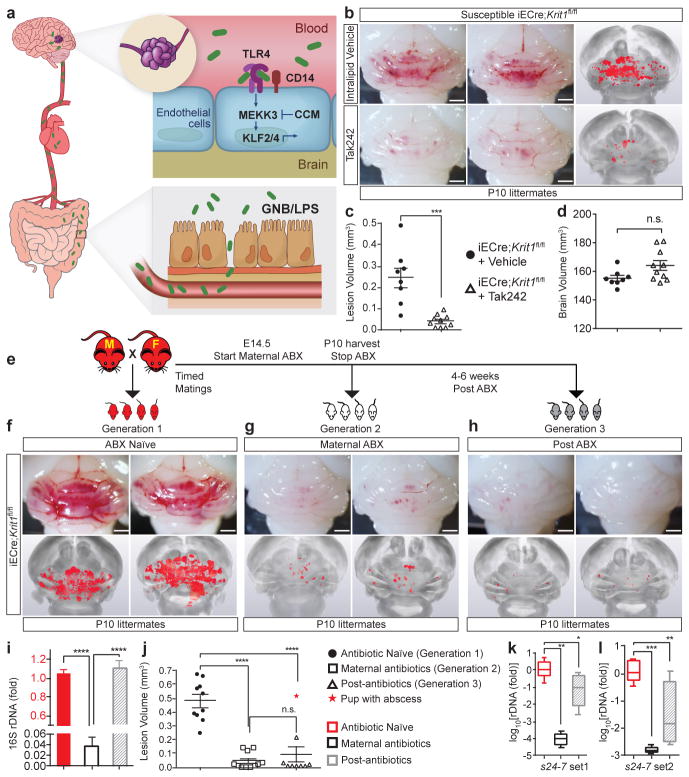

CCM formation can be blocked by TLR4 antagonists or altering the microbiome

Our studies do not exclude a role for TLR4 signaling in non-brain endothelial cells. However, they are most consistent with a disease model in which brain endothelial TLR4/CD14 receptors stimulate MEKK3-KLF2/4 signaling in response to GNB or GNB-derived LPS that translocate from the gut lumen to circulating blood (Fig. 6a)—a process significantly influenced by the composition of the gut microbiome28–31. This model predicts two novel approaches to treat CCM disease: TLR4 blockade and deliberate microbiome manipulation.

Figure 6. Preventing CCM formation by TLR4 antagonism and microbiome manipulation.

a, Model of pathogenesis in which gram negative bacteria (GNB) in the gut are the source of LPS that enters circulating blood, activating luminal, brain endothelial TLR4 receptors. LPS-TLR4 stimulation drives MEKK3-KLF2/4 signaling to induce CCMs. b, Visual and microCT images of hindbrains from vehicle or Tak242 injected animals. c–d, Lesion and brain volume quantitation. e, Intergenerational experiment in which susceptible iECre;Krit1fl/fl mating pairs were used to test the acute and chronic effects of antibiotic treatment on CCM formation. f–h, Visual and corresponding microCT images of hindbrains from offspring of three generations from one mating pair, representative of three pairs. i, Relative quantitation of neonatal gut bacterial load measured by qPCR of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene. N=4 per group. j, Lesion volume quantitation. k–l, Relative quantitation of Bacteroidetes s24-7 (s24-7) load in the neonatal gut measured by qPCR of the s24-7 rRNA gene (two distinct primer sets). N≥8 per group. All scale bars, 1 mm. Error bars shown as s.e.m. or boxplot and significance determined by one-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak correction for multiple comparisons. ****indicates p<0.0001; ***indicates p<0.001; **indicates p<0.01; *indicates p<0.05; n.s. indicates p>0.05.

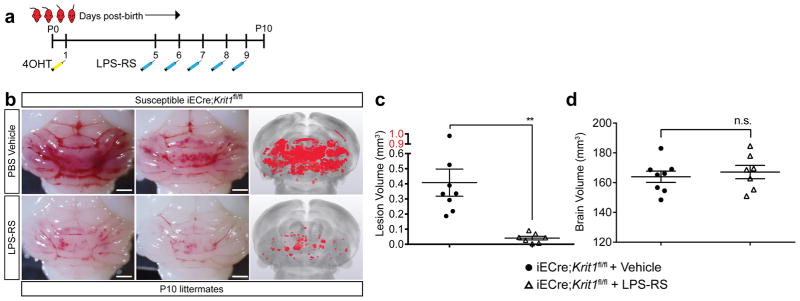

Tak242 (resatorvid) is a small molecule TLR4 antagonist that binds the intracellular domain of TLR4 and blocks signal transduction32. Treatment of susceptible iECre;Krit1fl/fl mice with Tak242 demonstrated an approximately 80% reduction in CCM lesion volume (Fig. 6b–d). LPS-RS is a hypo-acetylated LPS derived from Rhodobacter sphaeroides that competitively antagonizes TLR433. Treatment of susceptible iECre;Krit1fl/fl mice with LPS-RS conferred a >90% reduction in CCM lesion volume (Extended Data Fig. 8). These studies confirm the essential role of TLR4 signaling in CCM pathogenesis and suggest that TLR4 antagonists may be effective therapies.

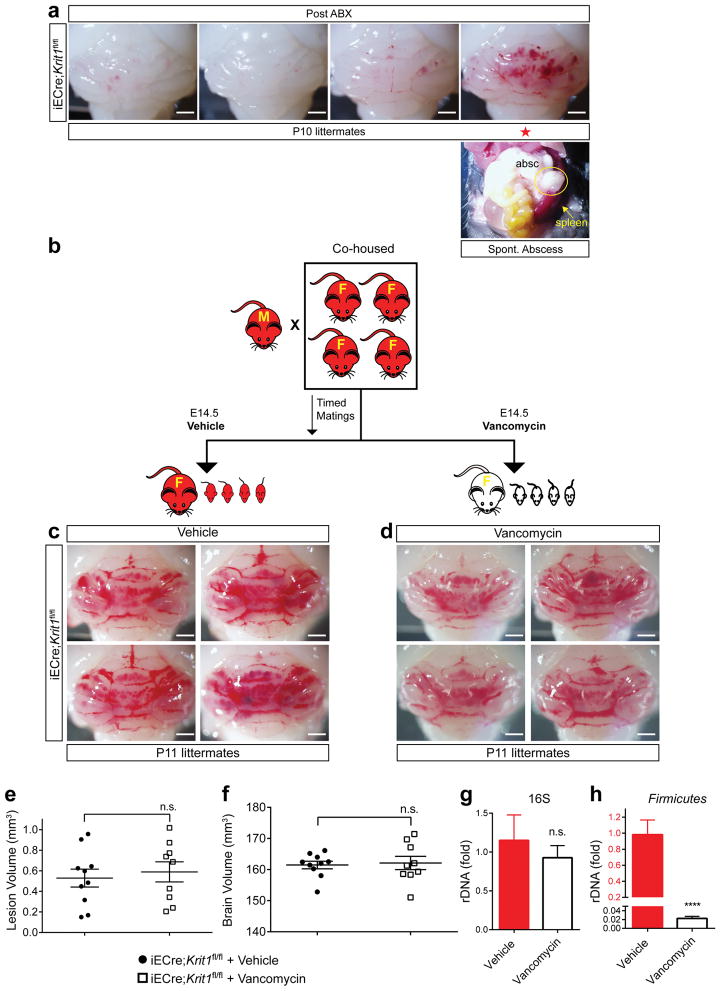

To test the effect of deliberate microbiome manipulation on CCM formation, we designed an intergenerational study utilizing a single course of antibiotics to reset the microbiome (Fig. 6e). Male-female pairs of susceptible iECre;Krit1fl/fl mice were crossed and baseline CCM formation was measured in the offspring at P10 (Fig. 6f ‘Generation 1 – ABX Naïve’). Next, the same male-female pairs were mated a second time and broad-spectrum antibiotics administered maternally from E14.5 to P10 prior to lesion assessment (Fig. 6g ‘Generation 2 – Maternal ABX’). Finally, 4–6 weeks after withdrawal of antibiotics, the same male-female pair delivered a third litter and lesions were assessed at P10 (Fig. 6h ‘Generation 3 – Post ABX’). As expected, Generation 1 susceptible iECre;Krit1fl/fl mice developed numerous lesions (Fig. 6f, j and Extended Data Fig. 3d ). Consistent with our findings using germ-free animals, Generation 2 maternal antibiotic treatment reduced CCM formation by >95% (Fig. 6g, j), in association with a 96% reduction in total gut bacterial load (Fig. 6i). Remarkably, Generation 3 iECre;Krit1fl/fl offspring from the same mating pair failed to develop CCMs (Fig. 6h, j), despite bacterial load returning to pre-antibiotic levels (Fig. 6i), except for a single Generation 3 animal that developed an intra-abdominal abscess with pronounced splenomegaly (Fig. 6j, star, Extended Data Fig. 9a). Maternal treatment with vancomycin alone, a broad-spectrum antibiotic specific for gram positive bacteria, had no effect on CCM formation, consistent with a causal role for GNB (Extended Data Fig. 9b–h). Measurement of s24-7 levels in the intestines of Generation 1, 2 and 3 neonates harvested for analysis of lesion volume revealed a significant, sustained reduction in Generation 3 relative to Generation 1 (Fig. 6k–l), consistent with the observation that resistant Krit1fl/fl and Ccm2fl/fl mothers have lower s24-7 levels than susceptible mothers (Fig. 5h). Conversely, sterile C-section/fostering of resistant iECre;Krit1fl/fl and iECre;Ccm2fl/fl pups to conventional Swiss-Webster foster mothers with high levels of s24-7 (Fig. 5h) restored CCM susceptibility (Extended Data Fig. 10). These findings provide further evidence that qualitative changes in the bacterial microbiome can alter disease course.

DISCUSSION

Designing rational therapies for CCM disease is complicated by the fact that many of the pathogenic events take place within brain endothelial cells of the central nervous system (CNS), where drug delivery is blocked by the blood-brain barrier (BBB)34. The finding that LPS accelerates CCM formation (Fig. 2a–e) although it is unable to cross the BBB35 suggests that CCM formation is driven by activation of endothelial TLR4 receptors on the luminal, blood side of the BBB (Fig. 6a). Tak242 or LPS-RS effectively reduce lesion formation, confirming endothelial TLR4 as a “druggable” target for CCM disease (Fig. 6b–d and Extended Data Fig. 8). Existing TLR4 blocking agents developed for sepsis treatment36 could potentially be repurposed as therapies for severe human CCM disease. However, such application will first need to address the requirement for chronic therapy, the potential risk of lethal sepsis, and whether anti-TLR4 therapy will affect existing as well as nascent lesions.

Manipulation of gut microbiome-host interactions is a more exciting potential strategy to treat a life-long disease such as CCM. The microbiome has been associated with many human diseases37, but specific molecular mechanisms by which it contributes to disease pathogenesis have been difficult to define. Our studies support a central role for the gut microbiome and endothelial responses to GNB in the pathogenesis of CCMs. We find that the bacterial microbiome is the primary source of TLR4 ligand required to stimulate CCM formation in mice, and that small qualitative differences in the gut microbiome may have dramatic effects on the course of CCM disease in this animal model. Although s24-7 is not found in humans, the association of CCM disease susceptibility with this GNB is particularly interesting because it is associated with disruption of the gut epithelial barrier38. Thus, a key step in CCM pathogenesis is predicted to be translocation of bacteria or bacterial LPS from the gut lumen into circulation (Fig. 6a). Whether similar inflammatory/colitogenic microbiomes also accelerate human CCM disease remains an important question. The clinical course of CCM disease is exceptionally variable, even among individuals with familial CCM disease due to a common KRIT1 mutation4,6. Genetic polymorphisms that alter TLR4 and CD14 expression account for some of this heterogeneity (Fig. 3), but most of the clinical variability remains unexplained and may reflect the effect of individual microbiomes. Future studies that simultaneously define the genomes and microbiomes of CCM patients will be required to test this intriguing hypothesis and determine whether the microbiome is a viable therapeutic target for this disease.

Methods

University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia) Mice

The Cdh5(PAC)-CreERT2 transgenic mice (iECre) were a generous gift from Ralf H. Adams39. Krit1fl/fl and Ccm2fl/fl animals have been previously described40,41. Tlr4fl/fl, Cd14−/−, Ai14 (R26-LSL-RFP), and R26-CreERT2 animals42–45 were obtained from the Jackson Laboratories. The Slco1c1(BAC)-CreERT2 transgenic mice (iBrECre) have been previously described18. All experimental animals were maintained on a mixed 129/SvJ, C57BL/6J, DBA/2J genetic background unless specifically described. C57BL/6J and timed pregnant Swiss Webster mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories. Germ-free Swiss Webster mice were purchased from Taconic. Breeding pairs between two and ten months of age were used to generate the neonatal CCM mouse model pups. Mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free facility where cages were changed on a weekly basis; ventilated cages, bedding, food, and acidified water (pH 2.5–3.0) were autoclaved prior to use, ambient temperature maintained at 23°C, and 5% Clidox-STM was utilized as a disinfectant. Experimental breeding cages were randomly housed on three different racks in the vivarium, and all cages were kept on automatic 12-hour light/dark cycles. The University of Pennsylvania Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) approved all animal protocols, and all procedures were performed in accordance with these protocols.

Centenary Institute (Australia) Mice

A portion of the resistant iECre;Ccm2fl/fl colony was exported to the Centenary Institute, Sydney, Australia where the mice were permanently maintained as an inbred colony in a quarantine facility. After several generations, this colony uniformly converted to lesion susceptibility. Cages were changed on a weekly basis; ventilated cages, bedding, food, and acidified water (pH 2.5–3.0) were autoclaved prior to use. Ambient temperature was maintained between 22–26°C, and 80% ethanol and F10SCTM (1:125 dilution of the concentrate, a quaternary ammonium compound) were used as disinfectants. Experimental breeding cages were randomly distributed throughout the vivarium, and all cages were kept on 12-hour light/dark cycles. The Sydney Local Health District Animal Welfare Committee approved all animal ethics and protocols. All experiments were conducted under the guidelines/regulations of Centenary Institute and the University of Sydney.

Gnotobiotic animal husbandry

Germ free Swiss Webster mice were purchased from Taconic and directly transferred into sterile isolators (Class Biologically Clean Ltd.) under the care of the Penn Gnotobiotic Mouse Facility. Food, bedding, and water (non-acidified) were autoclaved prior to transfer into the sterile isolators. Ventilated cages were changed weekly, and all cages in the vivarium were kept under 12-hour light/dark cycles. Microbiology testing (aerobic and anaerobic culture, 16S qPCR) was performed every ten days and fecal samples were sent to Charles Rivers Laboratories for pathology testing on a quarterly basis. Further details regarding the sterile C-section fostering can be found below. The University of Pennsylvania Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) approved all animal protocols, and all procedures were performed in accordance with these protocols.

Induction of the neonatal CCM mouse model

For all neonatal CCM mouse model experiments, at one-day post-birth (P1), pups were intragastrically injected by 30-gauge needle with 40 μg of 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4OHT, Sigma Aldrich, H7904) dissolved in a 9% ethanol/corn oil (volume/volume) vehicle (50 μL total volume per injection). This solution was freshly prepared from pre-measured, 4OHT powder for every injection. Prior to injection, the pup skin was sanitized using ethanol wipes. The P1 time point was defined by checking experimental breeding pairs every evening for new litters. The following morning (P1), pups were injected with 4OHT. All experimental pups were subjected to this induction regimen. For the Tlr4 rescue experiment (Fig. 2), and all lineage tracing experiments, an additional dose of 40 μg 4OHT was intragastrically delivered at P2 (P1+2, two total doses). Pups were then harvested as previously described9 at the specified time points.

Histology

Tissue samples were fixed in 4% formaldehyde overnight, dehydrated in 100% ethanol, and embedded in paraffin. 5 μm thick sections were used for hematoxylin & eosin and immunohistochemistry staining. The following antibodies were used for immunostaining: rat anti-PECAM (1:20, Histo Bio Tech DIA-310), rabbit anti-pMLC2 (1:200, Cell Signaling 3674S), goat anti-KLF4 (1:100, R&D AF3158), and rabbit anti-RFP (1:50, Rockland 600-401-379). Littermate control and experimental animal sections were placed on the same slide and immunostained at the same time under identical conditions. Images were taken at the same time using the same exposure times and color channels, and were subsequently overlaid using ImageJ.

Gram staining

Intra-abdominal abscesses were dissected and triturated in 500 μL of SOC medium. Drops of the mixture were placed on a microscope slide, briefly exposed to heat, and gram staining was performed using a kit from Sigma Aldrich (77730) following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Whole-mount retinal endothelium staining

Eyes from euthanized P17 mice were removed and fixed overnight in cold 4% PFA/PBS solution. The following day, retinas were dissected, cut into petals, and stained with isolectin-B4 conjugated to Alexa488 fluorophore (Thermo Fisher I21411) as previously described46. The retinas were then whole-mounted on microscopy slides in a flat, four-petal shape for fluorescence imaging.

Bacteroides fragilis (B. frag) abscess model

B. frag was purchased directly from the ATCC (strain 25285) and grown in chopped meat glucose (CMG) broth (Anaerobe Systems AS-813) under anaerobic conditions at 37°C. Autoclaved, degassed cecal contents (ACC) were generated by harvesting cecal contents from the colons of euthanized adult mice between 2–8 months of age. Cecal contents were then autoclaved and pulverized in an equal volume of CMG broth. This slurry was filtered through a 70 μm nylon strainer and degassed overnight in the anaerobic chamber. One mL of CMG broth was inoculated with B. frag and grown overnight to an optical density between 0.8 and 1.0. An equal volume of ACC was mixed with the overnight bacterial culture. 100 μL of this B. frag/ACC mixture was injected intraperitoneally into five-day old pups with a 31-gauge needle. Control littermates were simultaneously injected intraperitoneally with 100 μL of ACC alone. Pups were harvested at P17. Spleen weight was measured immediately after dissection, and all tissue was subsequently processed as described above.

Intravenous lipopolysaccharide (LPS), peptidoglycan (PGN), polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (poly(I:C)), interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα) injections

Lipopolysaccharide from E. coli O127:B8 was purchased from Sigma (L3129) and administered to the low lesion penetrance, resistant iECre;Ccm2fl/fl neonatal CCM disease model. At P5, a 3 μg dose of LPS dissolved in sterile PBS was administered retro-orbitally (RO) in a total 30 μL volume by 31-gauge needle. At P10, a 5 μg dose of LPS was administered RO in a total 50 μL volume by 31-gauge needle. Control animals were identically injected with PBS alone. Pups were euthanized and brains dissected at specified time points. PGN from Bacillus subtilis (a gram-positive gut commensal) was purchased from Invivogen (tlrl-pgnb3) and administered to the resistant iECre;Ccm2fl/fl neonatal CCM disease model under identical conditions as the LPS experiments. Poly(I:C) was purchased from Invivogen (tlrl-picw) and administered to the resistant iECre;Ccm2fl/fl neonatal CCM disease model under identical conditions as the LPS experiments.

Mouse IL-1β was purchased from Genscript (Z02988) and administered to the resistant iECre;Ccm2fl/fl neonatal CCM disease model. At P5, a 5 ng dose of IL-1β dissolved in sterile PBS was administered RO in a total 30 μL volume by 31-gauge needle. At P10, an 8 ng dose of IL-1β was administered RO in a total 50 μL volume by 31-gauge needle. Control animals were identically injected with PBS alone. Pups were euthanized and brains dissected at specified time points. Mouse TNFα was purchased from Genscript (Z02918) and administered to the resistant iECre;Ccm2fl/fl neonatal CCM disease model under identical conditions as the IL-1β experiments.

Contrast-enhanced, X-ray micro-computed tomography (microCT)

For all experiments utilizing microCT quantification of CCM lesion volume, brains were harvested and immediately placed in 4% PFA/PBS fixative. Brains remained in fixative until staining with non-destructive, iodine contrast and subsequent microCT imaging performed as previously described47. Importantly, all tissue processing, imaging, and volume quantification were done in a blinded manner by investigators at The University of Chicago without any knowledge of experimental details.

As previously done, we blinded samples at three distinct points in the analysis. First, neonatal CCM model pups were injected with 4OHT without knowledge of genotypes. Second, hindbrains from genotyped animals were given randomized, de-identified labels to provide for blinded microCT scanning by an independent operator. Third, randomized microCT image stacks were analyzed in a blinded manner by individuals not involved in any prior experimental steps.

Immune cell isolation from neonatal brain

Mice were anesthetized with AvertinTM and underwent intra-cardic perfusion with 10 mL of cold PBS. The brain was separated from the brainstem, and the cerebellum was separated from the remaining brain and processed in parallel. The tissue was minced with scissors, placed in digestion buffer (RPMI, 20mM HEPES, 10% FCS, 1mM CaCl2, 1mM MgCl2, 0.05mg/ml Liberase TM (Sigma), 0.02mg/ml DNase I (Sigma)), and incubated for 40 min at 37 °C with shaking at 200 rpm. The mixture was passed through a 100 μm strainer and washed with FACS Buffer (PBS, 1% FBS). Cells were resuspended in 4 mL of 40% Percoll (GE Healthcare) and overlaid on 4 mL of 67% Percoll. Gradients were centrifuged at 400 xg for 20 min at 4 °C and cells at the interface were collected, washed with 10 mL of FACS Buffer, and stained for flow cytometric analysis.

Hematopoietic cell isolation from neonatal whole blood, spleen and subsequent FACs analysis

Neonatal P10 mice were anesthetized with AvertinTM and underwent intracardiac puncture/blood draw using a 27 gauge needle/syringe coated with 0.5 M EDTA, pH 8.0 immediately prior to use. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 300 xg for 5 minutes at 4°C. Serum was removed and RBCs were lysed using ACK lysis buffer. Spleens were dissected in parallel, hand-homogenized using a mini-pestle and RBCs were lysed using ACK lysis buffer. Cells from both sets of tissues were passed through a 70 μm cell-strainer, pelleted, and resuspended in FACS buffer (PBS, 2% FBS, 0.1% NaN3) for immunostaining and subsequent FACS analysis.

Immune cell staining and flow cytometry analysis

Cells were isolated from the indicated tissues. Single-cell suspensions were stained with CD16/32 and with indicated fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies. Live/Dead Fixable Violet Cell Stain Kit (Invitrogen) was used to exclude non-viable cells. Multi-laser, flow cytometry analysis procedures were done at the University of Pennsylvania Flow Cytometry and Cell Sorting Facility using BD LSRII cell analyzers running FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences). Two-laser, flow cytometry analyses were done at the University of Pennsylvania iPS Cell Core using BD Accuri C6 instruments. FlowJo software (v.10 TreeStar) was used for data analysis and graphics rendering. All fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies used are listed as follows (Clone, Company, Catalog Number): CD11b (M1/70, Biolegend, 101255); CD11c (N418, Biolegend, 117318); CD16/32 (93, Biolegend, 101319); CD16/32 (93, eBiosciences, 56D0161D80); CD19 (6D5, Biolegend, 115510); CD3ε (145D2C11, Biolegend, 100304); CD4 (GK1.5, Biolegend, 100406); CD45 (30-F11, Biolegend, 103121 or 103151), CD8a (53D6.7, Biolegend, 100725); Foxp3 (FJK-16s, eBiosciences, 50-5773-82); Ly-6G (1A8, Biolegend, 127624); Live/Dead (N/A, Thermofisher, LD34966); NK1.1 (PK136, Biolegend, 108745); RORγt (B2D, eBiosciences, 12-6981-82); Siglec-F (E50D2440, BD, 562757); TCRγδ (UC7-13D5, Biolegend, 107504)

Isolation of cerebellar endothelial cells, lung endothelial cells, and gene expression analysis

At the specified time points, cerebellar endothelial cells were isolated through enzymatic digestion followed by separation using magnetic-activated cell sorting by anti-CD31 conjugated magnetic beads (MACS MS system, Miltenyl Biotec), as previously described9. Lung endothelial cells were isolated through enzymatic digestion as previously described followed by separation using anti-CD31 conjugated magnetic beads and the MACS MS system48. Isolated endothelial cells were pelleted and total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Micro kit (Qiagen 74004). For qPCR analysis, cDNA was synthesized from 300 ng to 500 ng total RNA using the SuperScriptTM VILO cDNA Synthesis Kit and Master Mix (Thermo Fisher 11755050). Real-time PCR was performed with Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher 4368577) using the primers listed:

mGapdh Forward: 5′- AAATGGTGAAGGTCGGTGTGAACG -3′

mGapdh Reverse: 5′- ATCTCCACTTTGCCACTGC -3′

mKlf2 Forward: 5′- CGCCTCGGGTTCATTTC -3′

mKlf2 Reverse: 5′- AGCCTATCTTGCCGTCCTTT -3′

mKlf4 Forward: 5′- GTGCCCCGACTAACCGTTG -3′

mKlf4 Reverse: 5′- GTCGTTGAACTCCTCGGTCT -3′

mKrit1 Forward: 5′- CCGACCTTCTCCCCTTGAAC -3′

mKrit1 Reverse: 5′- TCTTCCACAACGCTGCTCAT -3′

mIl1b Forward: 5′- GCAACTGTTCCTGAACTCAACT -3′

mIl1b Reverse: 5′- ATCTTTTGGGGTCCGTCAACT -3′

mSele Forward: 5′- ATGCCTCGCGCTTTCTCTC -3′

mSele Reverse: 5′- GTAGTCCCGCTGACAGTATGC -3′

mTlr4 Forward: 5′- ACTGGGGACAATTCACTAGAGC -3′

mTlr4 Reverse: 5′- GAGGCCAATTTTGTCTCCACA -3′

Identification of human CCM associated single nucleotide polymorphisms

As part of the Brain Vascular Malformation Consortium (BVMC) CCM study (Project 1), a large cohort of familial CCM individuals with identical KRIT1 Q455X mutations were enrolled between 2009 – 2014 at the University of New Mexico. All study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of New Mexico and University of California San Francisco (UCSF) and all procedures were done in accordance with these protocols. Prior to participation in the study, written informed consent was obtained from every patient and properly documented by UNM investigators.

At study enrollment, participants received a neurological examination (LM) and 3T MRI imaging using a volume T1 acquisition (MPRAGE, 1-mm slice reconstruction) and axial TSE T2, T2 gradient recall, susceptibility-weighted, and FLAIR sequences. Lesion counting by the neuroradiologist (BH) was based on concurrent evaluation of axial susceptibility-weighted imaging with 1.5-mm reconstructed images and axial T2 gradient echo 3-mm images.

Participants also provided blood or saliva samples for genetic studies. Genomic DNA was extracted using standard protocols. De-identified samples were normalized, plated on 96-well plates, and genotyped at the UCSF Genomics Core Facility using the Affymetrix Axiom Genome-wide LAT1 Human Array. Affymetrix Genotyping Console (GTC) 4.1 Software package was used to generate quality control metrics and genotype calls. All samples had genotyping call rates of ≥97% and were further checked for sample mix-ups (sex check, Mendelian errors and cryptic relatedness), resulting in 188 samples for genetic analysis.

21 candidate genes were further examined in the TLR4 and MEKK3-KLF2/4 signaling pathways (TLR4, CD14, MD-2, LBP, MYD88, TICAM1, TIRAP, TRAF1-6, MAP3K3, MEK5, ERK5, MEF2C, KLF2, KLF4, ADAMTS4, ADAMTS5) including 467 SNPs within 20kb upstream or downstream of each gene locus using UCSC Genome Browser coordinates (GRCh37/hg19). Because total lesion counts are highly right skewed, raw counts were log-transformed and analysis was performed on residuals (adjusted for age at enrollment and sex). To identify genotypes associated with log-transformed residual counts, linear regression analysis was implemented using QFAM family-based association tests for quantitative traits (PLINK v1.07 software), with stringent multiple testing correction (Bonferroni correction for the number of SNPs tested within each gene) given that some SNPs on the Affymetrix array were in linkage disequilibrium with each other, i.e., statistically correlated with r2>0.8.

Characterization of human cis-eQTLs

The Fehrmann dataset used for eQTL lookups consisted of peripheral blood samples from the United Kingdom and Netherlands49,50. Samples were genotyped with Illumina HumanHap300, HumanHap370 or 610 Quad platforms. Genotypes were input by Impute v251 using the GIANT 1000G p1v3 integrated call set for all ancestries as a reference52. Gene expression levels were measured by Illumina HT12v3 arrays. Gene expression pre-processing involved quantile normalization, log2 transformation, probe centering and scaling, population stratification correction (first 4 genetic multidimensional scaling components were removed from gene expression data) and correction for unknown confounders (first 20 gene expression principal components not associated with genetic variants were removed from gene expression data). Identification of potential sample mix-ups was conducted by MixupMapper21 and finally 1,227 samples remained. All pre-processing steps were performed with the QTL mapping pipeline v1.2.4D (https://molgenis26.target.rug.nl/downloads/eqtl-mapping-pipeline-1.2.4D-SNAPSHOT-dist.tar.gz).

These results are corroborated by an independently conducted GTEX Consortium study (http://www.gtexportal.org/home/snp/rs10759930 and http://www.gtexportal.org/home/snp/rs778587).

Tak242 and LPS-RS administration

Tak242 was purchased from EMD Millipore (614316) and administered to the neonatal CCM disease model. Five, seven, and nine days after birth, a 60 μg dose of Tak242 was dissolved in DMSO/sterile intralipid (Sigma, I141) vehicle and administered RO in a total volume of 30 μL. Control animals were identically injected with sterile DMSO/intralipid vehicle alone. Pups were euthanized and brains dissected 10 days after birth.

LPS-RS ultrapure was purchased from Invivogen (tlrl-prslps) and administered to the neonatal CCM disease model. Starting at P5, a 20 μg dose dissolved in sterile PBS was administered RO in a total volume of 30 μL every 24 hours. Control animals were identically injected with sterile PBS alone. Pups were euthanized and brains dissected 10 days after birth.

Transgenerational antibiotic administration

Experimental breeding pairs of mice, yielding susceptible neonatal CCM pups, were identified by induction of a neonatal CCM litter and evaluation of lesion burden. These breeding pairs then underwent timed matings and at E14.5, both male and female adult mice were subject to antibiotic-laced drinking water mixed with 40 g/L of sucralose and red food coloring. Antibiotic water was replaced daily. The following antibiotics were mixed with 0.22 μm-filtered water: penicillin (500 mg/L), neomycin (500 mg/L), streptomycin (500 mg/L), metronidazole (1 g/L), and vancomycin (1g/L). Antibiotics were purchased from the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania pharmacy. The neonatal CCM model was induced as described above. At P10, pups were euthanized and antibiotic water switched for normal drinking water. Experimental breeding pairs were then mated to obtain third generation, post-antibiotic pups.

Vancomycin mono-antibiotic administration

Co-housed, susceptible Krit1fl/fl females underwent evening-morning timed matings with a single susceptible iECre;Krit1fl/fl male. Upon detection of a plug in the morning, the females were subsequently separated into singly-housed cages. At E14.5, female mice were subject to either vancomycin (1 g/L)-laced or untreated (vehicle) sterile-filtered drinking water, changed daily. The drinking water was further mixed with 40 g/L sucralose and red food coloring. Pups were harvested at P11.

Bacterial DNA extraction from neonatal mouse guts and bacterial rDNA qPCR

The entire neonatal gut was dissected, snap-frozen on dry ice, and stored at −80°C. The QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen 51504 or 51604) was used to extract bacterial DNA from the neonatal gut. Prior to commencing the standard Qiagen protocol, the frozen gut was mixed in the included stool lysis buffer and homogenized with a 5 mm stainless steel bead in a TissueLyser LT (Qiagen 69980) at 50 hz for 10 minutes at 4°C. Concentration of the extracted DNA was equalized and 16 ng of DNA was used per qPCR reaction with universal bacterial 16S rRNA gene primers53, two different sets of previously characterized Bacteroidetes s24-7 primers54,55, and Firmicutes primers56.

Universal 16S rRNA Forward: 5′- ACTGAGAYACGGYCCA -3′

Universal 16S rRNA Reverse: 5′- TTACCGCGGCTGCTGGC -3′

Bacteroidetes s24-7 rRNA set 1 Forward: 5′- GGAGAGTACCCGGAGAAAAAGC -3′

Bacteroidetes s24-7 rRNA set 1 Reverse: 5′- TTCCGCATACTTCTCGCCCA -3′

Bacteroidetes s24-7 rRNA set 2 Forward: 5′- CCAGCAGCCGCGGTAATA -3′

Bacteroidetes s24-7 rRNA set 2 Reverse: 5′- CGCATTCCGCATACTTCTC -3′

Firmicutes rRNA Forward: 5′- TGAAACTYAAAGGAATTGACG -3′

Firmicutes rRNA Reverse: 5′- ACCATGCACCACCTGTC -3′

Sterile C-section and fostering to conventional Swiss Webster recipient females

Evening-morning timed matings to generate donor susceptible or resistant females yielding iECre;Krit1fl/fl or iECre;Ccm2fl/fl pups were performed and timed pregnant Swiss Webster females (Charles River 024) were ordered to serve as foster mothers. To prevent delivery of the pups, at E16.5, donor females were injected subcutaneously with 100 μL of a 15 μg/mL solution of medroxyprogesterone (Sigma Aldrich, M1629) dissolved in DMSO. The morning of E19.5, the donor mother was euthanized by cervical dislocation and submerged in a warm sterile solution of 1% VirkonSTM/PBS (weight/volume) for one minute. The uterus was then dissected in a sterile laminar flow hood, submerged in a warm sterile solution of 1% VirkonSTM/PBS for one minute and quickly rinsed with warm sterile PBS. Pups were then removed from the uterus and fostered to the Swiss Webster recipient female. The following morning, induction of the neonatal CCM model was performed as described above.

Sterile C-section and fostering to germ-free Swiss Webster recipient females

Timed matings were performed using germ-free Swiss Webster mice housed in sterile isolators under care of the University of Pennsylvania Gnotobiotic Mouse Facility. Simultaneous evening-morning timed matings were also performed using co-housed, susceptible Krit1fl/fl females and iECre;Krit1fl/fl males previously characterized to yield CCM-susceptible pups. Medroxyprogesterone was administered to donor females and the sterile C-section was performed at E19.5 as described in the previous section. The intact uterus was passed through a J-tube filled with warm 1% VirkonSTM/PBS that was hermetically sealed to the sterile isolator. Pups were dissected from the uterus inside the sterile isolator and fostered to the recipient germ-free Swiss Webster mother. Approximately one week later, fecal samples were collected for microbiology testing. Germ-free status was further confirmed by 16S qPCR of bacterial DNA isolated from maternal feces and neonatal guts.

Collection of maternal CCM mouse feces

Fresh fecal pellets were collected from experimental females yielding susceptible or resistant pups one day after harvesting the pups to determine phenotypic severity. Collection was performed between four and six PM, pellets were immediately snap-frozen on dry ice, and stored at −80°C.

Extraction and library preparation of bacterial DNA for 16S rRNA gene sequencing

DNA was extracted from stool samples using the Power Soil htp kit (Mo Bio Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Library preparation was performed by utilizing previously described barcoded primers targeting the V1 V2 region of the 16S rRNA gene57. PCR reactions were performed in quadruplicate using AccuPrime Taq DNA Polymerase High Fidelity (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Each PCR reaction consisted of 0.4 μM primers, 1x AccuPrime Buffer II, 1 U Taq, and 25 ng DNA. PCRs were run using the following parameters: 95°C for 5 min; 20 cycles of 95°C for 30 sec, 56°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 90 sec; and 72°C for 8 min. Quadruplicate PCR reactions were pooled and products were purified using AMPureXP beads (Beckman-Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). Equimolar amounts from each sample were pooled to produce the final library. Positive and negative controls were carried through the amplification, purification, and pooling procedures. Negative controls were used to assess reagent contamination and consisted of extraction blanks and DNA-free water. Positive controls were used to assess amplification and sequencing quality and consisted of gBlock DNA (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, Iowa, USA) containing non- bacterial 16S rRNA gene sequences flanked by bacterial V1 and V2 primer binding sites. Paired-end 2x250bp sequence reads were obtained from the MiSeq (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) using the 500 cycle v2 kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA).

Analysis of 16S sequencing

Sequence data were processed using QIIME version 1.9.158. Read pairs were joined to form a complete V1V2 amplicon sequence. Resulting sequences were quality filtered and demultiplexed. Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) were selected by clustering reads at 97% sequence similarity59. Taxonomy was assigned to each OTU with a 90% sequence similarity threshold using the Greengenes reference database60. A phylogenetic tree was inferred from the OTU data using FastTree61. The phylogenetic tree was then used to calculate weighted and unweighted UniFrac distances between each pair of samples in the study62,63. Microbiome compositional differences were visualized using Principle Coordinates Analysis (PCoA). Community-level differences between mice genetic background as well as disease susceptibility groups were assessed using a PERMANOVA test64 of weighted and unweighted UniFrac distances. To assess significance in the PERMANOVA test, each cage was randomly re-assigned to groups 9999 times. Differential abundance was assessed for taxa present in at least 80% of the samples, using generalized linear mixed effects models. For tests of taxon abundance, the cage was modeled as a random effect, as previous research has established that the fecal microbiota of mice are correlated within cages65. The p-values were corrected for multiple testing using Benjamini-Hochberg method.

Statistics

Sample sizes were estimated based on our previous experience with the neonatal CCM model and lesion volume quantitation by microCT9. Using forty historically collected, susceptible iECre;Krit1fl/fl and iECre;Ccm2fl/fl P10 brains, we calculated a sample standard deviation of 0.250 mm3. Between iECre;Krit1fl/fl and iECre;Ccm2fl/fl genotypes, an F-test to compare variances confirmed no significant difference (p=0.340). Thus, for a two-group comparison of lesion volumes, each sample group requires seven animals for a desired statistical power of 95% (β= 0.05), and a conventional significance threshold of 5% (α= 0.05) assuming an effect size of 50% (0.5) and equal standard deviations between sample groups. These predictive calculations were corroborated by our recent publication in which larger effect sizes (>90%) were found to be statistically significant with four to five samples per group9. All experimental and control animals were littermates and none were excluded from analysis at the time of harvest. Experimental animals were lost or excluded at two pre-defined points: (i) failure to properly inject 4OHT and observation of significant leakage; (ii) death prior to P10 because of injection or chaos. Given the early time points, no attempt was made to distinguish or segregate results based on neonatal genders. P-values were calculated as indicated in figure legends using an unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test; one-way ANOVA with multiple comparison corrections (Holm-Sidak or Bonferroni); PERMANOVA; or linear mixed effects modeling. As indicated in the figure legends, the standard error of the mean (s.e.m.), 95% confidence interval, or boxplot is shown.

Data availability

All relevant data are available from the authors upon request.

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1. CCM formation in resistant iECre;Ccm2fl/fl animals is stimulated by abscess formation and LPS.

a, Resistance to CCM formation is maintained in a C57BL/6J strain background. iECre;Ccm2fl/fl animals were back-crossed 7 generations onto a C57BL/6J background and gene deletion induced at P1 with visual hindbrain assessment at P10. N=7. Scale bars, 1 mm. b, Retinal CCM formation is stimulated by gram negative bacterial infection. Retinas of P17 resistant iECre;Ccm2fl/fl littermates are shown. The sample shown below is from the animal that developed the spontaneous gram negative abscess shown in Fig. 1c. Scale bars, 500 μm. c–d, Administration of LPS does not drive CCM formation in Cre-negative neonatal mice. LPS was administered intravenously to Ccm2fl/fl and iECre;Ccm2fl/fl littermates as shown in Figure 1g, and hindbrains assessed at P17 visually (c) and histologically (H&E staining, d). N≥3 per group. Scale bars, 1 mm (c) and 100 μm (d). e, LPS induces myosin light chain activation in CCM-deficient brain endothelial cells. Phospho-myosin light chain (pMLC) and PECAM staining of hindbrains from P5 LPS- or vehicle-injected resistant iECre;Ccm2fl/fl littermates. Dotted lines trace the purkinje cell layer. N≥4 per group. Scale bars, 50 μm. f, Tlr4 expression does not differ between CCM susceptible and resistant animals. Tlr4 expression was measured using qPCR in cerebellar endothelial cells isolated from the indicated animals at P10. Error bars shown as s.e.m. and significance determined by unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test. n.s. indicates p>0.05.

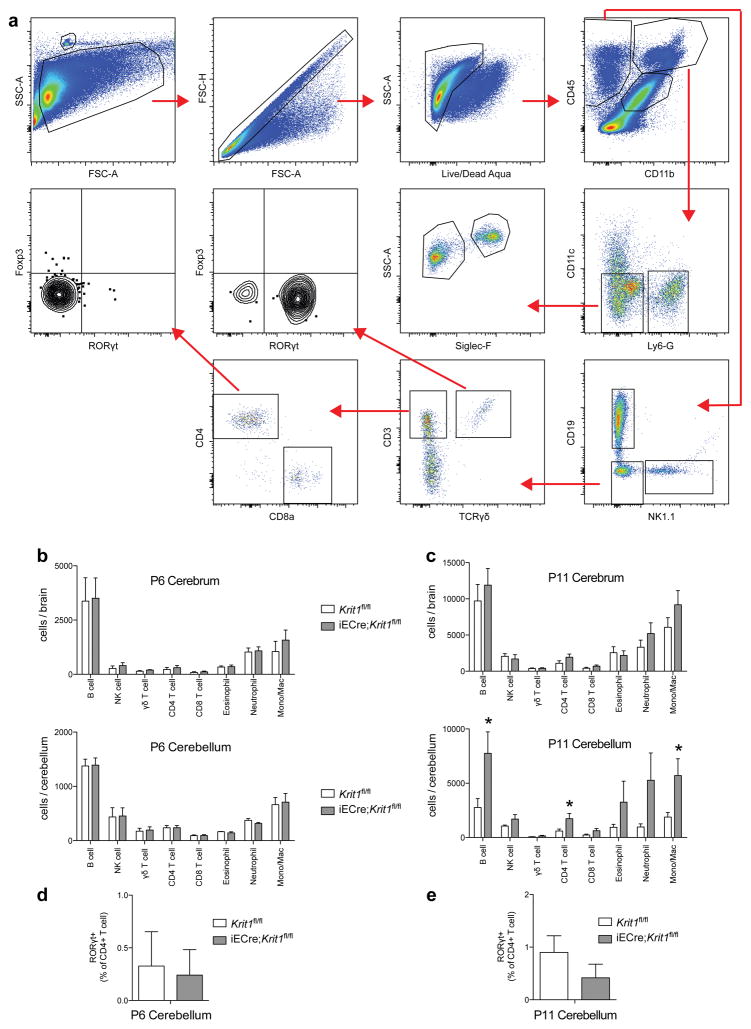

Extended Data Figure 2. Analysis of immune cells in P6 and P11 Krit1fl/fl and iECre;Krit1fl/fl brains.

a, Gating strategy for B cells, NK cells, γδ T cells, CD4 T cells, CD8 T cells, eosinophils, neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages from cerebrum and cerebellum is shown. Cellular surface markers used were as follows: Neutrophils (CD45+, CD11b+, Ly6-G+), Eosinophils (CD45+, CD11b+, CD11c−, Ly6G−, Siglec-F+, SSChi), Monocyte/Macrophage (CD45+, CD11b+, CD11c−, Ly6G−, Siglec-F−, SSClo), NK cells (CD45+, CD11b−, CD19−, NK1.1+), B cells (CD45+, CD11b−, NK1.1−, CD19+), γδ T cell (CD45+, CD11b−, NK1.1−, CD19−, CD3+, TCRγδ+), CD4 T cell (CD45+, CD11b−, NK1.1−, CD19−, CD3+, TCRγδ−, CD8−, CD4+), CD8 T cell (CD45+, CD11b−, NK1.1−, CD19−, CD3+, TCRγδ−, CD4−, CD8+). b, The number of B cells, NK cells, γδ T cells, CD4 T cells, CD8 T cells, eosinophils, neutrophils, and monocytes/macrophages isolated from P6 cerebrum (top) and cerebellum (bottom) is shown for susceptible Krit1fl/fl and iECre;Krit1fl/fl littermates. N≥6 per group. No significant differences were detected. c, The number of B cells, NK cells, γδ T cells, CD4 T cells, CD8 T cells, eosinophils, neutrophils, and monocytes/macrophages isolated from P11 cerebrum (top) and cerebellum (bottom) is shown for susceptible Krit1fl/fl and iECre;Krit1fl/fl littermates. N≥6 per group. d–e, Frequency of RORγt+ CD4 T cells isolated from P6 and P11 cerebellum. N≥6 per group. Error bars of all graphs shown as s.e.m. and significance determined by unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test. *indicates p<0.05. Note that there is significant immune cell presence in the cerebellum of susceptible iECre;Krit1fl/fl animals at P11 but not at P6.

Extended Data Figure 3. Changes in the volume of CCM lesions are not accompanied by changes in total brain volume.

The indicated total brain volumes were measured using microCT imaging. a–b, Brain volumes corresponding to the genetic rescue experiments shown in Fig. 2c–f, respectively. c, Brain volumes corresponding to the C-section/germ free fostering experiment shown in Fig. 4b–c. d, Brain volumes corresponding to the intergenerational antibiotic experiment shown in Fig. 6f–h and j. n.s. indicates p>0.05.

Extended Data Figure 4. Lineage tracing of the Cdh5(PAC)-CreERT2 (iECre) transgene in neonatal mice.

a–c, R26-LSL-RFP, R26-CreERT2;R26-LSL-RFP, and Cdh5(PAC)-CreERT2;R26-LSL-RFP neonates were induced with doses of tamoxifen on P1+2 (two total doses) and CD45+;RFP+ hematopoietic cell numbers in the spleen and peripheral blood assessed at P10. N≥5 per group. Error bars shown as s.e.m. and significance determined by one-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak correction for multiple comparisons. ***indicates p<0.001; n.s. indicates p>0.05. Note that the number of labeled hematopoietic cells in Cdh5(PAC)-CreERT2;R26-LSL-RFP animals is indistinguishable from R26-LSL-RFP negative control animals, while >90% of CD45+ cells were RFP+ in R26-CreERT2;R26-LSL-RFP positive control animals. d, Anti-RFP and anti-PECAM immunostaining of P10 hindbrains from Krit1fl/fl;R26-LSL-RFP negative control and iECre;Krit1fl/fl;R26-LSL-RFP was performed to identify Cre+ descendants at the site of CCM formation. Note that all RFP+ cells in iECre;Krit1fl/fl;R26-LSL-RFP animals are PECAM+, consistent with endothelial-specific Cre activity. Asterisk indicates CCM lesion. Results are representative of ≥ 3 per group. Scale bars, 100 μm.

Extended Data Figure 5. The Slco1c1(BAC)-CreERT2 (iBrECre) transgene expresses selectively in brain endothelial cells and iBrECre-driven deletion of Krit1 confers CCM formation in neonatal mice.

a, R26-LSL-RFP, Cdh5(PAC)-CreERT2;R26-LSL-RFP and Slco1c1(BAC)-CreERT2;R26-LSL-RFP neonates were induced with tamoxifen injection on P1+2 (two total doses). Immunostaining for RFP and PECAM was performed at P10 in the indicated tissues. Results are representative of at least three animals per group and three independent experiments. Scale bars, 100 μm. Note the presence of RFP+ PECAM+ cells in the brain, small intestine, cecum, colon and liver of Cdh5(PAC)-CreERT2;R26-LSL-RFP animals, but only in the brain of Slco1c1(BAC)-CreERT2;R26-LSL-RFP animals. b, Visual (top) and corresponding microCT (bottom) images of brains from susceptible iBrECre;Krit1fl/+ and iBrECre;Krit1fl/fl P10 animals. Arrow indicates CCM lesions in the cerebrum. Scale bars, 1 mm. c, H&E staining of cerebellum (hindbrain) from the indicated animals (left). H&E staining of cerebrum (forebrain) from the indicated animals (middle). KLF4 and PECAM immunostaining from the indicated animals (right). Scale bars, 50 μm. Asterisks denote CCM lesions. N≥5 per group.

Extended Data Figure 6. CCM formation can be stimulated by IL-1β or poly(I:C) treatment.

a, Schematic of the experimental design in which littermates receive a retro-orbital injection of the indicated cytokine or TLR ligand at P5 and P10 prior to tissue harvest and analysis at P17. b–m, Visual images and volumetric quantitation of CCM lesions in the hindbrains of P17 iECre;Ccm2fl/fl littermates injected with the indicated cytokines, TLR ligands, or vehicle control are shown. Error bars shown as s.e.m. and significance determined by unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test. *indicates p<0.05; n.s. indicates p>0.05. Scale bars, 1 mm.

Extended Data Figure 7. 16s rRNA sequencing results from susceptible and resistant Krit1fl/fl and Ccm2fl/fl dams.

a, Heat map showing relative abundance of bacterial taxa (right) identified in susceptible (blue) and resistant (salmon) Krit1 (ccm1, purple) and Ccm2 (ccm2, green) animals (top). b, Box plots of bacterial taxa that demonstrated significant differential abundance in susceptible versus resistant animals and the relative abundance of those taxa. c, Boxplot of the Firmicutes [Ruminococcus] taxon that displayed significant differential abundance between Krit1 and Ccm2 genotypes. Note that the relative abundance of Bacteroidetes s24-7 is anywhere from 10 to 10,000-fold greater than any other taxon. Significance (p<0.05) for b and c determined by linear mixed effects modeling with Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiple comparisons.

Extended Data Figure 8. Blockade of CCM formation by the TLR4 antagonist LPS-RS.

a, Schematic of the experimental design in which iECre;Krit1fl/fl littermates receive retro-orbital injections of the TLR4 antagonist LPS-RS. b, Visual (left) and microCT (right) images of hindbrains from vehicle or LPS-RS injected animals. c–d, Quantitation of CCM lesion and brain volume in iECre;Krit1fl/fl littermates treated with vehicle or LPS-RS. Error bars shown as s.e.m. and significance determined by unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test. **indicates p<0.01; n.s. indicates p>0.05. All scale bars, 1 mm.

Extended Data Figure 9. CCM formation is stimulated by spontaneous abscess formation and not blocked by vancomycin.

a, P10 hindbrains from Generation 3/Post ABX iECre;Krit1fl/fl littermates in the longitudinal antibiotic experiment described in Fig 6e–l. The animal with a large CCM lesion burden on the far right was found to have an abdominal abscess (circle, “absc”) and splenomegaly (arrow, lower right). Scale bar, 1 mm. b, Schematic of the experimental design in which cohoused, lesion susceptible iECre;Krit1fl/fl mating pairs were used to test the acute effect of vancomycin treatment on CCM formation. Offspring were studied after receiving maternal vehicle or vancomycin administered from E14.5 to P11. c–d, Visual images of hindbrains from representative offspring following vehicle or vancomycin antibiotic treatment. Scale bars, 1 mm. e–f, Volumetric quantitation of CCM lesions and brain volumes in iECre;Krit1fl/fl littermates treated with vehicle or vancomycin. g–h, Relative quantitation of total neonatal gut bacterial load measured by qPCR of bacterial universal 16S or Firmicutes-specific rRNA gene copies. N≥6 per group. Error bars of all graphs shown as s.e.m. and significance determined by unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test. n.s. indicates p>0.05. ****indicates p<0.0001; n.s. indicates p>0.05.

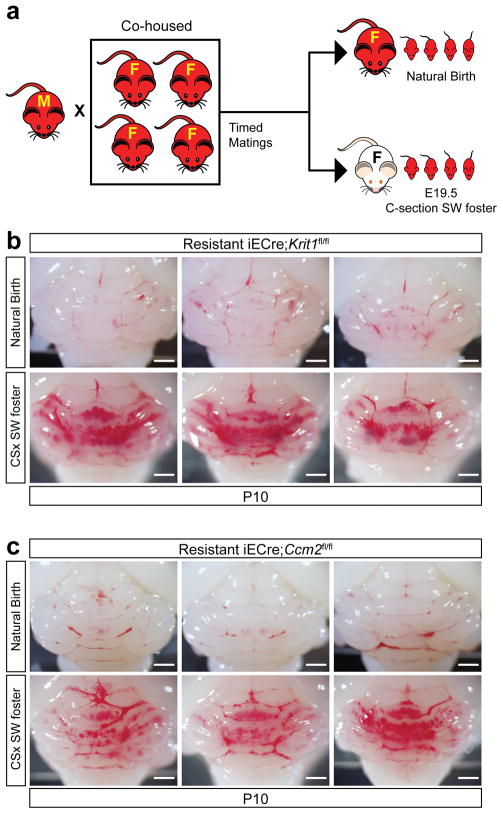

Extended Data Figure 10. CCM formation is conferred to the offspring of resistant animals by fostering to Swiss-Webster mothers.

a, Schematic of the experimental design in which timed matings of resistant iECre;Krit1fl/fl and resistant iECre;Ccm2fl/fl mating pairs were used to generate E19.5 offspring delivered by natural birth and raised by the birth mother or C-section/fostered to conventional Swiss-Webster foster mothers. b–c, Visual images of hindbrains from P10 resistant iECre;Krit1fl/fl and iECre;Ccm2fl/fl offspring following natural delivery and nursing by resistant mothers or after C-section/fostering to Swiss-Webster mothers. N≥6 per group.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lauren Goddard, other lab members, and Katherine Szigety for their comments during this work. We appreciate the guidance of our colleagues: Gary Wu, Rick Bushman, and Yongwon Choi. We acknowledge valuable technical assistance with B. fragilis culture from Owen Jensen and Jun Zhu; 16S sequencing and analysis by Dorothy Kim, Lisa Mattei, and Kyle Bittinger from the PennCHOP Microbiome Core; germ-free mouse husbandry from Katie Rickershauser and the Penn Gnotobiotic Mouse Facility; KRIT1 Q455X screening and Affymetrix genotyping of human samples from Diana Guo and Ludmila Pawlikowska; MRI images from Mary Bartlett; patient data analysis from Jeffrey Nelson; data sorting from Yu Tang; artwork from Lili Guo. We thank Amy Ackers and Angioma Alliance for patient enrollment. These studies were supported by National Institute of Health grants R01HL094326 (MK), P01NS092521 (MK and IA), R01NS075168 (KW), T32HL07439 (AT), F30NS100252 (AT), T32DK007780 (JK), DFG grant SCHWD-416/5-2 (MS), U54NS065705 (HK, LM, BH), a Penn-CHOP Microbiome Pilot & Feasibility Award Grant (MK), and Australian NHMRC project grant 161558 (XZ).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

AT designed and performed most of the experiments. JC and XZ performed parallel studies in Sydney. JK and JH performed immunophenotyping experiments. YY and CH performed lineage tracing experiments. PM and MC assisted in numerous experimental studies. JY and LL performed histologic analysis. RG, HZ, TM, RL, YC, NH, RS and IA performed all microCT lesion imaging and measurements in a blinded manner. CT performed bioinformatics analysis on 16S sequencing results. DK performed germ-free fostering experiments. UV and LF provided human eQTL data for TLR4 and CD14. KW, DL, and MS provided critical reagents. BH, LM and HK provided analysis of KRIT1 Q455X patients. AT, JC, JK, CH, CT, UV, HK, and MK designed experiments and wrote the manuscript.

Competing financial interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Fischer A, Zalvide J, Faurobert E, Albiges-Rizo C, Tournier-Lasserve E. Cerebral cavernous malformations: from CCM genes to endothelial cell homeostasis. Trends Mol Med. 2013;19:302–308. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fisher OS, Boggon TJ. Signaling pathways and the cerebral cavernous malformations proteins: lessons from structural biology. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS. 2014;71:1881–1892. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1532-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Plummer NW, Zawistowski JS, Marchuk DA. Genetics of cerebral cavernous malformations. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2005;5:391–396. doi: 10.1007/s11910-005-0063-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Denier C, et al. Clinical features of cerebral cavernous malformations patients with KRIT1 mutations. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:213–220. doi: 10.1002/ana.10804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Denier C, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlations in cerebral cavernous malformations patients. Ann Neurol. 2006;60:550–556. doi: 10.1002/ana.20947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choquet H, et al. Polymorphisms in inflammatory and immune response genes associated with cerebral cavernous malformation type 1 severity. Cerebrovascular diseases. 2014;38:433–440. doi: 10.1159/000369200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cullere X, Plovie E, Bennett PM, MacRae CA, Mayadas TN. The cerebral cavernous malformation proteins CCM2L and CCM2 prevent the activation of the MAP kinase MEKK3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1510495112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cuttano R, et al. KLF4 is a key determinant in the development and progression of cerebral cavernous malformations. EMBO Mol Med. 2015 doi: 10.15252/emmm.201505433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou Z, et al. Cerebral cavernous malformations arise from endothelial gain of MEKK3-KLF2/4 signalling. Nature. 2016;532:122–126. doi: 10.1038/nature17178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Renz M, et al. Regulation of beta1 integrin-Klf2-mediated angiogenesis by CCM proteins. Dev Cell. 2015;32:181–190. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher OS, et al. Structure and vascular function of MEKK3-cerebral cavernous malformations 2 complex. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7937. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang X, et al. Structural Insights into the Molecular Recognition between Cerebral Cavernous Malformation 2 and Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Kinase Kinase 3. Structure. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.str.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boulday G, et al. Developmental timing of CCM2 loss influences cerebral cavernous malformations in mice. J Exp Med. 2011 doi: 10.1084/jem.20110571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poltorak A, et al. Defective LPS signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr mice: mutations in Tlr4 gene. Science. 1998;282:2085–2088. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang Q, et al. Differential regulation of interleukin 1 receptor and Toll-like receptor signaling by MEKK3. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:98–103. doi: 10.1038/ni1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wright SD, Ramos RA, Tobias PS, Ulevitch RJ, Mathison JC. CD14, a receptor for complexes of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and LPS binding protein. Science. 1990;249:1431–1433. doi: 10.1126/science.1698311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zanoni I, et al. CD14 controls the LPS-induced endocytosis of Toll-like receptor 4. Cell. 2011;147:868–880. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ridder DA, et al. TAK1 in brain endothelial cells mediates fever and lethargy. J Exp Med. 2011;208:2615–2623. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jaekal J, et al. Individual LPS responsiveness depends on the variation of toll-like receptor (TLR) expression level. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;17:1862–1867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalis C, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 expression levels determine the degree of LPS-susceptibility in mice. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:798–805. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Westra HJ, et al. Systematic identification of trans eQTLs as putative drivers of known disease associations. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1238–1243. doi: 10.1038/ng.2756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Consortium GT. Human genomics. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) pilot analysis: multitissue gene regulation in humans. Science. 2015;348:648–660. doi: 10.1126/science.1262110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erridge C. Endogenous ligands of TLR2 and TLR4: agonists or assistants. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;87:989–999. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1209775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horng T, Barton GM, Flavell RA, Medzhitov R. The adaptor molecule TIRAP provides signalling specificity for Toll-like receptors. Nature. 2002;420:329–333. doi: 10.1038/nature01180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang J, et al. The essential role of MEKK3 in TNF-induced NF-kappaB activation. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:620–624. doi: 10.1038/89769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.West XZ, et al. Oxidative stress induces angiogenesis by activating TLR2 with novel endogenous ligands. Nature. 2010;467:972–976. doi: 10.1038/nature09421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dunne A, O’Neill LA. The interleukin-1 receptor/Toll-like receptor superfamily: signal transduction during inflammation and host defense. Sci STKE. 2003;2003:re3. doi: 10.1126/stke.2003.171.re3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elinav E, et al. NLRP6 inflammasome regulates colonic microbial ecology and risk for colitis. Cell. 2011;145:745–757. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zaki MH, et al. The NLRP3 inflammasome protects against loss of epithelial integrity and mortality during experimental colitis. Immunity. 2010;32:379–391. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wlodarska M, et al. NLRP6 inflammasome orchestrates the colonic host-microbial interface by regulating goblet cell mucus secretion. Cell. 2014;156:1045–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Birchenough GM, Nystrom EE, Johansson ME, Hansson GC. A sentinel goblet cell guards the colonic crypt by triggering Nlrp6-dependent Muc2 secretion. Science. 2016;352:1535–1542. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf7419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsunaga N, Tsuchimori N, Matsumoto T, Ii M. TAK-242 (resatorvid), a small-molecule inhibitor of Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 signaling, binds selectively to TLR4 and interferes with interactions between TLR4 and its adaptor molecules. Mol Pharmacol. 2011;79:34–41. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.068064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coats SR, Pham TT, Bainbridge BW, Reife RA, Darveau RP. MD-2 mediates the ability of tetra-acylated and penta-acylated lipopolysaccharides to antagonize Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide at the TLR4 signaling complex. J Immunol. 2005;175:4490–4498. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.7.4490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Banks WA. From blood-brain barrier to blood-brain interface: new opportunities for CNS drug delivery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15:275–292. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2015.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Banks WA, Robinson SM. Minimal penetration of lipopolysaccharide across the murine blood-brain barrier. Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24:102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rossignol DP, Lynn M. TLR4 antagonists for endotoxemia and beyond. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2005;6:496–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gilbert JA, et al. Microbiome-wide association studies link dynamic microbial consortia to disease. Nature. 2016;535:94–103. doi: 10.1038/nature18850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Palm NW, et al. Immunoglobulin A coating identifies colitogenic bacteria in inflammatory bowel disease. Cell. 2014;158:1000–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Y, et al. Ephrin-B2 controls VEGF-induced angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Nature. 2010;465:483–486. doi: 10.1038/nature09002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mleynek TM, et al. Lack of CCM1 Induces Hypersprouting and Impairs Response to Flow. Hum Mol Genet. 2014 doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zheng X, et al. Dynamic regulation of the cerebral cavernous malformation pathway controls vascular stability and growth. Dev Cell. 2012;23:342–355. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McAlees JW, et al. Distinct Tlr4-expressing cell compartments control neutrophilic and eosinophilic airway inflammation. Mucosal Immunol. 2015;8:863–873. doi: 10.1038/mi.2014.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moore KJ, et al. Divergent response to LPS and bacteria in CD14-deficient murine macrophages. J Immunol. 2000;165:4272–4280. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.8.4272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Madisen L, et al. A robust and high-throughput Cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nature neuroscience. 2010;13:133–140. doi: 10.1038/nn.2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ventura A, et al. Restoration of p53 function leads to tumour regression in vivo. Nature. 2007;445:661–665. doi: 10.1038/nature05541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tual-Chalot S, Allinson KR, Fruttiger M, Arthur HM. Whole mount immunofluorescent staining of the neonatal mouse retina to investigate angiogenesis in vivo. J Vis Exp. 2013:e50546. doi: 10.3791/50546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Girard R, et al. Micro-Computed Tomography in Murine Models of Cerebral Cavernous Malformations as a Paradigm for Brain Disease. J Neurosci Methods. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2016.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]