Abstract

Children's health and wellbeing is high on the research and policy agenda of many nations. There is a wealth of epidemiological research linking childhood circumstances and health practices with adult health. However, echoing a broader picture within child health research where children have typically been viewed as objects rather than subjects of enquiry, we know very little of how, in their everyday lives, children make sense of health-relevant information.

This paper reports key findings from a qualitative study exploring how children understand food in everyday life and their ideas about the relationship between food and health. 53 children aged 9-10, attending two socio-economically contrasting schools in Northern England, participated during 2010 and 2011. Data were generated in schools through interviews and debates in small friendship groups and in the home through individual interviews. Data were analysed thematically using cross-sectional, categorical indexing.

Moving beyond a focus on what children know the paper mobilises the concept of health literacy (Nutbeam, 2000), explored very little in relation to children, to conceptualise how children actively construct meaning from health information through their own embodied experiences. It draws on insights from the Social Studies of Childhood (James and Prout, 2015), which emphasise children's active participation in their everyday lives as well as New Literacy Studies (Pahl and Rowsell, 2012), which focus on literacy as a social practice. Recognising children as active health literacy practitioners has important implications for policy and practice geared towards improving child health.

Keywords: Children, Health literacy, Qualitative, UK

Highlights

-

•

Children access a range of often contradictory health information from diverse sources.

-

•

Children engage critically with health information through their own embodied experiences.

-

•

An understanding of children's health literacy practices should inform health education.

1. Introduction

1.1. The significance of child health

A wealth of epidemiological research links childhood circumstances, practices and health status with adult health outcomes and children are frequently positioned as ‘represent[ing] the future’ (World Health Organisation (WHO), 2015). It is not surprising, therefore, that improving child health and wellbeing is high on the research and policy agendas of many nations. There are over 2.2 billion children (aged 0-15 years) worldwide and in some countries children comprise nearly fifty percent of the population (UNICEF, 2014). While recognising the value of this life course perspective in underscoring the importance of child health, a number of commentators have highlighted the need to focus on children's present time health and wellbeing as an important end in itself (Blair et al., 2010, Parton, 2006). Indeed, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), adopted by all but two of the UN member states, outlines children's right to enjoy their childhood and their right to health (United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), 1989).

1.2. Health promotion and health education geared towards children

Alongside strategies which aim to influence the social determinants of health (for example, reducing child poverty and improving educational outcomes (United Nations (UN), 2015)), health education is viewed as an important element of child health promotion. The extent to which health education embodies children's right ‘to be heard and listened to’ (United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), 1989), however, is a contested issue. St Leger (2001), for example, argues that in the majority of schools in many countries, health education is characterised by a focus on conveying knowledge and developing competencies and acceptable attitudes (p. 1999). Such critiques echo Freire's (1993) conceptualisation of a ‘banking’ approach to health education: didactic teaching which characterises recipients as empty vessels waiting to be filled with knowledge and attitudes. Evans et al. (2011), go further, arguing that school-based teaching about healthy eating, a key contemporary focus in health promotion, positions children as mere ‘vectors to carry information on “healthy lifestyles” from educational spaces back to more responsible actors within the home (parents)’ (p. 324).

This framing of health promotion in relation to children's lives echoes broader, adult perspectives in child health policy and research where children have typically been viewed as objects of health promoting inputs (Christensen, 2004, Wills et al., 2008). This adult or adultist perspective has emphasised the role of adults in shaping child health to the exclusion of multiple other factors which may also have relevance to their lives. It underwrites a preeminent focus on objective measures of child health to the neglect of the underlying processes and complexities, which might explain these, including children's own contributions to their health (Christensen, 2004; Graham and Power, 2004; Wills et al., 2008). This view of children and its consequences for the research agenda in child health reflect what has been termed the ‘dominant framework’ for understanding children. With its roots in both sociology and developmental psychology, the dominant framework focuses on children's lack of competence. Children are portrayed as needing to be socialized to gain awareness of cultural values and conventions and as repositories for information 'deposited' by adults (Christensen, 2004).

1.3. Locating ‘the child’ in child health

In sharp contrast to this deficit approach, a Social Studies of Childhood (James and Prout, 2015) framework depicts children as competent social actors who have informed and informing views of the social world. Attention is focused on positive notions of competence recognising that age-based, adult-determined contexts can constrain children's agency and undermine their competencies. Researchers working within a Social Studies of Childhood framework have explored the sense that children make of their worlds and demonstrate that children are not merely passive recipients of socialisation but, rather, are active and reflective and can exhibit competencies that challenge a rigid ages and stages approach to understanding (Corsaro, 2003, Buckingham, 2000, Adler and Adler, 1998). Acknowledging Prout's (2005) criticism that a purely social constructionist perspective of childhood risks underplaying the materiality of life (access to resources, technology, and the physical body), the Social Studies of Childhood implies a commitment to exploring the variety of childhoods and children's lived experiences and motivates researchers to describe the diversity of children's lives within their social contexts (Matthews, 2007).

Alongside a wealth of research describing how children experience ill health and disability, over recent decades a small but growing body of research within the Social Studies of Childhood has begun to explore how, in their everyday lives, children are active in and reflective upon their own health. In Negotiating Health, for example, a qualitative study of primary school children's health behaviours, Mayall (1998) characterises children as ‘embodied healthcare actors’ (p.278) as she demonstrates how they carry out health-related activities at home and school. Christensen (2004) goes further; echoing Freire's assertion that through education people can be ‘subjects and actors in their own lives and in society’ (Wallerstein, 1988, p. 382). Christensen (2004) argues that children can be agents for health, ‘health promoting actors’ (p.328), within the family. Christensen suggests that children should be seen as actors in their own right and that research should ask how children become involved in and, indeed, proactive in health practices while growing up (Christensen, 2004, p. 379). She outlines some key ways in which children have the potential to be health-promoting actors including self-care, keeping fit and active, developing and maintaining relationships and developing knowledge, skills, competencies, values, goals and behaviours conducive to good health. Indeed, a recent anthology of work in this field demonstrates the importance of research 'with children and from a child's perspective, in order to fully understand the meaning and impact of health and illness in children's lives' (Brady et al., 2015, p. 1).

However, despite this fertile ground for research and despite the fact that more assets based approaches from the children's rights literature are beginning to inform health policy at an international level (UNICEF, 2014, Search Institute, 2016) very little work has taken a child-centred approach to explore how, in their everyday lives, children construct health-relevant understandings. In particular, the ways in which children interact with health information and how this does or does not become meaningful remains under-researched and under-theorised.

1.4. Understanding health: health literacy

One way of thinking about how people learn about and make sense of health-relevant information is through the concept of health literacy. Although sometimes confined, in the medical literature, to very narrow definitions relating to how people process and understand basic health information (Institute of Medicine (IoM), 2004), including their ability to comply with therapeutic regimens (AdHoc Committee on Health Literacy for the Council of Scientific Affairs AMA, 1999), the concept of health literacy can encapsulate much broader ideas about how individuals interact with health messages. Recognising that it remains a highly contested concept (Bankson, 2009), Nutbeam's (2000) definition has been very influential: 'The personal, cognitive and social skills which determine the ability of individuals to gain access to, understand, and use information to promote and maintain good health' (p.263). Nutbeam (2000) also differentiates different dimensions of health literacy, including functional, interactive and critical. Harris et al. (2015) summarise this neatly:

Functional literacy is the ability to understand written information and numeracy; interactive literacy is the ability to communicate health needs and interact to address health issues; and critical literacy is the ability to assess the quality and relevance of information and advice to one's own situation (p.3).

However, the vast majority of health literacy research has focussed on promoting functional health literacy, conceived of as ensuring that information is presented to people at a level which corresponds to their reading and numeracy skills and this narrow conceptualisation is ‘reinforced by a health education model that emphasises information giving’ (Harris et al., 2015, p. 4). Moreover, the concept of health literacy has received very little attention in relation to children. The very small body of research that is available echoes the wider literature in its tendency to focus on functional health literacy (Brown et al., 2007, Schmidt et al., 2010, Abrams et al., 2009); (for exceptions see St Leger, 2001; Jain and Bickham, 2014; Paakkari and Paakkari, 2012). Borzekowski (2009) critiques this narrow focus in relation to children specifically:

Although a child or adolescent may be unable to read and define medical texts, that same person might understand healthy behaviors or medical management in his or her home environment and actively participate in decision-making regarding his or her own health care (p. S283).

Acknowledging Freire's central premise that ‘education is not neutral and takes place in the context of people's lives’ (Wallerstein, 1988, p. 381), and drawing upon the Social Studies of Childhood, which sees children as active and reflective in negotiating and renegotiating the information with which they interact (James and Prout 2015), this paper goes beyond this narrow focus on functional health literacy. We mobilise the first two of Nutbeam's (2000) three dimensions of health literacy (accessing and understanding information) to consider how children make health information meaningful in the context of their everyday lives. We do this by focusing upon children's discussions about the relationship between food and health. Our intention is not, therefore, to present children's food-related understandings per se, but rather to consider children's interactions with, and meaning-making in relation to, health information.

2. Methods

2.1. Overview

This paper reports key findings from a qualitative study exploring children's perceptions of food in everyday life and their understandings of the relationship between food and health. The study was carried out in two phases. In phase one, 53 children aged 9–10 attending two schools located in socioeconomically contrasting urban neighbourhoods (School A the more affluent and School B the less affluent) in the North of England took part in interviews and debates in small friendship groups. Children aged 9–10 were chosen in view of an international focus on reducing obesity among children aged under 11 years (World Health Organisation (WHO), 2008). In phase two, a sub-set of eight family case studies were carried out in the home. Children and parents were interviewed separately, to explore in greater depth familial experiences (Curtis et al., 2011) and understandings of the relationship between food and health. This paper draws only upon data generated with children.

2.2. Sampling

A purposive sampling strategy designed to ‘encapsulate a relevant range in relation to the wider universe but not to represent it directly’ (Mason, 2002, p. 121), was adopted for phase one. Census data, eligibility for free school meals and local area knowledge were used to identify two socioeconomically contrasting schools. The head teacher at each school was asked to nominate a class to participate. Aiming to recruit at least 30 children overall, it was envisaged, would represent a sample size which could encapsulate a range of perspectives. Four of the children from School A were of minority ethnicity and all the children from School B were White British. Formal ethical approval for the study was granted from the University of Sheffield Ethics Committee.

To begin to develop a rapport, the first author (the researcher) helped out in both classes for a week prior to the project. The project was explained verbally and through a short information leaflet. Interested children were invited to take a letter and information leaflet home to their parents but, giving priority to children's own consent and in line with a view of children as research subjects in their own right (Christensen and Prout, 2002), parents were only invited to respond if they did not wish their child to participate. At the start of each interview, key project information was revisited and children invited to ask questions before signing a consent form. Children were enthusiastic about participating and only one child declined.

The sampling strategy for phase two was motivated by the aim to include as diverse a sample of experiences and understandings as possible to promote conceptual generalizability of the findings. The target was to recruit a sub-sample of five children and their parents from each school; a practically manageable and meaningful number in terms of both data generation and analysis. Recruitment at School B, however, proved problematic and nine (enthusiastic) children had to be approached in total before gaining four positive responses from parents. Recruitment at School A was much more straightforward; consent was provided by parents of the first four children invited.

2.3. Data generation

Sensitivity to the potential power differentials between child participant and adult researcher and a desire to make the research process as inclusive and enjoyable as possible guided the decision to incorporate task-based activities into the interviews with the children (Punch, 2002). In phase one, to help give them confidence, between 2–3 children worked together in small friendship groups of their own choosing (Hemming, 2008). They took part in semi-structured interviews (n=24) in which they were asked by the researcher to talk through all their 'encounters' with food on a usual school day and on a weekend day. Asking children to narrate their everyday lives can help to ensure children's ideas are grounded in their own experiences and provides fertile ground for the researcher to build upon with further questions (Curtis et al., 2009). Images of a variety of drinks and snacks, chosen by the research team (both quintessentially healthy and unhealthy (Curtis et al., 2011, p. 24), were also shared with the children during the interview and they were invited to supplement these with their own drawings. On a separate occasion, children participated in a debate (n=23), facilitated by the researcher, using ten picture cards with a food-related statement on the underside. Children were invited to choose a card and discuss whether or not it resonated with their own experiences. Statements were created from key issues identified from the literature, for example, parental versus children's responsibility for healthy eating and the idea of ‘balance’. Framing the activity as a debate was intended to encourage the children to move away from the idea that there was a ‘correct’ answer.

The interviews in phase two (n=8) also included two task-based activities. First, children were asked to note down or draw, in two adjacent circles, what they thought a healthy and an unhealthy person would eat. They were then asked to annotate pictures of two children showing how different foods (and different amounts of foods) affect the body. Interviewing children in the home offered the opportunity to work with children outside the school context, where children may be used to a ‘teacher initiation – child response – teacher feedback’ scenario in which children feel they should give a ‘correct’ response (Westcott and Littleton, 2005). In both phases, task-based activities were used to promote enjoyment and stimulate discussion and it was this discussion that constituted the data for analysis. All of the interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. All data were anonymised and children chose their own pseudonyms.

2.4. Analytical strategy

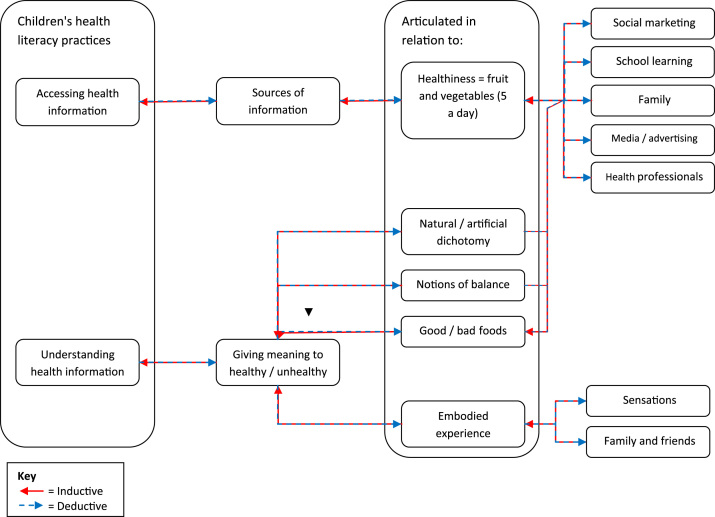

Initial data analysis was carried out in tandem with data generation and used to guide subsequent fieldwork (Richards, 2005). The steps of more formal data analysis followed those outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006, p. 87): familiarising with data; generating initial codes; searching for themes; reviewing themes; defining and naming themes and producing the report. Themes were identified as they ‘captured something important about the data’ (Vaismoradi, Turunen & Bondas, 2013, p. 402) and thus facilitated ‘the identification of a story, which a researcher tells about the data’ (Vaismoradi et al., 2013, p. 403),. Guided by a commitment to privileging children's own ideas, throughout the initial data analysis we sought to ground our evolving interpretations in the data rather than setting out to test a particular theory. The concept of health literacy was later employed as a productive means of opening up the data for critical analysis. This intrinsically ‘messy’ process involved repeatedly moving between the original dataset and the evolving interpretations (Pope et al., 2006). This strategy coheres with Vaismoradi et al.'s description of thematic analysis as comprising both 'description and interpretation, both inductive and deductive' (Vaismoradi et al., 2013, p. 399): analysis was therefore was informed by a process that has been characterised as abductive reasoning (Blaikie, 2010). This proceeds from the identification of concepts, categories and themes in respondents' data to a search of 'relevant literature for ideas about how these social actors' concepts and categories are used in social science' (Ong, 2012, p. 425). The researcher's role is then to understand how these social science concepts resonate with and help to reveal and describe the 'insiders’ view'. Themes were thus refined as we endeavoured to explore children's health literacy practices. An overview of our thematic analysis, with themes and sub-themes, may be found in Fig. 1. Describing and depicting the process of our thematic analysis in detail, in this way, coheres with Sandelowski's notion of trustworthiness, which highlights the importance of 'leaving a decision trail' (Sandelowski, 1986). Throughout the process the software package NVivo8 facilitated data management (coding, retrieval, interrogation and storage) rather than data analysis per se.

Fig. 1.

Thematic analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Accessing health information

Children demonstrated that they accessed (and interacted with) a rich variety of different sources of food-related health information, including social marketing campaigns, the school, the family, the media and advertising, and health professionals. Honing in on children's discussions about the perceived healthiness of fruit and vegetables provides a productive means of capturing some of this variety, though we bring in other illustrative examples where pertinent.

Throughout the fieldwork, children in both School A and B frequently conflated eating healthily with eating fruit and vegetables. Highlighting the potency of recent UK social marketing campaigns promoting the consumption of at least five portions of fruit and vegetables per day, the phrase ‘5 a day’ was uttered on multiple occasions in every research encounter. However, children's discussions demonstrated that this message and indeed the ‘5 a day’ phrase was also articulated through school-based teaching. Children in School B, for example, described their learning for a school assembly for which their teacher had created a class ditty: ‘Live life the healthy way, always eat your 5 a day’. The children enjoyed chanting this to each other and nearly all repeated it in the interviews. Children from both schools also talked about how their parents (firmly) encouraged them to eat fruit and vegetables. Emma's comment, ‘my mum is very strict about eating vegetables’ was typical (Emma, School A). This popular and populist message concerning the importance of fruit and vegetables, therefore, was reinforced for children in both the school and home context.

Advertising was another important source of information regarding the healthiness of fruit and vegetables. Here Harry and Bill discuss the importance of fruit and vegetables as an essential part of a balanced diet:

Harry: Erm well I think it's important to have a balanced diet […] erm quite a lot of fruit and vegetables and two to three erm chocolates or biscuits.

Hannah: And where have you heard about a balanced diet?

Bill: Special K.

Harry and Bill, School A

Bill's reference to Special K is noteworthy as it is a breakfast cereal marketed strongly towards adult women rather than children. It is also strongly marketed as a contributor to a weight-loss diet. Bill does not make clear whether his learning derived from media advertising or from written information on the cereal box. However, overall, children made very few references to written texts and information conveyed orally and visually seemed to resonate much more with them. Abigail's account of reading Recommended Daily Amounts (RDAs) on food labels was therefore unusual:

Yeah so we look on the packets, especially the crisp packets because they say how much you should daily have, calories and stuff, for children and stuff so you know what you should have. Yeah but on some packets it's different. On one packet it says eight hundred for children but then erm I read one, it was like a mushroom pie or something and I read it and it was like less than eight hundred so I, I don't know.

Abigail, School A

With respect to the healthfulness of food, health professionals, though mentioned surprisingly infrequently by the children, constituted a further source of information. A number of children described encounters with health professionals and discussions about eating healthily. Selina, for example, mobilises her doctor's advice about ‘five a day’ to argue that, paradoxically, it is possible to eat ‘too much healthy things’. Her account illustrates the perceived trustworthiness and authority of health professionals as sources of health information:

Yeah if you eat too much erm apples and bananas that can send your teeth rotten and it can send your teeth to wobble and to get things stuck so you can’t get ‘em out […] ‘Cos when I go to the dentist and the doctors […] doctors say ‘Where did you get your toothache from?’ […] and some people say, ‘Well I eat too much healthy things’ so the doctor says, ‘Don’t eat too much just eat erm five a day, like an apple, a pear, an orange, a plum and a raspberry’.

Selina, School B

For Selina, however, the doctor's cautionary words about fruit seem to be at odds with popular messages extolling its virtue. Though the story is perhaps a little confused, it demonstrates that in the context of myriad sources of health information, children are presented with complex and even contradictory messages.

As well as inconsistencies, the data also demonstrate gaps in the health information presented to children in both schools. The importance of eating ‘5 a day’ as one aspect of a nutritious diet, for example, often seemed to be lost in children's discussions. Further, that the five portions should include a variety of fruit and vegetables from across the spectrum or rainbow of colours, a key part of the health promotion campaign (Department of Health (DH), 2010), was generally not recognised by children in either school. Rosalyn's account illustrates this well:

Yeah, my nannan's got two big fruit bowls about that big each! And she just like piles things and then she eats a pear, like a pear three times a day or sommet.

Rosalyn, School B

Here the emphasis is clearly on the number, rather than the variety, of items consumed . Rosalyn's omissions, however, are unsurprising and reflect the filtering of information by adults. In the ditty created by her class teacher, 'Live life the healthy way, always eat your 5 a day', for example, eating 5 a day is characterised as synonymous with eating healthily and there is no mention of consuming a variety of different fruits and vegetables.

Indeed, children from both schools demonstrated their awareness of this filtering process as they critiqued what they perceived to be the one-dimensional nature of school-based teaching about healthy eating. Olivia and Michelle, for example, describe their school Health Week (a week dedicated to promoting healthy lifestyles with focussed teaching, guest speakers, cooking demonstrations and special activities) as ‘sort of for people who don’t do healthy eating’:

Olivia: ‘Cos we’re just gonna take in the same stuff ‘eat healthy, eat healthy’ and then we’re like ‘Oh yeah, I was told that before and before that!’

Michelle: Yeah and we sort of like know it and it's a bit, and it's a bit like, ‘Don’t eat chocolate, eat lots of fruit and veg’.

Olivia and Michelle, School A

Olivia and Michelle critique what they regard as repetitive ('eat healthy, eat healthy') and reductive (chocolate versus fruit and vegetables) school-based teaching around healthy eating. When confronted with inconsistencies, gaps and simplifications in the information that they encounter, children work hard to create meaningful frameworks for understanding the rationale behind the health messages, as we go on to discuss below.

3.2. Understanding health information

A common means through which children from both schools sought to understand and rationalise the 5 a day message was by drawing upon the enduring dichotomy between natural (healthy) and artificial (unhealthy) food. Hermione, for example, uses this reasoning to explain why fruit and vegetables are healthy:

Because there isn’t, because it's grown on trees they haven’t done anything to them they’ve only washed ‘em so they’ve just picked ‘em off tree or from underground if they’re vegetables and then, and then they wash ‘em and do stuff to them and off they go.

Hermione, School B

Children interacted with this rationale in a number of different contexts including the media. Fred and Bradley, for example, demonstrate their active engagement in today's consumer society as they talk about the ‘blue smartie story’ – how Nestlé, the manufacturers of smarties (small sugar coated chocolates), discontinued the blue smartie in 2005 amid criticism over artificial additives but brought it back three years later using a ‘natural’ seaweed derivative to form the distinctive blue colour (Smithers, 2008):

Fred: Sweets have more sugar in them and colouring.

Bradley: ‘Cos sweets have got artificial sugar in them and then chocolate's in a way more natural or something.

Fred: Yeah like the blue smartie was banned for a bit ‘cos it had too much artificial colours in it […] and yeah they’ve brought it back now. Now it hasn’t got anything, all of the chemicals and stuff so it's safe to eat now.

Fred and Bradley, School A

However, children also highlighted that the natural (healthy) versus artificial (unhealthy) dichotomy was not entirely unproblematic. Indeed, although they offered this to justify why 5 a day was the route par excellence to becoming healthy, they realised that this competed with the widely held understanding that sugar, even 'natural sugar', is bad because it causes tooth decay. Katherine and Ali's exchange highlights the tension here:

Katherine: Yeah I would like to learn more about this. It's just, I don't know why the dentist says, 'Now if you have too much fruit then it's bad' because they were saying that fruit's healthy and now they're saying it's bad for you! It's like all the sugars they like dissolve your teeth and they say, they say, 'Oh you can have this special toothpaste'.

Ali: I thought it was good natural sugar?

Katherine: Yeah I thought it was good. Now I think it's bad for you.

Katherine and Ali, School A

An important means by which children from both schools checked, problematised and ultimately made sense of competing information and frameworks of understanding was through their own embodied experience. Olivia, for example, puts forward her own body, a body that consumes chocolate, to mediate and even negate the perceived popular notion (reinforced in the school context) that chocolate is bad:

You could say chocolate is bad for you if you have too much. Because it's not true that chocolate's bad for you because I eat chocolate […] And I’m not completely fat, am I?

Olivia, School A

Her account affords a pertinent example of how children reflected upon the usefulness and resonance of health messages for themselves as individuals. Far from passively absorbing messages, they frequently mobilised their personal, embodied experiences to filter health information in a manner that was meaningful for them.

Indeed, children's discussions illustrated that they thought that physical, embodied sensations were reliable indicators of the healthiness of foods and of when they had eaten enough (or too much). Rosalyn, for example, reasons, ‘I think melted chocolate is more bad for you because warm chocolate makes you feel sick’ (School B). Similarly, in the context of talking about whether he usually eats puddings, Nick says: ‘[…] sometimes I just get full and let it go down’ (School A). Here then Nick describes how he responds to his body's cues when deciding whether to have pudding. More frequently, however, children talked about how they felt after eating too much. Caitlin, for examples, says:

Yeah you might get a headache and you get tummy ache and you have to go to bathroom for a bit and just sit down and if you’ve got a chair in bathroom and I just sit there like that.

Caitlin, School B

Children's reliance on and trust in their embodied experiences was also particularly evident in their critiques of the aide memoires for a ‘balanced diet’ promoted at school, which they thought contained too little sugar (which they considered to be a vital source of energy) for their bodies’ needs. Ava and Emma, for example, critique the ‘balanced wheel’ (a visual representation of different food groups and the proportions we should eat them in to have a ‘balanced diet’):

Ava: But I think you need a bit more sugar.

Emma: Because they only had that much! (Gestures tiny amount)

Ava: Yeah and there was so much fruit and veg it wouldn't be good to eat that much fruit and veg and only that much sugar!

[…]

Emma: Yeah 'cos they make it a big thing that it's good to eat fruit but they never thought that sometimes you might need to eat quite a bit of sugar if you want to get your energy going […]

Hannah: Oh right and when you say 'they', who do you mean?

Emma: Teachers and parents, all people like that.

Ava and Emma, School A

Ava and Emma critique information which is being presented to them as fixed, scientific and non-negotiable because their embodied experience tells them that there is no one, fixed healthy diet but rather individually mediated requirements.

Conversations with family and friends were pivotal in helping children to relate potentially abstract information to their own lives and to trust their own embodied experiences. In one of the friendship group interviews in School A, for example, a group of boys talked enthusiastically about the role of food as a fuel for exercise. They constructed joint accounts, adding to and relating to each other's stories and talked about how their membership of sports teams motivated them to be healthy. Fred and Bradley's conversation illustrates this:

Fred: I always have a football match on a Sunday morning so I always have loads of healthy stuff on like Saturday night.

[…]

Bradley: There are these mixes where you can have like pasta and like some, ‘cos pasta's good for you –

Fred: ‘Cos it's got a lot of carbs in it.

Bradley: Yeah and you can have, and my mum makes it where you put like vegetables and meat in it so it's like five a day erm, you’ve got meat in it. And I have it before training.

Bradley and Fred, School A

This group of boys were very keen to convey their enjoyment of different vegetables. They thought that this was unusual for boys of their age and emphasised their group identity as ‘sporty, successful boys’.

As well as providing opportunities to relate health information to their own lives, conversations with family and friends also helped children to question the relevance of apparently universal health information for their individual bodies and energy requirements. Katherine, for example, describes discussions with her father about how many calories she will burn at swimming. Such conversations seemed to be very much part of everyday life for Katherine and, importantly, they give her the confidence to reject the popular health message that sugar and sweet things are bad on the basis that she needs sugar for energy in order to participate in sport:

My motto for lunch and dinner is 'No meal is complete without a pudding'. I love my puddings. […] I usually do (have puddings) 'cos I do lots of swimming like four times a week like hard swimming 'cos I'm in a team, it's Junior Olympics 1, 2.

Katherine, School A

Similarly, Elizabeth rejects the popular notion that fat is bad as she describes her personal efforts to gain weight by changing what she eats:

Yeah I like to eat too much fat because I wanna get fatter! (whines) My mummy calls me 'skinny ribs' (funny voice) and I don't like it! (funny voice) And they also say I'm skin and bones.

Elizabeth, School B

Elizabeth's phrase 'too much fat' highlights the incongruence between what she thinks is generally healthy and what she believes her body needs. Conversations in the home, then, have led Elizabeth to critique the relevance of universal healthy eating messages for her own body. Just as Katherine refers to familial conversations before introducing her alternative pudding motto, Elizabeth clearly prioritises her mother's injunction to grow a bigger body (which she interprets as eating more fat) even though this jars with commonly-held notions of healthy eating. In this way, children privilege their own embodied experiences and understandings constructed through interactions with families and peers. Children's embodied experiences help them to bridge the gap between being able to appreciate, remember and reiterate health information and translating this information into something that is personally meaningful.

4. Study strengths and limitations

The study from which these findings derive sought to focus on children's own views, which have been relatively underexplored in the context of health promotion. The positive and productive research relationships forged during the study allowed the generation of in-depth data. Opportunities afforded by the research design for children to elaborate on and reconsider their ideas by working with them on two and sometimes three occasions, the inclusion of task-based activities and children's ability to work in friendship groups in schools all helped to foster a positive environment in which children could reflect upon and share their ideas. Nevertheless, there are inevitable limitations to such a study that need to be acknowledged. Fifty-three children participated and the study, only four of whom were from minority ethnic groups and no claim for empirical generalizability can therefore be made. Furthermore, following Mason (2002) we acknowledge that explanations do not simply emerge from the data and different interpretations could be crafted by applying different theoretical lenses (p.149). Nevertheless, by carefully articulating the study context and by seeking to lay over interpretations onto data 'without doing violence to them' (Richards and Richards, 1994), the findings presented in this paper accord with Mason's notion of theoretical generalisability in which the 'detailed and holistic explanation of one setting, or set of processes, [can] frame relevant questions about others' (Mason, 2002, p. 196).

5. Discussion

Child health research has largely been informed by traditional models of child development in which children progress through predictable and universal stages of development (McIntosh et al., 2013, p. 4). Within this framing, didactic teaching of knowable facts is prioritised and children characterised as sponges waiting to be filled with information (Evans et al., 2011; St Leger, 2001). Although a small, yet growing body of research focuses on exploring children's own health-relevant understandings and practices (for example, Christensen (2004), Mayall (1998), McIntosh et al., (2013) and Fairbrother etal. (2012, 2016)), the ways in which children interact with health messages and how these messages do (or do not) become meaningful for children in their everyday lives, represents a significant gap in the literature (Borzekowski, 2009). The notion of health literacy, how people access, understand and use health information (Nutbeam, 2000) can open up for critical analysis the ways in which children make meaning in relation to health messages. In this paper, honing in on how children access and understand health information (the first two dimensions of Nutbeam's, (2000)) conceptualisation of health literacy) has provided a productive, if not entirely unproblematic, analytical framework for understanding how children make meaning with respect to the relationship between food and health.

Exploring how children access health information has helped to provide a picture of the myriad sources with which children interact. In sharp contrast to traditional conceptions of health promotion, which depict health promotion as the predominant source of health information (St Leger, 2001, Wallerstein, 1988), children's accounts attest to the wide variety of different and sometimes competing food-related information resources, which children access. As well as the school and the home, well-recognised resources for children's learning, children's accounts show that they access information in the wider social context, such as advertising aimed at adult audiences and contemporary media stories (Buckingham, 2000, Buckingham, 2013). Further and significantly, while their discussions regarding the healthiness of fruit and vegetables certainly show that children can and do appreciate, remember and reiterate the information given to them, they also demonstrate inconsistencies, gaps and simplifications in the information they access. Consequently, children have to work hard to piece together, prioritise or reject fragments of information in order to create broader, more comprehensive frameworks of understanding that work for them in their everyday lives.

Exploring how children form understandings, the second stage in Nutbeam's (2000) health literacy process, has facilitated the creation of a nuanced, complex picture of meaning making engaged in by children. Nutbeam's (2000) dimensions of critical and interactive literacy have particular resonance for the data explored. The way in which children mobilised their own embodied experiences to check and sometimes problematise the health information with which they interacted represents a pertinent example of critical literacy: 'the ability to assess the quality and relevance of information and advice to one’s own situation' (Harris et al., 2015, p. 3). Their critique of dominant messages (like, for example, chocolate is bad) when their own bodies manifest that this is not always the case provides compelling evidence of how children engage in health literacy as a way of assessing the meaningfulness of health information for their everyday lives (Wallerstein, 1988). In this way, the data illustrate how children take health information and apply it to their specific, individual circumstances (Ishikawa et al., 2008), contextualising it in relation to their own health (Rubinelli, Schulz & Nakamoto, 2009; Wallerstein, 1988). Chinn (2011) highlights the relevance of such critical thinking skills in what she describes as an 'age of information overload' where individuals are forced to navigate through a wealth of often inconsistent and competing information and develop their own ideas. As Chinn (2011) suggests, such tactics resemble Lupton's (1997) description of the 'ideal health consumer' in contemporary society: a consumer who is 'sceptical of expert opinions, reflexive, autonomous, evaluating information in terms of personal benefit […]' (Chinn, 2011, p. 62). Such a characterisation is clearly in sharp contrast to dominant conceptualisations of children as empty vessels or neutral sites (Wallerstein, 1988, p. 381). The health promotion picture is thus much more complicated than the simple transmission of knowledge and values from adults to children (St Leger, 2001).

Children's frequent references to conversations with peers and families also resonate closely with Nutbeam's (2000) dimension of interactive health literacy: the ability to communicate health needs and interact to address health issues (Harris et al., 2015, p. 3). Their accounts showed that such conversations facilitated children's engagement in critical literacy. Through discussing the relevance (or otherwise) of competing health information children were able to assess its meaningfulness for themselves. Here, however, Nutbeam's conceptualisation of health literacy as a personal skill belonging to a particular individual fails to do justice to the findings presented. Katherine's and Elizabeth's accounts, for example, attest not so much to their own abilities to communicate with their families but to the existence of regular opportunities to discuss health information with their families. In this respect, the data resonates much more closely with so-called 'second wave' health literacy research (Papen, 2009, Nutbeam, 2008), which encapsulates multiple literacies ‘reading and writing, speaking, e-literacy, political literacy’ (Chinn, 2011, p. 61), for example. In particular, researchers within the New Literacy Studies, analyse literacy not as a ‘set of purely technical coding and decoding skills’ but as a ‘social practice’ (Chinn, 2011, p. 61), 'something people do in their everyday lives' (Pahl and Rowsell, 2012, p. 7), in interaction with those around them (Papen, 2009, p. 13). Interactions may occur at both a micro level (for example, within the family) and a more macro level (for example, within a whole community). In this way, Barton and Hamilton (1998) argue, 'literacy becomes a community resource, realised in social relationships rather than a property of individuals' (p.13). As Chinn contends, therefore, the focus moves from assessing ‘absolute differences in literacy, as an individual attribute’ to exploring ‘how people with a range of relevant personal and social resources’ (Chinn, 2011, p. 61), practise literacy in their everyday lives. Indeed, work within the New Literacy Studies has shown that interactions with peers, family (Compton-Lilly, 2006, Kendrick, 2005, Levy, 2008) and community (Brice Heath, 1983) are pivotal in emerging literacy practices. This practice-based, relational approach is compelling for this study and represents an important extension to Nutbeam's (2000) original notion of individualised health literacy. It also contrasts with Christensen's (2004) characterisation of the child as a health-promoting actor, which although situated within the broader family and society, focuses on the child's personal attributes including health-related knowledge, skills and competencies with a view to the child developing 'independent agency in relation to their own (and others') health' (p. 379). Children's frequent references to conversations with family and friends suggest, rather, that in contrast to 'independent agency', children's engagement in critical and interactive health literacy practices should be seen very much as embedded within their networks of social relationships and as community rather than individual practices. In this way the data cohere closely with Freire's call for health education to value the ‘collective knowledge that emerges from a group sharing experiences and understanding’ (Wallerstein, 1988, p. 382), rather than focusing on knowledge as a product of experts ‘inculcating their information’ (Wallerstein, 1988, p. 382).

The New Literacy Studies' emphasis on literacy as inherently social also helps to move away from a notion of health literacy as a fixed set of skills. Instead, the focus on practices draws attention to the routine elements which make up day-to-day life (Morgan, 2011). Within this, literacy practices, it is argued, represent shifting social practices contingent on identities and changing according to social and cultural context. Here then, the emphasis is on meaningfulness in the context of lived experience. Researchers working within this approach have, for example, critiqued phonics-based teaching in which young children are asked to sound out nonsense words as irrelevant to literacy because it tries to take a lived practice out of its social context. This kind of approach also renders a broad, generic framework like 'the balanced plate' as irrelevant - here information is presented as fixed, universal and detached from the lived experience of individual bodies. Children's emphasis on the centrality of their embodied experiences attests to this.

6. Conclusion

This paper has sought to illustrate some of the complexity of children's meaning-making with respect to health information by focussing upon the relationship between food and health. Looking through the lens of health literacy (and integrating ideas from New Literacy Studies) has helped to illuminate the messy and negotiated character of this meaning-making, with important implications for health education policy and practice. That children do not passively absorb health messages but rather work with them (through their engagement in critical and interactive health literacy) to create meaning indicates that presenting children with simple, one-dimensional health messages only serves to emphasise gaps in understanding which children have to navigate. It is vitally important, then, for health education to work towards conveying a more holistic picture of the complexities and interrelationships between different aspects of a healthy diet (and indeed health in general) in a coherent and consistent way. Starting with children's own ideas and understandings and recognising that they are already active health literacy practitioners, consistent with insights from community development and adult education literature (St Leger, 2001, Wallerstein, 1988, Harris et al., 2015), will help lay the foundations for such an approach. The school setting may play an important role in drawing together and working with children's understandings (developed through multiple sources and in conjunction with those around them) and embodied experiences and encouraging them to critically appraise health messages (St Leger, 2001). The trust that children have in their bodies might be accommodated, for example, by introducing the notion of balancing energy input and output and posing a question like ‘What do you think your body needs to get through a long run?’. This approach would help to negotiate a productive context for the cross-pollination of ideas and the co-production of knowledge and insights. Schools, therefore, could prioritise the provision of opportunities for engaging in and encouraging interactive and critical health literacy practices, rather than functioning predominantly, as St Leger argues, as fonts of fixed information and guidance (St Leger, 2001). Such a framing necessitates viewing children as ‘equals’ and ‘co-learners’ in the creation of knowledge and coheres very closely with Freire's notions of empowering education (Wallerstein, 1988, p. 382). Indeed, facilitating the development of 'communities of (health literacy) practice' (Wenger, 1998) in and beyond the school context is likely to be a much more sustainable and cost-effective approach to health education than the didactic transmission of knowledge.

Mobilising and bringing together insights from the Social Studies of Childhood, health literacy and New Literacy Studies also offers exciting possibilities for exploring diverse experiences. How children's interactions with health messages might vary according to ethnicity, socioeconomic position, gender, digitisation and indeed the globalisation of children's everyday lives represents fertile ground for future research. Further, while this study has honed in on how children access and understand health information, more work is now needed which explores how the ways in which children make health information meaningful relate to how they use this information in the context of their everyday lives.

Contributor Information

Hannah Fairbrother, Email: h.fairbrother@sheffield.ac.uk.

Penny Curtis, Email: p.a.curtis@sheffield.ac.uk.

Elizabeth Goyder, Email: e.goyder@sheffield.ac.uk.

References

- Abrams A. Health literacy and children: Introduction. Paediatrics. 2009;124(3):S262–S264. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1162A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AdHoc Committee on Health Literacy for the Council of Scientific Affairs AMA Health literacy: Report of the council on scientific affairs. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;281(6):552–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler P.A., Adler P. Rutgers University Press; New Brunswick: 1998. Peer power: Preadolescent culture and identity. [Google Scholar]

- Bankson H.L. Health literacy: An exploratory bibliometric analysis, 1997–2007. Journal of the Medical Library Association. 2009;97(2):148–150. doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.97.2.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton D., Hamilton M. Routledge; London and New York: 1998. Local Literacies: Reading and writing in one community. [Google Scholar]

- Blaikie N. 2nd ed. Polity; Cambridge, MA: 2010. Designing social research: The logic of anticipation. [Google Scholar]

- Blair M. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2010. Child Public Health. [Google Scholar]

- Borzekowski D. Considering Children and Health Literacy: A Theoretical Approach. Paediatrics. 2009;124:S282–S288. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1162D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady G. Wiley-Blackwell; Oxford: 2015. Children, Health and Well-being: Policy Debates and Lived Experience. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Brice Heath S. Cambridge University Press; New York and Cambridge: 1983. Ways with words: Language, life and work in communities and classrooms. [Google Scholar]

- Brown S., Teufel J., Birch D. Early adolescent perceptions of health and health literacy. Journal of School Health. 2007;77(1):7–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham D. Polity; Cambridge: 2000. After the death of childhood: Growing up in the age of electronic media. [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham D. Polity; Cambridge: 2013. Media education: Literacy, learning and contemporary culture. [Google Scholar]

- Chinn D. Critical health literacy: A review and critical analysis. Social Science and Medicine. 2011;73:60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen P. The health-promoting family: A conceptual framework for future research. Social Science and Medicine. 2004;59(2):377–387. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen P., Prout A. Working with ethical symmetry in social research with children. Childhood. 2002;9(4):477–497. [Google Scholar]

- Compton-Lilly C.F. Identity, childhood culture, and literacy learning: A case study. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy. 2006;6(1):57–76. [Google Scholar]

- Corsaro W.A. Joseph Henry Press; Washington: 2003. 'We're friends, right?': inside kids' cultures. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis P. ‘She's got a really good attitude to healthy food… Nannan's drilled it into her’: Inter-generational Relations within Families. In: Jackson P., editor. Changing Families, Changing Food. Palgrave Macmillan; Basingstoke: 2009. pp. 77–92. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis P. Children's snacking, children's food: food moralities and family life. In: Punch S., editor. Children's food practices in families and institutions. Routledge; London: 2011. pp. 65–76. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health (DH). (2010) School Fruit and Vegetable Scheme [online] Available from: Available from: 〈http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publichealth/Healthimprovement/FiveADay/FiveADaygeneralinformation/DH_4002149〉 (accessed 8.09.15).

- Evans B. 'Change4life for your kids': embodied collectives and public health pedagogy. Sport, Education and Society. 2011;16(3):323–341. [Google Scholar]

- Fairbrother, H., Curtis, P., Goyder, E., 2012. Children's understanding of family financial resources and their impact on eating healthily. Health and Social Care in the Community 20 (5), 528–536, 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2012.01070.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2016.Fairbrother, H., Curtis, P., Goyder, E., 2016. Where are the schools? Children, families and food practices. Health and Place 40, 51–57, 10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Freire P. Penguin Books; London: 1993. Pedagogy of the oppressed. [Google Scholar]

- Graham H., Power C. Health Development Agency; London: 2004. Childhood disadvantage and adult health: a lifecourse framework. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris J. Can community-based peer support promote health literacy and reduce inequalities? A realist review. Public Health Research. 2015;3:3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemming P. Mixing qualitative research methods in children's geographies. Area. 2008;40(2):152–162. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (IoM) (2004). Health Literacy: a prescription to end confusion. Washington DC, National Academic Press.

- Ishikawa H. Measuring functional, communicative, and critical health literacy among diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(5):874e879. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain A., Bickham D. Adolescent health literacy and the Internet: challenges and opportunities. Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 2014;26(4):435–439. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James A., Prout A., editors. Constructing and reconstructing childhood: Contemporary issues in the sociological study of childhood. Routledge; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kendrick M. Playing house: A sideways glance at literacy and identity in early childhood. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy. 2005;5(1):5–28. [Google Scholar]

- Levy R. `Third spaces´ are interesting places; applying `third space theory´ to nursery-aged children´s constructions of themselves as readers. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy. 2008;8(1):43–66. [Google Scholar]

- Lupton D. Consumerism, reflexivity and the medical encounter. Social Science and Medicine. 1997;45(3):373e381. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00353-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason J. Sage; London: 2002. Qualitative researching. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews S.H. A window on the 'new' sociology of childhood. Sociology Compass. 2007;1(1):322–334. [Google Scholar]

- Mayall B. Towards a sociology of child health. Sociology of Health and Illness. 1998;20(3):269–288. [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh C. Young children's meaning making about the causes of illness within the family context. Health. 2013;17(1):3–19. doi: 10.1177/1363459312442421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan D. Palgrave Macmillan; Basingstoke: 2011. Rethinking family practices. [Google Scholar]

- Nutbeam D. Health literacy as a public health goal: a challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promotion International. 2000;15(3):259–267. [Google Scholar]

- Nutbeam D. The evolving concept of health literacy. Social Science and Medicine. 2008;67(12):2072–2078. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong B.K. Grounded Theory Method (GTM) and the Abductive Research Strategy (ARS): a critical analysis of their differences. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2012;15L5:417–432. [Google Scholar]

- Paakkari L., Paakkari O. Health literacy as a learning outcome in schools. Health Education. 2012;112(2):133–152. [Google Scholar]

- Pahl K., Rowsell J. 2nd Ed. Sage; London: 2012. Literacy and Education: The New Literacy Studies in the Classroom. [Google Scholar]

- Papen U. Literacy, learning and health – A social practices view of health literacy. Literacy and Numeracy Studies. 2009;16(2):19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Parton N. ‘Every Child Matters’: the shift to prevention whilst strengthening protection in children's services in England. Children and Youth Services Review. 2006;28(8):976–992. [Google Scholar]

- Pope C. Analysing Qualitative Data. In: Pope C., Mays N., editors. Qualitative research in healthcare. Blackwells; Oxford: 2006. pp. 63–81. [Google Scholar]

- Prout A. Routledge; London: 2005. The future of childhood: towards the interdisciplinary study of children. [Google Scholar]

- Punch S. Research with Children: The Same or Different from Research with Adults? Childhood. 2002;9(3):321–341. [Google Scholar]

- Richards L. Sage; London: 2005. Handling qualitative data: a practical guide. [Google Scholar]

- Richards L., Richards T. From filing cabinet to computer. In: Bryman A., Burgess R.G., editors. Analysing Qualitative Data. Routledge; London: 1994. pp. 146–172. [Google Scholar]

- Rubinelli S., Schulz P.J., Nakamoto K. Health literacy beyond knowledge and behaviour: letting the patient be a patient. International Journal of Public Health. 2009;54:307–311. doi: 10.1007/s00038-009-0052-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. The problem of rigor in qualitative research. Advances in Nursing Science. 1986;8:27–37. doi: 10.1097/00012272-198604000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt C. Health-related behaviour, knowledge, attitudes, communication and social status in school children in Eastern Germany. Health Education Research. 2010;25(4):542–551. doi: 10.1093/her/cyq011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Search Institute (2016). 40 Developmental Assets for Young People. Available from: 〈http://www.search-institute.org/content/40-developmental-assets-adolescents-ages-12-18〉 (accessed March 2016)

- Smithers R. The Guardian; 2008. Smarties manufacturer brings back the blues. (11.02.08) [Google Scholar]

- St Leger L. Schools, health literacy and public health: possibilites and challenges. Health Promotion International. 2001;16(2):197–205. doi: 10.1093/heapro/16.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF . UNICEF; New York: 2014. The State of the World's Children in 2014 in Numbers. Every Child Counts – Revealing disparities, advancing children's rights. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (UN), (2015). Open Working Group proposal for Sustainable Development Goals 〈https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdgsproposal〉

- United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), (1989). Available from: 〈http://www.unicef.org.uk/UNICEFs-Work/UN-Convention/〉

- Vaismoradi M., Turunen H., Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing Health Sciences. 2013;15:398–405. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N. Empowerment education: Freire's ideas adapted to health education. Health Education Quarterly. 1988;15(4):379–394. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger E. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1998. Communities of practice: Learning, meaning and identity. [Google Scholar]

- Westcott H., Littleton S. Exploring meaning in interviews with children. In: Greene S., Hogan D., editors. Researching Children's Experience: Approaches and Methods. Sage; London: 2005. pp. 141–157. [Google Scholar]

- Wills W.J. Exploring the limitations of an adult-led agenda for understanding the health behaviours of young people. Health and Social Care in the Community. 2008;16(3):244–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2008.00764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation (WHO) WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2008. School policy framework. Implementation of the global strategy on diet, physical activity and health. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation (WHO), (2015). Child Health. Available from: 〈http://www.who.int/topics/child_health/en/〉