Abstract

The spiritual health of adolescents is a topic of emerging contemporary importance. Limited numbers of international studies provide evidence about developmental patterns of this aspect of health during the adolescent years. Using multidimensional indicators of spiritual health that have been adapted for use within younger adolescent populations, we therefore: (1) describe aspects of the perceptions of the importance of spiritual health of adolescents by developmental stage and within genders; (2) conduct similar analyses across measures related to specific domains of adolescent spiritual health; (3) relate perceptions of spiritual health to self-perceived personal health status. Cross-sectional surveys were administered to adolescent populations in school settings during 2013–2014. Participants (n=45,967) included eligible and consenting students aged 11–15 years in sampled schools from six European and North American countries. Our primary measures of spiritual health consisted of eight questions in four domains (perceived importance of connections to: self, others, nature, and the transcendent). Socio-demographic factors included age, gender, and country of origin. Self-perceived personal health status was assessed using a simple composite measure. Self-rated importance of spiritual health, both overall and within most questions and domains, declined as young people aged. This declining pattern persisted for both genders and in all countries, and was most notable for the domains of “connections with nature” and “connections with the transcendent”. Girls consistently rated their perceptions of the importance of spiritual health higher than boys. Spiritual health and its domains related strongly and consistently with self-perceived personal health status. While limited by the 8-item measure of perceived spiritual health employed, study findings confirm developmental theories proposed from qualitative observation, provide foundational evidence for the planning and targeting of interventions centered on adolescent spiritual health practices, and direction for the study of spiritual health in a general population health survey context.

Keywords: Adolescent, Child development, Gender, Nature, Spiritual health, Spirituality

Highlights

-

•

Spiritual health is recognized as one of four domains of health.

-

•

Few quantitative studies exist describing patterns of spiritual health in child populations.

-

•

We employed a series of items that describe perceptions of the importance of spiritual health and its domains in adolescents.

-

•

We demonstrated strong developmental and gender-based patterns that were consistent across countries and cultures.

-

•

Perceptions of the importance of spiritual health appear to be linked with adolescent health outcomes.

Introduction

Spirituality is a broad concept that relates to wisdom and compassion (Miller & Nakagawa, 2002), the experience of wonder and joy in life (Bone, Cullen, & Loveridge, 2007), moral sensitivities (Hay & Nye, 1998) and the idea of “connectedness” (Palmer, 2009, Hay and Nye, 1998). It relates to a range of experiences, from those that are life affirming to those that are painful (Eaude, 2003). Further, spirituality has been described as “the intrinsic human capacity for self-transcendence in which the individual participates in the sacred—something greater than the self” (Yust, Johnson, Sasso, & Roehlkepartain, 2006). Spiritual health has been recognized as a fourth dimension of health (along with social, emotional/mental and physical domains) (Dhar et al., 2011, Dhar et al., 2013, Hawks et al., 1995, Miller and Thoresen, 2003, Udermann, 2000), and we understand it to be under this broader construct of spirituality.

While the spiritual dimension of health has re-emerged as part of an important discussion in health literature, there is little consensus in the literature as to a concise definition (Hawks et al., 1995, Vader, 2006). Because this field is evolving, we argue that it is premature to propose a single, succinct definition as being able to capture this multi-dimensional and somewhat elusive construct. However, in order to facilitate dialogue, we propose the following working definition. Spiritual health is a dimension of health that entails a condition of spiritual well-being. This is a "way of being" that involves some capacity for awareness of the sacred qualities of life experiences and is characterized by connections in four domains: (1) connections to self, (2) others, (3) nature, and (4) with a sense of mystery or larger meaning to life, or whatever one considers to be ultimate. Spiritual development is also important to consider. It relates to the developmental process of nurturing the human capacity for spiritual health. Benson, Roehlkepartain, and Rude (2003) describe it as the “developmental ‘engine’ that propels the search for connectedness, meaning, purpose, and contribution” (Benson et al., 2003, p. 205). While our study has the narrow focus of describing developmental patterns related to perceptions of the importance of spiritual health, it belongs in a larger and emerging academic conversation about both spirituality and spiritual development.

There are possible benefits to including spiritual health as part of a holistic conceptualization of adolescent health and well-being. Such thinking considers the health of children as dynamic and integrated whole human beings as opposed to using a more compartmentalized approach. In particular, this is consistent with the teachings of many Indigenous cultures and also reflects a growing body of contemporary research in more secular societies that demonstrates the importance of spiritual health to adolescent populations (King et al., 2013, Roehlkepartain et al., 2006). It is also in keeping with principles laid out in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, which outlines a child׳s right to a sense of spiritual well-being and refers explicitly to these spiritual rights in four of its articles (UNICEF, 1989). To illustrate, the Convention states that the child “be given opportunities… to enable him [sic] to develop physically, mentally, morally, spiritually and socially in a healthy and normal manner and in conditions of freedom and dignity” (UNICEF, 1989).

Research in the field of child spiritual health is challenged by the multidisciplinary nature of the concept and the fact that there are subtle differences in language and definitions applied across disciplines, and approaches to presentation of findings. Child spirituality has been referred to as a concept that can be “described but that is very difficult to define” (Eaude, 2003). There is some agreement that it involves some capacity for awareness of the sacred qualities of life experiences, and that these are especially connected to being in relationship. This is typically expressed (as per our working definition) in the four relational domains. This is in keeping with conceptual frameworks developed by scholars including Fisher (2011) and Hay and Nye (1998).

In addition, it is important to distinguish between the concepts of spirituality and religiosity. While religious traditions can sometimes be vehicles for spiritual experience and growth, child spirituality has been viewed as a more universal construct, one that is not dependent on, or contained by, religious expression (Crompton, 1999). Many studies on adult populations have explored spirituality as separate from religiosity, and identify these experiences as “spiritual-but-not-religious” (“SBNR”) (Schnell, 2012), “non-religious spirituality” (Jirásek, 2013, Hyland, Wheeler, Kamble, & Masters, 2010), “atheistic spirituality” (Nolan, 2009), and “humanist spirituality” (Kaufman, 1987). While this may also be a common experience in child populations, because of some natural overlaps between spirituality and religion, it is more difficult for children—especially younger children who have not yet developed the ability to think abstractly—to be able to clearly distinguish spirituality and religiosity as separate concepts (Crompton, 1999). Our study is based on the assumption that while many children experience spirituality and religion in similar contexts, children do not need to be religious in order to be spiritual.

Spirituality-based practices provide one foundation for health and its promotion (Lippman and Keith, 2006, Sallquist et al., 2010). In educational and clinical settings, examples include interventions that focus on exposures to nature (Louv, 2005, Louv, 2012), and techniques such as self-quieting exercises and meditation and related mindfulness exercises (Simkin and Black, 2014, Shonin et al., 2012). Such practices are becoming common in many schools, hospitals, and outpatient settings (Blaney and Smythe, 2014, Thompson and Gauntlett-Gilbert, 2008). Engagement in spiritual health practices has long been recognized in pastoral settings where care is provided for situations involving serious illness and death (Feudtner et al., 2003, Pendleton et al., 2002). An emerging body of research now examines the merits of spiritual health and care not only for young people in health crisis and at end-of-life, but for those nearer to the beginning. This contemporary surge in interest can perhaps be attributed to a number of studies suggesting links between spirituality and positive mental health (Eaude, 2009), happiness (Holder, Coleman, & Wallace, 2008), and resilience among children (Smith, Webber, & DeFrain, 2013).

More internationally, despite strong interest in spiritual health as an important dimension of the health of children, as well as the United Nations mandate to address such spiritual needs (UNICEF, 1989), the international research base in the peer-review domain is limited, and there is a need for further evidence to understand the views of younger children about their own spiritual health (Benson et al., 2003, Houskamp et al., 2004). Descriptions of developmental and gender-based patterns of spiritual health across countries and cultures would be especially helpful as much of the existing evidence is based on qualitative research paradigms (e.g., Hay & Nye, 1998) or theoretical discussions (e.g., Eaude, 2009). Adolescence is a unique developmental phase, and is distinct from childhood (Caskey & Anfara, 2007). Consequently, intentional study of how adolescents perceive spirituality is worthy of consideration.

We had the opportunity to conduct a quantitative study of the spiritual health of adolescents through our involvement in the cross-national Health Behaviour in School-aged Children study, or HBSC (Freeman et al., 2011). This longstanding study involves researchers in some 43 countries or regions and seeks to understand adolescent health and its contextual determinants. In its most recent cycle (2013–2014), a series of spiritual health measures were available to countries as a new optional set of items. We used this opportunity in order to: (1) describe aspects of perceptions of the importance of spiritual health of young people by developmental stage within genders and across the six countries; (2) conduct similar analyses but within four specific domains of spiritual health; (3) relate perceptions of the importance of adolescent spiritual health to self-perceived personal health status. Our intentions were to explore the assessment of spiritual health within a general adolescent health survey context, to evaluate the consistency of suspected developmental and gender-based patterns of adolescent spiritual health experiences inferred from existing theories (Hay and Nye, 1998, Fisher, 2011), and to provide evidence that might inform the eventual planning and targeting of spiritual health interventions applied to adolescents within a diversity of health, educational and home settings.

Methods

Study populations and procedures

Countries involved in this cross-national study were as follows: Canada, the Czech Republic, England, Israel, Poland and Scotland. School-based anonymous surveys were conducted in each country during the academic year 2013–2014 according to a common research protocol (Currie et al., 2012). Our national research teams surveyed students to produce representative national estimates for 11–15 year-olds. Classes within schools were selected with variations in sampling criteria permitted to fit country-level circumstances. The samples included children across each year of this age range, although in some countries the questions were only asked of older age groups (ages 13–15 years). While some national samples were developed to be self-weighting, in others (e.g., Canada), standardized weights were created to ensure representativeness. Country teams obtained approval to conduct the survey from the ethics review board or equivalent regulatory body associated with the institution conducting each respective national survey. Participation was voluntary, and consent (explicit or implicit) was sought from school administrators, parents, and participating students as per national human subject requirements. At the student-participant level, response rates varied by country and were >80% at the school level, and >70% at the individual student level.

Measures

Adolescent spiritual health

The spiritual health module consisted of eight questions adapted (for age-appropriate literacy and brevity) from Fisher׳s Spiritual Well-being scale for secondary students (Gomez & Fisher, 2003). Two items were asked for each of the four standard domains. Students responded to these questions with one of five response categories ranging from 1—“not at all important” to 5—“very important.” (N.B. response categories in Israel varied from the standard protocol, and varied from 1—“not at all important” to 4—“very important”). The items asked students to identify at what level they think it is important to: “feel that your life has meaning or purpose”; “experience joy (pleasure, happiness) in life” (connections to self); “be kind to other people”; “be forgiving of others” (connections to others); “feel connected to nature”; “care for the natural environment” (connections to nature); “feel a connection to a higher spiritual power”; “meditate or pray” (connections to the transcendent). A priori, our hope was that the eight items could be examined individually, by domain, and then potentially be combined into a multidimensional scale. Use of an abbreviated (8-item) version of a scale was dictated by our absolute requirement to keep this instrument short and succinct, to minimize response burden, especially in very young adolescents.

Refinement of the spiritual health module for young adolescents

When the original version of this module was administered to a young adult population, Cronbach׳s alpha values for the items included in the four domains ranged from 0.72 to 0.86, with an overall value of 0.78 (Wallace, 2010). When the scale in its original form was first introduced to HBSC, concerns expressed included its length for inclusion on a general population health survey, and its level of literacy for use with much younger adolescents (11 years). This was confirmed in initial focus group testing in Canada. Therefore, in an adapted version of the module we retained the 8 items (2 per domain) with the highest factor loadings from the Wallace (2010) study. We then tested this 8-item module both quantitatively (n=630) and qualitatively (n=21) in Scotland and Canada (n=48) in 2013. A Cronbach׳s alpha value of >0.80 for the eight items was found in initial reliability testing. This round of focus group work suggested that two items were not clearly understood by young people during these pilots, particularly in very young adolescents. Hence, the items were re-worded based upon the recommendations of these same young people, to improve face validity.

We next went on to test this abbreviated and refined version of the module using the Canadian HBSC sample (n=25,567), considering solutions with up to four factors. Principal components analyses involved oblimin rotation (which assumes correlation between items). Findings best supported a four-factor structure where the revised scale items loaded highly (each>0.80) and according to the original four domains. This was further supported by a maximum likelihood goodness of fit test (p=0.10) and observed Cronbach׳s alpha values of >0.80 for each of the four domains. Confirmatory analyses too supported a four-factor solution with fit statistics within acceptable ranges (RMSEA 0.06, SRMR 0.02, AGFI 0.97). This supported the conduct of analyses with the abbreviated 8-item scale but at the level of the four original domains. However, based on the original theoretical concept that would also support a composite measure of spiritual health, we also combined the 8 items into a single multi-dimensional scale, for exploratory purposes only (N.B., please see the discussion section surrounding our planned use of this scale, moving forward).

General health status

Each respondent rated their personal health status: “Would you say your health is?”: 1—“Excellent”; 2—“Good”; 3—“Fair”; 4—“Poor”. Self-rated health measures represent relatively stable constructs over repeated observations during adolescence, and when using this measure, reported health deteriorates consistently with a lack of general well-being, disability, healthcare attendance and health-compromising behaviour, attesting to item validity (Idler & Benyamini, 1997).

Demographic covariates

Based upon reported birth month and year and the date of questionnaire administration, the age of each respondent was estimated. Students also reported their gender (boy or girl), and perceived socio-economic status (relative measure of material wealth; how well off to you think your family is? (1—“Very well off”; 2—“Quite well off”; 3—“Average”; 4—Not very well off”; 5—“Not at all well off”). Schools in each country were also numbered in sequence so the effects of the clustered nature of data collection (students nested within schools then countries) could be taken into account in subsequent analyses.

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were conducted with SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, 2013). Descriptive analyses were used to characterize the samples in each country by age and gender. Composite scores for the perceptions of the importance of spiritual health were estimated for each participant. Responses were divided into three groups with cut-points anchored on the response totals, for example with scores of 8–16 representing “not important” (scores averaging 1–2 in the Likert Scale), 17–31 representing “somewhat important (scores averaging >2 and <4 in the Likert Scale), and 32–40 representing “important” (scores average 4–5 on the Likert scale). Percentages of children reporting the different levels of scoring were then described by age and gender within each country. Tests for statistical significance in the linear trends in these proportions were conducted using the Rao–Scott test that accounted for clustering at the school level (Rao & Scott, 1981). We tested for developmental patterns observed by age within genders, as well as differences in responses between the genders. We also used a multivariable log-binomial regression, which accounted for the nested data structure within each country (children nested within schools) to model the developmental trends per two-year age interval, and also relate the multidimensional spiritual health score with self-perceived general health status. These models mathematically adjusted for expected imbalances in basic socio-demographic factors that also relate to spiritual health (gender, socio-economic status), based upon standard criteria for confounding (Rothman, Greenland, & Lash, 2008).

Results

Table 1 profiles the samples available for study. Some country teams asked the spiritual health items of all HBSC ages, while others limited their questioning to older age groups.

Table 1.

Demographic composition of the 45,967 young people from 6 countries that completed the 2014 HBSC spiritual health module.

| Country |

Age groups covered |

Sample | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | ≥15 | Boys | |

| Canadaa | 1124 | 2047 | 2353 | 2602 | 4068 | 12,194 |

| Czech Republic | 383 | 398 | 781 | |||

| England | 577 | 234 | 469 | 165 | 664 | 2109 |

| Israela | 774 | 560 | 300 | 1634 | ||

| Poland | 599 | 623 | 1212 | 2434 | ||

| Scotlanda | 1800 | 1418 | 3218 | |||

| Total | 22,370 | |||||

| ≤11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | ≥15 | Girls | |

| Canadaa | 1186 | 2260 | 2491 | 2915 | 4182 | 13,033 |

| Czech Republic | 405 | 438 | 843 | |||

| England | 508 | 205 | 542 | 186 | 659 | 2100 |

| Israela | 715 | 491 | 427 | 1633 | ||

| Poland | 678 | 624 | 1446 | 2748 | ||

| Scotlanda | 1798 | 1442 | 3240 | |||

| Total | 23,597 | |||||

Sample sizes for Canada, Israel and Scotland are weighted.

The perceptions of young people in terms of how often they viewed each of the eight spiritual health items as “important” are presented in Table 2. Across the six countries, declines in the median proportions of young people reporting such perceptions of importance were observed as children aged. This pattern was observed consistently in both boys and in girls, but less consistently at the country level (N.B., in 3/6 countries; the Czech Republic, Poland, and Scotland, these and subsequent age-related trends were based upon responses from 13 to 15 year-olds, only). Comparisons across the four domains suggest that “connections with others” and “connections with self” were important to strong majorities of young people, irrespective of their age or gender.

Table 2.

Percentages of young people who reported the spiritual health items as important by gender and age group, and number of countries reporting a statistically significant (p<0.05) linear trend in these ratings by age.

| Domain | Item |

Median % by agea |

Number of countries reporting age trendb |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Boys |

Girls |

Boys |

Girls |

||||||||||

| 11 | 13 | 15 | 11 | 13 | 15 | ↓ | = | ↑ | ↓ | = | ↑ | ||

| Others | Be kind to other people | 91 | 84 | 79 | 93 | 90 | 89 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 0 |

| Be forgiving of others | 83 | 75 | 69 | 90 | 80 | 76 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | |

| Self | Feel that your life has meaning or purpose | 85 | 81 | 78 | 88 | 80 | 83 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 0 |

| Experience joy (pleasure, happiness) in life | 90 | 87 | 86 | 91 | 87 | 89 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 0 | |

| Nature | Feel connected to nature | 71 | 60 | 52 | 71 | 65 | 55 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0 |

| Care for the natural environment | 79 | 69 | 56 | 79 | 69 | 63 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0 | |

| Transcendent | Feel a connection to a higher spiritual power | 58 | 41 | 32 | 61 | 43 | 33 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0 |

| Meditate or pray | 45 | 29 | 27 | 48 | 33 | 28 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | |

Average responses, typically estimated within ±4%, were calculated for each county separately and values presented here are the median of those averages.

Each value represents a country.

Similar declines in the perceived importance of the eight spiritual health items were reflected in our multivariable log-binomial regressions, presented here per 2-year age interval (Table 3). The largest declines were observed in the four items describing the last two domains (connections with nature and to the transcendent). There were also some apparent national and perhaps cultural differences in responses observed across the countries under study; for example Israel appeared to be anomalous to the other countries in the last two domains (N.B., this may in part be attributable to its use of only 4 vs. 5 possible response items, which varied from the other 5 countries).

Table 3.

Results of the multivariable log-binomial regression analysis examining relations between age and the rating of spiritual health as important.

| Domain |

England |

Scotland |

Canada |

Czech Republic |

Israel |

Poland |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Age—per 2 yearsa |

Age—per 2 yearsa |

Age—per 2 yearsa |

Age—per 2 yearsa |

Age—per 2 yearsa |

Age—per 2 yearsa |

|||||||

| Item | RR | (95% CI) | RR | (95% CI) | RR | (95% CI) | RR | (95% CI) | RR | (95% CI) | RR | (95% CI) |

| Others | 0.92 | (0.90–0.94) | 0.98 | (0.93–1.03) | 0.98 | (0.96–1.00) | 0.96 | (0.90–1.02) | 0.99 | (0.97–1.02) | 0.98 | (0.96–1.01) |

| Be kind to other people | 0.97 | (0.96–0.98) | 0.99 | (0.95–1.02) | 1.00 | (0.98–1.01) | 0.96 | (0.91–1.01) | 0.99 | (0.98–1.00) | 0.97 | (0.94–0.99) |

| Be forgiving of others | 0.91 | (0.89–0.92) | 0.96 | (0.91–1.02) | 0.97 | (0.95–0.99) | 0.94 | (0.89–0.99) | 0.99 | (0.97–1.02) | 1.00 | (0.97–1.02) |

| Self | 0.96 | (0.94–0.97) | 0.94 | (0.90–0.98) | 0.97 | (0.96–0.99) | 1.01 | (0.97–1.05) | 0.99 | (0.98–1.01) | 1.02 | (0.99–1.04) |

| Life has meaning or purpose | 0.95 | (0.93–0.96) | 0.94 | (0.90–0.98) | 0.97 | (0.96–0.99) | 1.01 | (0.97–1.05) | 1.00 | (0.98–1.02) | 1.01 | (0.98–1.04) |

| Experience joy in life | 0.98 | (0.97–1.00) | 0.96 | (0.93–0.99) | 0.98 | (0.97–0.99) | 1.00 | (0.96–1.03) | 1.00 | (0.99–1.01) | 1.01 | (0.99–1.03) |

| Nature | 0.74 | (0.71–0.77) | 0.76 | (0.69–0.84) | 0.85 | (0.82–0.87) | 0.90 | (0.84–0.98) | 0.95 | (0.89–1.01) | 0.83 | (0.79–0.87) |

| Feel connected to nature | 0.77 | (0.74–0.80) | 0.80 | (0.74–0.87) | 0.88 | (0.85–0.90) | 0.92 | (0.87–0.98) | 1.00 | (0.94–1.06) | 0.86 | (0.82–0.90) |

| Care for natural environment | 0.81 | (0.79–0.83) | 0.82 | (0.77–0.88) | b0.88 | (0.85–0.90) | 0.91 | (0.85–0.98) | 0.94 | (0.90–0.97) | 0.90 | (0.86–0.93) |

| Transcendent | 0.77 | (0.70–0.84) | 1.02 | (0.86–1.23) | 0.81 | (0.77–0.86) | 0.73 | (0.56–0.96) | 1.03 | (0.88–1.22) | 0.85 | (0.79–0.91) |

| Connection to higher power | 0.70 | (0.66–0.74) | 0.82 | (0.73–0.93) | 0.83 | (0.79–0.87) | 0.72 | (0.62–0.85) | 0.98 | (0.87–1.11) | 0.87 | (0.82–0.92) |

| Meditate or pray | 0.84 | (0.77–0.90) | 1.01 | (0.86–1.19) | 0.83 | (0.79–0.88) | 0.78 | (0.60–1.02) | 1.01 | (0.86–1.17) | 0.87 | (0.83–0.92) |

Adjusted for gender and SES (how well off is your family); For England, Scotland, Canada, Czech Republic, and Poland each overall domain important=8–10 (sum of the two domain items), and for each domain item important=4–5; For Israel overall domain important=6–8 and for each domain item important=3–4.

Adjusted only for gender because of model convergence problems (not adjusted for family affluence); all models adjusted for clustering by school and estimates for Scotland, Canada, and Israel have been weighted.

Table 4 summarizes results according to the multidimensional spiritual health score, presented here for exploratory purposes only. These findings demonstrate strong and statistically significant declines in the reported perceptions of spiritual health as being “important” as children aged. Similar to the analyses at the item and domain levels, this pattern was observed consistently by gender within all countries, with the exception of girls from Israel. In addition, in every age group and country, girls scored higher on this composite score than did boys. Percentages of young people within each age/gender grouping reporting the importance of spiritual health to be in the “not important” range were small and these values remained relatively consistent by age group.

Table 4.

Percentage of young people from 6 countries who reported spiritual health as being important by gender and age group.

|

England |

Scotland |

Canada |

Czech Republic |

Israel** |

Poland |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Important | Somewhat | Not | Important | Somewhat | Not | Important | Somewhat | Not | Important | Somewhat | Not | Important | Somewhat | Not | Important | Somewhat | Not | |

| Boys | ||||||||||||||||||

| ≤11 | 60 | 37 | 3 | – | – | – | 63 | 35 | 2 | – | – | – | 76 | 20 | 3 | – | – | – |

| 12 | 51 | 47 | 3 | – | – | – | 57 | 42 | 2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 13 | 36 | 62 | 3 | 30 | 66 | 4 | 51 | 46 | 3 | 41 | 56 | 3 | 69 | 29 | 3 | 51 | 47 | 2 |

| 14 | 35* | 58* | 7 | – | – | – | 43 | 53 | 3 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 44 | 51 | 5 |

| ≥15 | 28 | 68 | 4 | 22 | 73 | 4 | 39 | 57 | 5 | 31 | 66 | 3 | 64 | 32 | 4 | 42 | 54 | 4 |

| Girls | ||||||||||||||||||

| ≤11 | 67 | 30 | 3 | – | – | – | 70 | 28 | 2 | – | – | – | 81 | 18 | 1 | – | – | – |

| 12 | 64 | 34 | 1 | – | – | – | 65 | 34 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 13 | 40 | 56 | 4 | 35 | 63 | 2 | 55 | 43 | 2 | 49 | 48 | 3 | 74 | 25 | 1 | 59 | 40 | 1 |

| 14 | 37 | 60 | 3 | – | – | – | 49 | 48 | 3 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 57 | 40 | 3 |

| ≥15 | 30 | 66 | 4 | 29 | 68 | 4 | 46 | 52 | 2 | 39 | 59 | 2 | 81 | 17 | 2 | 53 | 45 | 2 |

Note: Values are percentages and are typically estimated within ±4%; *estimated ±8%; Spiritual health scores: Important=32–40, Somewhat Important=17 –31, and Not Important=8–16; [**For Israel: Important=24–32; Somewhat important=17–23; and Not Important=8–16]; Proportions for Scotland, Canada, and Israel are weighted.

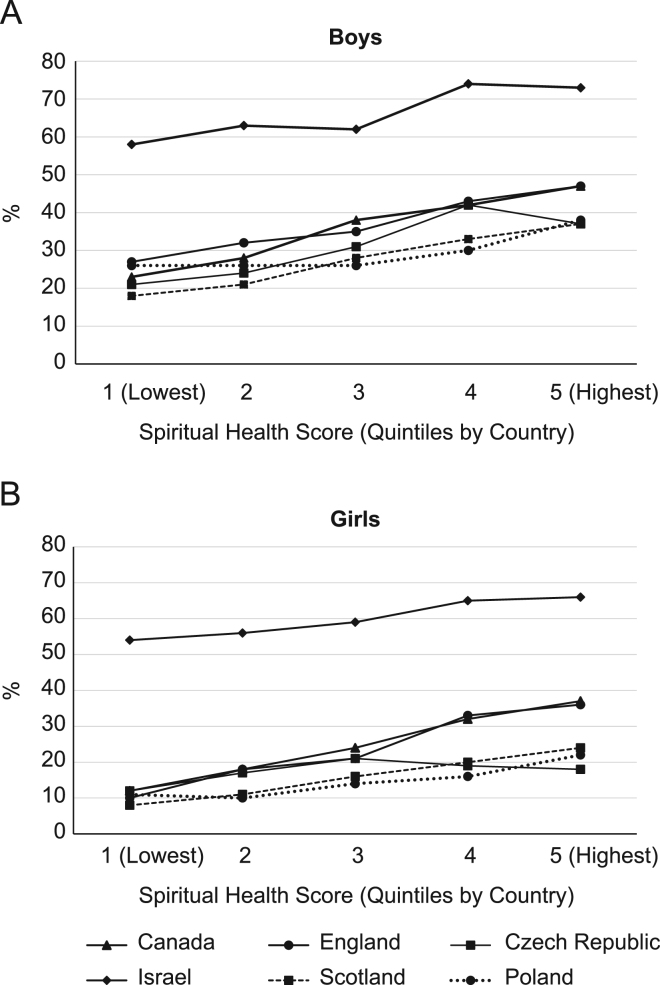

Finally, Fig. 1 shows the proportion of respondents reporting excellent self-perceived health status in relation to their overall multidimensional spiritual health score. Relations were strong and consistent among both boys and girls in each of the six countries. Israel again stood out from all other countries because more young people rated their health as excellent; however, the relationship between the multidimensional spiritual health measure and self-perceived health status was consistent with that observed in other countries.

Fig. 1.

Proportion of boys (panel A) and girls (panel B) reporting excellent health status by overall spiritual health score. All p-trend <0.01, with the exception of Czech Republic Girls (p=0.17). Percentages are estimated within ±5%.

Discussion

This cross-national study examined self-reported perceptions of the importance of spiritual health in the lives of adolescent children in six countries. We explored patterns of children׳s perceptions of the importance of spiritual health, overall and by domain, related to developmental stage, gender, and country. We accomplished this using an abbreviated measure that provides a skeletal view of perceptions of the importance of spiritual health to young people. We also explored relations between the importance of spiritual health measures and self-perceived personal health status. In this discussion, we relate these quantitative findings to existing theories that have been derived in mainly qualitative studies (i.e. Hay & Nye, 1998).

Patterns by age and gender

Age-related declines in the rating of spiritual health as being important were observed consistently across countries and by gender. Several possible explanations exist for these declines. For example, qualitative researchers Hay (anthropology) and Nye (psychology) have argued that an inner sense of spiritual health is innate to the biological make-up of children, and attributed declines in spiritual health to the pervasive influence of society and secular culture (Hay & Nye, 1998). Others explanations for these declines may be related to natural changes in cognition and to the emergence of independent thinking that comes with adolescent growth and development (Piaget, 1972, Butterworth and Harris, 2014, Erikson, 1994). Cognitive changes that emerge with age may enhance children׳s capacities for reason and abstract thought. It is normal for young people to critically reassess concepts as they further become aware of the ideas behind them (Piaget, 1972).

The observed gender-related findings were also striking. Relational aspects of spiritual health were generally rated as being more important among girls than boys, irrespective of the age group or country under study. These findings are consistent with other studies (i.e. Benson, Scales, Syvertsen, & Roehlkepartain, 2012; Hendricks-Ferguson, 2006). Speculatively, this is likely reflective of differences in the ways that girls and boys are nurtured during their early years and socialized as they enter adolescence.

Patterns by domain

Connection with self

While the age-related declines and the gender-related disparities were observed in this domain, the vast majority of young people from all demographic groups still rated the importance of this domain highly. This finding might reflect the values of Euro American societies that see subjective well-being and happiness as individualistic (Luo Lu, 2004). It is also consistent with the idea that personal meaning promotes both wellbeing and happiness in children (Holder et al., 2008). This also connects with a growing body of research that suggests that young people are eager to search for purpose in their lives (Damon, Menon, & Bronk, 2003) and to ask deep questions about ultimate concerns (King & Benson, 2006).

Connection with others

Among girls, this domain was somewhat anomalous to the first domain. While perceptions related to the question about forgiving others followed the typical declining age-related pattern, those related to the item asking about being kind to others did not. Observed gender differences may reflect the ways that girls are nurtured in the early years and then socialized as adolescents. This response profile is positive for the mental health of adolescent girls in that expressions of kindness towards others as well practical acts of volunteering have both been linked to enhanced happiness and well-being (Otake et al., 2006, Post, 2005). Others have shown the positive health benefits of forgiveness, including to one׳s physical, mental and emotional health (Witvliet et al., 2001, Witvliet and McCullough, 2007). The pattern in boys, however, demonstrated a clear decline by age reflected in both questions.

Connection with nature

Findings associated with this domain were unexpected. The consistent decline in this domain observed by age in boys and girls alike contradicts assumptions that young people are likely to be highly engaged with the environment, even though connections with the natural world have long been held to have strong importance to children (Louv, 2005, Louv, 2012). However, such connections may be overestimated for Northern European and North American young people. Explanations for this are complex, but may reflect distinctive changes among the current generation in the nature of childhood and early adolescence, which is known to feature less outdoor play (Gray, 2011) than previous generations. This decline may be related to increased parental concerns around crime and safety as well as to greater time spent interacting with electronic communication technologies (Clements, 2004).

Environmental issues may be regarded with less importance by the groups of young people surveyed when compared with cultures with large populations of Aboriginal persons and adherents to many Eastern religions (Fisher, Francis, & Johnson, 2000). School curricula and social messages often present the environment as being in crisis and in need of human care (i.e. Bigelow & Swineheart, 2014). Rather than experience the “awe and wonder” that might be found in an experience of nature, young people may be more likely to experience the stress connected with environmental degradation (Ojala, 2012, Ojala, 2013).

Connection with the transcendent

The dominant perspective of an increasingly secular west has been challenged by forms of religious resurgence in recent years (Hughes, 2013); however, this does not appear to be central to adolescents in sampled countries (predominantly) from Christian populations. The lower ratings of importance associated with this domain of transcendence were not a surprise as this was the domain that could perhaps be most closely linked to religious experiences. It is also the most mysterious and abstract of the domains. The observed pattern of moving from being “important” to “somewhat important” suggests that children are not rejecting their perceived experience of the importance of spirituality (or potentially in this domain, of religion) completely as they get older. Rather, declines are more likely attributable to external influences and perhaps greater awareness of social expectations, social norms, as well as cultural pressures that may devalue spirituality or religion. And these too follow gender and age-related patterns that are influenced by culture.

Regardless of its origins, a growing body of research demonstrates the deep importance of this transcendent domain, including asking questions about ultimate concerns in life, and expressions of spirituality are not necessarily bound to those experienced in religious environments. Past research suggests that spirituality is connected to happiness in young people (Holder et al., 2008). Further, among those young people who do attend formal religious activities, social self-identification with such communities can be far more important than religious belief as “belonging without necessarily believing” is a typical feature of adolescent religious experiences (Francis & Robbins, 2004). These data do not devalue the positive role that religion can potentially play in facilitating positive spiritual health in young people, and indeed, practices that have arisen from religious traditions also appear to have practical value to health. For example, reflective practices such as prayer (Levin, 1994) and mindfulness-based meditation, which relates both to the domain connection to self and the domain connection to the transcendent, (Biegel, Brown, Shapiro, & Schubert, 2009) relate to many positive health outcomes, such as the alleviation of stress (Grossman, Niemann, Schmidt, & Walach, 2004). The small group of young people that still find this connection to be important may receive health benefits from these priorities.

Israel

Results of the study showed cross-national differences, in particular with some notable differences in Israel, where adolescents reported higher levels for most of the perceptions of spiritual health items (experiencing joy, finding meaning, forgiving others, a connection with a higher spiritual power and meditating/praying). In addition, in comparison to the other countries, levels of the perceived importance of spiritual health did not decline over age and gender differences were less notable. These results are in line with past research with Jewish and Arab adolescents in Israel (Rich & Cinamon, 2007) in which few gender differences were noted and the vast majority of adolescents interviewed discussed a connection to a transcendental being (“something infinitely greater than themselves”). Israel, as a Jewish state with a large Arab minority, is a country in which issues of identity (both religious and secular-ethnic) are paramount. Even among secular Jewish citizens, there is a strong connection to a Jewish identity (CBS, 2009). Higher levels of spirituality among Israeli adolescents may be explained by the importance of ethnic identity (Phinney, 1990) throughout the developmental task of adolescent identity formation in Israel. In addition, definitions of spirituality emphasize a sense of connection to those outside of oneself. Due to its history and current reality, Israel is a country in which many of its citizens feel a strong sense of connection to the state, the community and other Israelis. This feeling that one is part of a greater whole may increase or be part of a sense of spirituality for young Israelis.

Potential influences on adolescent health

Overall, we observed that while the perceived importance of spiritual health declines by age, for adolescents who maintain a strong sense of the importance of self-perceived spiritual health the possible benefits are striking. This was indicated in our findings of self-perceived personal health status, which is a consistent and powerful measure of many aspects of general well-being (Idler & Benyamini, 1997). This relationship was observed consistently across age, gender and countries (see Fig. 1), and while there remains a great deal we do not understand about the etiology or extent of this relationship, the strength and consistency suggests that they merit serious attention. In a companion article, we explore further the relationship between perceived importance of spiritual health and a diversity of physical and emotional health outcomes.

It is perhaps not surprising that the valuing of spiritual health is positive to these health experiences. Past research has focused more specifically on the health-related influences that relate to aspects of the four domains. For example, connection to self (Sinats et al., 2005); connection to peers (Scholte & Van Aken, 2006) and adults (Elgar, Trites, & Boyce, 2010); connection to nature (Louv, 2005, Louv, 2012) and a connection to the realm of transcendence have all been demonstrated to have positive health benefits.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of our study include our embedding of a (necessarily abbreviated) spiritual health measure in a general adolescent health survey, the size and diversity of the study populations and their cross-national nature. While an emerging body of research explores similar themes, including two studies that offer insight on adolescent health and spiritual development in a multi-nation sample that includes developing countries (see Benson et al., 2012; Scales, Syvertsen, Benson, Roehlkepartain, & Sesma, 2014), our study provides a helpful exploration of this topic within our more general health survey context. We therefore feel that it is complimentary to the wider body of research in this field, including the original studies that led to existing theories of the influence of child development on spiritual health (Hay & Nye, 1998). Our findings strongly support the basic tenets of such theories but provide further empirical evidence that demonstrates their universal nature.

Further limitations of our analysis include its cross-sectional design, which makes it difficult to attribute cause and effect. Reverse causality in this situation is unlikely, however, given our focus on demographic factors (age and gender) as the key independent variables. Second, due to the self-reported nature of our study outcomes, it is possible that some misclassification exists in reports of the aspects of spiritual health that we have measured; this misclassification too may vary differentially by age group, gender, and country and bias relationships in unknown directions. Third, our analysis is intentionally descriptive, and we did not make efforts to model and explain the mechanisms behind any observed effects. Age and gender are proxy measures for deeper constructs, with further study warranted to truly understand the developmental and gender-based patterns. Our analysis represents the perceptions of young people from a few countries and such findings may not be generalizable to other contexts and cultures.

One potential criticism of this multidimensional scale that measures perceptions of child spiritual health is that it is operationally very similar to other psychological constructs. The latter include measures of well-being, life satisfaction, and emotional health. These constructs too have some emphasis on connections and relationships, and hence would correlate with this multidimensional measure of adolescent perceptions of spiritual health. Analyses of such correlations may be problematic due to these conceptual overlaps. Further, our measures of perceptions of spiritual health attempt to get at inner experiences and feelings (subjective perceptions of importance) vs. reports of actual spiritual health practices. Such perceptions are clearly not identical to the lived experience of spiritual health. Further study, both qualitative and quantitative, about such lived experiences would be a positive contribution to this area of research.

Finally, the 8-item version of the spiritual health module used admittedly represents only a skeletal view of this construct and its four domains. It was not possible to include the full 20-item Fisher׳s Spiritual Well-being scale for secondary students (Gomez & Fisher, 2003) due to questionnaire response burden in our general health survey context. While extensive efforts were made to validate the abbreviated version and most psychometrics associated with its use were satisfactory, our confirmatory analysis suggests that use of the 8-item version is not optimal, and future work should revert, where possible, to use of the 20-item scale.

Implications

The highly gendered patterns in these self-reported perceptions of the importance of spiritual health, which generally favour girls over boys, suggest that gender-specific curricula and approaches to the promotion of spiritual health may be warranted. In addition, wide variations in the perceived importance of spiritual health exist by domain, and the strong declines observed with age for some key domains suggest a need for a more outward focus to be stressed during adolescence. For example, if spirituality enhances health by increasing personal meaning, strategies aimed at enhancing personal meaning in children׳s lives require promotion. Approaches could include such simple things as encouraging young people to keep journals (Sinats et al., 2005) or to participate in volunteer activities (Post, 2005, Holder et al., 2008). While evidence surrounding their effects is mixed, meditation programs such as mindfulness also appear to be efficacious. Provision of opportunities for young people to not only care for, but also to learn to know and love the natural world, may also be important.

In order for such interventions to be fully informed, there is a need for more in-depth explorations of the mechanisms that lay behind the observed patterns. There is a further need for conceptual work on differences between religiosity and spirituality (as begun by Benson et al. (2012) and Scales et al. (2014)) and a stronger conceptualization of the meaning and assessment of spiritual health in child populations, building on the work of scholars such as Fisher, 1999, Fisher, 2010, Fisher, 2011. More theoretically, questions remain surrounding the societal and personal mechanisms that underlie the decline by age that has been observed in this study, and in particular, if this decline is related to increased exposure to secular aspects of Western culture as children age. Further study of interrelationships between all four domains and whether or not each is equally important to children is also warranted (Fisher, 2011). Finally, efforts are needed to describe spiritual health as a protective asset for specific health outcomes in various contexts and cultures.

Conclusion

Adolescence represents a key time of transition that requires ongoing focus as children learn, grow, and develop cognitively and socially through their formative years. Study findings confirm developmental theories that suggest that the importance of spiritual health, overall and by domain, declines as children grow and develop. Our analysis of the perceptions of young people in 6 countries provides further evidence to this field of study. From the standpoint of health promotion, optimization of spiritual health may be one important way that overall health status can be gained as it may be a positive health asset for young people. There is an inherent elusive quality to spirituality, and so to spiritual health. While we cannot claim to capture the whole of a person׳s spiritual health, this study offers us clues and markers as to how the aspects of “connectedness” among these four domains, which are recognized elements of spiritual health, contribute to the overall health of a child. We reiterate that future work is needed in order to capture a broader picture of spiritual health in adolescent populations, including, where possible, use of Gomez and Fisher׳s full scale (Gomez & Fisher, 2003) versus our 8-item adapted version. Goals of future work could also include moving beyond capturing perceptions of the importance of spiritual health to exploring children׳s lived experiences within each domain. This analysis provides a starting point for etiological research and the development and targeting of health interventions, whether they are in educational, hospital, home or pastoral care settings.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgements

The HBSC is a WHO/Euro collaborative study; International Coordinator of the 2014 study was Candace Currie, St. Andrews University, Scotland; Data Bank Manager is Oddrun Samdal, University of Bergen, Norway. The 6 countries involved in this analysis (current responsible principal investigator) were: Canada (J. Freeman), Czech Republic (M. Kalman), Israel (Y. Harel-Fisch), Poland (J. Mazur), the United Kingdom (England (A. Morgan), Scotland (C. Currie). Funding for this research came from research grants in the following agencies: (1) the Public Health Agency of Canada; (2) the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Operating grant MOP 341188); (3) the Czech Science Foundation (Reg. no. GA14-02804S); (4) the Department of Health for England; (5) the Israeli Ministry of Health; (6) the Institute of Mother and Child in Warsaw, Poland; and (7) NHS Health Scotland.

References

- Benson P.L., Roehlkepartain E.C., Rude S.P. Spiritual development in childhood and adolescence: Toward a field of inquiry. Applied Developmental Science. 2003;7(3):205–213. [Google Scholar]

- Benson P.L., Scales P.C., Syvertsen A.K., Roehlkepartain E.C. Is spiritual development a universal process in the lives of youth? An international exploration. Journal of Positive Psychology. 2012;7(6):453–470. [Google Scholar]

- Bigelow B., Swineheart T. Rethinking Schools; Milwaukee, WI: 2014. A people׳s curriculum for the earth: Teaching climate change and the environmental crisis. [Google Scholar]

- Biegel G.M., Brown K.W., Shapiro S.L., Schubert C. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for the treatment of adolescent psychiatric outpatients: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(5):855–866. doi: 10.1037/a0016241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaney, B., & Smythe, J. Mindfulness training program. 2014, Retrieved from 〈http://meds.queensu.ca/education/postgraduate/wellness/mbsr〉.

- Bone J., Cullen J., Loveridge J. Everyday spirituality: An aspect of the holistic curriculum in action. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood. 2007;8(4):344–354. [Google Scholar]

- Butterworth G., Harris M. Psychology Press; New York: 2014. Principles of developmental psychology. [Google Scholar]

- Caskey, M. M., & Anfara, V. A., Jr. Research summary: Young adolescents’ developmental characteristics. 2007, Retrieved from 〈http://www.nmsa.org/Research/ResearchSummaries/DevelopmentalCharacteristics/tabid/1414/Default.aspx〉.

- CBS . Israel Central Bureau for Statistics; 2009. Social survey 2009—The Jewish population: The place of religion in Israeli public life. [Google Scholar]

- Clements R. An investigation of the status of outdoor play. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood. 2004;5(1):67–80. [Google Scholar]

- Crompton M. Children, spirituality and religion. In: Milnter P., Carolin B., editors. Time to listen to children: Personal and Professional Communication. Routledge; New York, NY: 1999. pp. 79–93. [Google Scholar]

- Currie, C., Zanotti, C., Morgan, A., Currie, D., de Looze, M., Roberts, C., Samdal, O., Smith, O. R. F., & Barnekow, V. Social determinants of health and well-being among young people: Health behaviour in school-aged children (HBSC study): International report from the 2009/2010 survey. Health Policy for Children and Adolescents, Report No. 6, WHO Regional Office for Europe. 2012, Retrieved from 〈http://www.euro.who.int/en/publications/abstracts/social-determinants-of-health-and-well-being-among-young-people.-health-behaviour-in-school-aged-children-hbsc-study〉.

- Damon W., Menon J., Bronk K. The development of purpose during adolescence. Applied Developmental Sciences. 2003;7(3):119–127. [Google Scholar]

- Dhar N., Chaturvedi S., Nandan D. Spiritual health scale 2011: Defining and measuring 4th dimension of health. Indian Journal of Community Medicine. 2011;36(4):275–282. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.91329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhar N., Chaturvedi S., Nandan D. Spiritual health, the fourth dimension: A public health perspective. WHO South-East Asia Journal of Public Health. 2013;2(1):3–5. doi: 10.4103/2224-3151.115826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaude T. National Primary Centre (South West); Bristol: 2003. New perspectives on spiritual development. [Google Scholar]

- Eaude T. Happiness, emotional well-being and mental health: What has children׳s spirituality to offer? International Journal of Children׳s Spirituality. 2009;14(3):185–196. [Google Scholar]

- Elgar F.J., Trites S.J., Boyce W. Social capital reduces socio-economic differences in child health: Evidence from the Canadian health behaviour in school-aged children study. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2010;101(3):S23–S27. doi: 10.1007/BF03403978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson E.H. WW Norton; New York: 1994. Identity: Youth and crisis. [Google Scholar]

- Feudtner C., Haney J., Dimmers M.A. Spiritual care needs of hospitalized children and their families: A national survey of pastoral care providers’ perceptions. Pediatrics. 2003;111(1):e67–e72. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.1.e67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J.W. Developing a spiritual health and life-orientation measure for secondary school students. In: Ryan J., Wittwer V., Baird D., editors. Research with a regional/rural focus: Proceedings of the University of Ballarat inaugural annual conference. University of Ballarat, Research and Graduate Studies Office; Ballarat: 1999. pp. 57–63. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J. Development and application of a spiritual well-being questionnaire called SHALOM. Religions. 2010;1(1):105–121. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J. The four domains model: Connecting spirituality, health and well-being. Religions. 2011;2(1):17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J.W., Francis L.J., Johnson P. Assessing spiritual health via four domains of spiritual wellbeing: The SH4DI. Pastoral Psychology. 2000;49(2):133–145. 37. [Google Scholar]

- Francis L.J., Robbins M. Belonging without believing: A study in the social significance of Anglican identity and implicit religion among 13–15 year-old males. Implicit Religion. 2004;7(1):37–54. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman J.G., King M., Pickett W., Craig W., Elgar F., Janssen I., Klinger D. Public Health Agency of Canada; Ottawa: 2011. The health of Canada׳s young people: A mental health focus; p. 194. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez R., Fisher J.W. Domains of spiritual well-being and development and validation of the spiritual well-being questionnaire. Personality and Individual Differences. 2003;35(8):1975–1991. [Google Scholar]

- Gray P. The decline of play and the rise of psychopathology in children and adolescents. American Journal of Play. 2011;3(4):443–463. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman P., Niemann L., Schmidt S., Walach H. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2004;57(1):35–43. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00573-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay D., Nye R. Fount Paperbacks; London: 1998. The spirit of the child. [Google Scholar]

- Hawks S.R., Hull M.L., Thalman R.L., Richins P.M. Review of spiritual health: Definition, role, and intervention strategies in health promotion. American Journal of Health Promotion. 1995;9(5):371–378. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-9.5.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks-Ferguson V. Relationships of age and gender to hope and spiritual well-being among adolescents with cancer. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 2006;23(4):189–199. doi: 10.1177/1043454206289757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holder M., Coleman B., Wallace J. Spirituality, religiousness, and happiness in children aged 8–12 years. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2008;11(2):131–150. [Google Scholar]

- Houskamp B.M., Fisher L.A., Stuber M.L. Spirituality in children and adolescents: Research findings and implications for clinicians and researchers. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2004;13(1):221–230. doi: 10.1016/s1056-4993(03)00072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, P. A new day for religion in Canada and Australia? Pointers: Bulletin of the Christian Research Association, 23(1), 2013, 5–6. Retrieved from 〈http://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=162333001616314;res=IELHSS〉.

- Hyland M.E., Wheeler P., Kamble S., Masters K.S. A sense of ׳special connection׳, self-transcendent values and a common factor for religious and non-religious spirituality. Archive for the Psychology of Religion—Archiv Fur Religionspsychologie. 2010;32(3):293–326. [Google Scholar]

- Idler E.L., Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven community studies. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1997;38(1):21–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jirásek I. Verticality as non-religious spirituality. Implicit Religion. 2013;16(2):191–201. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman P.I. Humanist spirituality and ecclesial reaction: Thomas More׳s Monstra. Church History. 1987;56(1):25–38. [Google Scholar]

- King P.E., Benson P.L. Spirituality development and adolescent well-being and thriving. In: Roehlkepartain E.C., King P.E., Wagener L., Benson P.L., editors. The handbook of spiritual development in childhood & adolescence. Sage Publications, Inc.; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2006. pp. 384–398. [Google Scholar]

- King P.E., Ramos J., Clardy C. Searching for the sacred: Religion, spirituality, and adolescent development. In: Pargament K.I., Exline J.J., Jones J.W., editors. APA handbook of psychology, religion, and spirituality (Vol. 1): Context, theory, and research. APA; Washington, DC: 2013. pp. 513–528. [Google Scholar]

- Levin J. Is there an association, is it valid, and is it casual? Social Science Medicine. 1994;38(11):1475–1482. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippman L.H., Keith J.D. The demographics of spirituality among youth: International perspectives. In: Roehlkepartain E.C., King P.E., Wagener L., Benson P.L., editors. The handbook of spiritual development in childhood and adolescence. Sage Publications Inc.; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2006. pp. 109–123. [Google Scholar]

- Louv R. Algonquin Books; New York: 2005. Last child in the woods: Saving our children from nature-deficit disorder. [Google Scholar]

- Louv R. Algonquin Books; New York: 2012. The nature principle: Reconnecting with life in a virtual age. [Google Scholar]

- Luo Lu R.G. Culture and conceptions of happiness: Individual oriented and social oriented swb. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2004;5(3):269–291. [Google Scholar]

- Miller J.P., Nakagawa Y., editors. Nurturing our wholeness: Perspectives on spirituality in education. The Foundation for Educational Renewal; Brandon, VT: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Miller W.R., Thoresen C.E. Spirituality, religion, and health: An emerging research field. American Psychologist. 2003;58(1):24–35. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan S. In defence of the indefensible: An alternative to John Paley׳s reductionist, atheistic, psychological alternative to spirituality. Nursing Philosophy. 2009;10(3):203–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-769X.2009.00400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojala M. Regulating worry, promoting hope: How do children, adolescents, and young adults cope with climate change? International Journal of Environmental and Science Education. 2012;7(4):537–561. [Google Scholar]

- Ojala M. Coping with climate change among adolescents: Implications for subjective well-being and environmental engagement. Sustainability. 2013;5(5):2191–2209. [Google Scholar]

- Otake K., Shimai S., Tanaka-Matsumi J. Happy people become happier through kindness: A counting kindness intervention. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2006;7(3):361–375. doi: 10.1007/s10902-005-3650-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer P. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 2009. A hidden wholeness: The journey toward an undivided life. [Google Scholar]

- Pendleton S., Cavalli K., Pargament K., Nasr S. Religious/spiritual coping in childhood cystic fibrosis: A qualitative study. Pediatrics. 2002;109(1):e8. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.1.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney J.S. Ethnic identity in adolescents and adults: review of research. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108(3):499. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piaget J. Intellectual evolution from adolescence to adulthood. Human Development. 1972;15(1):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Post S.G. Altruism, happiness, and health: It׳s good to be good. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;12(2):66–77. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1202_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao J.N.K., Scott A.J. The analysis of categorical data from complex sample surveys: Chi-squared tests for goodness of fit and independence in two-way tables. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1981;76(374):221–230. [Google Scholar]

- Rich Y., Cinamon R.G. Conceptions of spirituality among Israeli Arab and Jewish late adolescents. Journal of Humanistic Psychology. 2007;47(1):7–29. [Google Scholar]

- Roehlkepartain E., King P., Wagener L., Benson P., editors. The handbook of spiritual development in childhood and adolescence. Sage Publications Inc.; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rothman K.J., Greenland S., Lash T.L., editors. Modern epidemiology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sallquist J., Eisenberg N., French D., Purwono U., Suryanti T. Indonesian adolescents’ spiritual and religious experiences and their longitudinal relations with socio-emotional functioning. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46(3):699–716. doi: 10.1037/a0018879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scales P.C., Syvertsen A.K., Benson P.L., Roehlkepartain E.C., Sesma A., Jr. The relation of spiritual development to youth health and well-being: Evidence from a global study. In: Ben-Arieh A., Casas F., Frones I., Korbin J.E., editors. The handbook of child well-being. Springer Netherlands; Dordrecht: 2014. pp. 1101–1135. [Google Scholar]

- Schnell T. Spirituality with and without religion: Differential relationships with personality. Archive for the Psychology of Religion—Archiv Fur Religionspsychologie. 2012;34(1):33–61. [Google Scholar]

- Scholte R.H.J., Van Aken M.A.G. Peer relations in adolescence. In: Jackson S., Goossens L., editors. Handbook of adolescent development. Psychology Press; New York: 2006. pp. 175–199. [Google Scholar]

- Shonin E., Van Gordon W.V., Griffiths M.D. The health benefits of mindfulness-based interventions for children and adolescents. Education and Health. 2012;30(4):95–98. 〈〈http://sheu.org.uk/x/eh304mg.pdf〉〉 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Simkin D.R., Black N.B. Meditation and mindfulness in clinical practice. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics in North America. 2014;23(3):487–534. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinats P., Scott D.G., McFerran S., Hittos M., Cragg C., Brooks D., Leblanc T. Writing ourselves into being: Writing as spiritual self-care for adolescent girls, part 1. International Journal of Children׳s Spirituality. 2005;10(1):17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Smith L., Webber R., DeFrain J. Spiritual well-being and its relationship to resilience in young people. Sage Open. 2013:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson M., Gauntlett-Gilbert J. Mindfulness with children and adolescents: Effective clinical application. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;13(3):395–407. doi: 10.1177/1359104508090603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udermann B.E. The effect of spirituality on health and healing: A critical review for athletic trainers. Journal of Athletic Training. 2000;35(2):194–197. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. Convention on the rights of the child. 1989, Retrieved from 〈http://www.unicef.org/crc/index_protecting.html〉.

- Vader J.P. Spiritual health: The next frontier. European Journal of Public Health. 2006;16(5):457. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckl234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace J. University of British Columbia; BC: 2010. The contributions of spirituality and religious practices to children׳s happiness. [Google Scholar]

- Witvliet C.V.O., Ludwig T.E., Vander Laan K. Granting forgiveness or harboring grudges: Implications for emotion, physiology, and health. Psychological Science. 2001;12:117–123. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witvliet C.V.O., McCullough M.E. Forgiveness and health: A review and theoretical exploration of emotion pathways. In: Post S.G., editor. Altruism and health: Perspectives from empirical research. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2007. pp. 259–276. [Google Scholar]

- Yust K.M., Johnson A.N., Sasso S.E., Roehlkepartain E.C. Traditional wisdom: Creating space for religious reflection on child and adolescent spirituality. Nurturing child and adolescent spirituality: Perspectives from the world׳s religious traditions. 2006:1–14. [Google Scholar]