Abstract

Poor oral health is influenced by a variety of individual and structural factors. It disproportionately impacts socially marginalized people, and has implications for how one is perceived by others. This study assesses the degree to which residents of Canada’s most populated province, Ontario, recognize income-related oral health inequalities and the degree to which Ontarians blame the poor for these differences in health, thus providing an indirect assessment of the potential for prejudicial treatment of the poor for having bad teeth. Data were used from a provincially representative survey conducted in Ontario, Canada in 2010 (n=2006). The survey asked participants questions about fifteen specific conditions (e.g. dental decay, heart disease, cancer) for which inequalities have been described in Ontario, and whether participants agreed or disagreed with various statements asserting blame for differences in health between social groups. Binary logistic regression was used to determine whether assertions of blame for differences in health are related to perceptions of oral health conditions. Oral health conditions are more commonly perceived as a problem of the poor when compared to other diseases and conditions. Among those who recognize that oral conditions more commonly affect the poor, particular socioeconomic and demographic characteristics predict the blaming of the poor for these differences in health, including sex, age, education, income, and political voting intention. Social and economic gradients exist in the recognition of, and blame for, oral health conditions among the poor, suggesting a potential for discrimination amongst socially marginalized groups relative to dental appearance. Expanding and improving programs that are targeted at improving the oral and dental health of the poor may create a context that mitigates discrimination.

Keywords: Ontario, Dentistry, Discrimination, Poverty, Health inequalities, Dental appearance

Highlights

-

•

Poor oral influenced by a variety of individual and structural factors.

-

•

We provide an indirect assessment for prejudicial treatment of the poor for having bad teeth.

-

•

Oral conditions are more commonly perceived as a problem of the poor than are other diseases.

-

•

Socioeconomic gradients predict a potential for discrimination against the poor due to their teeth.

-

•

Our findings support expanding programs to improve the oral health of the poor.

1. Introduction

Income-related health inequalities between the rich and the poor are a well-established phenomenon, in which the poor experience higher rates of heart disease (Bierman, Jaakkimainen & Abramson, 2009), cancer (Krzyzanowska, Barbera & Elit, 2009), lung diseases (Adler, 1993), obesity (Phipps & Lethbridge, 2006), diabetes (Booth, Lipscombe & Bhattacharyya, 2010), and mental health disorders (Government of Canada, 2006). These inequalities also occur for several oral health-related conditions and diseases, as well, such as tooth decay, stained and broken teeth, and missing teeth (Sadeghi, Manson & Quiñonez, 2012). A variety of social and economic factors – commonly referred to as the social determinants of health (SDOH) – have been identified as playing primary roles in establishing and propagating these health inequalities between the rich and the poor. These factors include income inequality, lower levels of education, less job security, poorer employment and working conditions, compromised early childhood development, and inadequate access to housing, among other elements (Mikkonen & Raphael, 2010). In fact, individual oral health behaviours are estimated to explain as little as ten per cent of oral health inequalities between the rich and the poor, with an individual’s socioeconomic status and access to oral health care instead serving as the primary forces driving income-related oral health inequalities (Ramraj, Sadeghi, Lawrence, Dempster & Quiñonez, 2013). To be sure, broad social pressures play a significant role in driving oral health inequalities, which in turn contribute to differences in dental appearance between the rich and the poor.

Importantly, biases towards individuals on the basis of appearance are well-documented. Dion et al., for example, demonstrated that individuals who are physically attractive are immediately attributed other qualities, such as likeability, friendliness, happiness, modesty, intelligence, and general life success (Dion et al., 1972, Montero et al., 2014). More recent studies have also supported these findings in a variety of other settings (Frieze et al., 1991, Mazzella and Feingold, 1994, Khalid and Quiñonez, 2015). Given that North American society associates straight, white teeth with physical attractiveness (Khalid & Quiñonez, 2015), studies have similarly identified biases about personal qualities for those who are perceived by others to have poor oral health on the basis of dental appearance. These biases relate to qualities that include reliability, cleanliness, sociability, intelligence, and better psychosocial stability (Kershaw et al., 2008, Williams et al., 2006, Newton et al., 2003, Duvernay et al., 2014). These prejudices can manifest as discriminatory practices that further complicate individuals’ lives: social exclusion (Eli, Bar-Tat & Kostovetzki, 2001), more difficulty securing employment or living arrangements (Glied and Neidell, 2008, Singhal et al., 2013), and perversely, disinclination by health professionals to provide treatment and even accept these individuals as new patients (Bedos et al., 2013, Bedos et al., 2014, Loignon et al., 2013).

Indeed, recent qualitative studies support the idea that discrimination exists against the poor in Canada for their poor oral health (Bedos et al., 2009, Ravitch and Riggan, 2012, Shankardass et al., 2012, Vallittu et al., 1996). Our study attempts to assess this relationship in Ontario, Canada’s most populated province, by: first, studying the degree to which Ontarians recognize income-related oral health inequalities relative to other general health inequalities; second, examine the degree to which Ontarians blame the poor for these differences in health; and third, identify, amongst those who recognize bad teeth as a condition of the poor, which socioeconomic groups are most likely to blame the poor for these differences in health – and by doing so, provide an indirect assessment of the potential for prejudicial treatment or discrimination of the poor for having bad teeth.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Conceptual Framework

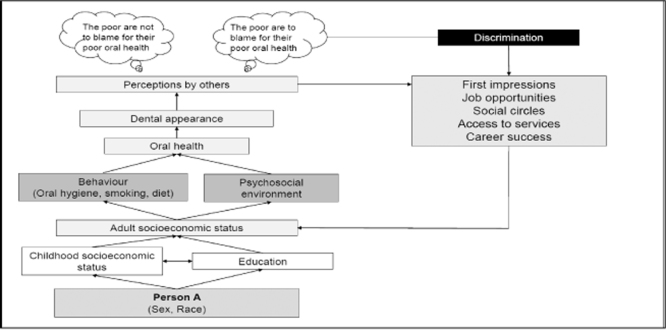

Our conceptual framework uses a working hypothesis model (Ravitch & Riggan, 2012) to approximate peoples’ potential to discriminate against the poor on the basis of dental appearance by linking peoples’ perceptions of the poor having bad teeth, with peoples’ perceptions of why the poor would be in such a position in the first place. If we can show that people readily perceive the poor as having bad teeth (more so than other health conditions), and we can show that certain groups of people attribute blame to the poor for having such conditions, there is an indirect argument to be made in regards to the potential for discrimination. To be sure, if someone is primed to easily recognize bad teeth as a problem of poverty, and if they are also primed to blame the poor for their social situation, there is the potential for prejudicial treatment of the poor for having bad teeth (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Conceptual framework illustrating a pathway in which Person A’s oral health is influenced primarily by factors that are socially and culturally constructed (see Ben-Shlomo and Kuh (2002) for the life-course approach to epidemiology). However, others perceive individual responsibility as the primary force driving poor oral health, and based on perceptions of dental appearance, blames Person A for their deviations from ideal dental health. This discrimination can manifest itself in a variety of outcomes, which in turn, can play an important role in shaping Person A’s socioeconomic status.

2.2. Data Source

The data used for this analysis were gathered in 2010 from 2,006 Ontarians aged 18 years and over through a telephone interview survey using random digit dialing. The market-based research firm contracted to conduct the survey used a random sampling of landline telephone numbers in Ontario, and was required to meet quotas in terms of sex, age, and location. No personal identifiers were collected, surveys were conducted in English, and agreement to participate the survey was taken as consent. The data were weighted to achieve a representative sample of the Ontario population according to 2006 Canadian Census data, in terms of the population’s age, sex, and location. The study was approved by the University of Toronto’s Health Sciences Research Ethics Board (Protocol Reference No. 25583).

2.3. Variables and Data Analysis

This analysis focuses on two broad categories of questions which were asked to participants: (1) awareness of income-related health inequalities; and (2) attributions for the causes of these inequalities. With respect to the first category, participants were asked to agree or disagree with statements suggesting that the rich were less likely than the poor to suffer from fifteen health conditions or diseases for which income-related inequalities have been described (Table 1), including three oral health conditions: tooth decay, stained and broken teeth, and missing teeth. For the second category, participants were presented with two statements framed around blaming the poor for health inequalities (Table 2). For these statements, participants were presented with the response options of strongly agree, agree, disagree, strongly disagree, or neither agree nor disagree. These responses were dichotomized in our analysis to “agree” (strongly agree and agree) and “do not agree” (disagree, strongly disagree, or neither agree nor disagree).

Table 1.

Fifteen health conditions and diseases for which income-related inequalities have been described which were presented to participants to gauge awareness of population-based inequalities between the rich and the poor.

| Health condition or disease | Proportion of respondents that are aware the poor are more likely to suffer from each condition (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Cancer | General health | 10 |

| Diabetes | 25 | |

| Heart disease | 19 | |

| Obesity | 35 | |

| Lung disease | 27 | |

| Mental illness | 22 | |

| Stress and anxiety | 22 | |

| Depression | 23 | |

| Alcoholism | 23 | |

| Dental decay | Oral health | 56 |

| Stained and broken teeth | 58 | |

| Missing teeth | 58 | |

Table 2.

Two statements presented to survey respondents on attributions of income-related health inequalities framed around blaming the poor for their population-level differences in health from the rich, and the social determinant of health to which the statement attributed inequalities.

| Statement | Social determinant of health | Message framing |

|---|---|---|

| The poor are less healthy because of their lifestyles – they smoke and drink more, do not exercise and eat junk food | Health behaviours | Blames the poor |

| The poor spend what money they have unwisely because they do not want to feel excluded from the good things in life | Social exclusion | Blames the poor |

Demographic characteristics were also collected, including: sex (male, female), age (18–34 years, 35–54 years, and 55+ years), location (urban, rural), education level (high school diploma or less, college education, or university degree), visible minority status, political voting intention (which consisted of the three political parties represented in the Ontario legislative assembly in 2010 – Progressive Conservative, Liberal, New Democratic Party (NDP)), and total annual household income (less than $20,000, $20,000–39,999, $40,000–59,999, $60,000–79,999, $80,000–99,999, and more than $100,000).

In order to assess the potential for discrimination against the poor on the basis of their dental appearance, we used a multi-stage process. First, we selected only those participants who demonstrated awareness of oral health inequalities for each of the three conditions described (tooth decay, missing teeth, and stained and broken teeth). Then, we calculated the proportions of these participants who attributed blame to the poor for these differences in health. Finally, we used a binary logistic regression model (controlling for participants’ age and sex) to generate odds-ratios (βx) for all socioeconomic characteristics described above to determine who amongst those who recognize bad teeth as a condition of the poor had greater potential to show biases against the poor for these differences in oral health. All analyses used Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS) Version 22.0 for Windows.

3. Results

The participation rate and demographic profile of participants are described in other publications (Shankardass et al., 2012). Briefly, of 56,528 eligible calls, the survey had a response rate of 5.5% after excluding for numbers that were not in service, fax machines, busy signals, answering machines, no answer, language barriers, and ill or incapable participants. Roughly 52 per cent of participants were female, and 73 per cent of participants reported living in an urban area (geographic area with an urban core of more than 100,000 residents). Roughly 70 per cent of participants reported an annual household income greater than $40,000, and just over 25 per cent of participants had a high school diploma or less as the highest attained education. Almost 40 per cent of participants self-reported having very good or excellent knowledge and understanding of health issues affecting Ontarians.

There was considerably greater recognition for income-related oral health inequalities than for other general health inequalities between the rich and the poor. A majority of participants recognized that the poor suffer disproportionately from all three oral health conditions and diseases presented, including stained and broken teeth (58%), tooth decay (57%), and tooth loss (56%). In comparison, general diseases and conditions – such as cancer (10%), diabetes (25%), heart disease (18%), lung diseases (28%), and obesity (35%) – were far less commonly recognized as conditions of the poor by participants. The proportion of participants who were aware of income-related inequalities was generally consistent for mental health conditions, including mental illness (22%), stress and anxiety (22%), depression (23%), and alcoholism (22%) (Table 1).

Among those who recognize income-related oral health inequalities (roughly 57% of respondents), roughly half (48–50%) attribute these differences in health to be the responsibility of the poor on the basis of what they consider to be poor lifestyle choices – excessive smoking and drinking, poor dietary habits, and lack of physical activity. Roughly one-third of respondents (34%) attribute these differences in health to be the responsibility of the poor due to perceptions of unwise spending decisions on the part of the poor (Table 3).

Table 3.

Proportion of respondents who agreed that (1) the poor are less healthy because of their lifestyles (they smoke and drink more, don’t exercise, and eat junk foods), and (2) the poor spend what money they have unwisely because they do not want to feel excluded from the good things in life, among those respondents who recognize oral health disparities as a condition of the poor among those respondents who recognize each given health condition provided as a condition of the poor.

| Condition X |

Among those who recognize Condition X as a condition of the poor, proportion of respondents that agree: |

|

|---|---|---|

| The poor are less healthy because of their lifestyles – they smoke and drink more, do not exercise and eat junk food | The poor spend what money they have unwisely because they do not want to feel excluded from the good things in life | |

| Cancer | 53% | 38% |

| Diabetes | 56% | 34% |

| Heart Disease | 61% | 39% |

| Obesity | 57% | 38% |

| Lung Disease | 63% | 40% |

| Mental Illness | 57% | 44% |

| Stress & Anxiety | 52% | 39% |

| Depression | 54% | 42% |

| Alcoholism | 61% | 39% |

| Dental Decay | 49% | 33% |

| Stained & Broken Teeth | 48% | 34% |

| Missing Teeth | 50% | 34% |

| ALL RESPONDENTS | 50% | 39% |

Bivariately, amongst those who recognize oral health inequalities between the rich and poor, men were more likely to blame the poor for their perceived lifestyles, as were older respondents (55+ years), and those whose political voting intention was for the Progressive Conservative party. Similarly, socioeconomic differences were found among those who blame the poor for how they spend their money. Again, men, older respondents, and those whose political voting intention was conservative were more likely to hold this perspective, as were those with higher education and those from households earning more income annually. Notably, there appears to be an income gradient, which shows an increasing potential to hold biases against the poor for having bad teeth. The odds are highest for those households with the highest incomes, and as income falls, becomes statistically insignificant (Table 4).

Table 4.

Results of bivariate logistic regression analysis for the odds of agreeing that (1) the poor are less healthy because of their lifestyles (they smoke and drink more, don’t exercise, and eat junk foods), and (2) the poor spend what money they have unwisely because they do not want to feel excluded from the good things in life, among those respondents who recognize oral health disparities as a condition of the poor among those respondents who recognize oral health disparities as a condition of the poor (Agree = 1; Disagree + Neither Agree/Disagree = 0).

| Characteristic |

Adjusted Odds Ratioa(n=895) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The poor are less healthy because of their lifestyles - they smoke and drink more, don’t exercise and eat junk food |

The poor spend what money they have unwisely because they do not want to feel excluded from the good things in life |

||||

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P | ||

| Sex | Male | 1.59 [1.21, 2.08] | 0.001 | 1.55 [1.17, 2.05] | 0.002 |

| Female | Reference | Reference | |||

| Age | 18–34 | 0.46 [0.32, 0.66] | <0.001 | 0.75 [0.52, 1.08] | 0.117 |

| 35–54 | 0.54 [0.40, 0.74] | <0.001 | 0.57 [0.41, 0.78] | 0.001 | |

| 55 and over | Reference | Reference | |||

| Political voting intention | Progressive Conservative | 1.69 [1.04, 2.82] | 0.034 | 1.82 [1.10, 3.01] | 0.020 |

| Liberal Party | 1.24 [0.76, 2.03] | 0.395 | 1.10 [0.66, 1.86] | 0.714 | |

| New Democratic Party | Reference | Reference | |||

| Education attainment | Post-secondary | 1.22 [0.90, 1.65] | 0.210 | 2.06 [1.51, 2.82] | <0.001 |

| High School or less | Reference | Reference | |||

| Residence | Urban | 0.73 [0.54, 1.03] | 0.058 | 1.19 [0.87, 1.62] | 0.280 |

| Rural | Reference | Reference | |||

| Employment status | Employed | 1.49 [0.82, 2.69] | 0.192 | 1.20 [0.65, 2.19] | 0.563 |

| Unemployed | Reference | Reference | |||

| Annual household income | Less than $20,000 | 0.76 [0.46, 1.27] | 0.292 | 0.39 [0.23, 0.67] | 0.001 |

| $20,000–$39,999 | 0.77 [0.49, 1.21] | 0.260 | 0.47 [012, 0.60] | <0.001 | |

| $40,000–$59,999 | 0.61 [0.38, 1.06] | 0.132 | 0.50 [0.30, 0.81] | 0.005 | |

| $60,000–$79,999 | 0.86 [0.53, 1.38] | 0.518 | 0.54 [0.32, 0.90] | 0.018 | |

| $80,000–$99,999 | 0.59 [0.36, 0.97] | 0.036 | 0.61 [0.36, 1.05] | 0.072 | |

| More than $100,000 | Reference | Reference | |||

Model 1: Controlled for the sex and age of respondents.

4. Discussion

In this study, we found that almost 60 per cent of respondents in Ontario, Canada’s most populated province, were aware of three income-related oral health inequalities – tooth decay, missing teeth, and stained and broken teeth. This represents a considerably heightened awareness of health inequalities when contrasted with other general health conditions, such as cancer, diabetes, and depression, for instance.

There are two major explanations for these findings. First, these results are likely a reflection of the highly visible role that teeth play in North American society, and the ease with which ugly teeth and poor oral hygiene are noticed by others (Vallittu et al., 1996). This allows individuals to form broad associations between socioeconomic status and dental appearance through their repeated interactions with those from different social groups. In contrast, other diseases, such as diabetes, cancer, heart disease, mental illness, and depression are considerably less visible to others – sometimes even colloquially referred to as “invisible diseases” (Berne, 2002) – making it much more difficult, though not impossible, for outsiders to establish generalizations between the disease and relevant socioeconomic indicators, such as a person’s education level or family income. As well, this heightened awareness of oral health inequalities may reflect the perception among people in Ontario that dental diseases are simply a condition of the poor, as compared to other systemic illnesses and diseases, which may be perceived to affect anybody, irrespective of economic standing. This may explain, in part, the lower awareness among this sample of Ontarians about other income-related health inequalities.

The second explanation is that differences in the ability to invest in teeth reinforce social class differences (Khalid, 2014), particularly in countries such as Canada, which rely heavily on private insurance and out-of-pocket payments by patients to finance the delivery of dental care services (Ramraj, Weitzner, Figueiredo & Quiñonez, 2014). While Canadians with more precarious employment and a lower socioeconomic status do encounter disproportionate obstacles to receiving care for health conditions generally (Mikkonen & Raphael, 2010), these obstacles are further compounded in a system that places additional cost burdens on patients with limited resources. In this sense, inequalities in oral health can become even more pronounced between the rich and poor.

In addition to indicating socioeconomic characteristics and reinforcing social class differences, teeth can shape how others perceive one’s personality or character. A convincing argument has been proposed that straight, white teeth have developed as a social ideal in North America through the preferences and tastes of the dominant class and market culture (Khalid & Quiñonez, 2015). Those with a dental appearance that does not conform to the ideals put forward by elites are assigned negative personality traits, while those who succeed in attaining this ideal are rewarded for aspiring to the ideals of the dominant class (Khalid & Quiñonez, 2015). Certainly, several studies have identified unconscious biases and perceptions of personal qualities on the basis of failing to conform to these ideal standards (Kershaw et al., 2008, Williams et al., 2006, Newton et al., 2003, Duvernay et al., 2014). Such individuals are perceived to be less reliable, sociable, intelligent, and less psychologically stable.

In this context, it is important that our results found that roughly half of respondents who recognize bad teeth as a condition of the poor attribute these differences in health to problematic lifestyles and/or personal behaviours; respondents blamed the poor for differences in health on the basis of both poor lifestyle choices and judgements about their spending habits. This suggests that there may be heightened potential for discrimination against the poor for health outcomes that are not always wholly individually determined, and that rely heavily on social or economic contexts. These prejudices may be a reflection of a broader acceptance of a more neoliberal philosophy by Ontarians, which considers health to be the responsibility of the individual, and minimizes or dismisses entirely the impact that social factors may play in shaping a person’s health status (Raphael, Curry-Stevens & Bryant, 2008). Despite significant evidence that social factors (largely outside of the control of the individual) are the driving force behind income-related health inequalities (Ramraj et al., 2013), this mantra allows poor oral health to be attributed to individual lifestyle and behavioural factors, like poor dietary habits and poor oral hygiene. This, in turn, encourages the marginalization and stigmatization of those who are unable to conform to the dental norms established by society.

We also found that particular socioeconomic and demographic subgroups in Ontario may have a heightened potential to discriminate against the poor because of bad teeth, including men, older people, those with higher levels of education, and those who identify with conservative politics. Further, an income gradient in this outcome appears to suggest that respondents living in higher income households may be more likely to display discriminatory attitudes towards the poor. These findings may be based upon a lack of lived experience by some respondents, or may be influenced by social norms (Lofters, Slater, Kirst, Shankardass & Quiñonez, 2014).

Our study supports several others in suggesting that the poor face significant social barriers because of bad teeth (Bedos et al., 2009, Hyde et al., 2006, Gift et al., 1992, Hollister and Weintraub, 1993). Therefore, providing dental care to socially marginalized groups can create a context that mitigates things like discrimination. Given this, an expansion of those dental care programs that are targeted at the poor may be warranted – either by extending these programs to more of society’s poorest members (such as the working poor or seniors on fixed incomes), or by increasing the range of benefits that are offered to existing recipients. More importantly, considering that oral health is a product of a wide range of social and economic factors suggests a broader policy approach that focuses on providing solutions that address the social determinants of health.

Our study also highlights the importance of educating the general public on the importance of oral health generally - in terms of both oral health and quality of life, but also with regards to its potential impacts on systemic health conditions. In turn, this might also promote an awareness of its importance, such that people might be less willing or less inclined to discriminate against others with poor oral health. As well, our study demonstrates the importance of educating the public about the social determinants of health; that is, health and disease are often determined by things far beyond individual control, and broader understanding among the general public may mitigate the potential for discrimination.

The study has several limitations, which have been discussed previously (Shankardass et al., 2012), and include: the potential under-sampling of those from lower socioeconomic strata as a result of preferences for cellular telephones over conventional landlines; the absence of respondents who were able to only speak a language other than English; and a low response rate. With that said, given our quota sampling, sample weighting, and annual household incomes and education levels that closely paralleled those observed in the general population, it is arguable that are sample is representative of the Ontario population. Respondents may have also displayed social desirability biases, in which their responses did not reflect their true opinions because they believed that others would unfavourably interpret those responses. Nevertheless, this just means that it is possible that our results underestimate the true degree to which respondents may demonstrate a potential to discriminate against the poor on the basis of dental appearance (Hyde et al., 2006).

Additional limitations exist with respect to particular information that was not collected through the survey. Of note, the survey did not gather data related to participants’ clinical health (dental or systemic), which could shape participants’ responses based on their personal experiences. On the other hand, we did control for the age of respondents in our binary logistic regression model, which may, at least in part, account for respondents’ dental experience. We also explored household income as a variable in the binary logistic regression model, which is the strongest predictor of access to and utilization of dental care services among Canadians (Locker, Maggirias & Quinõnez, 2011). In addition, we had limited information related to the type of dental insurance that individuals had for the purpose of this analysis. Again, however, we may consider household income to serve as an effective proxy for dental insurance, given that there is a strong correlation between a person’s income and their insurance coverage in Ontario (Leake, 2006). Finally, the statements presented to participants framed around blaming the poor for differences in health were not tested for their validity. However, their use has been supported by health inequities literature (Niederdeppe, Bu, Borah, Kindig & Robert, 2008), and has been discussed in previous publications (Shankardass et al., 2012).

5. Conclusion

Social and economic gradients exist for the recognition and blame of oral health conditions among the poor, suggesting the potential for discrimination amongst socially marginalized groups relative to dental appearance. Expanding and improving dental care programs that benefit the poor may create a context that mitigates this state of affairs. Long-term solutions must target programs that are most likely to address the social determinants of health in order to create a more fair and just society.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the funders of this project, the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- Adler N.E. Socioeconomic inequalities in health: No easy solution. Journal of American Medical Association. 1993;269:3140–3145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedos C., Levine A., Brodeur J.M. How people on social assistance perceive, experience, and improve oral health. Journal of Dental Research. 2009;88:653–657. doi: 10.1177/0022034509339300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedos C., Loignon C., Landry A., Allison P.J., Richard L. How health professionals perceive and experience treating people on social assistance: A qualitative study among dentists in Montreal, Canada. BMC Health Service Research. 2013;13:464–473. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedos C., Loignon C., Landry A., Richard L., Allison P.J. Providing care to people on social assistance: How dentists in Montreal, Canada, respond to organisational, biomedical, and financial challenges. BMC Health Service Research. 2014;14:472–479. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shlomo Y., Kuh D. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: Conceptual models, empirical challenges and interdisciplinary perspectives. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;31:285–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berne K.H. Hunter House; Alameda, CA: 2002. Chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia and other invisible illnesses: The comprehensive guide. [Google Scholar]

- Bierman, A.S., Jaakkimainen, R.L., Abramson, B. L., Kapral, M.K., Azad, N., Hall, R., Lindsay, P., Honein, G., & Degani, N. (2009). Cardiovascular disease. In A. S. Bierman (Ed.), The POWER Study Volume 1, Toronto, ON.

- Booth, G.L., Lipscombe, L.L., Bhattacharyya, O., Feig, D.S., Shah, B.R., Johns, A., Degani, N., Ko, B., & Bierman, A.S. (2010). Diabetes. In A. S. Bierman (Ed.), The POWER Study Volume 2, Toronto, ON.

- Dion K., Berscheid E., Walster E. What is beautiful is good. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1972;24:285–290. doi: 10.1037/h0033731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvernay E., Srinivasan M., Legrand L., Herrmann F.R., von Steinbückel N., Müller F. Dental appearance and personality trait judgment of elderly persons. International Journal of Prosthodontics. 2014;27:348–354. doi: 10.11607/ijp.3813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eli L., Bar-Tat Y., Kostovetzki I. At first glance: Social meanings of dental appearance. Journal of Public Health Dentist. 2001;61:150–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2001.tb03382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frieze I.H., Olson J.E., Russell J. Attractiveness and income for men and women in management. Journal of Applied Sociology and Psychology. 1991;21:1039–1057. [Google Scholar]

- Gift H.C., Reisine S.T., Larach D.C. The social impact of dental problems and visits. American Journal of Public Health. 1992;82:1663–1668. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.12.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glied S., Neidell M. The economic value of teeth. NBER Conference Record. 2008:1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada (2006). The human face of mental health and mental illness in Canada, Ottawa, ON.

- Hollister M.C., Weintraub J.A. The association of oral status with systemic health, quality of life, and economic productivity. Journal of Dental Education. 1993;57:901–912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde S., Satariano W.A., Weintraub J.A. Welfare dental intervention improves employment and quality of life. Journal of Dental Research. 2006;85:79–84. doi: 10.1177/154405910608500114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kershaw S., Newton J.T., Williams D.M. The influence of tooth colour on the perceptions of personal characteristics among female dental patients: Comparisons of unmodified, decayed and ׳whitened׳ teeth. British Dental Journal. 2008;204:253–258. doi: 10.1038/bdj.2008.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalid A. University of Toronto; Toronto, ON: 2014. Straight, white teeth as a social prerogative. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalid A., Quiñonez C. Straight, white teeth as a social prerogative. Sociol Health Illinois. 2015;37:782–796. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.12238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krzyzanowska, M.K., Barbera, L., Elit, L., Kwon, J., Lofters, A., Saskin, R., Yeritsyan, N., & Bierman, A.S. (2009). Cancer. In: A. S. Bierman (Ed.) The POWER Study Volume 1, Toronto, ON

- Leake J.L. Why do we need an oral health care policy in Canada? Journal of Canadian Dental Association. 2006;72:317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locker D., Maggirias J., Quinõnez C. Income, dental insurance coverage and financial barriers to dental care among Canadian adults. Journal of Public Health Dentist. 2011;71:327–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2011.00277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lofters A., Slater M., Kirst M., Shankardass K., Quiñonez C. How do people attribute income-related inequalities in health? A cross-sectional study in Ontario, Canada. PLoS One. 2014;9:e85286. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loignon C., Landry A., Allison P.J., Richard L., Bedos C. How health professionals perceive and experience treating people on social assistance: A qualitative study among dentists in Montreal, Canada. Journal of Dental Education. 2013;76:545–562. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzella R., Feingold A. The effects of physical attractiveness, race, socioeconomic status, and gender of defendants and victims on judgments of mock jurors: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1994;42:1315–1338. [Google Scholar]

- Mikkonen J., & Raphael D. (2010). Social Determinants of Health: The Canadian Facts, Toronto, ON, 2010.

- Montero J., Gómez-Polo C., Santos J.A., Portillo M., Lorenzo M.C., Albaladejo A. Contributions of dental colour to the physical attractiveness stereotype. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation. 2014;41:768–782. doi: 10.1111/joor.12194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton J.T., Prabhu N., Robinson P.G. The impact of dental appearance on the appraisal of personal characteristics. International Journal of Prosthodontics. 2003;16:429–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederdeppe J., Bu Q.L., Borah P., Kindig D.A., Robert S.A. Message design strategies to raise public awareness of social determinants of health and population health disparities. Millbank Quarterly. 2008;86:481–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2008.00530.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phipps, S., & Lethbridge, L. (2006). Income and the outcomes of children. In Statistics Canada Analytical Studies Branch Research Paper Series. Ottawa, ON.

- Ramraj C., Weitzner E., Figueiredo R., Quiñonez C. A macroeconomic review of dentistry in Canada in the 2000s. Journal of Canadian Dentist Association. 2014;80:e55-61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramraj C., Sadeghi L., Lawrence H.P., Dempster L., Quiñonez C. Is accessing dental care becoming more difficult? Evidence from Canada׳s middle-income population. PLoS One. 2013;8:E57377. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raphael D., Curry-Stevens A., Bryant T. Barriers to addressing the social determinants of health: Insights from the Canadian experience. Health Policy. 2008;88:222–235. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2008.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravitch S.M., Riggan M. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, PA: 2012. Reason & Rigor: How conceptual frameworks guide research. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi L., Manson H., Quiñonez C. Public Health Ontario; Toronto, ON: 2012. Report on access to dental care and oral health inequalities in Ontario. [Google Scholar]

- Shankardass K., Lofters A., Kirst M., Quiñonez C. Public awareness of income-related inequalities in Ontario, Canada. International Journal of Equity Health. 2012;11:26. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-11-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singhal S., Correa R., Quiñonez C. The impact of dental treatment on employment outcomes: a systematic review. Health Policy. 2013;109:88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallittu P.K., Vallittu A.S.J., Lassila V.P. Dental aesthetics – a survey of attitudes in different groups of patients. Journal of Dental. 1996;24:335–338. doi: 10.1016/0300-5712(95)00079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D.M., Chestnutt I.G., Bennett P.D., Hood K., Lowe R., Heard P. Attitudes to fluorosis and dental caries by a response latency method. Community Dental Oral. 2006;34:153–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2006.00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]