Abstract

Identifying asymptomatic older individuals at elevated risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is of clinical importance. Among 1,081 asymptomatic older adults, a recently validated polygenic hazard score (PHS) significantly predicted time to AD dementia and steeper longitudinal cognitive decline, even after controlling for APOE ε4 carrier status. Older individuals in the highest PHS percentiles showed the highest AD incidence rates. PHS predicted longitudinal clinical decline among older individuals with moderate to high CERAD (amyloid) and Braak (tau) scores at autopsy, even among APOE ε4 non-carriers. Beyond APOE, PHS may help identify asymptomatic individuals at highest risk for developing Alzheimer’s neurodegeneration.

Keywords: polygenic risk, preclinical AD

INTRODUCTION

There is increasing consensus that the pathobiological changes associated with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (AD) begin years if not decades before the onset of dementia symptoms.1,2 Identification of cognitively asymptomatic older adults at elevated risk for AD dementia (i.e. those with preclinical AD) would aid in evaluation of new AD therapies.2 Genetic information, such as presence of the ε4 allele of apolipoprotein E (APOE) can help identify individuals who are at higher risk for AD dementia.3 Longitudinal studies have found that APOE ε4 status predicts decline to mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia4, and steeper cognitive decline in cognitively normal individuals5.

Beyond APOE ε4 carrier status, recent genetic studies have identified numerous single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), each of which is associated with a small increase in AD dementia risk.6 Using genome-wide association (GWAS) from AD cases and controls, we have recently developed a novel ‘polygenic hazard score’ (PHS) for predicting age-specific risk for AD dementia that integrates 31 AD-associated SNPs (in addition to APOE) with US-population based AD dementia incidence rates.7 Among asymptomatic older adults, in retrospective analyses, we have previously shown that the PHS predicted age of AD onset strongly correlates with the actual age of onset.7 To evaluate clinical usefulness and further validate PHS, in this study, we prospectively evaluated whether PHS predicts rate of progression to AD dementia and longitudinal cognitive decline in cognitively asymptomatic older adults and individuals with MCI.

METHODS

We evaluated longitudinal clinical and neuropsychological data (from March 2016) from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC).8 Using the NACC uniform dataset, we focused on older individuals classified at baseline as cognitively normal (CN), with a Clinical Dementia Rating9 (CDR) of 0 and available genetic information (n =1,081, Table 1). We also evaluated older individuals classified at baseline as MCI (CDR = 0.5) with available genetic information (n = 571, Table 1). We focused on CN and MCI individuals with age of AD dementia onset < age 88 to avoid violations of Cox proportional hazards assumption as evaluated using scaled Schoenfeld residuals (total n = 1,652). The institutional review boards of all participating institutions approved the procedures for all ADGC and NIA ADC sub-studies. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants or surrogates.

Table 1.

Cohort demographics

| CN (n = 1,081) | MCI (n = 571) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age ± SD | 71·19 (6·65) | 74·70 (5·85) |

| Education ± SD | 16·07 (2·57) | 15·70 (2·91) |

| Sex (% Female) | 719 (66·51) | 291 (50·96) |

| APOE ε4 carriers (%) | 297 (27·47) | 347 (60·77) |

| Converted to AD dementia (%) | 38 (3·52) | 390 (68·30) |

| Baseline MMSE ± SD | 29·22 (1·05) | 25.67 (3·36) |

MMSE: Mini–Mental State Examination

For each CN and MCI participant in this study, we calculated their individual PHS, as previously described7. In brief, we identified AD associated SNPs (at p < 10−5) using genotype data from 17,008 AD cases and 37,154 controls from Stage 1 of the International Genomics of Alzheimer’s Disease Project. Next, we selected a final total of 31 SNPs based on a stepwise Cox proportional hazards models using genotype data from 6,409 AD patients and 9,386 older controls from Phase 1 of the Alzheimer’s Disease Genetics Consortium (ADGC Phase 1). We corrected the resulting scores for each individual for the baseline allele frequencies using European genotypes from 1000 Genomes Project to derive a PHS for each participant. Finally, by combining US population based incidence rates, and genotype-derived PHS for each individual, we derived estimates of instantaneous risk for developing AD, based on genotype and age. In this study, the PHS computed for every CN and MCI participant represents the vector product of an individual’s genotype for the 31 SNPs and the corresponding parameter estimates from the ADGC Phase 1 Cox proportional hazard model in addition to the APOE effects (for additional details see 7).

We first investigated the effects of the PHS on progression to AD dementia by using a Cox proportional hazards model, with time to event indicated by age of AD dementia onset. We resolved ‘ties’ using the Breslow method. We co-varied for effects of sex, APOE ε4 status (binarized as having at least 1 ε4 allele versus none), education and age at baseline. To prevent violating the proportional hazards assumptions, we additionally included baseline age stratified by quintiles as a covariate.10

Next, we employed a linear mixed-effects (LME) model to evaluate the relationship between PHS and longitudinal clinical decline as assessed by change in CDR-Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB) as well as by change in Logical Memory test (LMT), Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale - Revised (WAIS-R) Digit Symbol, the Boston Naming Test (BNT), Trail-Making Tests A and B (TMTA/B), forward and backward Digit Span (f/b DST) tests. To maintain consistent directionality across all tests, we inverted the scale for Trail-Making tests such that lower scores represent decline. We co-varied for sex, APOE ε4 status, education, baseline age and all their respective interactions with time. We were specifically interested in the PHS × time interaction, whereby a significant interaction indicates differences in rates of decline, as a function of differences in PHS. We then examined the main effect of PHS by comparing slopes of cognitive decline over time in the neuropsychological tests for individuals with high (~84 percentile) and low PHS (~16 percentile), defined by 1 standard deviation above or below the mean of PHS respectively.11 We also compared goodness of fit between the LME models with and without PHS using likelihood ratio tests to determine if PHS LME models resulted in a better fit than non-PHS LME models..

Finally, we evaluated the relationship between PHS, APOE and neuropathology in preclinical AD. Specifically, we conducted LME analysis assessing longitudinal change in CDR-SB in CN individuals with available neuropathology (specifically, neuritic plaque scores based on the Consortium to Establish a Registry for AD (CERAD) and neurofibrillary tangle scores assessed with Braak stages).

RESULTS

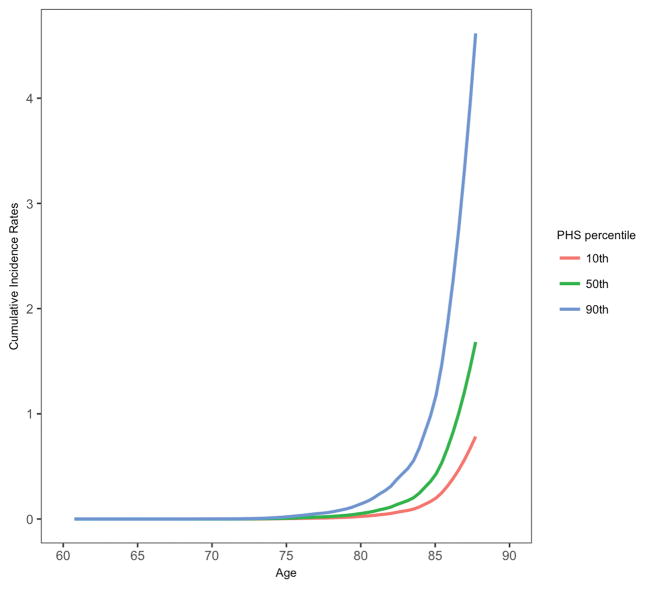

PHS significantly predicted risk of progression from CN to AD dementia (hazard ratio (HR) = 2.36, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.38 – 4.03, p = 1.66×10−3) illustrating that polygenic information beyond APOE ε4 can identify asymptomatic older individuals at greatest risk for developing AD dementia. Individuals in the highest PHS decile had the highest annualized AD incidence rates (Figure 1). PHS also significantly influenced risk of progression to AD dementia in MCI individuals (HR = 1.17, 95% CI = 1.02 – 1.35, p = 2.36×10−2). Using the combined CN and MCI cohorts (total n = 1,652) to maximize statistical power, we found that PHS significantly predicted risk of progression from CN and MCI to AD dementia (HR = 1.31, 95% CI = 1.14 – 1.51, p = 1.82×10−4). At 50% risk for progressing to AD dementia, the expected age for developing AD dementia is approximately 85 years for an individual with low PHS (~16 percentile); however, for an individual with high PHS (~84 percentile), the expected age of onset is approximately 78 years. In all Cox models, the proportional hazard assumption was valid for all covariates.

Figure 1.

Annualized or cumulative incidence rates in CN individuals showing the instantaneous hazard as a function of PHS percentiles and age.

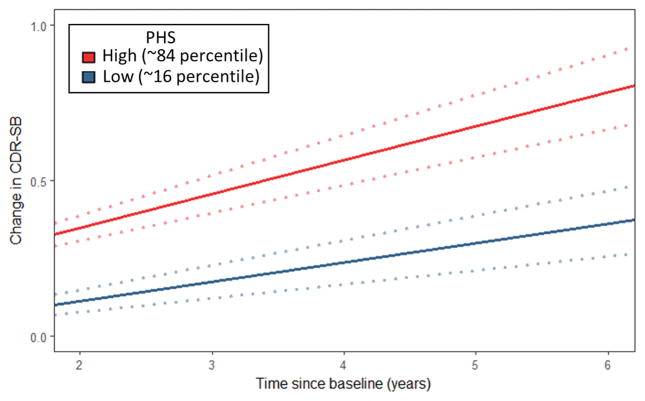

Evaluating clinical progression and cognitive decline within the CN individuals, we found significant PHS by time interactions for CDR-SB (β = 0.05, standard error (SE) = 0.02, p = 3.64×10−4), WAIS-R (β = −0.61, SE = 0.30, p = 4.25×10−2), TMTB (β = −2.48, SE = 0.99, p = 1.20×10−2), and fDST test (β = −0.93, SE = 0.45, p = 3.76×10−2) (Supplemental Table 1), with significantly steeper slopes for high PHS individuals for WAIS-R, TMTB, and CDR-SB (Supplemental Table 2, Figure 2). Evaluating average percentage change across all neuropsychological tests, we found that PHS predicted cognitive decline (β = 0.84, SE = 0.30, p = 4.50×10−3), with high PHS individuals showing greater rates of decline (β = −1.80, SE = 0.89, p = 4.30×10−2) compared to low PHS individuals (β = −0.12, SE = 0.80, p = 0.88). Goodness of fit comparison using likelihood ratio tests showed that the full LME model comprising PHS and covariates resulted in a better model fit for predicting decline in CDR-SB, BNT, WAIS-R, fDST and TMTB (Supplemental Table 3). We found similar results within the MCI individuals and the combined CN and MCI cohort (Supplemental Tables 1–7) illustrating that polygenic information beyond APOE ε4 can identify asymptomatic and mildly symptomatic individuals at highest risk for clinical and cognitive decline.

Figure 2.

Differences in change over time in CDR-SB in CN individuals over time for low (−1 SD, ~16 percentile) and high (+1 SD, ~84 percentile) polygenic hazard score (PHS) individuals. Dotted lines around fitted line indicate estimated standard error.

Finally, among CN individuals with moderate and frequent CERAD “C” score at autopsy, we found that PHS predicted change in CDR-SB over time (β = 1.25, SE = 0.28, p = 6.63×10−6), with high PHS individuals showing a greater rate of increase (β = 5.62, SE = 0.92, p = 1.23×10−9). In a reduced model without PHS, APOE ε4 status did not predict change in CDR-SB (β = 0.26, SE = 0.50, p = 0.61). Furthermore, even in APOE ε4 non-carriers, PHS predicted change in CDR-SB over time (β = 2.11, SE = 0.38, p = 3.06×10−8), with high PHS individuals showing a greater rate of increase (β = 6.11, SE = 1.08, p = 1.60×10−8). Similarly, among CN individuals with Braak stage III – IV at autopsy, PHS predicted change in CDR-SB over time (β = 0.93, SE = 0.24, p = 1.11×10−4), with high PHS individuals showing a greater rate of increase (β = 3.98, SE = 0.79, p = 4.45×10−7).

DISCUSSION

Here, we show that PHS predicts time to progress to AD dementia and longitudinal cognitive decline in both preclinical AD and MCI. Among CN individuals with moderate to high CERAD and Braak scores at autopsy, we found that PHS predicted longitudinal clinical decline, even among APOE ε4 non-carriers. Beyond APOE, our findings indicate that PHS can be useful to identify asymptomatic older individuals at greatest risk for developing AD neurodegeneration.

These results illustrate the value of leveraging the polygenic architecture of the Alzheimer’s disease process. Building on prior work4,5, our findings indicate that polygenic information may be more informative than APOE for predicting clinical and cognitive progression in preclinical AD. Although prior studies have used polygenic risk scores in preclinical AD,12–14 by focusing on maximizing differences between ‘cases’ and ‘controls’, this approach is clinically suboptimal for assessing an age dependent process like AD dementia where a subset of ‘controls’ will develop dementia over time (see Figure 1). Furthermore, given the bias for selecting diseased cases and normal controls, baseline hazard/risk estimates derived from GWAS samples cannot be applied to older individuals from the general population.15 By employing an age-dependent, survival analysis framework and integrating AD-associated SNPs with established population-based incidence rates16, PHS provides an accurate estimate of age of onset risk in preclinical AD.

In our neuropathology analyses, PHS predicted longitudinal clinical decline in older individuals with moderate to high amyloid or tau pathology indicating that PHS may serve as an enrichment strategy for secondary prevention trials. Congruent with recent findings that the risk of dementia among APOE ε4/4 is lower than previously estimated17, among CNs with moderate to high amyloid load, we found that APOE did not predict clinical decline and PHS predicted change in CDR-SB even among APOE ε4 non-carriers. Our combined findings suggest that beyond APOE, PHS may prove useful both as a risk stratification and enrichment marker to identify asymptomatic individuals most likely to develop Alzheimer’s neurodegeneration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Radiological Society of North America Resident/Fellow Award, American Society of Neuroradiology Foundation AD Imaging Award, NACC Junior Investigator award, Research Council of Norway (213837, 225989, 223273, 237250, European Union Joint Program–Neurodegenerative Disease Research), South East Norway Health Authority (2013- 123), Norwegian Health Association, and Kristian Gerhard Jebsen Foundation. Please see Supplementary Table 8 for National Institute on Aging Genetics of Alzheimer’s Disease Data Storage Site, ADGC, and NACC funding sources. We thank the Shiley-Marcos Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at University of California, San Diego; University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Memory and Aging Center; and UCSF Center for Precision Neuroimaging for continued support.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Study concept and design: CHT BTH WPD KK LKM OAA AMD CCF RSD

Data Acquisition and analysis: CHT JJXT CPH GDS LMB WAK CCF RSD

Drafting the manuscript and figures: CHT CCF RSD

POTENTIAL RELEVANT CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None

References

- 1.Dubois B, Hampel H, Feldman HH, et al. Preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: Definition, natural history, and diagnostic criteria. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(3):292–323. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):280–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bu G. Apolipoprotein E and its receptors in Alzheimer’s disease: pathways, pathogenesis and therapy. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10(5):333–344. doi: 10.1038/nrn2620. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonham LW, Geier EG, Fan CC, et al. Age-dependent effects of APOE ε4 in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2016;3(9):668–677. doi: 10.1002/acn3.333. https://doi.org/10.1002/acn3.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caselli RJ, Reiman EM, Locke DEC, et al. Cognitive domain decline in healthy apolipoprotein E epsilon4 homozygotes before the diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2007;64(9):1306–1311. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.9.1306. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneur.64.9.1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lambert JC, Ibrahim-Verbaas CA, Harold D, et al. Meta-analysis of 74,046 individuals identifies 11 new susceptibility loci for Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1452–1458. doi: 10.1038/ng.2802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Desikan RS, Fan CC, Wang Y, et al. Personalized genetic assessment of age-associated Alzheimer’s disease risk. PLoS Med. 2017;14(3):e1002258. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beekly DL, Ramos EM, Lee WW, et al. The National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) database: the Uniform Data Set. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2007;21(3):249–258. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318142774e. https://doi.org/10.1097/WAD.0b013e318142774e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43(11):2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shepard BE. The cost of checking proportional hazards. Stat Med. 2008;15(8):1248–1260. doi: 10.1002/sim.3020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3. Hillsdale: Erlbaum; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sabuncu MR, Buckner RL, Smoller JW, et al. The association between a polygenic Alzheimer score and cortical thickness in clinically normal subjects. Cereb Cortex. 2012 Nov;22(11):2653–61. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marioni RE, Campbell A, Hagenaars SP, et al. Genetic Stratification to Identify Risk Groups for Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;57(1):275–283. doi: 10.3233/JAD-161070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harrison TM, Mahmood Z, Lau EP, et al. An Alzheimer’s Disease Genetic Risk Score Predicts Longitudinal Thinning of Hippocampal Complex Subregions in Healthy Older Adults. eNeuro. 2016 Jul 15;3(3) doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0098-16.2016. pii: ENEURO.0098-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL. Modern Epidemiology. 3. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brookmeyer R, Gray S, Kawas C. Projections of Alzheimer’s disease in the United States and the public health impact of delaying disease onset. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:1337–42. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.9.1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qian J, Wolters FJ, Beiser A, et al. APOE-related risk of mild cognitive impairment and dementia for prevention trials: An analysis of four cohorts. PLoS Med. 2017 Mar 21;14(3):e1002254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.