Abstract

Rationale:

In previous studies, few cases of cervical myelopathy caused by invaginated anomalous laminae of the axis have been reported, and none of them was combined with occipitalization of the atlas.

Patient concerns:

A 28-year-old male was brought to our hospital with motor and sensory impairments of the extremities after a car accident.

Diagnoses:

MRI showed the spinal cord was markedly compressed at the C2/3 level. Reconstructed CT scans revealed an invaginated laminae of axis into the spinal canal as well as atlas assimilation.

Interventions:

The patient was successfully managed with surgical treatment by removal of the anomalous osseous structure as well as fixation and fusion.

Outcomes:

The patient had a rapid recovery after the operation. He regained the normal strength of his 4 extremities and the numbness of his extremities disappeared. He returned to his normal work 3 months after the surgery without any symptoms.

Lessons:

Invaginated laminae of axis combined with occipitalization of the atlas is a rare deformity. MRI and reconstructed CT scans are useful for both diagnosing and surgical planning of this case. Surgical removal of the laminae results in a satisfactory outcome. The pathogenesis of this anomaly could be the fusion sequence error of the 4 chondrification centers in the embryological term.

Keywords: anomaly, axis, cervical myelopathy, chondrification center, occipitalization

1. Introduction

Cervical myelopathy is the most commonly acquired cause of spinal cord dysfunction in aged persons.[1] Anomalies of the upper cervical spine are rare reasons for cervical myelopathy, such as occipitalization of the atlas, atlantal anomalies, posterior C2 arch anomalies, and so on.[2] Compared with the malformations of the atlas, however, those of neural arch of the axis are much rarer. Here we present a case of cervical myelopathy caused by an invaginated laminae of axis combined with atlas assimilation.

2. Case report

A 28-year-old male presented with a 1-day history of paroxysmal numbness of all 4 extremities. One day before, the patient fell on the ground after a car accident, and then he found weakness of his upper extremities, especially in the right one.

The physical examination on admission revealed stable vital signs. Both knee and ankle jerks were hyperactive. The Hoffmann and Babinski signs were positive. Slightly decreased muscle strength of the extremities was observed, which was more obvious in the distal muscle. Touch and pain sensations appeared slightly decreased in both hands. The anal sphincter function and perineal sensations were normal.

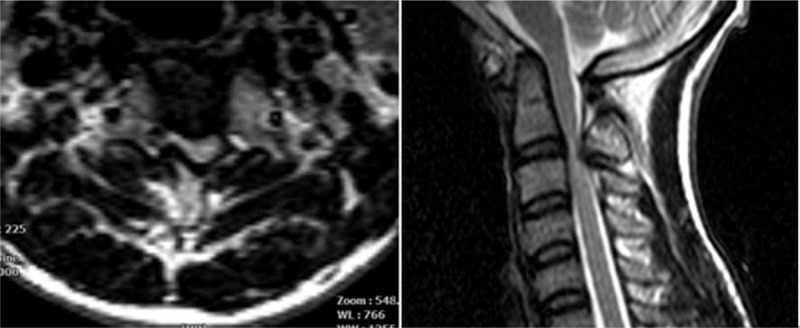

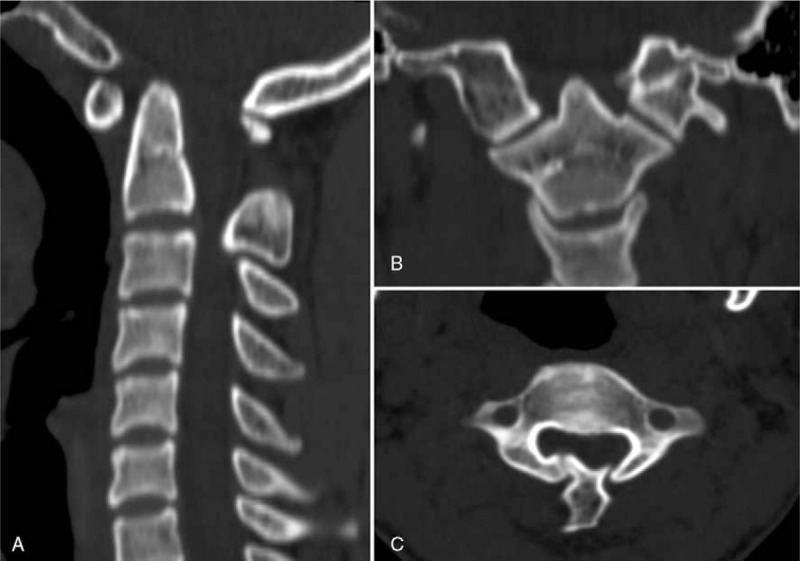

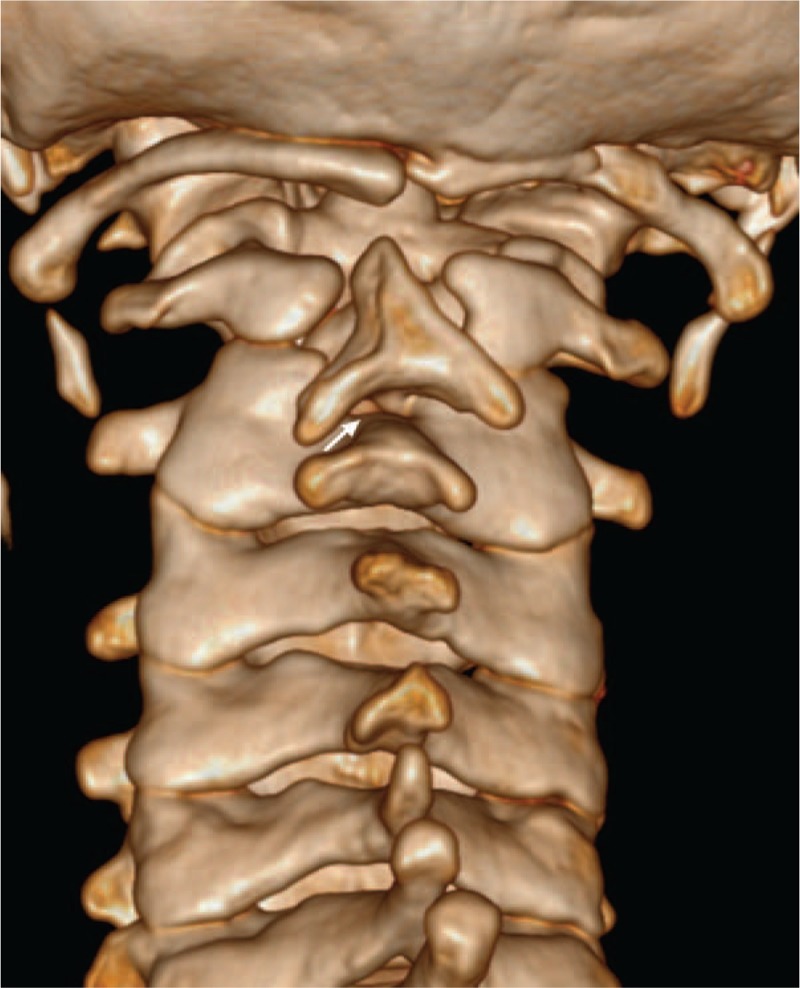

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed the spinal cord with focal hyperintensity in T2-weighted images was markedly compressed by the anomalous osseous structures (Fig. 1). Reconstructed CT scans showed an invaginated laminae into the spinal canal and occipitalization of the atlas (Fig. 2). Moreover, the anomaly of the axis sank into the upper laminae of C3 in which a defect was created (Fig. 3).

Figure 1.

MRI revealed marked spinal cord compression at the level of C2–3 by the anomalous osseous structure. MRI = magnetic resonance imaging.

Figure 2.

The reconstructed sagittal (A), coronal (B), and axial (C) CT scans of the upper cervical unit showed an invaginated laminae and an incomplete occipitalization of the atlas. CT = computed tomography.

Figure 3.

Three-dimensional CT showing this characteristic anomaly directly. A defect (arrow) in the laminae of C3 was created by the anomalous bone. CT = computed tomography.

The patient received a posterior decompressive surgery. Intraoperatively, after releasing the soft tissue that surrounded the invaginated laminae of the axis, we found the anomalous osseous structure was a free fragment (Fig. 4). The invaginated laminae was easily removed. Then the dural membrane retrieved and pulsed well. Finally, C2–3 fixation and fusion with decompressive morselized bone graft was performed (Fig. 5).

Figure 4.

Intraoperative view of the anomalous bony structure revealing a free fragment.

Figure 5.

Postoperative three-dimensional CT image of the patients. A defect in the laminae of C2 and C3 was clearly shown after removal of the anomaly. CT = computed tomography.

Postoperative evaluation showed a rapid recovery. The patient regained the normal strength of his 4 limbs and the numbness of his extremities disappeared. He returned to his normal work 3 months after surgery, free of symptoms. MRI re-examination at 1-year follow-up disclosed decompression at the C2–3 level but showed a persisting intramedullary high signal change (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

MRI scan at the last visit showed the spinal cord was well decompressed but with persisting intramedullary high signal change. MRI = magnetic resonance imaging.

3. Discussion

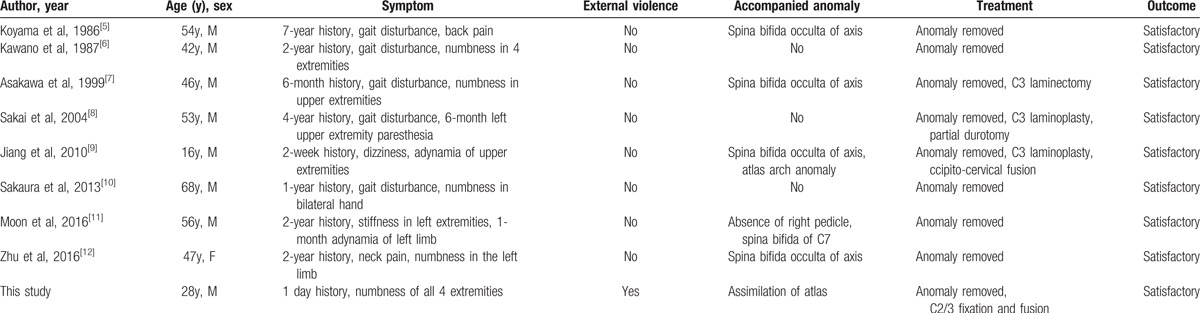

Anomalies of upper cervical spine are by no means rare.[3] Deformities in the region of the axis were categorized by Vangilder et al[3,4] as follows: irregular atlantoaxial segmentation, segmentation failure of C2 and C3, and dens dysplasias. Only 8 cases (Table 1) caused by an invaginated anomalous laminae of the axis have been reported.[5–12] Compared with this type of malformation of axis, the dysplasias of the atlas are much more varied and common, such as occipitalization of the atlas. The incidence of congenital atlanto-occipital fusion ranges from 0.14% to 0.75%.[13] To best of our knowledge, this is the first report in the literature on the cervical deformity of invaginated laminae of axis combined with occipitalization of the atlas.

Table 1.

Summary of cases with cervical myelopathy caused by invaginated laminae of axis.

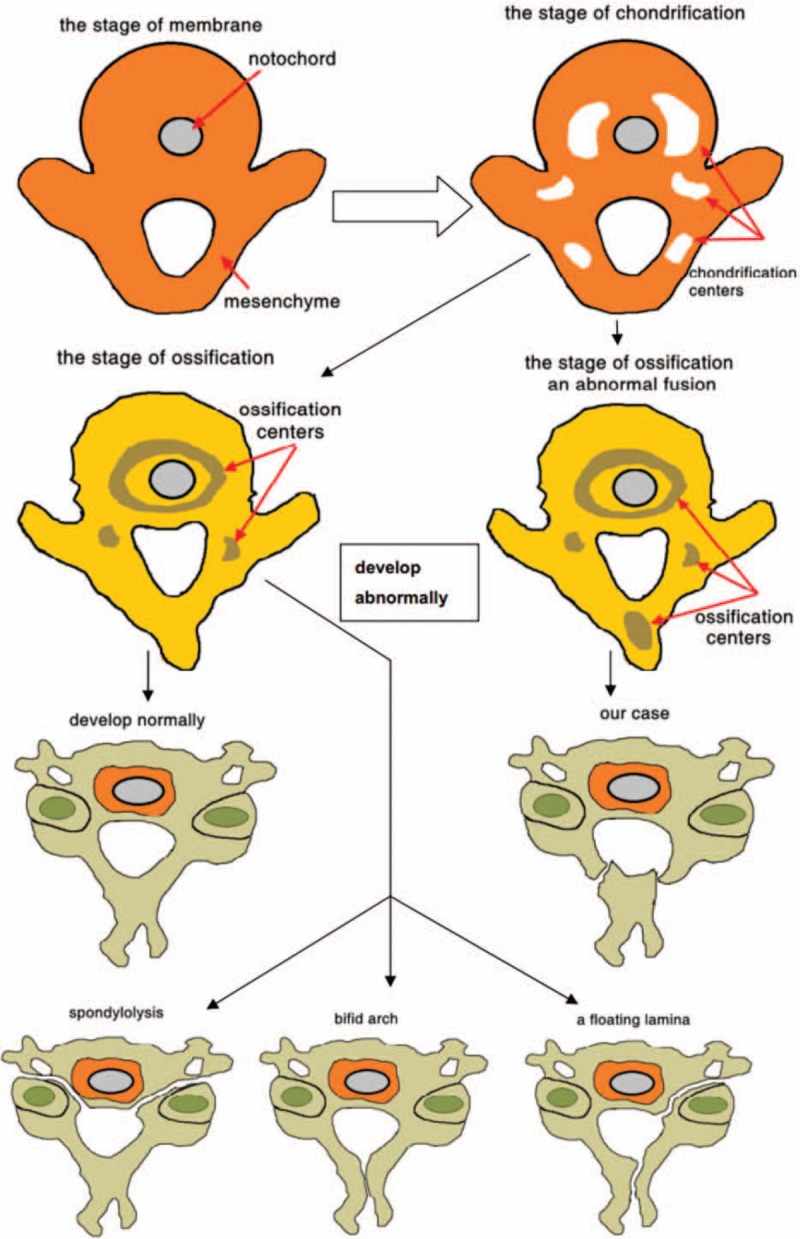

The posterior vertebral arches are formed from 4 chondrification centers at 6 weeks of gestation. At 10 weeks of gestation, 4 chondrification centers unite to form 2 ossification centers on opposite sides of the midline. Each ossification center forms a pedicle, a lateral mass, and half of the laminae. A bifid arch would appear at the age about 2 to 3 years old, when the bilateral ossification centers fails to fuse posteriorly. At about 7-year-old, bilateral ossification centers fuse to the ventral body. Nevertheless, failure of fusion is considered spondylolysis,[9] which has been reported imitating Hangman fracture radiologically.[14–17] The pathogenesis in present case, however, has not been well explained by previous scholars.[5–12] We assume that the 4 posterior chondrification centers fail to fuse into 2 ossification centers bilaterally, but fuse into 3 ossification centers in the early stage. Then each of the 3 ossification centers develops individually instead of fusion to a whole laminae, which leads to the current anomaly (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

A simple simulation process showing the development of a normal and an abnormal axis.

Occipitalization of the atlas is defined as congenital bony fusion of the atlas vertebra to the base of the occipital bone of the skull, which is also known as atlanto-occipital fusion or assimilation of atlas.[18] In the first few weeks of fetal life, the failure of segmentation and separation of the most caudal occipital sclerotome and the first cervical sclerotome will lead to this deformity.[13] It can be divided into complete and partial fusion, ranging from a complete bony fusion to a bony ridge or even a fibrous band uniting a small area of the atlas and occiput.[2] In our case, partial occipitalization of atlas was found through reconstructed CT scans.

In the previous cases, all but 1 case[9] were asymptomatic before the fourth decades (Table 1) and none of them had experienced trauma before they noticed the uncomfortableness. The duration of the symptoms ranged from 2 weeks to 7 years. The chronic myelopathic symptoms might be the natural results in the aging process (such as spondylotic change, ligament hypertrophy, or venous stasis with cord edema), and a patient with congenitally small canal was more likely to experience these symptoms as the age increased. In our case, the 28-year-old man had no symptoms before the accident. He might not realize the malformation without this crash or he would enter the hospital several decades later like the patients mentioned above. In the authors’ opinion, the laminae invaginating into the spinal canal might be the results of both physiological and external force. On one hand, the fibrous band around the free fragment had a traction effect, under which the residual osteophyte became hyperostotic and invaginated into the spinal canal. This mechanism has been well described in some types of aplasia of the posterior arch of C1.[9] The paravertebral muscle was another significant factor which attached to the spinous process of the axis and pulled the laminae caudally. On the other hand, direct external violence, which acted on the mobile laminae would cause acute cervical myelopathy. It was supposed that the cause of some cases manifested clinically late was the relative wider spinal canal at the level of C2.[9] Furthermore, in our case we found the free laminae had partial fibrous connection with the laminae of C3 and then the capacity of the spinal canal could be retained in the early stage. An interesting finding was that only 1 of the patients was female, therefore we guessed that men were more likely to get this anomaly.

All the 9 patients received decompressive surgery by removal of the anomalous bony structure with a favorable outcome.[5–12] Whether to choose an internal fixation/fusion depended on segmental stability, age, patient's expectation, and so on. We fused C2 and C3 instead of fusion to C1 or C0. Therefore, there is potential atlanto-axial instability in the long term. Our patient was very young and had congenitial atlanto-occipital fusion. Excessive fusion could lead to inflexible neck. After informed content, C2/3 fixation and fusion was performed and the term ligament was carefully repaired after resection of the anomalous bone.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CT = computed tomography, MRI = magnetic resonance imaging.

None of the authors received financial support for this study.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].Baptiste DC, Fehlings MG. Pathophysiology of cervical myelopathy. Spine J 2006;6(6 suppl):190–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Klimo PJJr, Rao G, Brockmeyer D. Congenital anomalies of the cervical spine. Neurosurg Clin N Am 2007;18:463–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Vangilder JC, Menezes AH. Craniovertebral junction abnormalities. Clin Neurosurg 1983;30:514–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Vangilder JC, Menezes AH. Wilkins RH, Rengachary SS. Craniovertebral junction anomalies. Neurosurgery. New York, NY: McGrawHill; 1996. 3587–91. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Koyama T, Tanaka K, Handa J. A rare anomaly of the axis: report of a case with shaded three-dimensional computed tomographic display. Surg Neurol 1986;25:491–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kawano K, Uehara S, Nagata Y. A case of myelopathy due to a peculiar anomaly of the axis. Neurol Surg 1987;15:543–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Asakawa H, Yanaka K, Narushima K, et al. Anomaly of the axis causing cervical myelopathy. Case report. J Neurosurg 1999;91(1 suppl):121–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sakai S, Sakane M, Harada S, et al. A cervical myelopathy due to invaginated laminae of the axis into the spinal canal. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2004;29:E82–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Jiang Y, Xi Y, Ye X, et al. A cervical myelopathy caused by invaginated anomaly of laminae of the axis in spina bifida occulta with hypoplasia of the atlas: case report. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010;35:E351–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Sakaura H, Yasui Y, Miwa T, et al. Cervical myelopathy caused by invagination of anomalous lamina of the axis. J Neurosurg Spine 2013;19:694–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Moon BJ, Choi KY, Lee JK. Cervical myelopathy caused by bilateral laminar cleft of the axis: case report and review of literature. World Neurosurg 2016;93:487–1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Zhu C, Zhou B, Liu L, et al. A rare case of cervical myelopathy caused by invaginated laminae of the axis into the spinal canal. Spine J 2016;16:e599–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Yochum TR, Rowe LJ. Essentials of Skeletal Radiology. 1st ed.Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kubota M, Saeki N, Yamaura A, et al. Congenital spondylolysis of the axis with associated myelopathy. Case report. J Neurosurg 2003;98(1 suppl):84–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Matthews LS, Vetter WL, Tolo VT. Cervical anomaly simulating hangman's fracture in a child. Case report. J Bone Joint surg Am 1982;64:299–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Mondschein J, Karasick D. Spondylolysis of the axis vertebra: a rare anomaly simulating hangman's fracture. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1999;172:556–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Smith JT, Skinner SR, Shonnard NH. Persistent synchondrosis of the second cervical vertebra simulating a hangman's fracture in a child. Report of a case. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1993;75:1228–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].McRae DL, Barnum AS. Occipitalization of the atlas. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med 1953;70:23–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]