Abstract

PURPOSE

In the current payment paradigm, reimbursement is partially based on patient satisfaction scores. We sought to understand the relationship between prescription opioid use and satisfaction with care among adults who have musculoskeletal conditions.

METHODS

We performed a cross-sectional study using nationally representative data from the 2008–2014 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. We assessed whether prescription opioid use is associated with satisfaction with care among US adults who had musculoskeletal conditions. Specifically, using 5 key domains of satisfaction with care, we examined the association between opioid use (overall and according to the number of prescriptions received) and high satisfaction, defined as being in the top quartile of overall satisfaction ratings.

RESULTS

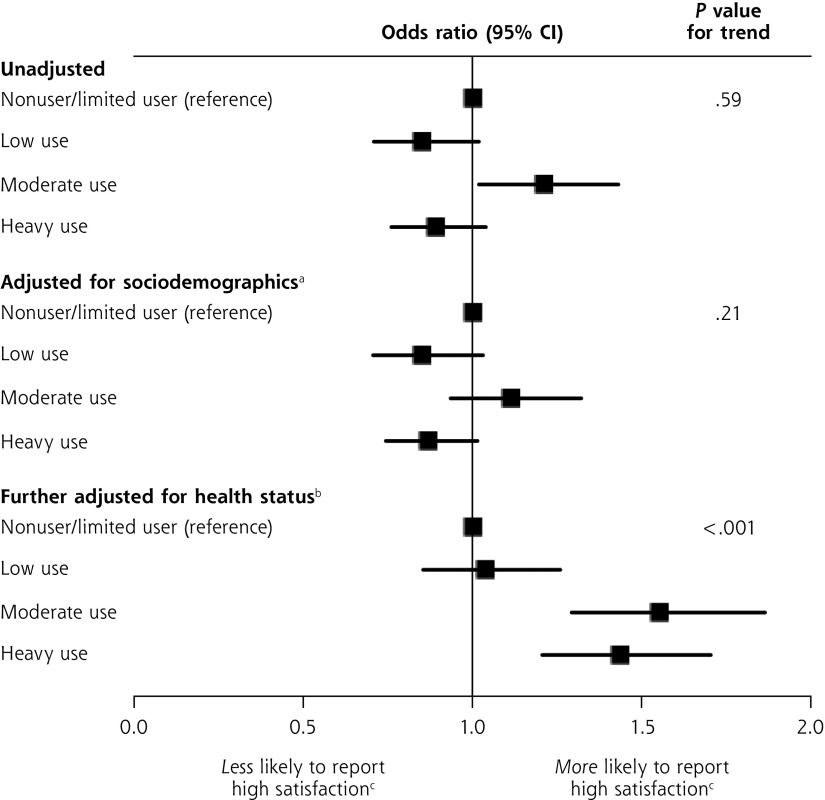

Among 19,566 adults with musculoskeletal conditions, we identified 2,564 (13.1%) who were opioid users, defined as receiving 1 or more prescriptions in 2 six-month time periods. In analyses adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics and health status, compared with nonusers, opioid users were more likely to report high satisfaction with care (odds ratio = 1.32; 95% CI, 1.18–1.49). According to the level of use, a stronger association was noted with moderate opioid use (odds ratio = 1.55) and heavy opioid use (odds ratio = 1.43) (P <.001 for trend).

CONCLUSIONS

Among patients with musculoskeletal conditions, those using prescription opioids are more likely to be highly satisfied with their care. Considering that emerging reimbursement models include patient satisfaction, future work is warranted to better understand this relationship.

Keywords: patient satisfaction, opioids, pain management, musculoskeletal disorders, health care finance, primary care, practice-based research

INTRODUCTION

Providing patient-centered care is at the forefront of American health care reform and is assessed, in part, by patient satisfaction with care.1,2 Results from patient satisfaction surveys have influenced important quality improvement initiatives and, in the current payment paradigm, physicians and hospitals are partially reimbursed based on patient satisfaction scores.3–5 Fenton and colleagues6 found higher patient satisfaction to be associated with greater overall health care use and, surprisingly, increased mortality. Because of concerns about overtreatment and overdiagnosis, considerable controversy has emerged around how efforts to improve patient satisfaction might affect care. Incentives that encourage maximizing patient satisfaction could lead to unforeseen consequences.7

Against the backdrop of excessive health care use, the United States is facing a crisis of prescription opioid drug misuse and diversion resulting in epidemic levels of morbidity and mortality.7,8 According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, use of prescription opioids has quadrupled since 1999; however, the amount of self-reported pain in America has remained unchanged.9 The National Academy of Medicine10 estimates there are nearly 112.5 million US adults who live with pain. Americans therefore regularly interact with their health care professionals seeking pain management expertise. There is growing concern that the combination of patient expectations and satisfaction-linked compensation models may influence physician opioid-prescribing behaviors.7

The extent to which prescription opioid use is associated with patient satisfaction is currently unknown. The rise in the prescription of opioids was presumably initially driven by a desire to improve the well-being of patients having pain. If, in fact, prescription opioid use is associated with higher patient satisfaction with care, such payment incentives may be perpetuating the prescribing of these medications. Alternatively, if prescription opioid use is not associated with patient satisfaction, these medications may have less of an effect than anticipated. It is important for policymakers, clinicians, and other stakeholders to have an accurate understanding of the potential drivers of prescribing in order to develop strategies designed to mitigate the serious public health risks. We therefore analyzed data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) to evaluate whether prescription opioid use is associated with higher levels of patient satisfaction among a large sample of US adults having musculoskeletal conditions.

METHODS

This study used only deidentified and publicly available data; thus, it was deemed exempt from institutional board review by the Dartmouth College Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects (institutional board review no. 00029614; June 13, 2016).

We performed a cross-sectional study to examine the relationship between prescription opioid use and satisfaction with care among adults with musculoskeletal conditions using data from the MEPS. The MEPS is a nationally representative health survey of the non-institutionalized US population conducted annually by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. It is a well-known source of national data on health service use, prescription medications, and health care expenditures that contains both household and insurance components.11,12 The MEPS uses the previous year’s National Health Interview Survey as a sampling frame and applies an overlapping panel design involving 5 rounds of interviews over a 30-month period. Telephone interviews and record abstractions from health care professionals, hospitals, and home health caregivers as well as from pharmacies provide further use and expenditure data. The MEPS Household Component distributes questionnaires to individual household members and collects data on sociodemographic characteristics, health conditions, health status, use of health care services, expenditures on health services, access to care, satisfaction with care, and health insurance coverage.11–13

Each MEPS participant is surveyed every 6 months for 2 years; therefore, the MEPS can be used in both cross-sectional and longitudinal fashion. We used the MEPS longitudinal data to identify a cohort of patients with musculoskeletal conditions and, among these individuals, identified those who used prescription opioids.

Study Population

We used longitudinal data for the years 2008 through 2014 from all study participants in the MEPS Household Component surveys who were aged 18 years and older and had musculoskeletal conditions. These survey years were chosen because they were the most recently available (at the time of analysis).

We identified musculoskeletal conditions using a combination of International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes and patient self-reported data. Specifically, we defined individuals as having a chronic musculoskeletal condition if they had a self-reported diagnosis of chronic joint pain or arthritis, or they had a specific ICD-9-CM code matching a musculoskeletal condition (Supplemental Table 1, available at http://www.annfammed.org/content/16/1/6/suppl/DC1/). The Household Component survey asks participants to disclose health problems, including physical conditions, accidents, and injuries, as well as mental or emotional health conditions. These self-reported conditions are then mapped to ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes by trained MEPS researchers. The specific ICD-9-CM codes used to define chronic musculoskeletal conditions were drawn from prior research and the National Arthritis Data Task Force.14,15 We chose this list of codes based on the likelihood that they define a relatively homogeneous population with chronic diseases that are associated with pain and disability. The MEPS joint pain question inquired whether the person had experienced pain, swelling, or stiffness around a joint in the last 12 months. We defined chronic joint pain as a response of “yes” to this question for both calendar years. The question for arthritis determined whether the person had received a diagnosis of arthritis during either calendar year. We operationally defined an individual as having a musculoskeletal condition if he or she had either an ICD-9-CM code matching those listed in Supplemental Table 1 or answered “yes” to the MEPS joint pain questions in both MEPS follow-up years. We excluded 4,541 adults who had a cancer diagnosis at any point during the 2 years of follow-up.

For the study period, there were 28,036 respondents with complete data who were aged 18 years and older, had a musculoskeletal condition (based on the aforementioned criteria), and did not have cancer at any point during follow-up. Those with incomplete satisfaction data were excluded; thus, our final analytic sample was 19,566 adults with musculoskeletal conditions. We assumed, based on the scant missing data for various covariates and the validated nature of the MEPS collection process, that missing data were missing completely at random.

Study Measures

Satisfaction With Care

MEPS participants who used health care were asked once each year to report their satisfaction with care using a Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Survey (CAHPS). We focused on patient satisfaction with clinician communication because it strongly correlates with the various CAHPS dimensions and with overall satisfaction.16 The MEPS uses 4 categories of clinician behaviors and communication to measure patient satisfaction with care. Specifically, how often in the past 12 months did the patients’ health care professionals perform the following: (1) listen carefully, (2) explain things in a way that was easy to understand, (3) show respect for what they had to say, and (4) spend enough time with them. Additionally, we extracted a fifth item in which patients rated the care from their health care professional on an ordinal scale of 0 to 10 (from the worst to the best health care possible). Satisfaction with care measures were taken from the second calendar year of the survey (the time at which we identified prescription opioid use).

Prescription Opioid Use

MEPS participants are asked to report all health care use on study enrollment and then thereafter at regular 6-month intervals; thus, the 2 years of follow-up results in 5 “rounds” of data. For all adults who report prescription medication use, pharmacies are contacted to validate and augment medication use data. Trained MEPS coders assign a National Drug Code to prescription medications reported by participants. These codes are then merged to classes of drugs using the Multum Lexicon crosswalk (Cerner Corp). We used the Multum drug classes for “narcotic analgesics” and “narcotic analgesics combinations” to identify prescription opioid medications.

Using the longitudinal data files, we identified prescription opioid use in each (6-month) round of follow-up. To reduce classification of individuals with spurious opioid use as opioid users, we defined an opioid user as a participant who received 1 or more opioid prescriptions in at least 2 of the last 3 survey rounds (MEPS rounds 3, 4, and 5). For example, someone who received a single prescription in round 3 and 1 additional prescription in round 5 would be identified as an opioid user. Any opioid prescribing that occurred in rounds 1 or 2 was considered prior opioid use; we explored prior opioid use as a potential covariate.

To explore a potential dose-response, we collapsed opioid users into 3 clinically relevant levels of use based on the total number of opioid prescriptions: low use (2 to 4 opioid prescriptions), moderate use (5 to 9), and heavy use (10 or more). We compared these 3 categories with respondents who were either opioid non-users or limited users (participants having a maximum of 1 prescription for rounds 3, 4, and 5).

Covariates

We anticipated many other factors would predict satisfaction with care and extracted data on sociodemographic characteristics, health, access to health care, and disability (see Table 1). We extracted data on body mass index and calculated the percent of adults who reported any limitations in physical functioning (eg, walking, climbing stairs, lifting, bending, standing); social functioning; cognitive functioning; and work related to pain. We also calculated the percentage of adults who reported any limitations at all during the entire year. Self-reported general health and mental health status was dichotomized into “good to excellent” vs “fair to poor.” These responses to general health status were distinct from those on the 12-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12) that we also examined (both physical and mental component summary scores). The SF-12 pain question on home and work limitations was dichotomized into “moderate to extremely” vs “a little to not at all.” We also identified adults who had inpatient or outpatient surgery, or both.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Adults With Musculoskeletal Conditions According to Opioid Use Status

| Characteristic | Opioid Nonuser/ Limited Usera (n=16,046) | Opioid Usera (n=2,564) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographics | |||

| Age, mean (SE), y | 53.4 (0.1) | 54.7 (0.1) | <.001 |

| Sex, % | .001 | ||

| Male | 38.6 | 35.3 | |

| Female | 61.4 | 64.7 | |

| Race and ethnicity, % | <.001 | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 67.0 | 65.6 | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 20.2 | 24.7 | |

| Hispanic | 3.4 | 3.2 | |

| Other or multiple races | 9.4 | 6.6 | |

| Marital status, % | <.001 | ||

| Married | 55.5 | 46.3 | |

| Divorced, separated, widowed | 26.1 | 38.3 | |

| Never married | 18.4 | 15.4 | |

| US Census region, % | <.001 | ||

| Northeast | 17.9 | 12.5 | |

| Midwest | 21.2 | 22.4 | |

| South | 36.0 | 43.3 | |

| West | 24.9 | 21.9 | |

| Educational attainment, % | <.001 | ||

| High school graduate or less | 63.6 | 78.3 | |

| College degree | 16.7 | 8.6 | |

| Graduate degree | 10.1 | 3.8 | |

| Other degrees | 9.6 | 9.2 | |

| Health insurance, % | <.001 | ||

| Private | 64.3 | 45.1 | |

| Public | 26.4 | 46.3 | |

| Uninsured | 9.3 | 8.5 | |

| Health status | |||

| Body mass index, mean (SE), kg/m2 | 29.1 (0.1) | 31.3 (0.2) | <.001 |

| SF-12 scores, mean (SE) | |||

| PCS score | 46.0 (0.1) | 33.3 (0.2) | <.001 |

| MCS score | 49.9 (0.1) | 44.4 (0.2) | <.001 |

| “Fair” or “poor” overall health, % | 19.7 | 50.5 | <.001 |

| Higher self-reported-pain levelb | 30.5 | 75.5 | <.001 |

| Health care use | |||

| Prior opioid use,c % | 10.3 | 67.2 | <.001 |

| Has usual source of care,d % | 99.7 | 99.3 | .02 |

| Prior inpatient surgery, % | 7.8 | 22.2 | <.001 |

| Prior outpatient surgery, % | 10.0 | 21.3 | <.001 |

| Annual health care spending, median (IQR), $ | 2,380 (5,273) | 7,414 (14,240) | <.001 |

ED=emergency department; IQR=interquartile range; MCS=mental component summary; PCS = physical component summary; SE = standard error; SF-12 = 12-item Short Form Health Survey.

Note: The χ2 test was used to compare proportions, 2-sample t test to compare means, and Mann-Whitney test to compare medians.

Opioid use defined longitudinally using prescriptions received in survey rounds 3 through 5: users (≥1 prescriptions in at least 2 rounds) or nonusers/limited users (0–1 prescriptions).

Percent answering “Moderately,” “Quite a bit,” or “Extremely.”

Prior opioid use defined as receiving 1 or more prescriptions in rounds 1 or 2.

A usual source of care other than the emergency department.

Propensity Score Matching

For a sensitivity analysis, we used nearest-neighbor propensity score matching to select a sample and balance covariates between the 2 groups. We matched each of the 2,564 opioid users to 1 control opioid nonuser. Our propensity score model included sociodemographic characteristics (age, race, education, marital status, insurance coverage, geographic region), self-rated health status, SF-12 physical and mental component summary scores, and body mass index. Variables for the propensity score model were selected using multivariate regression analysis to predict the probability of being an opioid user. Of the 17,002 participants who met criteria for the nonuser group, 2,564 control individuals whose propensity scores matched participants in the opioid user group most closely were selected for inclusion in the final sample. Propensity score matching was performed in R (R Foundation) using the optmatch package version 0.9–7.

Statistical Analysis

We combined the 5 measures of patient satisfaction with care into a single measure.6 To do so, we created a global composite satisfaction measure by standardizing (to weigh each question equally) and averaging responses to the 5 items (mean, 0; median, 0.37; interquartile range, −0.68 to 0.82). On this composite scale, lower scores represent less satisfaction. We then collapsed scores into quartiles.

We performed descriptive analyses to compare differences between opioid users and nonusers/limited users with regard to sociodemographic characteristics, health care use, health status, and the various patient satisfaction metrics. We used a χ2 test for categorical variables and either a Mann-Whitney test or t test for continuous measures. For all analyses, we set the P value for statistical significance to .05 (2-sided).

Logistic regression analysis was used to examine the relationship between opioid use and high satisfaction with care. We identified participants in the highest quartile of satisfaction scores and used this outcome (ie, being in the highest quartile vs all others) as our primary outcome for our logistic models. The relationship between opioid use and high satisfaction with care was examined overall (ie, opioid user vs nonuser/limited user) and by level of use (nonuser/limited user, low use, moderate use, high use). To control for confounding factors, we examined a broad collection of potential covariates in our statistical models including sociodemographic, health status, and health care use factors (eg, health insurance status, annual health care spending, having a usual source of care, and prior opioid use). We adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, and factors that confounded the relationship between opioid use and high satisfaction with care; an independent variable was considered a confounder and included in the final model if it changed the effect estimate (ie, opioid use status) by more than 10%. Our final model was adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, body mass index, self-reported health status, SF-12 physical and mental component summary scores, and level of pain (SF-12 pain question).

To determine if the definition of non-user (ie, a complete nonuser or a limited user) affected our results in any meaningful way, we performed a sensitivity analysis. In this analysis, we compared results with and without excluding those with any opioid use whatsoever in our nonuser comparison group.

RESULTS

Of the 19,566 adults with musculoskeletal conditions studied, 2,564 (13.1%) were prescription opioid users. Within this group, we categorized 29.2% as low-level users, 28.9% as moderate users, and 41.9% as heavy users. Opioid users were slightly older than nonusers, but there were large differences in health status measures (Table 1). Compared with nonusers, users tended to have poorer physical and mental health. For instance, more than one-half of the opioid users rated their physical health as fair to poor, compared with one-fifth of nonusers (P <.001). Additionally, 75% of opioid users rated their pain as moderate to extreme, compared with only 31% of nonusers (P <.001).

Table 2 shows the unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios for the association between characteristics and high satisfaction with care. Adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics and health status, opioid use was associated with a 32% increase in the likelihood of being highly satisfied with care (ie, having a composite satisfaction score in the highest quartile) (odds ratio [OR] = 1.32; 95% CI, 1.18–1.49). In the unadjusted analysis, poor health status was associated with a reduced likelihood of being highly satisfied; however, this finding, was reversed in the adjusted analysis, with poorer health status conferring an 18% increase in the likelihood of high satisfaction (OR = 1.18; 95% CI, 1.06–1.31).

Table 2.

Odds Ratios for the Association Between Characteristics and High Satisfaction With Care

| Characteristic | Odds Ratio (95% CI) for High Satisfaction With Carea

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjustedb | |

| Opioid use status | ||

| Nonuser/limited user (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| User | 0.97 (0.87–1.07) | 1.32 (1.18–1.49) |

| Sociodemographics | ||

| Age, per year | 1.02 (1.02–1.02) | 1.02 (1.02–1.02) |

| Sex | ||

| Male (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Female | 1.15 (1.05–1.25) | 1.25 (1.16–1.34) |

| Race and ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic white (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 1.08 (1.00–1.18) | 1.01 (0.82–1.25) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 0.92 (0.76–1.12) | 1.10 (0.89–1.38) |

| Other | 0.76 (0.66–0.86) | 0.79 (0.62–1.00) |

| Health status | ||

| Body mass index, per kg/m2 | 1.01 (1.00–1.00) | 1.01 (1.00–1.02) |

| SF-12 scores | ||

| PCS score | 1.01 (1.00–1.01) | 1.02 (1.01–1.03) |

| MCS score | 1.03 (1.03–1.04) | 1.03 (1.03–1.04) |

| Self-reported health status | ||

| Excellent to good (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Fair or poor | 0.81 (0.75–0.88) | 1.18 (1.06–1.31) |

| Self-reported pain | ||

| Little or none (ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Moderate to severe | 0.74 (0.69–0.80) | 0.97 (0.87–1.09) |

MCS=mental component summary; PCS=physical component summary; ref=reference group; SF-12 = 12-item Short Form Health Survey.

High satisfaction was defined as having a composite patient satisfaction score in the highest quartile.

Adjusted for all other factors in table.

When we stratified participants by the level of opioid use, the unadjusted association of use with satisfaction was statistically significant only for moderate use, whereas in the adjusted model, there was a strong association for both moderate and heavy uses (Figure 1). Specifically, after adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics and health status, relative to nonusers/limited users, moderate users were 55% more likely to report satisfaction scores in the highest quartile (OR = 1.55; 95% CI, 1.29–1.86) and heavy users were 43% more likely (OR = 1.43; 95% CI, 1.20–1.70). In this model, low-level use was not a significant predictor. Across the 4 categories of increasing opioid use (none/limited, low, moderate, heavy), each increase in category was associated with a 15.0% increase in the odds of being in the highest quartile of satisfaction scores (P for test of trend <.001).

Figure 1.

Odds ratios for the associations between level of prescription opioid use and high satisfaction with care.

Note: Number of prescriptions received in rounds 3 through 5 was used to define nonuse/limited use (0–1), low use (2–4), moderate use (5–9), and heavy use (≥10).

a Adjusted for age (continuous), sex, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic vs other).

b Further adjusted for body mass index (continuous), 12-item Short Form Health Survey mental and physical component scores (continuous), self-reported health status (fair or poor vs all others), and self-reported pain level (moderate or severe vs all others).

c High satisfaction was defined as having a composite patient satisfaction score in the highest quartile.

In the alternative sensitivity analysis using the more stringent definition of nonusers (no opioid prescriptions at all) as the reference category, the association between opioid use and high satisfaction with care remained unchanged.

Propensity Score Analysis

For our propensity matched analysis, we generated the odds ratios for the association between level of prescription opioid use and high satisfaction with care (Supplemental Table 2, available at http://www.annfammed.org/content/16/1/6/suppl/DC1). The findings were similar to those of the standard regression analysis, albeit attenuated. When level of opioid use was considered, the association between use and high satisfaction was statistically significant only for moderate users; specifically, relative to nonusers and limited users, moderate users were 47% more likely to report satisfaction scores in the highest quartile (OR = 1.47; 95% CI, 1.21–1.79). Low-level and heavy users did not differ significantly from nonusers/limited users in this analysis. Across the 4 categories of increasing opioid use (none/limited, low, moderate, heavy), each increase in category was associated with a 6.0% increase in the odds of having a satisfaction score in the highest quartile (P for trend <.04).

DISCUSSION

After accounting for differences among adults having 1 or more musculoskeletal conditions, we found that prescription opioid use was associated with higher satisfaction with care. Among persistent opioid users, moderate and heavy use were associated with approximately 55% and 43% higher likelihoods, respectively, of being in the highest quartile of satisfaction scores compared with no or limited use. Although evidence-based prescribing guidelines are emerging, a complex interaction of factors related to the patient, clinician, medical facts, and social conditions ultimately results in the decision to prescribe an opioid.17 This decision is made more complicated by a health care reimbursement model that may favor overprescribing to optimize patient satisfaction through such mechanisms as the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems. Our findings do not allow us to determine if overprescribing or unnecessary prescribing of opioids is actually occurring, but highlight the future need to establish whether the greater patient satisfaction is actually associated with better health or less disability. Opportunities to reduce opioid prescribing without compromising quality of care are attractive because prescribed opioids constitute the logistical source of these medications for 70% of opioid abusers.18 Current national and state initiatives are emerging and are specifically designed to decrease opioid prescribing by using patient functional improvement as an outcome endpoint rather than patient-reported measures such as satisfaction.19

For patients with musculoskeletal conditions, the association between opioid use and satisfaction may be the result of several factors. On a very basic level, these patients may have a better perceived control of pain than non-users. Our findings indicate, however, that patients with musculoskeletal conditions taking opioids have more pain and worse health and disability than those taking no or limited amounts of these drugs (Table 1), suggesting that the situation is likely more complex. Additionally, in our regression model, we controlled for pain, thus minimizing the experience of pain as a driver of the satisfaction score. The lack of an association between opioid prescribing and improvements in pain on a population health level has been highlighted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, who report that since 1999, the quantity of prescription opioids sold in the United States has almost quadrupled,9 yet there has not been an overall change in the amount of pain that Americans actually report.20,21

Our finding of a positive correlation between greater opioid prescribing and higher satisfaction was surprising to us. On first pass, one could logically predict that opioids may be associated with reduced satisfaction. Beyond the highly publicized concerns regarding addiction and misuse, a high percentage of patients may experience considerable adverse effects. Tolerance, sedation, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, and respiratory depression are common in patients taking these medications.22 Some develop hyperalgesia, which can, paradoxically, worsen the pain experience.23 Additionally, patients frequently report complex opioid-related health challenges such as sexual dysfunction, psychomotor disturbances, cognitive dysfunction, and concerns about controlling opioid use.24 We hypothesize that perhaps the improved satisfaction from opioids may partially be explained by an analogous situation that has been previously documented with antibiotics prescribed for likely viral upper respiratory infections. Several studies indicate that the clinician’s desire to accommodate patient and parent expectations actually leads to overtreatment and overprescribing of oral antibiotics.25,26 Another possible explanation for our findings is that chronic opioid therapy may improve untreated mood disorders, which are highly prevalent, and the patient may perceive alleviation of these symptoms and report this benefit in the form of greater health care satisfaction.27 Only after accounting for differences in health status did we observe an association between opioid use and high satisfaction with care. In univariate analyses, worse health status and self-reported pain level were associated with greater satisfaction with care. This pattern suggests that these factors must be taken into consideration when examining the complex relationship between opioid use and satisfaction with care to avoid biased estimates of the relationship.

In the sensitivity analysis using propensity score matching, we found that opioid use was associated with high satisfaction with care among moderate users but not among heavy users. Although we cannot determine the reason for this notable difference in satisfaction, a possible explanation is that heavy opioid users may be more likely to have uncontrolled pain or receive inadequate or inappropriate treatment for chronic pain. They may also experience more severe adverse effects from opioid use, including complications such as hyperalgesia and substance dependence. Heavy opioid use may also be associated with fragmented care among patients who seek treatment for uncontrolled pain from a variety of clinicians.

There are several limitations to our study that must be acknowledged. First, MEPS data are generalizable only to noninstitutionalized Americans—trends may differ in other groups, such as the military population. Second, MEPS data are observational and based on self-report, and therefore subject to potential unmeasured confounding. In our analyses, we accounted for a large number of important differences, but may have missed some factors. Third, our data lack specificity regarding opioid dose and duration of treatment. It is therefore possible that the absolute dosage of prescription opioid analgesics may be an important driver (negative or positive) of satisfaction. Finally, the poorer health and disability metrics among opioid users (Table 1) should be interpreted with caution. As our data are cross-sectional in nature, it is conceivable that disability and health metrics would have been worse had opioid analgesics not been prescribed. Future prospective observational studies are required to more rigorously evaluate the complex relationships among opioid use, patient satisfaction, physician behaviors, and health metrics.

In conclusion, our study suggests that patients who use prescription opioids for musculoskeletal conditions have greater satisfaction with their care. Opioid users report worse health and disability metrics when compared with nonusers. Given the opioid-related health crisis in the United States, our data suggest that there is an urgent need to establish, on a population health level, whether the observed greater satisfaction with care is associated with demonstrable health benefits.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: authors report none.

Funding support: The Department of Anesthesiology at Dartmouth Medical School provided protected research time for Brian Sites and Michael Beach to support this project.

Supplementary materials: Available at http://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/16/1/6/suppl/DC1/.

References

- 1.Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Groene O. Patient centredness and quality improvement efforts in hospitals: rationale, measurement, implementation. Int J Qual Health Care. 2011;23(5):531–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chue P. The relationship between patient satisfaction and treatment outcomes in schizophrenia. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20(6)(Suppl): 38–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glickman SW, Boulding W, Manary M, et al. Patient satisfaction and its relationship with clinical quality and inpatient mortality in acute myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3(2): 188–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kupfer JM, Bond EU. Patient satisfaction and patient-centered care: necessary but not equal. JAMA. 2012;308(2):139–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fenton JJ, Jerant AF, Bertakis KD, Franks P. The cost of satisfaction: a national study of patient satisfaction, health care utilization, expenditures, and mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(5):405–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zgierska A, Miller M, Rabago D. Patient satisfaction, prescription drug abuse, and potential unintended consequences. JAMA. 2012; 307(13):1377–1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nelson LS, Perrone J. Curbing the opioid epidemic in the United States: the risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS). JAMA. 2012;308(5):457–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Vital Signs: Overdoses of Prescription Opioid Pain Relievers—United States, 1999–2008. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6043a4.htm?s_cid=mm6043a4_w#fig Published Nov 4, 2011. Accessed May 17, 2016. [PubMed]

- 10.Institute of Medicine. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen SB. Design strategies and innovations in the medical expenditure panel survey. Med Care. 2003;41(7)(Suppl):III5–III12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen JW, Cohen SB, Banthin JS. The medical expenditure panel survey: a national information resource to support healthcare cost research and inform policy and practice. Med Care. 2009;47(7) (Suppl 1):S44–S50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Website. http://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/ Published 2013. Accessed Jun 3, 2016.

- 14.Yelin E, Callahan LF; National Arthritis Data Work Groups. The economic cost and social and psychological impact of musculoskeletal conditions. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38(10):1351–1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yelin E, Herrndorf A, Trupin L, Sonneborn D. A national study of medical care expenditures for musculoskeletal conditions: the impact of health insurance and managed care. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(5):1160–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hargraves JL, Hays RD, Cleary PD. Psychometric properties of the Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Study (CAHPS) 2.0 adult core survey. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(6 Pt 1):1509–1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turk DC, Okifuji A. What factors affect physicians’ decisions to prescribe opioids for chronic noncancer pain patients? Clin J Pain. 1997; 13(4):330–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Volume I. Summary of National Findings. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, SAMHSA, Office of Applied Studies; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agency Medical Directors Group. Interagency Guideline on Prescribing Opioids for Pain. http://www.agencymeddirectors.wa.gov/Files/2015AMDGOpioidGuideline.pdf Published Jun 2015. Accessed Jun 1, 2016.

- 20.Chang HY, Daubresse M, Kruszewski SP, Alexander GC. Prevalence and treatment of pain in EDs in the United States, 2000 to 2010. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32(5):421–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daubresse M, Chang HY, Yu Y, et al. Ambulatory diagnosis and treatment of nonmalignant pain in the United States, 2000–2010. Med Care. 2013;51(10):870–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Labianca R, Sarzi-Puttini P, Zuccaro SM, Cherubino P, Vellucci R, Fornasari D. Adverse effects associated with non-opioid and opioid treatment in patients with chronic pain. Clin Drug Investig. 2012; 32(S1):53–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayhurst CJ, Durieux ME. Differential opioid tolerance and opioid-induced hyperalgesia: a clinical reality. Anesthesiology. 2016;124(2): 483–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sullivan MD, Von Korff M, Banta-Green C, Merrill JO, Saunders K. Problems and concerns of patients receiving chronic opioid therapy for chronic non-cancer pain. Pain. 2010;149(2):345–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Macfarlane J, Holmes W, Macfarlane R, Britten N. Influence of patients’ expectations on antibiotic management of acute lower respiratory tract illness in general practice: questionnaire study. BMJ. 1997;315(7117):1211–1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamm RM, Hicks RJ, Bemben DA. Antibiotics and respiratory infections: are patients more satisfied when expectations are met? J Fam Pract. 1996;43(1):56–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Edlund MJ, Martin BC, Devries A, Fan MY, Braden JB, Sullivan MD. Trends in use of opioids for chronic noncancer pain among individuals with mental health and substance use disorders: the TROUP study. Clin J Pain. 2010;26(1):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]