Summary

Macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) is hyperinflammatory life‐threatening syndrome, associated typically with high levels of serum ferritin. This is an iron storage protein including heavy (H) and light (L) subunits, categorized on their molecular weight. The H‐/L subunits ratio may be different in tissues, depending on the specific tissue and pathophysiological status. In this study, we analysed the bone marrow (BM) biopsies of adult MAS patients to assess the presence of: (i) H‐ferritin and L‐ferritin; (ii) CD68+/H‐ferritin+ and CD68+/L‐ferritin+; and (iii) interleukin (IL)‐1β, tumour necrosis factor (TNF) and interferon (IFN)‐γ. We also explored possible correlations of these results with clinical data. H‐ferritin, IL‐1β, TNF and IFN‐γ were increased significantly in MAS. Furthermore, an increased number of CD68+/H‐ferritin+ cells and an infiltrate of cells co‐expressing H‐ferritin and IL‐12, suggesting an infiltrate of M1 macrophages, were observed. H‐ferritin levels and CD68+/H‐ferritin+ cells were correlated with haematological involvement of the disease, serum ferritin and C‐reactive protein. L‐ferritin and CD68+/L‐ferritin+ cells did not correlate with these parameters. In conclusion, during MAS, H‐ferritin, CD68+/H‐ferritin+ cells and proinflammatory cytokines were increased significantly in the BM inflammatory infiltrate, pointing out a possible vicious pathogenic loop. To date, H‐ferritin and CD68+/H‐ferritin+ were associated significantly with haematological involvement of the disease, suggesting biomarkers assessing severity of clinical picture.

Keywords: cytokine, ferritin, hyperferritinaemic syndrome, macrophage, macrophage activation syndrome

Introduction

Macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) is a hyperinflammatory syndrome, associated usually with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis and adult‐onset Still's disease (AOSD) 1, 2, 3, 4. Due to this close association, it has been suggested that MAS and AOSD may represent one part of the same disease spectrum, of which AOSD may be considered the milder form 5. In this context, it has been shown that MAS occurrence may be misdiagnosed due to immunosuppressive drugs used to treat AOSD flare, thus reducing the reported prevalence of this syndrome 6, 7. Furthermore, patients affected by systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) may also experience MAS 8. Continuous high fever, hepatosplenomegaly, severe peripheral blood cytopenia and haemophagocytosis by activated macrophages in bone marrow (BM) are typical features of these patients 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8. In contrast to paediatric patients, the therapeutic strategies of adults derive mainly from case–series and retrospective experiences 9, 10, 11. In this context, the clearance of possible triggers, immunosuppressive therapeutic strategies and supportive care are considered the main therapeutic strategies 10. Despite aggressive therapeutic strategies, MAS is one of the most critical clinical disorders in adults, evolving to multiple organ failure and unfavourable outcome 1, 8. This result may be possibly related, in adult age, with an increased presence of co‐morbidities, the latter known to be predictive of a more severe outcome in MAS patients as observed in other rheumatic diseases 3, 8, 12.

Recently, a multi‐layer MAS pathogenic model during inflammatory rheumatic diseases has been proposed 2. Genetic factors, proinflammatory milieu associated with the underlying rheumatic disease, trigger factors and the uncontrolled activation of macrophages and T cells may lead to the development of cytokine storm and MAS 13, 14. Activation of cytotoxic CD8 T lymphocytes with production of macrophage‐activating cytokines, such as interferon (IFN)‐γ, is an early event in MAS pathogenesis. Defects in granulocyte‐mediated cytotoxicity, enhanced antigen presentation and repeated stimulation of Toll‐like receptors determine extensive production/release of tumour necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin (IL)‐1β 13, 14. The consequent activation and expansion of monocytes and macrophages lead to pathological haematophagocytosis 1, 2, 13, 14. In this context, it has been considered that macrophages are categorized in M1 (classically activated), releasing proinflammatory mediators, and M2 (alternatively activated), modulating the inflammatory response 15.

During MAS, a possible pathogenic role of ferritin has been suggested and has been included in the so‐called ‘hyperferritinaemic syndrome’ 16, 17. Ferritin is an intracellular iron storage protein including 24 subunits. These are categorized, according to molecular weight, as heavy (H) subunits and light (L) subunits. Ferritin enriched in L subunits (L‐ferritin) has been found in liver and in spleen, whereas ferritin enriched in H subunits (H‐ferritin) may be observed mainly in heart and kidneys 17. Possible causes of hyperferritinaemia in these patients include increased production to sequestrate free iron of released haemoglobin due to erythrophagocytosis, reduced tissue clearance and enhanced production by macrophages 16, 17.

In this study, we aimed to investigate H‐and L‐ferritin in inflammatory BM infiltrate of MAS patients during full‐blown syndrome. Macrophage subsets expressing H‐and L‐ferritin were also assessed. Furthermore, we evaluated IL‐1β, TNF, IFN‐γ and their possible co‐localization with ferritin within inflammatory cells. Finally, any possible clinical correlation of these data with the severity of the disease was analysed.

Patients and methods

A retrospective evaluation of BM biopsies obtained from adult MAS patients admitted to the Rheumatology Clinic of L'Aquila University and Rheumatology Clinic of Palermo University during the last 10 years was performed. MAS patients were diagnosed according to 2004 haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) diagnostic guidelines criteria 18. In this study, we also evaluated 10 biopsies derived from BM‐donors, used as healthy controls (HCs).

For each patient we analysed age, gender, values of white blood cell count (WBC), red blood cells (RBC), haemoglobin (HB), platelet count (PLT), serum ferritin, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C‐reactive protein (CRP), aspartate aminotransferase (ASAT) and alanine aminotransferase (ALAT) during the full‐blown syndrome.

The local ethics committee approved the study (ASL1 Avezzano‐Sulmona‐L'Aquila, L'Aquila, Italy, protocol number 0122353/17) that was performed according to Good Clinical Practice guidelines and Declaration of Helsinki.

Histological analysis of biopsies

Samples were stained with anti‐H‐ferritin, anti‐L‐ferritin, anti‐CD68, anti‐CD163, anti‐IL‐1β, anti‐IL‐12, anti‐IFN‐γ and anti‐TNF antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), as reported previously 16. Samples were acquired using a light microscope (Olympus BX53) and immunofluorescence images by CellSens software (Olympus America Inc., Center Valley, PA, USA). Cells double‐positive for both CD68/H‐ferritin and CD68/L‐ferritin were counted in sections from randomly selected areas of the BM, counting at least 500 nucleated cells (×20 magnification) by using NIHimageJ version 1.43 (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/) freeware.

Statistical analysis

To compare the results of MAS patients and HCs, the Mann–Whitney U‐test was considered appropriate due to the non‐parametric distribution of our data. To assess correlations among tissue H‐ and L‐ferritin, the numbers of double‐positive cells for CD68 and H‐ferritin (CD68+/H‐ferritin+ or double‐positive cells for CD68 and L‐ferritin (CD68+/L‐ferritin+) and clinical features, Spearman's correlation analysis and linear regression were used. The same analysis was performed to evaluate a possible correlation among H‐ferritin and IL‐1β, TNF and IFN‐γ. A P‐value < 0·05 expressed a statistically significant result. We used GraphPad Prism version 5.0 for all statistical analyses.

Results

Demographic and clinical features

In this study, we evaluated BM biopsies of 10 patients affected by MAS collected during the full‐blown syndrome. All these adult patients were affected by proinflammatory rheumatic disease (eight patients by AOSD, two patients by SLE), and MAS occurred during disease flare or severe infection. We observed that two patients experienced MAS after severe Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection and two patients during Gram‐negative sepsis, due to immunosuppressive treatments administered for underlying rheumatic disease. All these patients showed peripheral blood cytopenia [WBC, mean ± standard deviation (s.d.) 3·23 ± 1·44, 103/ml; RBC = 3·22 ± 0·70, 103/ml; PLT = 45·52 ± 26·60, 103/ml], increased serum levels of ferritin (2842·70 ± 569·70 ng/ml), marked increase of inflammatory markers (ESR = 63·87 ± 30·19, mm/h; CRP = 51·59 ± 46·92, mg/day). The clinical data are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical features of evaluated macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) patients

| Clinical data | Patients |

|---|---|

| Women (men) | 4 (6) |

| Age (years ± s.d.) | 58·20 ± 13·10 |

| Underlying disease, number (%) | 10 (100%) |

| AOSD | 8 (80%) |

| SLE | 2 (20%) |

| Trigger factor, number (%) | |

| Flare of the disease | 6 (60%) |

| Severe infection | 4 (40%) |

| Comorbidities, number (%) | 4 (40%) |

| Time of follow‐up, months mean ± s.d. | 6·96 ± 2·82 |

| MAS‐related death, number (%) | 5 (50%) |

| Laboratory parameters | |

| WBC (103/ml), mean ± s.d. | 3·23 ± 1·44 |

| RBC (103/ml), mean ± s.d. | 3·22 ± 0·70 |

| HB (g/dl), mean ± s.d. | 8·79 ± 1·55 |

| PLT (103/ml), mean ± s.d. | 45·52 ± 26·60 |

| Serum ferritin (ng/ml), mean ± s.d. | 2842·70 ± 569·70 |

| ESR (mm/h), mean ± s.d. | 63·87 ± 30·19 |

| CRP (mg/l), mean ± s.d. | 51·59 ± 46·92 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl), mean ± s.d. | 220·02 ± 71·25 |

| ASAT (IU/l), mean ± s.d. | 84·23 ± 51·97 |

| ALAT (IU/l), mean ± s.d. | 145·28 ± 94·23 |

| Therapies | |

| High‐dosage steroids pulses, number (%) | 10 (100%) |

| Methylprednisolone pulses 1000 mg/die | 7 (70%) |

| Methylprednisolone pulses 500 mg/die | 3 (30%) |

| Immunosuppressive drugs, number (%) | 5 (50%) |

| Cyclosporin A | 5 (50%) |

ALAT = alanine aminotransferase; AOSD = adult‐onset Still's disease; ASAT = aspartate aminotransferase; CRP = C‐reactive protein; ESR = serum ferritin, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HB = haemoglobin; MAS = macrophage activation syndrome; PLT = platelet count; RBC = red blood cells; SLE = systemic lupus erythematosus; WBC = white blood cell count.

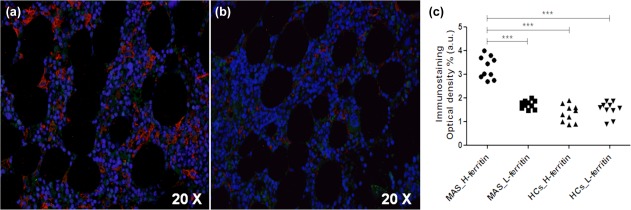

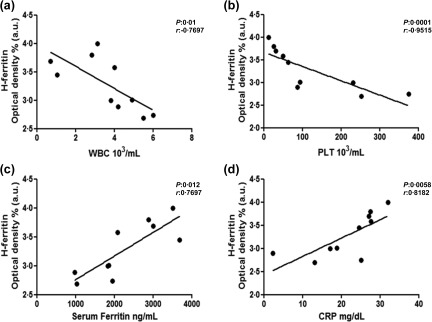

H‐ferritin is increased in BM and correlates with clinical features

We observed a granular morphological pattern of H‐ferritin and L‐ferritin immunoreactivity, including cytoplasmatic and extracellular localization, using immunofluorescence. As shown in Fig. 1, H‐ferritin was increased in BM samples of MAS patients when compared with both L‐ferritin and HCs (P < 0·0001 for each comparison), analysing the optical density of immunofluorescence. Conversely, L‐ferritin was not increased when compared to HCs. Subsequently, clinical correlations among these histological data and severity of the clinical picture were evaluated. Our analyses showed that the peripheral blood cytopenia of these patients were correlated inversely with the levels of H‐ferritin in the BM of MAS. Increased values of H‐ferritin levels correlated with decreased WBC and PLT counts (P = 0·01, P = 0·0001; respectively). A further correlation was observed among tissue H‐ferritin and the inflammatory markers. H‐ferritin was correlated statistically with both serum ferritin and CRP levels (P = 0·012; P = 0·0058, respectively), as shown in Fig. 2. No correlation was observed among RBC count, levels of HB, ESR, ASAT, ALAT and H‐ferritin. The correlations among L‐ferritin and clinical data did not show significant results.

Figure 1.

Expression of H‐ferritin in bone marrow samples of macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) patients. (a) high H‐ferritin (red) and low tissue expression of L‐ferritin (green) may be observed, respectively; (b) low H‐ferritin expression may be reported in healthy controls (HCs); (c) H‐ferritin was increased significantly when compared with L‐ferritin increased and HCs, analysing immunostaining optical density (***P < 0·0001).

Figure 2.

Correlation of H‐ferritin with clinical features. (a,b) Increased values of H‐ferritin were correlated with decreased white blood cells (WBC) and platelet (PLT) counts, respectively; (c) significantly and (d) increased values of H‐ferritin tissue were correlated significantly with increased values of serum ferritin and C‐reactive protein (CRP), respectively.

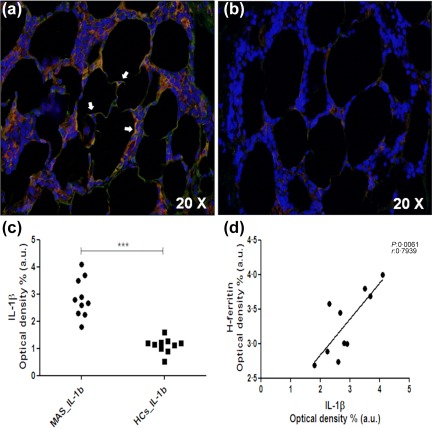

IL‐1β, TNF, IFN‐γ and H‐ferritin

Proinflammatory cytokines were increased significantly in BM samples of MAS patients when compared with HCs analysing the immunofluorescence of our samples. Specifically, a marked increase of IL‐1β was observed in BM of MAS patients (P = 0·0002). In addition, the analyses showed a significant correlation between the tissue expression of H‐ferritin and IL‐1β (P = 0·006). Interestingly, H‐ferritin and IL‐1β co‐localized in the BM samples of our patients, as shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3.

Expression interleukin (IL)‐1β in bone marrow of macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) patients and its correlation with H‐ferritin. (a) Increased IL‐1β (green) levels and co‐localization (arrows) between H‐ferritin (red), and this cytokine may be observed in the inflammatory bone marrow infiltrate; (b) reduced IL‐1β expression in healthy controls (HCs); (c) in MAS patients, IL‐1β was increased significantly when compared with HCs (***P < 0·001); (d) IL‐1β was correlated significantly with H‐ferritin.

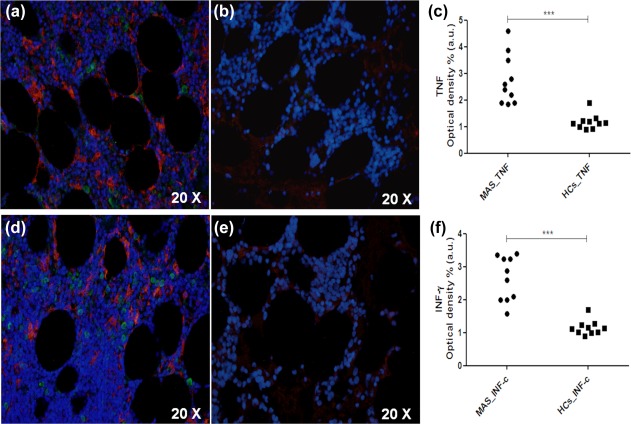

Furthermore, we showed a significant increase of TNF in the BM of evaluated patients when compared with HCs (P = 0·002) (Fig. 4). Similarly, a marked increase of IFN‐γ was observed when compared with HCs (P < 0·0001). However, we did not report correlation or co‐localization among these proinflammatory cytokines and H‐ferritin.

Figure 4.

Increased expression of tumour necrosis factor (TNF) and interferon (IFN)‐γ in bone marrow of macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) patients. (a) Increased IFN‐γ (green) levels and H‐ferritin (red) may be described in MAS; (b) reduced IFN‐γ levels in healthy controls (HCs); (c) IFN‐γ was increased significantly when MAS patients were compared with HCs (***P < 0·001); (d) increased TNF (green) levels and H‐ferritin (red) may be observed in MAS; (e) reduced TNF levels in HCs; (f) TNF was increased significantly when MAS patients were compared with HCs (***P < 0·001).

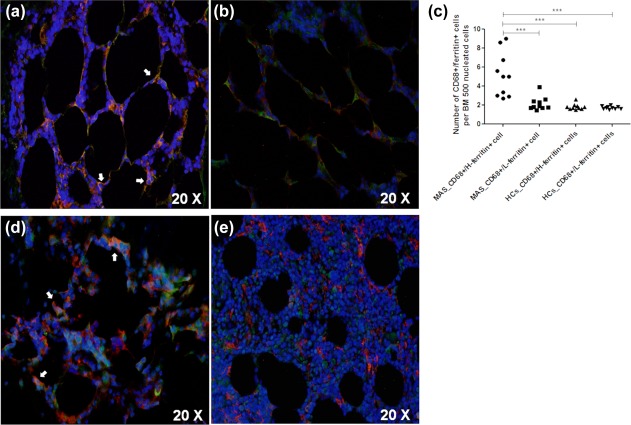

CD68+/H‐ferritin+ macrophages are increased and correlate with clinical features

In our MAS patients, we reported that H‐ferritin co‐localized with CD68, as shown in Fig. 5. Furthermore, macrophages expressing H‐ferritin in the inflammatory infiltrate were increased significantly when compared with HCs (P = 0·006) (Fig. 5). In the same samples, although we observed a weak co‐localization between CD68 and L‐ferritin, these cells did not differ significantly when compared with HCs. We analysed and compared the number of CD68+/H‐ferritin+ cells with the number of CD68‐/H‐ferritin+ cells, pointing out that a large percentage of H‐ferritin+ cells expressed CD68 (CD68+/H‐ferritin+ cells: 5 median, range = 2·7; 9·0 versus CD68‐/H‐ferritin+ cells 1·7 median, range = 1·5; 2·2; P < 0·0001). In addition, we analysed possible co‐localizations among the H‐ferritin and IL‐12, which is considered an M1 macrophage marker, and CD163, which is considered an M2 macrophage marker, as shown previously 19, 20. As shown in Fig. 5, a co‐localization between H‐ferritin and IL‐12 was observed. Conversely, a weaker co‐expression between H‐ferritin and CD163 was shown. We analysed and compared the number of IL‐12+/H‐ferritin+ cells with the number of CD163/H‐ferritin+ cells, indicating that a large percentage of H‐ferritin+ cells expressed IL‐12 (IL‐12+/H‐ferritin+ cells: 3·2 median, range = 1·6; 6·1) versus CD163+/H‐ferritin+ cells 1·6 median, range = 1·3; 2·7; P = 0·0002) and suggesting an increased percentage of M1 macrophages in BM inflammatory infiltrate during MAS full‐blown syndrome.

Figure 5.

CD68 macrophages expressing H‐ferritin in bone marrow infiltrate of macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) patients. (a) CD68+/H‐ferritin+ cells (arrows) may be described in the bone marrow (BM) of MAS patients; (b) reduced CD68+/H‐ferritin+ cells in BM of healthy controls (HCs); (c) CD68+/H‐ferritin+ cells was increased significantly in MAS when compared with HCs (***P < 0·001); (d) co‐localization of H‐ferritin (red) and interleukin (IL)‐12 (green) may be observed, suggesting M1 macrophages; (e) CD163+ cells (green) showed weaker co‐localization with H‐ferritin (red).

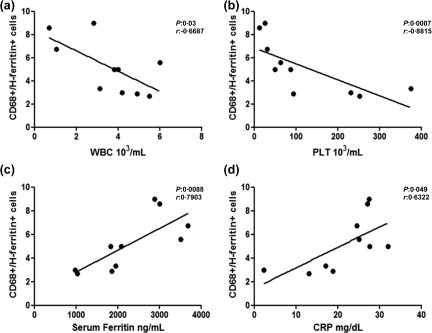

In addition, clinical correlations among CD68+/ferritin+ cells and severity of the clinical picture were assessed. Our analyses showed that the peripheral blood cytopenia of these patients were correlated inversely with the number of BM CD68+/H‐ferritin+ cells in the inflammatory BM infiltrate. Increased values of CD68+/H‐ferritin+ cells in the BM inflammatory infiltrate of our patients correlated with reduced WBC and the PLT counts (P = 0·03, P = 0·0007, respectively). Furthermore, CD68+/H‐ferritin+ cells were correlated significantly with both serum ferritin and CRP levels (P = 0·0088; P = 0·049; respectively). Figure 6 shows these statistical analyses. ESR, RBC count and HB levels did not correlate with CD68+/H‐ferritin+ cells. pCD68+/L‐ferritin+ cells in the BM inflammatory infiltrate of MAS patients did not correlate with these clinical parameters.

Figure 6.

Correlation between CD68+/H‐ferritin+ cells, haematological involvement and inflammatory markers. (a,b) Increased CD68+/H‐ferritin+ was correlated with decreased white blood cell (WBC) and decreased platelet (PLT) counts, respectively; (c,d) CD68+/H‐ferritin+ was correlated significantly with serum ferritin and C‐reactive protein (CRP).

Discussion

In our study, H‐ferritin, CD68+/H‐ferritin+ cells and proinflammatory cytokines, IL‐1β, TNF, IFN‐γ, were increased markedly in BM inflammatory infiltrate of MAS patients. Of note, H‐ferritin and CD68+/H‐ferritin+ cells were correlated significantly with the haematological involvement of our patients, suggesting possible biomarkers of severity.

During MAS, the massive release/production of proinflammatory cytokines may induce H‐ferritin expression by activation of specific transcription factors, such as ferritin 2 (FER2), which may in turn activate production of further proinflammatory cytokines, triggering a possible vicious loop 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26. In fact, we observed high H‐ferritin in the BM of MAS patients and co‐localization as well as a correlation between H‐ferritin and IL‐1β, a possibly therapeutic target in MAS and rheumatic diseases 27, 28, 29, 30, 31. Furthermore, a specific receptor for H‐ferritin on immune cells has also been reported 32. The specific binding between H‐ferritin and the T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain‐containing protein‐2 (TIM‐2) receptor may modulate the inflammatory process. This is a member of the TIM gene family and is expressed by T helper type 2 (Th2) cells and macrophages in the context of the proinflammatory milieu 32, 33. The binding H‐ferritin/TIM‐2 may activate these immune cells, leading to subsequent pathogenic proinflammatory process 12, 18, 19, 20, 21. Taking together all these mechanisms, it is possible to speculate that the enhanced tissue expression of H‐ferritin, via a vicious loop, may perpetuate the production of proinflammatory cytokines, possible therapeutic targets in MAS 16, 17, 22, 23, 27, 28.

In our samples, we described macrophages co‐expressing CD68 and H‐ferritin that were increased in the BM infiltrate of MAS. These data may confirm that, after proinflammatory stimuli, macrophages may release H‐ferritin, confirming their role in ferritin production 34. Interestingly, H‐ferritin co‐localized with IL‐12, a marker of M1‐macrophages, associated with increased production of proinflammatory molecules. Macrophages are polarized by environment, mainly the cytokine milieu, towards distinct functional programmes, categorized as M1 and M2 pathways. Massive production of IL‐1β, INF‐γ and TNF may promote the recruitment and proliferation of M1 macrophages; persistent and uncontrolled expansion of these proinflammatory macrophages is a pivotal mechanism in MAS development 35, 36.

To date, H‐ferritin and CD68+/H‐ferritin+ cells were correlated significantly with haematological involvement, serum ferritin and CRP of our MAS patients. These results suggest potentially new biomarkers evaluating severity of the MAS clinical picture, possibly improving outcome in these patients 37, 38. In fact, diagnosis and appropriate treatments may be delayed, due to non‐specific findings in the early phases of disease, thus new biomarkers may improve the management of this life‐threating syndrome 39, 40, 41, 42. Although a rigorous process of validation is needed, the use of novel biomarkers in these patients may help physicians, thus improving diagnosis with early recognition and prompt therapy as well as predicting response to treatment and outcome, as suggested in other rheumatic diseases 43, 44, 45, 46, 47.

Our retrospective study shows different limitations. We evaluated a low number of patients, thus our findings should be confirmed further. However, it must be pointed out that MAS is a very rare disease and, as observed for other infrequent complications during rheumatic diseases, organizing specifically designed studies may be a challenge 48, 49, 50. Furthermore, our study did not allow us to indicate if the CD68+ macrophages are actively producing ferritin or phagocyting cells and future specifically designed studies are needed to elucidate these pathogenic steps entirely during MAS.

In conclusion, H‐ferritin, CD68+/H‐ferritin+ cells IL‐1β, TNF, IFN‐γ, were increased markedly in BM inflammatory infiltrate of MAS patients, possibly involved in a proinflammatory pathogenic vicious loop. Although future studies are needed to clarify entirely the possible role of these features, our results may allow us to hypothesize that ferritin and CD68+/H‐ferritin+ macrophages may not only be considered a consequence of the inflammation but are involved directly in MAS pathogenesis. Furthermore, H‐ferritin and CD68+/H‐ferritin+ cells are correlated significantly with haematological involvement of our patients, suggesting possible biomarkers of severity in order to improve the management of patients, allowing physicians an early recognition and prompt therapy for this life‐threating syndrome.

Disclosure

The authors declare there are no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mrs Federica Sensini for her technical assistance. This study received no support in the form of grants or industrial support.

References

- 1. Ramos‐Casals M, Brito‐Zerón P, López‐Guillermo A, Khamashta MA, Bosch X. Adult haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet 2014; 383:1503–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Grom AA, Horne A, De Benedetti F. Macrophage activation syndrome in the era of biologic therapy. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2016; 12:259–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ruscitti P, Cipriani P, Masedu F et al Adult‐onset Still's disease: evaluation of prognostic tools and validation of the systemic score by analysis of 100 cases from three centers. BMC Med 2016; 14:194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Minoia F, Davì S, Horne A et al Dissecting the heterogeneity of macrophage activation syndrome complicating systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol 2015; 42:994–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Efthimiou P, Kadavath S, Mehta B. Life‐threatening complications of adult‐onset Still's disease. Clin Rheumatol 2014; 33:305–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sfriso P, Priori R, Valesini G et al Adult‐onset Still's disease: an Italian multicentre retrospective observational study of manifestations and treatments in 245 patients. Clin Rheumatol 2016; 35:1683–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cipriani P, Ruscitti P, Carubbi F et al Tocilizumab for the treatment of adult‐onset Still's disease: results from a case series. Clin Rheumatol 2014; 33:49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ruscitti P, Cipriani P, Ciccia F et al Prognostic factors of macrophage activation syndrome, at the time of diagnosis, in adult patients affected by autoimmune disease: analysis of 41 cases collected in 2 rheumatologic centers. Autoimmun Rev 2017; 16:16–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ahn SS, Yoo BW, Jung SM et al Application of the 2016 EULAR/ACR/PRINTO classification criteria for macrophage activation syndrome in patients with adult‐onset Still disease. J Rheumatol 2017; 44:996–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Arca M, Fardet L, Galicier L et al Prognostic factors of early death in a cohort of 162 adult haemophagocytic syndrome: impact of triggering disease and early treatment with etoposide. Br J Haematol 2015; 168:63–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cipriani P, Ruscitti P, Carubbi F, Liakouli V, Giacomelli R. Methotrexate: an old new drug in autoimmune disease. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2014; 10:1519–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Giacomelli R, Afeltra A, Alunno A et al International consensus: what else can we do to improve diagnosis and therapeutic strategies in patients affected by autoimmune rheumatic diseases (rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthritides, systemic sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, antiphospholipid syndrome and Sjogren's syndrome)? The unmet needs and the clinical grey zone in autoimmune disease management. Autoimmun Rev 2017; 16:911–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bracaglia C, Prencipe G, De Benedetti F. Macrophage activation syndrome: different mechanisms leading to a one clinical syndrome. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 2017; 15:5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Strippoli R, Caiello I, De Benedetti F. Reaching the threshold: a multilayer pathogenesis of macrophage activation syndrome. J Rheumatol 2013; 40:761–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mills CD. M1 and M2 macrophages: oracles of health and disease. Crit Rev Immunol 2012; 32:463–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ruscitti P, Cipriani P, Di Benedetto P et al Increased level of H‐ferritin and its imbalance with L‐ferritin, in bone marrow and liver of patients with adult onset Still's disease, developing macrophage activation syndrome, correlate with the severity of the disease. Autoimmun Rev 2015; 14:429–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rosário C, Zandman‐Goddard G, Meyron‐Holtz EG, D'Cruz DP, Shoenfeld Y. The hyperferritinemic syndrome: macrophage activation syndrome, Still's disease, septic shock and catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome. BMC Med 2013; 11:185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M et al Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2007; 48:124–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chong BF, Tseng LC, Hosler GA et al A subset of CD163+ macrophages displays mixed polarizations in discoid lupus skin. Arthritis Res Ther 2015; 17:324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhang W, He KF, Yang JG et al Infiltration of M2‐polarized macrophages in infected lymphatic malformations: possible role in disease progression. Br J Dermatol 2016; 175:102–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Torti FM, Torti SV. Regulation of ferritin genes and protein. Blood 2002; 99:3505–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Recalcati S, Invernizzi P, Arosio P, Cairo G. New functions for an iron storage protein: the role of ferritin in immunity and autoimmunity. J Autoimmun 2008; 30:84–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ruddell RG, Hoang‐Le D, Barwood JM et al Ferritin functions as a proinflammatory cytokine via iron‐independent protein kinase C zeta/nuclear factor kappaB‐regulated signaling in rat hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology 2009; 49:887–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wei Y, Miller SC, Tsuji Y, Torti SV, Torti FM. Interleukin 1 induces ferritin heavy chain in human muscle cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1990; 169:289–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Piñero DJ, Hu J, Cook BM, Scaduto RC Jr, Connor JR. Interleukin‐1beta increases binding of the iron regulatory protein and the synthesis of ferritin by increasing the labile iron pool. Biochim Biophys Acta 2000; 1497:279–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ben‐Neriah Y, Karin M. Inflammation meets cancer, with NF‐κB as the matchmaker. Nat Immunol 2011; 12:715–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vitale A, Insalaco A, Sfriso P et al A Snapshot on the on‐label and off‐label use of the interleukin‐1 inhibitors in Italy among rheumatologists and pediatric rheumatologists: a nationwide multi‐center retrospective observational study. Front Pharmacol 2016; 7:380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lopalco G, Cantarini L, Vitale A et al Interleukin‐1 as a common denominator from autoinflammatory to autoimmune disorders: premises, perils, and perspectives. Mediators Inflamm 2015; 2015:194864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Colafrancesco S, Priori R, Valesini G et al Response to Interleukin‐1 inhibitors in 140 Italian patients with adult‐onset Still's disease: a multicentre retrospective observational study. Front Pharmacol 2017; 8:369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ruscitti P, Cipriani P, Carubbi F et al The role of IL‐1β in the bone loss during rheumatic diseases. Mediators Inflamm 2015; 2015:782382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Giacomelli R, Ruscitti P, Alvaro S et al IL‐1β at the crossroad between rheumatoid arthritis and type 2 diabetes: may we kill two birds with one stone? Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2016; 12:849–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rodriguez‐Manzanet R, DeKruyff R, Kuchroo VK, Umetsu DT. The costimulatory role of TIM molecules. Immunol Rev 2009; 229:259–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chen TT, Li L, Chung DH et al TIM‐2 is expressed on B cells and in liver and kidney and is a receptor for H‐ferritin endocytosis. J Exp Med 2005; 202:955–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cohen LA, Gutierrez L, Weiss A et al Serum ferritin is derived primarily from macrophages through a nonclassical secretory pathway. Blood 2010; 116:1574–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Colafrancesco S, Priori R, Alessandri C et al sCD163 in AOSD: a biomarker for macrophage activation related to hyperferritinemia. Immunol Res 2014; 60:177–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Priori R, Colafrancesco S, Alessandri C et al Interleukin 18: a biomarker for differential diagnosis between adult‐onset Still's disease and sepsis. J Rheumatol 2014; 41:1118–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ruscitti P, Ciccia F, Cipriani P et al The CD68(+)/H‐ferritin(+) cells colonize the lymph nodes of the patients with adult onset Still's disease and are associated with increased extracellular level of H‐ferritin in the same tissue: correlation with disease severity and implication for pathogenesis. Clin Exp Immunol 2016; 183:397–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ruscitti P, Cipriani P, Ciccia F et al H‐ferritin and CD68(+)/H‐ferritin(+) monocytes/macrophages are increased in the skin of adult‐onset Still's disease patients and correlate with the multi‐visceral involvement of the disease. Clin Exp Immunol 2016; 186:30–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sen ES, Steward CG, Ramanan AV. Diagnosing haemophagocytic syndrome. Arch Dis Child 2017; 102:279–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gohar F, Kessel C, Lavric M, Holzinger D, Foell D. Review of biomarkers in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: helpful tools or just playing tricks? Arthritis Res Ther 2016; 18:163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ruscitti P, Rago C, Breda L et al Macrophage activation syndrome in Still's disease: analysis of clinical characteristics and survival in paediatric and adult patients. Clin Rheumatol 2017. doi: 10.1007/s10067-017-3830-3. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bracaglia C, de Graaf K, Pires Marafon D et al Elevated circulating levels of interferon‐γ and interferon‐γ‐induced chemokines characterise patients with macrophage activation syndrome complicating systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017; 76:166–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ruscitti P, Cipriani P, Di Benedetto P et al Advances in immunopathogenesis of macrophage activation syndrome during rheumatic inflammatory diseases: toward new therapeutic targets? Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2017. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2017.1372194. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Koutsonikoli A, Trachana M, Farmaki E et al Novel biomarkers for the assessment of paediatric systemic lupus erythematosus nephritis. Clin Exp Immunol 2017; 188:79–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kostik MM, Dubko MF, Masalova VV et al Identification of the best cutoff points and clinical signs specific for early recognition of macrophage activation syndrome in active systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2015; 44:417–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ursini F, Grembiale A, Naty S, Grembiale RD. Serum complement C3 correlates with insulin resistance in never treated psoriatic arthritis patients. Clin Rheumatol 2014; 33:1759–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Aggarwal A, Gupta R, Negi VS et al Urinary haptoglobin, alpha‐1 anti‐chymotrypsin and retinol binding protein identified by proteomics as potential biomarkers for lupus nephritis. Clin Exp Immunol 2017; 188:254–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ruscitti P, Ursini F, Cipriani P, De Sarro G, Giacomelli R. Biologic drugs in adult onset Still's disease: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of observational studies. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2017; 1–9. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2017.1375853. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ursini F, Naty S, Mazzei V et al Retrospective analysis of type 2 diabetes prevalence in a systemic sclerosis cohort from southern Italy: comment on ‘Reduced incidence of Type 1 diabetes and Type 2 diabetes in systemic sclerosis: a nationwide cohort study’ by Tseng et al. Joint Bone Spine 2016; 83:307–13. Joint Bone Spine 2016; 83:611–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ursini F, Naty S, Mazzei V, Spagnolo F, Grembiale RD. Kaposi's sarcoma in a psoriatic arthritis patient treated with infliximab. Int Immunopharmacol 2010; 10:827–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]